Focus on the boom, not the slump—The Fed’s new policy framework needs to stop cutting recoveries short: EPI Macroeconomics Newsletter

Josh Bivens

For the past six months the Federal Reserve has been soliciting input to guide a reassessment of its “monetary policy framework.” This reassessment has been pegged to the 10-year anniversaries surrounding the financial crisis of 2008–09 and the Great Recession. While the Fed’s policy framework deserves much scrutiny, focusing too narrowly on what it could have done differently during the crisis and its aftermath would be a bad mistake.

The Fed failure that inflicted real damage on low- and middle-wage workers over recent decades was generally not insufficient effort in fighting recessions. Instead, the mistake was cutting short recoveries before they had maximized opportunities for employment and wage growth. In short, the time to worry about Fed actions that do not protect the interests of low- and middle-wage workers is during economic booms, not during slumps.

This newsletter explains why the Fed should keep the following points in mind as it undertakes its reassessment:

- Monetary policy is deeply asymmetric in its effects on macroeconomic stabilization. While interest rate increases work effectively to restrain growth, interest rate cuts provide very little boost to growth. This failure of interest rate cuts to spur growth—often analogized to “pushing on a string”—means that the Fed will frequently need help in fighting recessions. The limited effectiveness of Fed actions in spurring recovery from the Great Recession was not due to lack of effort, but to the inherent weakness of interest rate cuts as a tool.

- While it needs help in fighting recessions, the Federal Reserve has been given essential veto power on the issue of whether an economic expansion is proceeding too fast and needs to be restrained in the name of guarding against inflationary outbreaks. Too often the Fed puts the breaks on prematurely. These premature monetary policy contractions have cut recoveries short and kept unemployment unnecessarily high. This excess unemployment has deprived millions of people of potential work, and has been one of the single-largest factors explaining the disastrous wage stagnation afflicting the bottom 80 percent of the U.S. workforce for most of the post-1979 period. In fact, excess unemployment may well explain more than a third of the rise in wage inequality since 1979, and likely contributed to the redistribution of income from labor to capital owners. In short, excess unemployment is an absolutely primary source of the rise in American inequality.

The Fed did the right things during the Great Recession—but its tools are weak

Much of the discussion surrounding the reassessment of the Fed’s monetary framework focuses on whether the Fed used its institutional tools aggressively enough during the Great Recession and whether it needs new tools for future recessions. These are certainly questions worth considering, but they threaten to derail the debate from much more important ways that Fed decisions have undercut wage and job growth.

With regard to the Great Recession, the Fed responded earlier and more aggressively than any other major policymaking institution. It invented new tools on the fly, and the vast majority of these tools were used in the laudable aim of spurring faster recovery. These tools worked in the right direction, but their influence was weak due to the intrinsic weakness of interest rate cuts as levers to spur growth. Essentially, interest rate cuts make it cheaper for households and businesses and governments to take on debt to make purchases, but such cuts cannot force anybody to actually make these purchases. During recessions, when other influences often restrain economywide spending, the expansionary potential of lower interest rates can get swamped by these other factors. Importantly, the evidence documenting the weakness of interest rate cuts in spurring faster recovery is not driven entirely by episodes when the economy has hit the zero lower bound (ZLB) on interest rates. Instead, even when the Fed has room to cut interest rates further, these cuts deliver generally disappointing results in boosting growth. The ZLB just makes this weakness even more extreme.

Further, while the Fed took unprecedented policy actions to boost aggregate demand (spending by households, governments, and businesses) during and after the Great Recession, fiscal policy became historically contractionary over this period. In short, while there is some room for improvement in how the Fed approaches the next recession, there is little to suggest that the Fed’s fundamental framework for fighting recessions is flawed. But there is also little to suggest that Fed action alone will be enough to quickly end future recessions and restore full employment.

The Fed has too often cut recoveries short

The Fed’s actions throughout history have not always been supportive of economic recovery and growth in jobs and wages. Indeed, too often the Fed’s decisions have greatly exacerbated the economic struggles of low- and middle-wage workers. But the episodes when Fed action has damaged these workers have occurred when the economy is robustly expanding, not during recessions.

The Fed’s dual mandate instructs it to pursue the maximum level of employment consistent with stability in inflation. However, post-1979 its actions suggest that Fed policymakers have taken the inflation mandate more seriously than the full employment mandate. When an economic expansion pushes unemployment down, the Fed often fears that tighter labor markets will have workers demanding higher (nominal) wages. The intuition is that the best lever for workers to wring wage increases from employers is the threat (often implicit) that they’ll quit and find better-paid work elsewhere. This quit threat is far more credible during times of low unemployment.

Wage growth resulting from tight labor markets can potentially feed into price growth. In turn, workers may demand even higher nominal wages to make up for higher prices, allowing wage–price inflationary momentum to build. The policy recourse for the Fed to avoid this inflationary momentum is to raise interest rates to slow the expansion and stop the downward movement of unemployment.

But when is unemployment at the sweet spot of allowing all workers a chance at decent work and wage growth but not fostering unsustainable inflationary pressures? Nobody knows for sure beforehand. Efforts at empirically identifying the economy’s “natural rate of unemployment” are notoriously imprecise. Given this uncertainty, the Fed must exercise judgment in weighing the benefits of tighter labor markets against the risks of building up inflationary pressures. Far too often in the post-1979 period, Fed policymakers have been too worried about the inflation risks and not impressed enough by the full-employment benefits.

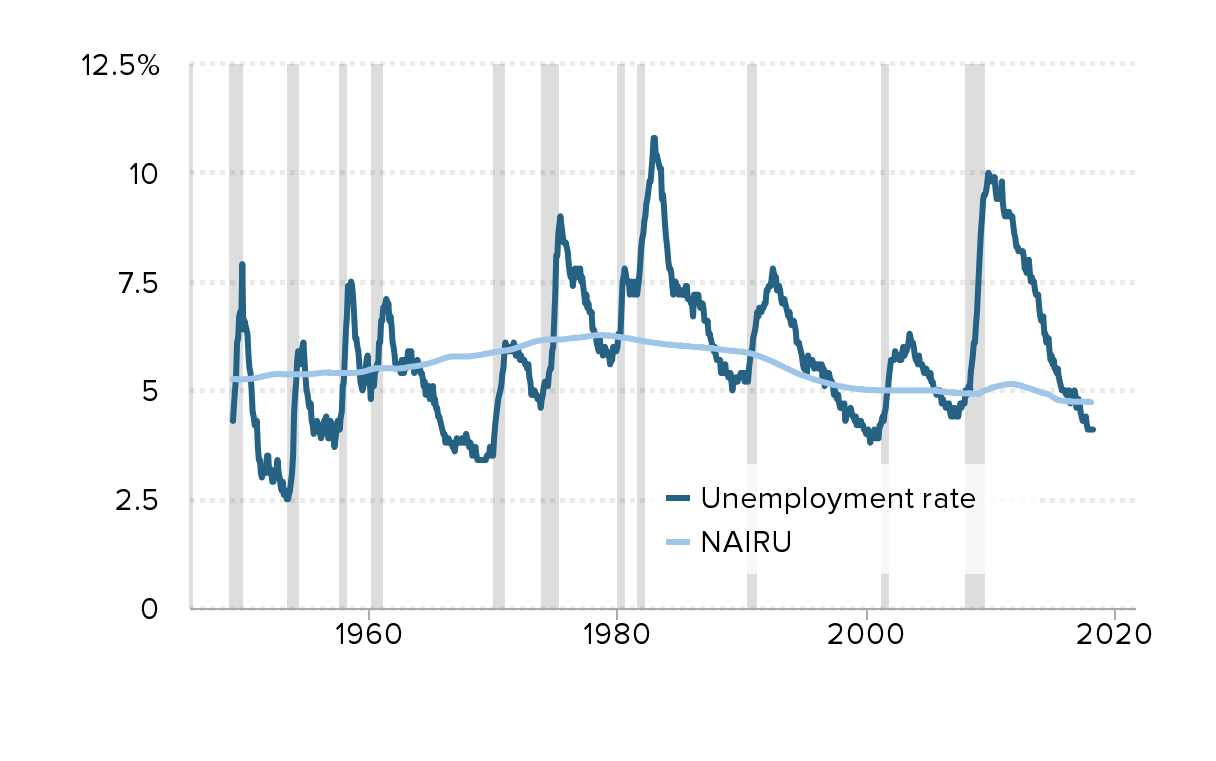

Figure A shows real-time estimates of the natural rate of unemployment and the actual unemployment rate. Set aside for a second the possibility that the estimated natural rate may itself be too conservative. The post-1979 Fed was far more likely to hold the economy above the natural rate than the Fed was in the 30 years before 1979. In the 30 years between 1949 and 1979, the actual unemployment rate was a cumulative 15 percentage points below the natural rate. But in the 28 years between 1979 and 2007, the actual unemployment rate was a cumulative 15 percentage points above the natural rate.

There has been insufficient vigilance in fighting unemployment since the late 1970s: Estimate of the natural rate of unemployment and actual unemployment, 1949–2018

| Month-Year | Unemployment rate | NAIRU |

|---|---|---|

| Jan-1949 | 4.3% | 5.26% |

| Feb-1949 | 4.7 | |

| Mar-1949 | 5.0 | |

| Apr-1949 | 5.3 | 5.26 |

| May-1949 | 6.1 | |

| Jun-1949 | 6.2 | |

| Jul-1949 | 6.7 | 5.25 |

| Aug-1949 | 6.8 | |

| Sep-1949 | 6.6 | |

| Oct-1949 | 7.9 | 5.25 |

| Nov-1949 | 6.4 | |

| Dec-1949 | 6.6 | |

| Jan-1950 | 6.5 | 5.26 |

| Feb-1950 | 6.4 | |

| Mar-1950 | 6.3 | |

| Apr-1950 | 5.8 | 5.26 |

| May-1950 | 5.5 | |

| Jun-1950 | 5.4 | |

| Jul-1950 | 5.0 | 5.27 |

| Aug-1950 | 4.5 | |

| Sep-1950 | 4.4 | |

| Oct-1950 | 4.2 | 5.28 |

| Nov-1950 | 4.2 | |

| Dec-1950 | 4.3 | |

| Jan-1951 | 3.7 | 5.29 |

| Feb-1951 | 3.4 | |

| Mar-1951 | 3.4 | |

| Apr-1951 | 3.1 | 5.31 |

| May-1951 | 3.0 | |

| Jun-1951 | 3.2 | |

| Jul-1951 | 3.1 | 5.33 |

| Aug-1951 | 3.1 | |

| Sep-1951 | 3.3 | |

| Oct-1951 | 3.5 | 5.34 |

| Nov-1951 | 3.5 | |

| Dec-1951 | 3.1 | |

| Jan-1952 | 3.2 | 5.36 |

| Feb-1952 | 3.1 | |

| Mar-1952 | 2.9 | |

| Apr-1952 | 2.9 | 5.37 |

| May-1952 | 3.0 | |

| Jun-1952 | 3.0 | |

| Jul-1952 | 3.2 | 5.38 |

| Aug-1952 | 3.4 | |

| Sep-1952 | 3.1 | |

| Oct-1952 | 3.0 | 5.38 |

| Nov-1952 | 2.8 | |

| Dec-1952 | 2.7 | |

| Jan-1953 | 2.9 | 5.37 |

| Feb-1953 | 2.6 | |

| Mar-1953 | 2.6 | |

| Apr-1953 | 2.7 | 5.37 |

| May-1953 | 2.5 | |

| Jun-1953 | 2.5 | |

| Jul-1953 | 2.6 | 5.37 |

| Aug-1953 | 2.7 | |

| Sep-1953 | 2.9 | |

| Oct-1953 | 3.1 | 5.37 |

| Nov-1953 | 3.5 | |

| Dec-1953 | 4.5 | |

| Jan-1954 | 4.9 | 5.37 |

| Feb-1954 | 5.2 | |

| Mar-1954 | 5.7 | |

| Apr-1954 | 5.9 | 5.37 |

| May-1954 | 5.9 | |

| Jun-1954 | 5.6 | |

| Jul-1954 | 5.8 | 5.37 |

| Aug-1954 | 6.0 | |

| Sep-1954 | 6.1 | |

| Oct-1954 | 5.7 | 5.37 |

| Nov-1954 | 5.3 | |

| Dec-1954 | 5.0 | |

| Jan-1955 | 4.9 | 5.37 |

| Feb-1955 | 4.7 | |

| Mar-1955 | 4.6 | |

| Apr-1955 | 4.7 | 5.38 |

| May-1955 | 4.3 | |

| Jun-1955 | 4.2 | |

| Jul-1955 | 4.0 | 5.38 |

| Aug-1955 | 4.2 | |

| Sep-1955 | 4.1 | |

| Oct-1955 | 4.3 | 5.39 |

| Nov-1955 | 4.2 | |

| Dec-1955 | 4.2 | |

| Jan-1956 | 4.0 | 5.40 |

| Feb-1956 | 3.9 | |

| Mar-1956 | 4.2 | |

| Apr-1956 | 4.0 | 5.41 |

| May-1956 | 4.3 | |

| Jun-1956 | 4.3 | |

| Jul-1956 | 4.4 | 5.41 |

| Aug-1956 | 4.1 | |

| Sep-1956 | 3.9 | |

| Oct-1956 | 3.9 | 5.41 |

| Nov-1956 | 4.3 | |

| Dec-1956 | 4.2 | |

| Jan-1957 | 4.2 | 5.40 |

| Feb-1957 | 3.9 | |

| Mar-1957 | 3.7 | |

| Apr-1957 | 3.9 | 5.40 |

| May-1957 | 4.1 | |

| Jun-1957 | 4.3 | |

| Jul-1957 | 4.2 | 5.40 |

| Aug-1957 | 4.1 | |

| Sep-1957 | 4.4 | |

| Oct-1957 | 4.5 | 5.40 |

| Nov-1957 | 5.1 | |

| Dec-1957 | 5.2 | |

| Jan-1958 | 5.8 | 5.40 |

| Feb-1958 | 6.4 | |

| Mar-1958 | 6.7 | |

| Apr-1958 | 7.4 | 5.40 |

| May-1958 | 7.4 | |

| Jun-1958 | 7.3 | |

| Jul-1958 | 7.5 | 5.40 |

| Aug-1958 | 7.4 | |

| Sep-1958 | 7.1 | |

| Oct-1958 | 6.7 | 5.40 |

| Nov-1958 | 6.2 | |

| Dec-1958 | 6.2 | |

| Jan-1959 | 6.0 | 5.41 |

| Feb-1959 | 5.9 | |

| Mar-1959 | 5.6 | |

| Apr-1959 | 5.2 | 5.42 |

| May-1959 | 5.1 | |

| Jun-1959 | 5.0 | |

| Jul-1959 | 5.1 | 5.43 |

| Aug-1959 | 5.2 | |

| Sep-1959 | 5.5 | |

| Oct-1959 | 5.7 | 5.45 |

| Nov-1959 | 5.8 | |

| Dec-1959 | 5.3 | |

| Jan-1960 | 5.2 | 5.48 |

| Feb-1960 | 4.8 | |

| Mar-1960 | 5.4 | |

| Apr-1960 | 5.2 | 5.49 |

| May-1960 | 5.1 | |

| Jun-1960 | 5.4 | |

| Jul-1960 | 5.5 | 5.51 |

| Aug-1960 | 5.6 | |

| Sep-1960 | 5.5 | |

| Oct-1960 | 6.1 | 5.51 |

| Nov-1960 | 6.1 | |

| Dec-1960 | 6.6 | |

| Jan-1961 | 6.6 | 5.51 |

| Feb-1961 | 6.9 | |

| Mar-1961 | 6.9 | |

| Apr-1961 | 7.0 | 5.51 |

| May-1961 | 7.1 | |

| Jun-1961 | 6.9 | |

| Jul-1961 | 7.0 | 5.51 |

| Aug-1961 | 6.6 | |

| Sep-1961 | 6.7 | |

| Oct-1961 | 6.5 | 5.51 |

| Nov-1961 | 6.1 | |

| Dec-1961 | 6.0 | |

| Jan-1962 | 5.8 | 5.50 |

| Feb-1962 | 5.5 | |

| Mar-1962 | 5.6 | |

| Apr-1962 | 5.6 | 5.50 |

| May-1962 | 5.5 | |

| Jun-1962 | 5.5 | |

| Jul-1962 | 5.4 | 5.51 |

| Aug-1962 | 5.7 | |

| Sep-1962 | 5.6 | |

| Oct-1962 | 5.4 | 5.51 |

| Nov-1962 | 5.7 | |

| Dec-1962 | 5.5 | |

| Jan-1963 | 5.7 | 5.53 |

| Feb-1963 | 5.9 | |

| Mar-1963 | 5.7 | |

| Apr-1963 | 5.7 | 5.54 |

| May-1963 | 5.9 | |

| Jun-1963 | 5.6 | |

| Jul-1963 | 5.6 | 5.55 |

| Aug-1963 | 5.4 | |

| Sep-1963 | 5.5 | |

| Oct-1963 | 5.5 | 5.56 |

| Nov-1963 | 5.7 | |

| Dec-1963 | 5.5 | |

| Jan-1964 | 5.6 | 5.57 |

| Feb-1964 | 5.4 | |

| Mar-1964 | 5.4 | |

| Apr-1964 | 5.3 | 5.59 |

| May-1964 | 5.1 | |

| Jun-1964 | 5.2 | |

| Jul-1964 | 4.9 | 5.60 |

| Aug-1964 | 5.0 | |

| Sep-1964 | 5.1 | |

| Oct-1964 | 5.1 | 5.62 |

| Nov-1964 | 4.8 | |

| Dec-1964 | 5.0 | |

| Jan-1965 | 4.9 | 5.64 |

| Feb-1965 | 5.1 | |

| Mar-1965 | 4.7 | |

| Apr-1965 | 4.8 | 5.66 |

| May-1965 | 4.6 | |

| Jun-1965 | 4.6 | |

| Jul-1965 | 4.4 | 5.69 |

| Aug-1965 | 4.4 | |

| Sep-1965 | 4.3 | |

| Oct-1965 | 4.2 | 5.71 |

| Nov-1965 | 4.1 | |

| Dec-1965 | 4.0 | |

| Jan-1966 | 4.0 | 5.74 |

| Feb-1966 | 3.8 | |

| Mar-1966 | 3.8 | |

| Apr-1966 | 3.8 | 5.76 |

| May-1966 | 3.9 | |

| Jun-1966 | 3.8 | |

| Jul-1966 | 3.8 | 5.78 |

| Aug-1966 | 3.8 | |

| Sep-1966 | 3.7 | |

| Oct-1966 | 3.7 | 5.78 |

| Nov-1966 | 3.6 | |

| Dec-1966 | 3.8 | |

| Jan-1967 | 3.9 | 5.78 |

| Feb-1967 | 3.8 | |

| Mar-1967 | 3.8 | |

| Apr-1967 | 3.8 | 5.78 |

| May-1967 | 3.8 | |

| Jun-1967 | 3.9 | |

| Jul-1967 | 3.8 | 5.78 |

| Aug-1967 | 3.8 | |

| Sep-1967 | 3.8 | |

| Oct-1967 | 4.0 | 5.78 |

| Nov-1967 | 3.9 | |

| Dec-1967 | 3.8 | |

| Jan-1968 | 3.7 | 5.78 |

| Feb-1968 | 3.8 | |

| Mar-1968 | 3.7 | |

| Apr-1968 | 3.5 | 5.79 |

| May-1968 | 3.5 | |

| Jun-1968 | 3.7 | |

| Jul-1968 | 3.7 | 5.80 |

| Aug-1968 | 3.5 | |

| Sep-1968 | 3.4 | |

| Oct-1968 | 3.4 | 5.81 |

| Nov-1968 | 3.4 | |

| Dec-1968 | 3.4 | |

| Jan-1969 | 3.4 | 5.82 |

| Feb-1969 | 3.4 | |

| Mar-1969 | 3.4 | |

| Apr-1969 | 3.4 | 5.84 |

| May-1969 | 3.4 | |

| Jun-1969 | 3.5 | |

| Jul-1969 | 3.5 | 5.85 |

| Aug-1969 | 3.5 | |

| Sep-1969 | 3.7 | |

| Oct-1969 | 3.7 | 5.86 |

| Nov-1969 | 3.5 | |

| Dec-1969 | 3.5 | |

| Jan-1970 | 3.9 | 5.88 |

| Feb-1970 | 4.2 | |

| Mar-1970 | 4.4 | |

| Apr-1970 | 4.6 | 5.89 |

| May-1970 | 4.8 | |

| Jun-1970 | 4.9 | |

| Jul-1970 | 5.0 | 5.90 |

| Aug-1970 | 5.1 | |

| Sep-1970 | 5.4 | |

| Oct-1970 | 5.5 | 5.91 |

| Nov-1970 | 5.9 | |

| Dec-1970 | 6.1 | |

| Jan-1971 | 5.9 | 5.92 |

| Feb-1971 | 5.9 | |

| Mar-1971 | 6.0 | |

| Apr-1971 | 5.9 | 5.93 |

| May-1971 | 5.9 | |

| Jun-1971 | 5.9 | |

| Jul-1971 | 6.0 | 5.95 |

| Aug-1971 | 6.1 | |

| Sep-1971 | 6.0 | |

| Oct-1971 | 5.8 | 5.97 |

| Nov-1971 | 6.0 | |

| Dec-1971 | 6.0 | |

| Jan-1972 | 5.8 | 6.00 |

| Feb-1972 | 5.7 | |

| Mar-1972 | 5.8 | |

| Apr-1972 | 5.7 | 6.02 |

| May-1972 | 5.7 | |

| Jun-1972 | 5.7 | |

| Jul-1972 | 5.6 | 6.05 |

| Aug-1972 | 5.6 | |

| Sep-1972 | 5.5 | |

| Oct-1972 | 5.6 | 6.07 |

| Nov-1972 | 5.3 | |

| Dec-1972 | 5.2 | |

| Jan-1973 | 4.9 | 6.10 |

| Feb-1973 | 5.0 | |

| Mar-1973 | 4.9 | |

| Apr-1973 | 5.0 | 6.12 |

| May-1973 | 4.9 | |

| Jun-1973 | 4.9 | |

| Jul-1973 | 4.8 | 6.14 |

| Aug-1973 | 4.8 | |

| Sep-1973 | 4.8 | |

| Oct-1973 | 4.6 | 6.15 |

| Nov-1973 | 4.8 | |

| Dec-1973 | 4.9 | |

| Jan-1974 | 5.1 | 6.16 |

| Feb-1974 | 5.2 | |

| Mar-1974 | 5.1 | |

| Apr-1974 | 5.1 | 6.17 |

| May-1974 | 5.1 | |

| Jun-1974 | 5.4 | |

| Jul-1974 | 5.5 | 6.17 |

| Aug-1974 | 5.5 | |

| Sep-1974 | 5.9 | |

| Oct-1974 | 6.0 | 6.17 |

| Nov-1974 | 6.6 | |

| Dec-1974 | 7.2 | |

| Jan-1975 | 8.1 | 6.17 |

| Feb-1975 | 8.1 | |

| Mar-1975 | 8.6 | |

| Apr-1975 | 8.8 | 6.17 |

| May-1975 | 9.0 | |

| Jun-1975 | 8.8 | |

| Jul-1975 | 8.6 | 6.17 |

| Aug-1975 | 8.4 | |

| Sep-1975 | 8.4 | |

| Oct-1975 | 8.4 | 6.18 |

| Nov-1975 | 8.3 | |

| Dec-1975 | 8.2 | |

| Jan-1976 | 7.9 | 6.19 |

| Feb-1976 | 7.7 | |

| Mar-1976 | 7.6 | |

| Apr-1976 | 7.7 | 6.20 |

| May-1976 | 7.4 | |

| Jun-1976 | 7.6 | |

| Jul-1976 | 7.8 | 6.21 |

| Aug-1976 | 7.8 | |

| Sep-1976 | 7.6 | |

| Oct-1976 | 7.7 | 6.21 |

| Nov-1976 | 7.8 | |

| Dec-1976 | 7.8 | |

| Jan-1977 | 7.5 | 6.22 |

| Feb-1977 | 7.6 | |

| Mar-1977 | 7.4 | |

| Apr-1977 | 7.2 | 6.23 |

| May-1977 | 7.0 | |

| Jun-1977 | 7.2 | |

| Jul-1977 | 6.9 | 6.24 |

| Aug-1977 | 7.0 | |

| Sep-1977 | 6.8 | |

| Oct-1977 | 6.8 | 6.25 |

| Nov-1977 | 6.8 | |

| Dec-1977 | 6.4 | |

| Jan-1978 | 6.4 | 6.26 |

| Feb-1978 | 6.3 | |

| Mar-1978 | 6.3 | |

| Apr-1978 | 6.1 | 6.27 |

| May-1978 | 6.0 | |

| Jun-1978 | 5.9 | |

| Jul-1978 | 6.2 | 6.27 |

| Aug-1978 | 5.9 | |

| Sep-1978 | 6.0 | |

| Oct-1978 | 5.8 | 6.27 |

| Nov-1978 | 5.9 | |

| Dec-1978 | 6.0 | |

| Jan-1979 | 5.9 | 6.26 |

| Feb-1979 | 5.9 | |

| Mar-1979 | 5.8 | |

| Apr-1979 | 5.8 | 6.26 |

| May-1979 | 5.6 | |

| Jun-1979 | 5.7 | |

| Jul-1979 | 5.7 | 6.25 |

| Aug-1979 | 6.0 | |

| Sep-1979 | 5.9 | |

| Oct-1979 | 6.0 | 6.24 |

| Nov-1979 | 5.9 | |

| Dec-1979 | 6.0 | |

| Jan-1980 | 6.3 | 6.23 |

| Feb-1980 | 6.3 | |

| Mar-1980 | 6.3 | |

| Apr-1980 | 6.9 | 6.22 |

| May-1980 | 7.5 | |

| Jun-1980 | 7.6 | |

| Jul-1980 | 7.8 | 6.21 |

| Aug-1980 | 7.7 | |

| Sep-1980 | 7.5 | |

| Oct-1980 | 7.5 | 6.20 |

| Nov-1980 | 7.5 | |

| Dec-1980 | 7.2 | |

| Jan-1981 | 7.5 | 6.19 |

| Feb-1981 | 7.4 | |

| Mar-1981 | 7.4 | |

| Apr-1981 | 7.2 | 6.17 |

| May-1981 | 7.5 | |

| Jun-1981 | 7.5 | |

| Jul-1981 | 7.2 | 6.16 |

| Aug-1981 | 7.4 | |

| Sep-1981 | 7.6 | |

| Oct-1981 | 7.9 | 6.15 |

| Nov-1981 | 8.3 | |

| Dec-1981 | 8.5 | |

| Jan-1982 | 8.6 | 6.13 |

| Feb-1982 | 8.9 | |

| Mar-1982 | 9.0 | |

| Apr-1982 | 9.3 | 6.12 |

| May-1982 | 9.4 | |

| Jun-1982 | 9.6 | |

| Jul-1982 | 9.8 | 6.11 |

| Aug-1982 | 9.8 | |

| Sep-1982 | 10.1 | |

| Oct-1982 | 10.4 | 6.10 |

| Nov-1982 | 10.8 | |

| Dec-1982 | 10.8 | |

| Jan-1983 | 10.4 | 6.09 |

| Feb-1983 | 10.4 | |

| Mar-1983 | 10.3 | |

| Apr-1983 | 10.2 | 6.08 |

| May-1983 | 10.1 | |

| Jun-1983 | 10.1 | |

| Jul-1983 | 9.4 | 6.07 |

| Aug-1983 | 9.5 | |

| Sep-1983 | 9.2 | |

| Oct-1983 | 8.8 | 6.06 |

| Nov-1983 | 8.5 | |

| Dec-1983 | 8.3 | |

| Jan-1984 | 8.0 | 6.05 |

| Feb-1984 | 7.8 | |

| Mar-1984 | 7.8 | |

| Apr-1984 | 7.7 | 6.05 |

| May-1984 | 7.4 | |

| Jun-1984 | 7.2 | |

| Jul-1984 | 7.5 | 6.04 |

| Aug-1984 | 7.5 | |

| Sep-1984 | 7.3 | |

| Oct-1984 | 7.4 | 6.03 |

| Nov-1984 | 7.2 | |

| Dec-1984 | 7.3 | |

| Jan-1985 | 7.3 | 6.03 |

| Feb-1985 | 7.2 | |

| Mar-1985 | 7.2 | |

| Apr-1985 | 7.3 | 6.02 |

| May-1985 | 7.2 | |

| Jun-1985 | 7.4 | |

| Jul-1985 | 7.4 | 6.02 |

| Aug-1985 | 7.1 | |

| Sep-1985 | 7.1 | |

| Oct-1985 | 7.1 | 6.01 |

| Nov-1985 | 7.0 | |

| Dec-1985 | 7.0 | |

| Jan-1986 | 6.7 | 6.00 |

| Feb-1986 | 7.2 | |

| Mar-1986 | 7.2 | |

| Apr-1986 | 7.1 | 6.00 |

| May-1986 | 7.2 | |

| Jun-1986 | 7.2 | |

| Jul-1986 | 7.0 | 5.99 |

| Aug-1986 | 6.9 | |

| Sep-1986 | 7.0 | |

| Oct-1986 | 7.0 | 5.99 |

| Nov-1986 | 6.9 | |

| Dec-1986 | 6.6 | |

| Jan-1987 | 6.6 | 5.98 |

| Feb-1987 | 6.6 | |

| Mar-1987 | 6.6 | |

| Apr-1987 | 6.3 | 5.97 |

| May-1987 | 6.3 | |

| Jun-1987 | 6.2 | |

| Jul-1987 | 6.1 | 5.97 |

| Aug-1987 | 6.0 | |

| Sep-1987 | 5.9 | |

| Oct-1987 | 6.0 | 5.96 |

| Nov-1987 | 5.8 | |

| Dec-1987 | 5.7 | |

| Jan-1988 | 5.7 | 5.95 |

| Feb-1988 | 5.7 | |

| Mar-1988 | 5.7 | |

| Apr-1988 | 5.4 | 5.94 |

| May-1988 | 5.6 | |

| Jun-1988 | 5.4 | |

| Jul-1988 | 5.4 | 5.93 |

| Aug-1988 | 5.6 | |

| Sep-1988 | 5.4 | |

| Oct-1988 | 5.4 | 5.92 |

| Nov-1988 | 5.3 | |

| Dec-1988 | 5.3 | |

| Jan-1989 | 5.4 | 5.91 |

| Feb-1989 | 5.2 | |

| Mar-1989 | 5.0 | |

| Apr-1989 | 5.2 | 5.91 |

| May-1989 | 5.2 | |

| Jun-1989 | 5.3 | |

| Jul-1989 | 5.2 | 5.90 |

| Aug-1989 | 5.2 | |

| Sep-1989 | 5.3 | |

| Oct-1989 | 5.3 | 5.89 |

| Nov-1989 | 5.4 | |

| Dec-1989 | 5.4 | |

| Jan-1990 | 5.4 | 5.89 |

| Feb-1990 | 5.3 | |

| Mar-1990 | 5.2 | |

| Apr-1990 | 5.4 | 5.87 |

| May-1990 | 5.4 | |

| Jun-1990 | 5.2 | |

| Jul-1990 | 5.5 | 5.86 |

| Aug-1990 | 5.7 | |

| Sep-1990 | 5.9 | |

| Oct-1990 | 5.9 | 5.84 |

| Nov-1990 | 6.2 | |

| Dec-1990 | 6.3 | |

| Jan-1991 | 6.4 | 5.82 |

| Feb-1991 | 6.6 | |

| Mar-1991 | 6.8 | |

| Apr-1991 | 6.7 | 5.79 |

| May-1991 | 6.9 | |

| Jun-1991 | 6.9 | |

| Jul-1991 | 6.8 | 5.77 |

| Aug-1991 | 6.9 | |

| Sep-1991 | 6.9 | |

| Oct-1991 | 7.0 | 5.74 |

| Nov-1991 | 7.0 | |

| Dec-1991 | 7.3 | |

| Jan-1992 | 7.3 | 5.71 |

| Feb-1992 | 7.4 | |

| Mar-1992 | 7.4 | |

| Apr-1992 | 7.4 | 5.68 |

| May-1992 | 7.6 | |

| Jun-1992 | 7.8 | |

| Jul-1992 | 7.7 | 5.65 |

| Aug-1992 | 7.6 | |

| Sep-1992 | 7.6 | |

| Oct-1992 | 7.3 | 5.61 |

| Nov-1992 | 7.4 | |

| Dec-1992 | 7.4 | |

| Jan-1993 | 7.3 | 5.58 |

| Feb-1993 | 7.1 | |

| Mar-1993 | 7.0 | |

| Apr-1993 | 7.1 | 5.54 |

| May-1993 | 7.1 | |

| Jun-1993 | 7.0 | |

| Jul-1993 | 6.9 | 5.51 |

| Aug-1993 | 6.8 | |

| Sep-1993 | 6.7 | |

| Oct-1993 | 6.8 | 5.48 |

| Nov-1993 | 6.6 | |

| Dec-1993 | 6.5 | |

| Jan-1994 | 6.6 | 5.44 |

| Feb-1994 | 6.6 | |

| Mar-1994 | 6.5 | |

| Apr-1994 | 6.4 | 5.41 |

| May-1994 | 6.1 | |

| Jun-1994 | 6.1 | |

| Jul-1994 | 6.1 | 5.38 |

| Aug-1994 | 6.0 | |

| Sep-1994 | 5.9 | |

| Oct-1994 | 5.8 | 5.35 |

| Nov-1994 | 5.6 | |

| Dec-1994 | 5.5 | |

| Jan-1995 | 5.6 | 5.33 |

| Feb-1995 | 5.4 | |

| Mar-1995 | 5.4 | |

| Apr-1995 | 5.8 | 5.30 |

| May-1995 | 5.6 | |

| Jun-1995 | 5.6 | |

| Jul-1995 | 5.7 | 5.28 |

| Aug-1995 | 5.7 | |

| Sep-1995 | 5.6 | |

| Oct-1995 | 5.5 | 5.25 |

| Nov-1995 | 5.6 | |

| Dec-1995 | 5.6 | |

| Jan-1996 | 5.6 | 5.23 |

| Feb-1996 | 5.5 | |

| Mar-1996 | 5.5 | |

| Apr-1996 | 5.6 | 5.21 |

| May-1996 | 5.6 | |

| Jun-1996 | 5.3 | |

| Jul-1996 | 5.5 | 5.19 |

| Aug-1996 | 5.1 | |

| Sep-1996 | 5.2 | |

| Oct-1996 | 5.2 | 5.17 |

| Nov-1996 | 5.4 | |

| Dec-1996 | 5.4 | |

| Jan-1997 | 5.3 | 5.15 |

| Feb-1997 | 5.2 | |

| Mar-1997 | 5.2 | |

| Apr-1997 | 5.1 | 5.13 |

| May-1997 | 4.9 | |

| Jun-1997 | 5.0 | |

| Jul-1997 | 4.9 | 5.12 |

| Aug-1997 | 4.8 | |

| Sep-1997 | 4.9 | |

| Oct-1997 | 4.7 | 5.10 |

| Nov-1997 | 4.6 | |

| Dec-1997 | 4.7 | |

| Jan-1998 | 4.6 | 5.09 |

| Feb-1998 | 4.6 | |

| Mar-1998 | 4.7 | |

| Apr-1998 | 4.3 | 5.07 |

| May-1998 | 4.4 | |

| Jun-1998 | 4.5 | |

| Jul-1998 | 4.5 | 5.06 |

| Aug-1998 | 4.5 | |

| Sep-1998 | 4.6 | |

| Oct-1998 | 4.5 | 5.05 |

| Nov-1998 | 4.4 | |

| Dec-1998 | 4.4 | |

| Jan-1999 | 4.3 | 5.04 |

| Feb-1999 | 4.4 | |

| Mar-1999 | 4.2 | |

| Apr-1999 | 4.3 | 5.03 |

| May-1999 | 4.2 | |

| Jun-1999 | 4.3 | |

| Jul-1999 | 4.3 | 5.03 |

| Aug-1999 | 4.2 | |

| Sep-1999 | 4.2 | |

| Oct-1999 | 4.1 | 5.02 |

| Nov-1999 | 4.1 | |

| Dec-1999 | 4.0 | |

| Jan-2000 | 4.0 | 5.01 |

| Feb-2000 | 4.1 | |

| Mar-2000 | 4.0 | |

| Apr-2000 | 3.8 | 5.01 |

| May-2000 | 4.0 | |

| Jun-2000 | 4.0 | |

| Jul-2000 | 4.0 | 5.01 |

| Aug-2000 | 4.1 | |

| Sep-2000 | 3.9 | |

| Oct-2000 | 3.9 | 5.00 |

| Nov-2000 | 3.9 | |

| Dec-2000 | 3.9 | |

| Jan-2001 | 4.2 | 5.00 |

| Feb-2001 | 4.2 | |

| Mar-2001 | 4.3 | |

| Apr-2001 | 4.4 | 5.00 |

| May-2001 | 4.3 | |

| Jun-2001 | 4.5 | |

| Jul-2001 | 4.6 | 5.00 |

| Aug-2001 | 4.9 | |

| Sep-2001 | 5.0 | |

| Oct-2001 | 5.3 | 5.00 |

| Nov-2001 | 5.5 | |

| Dec-2001 | 5.7 | |

| Jan-2002 | 5.7 | 5.00 |

| Feb-2002 | 5.7 | |

| Mar-2002 | 5.7 | |

| Apr-2002 | 5.9 | 5.00 |

| May-2002 | 5.8 | |

| Jun-2002 | 5.8 | |

| Jul-2002 | 5.8 | 5.00 |

| Aug-2002 | 5.7 | |

| Sep-2002 | 5.7 | |

| Oct-2002 | 5.7 | 5.00 |

| Nov-2002 | 5.9 | |

| Dec-2002 | 6.0 | |

| Jan-2003 | 5.8 | 5.00 |

| Feb-2003 | 5.9 | |

| Mar-2003 | 5.9 | |

| Apr-2003 | 6.0 | 5.00 |

| May-2003 | 6.1 | |

| Jun-2003 | 6.3 | |

| Jul-2003 | 6.2 | 5.00 |

| Aug-2003 | 6.1 | |

| Sep-2003 | 6.1 | |

| Oct-2003 | 6.0 | 5.00 |

| Nov-2003 | 5.8 | |

| Dec-2003 | 5.7 | |

| Jan-2004 | 5.7 | 5.00 |

| Feb-2004 | 5.6 | |

| Mar-2004 | 5.8 | |

| Apr-2004 | 5.6 | 5.00 |

| May-2004 | 5.6 | |

| Jun-2004 | 5.6 | |

| Jul-2004 | 5.5 | 5.00 |

| Aug-2004 | 5.4 | |

| Sep-2004 | 5.4 | |

| Oct-2004 | 5.5 | 5.00 |

| Nov-2004 | 5.4 | |

| Dec-2004 | 5.4 | |

| Jan-2005 | 5.3 | 5.00 |

| Feb-2005 | 5.4 | |

| Mar-2005 | 5.2 | |

| Apr-2005 | 5.2 | 5.00 |

| May-2005 | 5.1 | |

| Jun-2005 | 5.0 | |

| Jul-2005 | 5.0 | 5.00 |

| Aug-2005 | 4.9 | |

| Sep-2005 | 5.0 | |

| Oct-2005 | 5.0 | 4.98 |

| Nov-2005 | 5.0 | |

| Dec-2005 | 4.9 | |

| Jan-2006 | 4.7 | 4.97 |

| Feb-2006 | 4.8 | |

| Mar-2006 | 4.7 | |

| Apr-2006 | 4.7 | 4.97 |

| May-2006 | 4.6 | |

| Jun-2006 | 4.6 | |

| Jul-2006 | 4.7 | 4.96 |

| Aug-2006 | 4.7 | |

| Sep-2006 | 4.5 | |

| Oct-2006 | 4.4 | 4.95 |

| Nov-2006 | 4.5 | |

| Dec-2006 | 4.4 | |

| Jan-2007 | 4.6 | 4.95 |

| Feb-2007 | 4.5 | |

| Mar-2007 | 4.4 | |

| Apr-2007 | 4.5 | 4.94 |

| May-2007 | 4.4 | |

| Jun-2007 | 4.6 | |

| Jul-2007 | 4.7 | 4.94 |

| Aug-2007 | 4.6 | |

| Sep-2007 | 4.7 | |

| Oct-2007 | 4.7 | 4.93 |

| Nov-2007 | 4.7 | |

| Dec-2007 | 5.0 | |

| Jan-2008 | 5.0 | 4.93 |

| Feb-2008 | 4.9 | |

| Mar-2008 | 5.1 | |

| Apr-2008 | 5.0 | 4.93 |

| May-2008 | 5.4 | |

| Jun-2008 | 5.6 | |

| Jul-2008 | 5.8 | 4.92 |

| Aug-2008 | 6.1 | |

| Sep-2008 | 6.1 | |

| Oct-2008 | 6.5 | 4.92 |

| Nov-2008 | 6.8 | |

| Dec-2008 | 7.3 | |

| Jan-2009 | 7.8 | 4.92 |

| Feb-2009 | 8.3 | |

| Mar-2009 | 8.7 | |

| Apr-2009 | 9.0 | 4.97 |

| May-2009 | 9.4 | |

| Jun-2009 | 9.5 | |

| Jul-2009 | 9.5 | 5.00 |

| Aug-2009 | 9.6 | |

| Sep-2009 | 9.8 | |

| Oct-2009 | 10.0 | 5.02 |

| Nov-2009 | 9.9 | |

| Dec-2009 | 9.9 | |

| Jan-2010 | 9.8 | 5.06 |

| Feb-2010 | 9.8 | |

| Mar-2010 | 9.9 | |

| Apr-2010 | 9.9 | 5.08 |

| May-2010 | 9.6 | |

| Jun-2010 | 9.4 | |

| Jul-2010 | 9.4 | 5.10 |

| Aug-2010 | 9.5 | |

| Sep-2010 | 9.5 | |

| Oct-2010 | 9.4 | 5.11 |

| Nov-2010 | 9.8 | |

| Dec-2010 | 9.3 | |

| Jan-2011 | 9.1 | 5.13 |

| Feb-2011 | 9.0 | |

| Mar-2011 | 9.0 | |

| Apr-2011 | 9.1 | 5.14 |

| May-2011 | 9.0 | |

| Jun-2011 | 9.1 | |

| Jul-2011 | 9.0 | 5.15 |

| Aug-2011 | 9.0 | |

| Sep-2011 | 9.0 | |

| Oct-2011 | 8.8 | 5.15 |

| Nov-2011 | 8.6 | |

| Dec-2011 | 8.5 | |

| Jan-2012 | 8.3 | 5.13 |

| Feb-2012 | 8.3 | |

| Mar-2012 | 8.2 | |

| Apr-2012 | 8.2 | 5.12 |

| May-2012 | 8.2 | |

| Jun-2012 | 8.2 | |

| Jul-2012 | 8.2 | 5.10 |

| Aug-2012 | 8.1 | |

| Sep-2012 | 7.8 | |

| Oct-2012 | 7.8 | 5.07 |

| Nov-2012 | 7.7 | |

| Dec-2012 | 7.9 | |

| Jan-2013 | 8.0 | 5.05 |

| Feb-2013 | 7.7 | |

| Mar-2013 | 7.5 | |

| Apr-2013 | 7.6 | 5.03 |

| May-2013 | 7.5 | |

| Jun-2013 | 7.5 | |

| Jul-2013 | 7.3 | 5.00 |

| Aug-2013 | 7.2 | |

| Sep-2013 | 7.2 | |

| Oct-2013 | 7.2 | 4.98 |

| Nov-2013 | 6.9 | |

| Dec-2013 | 6.7 | |

| Jan-2014 | 6.6 | 4.95 |

| Feb-2014 | 6.7 | |

| Mar-2014 | 6.7 | |

| Apr-2014 | 6.3 | 4.93 |

| May-2014 | 6.3 | |

| Jun-2014 | 6.1 | |

| Jul-2014 | 6.2 | 4.92 |

| Aug-2014 | 6.2 | |

| Sep-2014 | 5.9 | |

| Oct-2014 | 5.7 | 4.88 |

| Nov-2014 | 5.8 | |

| Dec-2014 | 5.6 | |

| Jan-2015 | 5.7 | 4.83 |

| Feb-2015 | 5.5 | |

| Mar-2015 | 5.5 | |

| Apr-2015 | 5.4 | 4.79 |

| May-2015 | 5.5 | |

| Jun-2015 | 5.3 | |

| Jul-2015 | 5.2 | 4.77 |

| Aug-2015 | 5.1 | |

| Sep-2015 | 5.0 | |

| Oct-2015 | 5.0 | 4.76 |

| Nov-2015 | 5.0 | |

| Dec-2015 | 5.0 | |

| Jan-2016 | 4.9 | 4.75 |

| Feb-2016 | 4.9 | |

| Mar-2016 | 5.0 | |

| Apr-2016 | 5.0 | 4.75 |

| May-2016 | 4.7 | |

| Jun-2016 | 4.9 | |

| Jul-2016 | 4.9 | 4.74 |

| Aug-2016 | 4.9 | |

| Sep-2016 | 5.0 | |

| Oct-2016 | 4.9 | 4.74 |

| Nov-2016 | 4.6 | |

| Dec-2016 | 4.7 | |

| Jan-2017 | 4.8 | 4.74 |

| Feb-2017 | 4.7 | |

| Mar-2017 | 4.5 | |

| Apr-2017 | 4.4 | 4.74 |

| May-2017 | 4.3 | |

| Jun-2017 | 4.3 | |

| Jul-2017 | 4.3 | 4.74 |

| Aug-2017 | 4.4 | |

| Sep-2017 | 4.2 | |

| Oct-2017 | 4.1 | 4.74 |

| Nov-2017 | 4.1 | |

| Dec-2017 | 4.1 | |

| Jan-2018 | 4.1 | 4.73 |

| Feb-2018 | 4.1 | |

| Mar-2018 | 4.1 |

Note: NAIRU refers to the nonaccelerating inflation rate of unemployment (another term for the natural rate of unemployment).

Source: Data on the natural rate of unemployment come from the Congressional Budget Office, “Online Data on Potential Output and Its Underlying Inputs," 2018; data on actual unemployment rate come from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Series ID: LNS14000000. (Seas) Unemployment Rate,” accessed August 2018. Shaded areas represent recessions.

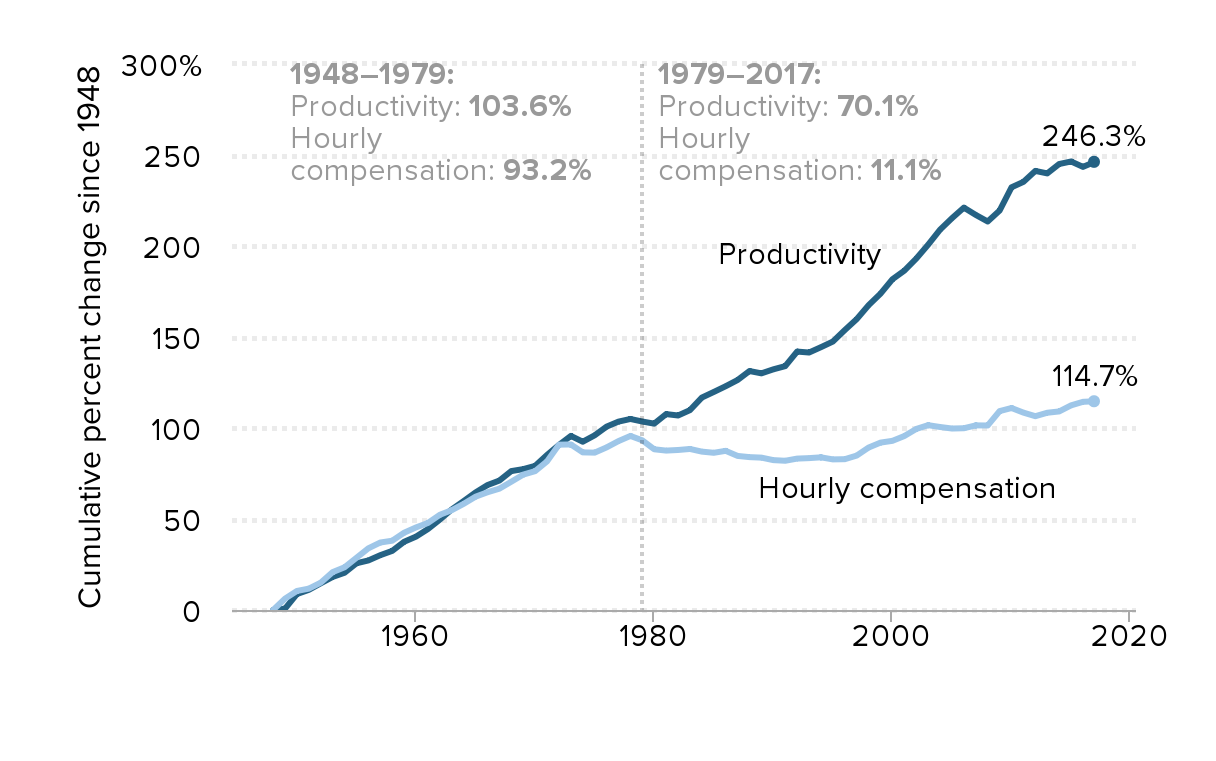

This clear shift in the Fed’s monetary policy framework to a more heavy weighting of the inflation mandate coincides strikingly with the post-1979 slowdown in wage growth for the large majority of American workers. Figure B shows the relationship between a typical worker’s compensation per hour worked and economywide productivity (a measure of total income generated in the economy in an average hour of work). Between 1949 and the mid-1970s, these measures rose in lockstep. Since 1979, rising inequality has driven these two measures decisively apart.

The gap between productivity and a typical worker's compensation has increased dramatically since 1979: Productivity growth and hourly compensation growth, 1948–2017

| Year | Hourly compensation | Net productivity |

|---|---|---|

| 1948 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| 1949 | 6.24% | 0.74% |

| 1950 | 10.46% | 8.77% |

| 1951 | 11.74% | 11.07% |

| 1952 | 15.02% | 14.66% |

| 1953 | 20.82% | 18.17% |

| 1954 | 23.48% | 20.47% |

| 1955 | 28.69% | 25.67% |

| 1956 | 33.89% | 27.23% |

| 1957 | 37.08% | 30.12% |

| 1958 | 38.07% | 32.48% |

| 1959 | 42.46% | 37.48% |

| 1960 | 45.37% | 40.32% |

| 1961 | 47.83% | 44.49% |

| 1962 | 52.31% | 49.66% |

| 1963 | 54.85% | 55.26% |

| 1964 | 58.32% | 59.85% |

| 1965 | 62.26% | 64.60% |

| 1966 | 64.69% | 68.64% |

| 1967 | 66.67% | 71.12% |

| 1968 | 70.48% | 76.33% |

| 1969 | 74.39% | 77.41% |

| 1970 | 76.29% | 79.19% |

| 1971 | 81.65% | 85.19% |

| 1972 | 90.84% | 90.68% |

| 1973 | 90.95% | 95.65% |

| 1974 | 86.61% | 92.46% |

| 1975 | 86.46% | 95.98% |

| 1976 | 89.34% | 100.75% |

| 1977 | 92.81% | 103.51% |

| 1978 | 95.64% | 104.96% |

| 1979 | 93.23% | 103.56% |

| 1980 | 88.31% | 102.39% |

| 1981 | 87.59% | 107.64% |

| 1982 | 87.92% | 106.87% |

| 1983 | 88.48% | 109.81% |

| 1984 | 87.02% | 116.72% |

| 1985 | 86.38% | 119.80% |

| 1986 | 87.45% | 122.96% |

| 1987 | 84.66% | 126.36% |

| 1988 | 84.00% | 131.30% |

| 1989 | 83.72% | 130.03% |

| 1990 | 82.35% | 132.23% |

| 1991 | 82.00% | 133.99% |

| 1992 | 83.19% | 141.99% |

| 1993 | 83.45% | 141.47% |

| 1994 | 83.88% | 144.41% |

| 1995 | 82.75% | 147.50% |

| 1996 | 82.86% | 153.80% |

| 1997 | 84.85% | 159.82% |

| 1998 | 89.26% | 167.48% |

| 1999 | 91.97% | 173.81% |

| 2000 | 92.94% | 181.72% |

| 2001 | 95.59% | 186.46% |

| 2002 | 99.48% | 193.07% |

| 2003 | 101.56% | 200.72% |

| 2004 | 100.55% | 208.97% |

| 2005 | 99.71% | 215.29% |

| 2006 | 99.87% | 221.08% |

| 2007 | 101.44% | 217.07% |

| 2008 | 101.38% | 213.46% |

| 2009 | 109.28% | 219.48% |

| 2010 | 110.98% | 232.25% |

| 2011 | 108.45% | 235.24% |

| 2012 | 106.49% | 241.25% |

| 2013 | 108.38% | 239.89% |

| 2014 | 109.10% | 245.04% |

| 2015 | 112.44% | 246.44% |

| 2016 | 114.38% | 243.47% |

| 2017 | 114.70% | 246.25% |

Notes: Data are for compensation (wages and benefits) of production/nonsupervisory workers in the private sector and net productivity of the total economy. “Net productivity” is the growth of output of goods and services less depreciation per hour worked.

Source: EPI analysis of unpublished Total Economy Productivity data from Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Labor Productivity and Costs program, wage data from the BLS Current Employment Statistics, BLS Employment Cost Trends, BLS Consumer Price Index, and Bureau of Economic Analysis National Income and Product Accounts.

The relationship between these two shifts—toward a monetary policy framework more tolerant of high unemployment and toward a labor market that does not generate much wage growth for the vast majority—is confirmed in more detailed statistical tests of correlations between unemployment and wage growth. These tests show that lower unemployment boosts wage growth more for low- and moderate-wage workers than it does for higher-wage workers. To put it simply, low- and middle-wage workers need the leverage and bargaining power that accompanies tighter labor markets more than high-wage workers do. This is especially true in the post-1979 period, as institutional bulwarks of bargaining power for these workers—like unions, high federal minimum wages, and relatively low levels of imports from low-wage nations— were all intentionally eroded by policymakers.

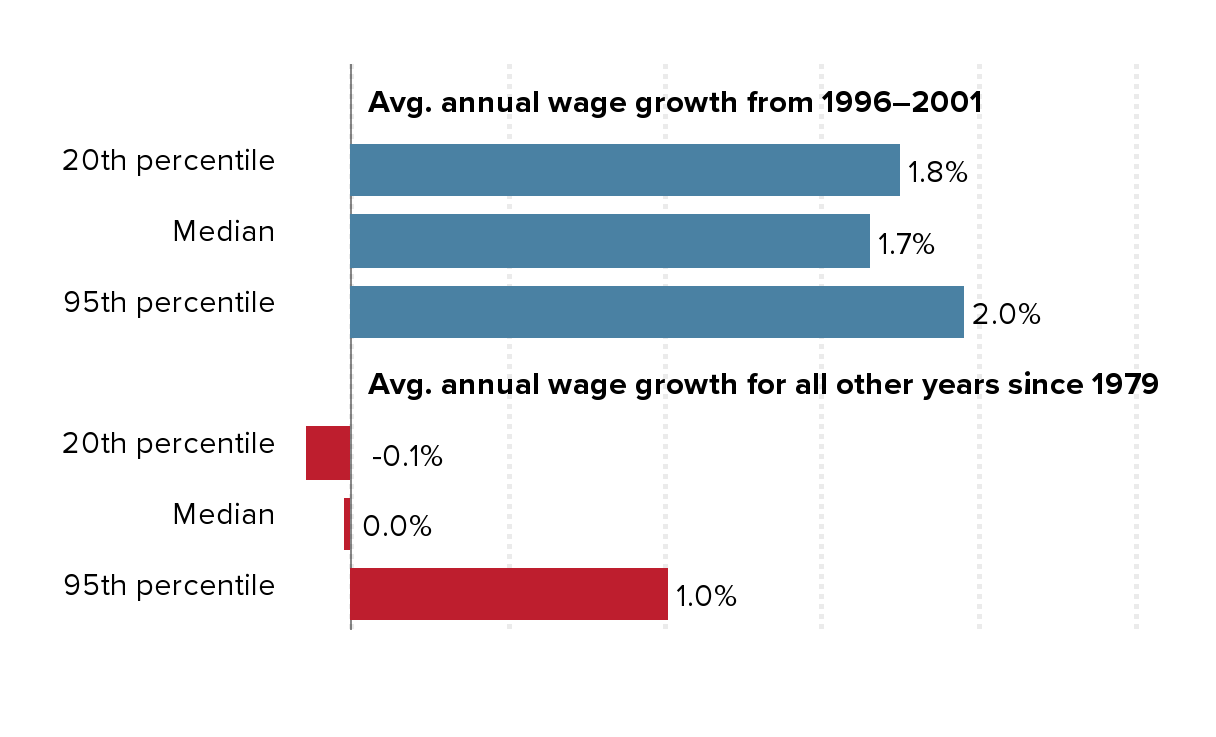

Encouragingly, there is good evidence that tight labor markets can temporarily offset much of the decline in these structural determinants of wage growth. In the late 1990s the Fed admirably allowed unemployment to fall well beneath real-time estimates of the natural rate. The result was not inflation, but the first sustained period of across-the-board wage growth in a generation. Figure C shows average annual wage growth of workers at the 20th, 50th, and 95th percentiles of the wage distribution for two periods: 1996–2001 (the period of tight labor markets) and every other post-1979 year. It shows that essentially all wage growth that happened after 1979 for low- and middle-wage workers happened in the five-year burst when labor markets were tight.

The Fed can look to the late 1990s for guidance on how to raise wages: Average annual wage growth from 1996–2001 vs. all other years between 1979 and 2017

| Wage percentile | Avg. annual wage growth |

|---|---|

| 0% | |

| 20th percentile | 1.75% |

| Median | 1.66% |

| 95th percentile | 1.96% |

| 0% | |

| 20th percentile | -0.15% |

| Median | -0.02% |

| 95th percentile | 1.01% |

Source: Adapted from Figure C in Josh Bivens and Ben Zipperer, The Importance of Locking in Full Employment for the Long Haul, Economic Policy Institute, July 2018. Wage growth is inflation-adjusted.

How different would the world have been if the Fed allowed substantially tighter labor markets post-1979?

In a recent-ish paper, Ben Zipperer and I found that each 1 percentage-point drop in the unemployment rate was associated with annualized wage growth for low- and middle-wage workers that was faster by 0.6 and 0.5 percent, respectively. We noted before that actual unemployment was cumulatively 15 percentage points above the estimated “natural rate” between 1979 and 2007. Thus, a very rough estimate is that wages for these low- and middle-wage workers could have been 9.0 percent and 7.5 percent higher (respectively) in 2007, but for the effect of excess unemployment (multiplying 15 percentage points of excess unemployment by the coefficients of 0.6 and 0.5). This would have resulted in wage growth from 1979 to 2007 that was 75 percent faster than what workers at the 50 percentile experienced. Workers at the 10th percentile saw outright declines in wages between these years—tighter labor markets could have swung their cumulative wage growth from -4 percent to (positive) 5 percent. If wages at the top of the distribution were not affected by tighter labor markets (often coefficients on wage growth for high-end workers are right on the edge of statistical significance), this would imply that roughly 30–40 percent of the rise in inequality in wages that occurred between 1979 and 2007 could have been avoided (if inequality is proxied by the ratio of wages at the 95th percentile to wages at the 10th and 50th percentiles).

Additionally, a previous newsletter noted that tight labor markets also lead to a redistribution away from capital income and toward labor income overall, a shift that also would have allowed faster wage growth for most workers.

Of course, these are crude estimate with lots of caveats. The most important one is that perhaps inflation would’ve been higher and/or accelerated, making the tighter labor markets impossible to sustain. But there is ample evidence that the Fed didn’t just engineer stable inflation by keeping labor markets intentionally soft in those years; it overshot and saw steadily declining inflation rates. One objection to these estimates might be that it’s unrealistic for the Fed to have managed to hit the natural rate target on average over this entire 28 year period. But this objection would be wrong. For one, the Fed did manage to hit the natural rate (or even undershoot it) over the previous 30 years. For another, estimates of the natural rate should not be seen as hard floors below which unemployment can never be allowed to reach. Instead, extended periods when actual unemployment exceeds the natural rate should be matched by equally extended periods when actual unemployment dips below the natural rate.

What does this mean for the reassessment of the monetary policy framework?

The lessons of this history for the monetary policy framework are clear: the Fed should certainly try to maximize its effectiveness in fighting recessions, but its real opportunity for helping low- and middle-wage workers lies in being slower in raising interest rates to restrain expansions that are already underway.

The Fed and other central banks have often viewed their main job as “taking away the punch bowl just as the party gets going,” meaning that they think they have to restrain expansions and stop downward movement in unemployment before an overheating economy sparks inflation. Modern economies do need policymakers to keep an eye on inflation, but central bank orthodoxy before the Great Recession had swung way too far towards sacrificing large and progressive benefits of genuine full employment on the altar of inflation control.

The most important change the Fed could make in its monetary policy framework may just be a simple commitment to wait until inflation durably exceeds the Fed’s target in the data before it begins raising interest rates. Currently, the Fed and other central bankers worry about being behind the curve in containing inflation, and hence raise rates in expectation of future accelerations of inflation. The benefits of this kind of excess vigilance in fighting forecast inflation are utterly swamped by the potential benefits that would accrue to low- and middle-wage workers if tight labor markets were allowed to persist and inflation did not turn up. This is absolutely a low-stakes, high-return risk the Fed should commit to taking on as it reassesses its policy framework.

Enjoyed this post?

Sign up for EPI's newsletter so you never miss our research and insights on ways to make the economy work better for everyone.