The importance of revenue revisited: Minimizing the drag of austerity

Via Ezra Klein comes a must-read leaked memo from Senate Budget Committee Chairwoman Patty Murray (D-Wash.) to Senate Democrats ahead of fashioning a Senate Budget Resolution. It’s an excellent chronology of the deficit reduction enacted in the 112th Congress—a hefty $2.4 trillion expected to take effect and $3.6 trillion if sequestration goes into effect—and the looming phases of the Beltway budget fights following the American Taxpayer Relief Act (i.e., the lame-duck budget fight, or ATRA for short).1

Klein hones in on tables depicting the fundamentally unbalanced nature of deficit reduction in the 112th Congress: Ignoring sequestration, 70 percent of policy deficit reduction measures (i.e., excluding additional debt service savings) enacted came from spending cuts as opposed to revenue, and if sequestration takes effect as scheduled, the share of spending cuts ratchets up to 80 percent. Murray’s memo contrasts these ratios with a 51 percent revenue share proposed by the Simpson-Bowles Co-Chairs’ report and 52 percent in the Senate’s bipartisan “Gang of Six” proposal. Hence Murray’s conclusion:

“Revenue Must be Included in Any Deal. Tackling our budget challenges requires both responsible spending cuts and additional revenue from those who can afford it most.”

She’s absolutely right, but the memo hits only on the budgetary half of why compositional balance is important. Accepting on face value that the 113th Congress will pursue more deficit reduction measures (more forthcoming from us on this premise)—at the very least replacing sequestration in chunks or entirety—including progressive revenue is critical for minimizing the economic drag of austerity. Read more

Huge disparity in funding for immigration enforcement vs. labor standards

In a new, well-documented report, Immigration Enforcement in the United States: The Rise of a Formidable Machinery, the Migration Policy Institute (MPI) calculated that the government’s price tag for immigration enforcement in 2012 was $18 billion. The report made headlines by highlighting the fact that this figure amounts to 24 percent more than it costs to fund the five main U.S. law enforcement agencies combined. But MPI offered another important juxtaposition in the report that has failed to receive much attention: the abysmally low level of funds the government commits to enforcing labor standards and protecting the rights of workers in the United States.

MPI reviewed the budgets of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and the Labor Department’s Wage and Hour Division (WHD) and Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), concluding that in 2010, the “combined budgets for [the] three main federal labor standards regulatory agencies was $1.1 billion … compared to the $17.2 billion budgets for DHS’s two immigration enforcement agencies.” Analyzing the most recent federal budget data available, EPI has found that even when including additional federal agencies whose primary purpose is to enforce labor standards (the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA), the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP), and the National Mediation Board (NMB)), in 2012, the total amount Congress appropriated to enforce labor laws and regulations amounted to only $1.6 billion—about 9 percent of what was spent enforcing immigration laws last year.

The labor enforcement agencies are staffed at only a fraction of the levels required to adequately fulfill their missions.Read more

The congressional GOP has smothered a more rapid economic recovery

PBS’ Frontline has an interesting piece on the GOP response to President Obama’s election in 2008, reporting that, “After three hours of strategizing, they decided they needed to fight Obama on everything.”

Part of this “everything” was the efforts of the new administration to end the Great Recession and restore the economy back to full health. From the start, the GOP sought to block measures that a wide swath of economists agreed would provide help to boost the economy and bring down unemployment. This obstructionism has been a constant theme throughout the past four years, and it continues today.

Congressional Republicans have made it clear that they intend to use every bit of leverage they can to force cuts to domestic spending in the coming year. This leverage includes threats to not raise the statutory debt ceiling and/or force a federal government shutdown after March 27, when the standing appropriations continuing resolution (CR) expires. This, of course, would represent the long-promised repeat of the spring and summer of 2011, when congressional Republicans secured over $500 billion in domestic spending cuts in CR fights and another $2.1 trillion in spending cuts in exchange for incrementally raising the debt ceiling by an equivalent amount—better known as the Budget Control Act (BCA) of 2011.

The BCA cuts have already done damage, and will all-but-surely slow growth in the rest of 2013 as well. The various components of the BCA accounted for about one-third of the total fiscal drag exerted by the major components of the “fiscal cliff” that was facing Congress ahead of the lame duck budget deal. And the components of the BCA account for 48 percent of the remaining fiscal drag unaddressed by the deal—a drag that is poised to shave 1.0 percentage point from real GDP growth in 2013. House Republicans have voted to replace the Defense cuts contained within the sequester—again rapidly approaching, following its postponement to March—in it with deeper domestic spending cuts, leaving a drag of 0.8 percentage points from the BCA for 2013, all while threatening to use the debt ceiling and CR as leverage to get their way.

If this ideologically driven objective of deeply cutting spending is met, this will represent just one more way that the GOP Congress has managed to delay full recovery from the Great Recession. The evidence continues to pile up Read more

Are the job polarization data robust?

This post is the fourth in a short series that assesses the role of technological change and job polarization in wage inequality trends.

In an earlier post, John Schmitt showed that “job polarization”—the expansion of low- and high-wage occupations at the expense of occupations in the middle—did not occur in the 2000s, (and therefore could not be responsible for rising wage inequality in the 2000s). In this post, I examine how well the key figures at the heart of the “job polarization” analysis really fit the underlying data. I begin with a closer look at the data for the 1990s, the decade that appears to conform most closely to the patterns implied by the job polarization explanation for wage inequality.

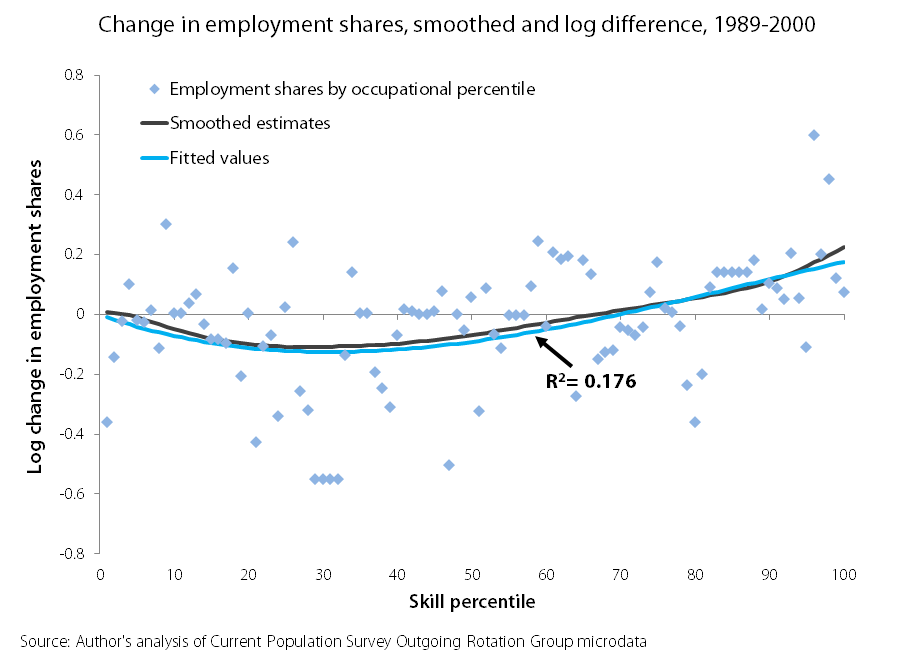

In a recent piece critical of research myself, John, and Larry Mishel are doing on technology and wages, Dylan Matthews makes a lot of our interpretation of the following chart for the 1990s. The chart, which we prepared for a paper presented at a conference earlier this month, shows the change between 1989 and 2000 in the share of total employment in 100 different occupation groups arrayed by their average wage level (labeled “skill percentile”):

The two lines are statistically smoothed versions of the individual data points, which appear as blue diamonds. Both lines show a rough U-shape that is consistent with the standard story of job polarization: employment increases were largest at the top and bottom of the skill distribution and smallest in the broad middle. Read more

What we read today

Here’s some of the thought-provoking content that EPI’s research team enjoyed reading today:

- “The increasingly isolated GOP” (The Plum Line)

- “Sequester And Shutdown Could Be More Likely Than A Fight Over The Debt Ceiling” (Capital Gains and Games)

- “Why Grandma Owes More on Her Credit Cards Than You do” (Demos)

- “Crumbling Infrastructure, Crumbling Democracy: Infrastructure Privatization Contracts and Their Effects on State and Local Governance” (Employment Policy Research Network)

Apple’s own data reveal 120,000 supply-chain employees worked excessive hours in November

To its credit, Apple is now posting monthly information tracking the extent to which employees in its supply chain are working less than its standard of 60 hours per week. The introductory language to this information states: “Ending the industry practice of excessive overtime is a top priority for Apple in 2012.” The accompanying graph itself, however, contains data from Jan. 2012 through Nov. 2012 and suggests otherwise. Not only has Apple failed to end this practice, but progress has significantly reversed in recent months.

Apple’s code of supplier conduct sets a maximum work week of 60 hours, with an exception clause, discussed below. Eyeballing Apple’s graph indicates (Apple only provides a specific number for November, so visual approximation is necessary):

- In Jan. 2012, about 16 percent of the workers in Apple’s supply chain worked more hours than Apple’s maximum standard. This proportion diminished through August, when approximately 3 percent of these workers had work weeks that exceeded this standard.

- But the proportion of workers meeting the standard dropped precipitously since then, presumably reflecting the increased intensity of work to produce and meet iPhone 5 demand.

- In November, 12 percent of the workers in Apple’s supply chain that are being tracked worked more than the 60-hour standard. This was the worst monthly compliance rate of the year, with the exception of January. More than one million workers are being tracked by Apple, so the 12 percent translates to more than 120,000 workers in their supply chain working excessive hours. Read more

AARP comes out against COLA cut

AARP unveiled new research from its Middle Class Security Project yesterday, with related papers focusing on topics ranging from rising health care costs to credit card debt. At the release, AARP CEO Barry Rand gave a rousing speech, coming out strongly against a proposed cut in the Social Security cost-of-living adjustment (COLA), echoing a similar stance by the New York Times this Sunday. Rand focused on the need for both solvency and adequacy, emphasizing that Americans don’t want Social Security reform to be part of deficit reduction talks and were willing to contribute more to strengthen the program.

Policy director Debra Whitman, an economist and Social Security advocate Rand hired to replace the too-quick-to-compromise John Rother, said most Americans were surprised at how low Social Security benefits were—less than $14,000 per year on average. In the report, Whitman and her co-authors highlight the fact that benefits would be cut further for future retirees with a scheduled increase in the normal retirement age to 67, equivalent to an across-the-board benefit cut. As a result of this and other negative trends, the report estimates that three out of 10 middle-income workers will become low-income retirees.

This might seem like an obvious place to call for shoring up Social Security benefits for the middle class—or at least halting their decline. But though Whitman and many of her colleagues may prefer to close Social Security’s projected shortfall with revenue increases, AARP continues to avoid ruling out additional benefit cuts or endorsing specific revenue proposals, such as lifting the cap on taxable earnings. This might seem like a wise PR move, given the flak AARP gets for drawing a line in the sand (even when it actually hasn’t). But, like President Obama’s administration, AARP will be attacked as intransigent by some critics no matter how conciliatory they are, so they might as well stake out a clear position, backed up by the facts in this report.Read more

Occupation employment trends and wage inequality: What the long view tells us

This post is the third in a short series that assesses the role of technological change and job polarization in wage inequality trends.

The discussion of job polarization—the expansion of high and low-wage occupations while middle-wage occupations decline—and its role in driving wage inequality would benefit from a longer examination of occupational change and technology’s impact.

“Occupational upgrading” has been going on for 60 years or more. By occupational upgrading, we mean the erosion of employment in blue-collar and, more recently, pink-collar (administrative/clerical) occupations and the corresponding employment expansion of high wage, professional and managerial white-collar occupations. The share of employment in low-wage, service occupations (food preparation, janitorial/cleaning services, personal care and services) has actually been relatively stable for many decades and remained a small—roughly 15 percent—share of total employment.

The bottom line for the discussion of the role that technologically-driven occupation trends have played in generating wage inequality is that occupational upgrading has been occurring for decades, through periods of both rising and falling wage inequality and through both rising and falling median real wage growth. In our view, this makes occupational employment shifts a poor candidate for explaining the rise in wage inequality since 1979. Read more

International tests show achievement gaps in all countries, with big gains for U.S. disadvantaged students

Corrections were made to this post on Jan. 30. For explanations of the corrections, see the full report summarized in this posting.

In a new EPI report, What do international tests really show about U.S. student performance?, we disaggregate international student test scores by social class and show that the commonplace condemnation of U.S. student performance on such tests is misleading, exaggerated, and in many cases, based on misinterpretation of the facts. Ours is the first study of which we are aware to compare the performance of socioeconomically similar students across nations.

Some critics, disturbed by the unsophisticated way in which policymakers and pundits use international tests to condemn American student performance, have commented that American students in relatively affluent states, like Massachusetts or Minnesota, or students in schools where few students are from low-income families, perform as well or better than average students in the highest scoring countries. But while such comparisons are well-intended, they can’t tell us much because a proper comparison would be between affluent states in the U.S., and affluent provinces or prefectures in other countries, or between schools with little poverty in the U.S. and schools with little poverty in other countries. Critics have not previously had data by which such comparisons can properly be made.

MORE: Authors’ response to OECD/PISA reaction to their report (PDF)

AUDIO: Authors speak with the press about their report (MP3)

Yet both of the major international tests—the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) and the Program on International Student Assessment (PISA)—eventually publish not only average national scores but a rich database from which analysts can disaggregate scores by students’ socioeconomic characteristics, school composition, and other informative criteria. Examining these can lead to more nuanced conclusions than those suggested from average national scores alone. Read more

What we read today

Here’s some interesting content that EPI’s research team recommends today:

- “Our Economic Pickle” (New York Times)

- “This Week in Poverty: Smiley Calls for White House Conference on US Poverty” (The Nation)

- “The Low Politics of Low Growth” (New York Times)

- “Much Ado about Nothing on Obama’s White Guy Appointees” (New America Media)

- “Misguided Social Security ‘Reform‘” (New York Times)

Missing in action: Growth and shared prosperity

Two articles in the Sunday New York Times, appearing side-by-side, together told the fundamental truth that our current discussion of economic policy ignores: Generating greater economic growth and ensuring that middle-class wages grow with productivity are essential for restoring shared prosperity and achieving our budget goals.

Steven Greenhouse’s piece, “Our Economic Pickle,” states:

“Federal income tax rates will rise for the wealthiest Americans, and certain tax loopholes might get closed this year. But these developments, and whatever else happens in Washington in the coming debt-ceiling debate, are unlikely to do much to alter one major factor contributing to income inequality: stagnant wages.”

The article notes, “Wages have fallen to a record low as a share of America’s gross domestic product” and quotes Harvard’s Larry Katz appropriately summarizing the situation: “What we’re seeing now is very disquieting.”

This is not totally new, as shown by the data from The State of Working America that Greenhouse cites: “From 1973 to 2011Read more

Timing matters: Can job polarization explain wage trends?

This post is the second in a short series that assesses the role of technological change and job polarization in wage inequality trends.

The recently posted introduction of Assessing the job polarization explanation of growing wage inequality, a paper I wrote with Heidi Shierholz and John Schmitt, has started to raise some interest in the topic so it’s worth surfacing some of the issues and evidence it contains. John has already written a blog post on the fact that job polarization (the expansion of low and high-wage occupations and the shrinkage of middle-wage occupations) did not occur in the 2000s and that recent occupational employment shifts are clearly not driving recent wage trends. Our paper raises two sets of empirical issues. First, we point out that the evidence that job polarization caused wage polarization (growing inequality in the top half of the wage distribution but stable or shrinking inequality in the bottom half) in the 1990s is entirely circumstantial, relying on the two trends (employment and wage polarization) occurring at the same time without demonstration of any linkage. Second, the paper challenges whether occupational employment trends drive key wage patterns.

This post explores the point that one piece of missing evidence from the “job polarization is causing wage inequality” story is around the timing of employment and wage changes. That is, all of the evidence presented so far on job polarization relates to wage and employment trends over big chunks of time (1979–89 and 1989–99 or even 1974–88 and 1988–2008) and there has not been an examination of year-by-year trends. This is important because Read more

Job polarization in the 2000s?

This post was originally published in the Center for Economic and Policy Research’s blog. It will be the first in a short series that assesses the role of technological change and job polarization in wage inequality trends.

In a recent post at Wonkblog, Dylan Matthews takes a fairly dim view of a new paper that Larry Mishel, Heidi Shierholz, and I have written on the role of technology in wage inequality. Matthews raises several issues, but I want to focus right now on a key point that he missed: proponents of the “job polarization” view of technological change provide no evidence that the framework actually works in the 2000s. Larry, Heidi, and I will cover other issues in additional blog posts.

In his piece, Matthews focused on our criticisms of the ability of the job polarization approach to explain wage developments in the 1990s. I’ll leave the discussion of the 1990s for another day, but the more important issue for contemporary policy discussions is whether the framework is helpful at all for the last decade.

Since the occupation-based “tasks framework” that lies behind the academic research on job polarization is widely considered in the economics profession to be the best available technology-based explanation for wage inequality, Larry, Heidi, and I take the lack of evidence for this framework in the 2000s as support for our view that other policy-related factors are what is really driving inequality. We also think that if this purportedly unified framework doesn’t work well for the 2000s, that it is likely not helpful for earlier periods either.

MORE FROM THE SERIES

LARRY MISHEL: Can job polarization explain wage trends?

LARRY MISHEL: Occupation employment trends and wage inequality

HEIDI SHIERHOLZ: Are the job polarization data robust?

But, even if you still think technology is the main or even an important culprit, we would argue that you need a new theory of technology that actually fits the facts of the 2000s.

This is a fairly long post and starts with some necessary background—necessary because there is a sizable gap between the way economists talk formally about “job polarization” and the way most of the public talks about the same issue. Read more

Don’t be fooled by Apple’s PR: Workers strike against sweatshop conditions

Students and Scholars Against Corporate Misbehaviour (SACOM) reports that on Jan. 10, workers at one of Foxconn’s China plants (in Fengcheng, Jiangxi Province) went on strike. The factory produces Apple’s iPhone connector and products for other companies. SACOM suggests the strike resulted from the sweatshop working conditions at the plant, poor pay, lack of union representation, health and safety violations, and general lack of respect for the workers. The resulting protest by more than 1,000 workers was met with a harsh crackdown, with water cannons and physical violence apparently used against the strikers. SACOM notes the contrast between the ongoing harsh conditions reported by workers and the often-rosy public relations campaign by Foxconn and Apple.

This report deserves careful attention. SACOM is a Hong Kong-based NGO that has enlisted workers in Apple’s Foxconn factories to report on life and work inside the giant complexes. It is the most credible source of information about conditions in Apple’s manufacturing plants in China. SACOM was the organization that first revealed the wave of suicides at Foxconn, the construction of suicide nets, Apple’s use of underage students on its production lines, the continuing use of students compelled to work at Foxconn under threat of being kicked out of school, grossly excessive overtime, and many other abuses.

Private-sector pension coverage fell by half over two decades

The most recent issue of the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Monthly Labor Review provides a wealth of interesting—and depressing—statistics about pension coverage in the United States. The BLS’ “visual essay” documents the decline in defined benefit pensions, which now cover 18 percent of private-sector workers, down from 35 percent in the early 1990s.

Household coverage is higher, as many married couples have at least one spouse covered under a plan. Thus, a separate household survey conducted by the Federal Reserve found that 31 percent of households were covered by a defined benefit pension in 2010, though this includes households with workers employed in the public sector as well as retirees and workers covered under plans from previous jobs who are no longer accruing benefits.1

Though many workers are now enrolled in 401(k) plans, these have proven to be a poor substitute, as the typical household approaching retirement has less than two years’ worth of income saved in these accounts. The Fed survey found that the median households aged 55–64 had an income of $55,000 and just $100,000 saved in a retirement account, if they had a retirement account at all. Read more

What we read today

Here’s some reading material for you from items EPI’s research team skimmed through today:

- “For Americans Under 50, Stark Findings on Health” (New York Times)

- “Public Goals, Private Interests in Debt Campaign” (New York Times)

- “The Debt Ceiling’s Escape Hatch” (New York Times)

- “Superfluous grades; StudentsFirst ranking considers performance last” (Center for Public Education)

Unpaid internships: Denying opportunities and exploiting young workers

Laura Rowley has an excellent response to the silly op-ed by Steve Cohen published in Tuesday’s Wall Street Journal. Cohen wrote that paying interns to deliver clothing for photo shoots, run copy machines, or clean the green room at a TV studio is dumb. The young people doing those jobs are not employees, according to Cohen; they’re simply auditioning.

Cohen admits that the grunt work he and his son did in separate internships at a law firm and a magazine was “boring, mindless, repetitious” and yet, “essential to the workings of our offices.” Nevertheless, Cohen says the chance to prove himself a good employee was so valuable to him, as was the exposure to a law office’s operations, that his employer shouldn’t have had to pay him even minimum wage.

Rowley accepts Cohen’s conclusion that his internship was valuable but says the experience shouldn’t be limited to people like Cohen (a former media executive) and his son, who can afford to work for free. What about the kids graduating from college with $50,000 of debt, or the children of factory workers or waitresses who can’t support their grown children in New York City? Should they be denied the audition, the exposure to interesting work environments, the chance to prove themselves? Read more

With friends like these: The carbon tax edition

I know that Thomas Friedman thinks he’s making the case for a carbon tax stronger by emphasizing that it addresses the dangers of both climate change and large federal deficits, but because he’s mixing an honest-to-goodness danger (climate change) with a phantom one (increased debt in the near term), it’s not clear to me he’s helping much. To paraphrase the blogger Daniel Davies, “Good ideas don’t need a lot of misleading arguments mobilized on their behalf.” (I’d like to include a link, but he has since shut down his blog and the post is not available.)

Nevermind that Friedman starts his column by invoking the “cliff” metaphor so common in fiscal policy debates these days, and then riffs off it to decry the mounting public debt of the United States. But [and imagine my hand slapping my forehead] surely everybody knows by now that the danger of the “fiscal cliff” is one of debt rising too slowly, right? And nobody disagrees about this.

The bigger problem is his outsized claim that a too-small ($20 per ton) carbon tax could cut 10-year deficits in half. That sounded high to me, so, I looked up the report he references. Read more

Michigan’s ‘right-to-work-for-less’ legislation: Bad for workers, undemocratic, fundamentally immoral

The Michigan “right-to-work” law that was enacted in December is bad public policy. Its supporters claim it will attract business to the state and lift incomes, though research shows the opposite is true.

By prohibiting contracts that require union-represented employees to pay dues, “right to work”—or, more accurately, “right to work for less”—gives workers a right to freeload, a right to accept the benefits of a union contract while paying nothing for the cost of organizing the union, winning the contract, or enforcing its terms. Employees can demand that the union represent them in a grievance while paying absolutely nothing for the cost of that representation. This enshrinement of freeloading was matched by the way the bill was passed—by a lame-duck legislature, without committee hearings, without an opportunity for amendment or public input.

In an amazing, impassioned speech, Rep. Brandon Dillon (D-Grand Rapids) condemned both the undemocratic way the right-to-work-for-less bill was jammed through the Michigan legislature and the immorality that animates it. Watch his short but powerful speech below:

Michelle Rhee gets a failing grade on her report card

Michelle Rhee and her misnamed school privatization organization, StudentsFirst, recently issued a report card on the nation’s schools that has been roundly criticized, and rightly so. Rhee ranks all 50 states and the District of Columbia by how closely they hew to her vision of school “reform,” which involves high stakes testing, maximizing the number of charter schools, expanding voucher programs that use tax dollars to pay for private schools, and eliminating teacher tenure and pension plans. Rhee is so keen to reduce the pensions of teachers and their reward for longevity that she makes their elimination an “anchor policy” and gives it triple weight in her ranking methodology.

She also cares deeply about and grades the states on removing school governance from local control and the influence of democratically elected school boards. She prefers giving governance instead to the kind of mayoral control or state control that put her in charge of the D.C. school system under Mayor Adrian Fenty. That gets triple weight, too.

Curiously, despite Rhee’s love of high stakes testing, student performance as measured by the gold-standard test of student achievement, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), plays no role in her ranking of the states. These “rankings” put Louisiana and Florida (both bottom 10 on the NAEP), for example, far ahead of high-achieving states like Massachusetts, Minnesota, and New Jersey, all of which ranked in the top three on the NAEP.

Doug Henwood took a close look at Rhee’s rankings and found they have a negative correlation with success on the NAEP: “[T]he higher the StudentsFirst score, the lower the NAEP reading score. The correlation on math is even worse, -0.25.”

When you consider that Rhee’s rankings actually punish states that limit class size, it’s easy to understand their negative correlation with achievement.

Rhee’s right-wing agenda of privatization, de-unionization, and the funneling of public tax dollars into corporate coffers is becoming clearer to the public—and perhaps even to her own staff. Coupled with her recent stumble over the shootings at the elementary school in Newtown, Conn., her reluctance to oppose a Michigan bill to allow concealed weapons in schools, and the PBS Frontline exposé about cheating scandals during her tenure as chancellor in D.C., Rhee and her agenda may be losing their glitz and appeal.

We can only hope so.

NYT story emphasizes Apple’s positive statements, obscures ongoing labor abuses

The New York Times and the reporters of its Dec. 26 story—“Signs of Changes Taking Hold in Electronics Factories in China”—deserve much credit for raising the profile of the abusive conditions faced by the workers making Apple products, helping to spur promises of reform. But the latest story, while portraying internal changes at Apple that could lead to reforms and describing the possibility that Apple and its competitors may advance a new manner of operating globally, provides surprisingly little evidence or analysis of the degree to which improvements have been made. It thus never gets to the heart of the matter: So far, Apple’s pledges of sweeping change have not been matched by major reforms in working conditions.

The vision

The vision painted by the story is one labor advocates, and presumably many Apple customers, share. When it comes to working hours, compensation, and other working conditions, Apple’s main supplier Foxconn will make the reforms necessary to raise standards dramatically, leading to a “ripple effect that benefits tens of millions of workers across the electronics industry.”

As ostensible evidence of Apple’s leadership and commitment to that vision, the article notes, for example, that Apple has hired 30 new staff members for its social responsibility unit and put two respected and influential former Apple executives in charge. The article also notes earlier and recent statements from Apple and Foxconn pledging to accomplish a great deal for factory workers.

The reality

The article is surprisingly thin, however, when it comes to assessing whether this vision is being fulfilled. The report includes a long vignette about the new, comfortable work chair provided to one Foxconn employee (in which the reporters argue that this helped lead her to view her job and her life prospects in a positive new manner). At other points, the article refers to some reductions in work hours, some safety improvements, a partial Foxconn response to ending the abuses of student interns, and some wage improvements. If all this sounds kind of fuzzy, that’s because it is. Read more

What we read today

Here’s some good content that EPI’s research team browsed through today:

- “Canada’s guest worker program could become model for U.S. immigration changes” (Washington Post)

- “Huge Amounts Spent on Immigration, Study Finds” (New York Times)

- “Is the Trillion-Dollar Platinum Coin Clever or Insane?” (TaxVox)

- “More bogosity from Michelle Rhee” (Left Business Observer)

- “A White House Meeting With Low-Income Americans” (The Nation)

Strengthening the EITC and raising the minimum wage should go hand-in-hand

Evan Soltas’ Friday column in Bloomberg misses some of the facts on the minimum wage, and presents a false choice between raising the minimum wage and expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). The crux of his argument is that even though raising the minimum wage would reduce inequality, likely provide some stimulus to the economy, and help to reduce poverty, liberal policymakers should not pursue it because the EITC allegedly does all this more effectively, and Republican lawmakers might be less opposed to an EITC expansion than they are to raising the federal minimum wage. Questions of political acceptance aside, the reality is that these two policy levers need each other.

There’s a critical relationship between the minimum wage and the EITC that Soltas seems to be missing. In spoken comments at a conference last year, my colleague Heidi Shierholz explained [emphasis added]:

The U.S. has two main policies designed to address the problem of low wages – the minimum wage and the EITC. The minimum wage provides a floor for the wages people get in the market, and through the tax system; the EITC provides subsidies to workers who earn low wages. The real value of the minimum wage has been allowed to erode and needs to be raised. What about the EITC? Read more

The Bush tax cuts are here to stay

As my colleague Larry Mishel wrote in a post last week, “Fighting to preserve social insurance (Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid) benefits that the broad middle class depends on and making the public investments we need for growth and equity requires winning the battle over more revenues in the budget negotiations ahead.” This task will prove far more difficult now that the Bush-era income tax rate cuts have been made permanent for all taxpayers earning less than $400,000 ($450,000 for joint filers), making them a permanent part of the legislative landscape moving forward.

The Bush tax cuts, passed in 2001 and 2003, were designed to sunset after 2010 so they could pass Congress through the reconciliation process. They were extended by President Obama through 2012 so as to not raise taxes during the recession/weak recovery; additionally, in exchange for extending them two years, Obama was able to negotiate the payroll tax holiday and the extension of Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC).

The most recent extension of these cuts has allowed conservative members of Congress (and others, like Grover Norquist) to claim victory on these tax cuts, which briefly expired on Dec. 31, 2012, only to be reinstated almost in full. Conservative representative Dave Camp (R-Mich.) summed up the situation by saying, “After more than a decade of criticizing these tax cuts, Democrats are finally joining Republicans in making them permanent.” Read more

What we read today

Here’s some of the interesting content that EPI’s research team browsed through today:

- “What does ‘not negotiating’ look like?” (The Plum Line)

- “How Washington Learned to Love Hostage-Taking” (The New Republic)

- “We don’t have a spending problem. We have an aging problem.” (Mother Jones)

- “Union-busting’s the secret filling inside Twinkie demise” (Orlando Sentinel)

At best, budget deal suggests decelerating anemic growth, labor market deterioration

Yesterday, my colleague Josh Bivens outlined the contours of this weekend’s 11th hour budget deal, concluding that Congress mostly monkeyed around with upper-income taxes—a politically contentious “fiscal cliff” component, but the least economically significant—leaving large swathes of scheduled fiscal restraint in place (or merely delayed a few months). For months, Josh and I have been arguing that the only real challenge facing Congress is the reality that the budget deficit closing too quickly—as it has been since mid–2010—threatens to push the economy into an austerity-induced recession. To this effect, “cliff” was a doubly misleading metaphor, as there was no single economic tipping point (underscored by President Obama signing the deal on Jan. 2, after the misguidedly hyped Jan. 1 “cliff plunge” had passed) and the legislated fiscal restraint was comprised of fully separable policies rather than an all-or-nothing dichotomy.

Viewed through the proper lens of avoiding premature austerity instead of compromising over tax policy for the top 2 percent of earners, Congress predictably failed to adequately moderate the pace of deficit reduction; short of sharply reorienting fiscal policy to accommodate accelerated recovery, U.S. trend economic growth will continue decelerating into 2013—slowing to anemic growth insufficient to keep the labor market just treading water.1 Absent substantial (seemingly remote) additional spending on public investment and transfer payments, the labor market will almost certainly deteriorate this year, regardless of what happens with sequestration and the pending debt ceiling fight. Read more

At $250B, costs of occupational injury and illness exceed costs of cancer

Occupational injuries and illnesses are overlooked contributors to the overall national costs of all diseases, injuries, and deaths. My recent study published in the Milbank Quarterly, “Economic Burden of Occupational Injury and Illness in the United States,” estimates these costs to be roughly $250 billion a year. This amount exceeds the costs of several other diseases, including cancer, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) for the same year.

The medical costs associated with occupational disease and injury ($67 billion) are very large, but are exceeded by the productivity costs ($183 billion), which include current and future lost earnings, fringe benefits, and home production (e.g., cooking, cleaning, rearing children and doing home repairs). These costs do not in any way account for the pain and suffering caused by this heavy toll of injury and illness. They also gloss over the horror of many of the truly gruesome workplace injuries that occur, including suffocation in corn siloes, drowning in sewer pipes, electrocution, and being ground up or crushed in machinery.

By contrast, Rosamond and colleagues1 have estimated the total cost of all cancers, including medical costs and lost production, to be $219 billion in 2007, $31 billion less than the combined cost of occupational injury and illness. Yet by most accountsRead more

More fiscal implications of a rising capital-share of income

Paul Krugman has been talking capital-bias and rising profit-shares recently. I was going to write about the implications of this for Social Security and Medicare, but he got there first. Below, I put some (very rough) numbers on how much a rising capital-share of income impacts the current financing of these programs.

The broad issue in a nutshell is that a rising share of overall income in recent years (even decades) has been accruing to owners of capital rather than to workers (or, if you like, accruing to owners of physical and financial capital rather than to owners of human capital). I might immodestly note that there are substantial sections on this topic in both the wages and the incomes chapter of The State of Working America, 12th Edition.

For now, I’ll just talk about some of the interesting tidbits from State of Working America and then sketch out one implication of these rising capital-shares for current fiscal policy debates.

First, the rise in the capital-share (again, the share of overall income claimed by owners of financial capital) really does seem to be happening. In State of Working America, we generally focus lots of attention on the corporate sector of the economy—a sector that accounts for about three-quarters of all private activity. For technical reasons, looking at trends within the corporate sector gives the clearest picture as to whether or not there really has been a substantial shift away from labor and toward capital owners. So has there been such a shift? Read more

So the ‘fiscal cliff’ has been addressed. The next priority should be to address the fiscal cliff.

The House and Senate passed a budget deal over the long weekend. Headlines reported it as a deal about the “fiscal cliff.” It wasn’t. It had some good and some bad elements, but it did nearly nothing to address the actual problem that was always meant to be described by the (terribly misleading, but also terribly sticky) phrase “fiscal cliff.” This problem is simply described: the still-weak U.S. economic recovery would have been damaged by the range of tax increases and spending cuts that were set to begin taking effect on Jan. 1, 2013, because these would have reduced overall demand in the U.S. economy, and weak demand remains the reason why unemployment is too high. And this problem was at-best deferred and at-worst ignored in the deal made this weekend (note that Iowa Sen. Tom Harkin has made this exact point).

We tried to describe this problem and even put numbers to each of the main components of the “fiscal cliff” in a September report. Some key punchlines of this analysis were that the problem posed by the “fiscal cliff” was that deficits would shrink too quickly in the coming year, and that while the Bush-era tax cuts for upper-income households were the most politically contested part of the cliff, it was the automatic spending cuts (including the end of extended unemployment insurance benefits) and the payroll tax increase that were, by far, the most economically damaging parts of the cliff. In fact, the fate of upper-income tax rates was almost irrelevant, one way or the other, to economic recovery in the coming year.

So what did Congress do in this deal? They mostly monkeyed around with upper-income tax rates. Which leaves the large bulk of the fiscal contraction set for the coming year still in place, or just temporarily delayed. In short, it is very odd to describe what happened over this long weekend as a deal that addressed the “fiscal cliff.” Read more

Let’s be straight on ‘investing in our middle class’

The White House continues to maintain that it is investing in the middle class going forward, yet this clearly is not true. This is important to understand as we move toward further budget deals that could make matters worse.

The White House statement on the fiscal deal says: “This agreement will also grow the economy and shrink our deficits in a balanced way – by investing in our middle class, and by asking the wealthy to pay a little more.” And an accompanying fact sheet claims: “this agreement ensures that we can continue to make investments in education, clean energy, and manufacturing that create jobs and strengthen the middle class.”

As my colleague Ethan Pollack has pointed out, this is inconsistent with President Obama’s frequent bragging point that his budget brings the non-security portion of the budget down to record-low levels—“the lowest level since President Eisenhower.” The fact is that if you lower domestic discretionary spending, you necessarily are reducing public investments in education, research and infrastructure. As a reminder, here’s Ethan’s analysis of infrastructure, education and research and development spending in the Obama Fiscal 2013 budget:

So, if we really want to invest in the middle class—as the president claims to—we will have to increase domestic discretionary spending, not cut it further as his most recent and prior budget requests have done (the president also offered to cut domestic discretionary spending by another $100 billion in the recent negotiations). Fighting to preserve social insurance (Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid) benefits that the broad middle class depends on and making the public investments we need for growth and equity requires winning the battle over more revenues in the budget negotiations ahead. We should all be clear about that.