Some states and localities will be better prepared to fight a possible recession because of how they used ARPA fiscal recovery funds

With today’s news that GDP declined in the first quarter of 2025, there are increasing signs that the economy is headed in the wrong direction, with the risks of a recession and higher unemployment on the rise. Working families will face increased challenges in a recession. As always, government policies can do a lot to alleviate its worst impacts. During the COVID-19 recession, the Biden administration’s American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) helped fuel a fast recovery. The fiscal recovery funds provided to state and local governments were critical to that recovery. Some of those states, cities, and counties did more than just support an economic recovery—they made wise investments that will be help lessen the harms of the next recession in their communities. Read more

Too many workers die on the job every year. Trump’s attacks on OSHA will kill more.

This Monday marked Workers Memorial Day, an annual international day of remembrance of workers who have died on the job, as well as a day of action to continue the fight for workplace safety. An estimated 140,587 U.S. workers died from hazardous working conditions in 2023, according to a new AFL-CIO report. This amounts to roughly 385 workplace-related deaths a day. While mourning these lives lost, there is also reason to fear this death toll will only rise due to aggressive Trump administration attacks on basic health and safety protections long taken for granted in most U.S. workplaces.

Trump has spent his first 100 days in office waging a war against workers, firing tens of thousands of federal workers, and slashing the wages of hundreds of thousands of workers on federal contracts. He has also issued dozens of executive orders to roll back or review existing regulations, including an order directing agencies—including the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA)—to eliminate 10 existing protections before enacting any new guidelines.

Above all, Trump has empowered Elon Musk—a billionaire whose own companies are under investigation for dozens of serious health and safety violations—to destroy and disable already understaffed federal agencies that prevent workplace deaths and injuries. The administration’s damaging actions include:

- effectively eliminating the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), the sole agency responsible for research that informs OSHA policymaking with evidence-based assessments of injury and fatality risks and actionable guidance for employers to use to improve safety;

- closing down 11 OSHA offices in states with the highest workplace fatality rates;

- eliminating 34 offices of the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA), which protects coal miners from hazards like black lung disease;

- pausing a new rule on silica exposure to prevent coal miner disease and death from silicosis;

- allowing Musk to access sensitive OSHA data that could compromise ongoing investigations of alleged violations (including analysis of hazards that caused fatalities) and increase the risk of retaliation against injured workers and whistleblowers.

Cuts to SNAP benefits will disproportionately harm families of color and children

Republicans in Congress and the Trump administration passed a budget blueprint to pay for tax cuts that overwhelmingly favor rich households at the expense of working people. Communities of color will be disproportionately impacted by these potential cuts. In addition to targeting Medicaid—we highlighted how Medicaid cuts would be especially harmful for people of color and children here—the budget resolution also tees up Congress to slash $230 billion in agricultural spending over the next 10 years. Finding cuts that large will almost certainly require reducing nutrition spending by cutting the country’s largest food assistance program, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which is run out of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA).

These draconian cuts, along with the troubling momentum to add even more stringent work requirements to benefits like SNAP and Medicaid, will leave economically vulnerable families who depend on these support systems exposed to even more hardship during a time of unprecedented economic mismanagement, chaos, and uncertainty. Read more

What to watch for in this week’s labor market data: Will there be signs of widespread economic distress?

As the Trump administration pursues a deeply chaotic policy agenda, key labor market data haven’t yet revealed strong signs of economic weakness, but other sources indicate growing recessionary pressures. Consumer expectations are more pessimistic about inflation and unemployment, manufacturing and construction activity are declining, the stock market has fallen and remains volatile, and GDP forecasts look grim. These “softer” measures could take time to reflect in the official jobs data, particularly at the national level. This week’s data releases—including the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) tomorrow, unemployment insurance claims on Thursday, and the jobs report on Friday—should provide more clarity.

The federal minimum wage is officially a poverty wage in 2025

In 2025, the federal minimum wage is officially a “poverty wage.” The annual earnings of a single adult working full-time, year-round at $7.25 an hour now fall below the poverty threshold of $15,650 (established by the Department of Health and Human Services guidelines). The limitations of how the federal government calculates poverty understate how far the minimum wage is from economic security for workers and their families.

Set at an adequate level, the minimum wage is one of the strongest policy tools for improving the economic security of low-wage workers, and an effective tool at lowering poverty. Yet instead of addressing this massive hole in our economy’s social safety net by working to raise the minimum wage, congressional Republicans are pushing policies like imposing work requirements on safety net programs and cutting Medicaid. Supporters of these proposals characterize them as tools to incentivize work and protect the dignity of work, but these policies fail to account for the nature of low-wage work in our economy. Instead, they stand to deepen hardship for low-income workers with no economic upside for working people or the larger economy.

How should we assess and characterize worker wage growth in recent decades?

Key takeaways:

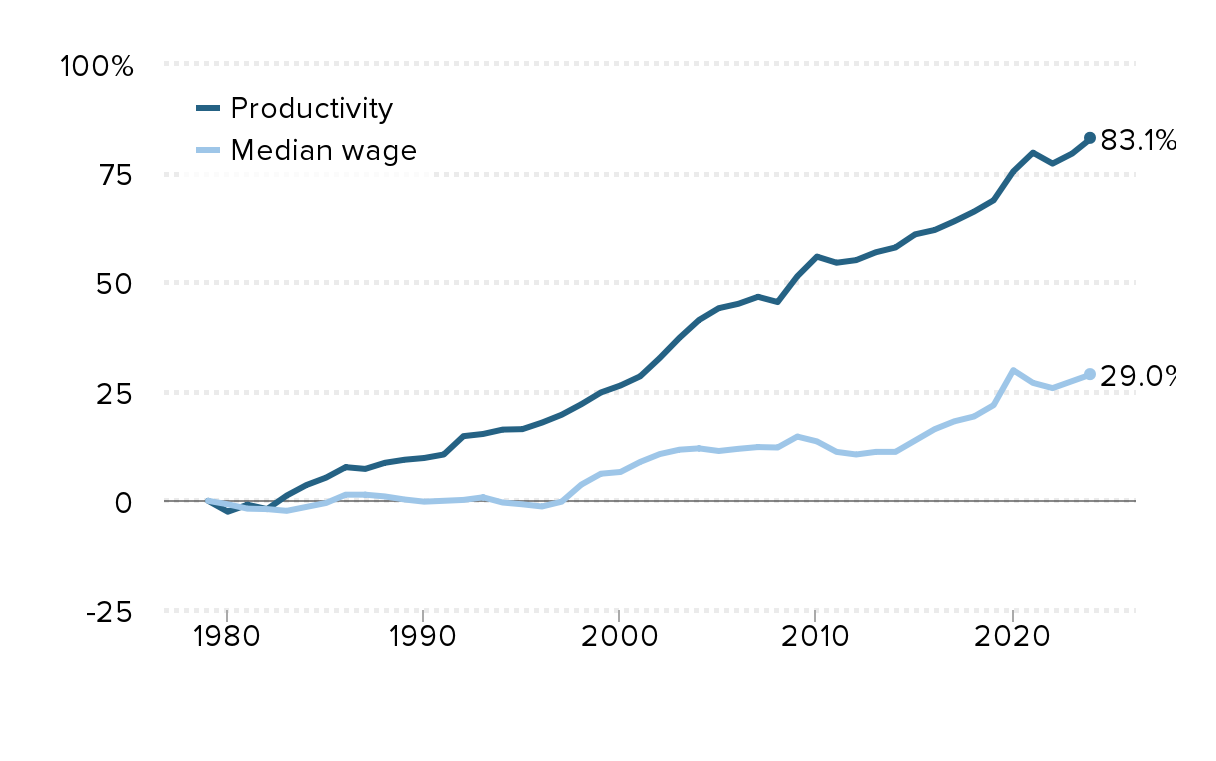

- Real median wages grew too slowly and only in fits and starts over the last 45 years. This pattern was even starker for low-wage workers.

- Median wages grew only one-third as fast as economy-wide productivity growth.

- Wage growth was reasonably healthy during tight labor markets but almost zero in other years.

- While tight labor markets persisted only in the clear minority of years since 1979, the last decade has been largely characterized by persistent low unemployment and this has been good for wage growth.

- Unfortunately, the Trump administration’s chaotic and harmful policy agenda threatens these recent gains.

Our recently released State of Working America wages report includes new data on wages through 2024. Cumulative median wage growth was just 29% since 1979—or less than 0.6% per year on average.

This was far slower than the economy’s potential to deliver wage growth for all workers. In fact, as Figure A shows, median wage growth was only one-third as fast as how much could have been delivered to all workers by growing productivity. This disconnect between pay and productivity is why we now refer to the post-1979 trajectory of wages as “wage suppression” rather than “wage stagnation.”

Median wage growth greater than zero, but still lags potential growth since 1979: Cumulative growth rate of real median wages and productivity

| Median wage | Productivity | |

|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 1980 | -0.8% | -2.5% |

| 1981 | -1.8% | -0.9% |

| 1982 | -1.9% | -1.9% |

| 1983 | -2.3% | 1.2% |

| 1984 | -1.4% | 3.6% |

| 1985 | -0.5% | 5.3% |

| 1986 | 1.4% | 7.7% |

| 1987 | 1.4% | 7.3% |

| 1988 | 1.0% | 8.7% |

| 1989 | 0.3% | 9.4% |

| 1990 | -0.2% | 9.8% |

| 1991 | 0.0% | 10.6% |

| 1992 | 0.2% | 14.8% |

| 1993 | 0.8% | 15.3% |

| 1994 | -0.4% | 16.3% |

| 1995 | -0.8% | 16.4% |

| 1996 | -1.3% | 17.9% |

| 1997 | -0.2% | 19.7% |

| 1998 | 3.7% | 22.1% |

| 1999 | 6.2% | 24.8% |

| 2000 | 6.6% | 26.4% |

| 2001 | 8.9% | 28.5% |

| 2002 | 10.7% | 32.7% |

| 2003 | 11.7% | 37.3% |

| 2004 | 12.0% | 41.4% |

| 2005 | 11.4% | 44.1% |

| 2006 | 11.9% | 45.1% |

| 2007 | 12.3% | 46.7% |

| 2008 | 12.2% | 45.5% |

| 2009 | 14.7% | 51.4% |

| 2010 | 13.6% | 55.9% |

| 2011 | 11.2% | 54.5% |

| 2012 | 10.6% | 55.1% |

| 2013 | 11.2% | 56.9% |

| 2014 | 11.2% | 58.0% |

| 2015 | 13.8% | 61.0% |

| 2016 | 16.4% | 62.0% |

| 2017 | 18.2% | 64.0% |

| 2018 | 19.3% | 66.2% |

| 2019 | 21.9% | 68.8% |

| 2020 | 29.9% | 75.4% |

| 2021 | 27.0% | 79.7% |

| 2022 | 25.8% | 77.2% |

| 2023 | 27.4% | 79.5% |

| 2024 | 29.0% | 83.1% |

Source: Median wage data from Economic Policy Institute, State of Working America Data Library, "Hourly wage percentiles - Real hourly wage (2024$)" and "Productivity and pay, real dollars per hour (2024$)".

Too often, the bar for policy success on wage growth has been set at anything greater than zero. So long as literal wage stagnation was avoided, discussion about the urgent task of boosting typical workers’ wage growth could be forestalled.

The unlawful abduction and imprisonment of Kilmar Abrego Garcia puts all workers in peril

The Trump administration’s unlawful removal of Kilmar Armando Abrego Garcia to a prison in El Salvador—and willful defiance of court orders to facilitate his return—are demonstrating a flagrant disregard for due process that puts all U.S. residents in danger. The case has become the biggest test of the rule of law so far in the second Trump administration and illustrates the threats now facing all working people if the administration’s abuses of power are left unchecked.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents detained Abrego Garcia—a union sheet metal apprentice and father of three from Maryland—on March 12 while he was driving home from work. Despite the fact that Abrego Garcia had a work permit and court-ordered protection from deportation to El Salvador, the Trump administration flew him there and put him in a prison infamous for inhumane conditions and violence—known as CECOT and operated by Salvadoran dictator Nayib Bukele—in defiance of an initial court order, along with 238 others. Three-fourths of the people on that flight had no criminal record, according to major media investigations. Irrespective of their individual backgrounds, every single person on the flight was illegally removed from the U.S. and imprisoned for life without an opportunity to have their cases heard in court.

The Department of Justice admitted in court that removing Abrego Garcia from the U.S. was unlawful (what attorneys for the U.S. have called an “administrative error”), but the Trump administration has refused to take steps to bring him home. In the Oval Office last week, Trump and Bukele even seemed to gleefully bond over Abrego Garcia’s fate, with Trump announcing his intent to send U.S. citizens to CECOT next.

How Trump’s erasure of environmental data is endangering communities of color

President Trump has weakened the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) by understaffing, underfunding, and restricting its work—leaving vulnerable communities at higher risk of environmental discrimination and racism. Within weeks of taking office, Trump revoked several key Biden-era executive orders on climate, public health, and environmental justice. While some of Trump’s actions have been reversed, his attacks toward the EPA remain unrelenting—continuing a pattern of sweeping environmental rollbacks that defined his first term. This time, however, his efforts are more targeted and dangerous, striking directly at the intersection of climate and race. Through data censorship and removal, the Trump administration is dismantling key tools for advancing environmental justice and protecting communities from environmental discrimination.

Trump’s gutting of public health institutions is setting the stage for our next crisis

What is happening?

The Trump administration is gutting our national public health infrastructure in real time, setting the stage for the next public health crisis. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), tasked with “protecting the health of all Americans and providing essential human services, especially for those who are least able to protect themselves,” is set to see a reduction in staff from 82,000 to 62,000 (a decrease of almost 25%) alongside major cuts to spending on contracts.Read more

Trump is putting crucial school funding at risk by dismantling the Department of Education: See how much federal funding your school district could lose

Last month, President Trump ordered Secretary of Education Linda McMahon to move forward with plans to close the Department of Education (ED). While this move is illegal and has been met with litigation, it shows the Trump administration’s hostility to public education and raises deep concerns about how public school districts across the country will be able to properly fund schools in the face of potential steep federal cuts.

The Trump administration occasionally makes vague promises that it will maintain current federal resources flowing to public schools, but this is far from assuring. Today’s federal education aid is extremely well-targeted toward high-need districts, and even if the level of federal aid to states is maintained, it’s not clear that it would remain as well-targeted.

Currently, a large share of ED funding goes to high-poverty districts through Title I funds and to special education programs through IDEA programs. These resources are crucial in offsetting the differences in local funding between low- and high-income districts, which rely heavily on property taxes. Over the last few years, COVID relief packages bolstered federal funding to public schools, with the Elementary and Secondary Schools Emergency Relief fund helping districts recover from learning losses that occurred during the pandemic. In 2022, districts received 14.0% of their total revenue, on average, from federal sources.

To get a sense of how this federal money is distributed, we used data from the National Center for Education Statistics to calculate district-level estimates of federal revenue shares, the amount of Title I and IDEA funds each district receives, and the federal funding equivalent in the number of full-time teachers and staff. The results of this analysis can be seen in Figure A. Federal funding is crucial for schools across the country—the median amount a school district receives is $2.69 million. Federal funds make up less than 20% of a district’s budget in most cases (82%), but some districts rely on the federal government to contribute a much larger share of their funding—as much as 71.4% at the highest end.