By the Numbers: Income and Poverty, 2020

Jump to statistics on:

• Earnings

• Incomes

• Poverty

• Policy / SPM

This fact sheet provides key numbers from today’s new Census reports, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2020 and The Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2020. Each section has headline statistics from the reports for 2020, as well as comparisons with the previous year. This fact sheet also provides historical context for the 2020 recession by analyzing changes between the last business cycle peak in 2019 to 2007 (the final year of the economic expansion that preceded the Great Recession), and to 2000 (the prior economic peak). All dollar values are adjusted for inflation (2020 dollars). Because of a redesign in the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC) income questions in 2013, we imputed the historical series using the ratio of the old and new method in 2013. All percentage changes from before 2013 are based on this imputed series. We do not adjust for the break in the series in 2017 due to differences in the legacy CPS ASEC processing system and the updated CPS ASEC processing system, but these differences are small and statistically insignificant in most cases.

The 2020 Census report highlights the costs of the pandemic and benefits of early policy safety net measures

This morning, the Census Bureau released its report on income, poverty, and health insurance for 2020. These data provide insights into the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on earnings and incomes as well as the vital measures put in place to reduce economic insecurity during the steep economic downturn.

Median household income fell 2.9% as millions lost their jobs and poverty rose by 1.0 percentage point. The losses to income and increases in poverty would have been far worse if not for the rapid and large boosts to vital safety net programs legislated by Congress in 2020. The stimulus payments moved 11.7 million people out of poverty and unemployment insurance—expanded in 2020—lifted 5.5 million out of poverty in 2020.

Overall, median earnings for full-time workers rose 6.9% largely in response to a composition shift in who was more able to retain employment (and who did not). Since a disproportionate share of workers who lost their jobs were lower paid, the remaining workers in the economy are higher paid, on average, leading to a mechanical increase in earnings. This does not reflect an increase in living standards for those working, rather it’s just a quirk of arithmetic.

Here are some key takeaways from the 2020 report.

Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey reflects labor market before August’s Delta variant surge

Below, EPI senior economist Elise Gould offers her initial insights on today’s release of the Jobs and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) for July. Read the full Twitter thread here.

Hires ticked down slightly in July but remains up 645k since May. Total separations rose for two months running due to an increase in both layoffs and quits. Quits are high by historical standards as workers may be concerned about rising covid cases or are finding better jobs. pic.twitter.com/H1likO3kS6

— Elise Gould (@eliselgould) September 8, 2021

Using the last three months of data by sector to smooth data volatility, it’s clear that there are still many sectors with more unemployed workers than job openings. To be clear, these comparisons only include those who are in the official measure of unemployment. pic.twitter.com/r6C1aR3NX1

— Elise Gould (@eliselgould) September 8, 2021

#JOLTS provides a different picture of the labor market, with its data on job openings, hires, quits, and layoffs, but it is decidedly a bit out of date as fast changing as the recovery and pandemic has been the last year and a half. https://t.co/zBNnd11mGR

— Elise Gould (@eliselgould) September 8, 2021

Disappointing job growth in August as the Delta variant surged

Below, EPI economists offer their initial insights on the August jobs report released this morning, which showed an increase of 235,000 jobs—a notable slowdown from June and July.

Growing inequalities, reflecting growing employer power, have generated a productivity–pay gap since 1979: Productivity has grown 3.5 times as much as pay for the typical worker

Key takeaways:

- Productivity and pay once climbed together. But in recent decades, productivity and pay have diverged: Net productivity grew 59.7% from 1979-2019 while a typical worker’s compensation grew by 15.8%, according to EPI data released ahead of Labor Day.

- If median hourly compensation had grown at the same rate as productivity over the 1979-2019 period, the median worker would be making $9.00 more per hour.

- This divergence has been primarily driven by intentional policy choices creating rising inequality: both the top 10% and especially the top 1% and top 0.1% gained a much larger share of all compensation and labor’s share of income eroded.

- Public policies which restore worker power and balance in the labor market can provide robust, widely shared wage growth.

The growth of inequalities is the central driver of the widening gap between the hourly compensation of a typical (median) worker and productivity—the income generated per hour of work—in recent decades. Specifically, this growing divergence has been driven by the growth of two distinct dimensions of inequality: the surge of compensation received by the top 10%—particularly the top 1.0% and top 0.1%—and the erosion of labor’s share of income and the corresponding growth of capital’s share. This post documents these trends by presenting an updated account of the U.S. productivity-pay divergence originally analyzed in both Mishel and Gee 2012 and Bivens and Mishel 2015.

The key metric, as explained below, is the lag between the growth of net productivity (taking into account depreciation and evaluated using consumer prices) and hourly compensation (wages and benefits) of a typical or median worker. Between 1979 and 2019, net productivity grew 59.7% while a typical (median) worker’s compensation grew by 15.8%, a 43.9 percentage point divergence driven by inequality. The effects have been felt broadly: During this period, 90% of U.S. workers experienced wage growth (26%) far slower than the economywide average, while workers in the top 1% (mostly highly credentialed professionals and corporate managers) saw 160% wage growth (Mishel and Kandra 2020) and owners of capital reaped large rewards made possible only by this anemic wage growth for the bottom 90%.

What to watch on jobs day: Labor market growth may slow as the Delta variant surged in August

While the official pandemic recession ended two months after it began, it is clear that the pandemic is not behind us and its ebbs and flows exert powerful effects on economic growth. The seven-day moving average of U.S. COVID-19 cases rose more than fivefold, from 24,000 per day to 126,000 per day between July 12 and August 12, 2021, roughly representing the reference period for each month’s labor market report. The economic effects of this surge will likely be reflected in the jobs numbers we receive on Friday as segments of the U.S. workforce still face health and safety risks of continuing to work in person. This emphasizes the importance of continuing to provide a safety net for workers and their families—including by keeping in place federal pandemic unemployment insurance (UI) benefits—as health and safety-related closures and protective measures are reinstated.

While the job growth numbers in June and July (938,000 and 943,000, respectively) provided strong evidence that the labor market is revving back up in response to fiscal stimulus and widespread vaccinations, it is likely that the August job growth numbers may be more muted. The fivefold increase in COVID-19 cases is likely one of the reasons that restaurant seating appears to have softened between July and August.

Bargaining over COVID-19 vaccine requirements doesn’t mean unions oppose mandates: EPI’s Dave Kamper provides a Twitter reality check

Unions across the country are working on doing what’s right for society and their members when it comes to COVID-19 vaccine mandates. But there has been some misplaced criticism directed toward unions, especially public-sector unions who engage in “impact bargaining” with their employer over COVID-19 vaccine mandates.

To put it all in perspective, Dave Kamper, senior state policy coordinator for the Economic Analysis and Research Network (EARN) at the Economic Policy Institute, took to social media to break down the mandate issue and also to explain how impact bargaining isn’t about refusing to follow mandates, but about how changes are implemented and how they impact working conditions.

A century after the Battle of Blair Mountain, protecting workers’ right to organize has never been more important

Thousands are expected this week in the forested hills of southern West Virginia to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Blair Mountain—a key conflict in labor history.

In the late summer of 1921, at least 7,000 coal miners affiliated with the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) fought for their rights and their livelihoods in a weeklong fight against a private army that was raised by the coal companies and supported by the National Guard and the U.S. Army Air Force. The battle was the climax of two decades of low-intensity warfare across the coalfields of Appalachia, and it remains the largest battle on U.S. soil since the end of the Civil War.

The battle is also a stark reminder of the importance of protecting workers’ right to organize. It’s not simply about balancing the economic scales; it’s about power. When workers do not have power—when they have no voice in their workplace and no voice in how the nation is governed—exploitation and violence by the state are the inevitable result.

Today, workers still face a lack of power. A great way to empower workers would be through passing the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, which is currently being considered by Congress and was renamed after former UMWA President Richard Trumka following his passing earlier this month. The story of the Battle of Blair Mountain demonstrates how, a hundred years on, workers are at the mercy of the powerful unless they have unions and power of their own.

Cutting unemployment insurance benefits did not boost job growth: July state jobs data show a widespread recovery

Key takeaways:

- The July state employment and unemployment data released Friday showed that strong job growth is widespread throughout the country, including in leisure and hospitality and state and local governments.

- States that chose not to cut federal pandemic unemployment insurance (UI) benefits have, on average, experienced greater job growth since April than the 26 largely Republican-controlled states that cut benefits to unemployed workers.

- Leisure and hospitality employment has grown at a quicker rate in states that preserved full UI benefits than in those that cut federal assistance.

- However, with a nationwide jobs shortfall of between 6.6 and 9.1 million jobs, the economic recovery is still far from complete. Policymakers at every level of government should take action to help speed the recovery.

The July state employment and unemployment data released Friday by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) showed that the strong job growth reported earlier this month in the national jobs data was widespread throughout the country. And, notably, the states that chose not to cut pandemic unemployment insurance (UI) benefits have experienced, on average, greater job growth in recent months than states that cut benefits to unemployed workers.

Over the last three months (from April to July), all but three states—Alaska, Kentucky, and Wyoming—added jobs, with particularly strong growth in Hawaii (4.0%), Vermont (3.5%), North Carolina (2.7%), Arizona (2.6%), and New Mexico (2.5%). Figure A shows each state’s July unemployment rate and the change in employment over the past three months, 12 months, and since February 2020 (the month before the recession.)

Richard Trumka was a champion for workers’ rights: Passing the PRO Act was one of his top priorities

The labor movement lost a giant last week. Richard Trumka was a champion for workers’ rights and a passionate leader of the labor movement. In addition to serving as President of the AFL-CIO, Trumka served as Chairman of EPI’s board of directors since 2012. Under President Trumka’s leadership, EPI and AFL-CIO have shared an unwavering commitment to advancing workers’ rights and strengthening unions.

For President Trumka, “the next frontier” for U.S. workers was the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act. Passing the PRO Act would restore workers’ ability to organize with their co-workers and would allow them to negotiate for better pay, benefits, and fairness on the job. Passing the PRO Act would also promote greater racial economic justice because unions and collective bargaining help shrink the Black–white wage gap.

Every day, corporations openly bust unions and retaliate against working people without consequence. President Trumka spent his career fighting these attacks on working people’s right to organize and collectively bargain. We need meaningful policy changes to restore a fair balance of power between workers and employers. That is why Congress must pass the PRO Act.

As President Trumka said on June 29, “the single best agent for change is the PRO Act.” We at EPI will honor his memory by continuing to advance policies like the PRO Act that are critical to workers and a fair economy.

July inflation data show the lowest monthly gain in consumer prices since February

Below, EPI director of research Josh Bivens offers his initial insights on today’s release of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for July. The data show the lowest monthly gain in consumer prices (0.5%) since February and ultimately support a transitory view of inflation. Read the full Twitter thread here.

The core index (excluding food and energy) saw an even much larger deceleration – rising 0.3% in July from 0.9% growth the month before. The big story in the data is that the used car price spike finally flattened out. 2

— Josh Bivens (@joshbivens_DC) August 11, 2021

June Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey shows an uptick in hires and quits, while layoffs dropped

Below, EPI senior economist Elise Gould offers her initial insights on today’s release of the Jobs and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) for June. Read the full Twitter thread here.

The uptick in the quits rate is notable, likely due in part to increased opportunities for workers to find better job matches, potentially with higher wages or safer working conditions in the lingering pandemic (which had not worsening as much during the June reference period). pic.twitter.com/bYOCIhlEYy

— Elise Gould (@eliselgould) August 9, 2021

The racist campaign against ‘critical race theory’ threatens democracy and economic transformation

Over the past several months, conservative lawmakers and activists have carried out a concerted assault against a wide range of efforts and ideas that raise awareness about the history of racial injustice in the United States, its embeddedness in our society, and the resulting inequities observed today. Attackers have grouped and conflated all these concepts and ideas into what they are dubbing “critical race theory.” But those carrying out this campaign are not interested in what the actual academic critical race theory (CRT) says.

In fact, what is actually under attack is the reinvigorated movement across the United States to engage in dialogue about our country’s continuing legacy of racial hierarchy and oppression—and the policy choices that could finally begin to redress that legacy. And while the campaign against critical race theory is recent, it is merely the latest tool many states have wielded in order to disempower and further disenfranchise Black people as well as cut off any broad-based support for structural reform.

July jobs report shows an economy on track to recover five times as fast as the Great Recession recovery

Below, EPI economists offer their initial insights on the July jobs report released today, which showed an increase in 943,000 jobs. They see strong growth in employment, including in leisure and hospitality, and an economic recovery on track to pre-COVID health by the end of 2022.

From EPI senior economist, Elise Gould (@eliselgould):

Read the full twitter thread here.

After ticking up in June, the unemployment rate fell for the right reasons in July as more people found work rather than left the labor force.

The unemployment rate fell for all race/ethnic groups in July, but the unemployment rate for Black male workers remains high at 8.4%. pic.twitter.com/CONN2kcadk

— Elise Gould (@eliselgould) August 6, 2021

State and local American Rescue Plan funds should be used to support an equitable recovery for workers

Last month, we at the Economic Policy Institute submitted a public comment on the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s guidance regarding the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds. These funds are part of the American Rescue Plan (ARP) Act’s resources for state and local communities to respond to the public health and economic crisis. The funds—nearly $350 billion—may be used to support public health responses, mitigate negative economic impacts, replace public-sector revenue lost due to the pandemic, provide premium pay for “essential” workers, and make necessary investments in water, sewer, and broadband infrastructure.

The current public health and economic crisis is happening in the wake of more than a decade of underinvestment by state and local governments. During the Great Recession, cuts to jobs and state and local spending delayed a full recovery to pre-recession unemployment rates by more than four years. Public-sector job losses, especially in state and local education, were among the highest during the pandemic. Cuts to public services and staffing have been especially harmful for women and Black workers, who are disproportionately employed in the state and local public sectors.

Black women face a persistent pay gap, including in essential occupations during the pandemic

This year, Black Women’s Equal Pay Day arrives 10 days earlier than in 2020 (August 13). If this seems inconsistent with current realities, it is. That’s because the August 3, 2021, date is based on the comparison of median annual earnings for full-time, year-round workers reported in the 2020 Annual Social and Economic Supplement of the Current Population Survey (CPS). Since the reference year in that survey is the previous year—2019—the earlier date is more a statement about pay equity during the pre-COVID period of historically low unemployment than the impact of the pandemic.

Based on hourly wages available for 2020, the pandemic’s effect on pay inequality in 2020 is challenging to interpret since job losses were concentrated among low-wage occupations, which has the effect of skewing the distribution toward a higher average that is less representative of the workforce as a whole. These lower-paying jobs were concentrated in leisure and hospitality and education and health services—industries that employ a disproportionate share of women.

In fact, the pandemic’s effect on pay equity during 2020 is less about a relative difference in dollars per hour and more a matter of a disproportionate share of women—and Black women in particular—becoming unemployed and thus wageless. Nearly one in five Black women (18.3%) lost their jobs between February 2020 and April 2020, compared with 13.2% of white men (see figure below). As of June 2021, Black women’s employment was still 5.1 percentage points below February 2020 levels, while white men were down 3.7 percentage points.

Worker protection agencies need more funding to enforce labor laws and protect workers

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the widespread dangers and injustices that workers face every day. For too long, workers have been forced to work in unsafe conditions, suffered from excessive wage theft, and been subjected to discrimination and harassment. While laws aimed at deterring these workplace abuses already exist, enforcement efforts have been woefully insufficient because the agencies tasked with protecting workers are chronically under-resourced. As Congress and the Biden administration work on budget spending and COVID-19 recovery legislation, there is an urgent opportunity to correct these inadequacies in our labor law system and boost funding for enforcement agencies.

The Department of Labor (DOL) and the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) enforce major worker protection laws, including the Fair Labor Standards Act, the Occupational Safety and Health Act, and the National Labor Relations Act. These statutes guarantee U.S. workers a minimum wage, a safe and healthy workplace, and the right to collective bargaining, respectively, but weak enforcement has led to pervasive and repeated violations of these laws. Despite inflation, a growing workforce, and increasingly complex workplaces, funding for agencies like the Wage and Hour Division (WHD), Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and the NLRB has largely remained stagnant over the last decade, as shown in Figure A.

As Arkansas and Missouri see a rise in COVID-19 cases, more economic protections are needed

Key takeaways:

- As the Delta variant of COVID-19 spreads throughout the United States, Arkansas and Missouri are facing an even more dramatic spike in COVID-19 cases, in part due to lower vaccination rates. This puts many at risk and may contribute to long-term economic problems in the region.

- To mitigate these effects, Missouri and Arkansas policymakers must take immediate action to strengthen public health and the economy, including:

- Expanding Medicaid and eliminating barriers to benefits.

- Recommitting to the federal expansion of unemployment benefits to cushion the economic harm as business disruptions grow.

- Enacting paid sick leave and paid family and medical leave.

As COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations begin to rise again across the country, some states are more vulnerable than others. Neighboring states Missouri and Arkansas are in the middle of a serious COVID-19 spike along with Louisiana, Florida, and Mississippi. The number of cases per capita in the two states—about 52 new cases daily per 100,000 residents in Arkansas and 40 per 100,000 residents in Missouri—is more than twice the national average of 19. The seven-day rolling average of deaths in the two states is rising rapidly and is three times the national average. Mercy Hospital in Springfield, Missouri, ran out of ventilators over the Fourth of July weekend. Hospitals across the state of Arkansas are already reaching maximum capacity—even as a record number of COVID-19 hospitalizations are anticipated in the coming weeks.

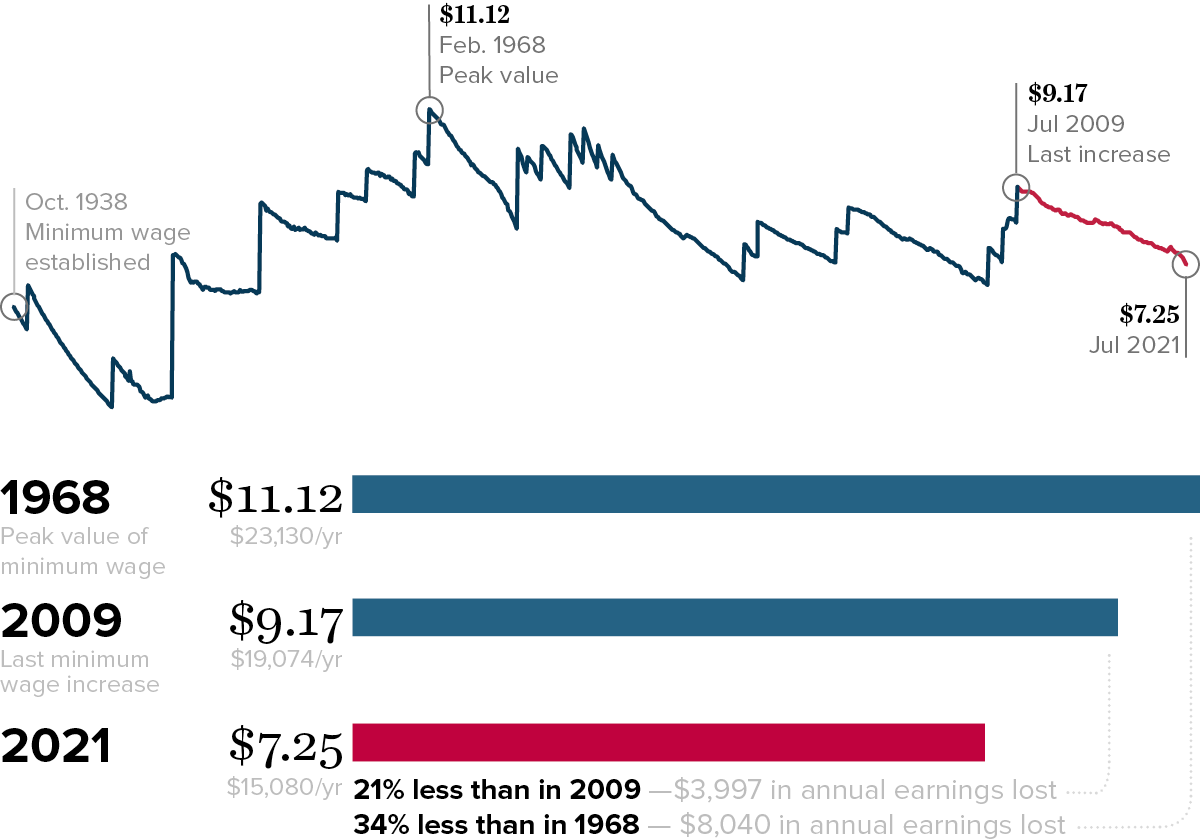

The minimum wage has lost 21% of its value since Congress last raised the wage

Saturday marks 12 years since the last federal minimum wage increase on July 24, 2009, the longest period in U.S. history without an increase. In the meantime, rising costs of living have diminished the purchasing power of a minimum wage paycheck. A worker paid the federal minimum of $7.25 today effectively earns 21% less than what their counterpart earned 12 years ago, after adjusting for inflation.

After the longest period in history without an increase, the federal minimum wage in 2021 was worth 21% less than 12 years ago—and 34% less than in 1968. : Real value of the minimum wage (adjusted for inflation)

Notes: All values are in June 2021 dollars, adjusted using the CPI-U-RS

Source: Fair Labor Standards Act and amendments

As a result of Congressional inaction, over two dozen states and several cities have raised their minimum wage, including 11 states and the District of Columbia that have adopted a $15 minimum wage. These higher wage standards have increased the earnings of low-wage workers, with women in minimum wage-raising states seeing the largest pay increases. In the rest of the country, however, states have punished low-wage workers by refusing to raise pay standards. As many as 26 states have gone so far as to pass laws prohibiting local governments from raising their minimum wage.

The farmworker wage gap continued in 2020: Farmworkers and H-2A workers earned very low wages during the pandemic, even compared with other low-wage workers

Key takeaways:

- More than two million farmworkers were deemed “essential” amid the pandemic in order to sustain food supply chains, but the latest wage data show that farmworkers were not rewarded adequately: They earned just $14.62 per hour on average in 2020, far less than even some of the lowest-paid workers in the U.S. labor force.

- At this wage rate, farmworkers earned just under 60% of what comparable workers outside of agriculture made in 2020—a wage gap that was virtually unchanged since the previous year. They also earned less than workers with the lowest levels of education.

- The wage paid to most farmworkers with H-2A visas—known as the Adverse Effect Wage Rate (AEWR)—was even lower, with a national average of $13.68 per hour. (The AEWR is based on a mandated wage standard that varies by region and is intended to prevent underpayment.) But many H-2A farmworkers earned far less in some of the biggest H-2A states. In Florida and Georgia—where a quarter of all H-2A jobs were located in 2020—H-2A workers were paid the lowest state AEWR, at $11.71 per hour.

- Farmworkers are employed in one of the most hazardous jobs in the entire U.S. labor market and suffer very high rates of wage and hour violations, and the majority of farmworkers who are unauthorized migrants or on H-2A visas are even worse off, with limited labor rights and heightened vulnerability to wage theft and other abuses due to their immigration status. Congress should take immediate action to improve labor standards for all farmworkers and provide migrant farmworkers with a path to citizenship.

Near the start of the pandemic in 2020, numerous work and travel restrictions were implemented in the United States to slow the spread of COVID-19. But for most workers, including farmworkers, options like remote work were either not permitted or not feasible. The more than two million farmworkers who grow, harvest, and pack the crops that end up on grocery store shelves were deemed “essential” and expected to work to keep food supply chains up and running.

Were those farmworkers ultimately rewarded and valued for their massive contributions to society? It appears not—the latest wage data show that farmworkers continued to earn far less than even some of the lowest-paid workers in the U.S. labor force, which suggests their important work continues to be undervalued. This post reviews the wages that farmworkers earned in 2020 relative to other comparable sets of workers.

Worker-led state and local policy victories in 2021 showcase potential for an equitable recovery

What new world of work can be built from the crisis COVID-19 created for workers and working-class communities? Some 2021 state and local policy victories are providing early answers. Across the country, workers are organizing to win policy changes aimed at strengthening labor standards, raising wages, reversing long-standing race and gender-based exclusions from labor rights, and building power to ensure these gains are not short-lived. The following examples of campaign and policy victories from recent legislative sessions are just the beginning of what is necessary to create a world where all work truly has dignity.

Building worker power and protecting the right to organize at the state level

Long before COVID-19, the right to unionize varied widely depending on a worker’s occupation, race, gender, or ZIP code. Union workers had more job security during the pandemic, and more workers are expressing interest in gaining a voice on the job through a union, yet legal exclusions and steep barriers to organizing mean that far too few workers have access to the union protections they want and need. Because federal labor law still excludes farmworkers, domestic workers, and public-sector workers from coverage, states are left to determine whether millions of disproportionately Black, Brown, immigrant, and women workers in front-line occupations will have legal rights to pursue a union contract.

This year, educators, care workers, farmworkers, and public servants acutely affected by the pandemic worked to accelerate the passage of proposals to expand labor rights and defend existing rights from ongoing state legislative attacks. Colorado enacted a groundbreaking, comprehensive Farmworker Bill of Rights extending full rights to organize unions and collectively bargain to 40,000 farmworkers across the state in a significant effort to advance worker power at the state level. The legislation also includes new workplace safety protections, rights to minimum wage and overtime pay, anti-retaliation protections, rest and meal breaks, and other minimum standards that have long covered workers in other sectors.

Care workers are deeply undervalued and underpaid: Estimating fair and equitable wages in the care sectors

The Biden administration has made large investments in care work—both child care and elder care—key planks in its American Jobs Plan (AJP) and American Families Plan (AFP). These investments would be transformative, and a greater public role in providing this care work can make the U.S. economy fairer and more efficient. The administration has also recognized the need to pay workers in these sectors higher wages—which are sorely needed—but setting a fair wage standard for care workers presents unique challenges.

For a variety of systemic reasons, including racism, misogyny, and xenophobia, there has never been a set of institutions that has managed to carve out decent wages and working conditions in care work. For example, the average hourly wages for home health care and child care workers are $13.81 and $13.51, respectively, which is roughly half the average hourly wage for the workforce as a whole. So, unlike in sectors like construction, a “prevailing wage” standard would just cement the industrywide insufficient wages currently experienced in care work.

But just because it’s challenging doesn’t mean it’s impossible to establish strong wage standards in this sector. All wages in the U.S. economy are politically and socially determined, but given that care work is heavily publicly financed, care wages are especially determined by political decisions (via commission or omission). As a result, there is a strong administrative responsibility and opportunity to set equitable wages in this sector. This research memo outlines a number of ways to improve the wage standard for care workers and is a preview to a forthcoming, more comprehensive research report.

Civil monetary penalties for labor violations are woefully insufficient to protect workers

Key takeaways:

- Workers’ rights and safety violations receive significantly lower fines than financial and corporate law violations. And in many cases, these violations involve no monetary penalty at all.

- Because workers’ rights and safety violations result in such low financial penalties, these fines function as the cost of doing business rather than as deterrents.

- The ineffective nature of workers’ rights enforcement often leads to repeated workers’ rights and safety violations with little incentive for employers to improve conditions.

Civil monetary penalties—fines imposed when a law or regulation is violated—are enforcement tools. Agencies utilize them to enforce statutes and regulations, and the minimum and maximum civil penalties may be established administratively or by statute. By examining civil monetary penalties for violations of various key federal laws, we find a striking pattern: Workers’ rights and safety violations are assigned a significantly lower penalty value than violations of other laws—characteristic of a system that unjustly undervalues workers. While employers and corporate officials face significant civil monetary penalties for breaking the law related to consumer finance, lobbying, and insider trading regulations, violations of fundamental labor and worker protection laws involve only minimal civil monetary penalties or even no monetary penalty at all.

Policymakers cannot relegate another generation to underresourced K–12 education because of an economic recession

Key takeaways:

- Federal education funding and additional recovery funds targeted to education during recessions can help if they are sufficiently large and are sustained for long enough.

- During the Great Recession, federal funding and additional recovery funds targeted to public K–12 education through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act provided an initial and critical counterbalance to the defunding brought about by the recession, but these funds were phased out far too prematurely.

- Nationally, total real revenue per student lagged behind the pre-recession level, on average, for eight school years after the onset of the last economic downturn.

- The reductions in total revenue per student were not uniform across districts: High-poverty districts and their students experienced the biggest shortfalls—and a very sluggish recovery.

As Congress debates the appropriate amount of investments needed to boost the economic recovery from the COVID-19-induced recession, we can learn a lot by carefully looking at the decisions made in the aftermath of the Great Recession of 2007–2009. One of the clearest lessons of that period is that spending by the federal government largely dictated the amount of economic suffering for those hit the hardest. When that spending falls short of what is needed, some groups never fully recover.

School finance deserves a place in this discussion. Federal support to education plays a critical role in filling recession-induced fiscal gaps that open at the state and local levels, and maintaining education funding during economic downturns contributes to a faster and fuller economic recovery. As we discuss in this post, if federal investments in public education had been larger, sustained as needed, and allocated in a way that channeled further assistance to districts serving larger shares of low-income students, they would have better assisted our students, schools, and communities in the aftermath of the Great Recession.

May Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey shows job openings held steady and quits dropped

Below, EPI senior economist Elise Gould offers her initial insights on today’s release of the Jobs and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) for May. Read the full Twitter thread here.

The layoffs rate continued to trend downwards while the hires rate softened and the quits rate fell. It’s clear the monthly data exhibits some volatility, but the labor market over the last few months continues to move in the right direction.

2/n pic.twitter.com/NBeut1IAIp— Elise Gould (@eliselgould) July 7, 2021

June jobs report shows strong growth and the promise of recovery: Initial comments from EPI economists

EPI economists offer their initial insights on the June jobs report below. They see strong growth in employment, especially in leisure and hospitality—the numbers do not signal a big labor shortage. The economy appears to be on its way to a full recovery by the end of 2022.

From economist and director of EPI’s Program on Race, Ethnicity, and the Economy (@ValerieRWilson)

Read the full Twitter thread here.

The 850k jobs added in June reflects lifting of more COVID-19 restrictions in time for summer, no indication of labor shortage, and on pace to reach pre-COVID unemployment rate by end of 2022. 1/n

— Valerie R Wilson (@ValerieRWilson) July 2, 2021

Job and wage growth do not point to an economywide labor shortage

Highlights: Labor shortage

- The available data suggest that we’re seeing a relatively brisk adjustment to a large and positive economic demand shock, not an economywide labor shortage.

- In a measure of wage growth that controls for composition bias—the Atlanta Wage Growth Tracker—wage growth in the first 15 months following the COVID-19 economic shock has been comparable to the weak wage growth seen during the 2001 and 2008 recessions.

- Job growth by industry is very well predicted simply by the size of the jobs deficit that remained from the COVID shock—in fact, job growth in leisure and hospitality has been a bit higher than one would expect given the size of the COVID-19 hit to that industry.

Monthly job growth over the past three months has averaged 540,000, a pace that would see the economy hit pre-COVID measures of labor market health by the end of 2022. While recovery can’t come soon enough for U.S. workers, if we do hit this target of pre-COVID labor market health by the end of 2022 it will constitute a recovery that is roughly five times as fast as that following the last downturn (the Great Recession of 2008–2009, when reattaining pre-recession unemployment rates took a full decade).

Disappointing Supreme Court decision makes it harder for farmworkers to unionize

Today, the U.S. Supreme Court published its decision in Cedar Point Nursery v. Hassid, a case involving an employer challenge to a California regulation that allows union representatives to visit the property of agricultural employers—in narrowly tailored and time-limited circumstances—to carry out efforts to organize the hundreds of thousands of California farmworkers who work in hazardous and low-paying jobs and who suffer disproportionately high rates of wage and hour violations.

In a disappointing 6–3 decision, the Court’s conservative justices ruled that the California regulation constitutes a per se physical taking of the employer’s property, which in practical terms means union organizers will no longer have the right to access the farms where farmworkers are employed.

The vast majority of farmworkers across the country are not protected by the National Labor Relations Act—the federal law that enshrines the right of workers to join and form unions. In an attempt to fill that gap for farmworkers in California, over four decades ago the state’s legislature passed the Agricultural Labor Relations Act (ALRA), which established collective bargaining rights for farmworkers, and then-governor Jerry Brown signed it into law in 1975. The ALRA’s access regulation enables organizers to visit the properties where farmworkers are employed, allowing the law to be implemented and have real meaning for workers.

Inflation—sources, consequences, and appropriate policy remedies

Several very good primers were recently written on how to think about inflation in the coming months. But as the reaction to monthly price inflation numbers that ever tick above a 2% annualized rate continues to be disproportionately angst-ridden, another one may be useful.

Assessing this week’s data and the ongoing debate about inflation and economic “overheating” requires an understanding of at least four key points:

- The source of inflationary pressure is crucial to assessing how policy should respond. Inflation coming from the labor market because workers are empowered enough to secure wage increases that run far ahead of the economy’s long-run capacity to deliver them (that is, productivity growth) is the only source of inflation that should ever spur a contractionary macroeconomic policy response (either smaller budget deficits or higher interest rates). This type of inflation is what worries about “overheating” center on.

- Other sources of inflationary pressure are far more likely to be transitory and hence should not spur a contractionary policy response.

- Inflation in the prices of commodities is often volatile and driven largely by global markets. Such price increases are likely to hinge on idiosyncratic drivers like weather changes, oil field discoveries, or rapid growth in large economies outside the United States. This kind of inflation should not spur a contractionary response. These price increases are not driven by economic “overheating”; engineering an economic “cooling” by reducing budget deficits or raising interest rates will not stop them—but it will cause a lot of collateral damage in slowing growth within the United States.

- Inflation driven by very large relative price changes is also highly likely to be transitory and should not be met with a contractionary macroeconomic policy response.

- Arguing that inflation stemming from many sources should not be met with a contractionary policy response does not mean that this type of inflation is good, or even just benign. Such inflation often does reduce typical workers’ living standards. But to be effective, anti-inflation policy must address such types of inflation with tailored measures, not across-the-board macroeconomic austerity.

- Spillovers of inflation that begin outside the labor market but spark inflation driven by wage-price spirals are highly unlikely given the extremely weak bargaining position and leverage of typical U.S. workers in recent decades. This degraded bargaining position also suggests that unemployment rates might reach far lower levels than they did in past decades before spurring wage growth sufficient to drive excess price inflation.

A real ‘party of the working class’ wouldn’t attack the Affordable Care Act

A number of high-profile Republicans in recent years have tried to claim that they have become the “party of the working class.” Nothing exposes this as false as clearly as the GOP’s unrelenting attacks on the Affordable Care Act (ACA)—legislation that was imperfect but still an enormously important advance in the U.S. welfare state.

The latest attack is another court case that made its way to the Supreme Court (California v. Texas)—which could have a ruling as soon as Thursday. Legal merits of the case aside (there were essentially none), the economic fallout of the case if it is decided in the plaintiffs’ favor would be profound, as the requested remedy is the abolition of the entire ACA.

The ACA was in some ways hugely complicated, but can be boiled down to five major undertakings:

- Strengthening employer-provided health insurance with mandates like no lifetime caps on benefits paid and an allowance for adults up to the age of 26 to be covered on parents’ plans;

- Providing needed regulation for the “nongroup” health insurance market (the market for people who can’t get insurance through their employer or through existing government programs);

- Providing subsidies to make purchasing nongroup plans more affordable for many;

- Paying for states to expand their Medicaid programs significantly; and

- Raising taxes on high incomes to pay for its spending provisions.