Paul Ryan is not (and has never been) a deficit hawk

Republican vice presidential nominee Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) is not a deficit hawk, and has never been a deficit hawk. In the near-term, advocating accelerated deficit reduction is economically detrimental rather than praiseworthy, but in many circles the “deficit hawk” label is bestowed as a compliment upon Ryan for supposedly stabilizing the long-term fiscal outlook. Ryan is hawkishly anti-government spending, except for defense spending, and he falsely conflates domestic spending with deficits and public debt. But Ryan’s purported concern about the deficit is belied by his proposed $4.5 trillion in unfunded tax cuts and reliance on made-up revenue levels to pad long-term budget projections from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). This isn’t a secret to budget analysts and economists (e.g., Peter Orszag’s recent piece in the Washington Post), but it regrettably continues to be lost on much of the press and punditry.

Take, for instance, last week’s Leader in The Economist, Paul Ryan: The man with the plan, which praised Ryan as “the first politician to produce a plausible plan for closing the deficit, which he did in April last year.” This is an egregious misrepresentation of fact. Ryan’s fiscal year 2012 budget would not have reached balance until somewhere between 2030 and 2040, according to CBO’s long-term analysis, but even this “feat” was falsely predicated on revenue magically rising to 19 percent of GDP—as Ryan demanded CBO assume. Read more

Key goals of 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom are still unmet

Today is the 49th anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King’s brilliant “I Have a Dream” speech, the final speech of the 1963 March on Washington, which was officially titled the “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.” That event is obscured by the distance of a half-century, but it’s worth the effort to review the official demands of the march and the economic thinking of King and his allies, A. Philip Randolph of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Walter Reuther of the United Auto Workers. What they wanted for Americans then is still badly needed today—perhaps more than ever.

The March was about civil rights, voting rights and racial equality, but it was also about the need for jobs and for jobs that paid a decent wage. The marchers wanted the federal minimum wage raised nearly 75 percent, from $1.15 an hour to $2.00 an hour. They also called for “A massive federal program to train and place all unemployed workers—Negro and white—on meaningful and dignified jobs at decent wages.”

In 1963, the unemployment rate averaged about 5.0 percent, which looks good compared to today’s 8.3 percent, but King and the other organizers wanted full employment and believed it was the federal government’s responsibility to provide it. Read more

Health reform and the $716 billion lie

The Affordable Care Act (ACA), called “Obamacare” by opponents and supporters alike, has been maligned and misrepresented countless times over the last few years. The most recent claim—which has turned up in a recent Mitt Romney ad but has been a staple of GOP talking points since the Paul Ryan pick for vice president—is, “You paid into Medicare for years … but now when you need it, Obama has cut $716 billion from Medicare … to pay for Obamacare.” In other words, ACA took money out of the Medicare system for use elsewhere.

This is a pretty big lie. To take money “out of the Medicare system,” one would have to actually divert revenues away from the program. But ACA doesn’t do this at all—instead, it reduces how much Medicare will have to spend over the next 10 years by $716 billion. It does this without actually cutting benefits, instead deriving savings from three areas:

- Reducing reimbursements Medicare currently makes to hospitals—but by less than the gain hospitals would receive from newly-insured patients purchasing hospital services in coming decades.

- Reforming the separate Medicare Advantage program, which was supposed to save money, but ended up being more expensive. Read more

Apple in China: Failing to make good on its commitment?

Apple’s key Chinese supplier is Foxconn, made famous by the rash of suicides committed by its employees, who live packed into dorms, far from home, working brutal schedules of overtime (sometimes as much as 80 hours a month, on top of the core 160 hours), subjected to verbal abuse and humiliating punishment by supervisors, and systematically cheated on wages.

When labor rights groups in China and Hong Kong exposed these conditions and the New York Times published a front-page exposé, Apple hired the Fair Labor Association (FLA) to help it improve conditions—and its corporate image. In a public report, Apple committed itself to a broad range of reforms, and has made some headway on several fronts, according to the FLA.

But many observers are skeptical because Apple and Foxconn have put off most of the reforms that would actually cost them some money. The FLA could not, for example, get the companies to agree to comply with Chinese law limiting maximum overtime hours until the summer of 2013, and the companies continue to subject Foxconn workers to 60 hours of overtime per month—nearly twice the amount of overtime permitted by law. The companies also pledged only to study whether the workers were right in their complaints that wages are too low to meet basic needs. And most telling, there is no indication the companies have kept their public promise to pay back wages to the hundreds of thousands of employees Foxconn systematically cheated by working them “off the clock.” Read more

Bad economics leads to bad H-2B guest worker legislation

Louisiana politicians have been getting bad advice from their state’s economists about the Department of Labor’s guest worker regulations. Rep. Rodney Alexander (R-La.) posted a story on his website about the supposedly enormous negative impact of a new Department of Labor regulation that would raise the wages of U.S. and foreign workers employed by companies that import H-2B guest workers. Alexander and Sen. Mary Landrieu (D-La.) both voted to block the new wage rule from taking effect.

The outsized impact estimates come from a March 23, 2012 report by three Louisiana State University economists, entitled Economic Impact on Louisiana Agricultural Industries of the Proposed Change to the Wage Methodology for the Temporary Non-Agricultural Employment H-2B Program. A careful look at the report shows that the estimates are certainly wrong.

The report’s authors, Kurt M. Guidry, J. Matthew Fannin, and Michael E. Salassi, assume that if wages increase, net income (sales revenue minus wages) will simply decrease proportionately. Rather than increase prices and pass them along to consumers, or mechanize certain operations to reduce the wage bill, or improve productivity through better hiring, training, or management, seafood companies and landscaping contractors will lose $1 of income for each $1 of higher wages. That is an unreasonable assumption, which the report applies to about a dozen different industries, from agricultural aviation and forestry to hotels and food service. Read more

MAPI report on regulation is latest example of business-sponsored junk science

Republicans in Congress have been engaged in a two-year long assault on the government’s regulatory powers, attacking everything from the Clean Air Act and mercury pollution controls to the National Labor Relations Board’s enforcement powers. Their actions have been directed by business groups like the Chamber of Commerce, which publish seemingly-credible reports with big numbers about regulation’s supposed negative impact on the economy, relentlessly shifting blame away from themselves for the failure of wealthy corporations to create jobs in the United States instead of in China, Mexico and Bangladesh.

The latest installment in this wave of faux reports comes from the Manufacturers Alliance for Productivity and Innovation. Yesterday, they released a commissioned report on the costs of regulation that was so slanted and sloppy it seems like a parody. The authors throw out a bunch of big numbers with no supporting data and then—“extrapolating”—pretend that they can reasonably estimate how much regulations have reduced manufacturing activity. But the fact, of course, is that manufacturing employment has risen over the last two years—for the first time in a decade—just when the supposed cumulative impact of regulations should have been taking its biggest toll.

The authors acknowledge that they made no attempt to estimate the benefits of regulation, either to the public in general, workers, consumers, or the industries themselves. Read more

What do Social Security, Medicare and public investments have in common? They make us richer

Yesterday, David Brooks channeled a deeply flawed presentation by the Third Way to argue that while the federal government used to spend money on things that improved national “dynamism” it now just spends on “entitlements.”

A word of (very) muted praise for Brooks—he does lament that too much spending goes on tax loopholes, and he’s largely right there.

But, he spends most of his time, and, Third Way spends all their time, arguing that there is something deeply damaging about the fact that federal spending on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid is now a bigger part of the budget than public investments. There’s little economic basis for this angst.

You’d have to look hard to find a bigger fan of public investments than me. But, the economic benefits of Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are absolutely enormous. They provide a service (insurance against risk, and people value insurance quite highly) much more efficiently than do private-sector providers. Read more

What does health care have to do with the wage slowdown? Not much

David Leonhardt on the New York Times‘ Economix blog is spurring an interesting conversation about what has caused the slowdown in income growth. Though not explicit, what Leonhardt is asking people to explain is the sluggish growth in median household income since 2000, when incomes for working-age households fell over the 2000–2007 business cycle (the first time in any cycle in the post-war period) and then were battered by the great recession we’re still effectively in. This is what we are referring to in the forthcoming The State of Working America (out on Sept. 11) as the “lost decade.”

The heart of the matter is the ongoing failure of wages and benefits for typical workers (including those with a college degree!) to see any improvements, even though productivity (the ability of the economy to provide higher pay) has grown appreciably. I want to focus on one issue raised in this discussion, the role of rising health care costs on wage growth, an issue we examine (in the new book) more thoroughly than I have seen before. The issue is the extent to which rising employer health care costs have squeezed wage growth and contributed to rising wage inequality. An earlier paper tackled this issue as well.

The relationship between employer health insurance costs and wages is that employers set the growth of compensation, and when health costs rise, there is simply less compensation available for wage growth. This assumes that higher health spending by employers offsets the possibility of higher wages dollar-for-dollar. (Although this is likely not the case, I will assume it for our purpose here; there is also the issue that there are other benefits beyond health that could provide an alternative to wages in soaking up increased health costs.)

The potential squeeze of health care on wages can be measured simply by examining employer health care costs as a share of total wages; the faster that share grows, the more there is a squeeze on wages. Read more

Segregation, the black-white achievement gap, and the Romneys

We cannot remedy the large racial achievement gaps in American education if we continue to close our eyes to the continued racial segregation of schools, owing primarily to the continued segregation of our neighborhoods. We pretend that this segregation is nobody’s fault in particular (we call it “de facto” segregation), and that therefore there is nothing we can or should do about it. Instead, we think that somehow we can devise reform programs that will create separate but equal education. One after another of these programs has failed—more teacher accountability and charter schools being only the latest—but we persist.

The presidential campaign can be a reminder, though, of the opportunities we’ve missed and continue to miss. Forty years ago, George Romney, Mitt’s father, resigned as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development after unsuccessfully attempting to force homogenous white middle-class suburbs to integrate by race. Secretary Romney withheld federal funds from suburbs that did not accept scatter-site public and subsidized low and moderate income housing and that did not repeal exclusionary zoning laws that prohibited multi-unit dwellings or modest single family homes—laws adopted with the barely disguised purpose of ensuring that suburbs would remain white and middle class.

Confronted at a press conference about his cabinet secretary’s actions, President Nixon undercut Romney, responding, “I believe that forced integration of the suburbs is not in the national interest.” This has since been unstated national policy and as a result, low-income African Americans remain concentrated in distressed urban neighborhoods and their children remain in what we mistakenly think are “failing schools.” Nationwide, African Americans remain residentially as isolated from whites as they were in 1950, and more isolated than in 1940. Read more

Bankrupt! No, not the U.S. economy, just the policy discussion about it

This Week with George Stephanopolous yesterday was dominated by a panel discussing the deeply silly question of, “Is the U.S. going bankrupt?”

It’s a silly question for one because it conflates issues with the federal budget deficit (which the show was entirely about) with the U.S. economy writ large. I know this is news to far too many pundits but the budget deficit and the U.S. economy are not the same thing. And if you look at the broader perspective of the U.S. economy, it’s clear that it’s not “going broke.” On average, the U.S. economy over any long period of time has been (and will be, absent some catastrophe) growing acceptably fast. Unfortunately, very few American households have actually experienced this “average” growth, since incomes at the very top have grown extraordinarily rapidly and absorbed vastly disproportionate shares of income growth in recent decades. So, if This Week wants to devote a very serious show obsessing about the dangers of growing inequality, then I’ll be happy to give them a round of applause for devoting time to an actual, identifiable economic problem.

And even in its own poorly-defined terms (i.e., the outlook for the federal budget deficit), the show was mostly a bust.

For one, nobody reminded the panel or its viewers that the large increase in budget deficits in recent years have been driven entirely by the Great Recession (and its aftermath) and the explicitly temporary policy responses passed in its wake. This is important to know. In 2006 and 2007—even after the Bush tax cuts, wars fought with no dedicated funding and the passage of a deeply-inefficient Medicare drug program that also had no funding source—budget deficits averaged around 1.5 percent of total GDP, levels that no economist would argue are evidence of a crisis. Read more

In what way is a college degree valuable in a recession?

Dylan Matthews over at Wonkblog used some data we provided to point out “one big flaw” in a report (written by Anthony Carnevale and two co-authors for the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce (GCEW)) touting the value of a college education in the recession and recovery. The flaw is, “it doesn’t separate out people who only have a bachelor’s from the 11.3 percent of workers who have an advanced degree beyond a bachelor’s,” when it talks about “college graduates.” Matthews notes that:

“While those with only a BA still did much, much better than people with a high school degree or only some college, they still saw job stagnation during the recession. The only group that continued to gain jobs were those with advanced degrees. Fully 98.3 percent of job gains among those with at least a bachelor’s were realized by those with advanced degrees…”

I want to dig into the issues raised by the GCEW report and the general discussion of the value of a college degree. It is important to separate out two dimensions to the value of a college degree that are frequently conflated, as this report does. One issue is whether an individual will be relatively better off if he or she obtains a college degree and the second issue is the benefit to the economy of a greatly boosted share of the workforce with a college degree (say, if we had 40 or 50 percent rather than the current 33.2 percent with a college degree or further education).

I am totally in favor of policies which facilitate every person’s ability to obtain (and complete) a college degree or other advanced training or skills (i.e., apprenticeships, associate degrees). Those who do advance their education and skills will, on average, be better off in terms of their incomes, employment, health, and be more engaged citizens than those who have not been able to pursue greater education and skills. So, on issue number one there need not be any debate. More education and skills can also be essential for improving social mobility and opportunity and generating a more inclusive economy.

However, if the entire workforce had college educations, we still would have unemployment over 8 percentRead more

Paul Ryan on Social Security

As this week brings us both the announcement of Paul Ryan as Mitt Romney’s running mate and Social Security’s 77th birthday (today, August 14), it seems appropriate to focus our lens on Social Security from Ryan’s perspective.

Ryan has long championed the privatization of social insurance programs. His last two budget blueprints put forth in fiscal 2012 and 2013—both called The Path to Prosperity—would turn Medicare into a system of vouchers that individuals could use to buy private insurance. These vouchers would not keep pace with rising health care costs, forcing seniors to bear an increasingly greater burden of their health care costs in years to come.

Privatization of government programs seems to be a theme with Ryan. On Social Security, Ryan—a Social Security recipient himself as a young man—helped lay the groundwork for George W. Bush’s push to privatize Social Security, as described in a recent New Yorker profile of the congressman. Ryan worked with former Sen. John Sununu (R-NH) to create a plan which was centered on the creation of personal savings accounts. Under the plan, a portion of an individual’s payroll tax contribution would be diverted from the OASDI trust fund into an individual account, which would then be invested. Such a diversion of funds would have decreased Social Security’s revenue and required a transfer of funds from the rest of the budget to fund benefit obligations, as this Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis reported. In other words, the Ryan-Sununu plan to bring long-term solvency to Social Security would have required the federal government to borrow heavily to finance promised benefits.

We all know how the story ended: President Bush spent significant political capital promoting a somewhat more cautious version of this plan, going on a “Social Security Road Tour” that ultimately went nowhere. Ryan didn’t end his quest there, however.Read more

Lessons from the French: It’s time to tax high-frequency trading

France recently pushed ahead of the European Union in implementing a financial transactions tax (FTT). Championed by both France and Germany, the European Union has been moving toward an FTT for several years, albeit with strong resistance from the United Kingdom. The new French FTT is fairly narrow in its base: 0.2 percent on the sale of stock of publicly-traded French companies valued above €1 billion (most FTT proposals would apply varying rates to range of assets—stocks, bonds, options, futures, and swaps—to minimize tax distortions and arbitrage opportunities). What’s unusual about France’s move is their additional high-frequency trading (HFT) tax, targeting algorithmic computer trades executed within half a second, as detailed by Steven Rosenthal on TaxVox.

The timing of France’s HFT tax is quite apropos given Knight Capital Group’s near-fatal $440 million trading loss from a software glitch triggering a wave of unintended trades (a cash lifeline from outside investors kept the firm afloat while severely diluting existing shares). Citing computer errors marring Facebook’s NASDAQ IPO, the Associated Press observed this week that, “Problems such as the one Knight caused last week have been occurring more regularly as the stock market’s trading systems come under increasing pressure from traders using huge computer systems.”

Indeed, remember the 2010 flash crash? In a bizarre spectacle on May 6 of that year, the Dow Jones Industrial Average—already down 4 percent for the day—abruptly plunged another 5-6 percent in a matter of minutes, hitting a floor down 992.6 points (-9.1 percent) from opening, and then rapidly rebounded. By the ring of the closing bell, the Chicago Board of Option Exchange’s Volatility Index for the S&P 500—a prime gauge of market fear—had surged 31.7 percent from the previous day’s close, the sixth-largest volatility spike this tumultuous decade. The Securities and Exchange Commission and the Commodities Futures Trading Commission Read more

The State Department just created about 4,000 jobs in Alaska

For years, seafood processing companies in Alaska have been hiring foreign student guest workers on J-1 visas through the Summer Work Travel program (SWT). Despite the astronomical youth unemployment rate—averaging 15.3 percent last year for 16-24 year olds in Alaska, and 17.3 percent nationally—about 4,000 SWT workers were employed by these companies last year. Thanks to new regulations issued by the State Department in May, however, there’s good reason to believe that many of those jobs will go to young unemployed Alaskans and Americans in the lower 48 states next year. In other words, the State Department may have just created 4,000 jobs for them.

SWT is the largest category within the State Department’s Exchange Visitor Program (EVP), which was created to facilitate educational and cultural exchanges between Americans and people from around the world. The SWT, one of 16 different EVP categories, allows college students from abroad to experience American culture by working full time in the United States for four months. To give you an idea about the size of the SWT program, there were 109,000 SWT students working in the United States last year out of the total 324,000 exchange visitors with J-1 visas.

The SWT program has been quite popular among employers across the country (the program peaked at over 150,000 workers in 2008), and it’s easy to understand why. Employers use the SWT program because it’s an easier, cheaper alternative to recruiting and hiring U.S. workers. Because of this, a few months ago I argued at length in support of the State Department’s then-rumored move to ban fish processing jobs from the SWT program. I noted (among other things) that there are plenty of unemployed young workers available in Alaska and the lower 48 states—and that fish processors should improve and increase their recruitment efforts to find them before filling those jobs with temporary foreign workers who are in the country on an exchange program.

A recent report in the Anchorage Press indicates that seafood companies will do fine employing Americans instead of SWT workers. Read more

Parade Magazine decries poor state of public school facilities

Parade Magazine published an excellent report by Barry Yeoman about the sad state of the nation’s school facilities this past weekend. It’s a surprisingly detailed look at a deficit—the backlog in school maintenance and repair—with much bigger consequences for our children than the federal budget deficit. By some estimates, the nation would have to spend $271 billion just to bring the public schools up to a decent state of repair, while a state of world class excellence would require investments several times larger.

All of the talk about testing our way to educational excellence has only diverted attention and funding from the desperate state of the nation’s school buildings and grounds. Crumbling, antiquated facilities are, as Yeoman makes clear, hostile to learning and depressing to the children and teachers who spend so much of their lives there.

State and local governments too often look the other way or blame teachers for the educational shortcomings of the students. Education seems to be the place where many people don’t believe “you get what you pay for.”

Today, more than 14 million children attend class in deteriorating facilities; the average U.S. public school is over 40 years old. In the worst of them, sewage backs up into halls and classrooms, rain pours through leaky roofs and ruins computers and books, and sinks are off the walls in the bathrooms. As Mary Filardo, CEO of the 21st Century School Fund, puts it, they are “unhealthy, unsafe, depressing places.”

It doesn’t have to be that way, and with Filardo’s leadership and encouragement, the Obama administration and key members of Congress are working to close this investment deficit. Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio), Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-Conn.), and dozens of cosponsors have introduced legislation (Fix America’s Schools Today, or FAST) to provide $30 billion a year to repair and renovate school facilities, bring them up to code, and make important energy-saving improvements. These funds would not just improve the health and safety and learning environments of millions of students and teachers, they would also employ 300,000 people to do construction and maintenance work. FAST would have very positive effects on the labor market and the economy.

I hope many of Parade’s 32 million readers are inspired by Yeoman’s article to call or write their senators and congressmen to get their support for FAST. The U.S. is years behind in making these investments, but much better late than never.

What a Romney-Ryan budget would mean for Americans

Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney has selected House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) as his running mate, further elevating tax and budget policy issues. Ryan is known for providing seemingly wonky budget plans over the last decade. Below, we highlight and summarize previous analyses of these plans. What stands out is that Ryan’s budget blueprints impose huge cuts to non-defense spending yet still fail to address long-run fiscal challenges in any serious way. Further, they clearly exacerbate many pressing economic challenges, like restoring full employment, rebuilding the middle class, and curbing health costs. Lastly, they are often simply incomplete or even dishonest, claiming to hold overall revenue levels constant while offering no tax increases to counterbalance very large tax cuts aimed at the highest-income households. Simply put, the Ryan budgets fail to correctly diagnose the most pressing economic problems facing the U.S. economy, and hence fail to propose real solutions. Here are themes everyone needs to know about the Romney-Ryan agenda for the federal budget, and a 10-point overview of Ryan’s budgets.

- The Ryan budget blueprints would derail economic recovery and lower employment in the near term by prematurely cutting domestic spending.

- Ryan’s budgets make deep cuts to Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security, as well as repeal the Affordable Care Act .

- Ryan has proposed cutting non-defense spending and public investments—areas including education, infrastructure, and scientific research—to implausibly low levels that impede near- and long-term growth.

- Ryan’s budget blueprints shift the burden of taxation from the most upper-income households to the middle class, redistributing wealth up the income distribution.

- Ryan’s budgets appear fiscally responsible on paper only by dissembling which taxes will be raised to cover his enormous cuts to tax bills of high-income households and corporations. Read more

Making the tax code work for the middle class

A few weeks ago at a congressional hearing, Gene Steuerle pointed out that the design of our tax code and safety net can result in low-income households facing high effective marginal tax rates. For example, Steuerle finds that a household whose income rises from $10,000 to $40,000 would actually face a nearly 30 percent marginal tax rate. Factoring in the loss of safety net benefits like nutrition assistance, health insurance coverage, and other program benefits translates into an 82 percent marginal rate. In other words, a household making $10,000 that gets a raise of $30,000 would end up only $5,400 better off.

This happens because much of our social safety net is means tested, meaning that benefits phase out as household income rises. A simple way to solve this problem is to delay the phase-out and extend the schedule, making the benefit in question phase-out more slowly. This would not only tear down the high marginal rate wall between low-income and middle class taxpayers, but would also help middle-income households who have too much income to benefit from social safety net programs but too little income to utilize many of the tax breaks that the tax code provides disproportionately to high-income households. Read more

Bill Keller and Third Way’s misinformed and ironic baby boomer bashing

I know I’m getting to this debate a little late, but it’s too good to pass up. As you may have read, the centrist think tank Third Way recently came out with a paper finding that entitlement spending has crowded out public investments, and therefore Democrats who care about children should endorse cutting health and retirement benefits for the poor and/or elderly. Bill Keller then used the paper as the basis for a New York Times column on how the baby boomer generation is greedy. Dylan Matthews and Jamie Galbraith vehemently disagreed.

Let’s state up front that Keller and Third Way’s concern for our currently-low levels of public investment is totally spot on. We’ve written extensively on how public investments act both as a vital driver of economic growth and how they help push against inequality trends, helping us achieve a future where a higher level of prosperity is shared by more people. EPI has been writing about the deficit in public investment for more than two decades.

But there are two intrinsic problems with the Third Way/Keller narrative. The first is that the data do not really support it at all. Below is their central graph, supposedly proving their point:

I’ve redrawn the graph below, lopping off the data after 2011 because, as I understand it, their point is that historically public investments have been crowded out by entitlement spending, so we should only look at historical data. After all, the point is to look at what has already happened, and once you do that, it’s clear that the data do not at all support Third Way’s hypothesis.Read more

DHS initiative for young unauthorized immigrants is cost-effective and benefits American workers

Next week, about 1.2 million young people who reside in the United States without proper authorization—but who were brought here by their parents when they were children—will be eligible to apply to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) for a discretionary grant of relief from removal (also known as deportation). This relief will be valid for two years and renewable in two-year increments. If granted, beneficiaries would also be eligible for an Employment Authorization Document, which would allow them to work legally in the United States with full labor and employment rights. This will clearly benefit the American workforce, and it’s unlikely to cost a dime of taxpayer money.

On Tuesday, the Migration Policy Institute (MPI) hosted a forum to discuss how DHS’s new process—known officially as the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) initiative—will function in practice. The keynote speaker was Alejandro Mayorkas, Director of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), which is the DHS agency that will process and adjudicate DACA applications. Mayorkas outlined the programmatic aspects of the initiative and its requirements, and four immigration experts offered their thoughts in response. It was a valuable discussion that shed some much-needed light on DACA.

We know from multiple reports that many of those who will seek this type of relief from removal are some of the best and brightest students—and future workers—our country has to offer. They arrived in the United States through no fault of their own, and it would be unjust to send them to a country they barely know or do not remember, and where many would not even know the language. They deserve to stay here and to become Americans, and to be allowed to contribute to our labor market. But despite bipartisan support and a decade’s worth of bipartisan proposals in Congress, gridlock and obstructionism have blocked a solution that would grant them a permanent status. That’s one of the reasons why President Obama announced on June 15 that his administration would use its discretionary administrative authority to refrain from removing young unauthorized immigrants who are not criminals and pose no threat to national security.

However, it is clear that USCIS has quite a task on its hands. Read more

For-profit colleges have the poorest students and richest leaders

For-profit colleges prey on the poorest students while generating a great deal of wealth to shareholders, owners, and CEOs. Figure A shows that in 2008, the median family income of students attending for-profit colleges was $22,932. This amount is only slightly higher than the U.S. Census Bureau’s poverty threshold for a family of four. The families of students at public colleges had about twice as much income, and those at private non-profit colleges nearly three times as much.

Despite having the poorest student bodies, the CEOs running for-profit education companies earn far more than the richest leaders of traditional public and private colleges and universities. CEOs of publicly-traded for-profit education companies had an average compensation of $7.3 million in 2009, while the richest five leaders of private non-profit colleges and universities had an average compensation of $3 million (Figure B). The richest five leaders of public universities had an average compensation of $1 million.

For-profit colleges are so profitable because they charge very high tuition and invest rather little in education. Among for-profit college students, 96 percent take out student loans to pay for their education, a much higher rate than at other colleges. Since most of these loans are from the Department of Education financial aid program or U.S. military educational programs, it is ultimately taxpayers who are paying these CEOs’ salaries. These students who were already low-income often end up saddled with a very large amount of debt. Since student loan debt cannot be expunged even through bankruptcy, these debts can be “a lifelong drag on people who already are struggling.”

High cost and high debt for students at for-profit colleges

For-profit colleges tend to enroll students who are not familiar with traditional higher education. They are more likely to be low-income, African American or Latino. Significant numbers of veterans also enroll in these schools. The Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions found that recruiters “were trained to locate and push on the pain in students’ lives.” Additionally, undercover recordings by the Government Accountability Office and other sources show that many for-profit college recruiters “misled prospective students with regard to the cost of the program, the availability and obligations of Federal aid, the time to complete the program, the completion rates of other students, the job placement rate of other students, the transferability of the credit, or the reputation and accreditation of the school.”

This combination of naïve students and misleading information allows for-profit colleges to set tuition in line with their profit goals (many of these colleges are publicly-traded companies) rather than in line with the cost of education. Figure A shows that the average cost of a certificate program at a for-profit college is 4.7 times the cost of an equivalent program at a public community college. The average cost of an associate degree is 4.2 times what it would cost at a typical community college. Bachelor’s degree programs average 19 percent higher at a for-profit college than at a flagship state public university.

Investment, employment trends belie claims that regulation and ‘too much government’ impede recovery

The claim that an excess of regulatory activity is stifling the economy and jobs growth continues to ignore the roots of the economy’s problems (the collapse of the housing and financial sectors) and the reality of current economic trends. We will save discussion of the causes of the downturn for a different day, except for noting the irony that regulatory opponents are fighting implementation of the stronger financial rules that could help prevent future collapses. Instead, we will update key information from a previous EPI analysis of whether business decisions, specifically investments, are consistent with the excessive regulation story. The earlier report documented that “what employers are doing in terms of hiring and investment” was inconsistent with business claims that regulatory uncertainty under the Obama administration was impeding job growth. The new data include four additional quarters of results and also take into account revisions to the earlier data that were made available in late July (the Bureau of Economic Analysis annual benchmarking of the National Income and Product Accounts data leads to some revisions). Altogether, we are now able to compare investment trends during the first 12 quarters (or three years) of this recovery to the first 12 quarters of the three prior recoveries.

Of particular interest is whether businesses are holding back from investing in equipment and software because of fears of new or potential regulations. This investment category leaves out residential investment and investments in business “structures”—because those types of investments are clearly faltering as a result of the bursting of the residential and commercial real estate bubble (and not because of regulatory activity).

As a share of the economy, the data show that equipment and software investment has increased more in this recovery than in the three prior recoveries. Indeed, three years into this recovery the growth of 1.6 percentage points in the share of GDP going to investment in equipment and software is more than twice as large as the growth during the first three years of either the George W. Bush or the Reagan recoveries. That means that this recovery, with the Obama regulatory approach, is far more investment-led than the recoveries under the generally deregulatory Bush and Reagan administrations.

Keep your government hands on my Medicare!

Celebrating Medicare and Medicaid’s 47th birthday this week, here are some quick thoughts on government’s role in ensuring access to affordable health care:

- The United States spends nearly double what other countries spend. Americans spent a total of around $7,600 per person on health care in 2010, compared with around $3,900 on average for countries with similar standards of living, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Despite this higher spending, health outcomes are no better than in other developed countries.

- Government picks up nearly half the tab. As fewer Americans are covered by employer-sponsored insurance, government has taken up the slack. State and federal programs now directly or indirectly cover 45 percent of health care costs in the United States.

- High and rising health care costs are the biggest fiscal challenge our country faces. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that federal spending on major health programs will increase from 7.4 percent of GDP in 2022 to 10.4 percent in 2037 if current policies remain in place. Nearly two-thirds of this increase is due to the assumption that per capita health care expenditures will grow faster than per capita GDP. In the absence of this excess cost inflation, spending on these programs would increase to a more manageable 8.6 percent of GDP in 2037, largely reflecting the long-anticipated baby boomer retirement. Read more

The folly of the GOP’s ‘tax reform’ agenda

Mitt Romney and House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) are both pushing “tax reform” plans that would lower marginal tax rates while broadening the base (curbing tax deductions, credits, and exclusions). Romney’s plan, for example, would reduce all individual income tax rates by a fifth—e.g., the top 35 percent rate would fall to 28 percent—and the revenue loss would be made up by limiting or eliminating unspecified tax expenditures. And he says he would do this without cutting taxes for high-income households (beyond continuing their Bush-era tax cuts), meaning that he would more or less preserve the progressivity of the current tax code (i.e., tax burden distribution).

For the moment, let’s leave aside the fact that these plans neglect to raise a dollar in additional revenue at a time when we need more revenue to put the government on a sustainable fiscal path. Why are these proposals pure folly? First, because they’re obviously not serious—if they were, the plans would lead with the tax expenditure reform rather than the rate cuts. Instead, they’re sold in manner suggesting that Romney and Ryan wanted to propose big across-the-board tax cuts but didn’t want to be seen as blowing up the deficit, so they included vague language on base-broadening in order to ignore the monumental cost of slashing tax rates.

But most importantly, these plans aren’t serious because their stated intent isn’t mathematically possible. In an analysis released Wednesday, researchers at Brookings and the Tax Policy Center analyzed a plan that is consistent with Romney’s proposal, including lowering rates by a fifth and eliminating the Alternative Minimum Tax. The researchers then attempted to construct a base-broadening approach to both make up the revenue lost from the rate cuts and maintain the progressivity of the current tax code. Read more

Potential failure

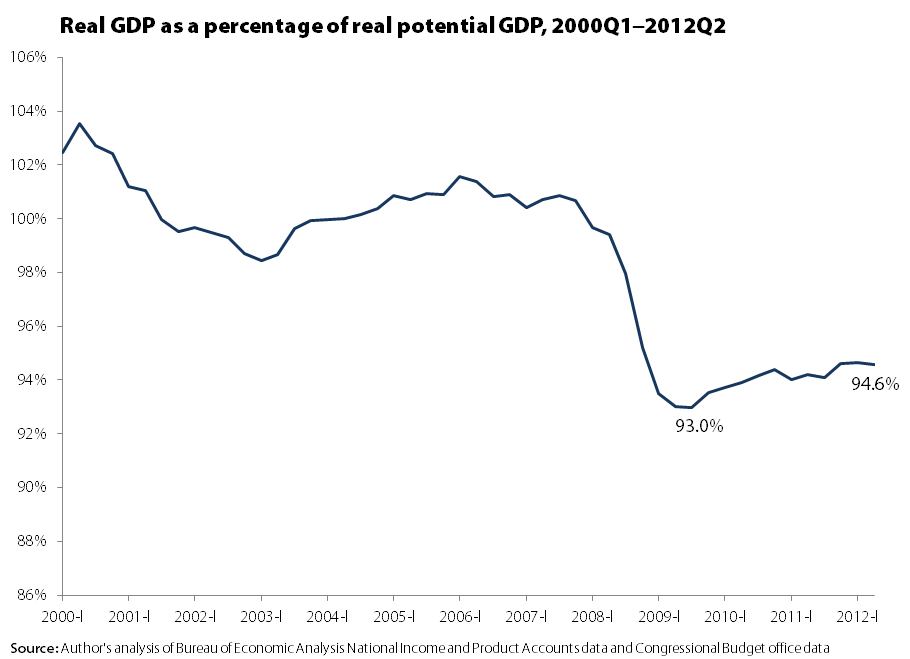

Today’s report on gross domestic product (GDP) came with more news of disappointing growth. The economy has grown at an average rate of 1.75 percent so far this year. While the economy is growing and we are not in a recession (and there’s no sign a recession is imminent), it is important to note that this slow growth is not moving the economy much closer to full health, and may even be doing real damage to that long-run health.

This problem can be highlighted by looking at actual GDP as a percentage of “potential ” GDP, a figure provided by the Congressional Budget Office. Potential GDP can be thought of as a capacity utilization rate for the whole economy: If we were utilizing all of our resources, including labor and capital, how much economic output would we be able to produce?

You can see that in 2000, actual and potential were roughly similar (actual slightly exceeds potential, in fact, because the CBO has a too-conservative view of what is the lowest sustainable rate of unemployment), but then this ratio crashes as the Great Recession hits.

At the trough of the recession in the third quarter of 2009, the U.S. economy was operating at only 93 percent of potential. In the nearly three years since, we’ve only recouped an additional 1.6 percent of potential output. Although GDP has been growing in that period, potential has been growing too (and faster), because of our increasing potential labor force and productivity growth.

Investigations reveal forced labor of immigrants but Congress won’t allow the Labor Department to combat it

Congress holds the keys to fixing many of the problems in one of the main temporary foreign worker programs used by employers to displace U.S. workers, depress wages, and exploit foreign workers. The Department of Labor has already issued the important fixes, but they’ve been temporarily enjoined by a federal court. However, going forward, Congress is considering nullifying the rules entirely by denying funding for their implementation.

The program in question is the H-2B guest worker program. On Tuesday, I joined the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), the AFL-CIO, and two H-2B guest workers from Central America at the National Press Club to call on Congress to help unemployed workers have increased access to jobs in a number of occupations—including landscaping, hospitality, forestry, and seafood processing—by allowing the DOL’s new rules governing the H-2B program to come into force. The new rules would require employers to first recruit unemployed workers before turning to foreign workers, ensure that U.S. and foreign workers are not underpaid, and protect guest workers from becoming victims of forced labor and human trafficking, as well as from being retaliated against if they attempt to assert their labor and employment rights.

Although the new rules include common sense protections for U.S. and foreign guest workers, they are far from extreme or burdensome. If anything, the rules and requirements on employers are quite basic and modest.

Recently, the scandalous side of the H-2B program received some well-deserved attention from the media. A few weeks ago, a New York Times editorial, “Forced Labor on American Shores,” offered a powerful and depressing reminder that the days of forced labor (also known as slavery) are still with us. In fact, the H-2B guest worker program helps facilitate it, and in the editorial’s case, forced labor was occurring for the benefit of Walmart, the largest private employer in the world, by C.J.’s Seafood, one of its suppliers. Walmart’s size and purchasing power give it leverage to demand the lowest prices possible from its vendors and manufacturers. This in turn, can motivate suppliers like C.J.’s in Louisiana to exploit and abuse their workers in order to bring down labor costs. Read more

Confirming the further redistribution of wealth upward

A new Congressional Research Service report by Linda Levine is the first update on the distribution of wealth (including that of the top 1 percent) I’ve seen based on the recently released Federal Reserve Board (FRB) data on wealth for 2010. Levine’s analysis (see two of her tables below) shows a large upward change in the distribution of wealth over 2007-2010, with losses in the bottom 90 percent and large gains for the top 10 percent. Specifically, the bottom 90 percent in 2010 had just 25.4 percent of all wealth, down from 28.5 percent in 2007. The gainers were primarily those in the 90-to-99th percentiles (up 2.3 percentage points) of wealth, though the top 1 percent saw gains (up 0.7 percentage points) too. Levine’s data goes back to 1989 and show the wealth share of the bottom 90 percent to be at its lowest in 2010, far lower than the 32.9 percent share in both 1989 and 1992.

Levine reports data directly from the FRB showing that average wealth is down from 2007 but still far greater in 2010 ( $498,800) than in 1989 ($313,600) or 1992 ($282,900). In contrast, the wealth of the median household (wealthier than half of households but less wealthy than the other half) in 2010 was $77,300, not much different than in 1989 ($79,100) or 1992 ($75,100). In other words, wealth grew 59 percent from 1989 to 2007, but the typical household’s wealth was actually 2 percent less.

This is yet another dimension of the same old story about the economy being able to provide for most people but failing to do so, a story that will be told more fully in the forthcoming State of Working America (being released in late August). The new edition will include a more detailed report on wealth distribution from 1962 to 2010, based on an analysis by New York University’s Edward Wolff (see the last report, written by Sylvia Allegretto).

Happy birthday, CFPB

Tomorrow, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau completes its first year of operation. Created under the Dodd-Frank Act, we’re starting to see the benefits of a strong federal agency that protects consumers from the dangers posed by an unchecked financial industry.

The CFPB notched its first enforcement action—and hopefully, the first of many—yesterday with the announcement that Capital One will pay up to $210 million to settle federal charges that it violated consumer protection requirements. According to CFPB charges, Capital One used “deceptive practices” to sell unnecessary add-ons to credit card holders. Between $140 million and $150 million will be paid to the two million customers affected. Capital One will pay another $60 million in fines, with $25 million going to the CFPB and $35 million to the bank-regulating Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

Today, the CFPB followed up this victory with the release of a report on the private student loan industry, to which American consumers owe more than $150 billion in debt. The extensive report identifies several consumer protection issues in the private student loan marketplace. Importantly, though, the report doesn’t just stop there: It includes strong congressional policy recommendations by CFPB Director Richard Cordray and Secretary of Education Arne Duncan.

These actions by the CFPB are encouraging, but the history of financial regulation teaches us that the real challenge is maintaining vigilance over time. This means keeping up with financial intermediaries’ attempts to arbitrage between different regulatory agencies, bypass current regulatory structures, and capture regulating agencies. The CFPB had a good first year, but the real challenges will appear in the years to come.

Nearly 3 years, and counting: Minimum wage increase helps working families and the economy

At the end of March, Iowa Sen. Tom Harkin introduced the Rebuild America Act, a bill that contains important provisions to strengthen the economy and improve the well-being of working Americans. Among the many worthy elements of this bill is a proposal to increase the federal minimum wage to $9.80 by July 1, 2014. Next week will mark the third anniversary of the most recent increase in the federal minimum wage. Rather than increase the federal minimum wage annually to allow low-income workers to maintain their standard of living and share in the fruits of their ever-more productive labor as should be the case, Congress too often raises the minimum wage and then puts the well-being of low-wage workers on the back burner for years at a stretch.

As my colleague David Cooper wrote in April, increasing the federal minimum wage to $9.80 by July 1, 2014 would benefit over 28 million workers and increase national GDP by over $25 billion, in the process creating over 100,000 jobs. Given the lackluster recovery that continues to cast a pall over the nation, this positive step should be embraced by all those who care about the well-being of working families.

In a forthcoming paper, I’ll be detailing the demographic characteristics of those affected by increasing the minimum wage as proposed by Harkin (a proposal that has been mirrored in Conn. Rep. Rosa DeLauro’s Rebuild America Act and in a bill for which Calif. Rep. George Miller is currently gathering support). This paper will also highlight the state level impact of the proposed increase, breaking out state-specific demographic impacts and also highlighting the economic and employment impacts.

Here are a few graphs to whet your collective appetites:

Figure 1: Educational attainment

As seen in Figure 1, over three-quarters of those affected by the proposed increase to $9.80 have completed high school or more, including 42.3 percent who have completed some college, have an associates degree, a bachelor’s degree, or more. Read more

80% of jobs created since the recession’s end have gone to men?

The U.S. economy has created 2.6 million net jobs since the end of the Great Recession in June 2009. According to a Los Angeles Times analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics data, men have filled 2.07 million of these new jobs. There are several possible explanations for this, and a couple of important points to keep this disparity in context:

- Men suffered higher levels of job loss during the recession than women, and their level of employment today relative to pre-recession levels is still lower than women’s.

- Women hold the majority of jobs in the public sector, which is by far the sector that has seen the worst performance since the recovery began.

- Male-dominated manufacturing is recovering, albeit slowly.

- Men are taking jobs in sectors that women have traditionally been the majority in.

The construction sector suffered the largest job losses of any industry during the recession, followed by manufacturing. These sectors are overwhelmingly male, meaning that their initial losses in the recession outpaced losses for women. Even today, unemployment among men is 8.4 percent, while for women it’s 8.0 percent.

Because women have historically filled the majority of public-sector jobs, they’ve been disproportionately affected by state and local governments’ decisions to cut positions in the wake of state fiscal troubles—a phenomenon that has largely occurred since the recession’s end. An EPI report from May found that of the 765,000 public-sector jobs lost between 2007 and 2011, 70 percent were jobs held by women. While the private sector has slowly recovered some of the jobs it lost during the recession, the public sector is still cutting them at a rapid rate; 2011 was the worst public-sector job decline on record. This public-sector employment loss is almost surely the single largest reason for women’s comparative struggles since the recovery began. Read more