Recent federal regulation coincides with manufacturing employment gains

The National Association of Manufacturers is showing itself to be less a genuine representative of the nation’s manufacturing businesses than a political entity tied to the Republican Party. Despite the evidence that the Obama administration imposed fewer regulations in its first three years than the Bush administration, the NAM complains constantly about the regulatory burden Obama is imposing. In its own words: “New Survey Paints Bleak Picture Before 2012 Elections.”

This is especially surprising since we heard no such complaints at the end of George Bush’s first term.

It begins to look hypocritical and totally political when we consider that each year of the Bush administration resulted in a year-over-year loss of manufacturing jobs, a streak that ended only after Obama’s auto bailout and Recovery Act took effect. Over the last two years, manufacturing employment grew from 11,340,000 to 12,074,000, a gain of more than 700,000 jobs.

Looking at these data, it is hard to conclude that the increasing regulatory burden of the last few years—if there has been an increase, as NAM claims—has hurt manufacturing.

Video: Collective bargaining and shared prosperity in Michigan

The decline of collective bargaining and the erosion of middle-class incomes in Michigan, an EPI briefing paper published today, finds that the divergence between pay and productivity and the corresponding failure of middle-class incomes to grow is strongly related to the erosion of collective bargaining over the last 30 years in Michigan. Included in the paper is this video produced by Colin Gordon, Professor of History at the University of Iowa:

Nearly four years in, what do cost-benefit data show for the major Obama EPA rules, and what do they imply for the economy?

With the issuance in August of the fuel efficiency and greenhouse gas standards for cars for model years 2017–2025, the Obama administration may have now put forth the last major Environmental Protection Agency rule of its term. Starting with a comprehensive analysis in May 2011, EPI has issued a series of analyses which have found that contrary to much of the political commentary, these rules will be of great benefit to the nation, improving public health considerably without harming the economy or employment.

Altogether, under the Obama administration, 10 final major rules have now been issued by the EPA and three final major rules issued jointly by EPA and the Department of Transportation. To examine one way that the impacts on society of those rules are assessed, I add up their ultimate annualized cost and benefit figures. It bears mentioning that costs and benefits are phased in over time, can jump around for individual rules from year to year, and a considerable portion of the impact of the rules will not occur until five years or more from now. Thus it is best to think of the figures as annual averages over time, but not representative of a particular year.

The table below, using the official government data, indicates:

- The benefits of the finalized Obama EPA rules are valued at $144 billion a year Read more

Retirement proposals a big step forward

Recent policy initiatives in the retirement arena, while they may not go far enough, would have an immediate impact on workers’ retirement security while pointing the way forward rather than closing off avenues for further reform.

A critical difference between these plans and more incremental reforms is that they don’t just focus on increasing retirement savings through automatic enrollment or reducing costs through fee transparency and other means, but also provide workers with a cost-effective way to insure against longevity and investment risks. While workers in 401(k) plans have always had the option of minimizing risk by investing conservatively and purchasing life annuities in the private insurance market, the cost is prohibitive—roughly double the cost of achieving a similar outcome through a traditional defined benefit pension (Morrissey 2009, Almeida and Fornia 2008).

At the federal level, Sen. Tom Harkin (D-Iowa) has proposed a multi-pronged approach that would expand Social Security while creating USA Retirement Funds (U.S. Senate HELP Committee 2012). In addition to pooled and professionally managed retirement savings, which have been shown to significantly improve net risk-adjusted returns, USA Retirement Funds would provide lifetime pension benefits based on long-term market conditions. While participants as a group would still bear the risk of prolonged market downturns, this risk would be spread across generations of workers and retirees so that retirement outcomes wouldn’t vary dramatically based on whether a worker retired in the wake of a bull or bear market. Read more

What we read today

Here’s some of the thought-provoking content that EPI’s research team came across today:

- “Mitt Romney’s Economic Plan: Win, Then Do Nothing” (The Atlantic)

- “Taxes and the Economy: An Economic Analysis of the Top Tax Rates Since 1945” (Congressional Research Service)

- “Important New Research On a Key Fiscal Cliff Issue” (Jared Bernstein’s On the Economy)

- And finally, this video from the National Academy of Social Insurance:

Foxconn riot, strikes, coerced student labor, and more: All’s not well with iPhone 5 production

The latest red flag that all is not well with iPhone 5 production is the overnight riot that occurred at the dormitory of one of Foxconn’s plants in China that “makes parts for Apple’s iPhones and hardware for other companies” (quoting from NPR). According to Reuters, this riot involved 2,000 workers, was broken up by about 5,000 police, and the factory has been shut down for an indeterminate length of time.

The proximate cause of the riot is not yet clear; Foxconn said “the trouble started with a personal row that blew up into a brawl,” but Twitter-like postings claimed that “factory guards had beaten workers and that sparked the melee” (both quotes from the Reuters story). It is, of course, particularly difficult to obtain accurate, unbiased information of conditions at factories in China. At minimum, however, the severity of the riot demands an independent investigation and should give anyone pause before concluding that any worker rights concerns connected to the production of iPhones by Foxconn have been addressed.

Such pause is especially appropriate given other information that has come to light in the past two weeks. Read more

2011 American Community Survey shows continuing hardship throughout the U.S.

The results of the 2011 American Community Survey (ACS), released today by the U.S. Census Bureau, show that households across the United States are still coping with the damage wrought by the Great Recession.

Between 2010 and 2011, inflation-adjusted median household income either fell or stayed the same in every state except Vermont. Median household income significantly declined in 18 states, ranging from a 1.1 percent decline in Ohio to a 6 percent drop in Nevada. California (-3.8 percent), Georgia (-3.5 percent), Hawaii (-5.2 percent), Louisiana (-4.7 percent), New Jersey (-3.4 percent), and New Mexico (-3.1 percent) all experienced income declines of more than 3 percent. Thirty-one states showed no significant change in median household income. For the nation as a whole, median household income decreased by 1.3 percent.1

While overall household incomes declined, the distribution of income still became more inequitable. Twenty states saw a significant increase in income inequality as measured by the Gini index2: Arkansas, California, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Maine, Michigan, Nebraska, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Tennessee, Texas, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. Income inequality did not decrease in any states nationwide.

The survey’s poverty results show similar cause for alarm. At the state level, both the number and percentage of people in poverty rose significantly in 17 states, with the largest increases occurring in Louisiana (+1.7 percent), Oregon (+1.6 percent), and Arizona (+1.5 percent). Vermont (-1.2 percent) was the only state where the poverty rate declined. Read more

New evidence of disturbing working conditions in iPhone production

“It is disappointing that no matter how advanced the technology introduced by Apple is, the old problems in working conditions remain at its major supplier Foxconn.” — SACOM, Sept. 20, 2012

In Sept. 2012, researchers from the Hong Kong-based Students and Scholars Against Corporate Misbehaviour (SACOM) conducted off-site interviews at Foxconn’s plants in Zhengzhou, China; the sole product of these plants is the iPhone. SACOM just released the findings of its interviews, New iPhone, Old Abuses: Have Working Conditions at Foxconn in China Improved? The report (sometimes quoted verbatim below) indicates:

- Overtime work is excessive, and well above that permitted by Chinese law. Monthly overtime hours have been between 80–100 hours in some of the production lines. This is two to three times the amount (36 hours) allowed by Chinese law. Workers often only get one day off every 13 days.

- Overtime work is often unpaid. Workers have to attend the daily work assembly meeting without payment. Also, on some production lines, workers must reach their work quota before they can stop working even if that means working overtime without pay. Read more

Majority of elderly households fall into category maligned by Romney

As our blog noted Tuesday, the 47 percent of Americans that Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney dismisses as “dependent” on government because they don’t pay income taxes includes many elderly households. Romney concludes his remarks on the 47 percent by saying, “My job is not to worry about those people. … I’ll never convince them that they should take personal responsibility and care for their lives.”

Romney may not realize this, but a majority of the elderly fall into this category. The nonpartisan Tax Policy Center found that in 2011, 55.9 percent of elderly households paid no federal income taxes, compared to 43.9 percent of nonelderly households. In fact, as the graph below shows, at nearly every income level, the elderly are more likely to pay no federal income tax. Furthermore, nearly two-thirds of elderly units have cash incomes under $50,000, where the difference between the two groups is the greatest.

This largely reflects intentional features of the tax code to reduce elderly tax burdens. Read more

Romney’s regressive socioeconomic philosophy is nothing new

Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney is taking much deserved flack for the leaked video of him professing—at a $50,000 a plate fundraiser—utter disdain for the less fortunate half of the population. The tax policy issues at stake have been well covered: my colleague Ethan Pollack and Ezra Klein both have graphical dissections of who the 47 percent of households are and why they do not earn enough to owe federal income tax liability, and Ruth Marcus poses four poignant questions deserving answers from the Romney camp on the tax policy implications of his remarks. I’ve explained in the past why this misleading conservative grievance is a red herring. And as Rob Reich points out, Romney’s remarks incoherently conflate the 47 percent not paying income taxes with “entitled” recipients of government programs, ignoring that “entitlements”—Medicare, Social Security, and unemployment insurance—are funded by payroll taxes. But there’s a much broader point than the tax policy issues being hashed out in the blogosphere and op-ed pages: Romney’s prior comments, budget proposals, and selection of running mate all suggest the same antipathy toward the poor and the middle class.

Romney landed himself in hot water last February when he shrugged off the plight of the poor alongside the fortune of the wealthy: “I’m not concerned about the very poor—we have a safety net there. If it needs repair, I’ll fix it. … We have a very ample safety net … we have food stamps, we have Medicaid, we have housing vouchers…” After widespread backlash for these remarks, Romney clarified what he meant: “My focus is on middle income Americans. We do have a safety net for the very poor and I said if there are holes in it, I want to correct that.” So how would his budget “repair” the safety net?Read more

Five facts about the 47 percent

For those of you that aren’t news junkies, Mitt Romney was caught on tape at a May 17 fundraiser proclaiming: “Forty-seven percent of Americans pay no income tax. So our message of low taxes doesn’t connect. … My job is not to worry about those people. I’ll never convince them that they should take personal responsibility and care for their lives.” Here’s a look at these 47 percent of Americans and why his suggestion that they don’t take personal responsibility for their lives is complete nonsense.

1) The 47 percent are mostly employed or elderly: More than 80 percent of the 47 percent that don’t pay federal income tax are either elderly or are employed (and thus still pay the payroll tax). The remaining tax units overwhelmingly make less than $20,000 a year (which is below the federal poverty line for a family of four).

2) Today’s nontaxpayers (federal income tax, that is) are tomorrow’s or yesterday’s taxpayers. Contrary to Romney’s implication, these are not two distinct groups; rather, people go back and forth between the two groups over their lifetime. In fact, most of the 47 percent are either seniors who already paid federal income taxes over the course of their working life or young people who will do so once they hit their mid-20s. By the time they reach 50, there’s a nearly 80 percent chance they’ll be paying the federal income tax.Read more

No, we’re nowhere close to the limits of effective fiscal stimulus

Robert Samuelson’s op-ed in Sunday’s Washington Post argues that the United States has reached or passed “the practical limits of ‘economic stimulus.’” He’s wrong, and much of the evidence he points to on the fiscal side ranges between grossly misleading and simply inaccurate. Several points:

- More fiscal expansion—particularly deficit-financed spending on infrastructure, aid to states, safety net spending, and well-targeted tax cuts—would accelerate economic growth and boost employment. This may be disputed on editorial pages, but it is not disputed by economists paid for their economic analysis. See analyses from Moody’s Analytics, Macroeconomic Advisers, or EPI’s own analysis of President Obama’s American Jobs Act, most of which Congress has not acted upon. Claims to the contrary are also belied by concern about the so-called “fiscal cliff” professed by both sides of the political aisle; politicians are worried that budget deficits closing too quickly will push the economy into a double-dip recession, as the Congressional Budget Office has forecast under its current law baseline.

- The point of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) and subsequent ad hoc fiscal stimulus was to boost aggregate demand, not primarily “to inspire optimism by demonstrating government’s commitment to recovery.” Increased aggregate demand from ARRA kicking in and ramping up was responsible for arresting the economy’s rapid contraction in 2009 and the simultaneous deceleration (and eventual reversal) of job losses, not the confidence fairy.Read more

Obama tackles illegal Chinese auto parts subsidies

The Obama administration announced another trade case against China, this one focused on China’s blatant, illegal subsidies to exporters of auto parts. These subsidies have helped China take a growing share of the huge U.S. auto parts market, at a cost of tens of thousands of good manufacturing jobs. EPI researchers reported on the breadth and depth of these illegal subsidies earlier this year and warned that they threatened to decimate employment in the U.S. industry just as it got back to its feet after the Great Recession. As EPI’s Rob Scott and Hilary Wething wrote in January: “Chinese auto-parts exports increased more than 900 percent from 2000 to 2010, largely because the Chinese central and local governments heavily subsidize the country’s auto-parts industry; they provided $27.5 billion in subsidies between 2001 and 2010 (Haley 2012).” The U.S. trade deficit in auto parts with China reached $9.1 billion in 2010 and has continued to grow.

It’s great to see President Obama stand up for fair trade, even if the timing is provoking some skepticism in the media. As I’ve pointed out to several reporters, Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney has been calling on Obama to get tougher on China’s unfair trade practices. Romney can hardly complain when the president does exactly what Romney recommends. And with tens of thousands of good jobs at stake, it would have made no sense for Obama to delay this case until after the election; every month of delay would just mean more bankrupt manufacturers, more plant closings, and more jobs lost.

The administration, following its standard, cautious practice, has not tackled the full extent of illegal Chinese subsidies. Rather, it’s gone after the low-hanging fruit, the clearly prohibited, high-profile, publicly reported, targeted subsidies that depend on export volume. There’s much more to do. In a report for EPI, Usha Haley, Professor of International Business at Massey University in New Zealand, documented more than $27 billion in Chinese government subsidies to the auto parts industry from 2001 to 2011 and identified another $11 billion in subsidies planned for the future. Preventing this massive intervention will be critical if the U.S. auto parts industry is to get back on its feet, let alone to thrive and grow. The case announced today was a logical place to start.

One year of Occupy Wall Street

I’m told that it’s the one-year anniversary of the beginning of the Occupy Wall Street (OWS) activities. Smarter political minds than mine can tell you why OWS either mattered or not, or matters still or not. My quick take on them (a wholly unoriginal one) is that they introduced an element into the economic conversation that was not simply obsessing about the size of the budget deficit and how to reduce it.

Given that this deficit conversation was inane and destructive, the OWS movement deserves great credit for breaking it up. Further, given that the element OWS introduced in the nation’s conversation—the growth of inequality in recent decades—is the most important economic trend in the past generation, they deserve even further credit; they didn’t just interrupt a dumb conversation, they tried to start a relevant one.

We tried to argue that many of the claims of the OWS movement were well-supported by economic-data—see our paper here. Since then, we have released our newest edition of The State of Working America—see the website (and data) here—which further cements the case that inequality was the primary barrier to decent growth in low– and middle-income households living standards, and which links the growth of this inequality to intentional policy decisions made explicitly to redistribute income upwards. Read more

Items I wish the education pundits would read

Four years ago, we published Grading Education: Getting Accountability Right. We surveyed national samples of adults, school superintendents, state legislators and school board members and concluded that they all supported a balanced set of goals for public education, including not only basic skills but also reasoning, social skills, preparation for civic participation, a good work ethic, good physical and emotional health, and appreciation of the arts and literature. Accountability systems based heavily on basic math and reading skills will undermine these balanced goals by creating incentives to shift instruction towards those aspects of the curriculum on which the school or teachers are being evaluated.

You can read the introduction and summary of Grading Education for more. You can also look at a summary of the goals survey. In addition, a chapter summarizing how other fields—medicine, job training, law enforcement—have learned about the dangers of standardized accountability was published separately. And an appendix reprints a sample of letters and statements we have received from teachers describing how standardized testing, and preparation for it, has destroyed creative and successful curricula and instruction nationwide.

EPI assembled a group of prominent testing experts and education policy experts to assess the research evidence on the use of test scores to evaluate teachers.Read more

The value of Fed-talk

Ben Bernanke made news yesterday by committing to provide more accommodative monetary policy in an effort to spur a faster recovery—and specifically linking his moves to the Federal Reserve’s disappointment in the labor market recovery so far.

This is a welcome, if still insufficient, development.

Bernanke’s move comes after a widely-circulated paper by Michael Woodford was presented at the Fed’s Jackson Hole conference. The paper argued that the main beneficial impact of Fed easing was through its impact on expectations—that is, if the Fed could convince the public that it will not pull the plug on its support to the economy even if inflation begins to pick up, then they can convince businesses and households to start spending (the mechanisms is that the higher expected inflation rates can drive real interest rates lower even as the Fed’s nominal policy interest rates are stuck at zero). Woodford argues that the most powerful way these expectations are changed are simply through the Fed’s “forward guidance,” or, well, talking.

This raises two quick issues. Read more

Teacher accountability and the Chicago teachers strike

It was bound to happen, whether in Chicago or elsewhere. What is surprising about the Chicago teachers’ strike is that something like this did not happen sooner.

The strike represents the first open rebellion of teachers nationwide over efforts to evaluate, punish and reward them based on their students’ scores on standardized tests of low-level basic skills in math and reading. Teachers’ discontent has been simmering now for a decade, but it took a well-organized union to give that discontent practical expression. For those who have doubts about why teachers need unions, the Chicago strike is an important lesson.

Nobody can say how widespread discontent might be. Reformers can certainly point to teachers who say that the pressure of standardized testing has been useful, has forced them to pay attention to students they previously ignored, and could rid their schools of lazy and incompetent teachers.

But I frequently get letters from teachers, and speak with teachers across the country who claim to have been successful educators and who are now demoralized by the transformation of teaching from a craft employing skill and empathy into routinized drill instruction using scripted curriculum.Read more

Chicago’s schools and the polite Pinkertons of educational reform

Rebecca Mead understands what too many of my friends do not. In an excellent blog post for the New Yorker, Mead warns that the neo-liberal education “reform” movement is not primarily about improving educational opportunities for poor, urban minority students. It’s about breaking teachers unions.

Chicago is currently ground zero for the so-called reformers, and Mayor Rahm Emanuel is their latest champion, picking up the same cudgel that Joel Klein and Michelle Rhee wielded in New York and Washington, D.C. Emanuel has provoked a strike by 29,000 school teachers, refusing to settle unless the teachers’ union gives in to high stakes testing.

Rhee once admitted that she would be happy to see the entire D.C. school system turned over to private charter schools, and my guess is that Emanuel feels the same way about Chicago. Chicago’s public school teachers, who devote their lives to the education of the city’s poor, mostly minority children, know the direction Emanuel and his school CEO are heading; they’ve seen Arne Duncan and his successor close schools, charterize schools, increase class sizes, and divert money from the school budget.Read more

Lessons for Chicago: It takes a cake, and the truly disadvantaged need extra frosting

As the Chicago public schools teachers strike continues, with no resolution of the conflict in sight, the mayor and CEO might do well to reflect on two key lessons imparted by a scholar whose research on Chicago school reforms is universally hailed as in-depth, groundbreaking, and unimpeachable. Anthony Bryk is the creator of the Consortium on Chicago School Research and current president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Bryk and his CCSR colleagues’ 2010 book, Organizing Schools for Improvement: Lessons from Chicago, has become a bible for evidence-based education policymakers across the country. While their data and methods are so complex that the authors advise many readers to skip the long chapter explaining them, two key findings jump out as relevant to the battle being waged now in Chicago over the current round of attempted reforms.

First, Bryk says, contrary to current popular reform policies, which advocate relatively quick-fix single-shot changes like replacing teachers or principals, turning over schools to new management, or closing them altogether, improving a school and sustaining those improvements is a complex, long-term process. Indeed, after much mulling, he and his colleagues liken the process most closely to that of baking a cake. It requires five ingredientsRead more

Hispanic and single-black-father families see declines in poverty

Although Hispanic and black families have the highest poverty rates of the major racial and ethnic minorities, the latest poverty data holds some positive news. The poverty rate for Hispanic families with children under 18 years old declined 1.6 percentage points (Figure A). Black families showed a 1.1 percentage-point decline, but this decline was not statistically significant. Non-Hispanic white and Asian American families had small increases that were not statistically significant.

By family type, for all families with children under 18 years old, only families headed by single1 fathers showed a real decline.Read more

Want to understand today’s inaction in solving economic problems? Read The State of Working America

Everybody knows the most pressing economic problem facing the United States today is joblessness. And many also know that this problem is economically solvable, yet not being solved largely because of political gridlock.

But, some might still find it hard to believe that policymakers could really be so indifferent to the economic struggles of most American families. This is where The State of Working America—released yesterday—comes in handy. Think of it as the Rosetta Stone of American economic policymaking over the past generation. Or just a book and accompanying website with lots and lots of charts and tables. Either way.

The two important points that come through loud and clear from its tracking of trends in income, wages, jobs, wealth and poverty are:

- The primary barrier to low– and middle-income families seeing decent rates of economic growth over most of the last generation was the simple fact that a very narrow slice at the very top claimed a vastly disproportionate share of the fruits of economic growth Read more

By the numbers: New Census Bureau data on poverty, income, and health insurance coverage

This morning’s release by the U.S. Census Bureau of the 2011 data on income, poverty, and health insurance coverage is yet another reminder of the ongoing consequences of both the Great Recession and the weak business cycle that preceded it. A first take:

Poverty

- 15.0%: The share of the population in poverty in 2011

- 21.9%: The percent of children under 18 in poverty

- 46.2 million: The number of people in poverty in 2011

- $22,811: The poverty threshold for a family of four with two children

- 44.0%: The share of the poor population in “deep poverty,” or below half the poverty line

- 2.3 million: The number of people unemployment insurance kept out of poverty in 2011

- 21.4 million: The number of people Social Security kept out of poverty in 2011

- 5.7 million: How many fewer people would be in poverty if the Federal Earned Income Tax Credit was included in the Census definition of money income

- 3.9 million: How many fewer people would be in poverty if food stamps (SNAP) were added to money income

Income

- -1.7%, +5.1%: The change in average household income between 2010 and 2011 for the middle 20 percent, and the top 5 percent, respectively. The disparity means income inequality increased in 2011. Read more

Tax cuts, and debt, and arithmetic: Oh my!

In his Democratic National Convention speech last week, former President Bill Clinton joked about conservatives’ struggle between professed concern about public debt, proposed tax cuts, and arithmetic:

“Somebody says, ‘Oh, we’ve got a big debt problem. We’ve got to reduce the debt.’ So what’s the first thing [Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney] says we’re going to do? ‘Well, to reduce the debt, we’re going to have another $5 trillion in tax cuts, heavily weighted to upper-income people. So we’ll make the debt hole bigger before we start to get out of it.’”

There are plenty of holes in Romney’s plan, which would translate to somewhere between $2.7 trillion and $6.1 trillion in deficit-financed tax cuts over the next decade, relative to current tax policies.1 Within this range, their impact is difficult to quantify because the Romney plan suffers from serious sins of omission.

Romney initially proposed repealing the estate tax; eliminating capital gains, dividends, and interest taxation for households with adjusted gross income under $100,000 ($200,000 for married taxpayers filing jointly); cutting the corporate income tax rate from 35 percent to 25 percent; eliminating the corporate alternative minimum tax (AMT); and repealing new taxes from the Affordable Care Act (ACA). This $2.7 trillion package of tax cuts would be entirely deficit-financed. Read more

iPhone 5 is being produced under harsh working conditions still in violation of basic labor rights

By Scott Nova and Isaac Shapiro

Information from Apple’s own factory auditor, the Fair Labor Association, and new reports in Chinese media show that the iPhone 5 is being produced by employees:

- Who work far more hours than allowed by Chinese law;

- Who are not paid for all the hours they work;

- Who lack any true voice in the workplace to advocate for necessary reforms

- Who partly consist of thousands of students who are being coerced to work, in a practice that Chinese media outlets characterize as “forced labor”

In short, any excitement over any new capabilities of the iPhone 5 demands to be tempered by a realistic appraisal of the unacceptable working conditions for the Chinese workers producing it. These conditions are explained in some detail below; a fuller analysis by our organizations of what changes in labor practices have and have not been made at Foxconn (Apple’s lead supplier in China) over the past year is forthcoming. Read more

Card check survives as way to choose a union

If you believed the Wall Street Journal Washington Wire headline or the rhetoric of Arizona’s attorney general, you’d think the right to use card check to select a union as a bargaining representative had been struck down by a U.S. district court. But it always helps a little to read the court’s decision. And having done so, I’m happy to report that the obituary for card check as a way to select a union was premature, at best.

Arizona, goaded by the Koch brothers and anti-union businesses, passed a constitutional amendment declaring that secret ballot elections are the only permissible way to select an employee representative in Arizona. In other words, card check elections are illegal. (“The right to vote by secret ballot for employee representation is fundamental and shall be guaranteed where local, state or federal law permits or requires elections, designations or authorizations for employee representation.”) Federal law protects card check elections, so the National Labor Relations Board sued Arizona in federal court, and the court issued a decision on Wednesday. Read more

Would full passage of Obama’s Jobs Act have added another million jobs?

In his convention speech last night, former President Bill Clinton claimed that, “We could have done better, but last year the Republicans blocked the President’s job plan, costing the economy more than a million new jobs.” According to Glenn Kessler of the Washington Post’s Fact Checker, this claim was “merely a fuzzy and optimistic projection.” This is flat-wrong, and the evidence cited by Kessler to support his claim is far “fuzzier” than the counterfactual impact of the American Jobs Act (AJA).

The problem revolves around the baseline against which policy changes are scored. With the benefit of hindsight, we know pretty well how many jobs would have been created relative to what actually happened in terms of 2012 policy changes. The article linked to by Kessler, and on which he hangs his criticism, is full of quotes from forecasters saying that the AJA wouldn’t add to jobs because, “Some of this is just extending support that was already in place,” and implicitly would happen anyway. We now know that this is wrong—much of what was called for in the AJA turns out not to have supported the economy in 2012 (because it was never passed). And if it had been, the effects would have been … to add over a million jobs to the economy. Wonky details follow. Read more

Elizabeth Warren on why you should read State of Working America too many American families are struggling to get ahead

People are buzzing about former President Clinton’s speech to the Democratic convention last night. And the man clearly knows how to communicate ideas about economic policy. But for my money, it was Elizabeth Warren who got it spot-on:

“I’m here tonight to talk about hard-working people: people who get up early, stay up late, cook dinner and help out with homework; people who can be counted on to help their kids, their parents, their neighbors, and the lady down the street whose car broke down; people who work their hearts out but are up against a hard truth—the game is rigged against them… It wasn’t always this way.”

This isn’t just a good translation of policy analysis into English—it could also pretty much serve as the press release for a book EPI is officially releasing next week: The State of Working America, 12th edition.

The State of Working America (SWA, around here) is the comprehensive reference tracking trends in wages, incomes, and wealth of American families, and it focuses particular attention on low- and middle-income workers and their families—the same group Warren was talking about last night. We’ve never intended SWA to be a policy manifesto—it has always instead been a “just the facts” kind of project. But this year, we decided to connect some awfully obvious dotsRead more

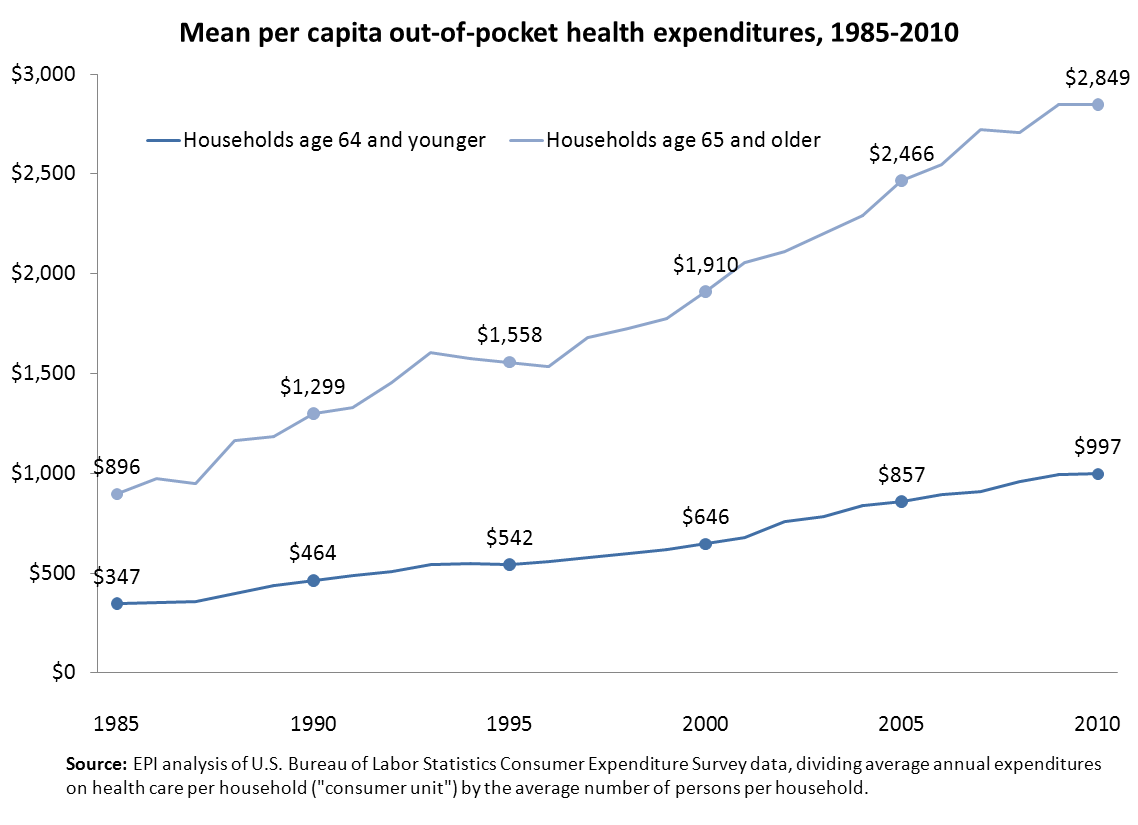

Seniors spend almost three times more on out-of-pocket health costs

Almost all seniors are covered by Medicare and most also have supplemental coverage. Nevertheless, out-of-pocket (OOP) health expenditures are higher for seniors than younger households because seniors tend to be in worse health. Though the weak economy and the 2006 Medicare prescription drug benefit have moderated growth in OOP spending, per capita costs are nearly three times higher for seniors than for younger households ($2,849 versus $997).

OOP costs have grown significantly faster than inflation over the past 25 years—at an average annual rate of 4.4 percent across all age groups (4.7 percent for seniors), compared to 2.7 percent annually for overall consumer price index (CPI-U) inflation. These figures are based on the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Expenditure Survey (CEX) and reflect faster growth in the price of medical goods and services as well as greater consumption and cost sharing.

Average per capita spending for seniors now consumes 20 percent of the average Social Security retiree benefit, up from 16 percent in 1985. These figures understate the financial burden posed by OOP health spending because CEX does not survey people in nursing homes. A Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) data found that long-term care constituted 19 percent of OOP health care spending for Medicare beneficiaries in 2006.

How much will the Ryan Medicare voucher cost you?

The supposedly kinder and gentler Medicare voucher proposed this year by House Budget Committee Chairman and Republican vice presidential nominee Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) is less draconian than last year’s version, but still packs a wallop. The voucher shifts costs to seniors because the value of the voucher can’t grow faster than half a percentage point above per capita GDP, and health care costs are projected to grow faster than that. (You can ignore the part about tying the voucher to the second-lowest-cost private plan or, if it’s cheaper, fee-for-service Medicare cost growth—this is just window dressing because overall costs will exceed the “fallback” spending limits.)

The voucher will initially shift around 11 percent of costs ($700) to seniors in 2023, an amount that will grow to 45 percent ($15,700) by 2087 (all figures are in 2012 dollars and rounded to the nearest $100). You can see how this adds up by summing the annual amounts in the table below over life expectancy in retirement. Thus, for example, a 40-year-old female who expects to retire at 65 in 2037 will live to about 2058, during which she will pay roughly $82,800 more for health care.Read more

Congress: Put emergency unemployment compensation in the continuing resolution

The emergency unemployment compensation (EUC) benefits that millions of Americans are receiving to help them survive a period of long-term joblessness will terminate on Dec. 31 under current law. If the modest but steady income EUC provides—averaging about $300 per week—is cut off, then families, communities, and businesses across the country will suffer. Jobless workers will struggle to pay their rent and utilities and will reduce spending on discretionary purchases of food, clothing, recreation, and entertainment. Businesses, in response, will hire fewer employees. If EUC is not extended through the end of 2013, the effects on the economy will be serious: Economic activity will be about $56 billion lower than it otherwise would have been1and about 430,000 jobs will be lost—at a time when every job is precious.

So far, I have heard nothing to indicate that policymakers in Washington are addressing this matter, even though Democratic and Republican leaders are about to close a deal on keeping the government running for the next six months. It would be disastrous for Congress and the president to let EUC expire. Continuing EUC has to be part of the continuing appropriations legislation that congressional leaders are negotiating right now, which will fund existing programs all across the government through March 2013 at current levels. Read more