Bush-era tax cuts remain the obstacle to fiscal sustainability

Earlier this week, the Congressional Budget Office released its Jan. 2012 Budget and Economic Outlook, which showed a sustainable fiscal outlook over the next decade provided Congress leaves the budget on autopilot. The current law baseline—the legislated status quo—depicts the budget deficit averaging only 1.5 percent of GDP over the next decade (fiscal years 2013-22), public debt peaking at 75.1 percent of GDP in FY2013, and the public debt-to-GDP ratio gradually falling to a more-than-sustainable 62.0 percent of GDP by FY2022. This picture is not perfect—the fiscal drag from the debt ceiling deal and expiring tax provisions is projected to slow growth to an anemic 1.1 percent of GDP in 2013 (and unemployment projections were raised half a percentage point across the decade)—but it is certainly fiscally sustainable in the out years, after the economy has recovered.

And the single biggest policy threat to this sustainable fiscal outlook? Congress might extend all the George W. Bush-era tax cuts over the next decade, to the tune of $4.4 trillion over a decade. That’s $3.8 trillion (-9.1 percent) in revenue loss and $657 billion (+15.5 percent) in additional debt service. Yes, deficit-financed tax cuts increase spending. CBO’s current law baseline projects cumulative budget deficits of $3.1 trillion, so continuing the Bush-era tax cuts would more than double the scope of fiscal stress. (These calculations assume that Congress will continue patching the alternative minimum tax and attribute a $1.1 trillion interaction between the policies to the Bush tax cuts, which pushed more households into the AMT, significantly increasing the cost of the AMT patch.) Measured differently, the hefty opportunity cost of the Bush-era tax cuts averages 1.9 percent of GDP in revenue loss and another 0.3 percent of GDP in increased interest spending over 10 years.

Under current law, the budget will begin running sustained primary surpluses (where revenue exceeds non-interest spending) starting in FY2015. If Congress patches the AMT, primary surpluses begin in 2017. If the Bush tax cuts are extended, the budget never reaches primary balance. (Primary balance is a common metric for sustainability: while it does not necessarily stabilize debt as a share of GDP—which depends on interest rates, outstanding debt levels, and GDP growth—it’s a decent approximation.)

The Bush tax cuts remain expensive, ineffective, and unfair, and permanently extending even a portion of them—which President Obama proposes to do for 98 percent of households—makes it difficult to adequately fund public investments, economic security programs, and national security spending. Congress and the public have to accept that the federal government must either collect significantly more revenue (above that projected under current law) or renege on commitments insuring that seniors, the poor, and the disabled are provided with health care and a degree of retirement security. Like it or not, we can’t afford the New Deal, the Great Society, and the Bush tax cuts.

On Wilson’s muddled defense of the top 1%

Last week, the Washington Post published an essay by James Q. Wilson that’s bound to generate controversy. While Wilson acknowledges rising income inequality, his analysis of the factors driving the trend is seriously flawed. Furthermore, he belittles the need to tax the rich more in order to help the poor or to address overall inequality.

Wilson rightly acknowledges the growth of income inequality and correctly notes:

“The mere existence of income inequality tells us little about what, if anything, should be done about it. First, we must answer some key questions. Who constitutes the prosperous and the poor? Why has inequality increased?”

It is after this point that his argument goes off track. While there is much to comment on, I will only address a few issues, starting with Wilson’s explanation of rising inequality. He writes, “Affluent people, compared with poor ones, tend to have greater education and spouses who work full time.” Wilson then suggests that if these are the drivers of inequality, then it is best not to do anything about the problem, since, in his words, “We could reduce income inequality by trying to curtail the financial returns of education and the number of women in the workforce—but who would want to do that?”

It is true that those at the top have more education and are more likely to have a working spouse, but this hardly explains the large increase in inequality over the last 30 years. Let’s start with the role education plays in growing wage inequality. Wilson points out that those with at least a college degree saw wage growth far greater than those lacking a high school degree. While Wilson cites the data incorrectly (he cites Bureau of Labor Statistics data on “hourly” wages when they are actually median weekly earnings of full-time workers, and he flips the genders for college-educated wages), his point holds true: Wages have risen more for the college-educated (increasing 20 percent for men and 33 percent for women) over the last three decades than for those lacking high school degrees (with the wages of these workers falling 31 percent for men and 9 percent for women).

However, these data essentially compare the top 30 percent or so to the bottom 10 percent. In terms of explaining the surge in wages for the top, his analysis mostly misses the mark. After all, what we really need to explain is why the top 1 percent of wage earners saw their annual wages rise by 131 percent from 1979 to 2010—and why the top tenth of the top 1 percent saw their wages grow 278 percent—while wages for the bottom 90 percent increased just 15 percent (see the graph below).

Moreover, noting someone’s education does not explain why their wages rose or fell. After all, the reason why CEO pay has exploded in the last few decades is not because most CEOs happen to have college degrees. Rather, it’s due to a self-serving system that ensures CEOs reap the fruits of their company’s rewards.

As for Wilson’s point on working spouses, I’ll leave it to him to prove that this is a major driving factor behind the trends starkly depicted in the graph above.

Another serious flaw in Wilson’s argument is his contention that the existence of some economic mobility somehow negates the need to be concerned about high and rising income inequality. He illustrates mobility by pointing out that within nine years one can rise from being a business school student to earning a big Wall Street salary and a hefty yearly bonus. While this is true enough, Wilson misses the point yet again; business school students have traditionally been upwardly mobile. Instead, what is useful to know is whether someone from a poor or lower-middle-income family has the same or better chance of attaining such a position than in an earlier generation. The answer is quite clear that mobility within one’s lifetime (the chance of becoming that Wall Street banker) is no greater now than in the past. Moreover, the earning potential of today’s young workers is more tightly linked to their parents’ income than before. The existence of some mobility (and some variability from year to year) does not lessen the concern about inequality. (Also, see Dean Baker’s critique of the mobility data Wilson uses.)

In short, Wilson’s dismissal of inequality based on who the rich are, and why inequality has grown, is not very persuasive. However, the most curious part of Wilson’s piece is his contention that taxation is not relevant to income inequality:

“Making the poor more economically mobile has nothing to do with taxing the rich and everything to do with finding and implementing ways to encourage parental marriage, teach the poor marketable skills and induce them to join the legitimate workforce. It is easy to suppose that raising taxes on the rich would provide more money to help the poor. But the problem facing the poor is not too little money, but too few skills and opportunities to advance themselves.”

Are federal workers overpaid?

The Congressional Budget Office released a report today claiming that “the federal government paid 16% more in total compensation than it would have if average compensation had been comparable with that in the private sector, after accounting for certain observable characteristics of workers.” Specifically, the report finds that average wages were roughly the same in both sectors, but that the value of benefits was almost 50 percent higher in the public sector (the overall difference comes to 16 percent because the bulk of compensation takes the form of wages).

CBO cautions, however, that “estimates of the costs of benefits are much more uncertain than its estimates of wages, primarily because the cost of defined-benefit pensions that will be paid in the future is more difficult to quantify and because less-detailed data are available about benefits than about wages.” This a serious understatement. In fact, the results appear to hinge entirely on the interest rate used to discount pension benefits, which isn’t even mentioned in the report.

Though the report itself provides no useful information about how the cost of particular benefits was estimated, a working paper by the same author indicates that CBO probably used a 5 percent rate of return to discount the value of future pension benefits (in other words, $105 in pension benefits next year is valued at $100 today). In practice, this means that if the rate of return on pension fund assets turns out to be higher than 5 percent, which is very likely, the present cost of funding future pension benefits will be lower than CBO estimated.

Where does the 5 percent discount rate come from? CBO based this on a 4 percent “risk-free” yield on Treasuries, with a little wiggle room to account for the fact that pension benefits aren’t quite risk-free (“federal pension obligations are not protected by the Constitution, and the pension obligations of private-sector employers are only partially covered by the Pension Benefits Guarantee Corporation”). If you’re wondering why the riskiness of pension benefits matters rather than the expected return on pension fund assets, that’s a very good question.

With compounding, using a nearly risk-free discount rate can double or even triple the cost of pensions compared to using expected returns on actual pension fund assets. Admittedly, expected returns are uncertain, and the uncertainty itself imposes an indirect cost on pension sponsors. But if you’re going to consider indirect costs like uncertainty, you should also factor in indirect advantages for employers, like reduced turnover.

The experts consulted by CBO for this report include my EPI colleague, Heidi Shierholz, as well as two researchers on the other end of the political spectrum, Andrew Biggs of the American Enterprise Institute and Jason Richwine of the Heritage Foundation (Biggs and Richwine were also consulted for the working paper). Though it’s nice that CBO considered a range of opinions, it’s a shame that Biggs, Richwine and others have been successful in convincing CBO and others to use low Treasury yields to estimate the cost of future pension benefits. A paper to be released next week by EPI also shows that Biggs and Richwine use highly unorthodox methods in comparing public- and private-sector pay. Among other things, they ignore enormous differences in educational attainment between teachers and private-sector workers.

It’s not time to cut back on extended unemployment insurance

Congress is debating whether to renew legislation that has extended unemployment insurance benefits for the long-term unemployed for up to 99 weeks (73 weeks of federal benefits beyond the regular 26 weeks of state-financed benefits). The decision should be consistent with the original decision to extend benefits, based on the condition of the economy and the likelihood that jobless workers will be able to find paid employment.

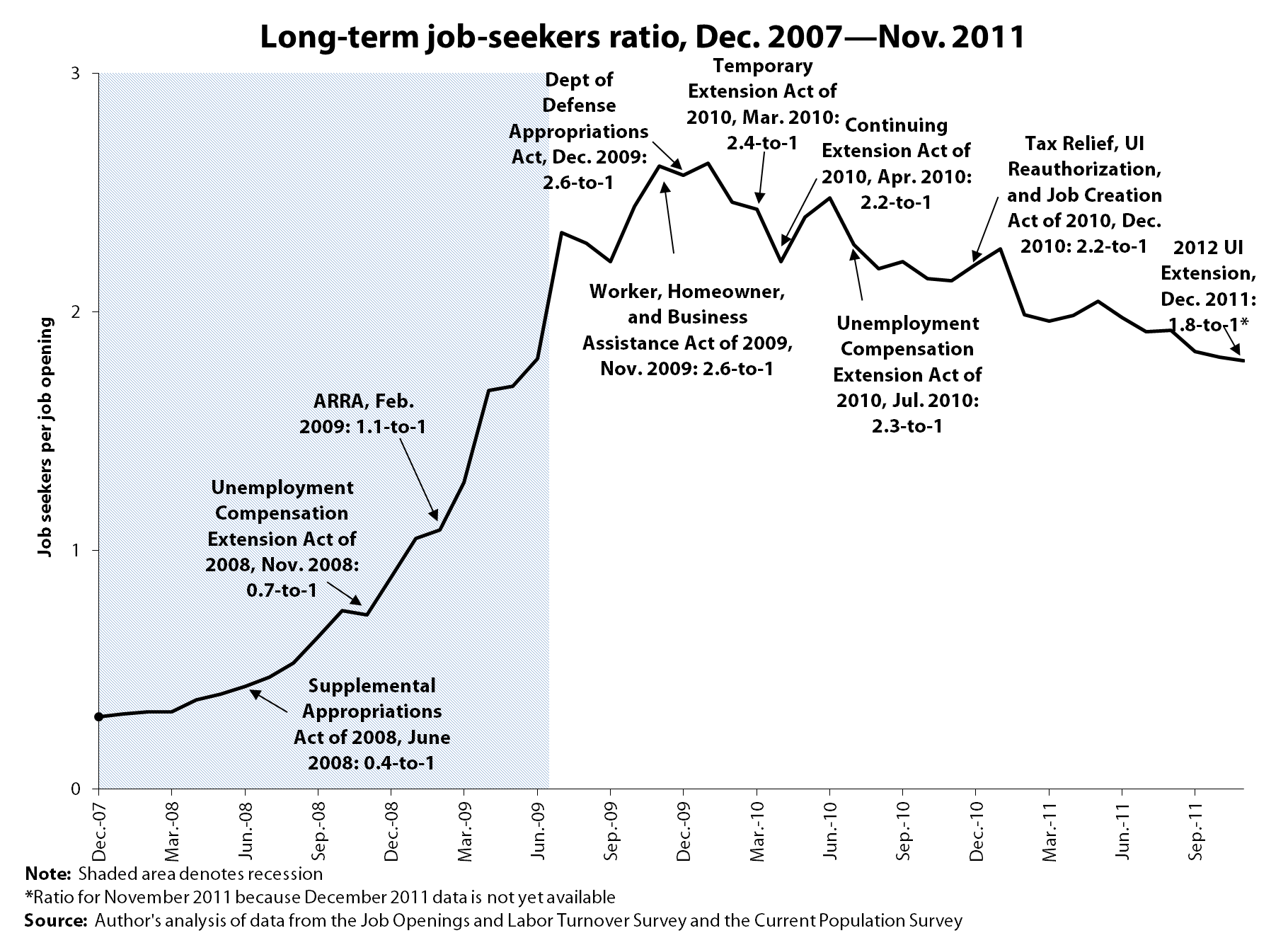

The unemployment rate, which was 8.3 percent in Feb. 2009 when the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) was enacted, and was 8.5 percent in Dec. 2011, is one measure, but not the best measure, of the need for extended benefits. The best measure is probably the ratio of long-term job seekers – the population that receives extended benefits – to available job openings. That ratio was 1.1 to 1 when ARRA put the 99 weeks of benefits in place and was still a much higher 1.8 to 1 in Nov. 2011.

This very high long-term job-seekers ratio indicates that the economy has not recovered enough yet to reduce the number of weeks of unemployment insurance benefits the jobless may receive. There are still more than 5.5 million Americans who have been seeking work for 27 weeks or more. Their ability to find work, to find employers willing to hire them after they have been unemployed for 6 months or a year, is greatly reduced.

Congress should reject Congressman Dave Camp’s (R-Mich.) legislation to eliminate 40 weeks of potential benefits or even 20 weeks, which some reports have mentioned as a compromise. Rep. Camp is off-base when he claims that 59 weeks of benefits is “a level consistent with prior recessions.” There has not been a single recession in the last 70 years that approached today’s levels of long-term joblessness. Both the number of long-term unemployed and the share of the unemployed who have been unemployed for more than 27 weeks are about double the levels of any other post-war recession.

Congress should renew the program of extended benefits as it is until the end of 2012.

Record low capacity utilization in electric sector inconsistent with “regulations kill jobs” mantra

The rate of capacity utilization in the electric utility sector dropped below 80 percent in 2011. This is the lowest level on record, with data going back to 1967, or nearly a half-century ago. The figure is far below the average utilization rate of 89 percent over this period. (See figure below.)

The exceptional degree to which there is unused capacity in the electric utility industry (or the “electric power generation, transmission, and distribution” sector as defined by Federal Reserve Board data) is entirely at odds with the notion that new regulations finalized or proposed by the Environmental Protection Agency are holding back job growth. To the contrary, this trend is consistent with the theory that such regulations can lead to modest increases in employment, since the compliance costs they lead to would not compete with other investments by this sector.

If regulation was holding back investment in the utility sector, one would expect there to be high capacity utilization rates. Companies would be relying heavily on existing capacity rather than investing in new capacity because they would be deploying investments on regulatory compliance, or because they were fearful new regulations would undercut their return on new investments.

While the existence of large, unused capacity is thus inconsistent with the notion that regulations are thwarting job creation in the electric utility industry, it is completely consistent with the notion that the lack of stronger demand is holding back increased investments in facilities or more hiring. Why make such investments when current resources are far from being fully utilized? The data suggest that until demand picks up more rapidly and cuts into excess supply, accelerated investments will not occur.

The broad attacks on regulation advanced over the past year have consistently featured the supposedly dire consequence of EPA regulations on the utility industry. The capacity utilization data for all of 2011 provide additional evidence that these attacks have been misplaced. Instead, the data are consistent with earlier EPI work finding that lack of demand, not regulations or regulatory uncertainty, underlie the modest pace of job growth and that now might be an especially timely moment to advance new regulations.

A minimum-wage increase in Illinois: Helping working families in the Land of Lincoln

The Illinois state legislature begins its next session this week and will likely debate a bill that will raise the state minimum wage from $8.25 to $10.65 over four years—providing a substantial boost to the state’s lowest-paid workers and the economy. The measure will mirror a similar proposal from last year, S.B. 1565, which would have raised the minimum wage in four steps and, after reaching $10.65, would have tied future increases to inflation. That measure would give 1.1 million low-wage workers a raise, providing more than $3.8 billion in increased wages for directly affected workers.

During the last 30 years, the real value of the Illinois minimum wage has eroded and working families’ incomes have essentially stagnated, reflecting the rest of the nation’s growing wage inequality. Restoring Illinois’ minimum wage to its pre-erosion level would help to return it to its original intent as a policy that sets wage standards for low-wage workers at a level that is high enough to be meaningful. Restoring the value of the minimum wage through incremental annual increases will ensure that it never again strays from its original purpose as a basic protection of fair wages.

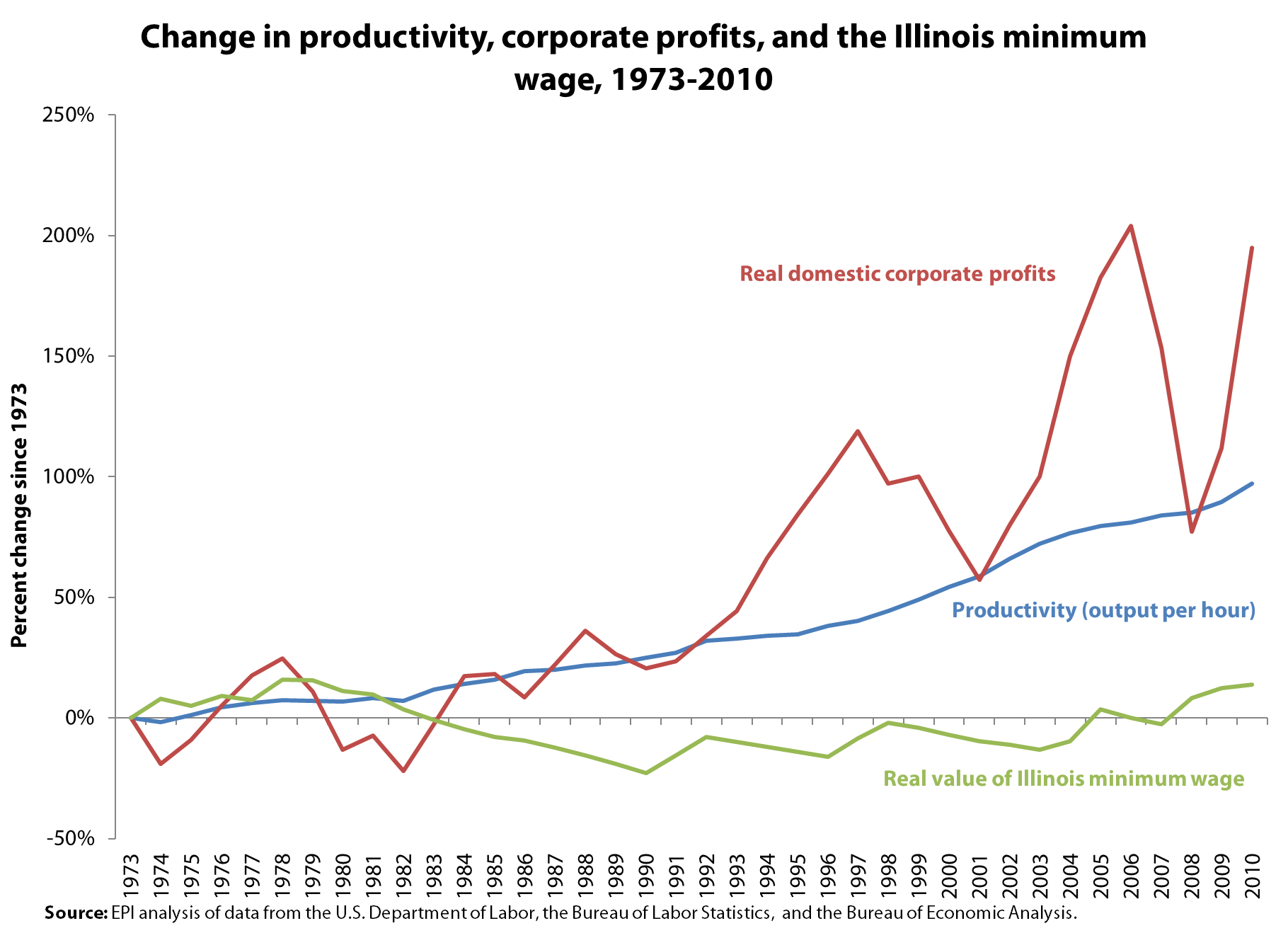

We know that a minimum-wage increase will boost the earnings of working families in Illinois—an added bonus is that it’s a tool for economic growth. It spurs spending by the workers who get the raise, thereby increasing economic activity and, in turn, creating jobs. It’s time that the American worker starts to share in the prosperity that corporate America has enjoyed—thanks to the growing productivity of workers—since the 1970s. A minimum-wage increase in Illinois would mean a shift from corporate profits to the America worker and would start to reverse the trend of increasing inequality evident since 1973. While corporate America enjoyed more than 200 percent growth in profits from 1973 to 2006, the real value of the Illinois minimum wage in 2010 was only 14 percent higher than it was in 1973. During the same period, American workers’ productivity increased almost 100 percent. The graph below shows this overwhelming disconnect:

Keeping the real value of the Illinois minimum wage at a level that allows low-wage workers to afford basic necessities is a policy that Illinois families cannot afford to lose—most minimum-wage workers are at least 20 years old and have total family incomes of less than $45,000. The consumer spending of workers affected by this increase will create a direct stimulus effect, pumping more than $2 billion into the economy and creating 20,000 jobs.

Amid persistently high unemployment (9.8 percent in Illinois), a resulting lack of wage growth, and a severe jobs deficit in Illinois, there will be no upward pressure on wages for a very long time. Since raising the minimum wage helps working families, does not cause job loss, and is a boost to the economy, now is exactly the time to increase the minimum wage.

Austerity’s effect on state job growth

David Leonhardt of the New York Times has a chart on the Economix blog today that shows how austerity measures at the federal, state, and local levels have held back growth in the U.S. economy over the past year and a half. As the blue line from his chart indicates, despite gains in the private sector, public sector growth was negative every quarter since Q3 2010.

What does this look like in terms of jobs? As you can guess, it isn’t pretty. In a blog post last September, I noted that government job losses are at the heart of overall job losses in numerous states since the recession officially ended in June 2009. Just to coincide with the timeframe I’ve noted from Leonhardt’s chart, the table below shows the change in government employment, total job losses for industries that lost jobs, and government losses as a percentage of total losses by state since Aug. 2010. The Dec. 2011 state unemployment rates and net change in employment figures are shown as well.

The numbers are pretty explicit: For the United States as a whole, every major industry except for government has gained jobs since Aug. 2010. Federal, state, and local governments have lost 440,000 jobs over that timeframe, accounting for 100 percent of losses for industries that lost jobs. Just to clarify, this does not mean that only government workers lost their jobs, but for every non-government worker in the country that lost a job over the past four months, at least one more job was created someplace else in that industry.

At the state level, government accounted for more than half of all job losses for industries that lost jobs since Aug. 2010 in 27 states, and made up 100 percent of losses for industries that lost jobs in Arizona, Idaho, Massachusetts, North Dakota, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Texas. Government losses also made up more than 50 percent of losses in seven of the 10 states with the largest number of jobs lost, and six of the 10 states with unemployment rates above 9.5 percent.

Of course, the private sector will absorb some of these losses and thankfully we have seen a positive net change in employment for most of these states since Aug. 2010. But make no mistake, the idea that drastic cuts to public budgets would somehow spur private-sector growth is a myth that has undermined recovery efforts both in the United States and in Europe. In reality, cuts to public-sector budgets have a significant negative private-sector impact. As my colleague Ethan Pollack has demonstrated, “for every dollar of budget cuts, over half the jobs and economic activity will be lost in the private sector.” Net change in employment since Aug. 2010 may be positive for most states, but it’s frustrating to think how much better these job numbers might be if we hadn’t spent the past 16 months shooting ourselves in the foot.

Research assistance by Natalie Sabadish

Massive tax cuts don’t square with professed concerns about public debt

The Washington Post editorial board astutely notes that the budget busting tax plans of the GOP presidential candidates contradict purported concerns about the budget deficit and national debt. Relative to the inadequate revenue levels collected by current tax policies, the tax plans would lose between $180 billion and $900 billion in 2015 alone—or between 1.0 percent and 4.9 percent of GDP. Former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney’s tax plan and former Pennsylvania Sen. Rick Santorum’s tax plans, respectively, represent the low and high end of this range, but former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich gives Santorum a run for his money with a tax plan that would lose $850 billion, or 4.6 percent of GDP, in 2015.

Under an extension of current policies, the budget deficit is projected to average around 4.3 percent of GDP over the next decade, which is unsustainable in the sense that debt as a share of the economy will continue to rise instead of stabilizing in the second half of the decade. Despite all the fear mongering rhetoric about Washington’s fiscal malfeasance heard from the GOP campaign trail, some of the candidates’ tax plans would more than double the budget deficit over the next decade.

The Post’s editorial board notes that the revenue loss estimates (calculated by the Tax Policy Center) are static scores, meaning that they don’t include growth effects (i.e., dynamic scores). Yet the growth legacy of the last round of deficit-financed, regressive tax cuts—the kind supply-siders love and the kind being floated on the campaign trail—proved a massive flop. This new round of massive tax cuts would either be deficit financed—trading public (di)savings for private savings—and/or financed with deep cuts to public investments and economic security programs, which would drag on growth (among other adverse economic outcomes). Mr. Santorum’s proposed balanced budget amendment, for instance, would force unfeasibly draconian spending cuts across the entire federal budget. His tax plan wouldn’t raise anywhere close to 18 percent of GDP, where he has proposed capping federal spending—current tax policies will raise only 17.6 percent of GDP over the next decade.

The distributional implications of these tax plans are just as concerning as their revenue impact and are amplified by their budgetary impact, which will force spending cuts that don’t show up in TPC’s distributional table. As the Post notes: “It makes no sense to further benefit the wealthiest taxpayers at a time when spending programs for the most vulnerable would be on the chopping block — of necessity, given the candidates’ pledges to cap spending. In their fiscal consequences these cuts would be disastrous; as a matter of fairness, even more so.”

Massive tax cuts don’t square with fiscal responsibility, as aptly demonstrated during the George W. Bush administration. Massive tax cuts targeted toward upper-income households will, however, exacerbate income inequality and undercut the middle class by defunding public investments and economic security programs. But the fiscal debate is not about the budget deficit, the public debt, or the middle class: It is about federal revenue and spending levels as a share of the economy, as epitomized by Grover Norquists’ Taxpayer Protection Pledge. Until conservatives reenter the realm of reality and acknowledge that revenue levels must go up, not down, fiscal responsibility and a sustainable trajectory for debt will remain unattainable.

Maybe Reagan was onto something…

Paul Krugman makes some good points about “post-modern” recessions (i.e., the last three, starting in 1990, 2001, and 2007, and which have all been followed by agonizingly slow recoveries) and then ends by asking, “And what about Reagan? Reagan who?” in making the point that very fast recovery following the 1981 recession was largely driven by monetary policy decisions.

This is mostly right, but, let’s look at the behavior of government spending following the last four recessions (i.e., the 1981 recession as well as the three “post-moderns”). The graph below measures real government spending relative to the previous business cycle peak.

So, 16 quarters after the start of the 1981 recession government spending was up nearly 19 percent relative to the pre-recession peak, while 16 quarters after the Great Recession of 2007, it’s up less than 1 percent. Let’s do some quick math. If we mimicked government spending growth from the 1981 recovery, government spending today would be about 18 percent higher than it was in the last quarter before the recession began – adding about $440 billion (in $2005) to overall GDP. This would lead to a roughly 3 percent boost to GDP and more than 3 million extra jobs not including any multiplier effects. Put a run-of-the-mill 1.4 multiplier on this and you have well over 4 million extra jobs – or roughly 40 percent of the entire “jobs gap” caused by the Great Recession that would now be filled.

Yeah, this is one thing about the 1981 recovery I’d like to replicate.

The Fed’s longer-run goals: Defining success down?

Yesterday, the Federal Reserve released a statement regarding its “longer-run goals and monetary policy strategy.” What seemed to the biggest news for most covering the release was the Fed’s identification of an explicit inflation target: 2 percent annualized growth in the personal consumption expenditures’ price index (oddly, they don’t specify just the “core” price index that removes more volatile items – not sure why).

This is pretty big news – and pretty bad news. While they leave themselves plenty of wiggle room to go above this target during particular circumstances, the economy could benefit greatly from an inflation target substantially above this 2 percent for the next several years, and it’s hard to see how yesterday’s statement makes this much easier. One could argue that by establishing a “long-run target” of 2 percent, the Fed could then justify shorter-term inflation targets above this level to make up for particularly disinflationary periods (like, say, the past four years), but again, the statement was pretty explicit about the 2 percent long-run target and not explicit at all about going above this in the near-term.

Bigger news, perhaps, was the statement’s identification of the “longer-run normal rate of unemployment” as being between 5.2 and 6 percent. This was always going to be the danger of a deep, drawn-out recession – policymakers will be tempted to declare “mission accomplished” well before unemployment has reached pre-recession levels (5 percent in Dec. 2007, 4.6 percent for the annual average of 2007), let alone before reaching levels that actually sparked widespread (and non-inflationary) wage-growth (the 4.1 percent average for 1999 and 2000, for example).

This is an old story – policymakers, particularly at the Fed, have for much of the past 30 years preemptively moved against higher rates of inflation by slowing the economy as unemployment has reached predetermined “longer-run normal” rates (the exact jargon and acronym for this magical rate that the economy allegedly cannot go below without sparking runaway inflation varies). Through much of the 1980s and early 1990s, economists more concerned with lower rates of unemployment than battling incipient inflation (sometimes called “inflation doves,” though I prefer “unemployment hawks”) argued that the Fed should at least test the limits of lower unemployment before short-circuiting recovery. And the late 1990s expansion proved them right – unemployment fell far below the contemporaneous estimates of the “longer-run normal rate” and yet inflation failed to accelerate.

Failing to heed this lesson and declaring that the best possible outcome that can be reached is an unemployment rate up to 1.5 percent higher (translating to three million extra unemployed workers) than what prevailed in the year before the Great Recession hit will just constitute one more severe casualty of this episode.

Discriminatory mortgage lending intensifies racial segregation

On December 21, Bank of America settled a Justice Department complaint alleging racial discrimination in mortgage lending by its Countrywide subsidiary. But underlying issues are far from resolved. Longstanding federal inaction in the face of widespread discriminatory mortgage lending practices helped create, and since has perpetuated, racially segregated, impoverished neighborhoods. This history of “law-sanctioned” racial segregation has had many damaging effects, including poor educational outcomes for minority children.

Bank of America’s Countrywide subsidiary was not alone in charging higher rates and fees on mortgages to minorities than to whites with similar characteristics, or in shifting minorities into subprime mortgages with terms so onerous that foreclosure and loss of homeownership were widespread. Racially discriminatory practices in mortgage lending (known as “reverse redlining”) were so systematic that top bank officials as well as federal and state regulators knew, or should have known, of their existence and taken remedial action.

Such complicity in racial discrimination by federal and state banking and thrift regulators is nothing new; in the past, they were complicit in “redlining”—the blanket denial of mortgages to minority homebuyers.

In the cases both of redlining and reverse redlining, regulatory failure has been destructive to the goal of a racially integrated society. Redlining contributed to racial segregation by keeping African Americans out of predominantly white neighborhoods; reverse redlining has probably had a similar result. Exploitative mortgage lending has led to an epidemic of foreclosures among African American and Hispanic homeowners, exacerbating racial segregation as displaced families relocate to more racially isolated neighborhoods or suffer homelessness.

The legal settlement requires Bank of America to spend $335 million to compensate victims of Countrywide’s discriminatory lending practices. This sum, while the largest fund to date for compensation of victims of discriminatory subprime lending, is still insufficient to restore their access to homeownership markets and to middle-class neighborhoods. In consequence, it will also do little to address the comparatively poor educational outcomes of children who are now more likely to grow up in racially segregated communities, nor the damage to learning that results when schooling has been disrupted by an unstable housing situation.

SNAPSHOT: Good credit didn’t protect Latino and black borrowers

State of the Union: Manufacturing a Better Future

In his State of the Union Speech last night, President Obama outlined a blueprint for rebuilding the economy the right way, by rebuilding American manufacturing, expanding clean energy investments and by fixing our broken infrastructure. Kudos to him for continuing to highlight this important issue, but he failed to mention the main cause of our manufacturing woes in the first place: currency manipulation.

First, some background. China currently engages in massive intervention in currency markets, buying U.S. dollar-denominated assets to boost the value of the dollar and keep their own currency artificially cheap. This acts as a subsidy to U.S. imports from China, and it raises the cost of U.S. exports — both to China and to every country where U.S. exports compete with goods coming from there. Of the nearly 6 million manufacturing jobs we lost between Jan. 2000 and Dec. 2009, 2.8 million jobs were displaced by growing trade deficits with China between 2001 and 2010.

Manufacturing employment is growing again, with 322,000 jobs added in the past two years. But millions of jobs have been left on the table. By ending currency manipulation with China and other Asian countries, we could create up to 2.25 million jobs over the next 18 to 24 months, boost GDP by up to $285.7 billion, and reduce the federal budget deficit by up to $857 billion over the next 10 years.

The president proposed some well-intended changes in tax policy designed to reduce incentives for manufacturing firms to outsource production abroad and to encourage them to bring jobs home. But tax policies only work around the margins of manufacturing employment. We need to go after root causes of manufacturing job loss such as currency manipulation by China and other Asian nations.

The Senate passed a bill last fall that would allow the Commerce department to penalize imports from China that have benefited from illegal currency manipulation. But House leaders will not allow the measure to come to a vote. The Obama administration has failed to do its part as well. Six times they have refused to identify China as a currency manipulator, denying the elephant in the room.

There are certainly other unfair trade practices beyond currency manipulation worth fighting. China provides illegal subsidies to domestic and foreign firms in a wide range of industries including steel, glass and paper. It also subsidizes clean and green technology industries, and maintains extensive barriers to imports of manufactured goods from the United States and other countries. The president announced important steps to create a new trade enforcement unit to bring together resources from across the government to attack unfair trade practices. This will allow the government to initiate new unfair trade cases against China and other unfair traders.

But with a gridlocked Congress held hostage by the Republican controlled House that has refused to compromise with the Senate or the administration, President Obama’s hands are tied on new initiatives that require congressional approval. Certainly, there is more that he could do to fight unfair trade, for example by confronting China over currency manipulation. But the administrative measures outlined in his SOTU address will begin to make a difference.

Mitch Daniels, deficit peacock

In issuing the Republican rebuttal to the State of the Union address, Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels had the audacity to present himself as a fiscal conservative and lecture President Obama on economic policy. Daniels presenting himself as a fiscal conservative is farcical: The tax cuts he pushed through for President George W. Bush as director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) are responsible for roughly half of today’s structural budget deficit and half the public debt accumulated last decade. And as expensive as they were, those tax cuts failed to spur even mediocre job growth; Daniels and Bush presided over the weakest economic expansion since World War II, leaving Daniels with a dismal legacy as an economic policymaker.

Daniels ran OMB from Jan. 2001 to June 2003; during his tenure, he helped craft the 2001 and 2003 Bush tax cuts. (Later tax acts accelerated implementation of some of these tax cuts, but this is when the real fiscal malfeasance occurred.) When Daniels took charge of OMB, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) was projecting a $5.0 trillion (4.0 percent of GDP) budget surplus over the next decade. When he left office, CBO was projecting a $1.4 trillion (-1.0 percent of GDP) budget deficit over the next decade. Roughly $4.8 trillion of the fiscal deterioration resulted from legislation enacted over 2001-2003; the tax cuts alone added $2.6 trillion to the public debt over 2001-2010. (The other major drivers of this fiscal deterioration were the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, which Daniels didn’t bother to pay for or even put on budget.) The 2001 recession certainly contributed to the emerging deficits—just as half of this year’s deficit can be chalked up to economic weakness—but the Bush administration’s economic policies ensured a mediocre economic recovery.

From Flickr Creative Commons by republicanconference

Though this supply-side snake oil was peddled as economic stimulus, the Bush-era tax cuts failed every test of good stimulus: They were gradually phased-in, they were targeted to upper-income households likely to save rather than spend, and they were intended to be permanent. Better economic policy could have alleviated the ensuing ‘jobless recovery.’

These tax cuts were the dominant economic policy during the worst economic expansion since World War II, measured by economic growth, employment, or compensation (trough-to-peak from 4Q2001 through 4Q2007). Real GDP growth averaged only 2.7 percent annually, the slowest of all the post-war expansions (averaging 4.8 percent economic growth annually). The economy only gained 97,000 jobs a month on average—not even enough to keep pace with population growth. (By contrast, job growth averaged 237,000 per month under President Clinton, when we had higher tax rates.) Real total employee compensation grew only 2.3 percent annually, contrasted with average annual compensation growth of 5.0 percent growth in post-war expansions.

Instead, the Bush tax cuts exacerbated inequality with a huge giveaway to those who didn’t need it: The top 1 percent of earners received 38 percent of the Bush tax cuts even though these households captured 65 percent of income gains during this expansion, leaving just scraps for the middle class. The Bush-era tax cuts can only be characterized as a costly economic policy failure.

Michael Linden of the Center for American Progress coined the phrase “deficit peacock” for self-purported deficit hawks interested in attention but uninterested in fiscal responsibility. Paraphrasing Linden’s birding guide, these deficit peacocks: 1) Never mention revenues; 2) Offer easy answers; 3) Support policies that make the long-term deficit problem worse; and 4) Think our budget woes appeared suddenly in January 2009. This summarizes Daniels to a tee. For him to lecture President Obama on fiscal responsibility is shameful.

Obama’s State of the Union speech sends the right signals

President Obama’s State of the Union address builds on his speech in Osawatomie, Kan. in December and that is a very good thing. That speech identified “whether this will be a country where working people can earn enough to raise a family, build a modest savings, own a home, and secure their retirement” as the key issue and argued against “you’re-on-your-own economics,” the economic perspective that says everyone should fend for themselves. We have increasingly followed such a vision over the last few decades and the results are clear, “fewer and fewer of the folks who contributed to the success of our economy actually benefitted from that success. Those at the very top grew wealthier from their incomes and investments than ever before.”

In contrast, the SOTU speech said, “We can either settle for a country where a shrinking number of people do really well, while a growing number of Americans barely get by. Or we can restore an economy where everyone gets a fair shot, everyone does their fair share, and everyone plays by the same set of rules.”

Obama pointed the way with a “blueprint for an economy that’s built to last – an economy built on American manufacturing, American energy, skills for American workers, and a renewal of American values.”

This is a much more encouraging policy vision than that offered by any of the president’s possible political opponents in the upcoming election; their policies are various versions of cutting taxes, especially on incomes obtained from wealth, redistributing the tax burden onto middle-class and low-income families and generating large permanent deficits. This is doubling down on the failed policies of the past.

Of course, whether Obama’s plan can lead to the desired results will depend on a political configuration that allows such policies to be legislated. It also depends on having a budget policy that actually delivers on the expanded public investments in innovation, education, infrastructure and manufacturing that are central to this strategy. That requires reversing the current course of budgets which imply major retrenchment of public investments over the next 10 years. The president’s establishment of the Buffett rule can help in this regard, especially since the SOTU clarified it as, “If you make more than $1 million a year, you should not pay less than 30 percent in taxes.” It would be stronger and more effective if we just taxed earned and unearned income at the same rate.

Last, as the president has noted at other moments, the typical working family has not benefited from productivity gains and economic growth over the last three decades. His pillars of growth (clean energy, infrastructure, innovation, education and skills) will strengthen productivity growth but do not directly address the need to reconnect pay and productivity growth. That requires low unemployment, a much higher minimum wage, better and actually enforced labor standards, and establishing in practice the ability of workers to conduct collective bargaining. It requires a trade policy (and exchange rate policies) that does not undercut our manufacturing sector. It requires the administration to stop its silly mantra of doubling exports and ignoring imports since the reality is that it is the ‘net’ of these two that affects growth and jobs. It requires building an economy where the financial sector is not dominant. And, that will require policies opposed by wealthy interests, a difficult trick in the age of Citizens United. That means we will need to weaken the impact of money in our democracy. There’s nothing easy about this path, but there is no alternative if we truly seek a democracy and an economy that work for everyone.

Apple execs (like everyone else) overlook global exchange rates

Charles Duhigg and Keith Bradsher have a justly buzzed-about article in the New York Times this week on how the production of the iPhone (and Apple products more generally) has become almost completely globalized. A quick but important addition to their story, though, is the role of exchange rates. Yes, I’m getting boring on this topic, but, exchange rates are by far the single most important determinant of U.S. trade performance, so if the question is “why isn’t X made in the US anymore,” it’s very likely that the answer remains “the dollar is overvalued.”

And, strikingly, even the Apple-specific timeline fits the data regarding the biggest exchange rate development – China’s mammoth intervention in international currency markets to keep their own currency from rising vis-à-vis the dollar. This is how Duhigg and Bradsher write it up:

“In its early days, Apple usually didn’t look beyond its own backyard for manufacturing solutions. A few years after Apple began building the Macintosh in 1983, for instance, Mr. Jobs bragged that it was “a machine that is made in America.” In 1990, while Mr. Jobs was running NeXT, which was eventually bought by Apple, the executive told a reporter that “I’m as proud of the factory as I am of the computer.” As late as 2002, top Apple executives occasionally drove two hours northeast of their headquarters to visit the company’s iMac plant in Elk Grove, Calif. But by 2004, Apple had largely turned to foreign manufacturing….”

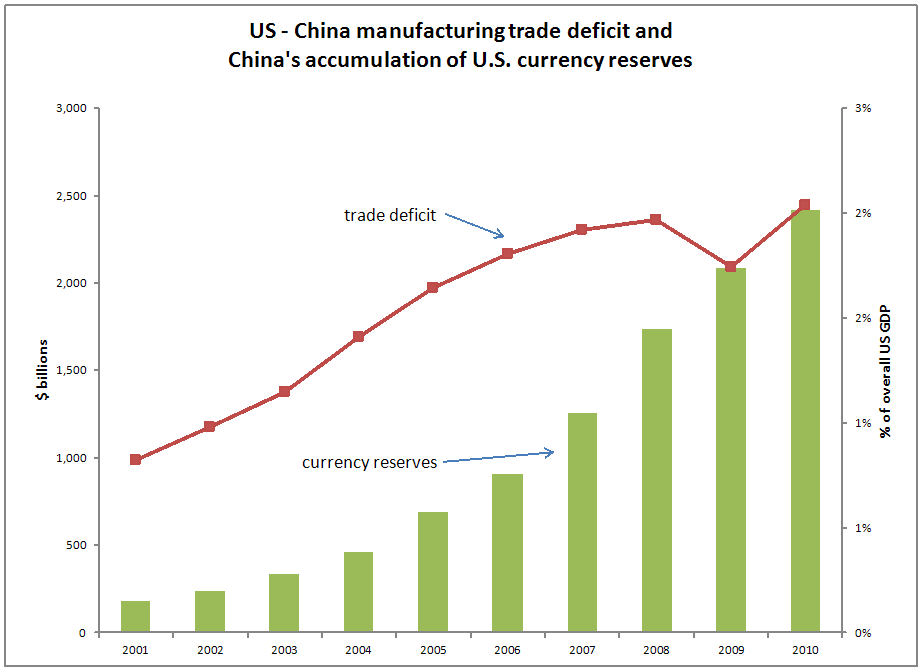

So, after 2002 Apple more and more turns to China for manufacturing? Huh. Not surprising – the graph below shows that the pace of Chinese accumulation of U.S. reserves (which leads inexorably to rising pressure on the dollar’s value, keeping Chinese products more competitive in U.S. and global markets) coincides with an accelerating increase in the U.S./China trade deficit around this time as well.

There is, after all, a reason why economists harp on the importance of the exchange rate – it drives lots and lots of hugely important economic decisions. As China intervenes to keep the value of its currency from rising against the dollar, this gives them an ever-increasing cost advantage versus the United States. The result is lots and lots of individual firm-level decisions (like Apple’s) to produce in China rather than the United States (because the exchange rate makes it cheaper) and the sum of these individual decisions cumulate to a huge aggregate trade deficit. The macro downsides of this trade deficit have been documented plenty of places, but if you’re writing about any feature of the US/China economic relationship and not mentioning this currency issue, you’re essentially writing Hamlet without the prince.

It’s frankly kind of amazing that Apple executives quoted in the article tell stories about how their global sourcing shifts are really about American skills, while managing to not mention global exchange rates. After all, there is an obvious trend in exchange rates and currency intervention that hamstring American competitiveness vis-à-vis China in the early-to-mid 2000s – but it’s awfully hard to make the case that American workers just got a lot dumber at the same time. But maybe blaming American workers can get some government subsidies for Apple to hire and train people in the U.S., while pointing out the effect of exchange rates might just lead to calls to rebalance the status quo U.S./China trade relationship – a status quo that has served Apple (and many other global manufacturers) very well.

A firewall has risen

It’s a pretty cool name for an otherwise drab concept. Yet, firewalls should matter to anyone who cares about government’s ability to promote economic growth, broadly shared prosperity, and social justice. Let’s start from the beginning, with the entire budget at $3.5 trillion (budget authority in 2011). Set aside mandatory programs—such as Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, unemployment insurance, and other social safety net programs—and interest payments. All told, that’s about $2.1 trillion of the budget, or two-thirds of the total. The remaining third of the budget is discretionary spending, about 58 percent of which is defense and war spending. The rest (the green slice) is everything else: homeland security, veterans benefits, roads and bridges, education, energy , health, and environmental research, consumer protection, law and order, community development… it’s all in there. This portion of the budget, which comprises a paltry 14 percent of the total, is referred to with the exciting name “non-defense discretionary.”

Because discretionary spending is appropriated each year, Congress can only cut it for the current or upcoming budget year. Instead, it can cap discretionary spending, as it did last August when it passed the Budget Control Act (BCA). These caps act as procedural obstacles to appropriating more than a specified amount in future years (also known as “out-years”). BCA institutes caps on the out-years, but only a single discretionary cap (excluding war spending). This worried progressives because it could allow conservatives in Congress to increase spending on the Department of Defense and pay for the increase with even further reductions in non-defense. In other words, it would provide conservatives with a double-win: They get to spend more on the Department of Defense even as the rest of the government faces cuts, and they get to use those defense increases to their advantage, to force even larger cuts to the non-defense budget than would otherwise be required if the entire discretionary budget were cut proportionately. This is where firewalls come in. Earlier this month, the Office of Management and Budget and the Congressional Budget Office each released an update on what happens next now that the Super Committee has failed. Most people have been focused on the sequestration provisions, which don’t take effect until 2013 (and will be heavily impacted by the election outcome). But, quietly, something else happened: As per the BCA law, automatic firewalls between defense and non-defense are now the law of the land. We should always be worried that conservatives will play the defense budget against the non-defense budget, but the new caps, which put separate limits on defense and non-defense, will make that eminently more difficult. And without further ado, here are your new budget caps!

And a little historical context…

Obviously, this isn’t exactly shared sacrifice. Non-defense discretionary, at 3.2 percent of GDP, is already below the 35-year average of 3.9 percent. Yet these caps cut this portion of the budget by almost $100 billion more than the defense budget, bringing it down to 2.5 percent of GDP, the lowest level in more than 35 years (as far as the budget authority data extends).

‘Reformers’ playbook on failing schools fails a fact check

Education “reformers” have a common playbook. First, assert without evidence that regular public schools are “failing” and that large numbers of regular (unionized) public school teachers are incompetent. Provide no documentation for this claim other than that the test score gap between minority and white children remains large. Then propose so-called reforms to address the unproven problem – charter schools to escape teacher unionization and the mechanistic use of student scores on low-quality and corrupted tests to identify teachers who should be fired.

The mantra has been endlessly repeated by Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, and by “reform” leaders like former Washington and New York schools chancellors Michelle Rhee and Joel Klein. Bill Gates’ foundation gives generous grants to school systems and private education advocates who adopt the analysis. In Chicago, Mayor Rahm Emmanuel makes the argument, and in New York, Mayor Michael Bloomberg has frequently sung the same tune.

And now, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo has joined in. On Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday last week, the governor cast attacks on unionized teachers as a defense of minority students against the adult bureaucracy. “It’s about the children,” Mr. Cuomo said. Because of failing public schools, “the great equalizer that was supposed to be the public education system can now be the great discriminator.”

But this applause line about school failure is an “urban myth.” The governor, mayor and other policymakers have neglected to check facts they assume to be true. As a result, they may be obsessed with the wrong challenges, while exacerbating real, but overlooked problems.

Careful examination discloses that disadvantaged students have made spectacular progress in the last generation, in regular public schools, with ordinary teachers. Not only have regular public schools not been “the great discriminator” – they continue to make remarkable gains for minority children at a time when our increasingly unequal social and economic systems seem determined to abandon them.

We have only one accurate performance measure. The government administers periodic reading and math tests to samples of fourth, eighth and 12th graders. Called the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP, pronounced “nape”), it is less subject to corruption than standardized tests now legally required of all schoolchildren.

NAEP samples are only large enough to produce reliable national and (for fourth and eighth graders) state estimates, but not for classrooms or schools. Thus, principals or teachers suffer no consequences for poor NAEP scores, giving them no incentive to steal time from instruction to drill on NAEP-type questions.

Not every selected student gets identical NAEP questions. Scores aggregate answers from different students’ booklets, covering different topics from the math and reading curriculums. In contrast, state and city standardized tests change little each year; teachers can predict which of many topics will likely appear, and focus instruction on those.

Here’s what NAEP shows: Average black fourth graders’ math performance in regular public schools has improved so much that it now exceeds average white performance as recently as 1992. The improvement has been greatest for the lowest achievers, those in the bottom 10 percent. Eighth graders show similar, though less dramatic trends. The black-white gap has narrowed little because whites have also improved.

These irrefutable facts characterize both the nation as a whole, and New York State specifically. In fact, New York State’s black children made enormous gains in the 1990s, and much slower gains once the federal No Child Left Behind, and Mayor Bloomberg’s and Chancellor Klein’s test-based reforms kicked in. From 1992 to 2003, for example, black fourth graders’ math performance jumped 22 scale points (about two-thirds of a standard deviation). From 2003 to 2011, the gain was only 5 scale points.

There is something perverse about using Dr. King’s birthday as the occasion for an accusation that schools have been the “great discriminators” when those schools have been boosting the achievement of African Americans at a far more rapid rate than they’ve been able to boost the achievement of whites.

Overall, the national and New York State data are hard to reconcile with a story that schools are filled with teachers having low expectations, poor training, and complacency arising from excessive job security, and the way to fix public schools is more accountability for student test scores.Read more

You can’t measure tax progressivity while ignoring income trends

Mark Thoma does a terrific job explaining why the purported measure of tax progressivity favored by many conservatives doesn’t measure tax progressivity. Former George W. Bush Press Secretary Ari Fleischer, the inspiration behind Thoma’s post, insinuated that those lucky duckies at the bottom and middle of the earnings distribution should be paying more because their share of federal taxes paid has been falling while that of the top earnings quintile has risen substantially since 1979. As Thoma elucidates, Fleischer’s captious reading of the Congressional Budget Office’s series on average federal taxes by income group ignores the heavily skewed income trends of the last 30-plus years.

This State of Working America chart depicts just how lopsided those gains have been: The top 10 percent have captured 64 percent of economy wide income gains, while the bottom 60 percent of earners received only 11 percent of income gains.

Data compiled by economists Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty show that this trend intensified during the Bush economic expansion, when the top 1 percent of households captured a stunning 65 percent of income gains, leaving just 13 percent for the bottom 90 percent of households. (The top 1 percent of households was simultaneously rewarded with 38 percent of the Bush-era tax cuts, when fully phased in.) These data don’t square with calls to shift the tax burden from capital to labor, and correspondingly from upper-income households to the middle class.

A progressive tax system embodies the principle that groups with more resources should pay a higher portion of their income in taxes than groups with fewer resources; taxes as a share of income—or effective tax rates—are intended to rise with income. Ignoring income necessitates disregarding this proper measure of tax progressivity. By Mr. Fleischer’s concept of tax fairness, Mitt Romney’s 15 percent preferential tax rate is a non-issue and there’s no need for a Buffett Rule. Similarly, ignoring effective tax rates is terribly convenient for conservatives attempting to shift the distribution of taxation down the income distribution, as proposed in many of the former and current GOP presidential candidates’ tax plans.

Without looking at taxes paid relative to income, one ignores ability to pay and progressivity, period. This may be politically expedient for those who want to abolish the Sixteenth Amendment and replace it with a regressive flat tax, but it’s intrinsically problematic when income inequality has returned to Gilded Age-levels. A greater degree of progressivity must be restored to the tax code, which must also raise more revenue for the realities of an aging population, spiraling health care costs, and a large structural budget deficit. Specious concepts of tax fairness cannot be condoned; they mask deep, growing inequities and provide cover for regressive tax plans that would further exacerbate income inequality.

Don’t blame the robots: It’s not productivity growth that’s holding job growth back

The Wall Street Journal ran an article a couple of days ago implicitly arguing that accelerating productivity growth is a prime reason why labor market recovery from the Great Recession has been so sluggish. Another reporter asked me about it yesterday, so I figured I’d write up a couple of thoughts on it.

First, we should be clear that the pace of labor market recovery since the Great Recession has not been uniquely bad; since the trough of the recession, private sector employment growth has actually been exactly in line with the (admittedly too-slow) recoveries from the recessions of the early 1990s and 2000s. Overall employment growth has actually outperformed the recovery from the early 2000s recession. Figure A below shows the trends for private sector employment. Note that the jobs lost during the latest recession dwarf those lost during other recessions – but since the official recovery began, job growth has been on-par with recent recoveries. Note that policymakers should not be graded on this generous curve – it’s a disaster that we haven’t had a better recovery from that perspective. But one doesn’t need to generate new theories to explain this allegedly atypically bad recovery – it just hasn’t been atypically bad.

Second, and in line with Dean Baker’s response to the article, productivity growth has not been particularly fast since the Great Recession. Figure B below shows the behavior of productivity averaged over all recessions between 1947 and 1981, the average of the early 1990s and early 2000s recoveries, and growth since the Great Recession. So, again, one cannot argue that fast productivity growth presents unique challenges in the current recovery since its performance just hasn’t been all that unique.

Lastly, and maybe wonkiest, fast productivity growth doesn’t change the validity of Keynesian diagnoses of what the economy needs at all. In fact, it would just strengthen them. The root of the Keynesian diagnosis is that there is a large gap between aggregate demand and potential supply in the economy – or, a large “output gap.” Figure C below shows the problem – the large output gap between actual and potential GDP is the reason why we have such high unemployment today. Productivity growth just pulls the potential GDP curve upwards, which means, all else equal, that the output gap will rise (on the chart I illustrated this with the “actual, if productivity growth accelerated” line).

But, the obvious solution to this problem is simply to push up demand to make actual GDP equal potential GDP again. Basically, accelerating productivity growth would just make measures to boost demand more necessary, and would insure that no adverse supply-side response (say accelerating inflation or rising interest rates) would kick-in.

The root cause of today’s underperforming economy remains insufficient spending by households, businesses and governments to fully employ all those who want a job. And the cure for this is simply policy measures to boost spending. Yes, I’m sure this has gotten boring for many economy watchers who want newer and more exciting diagnoses and cures, but sometimes what’s true is pretty boring.

One quick thought on why explanations based on productivity growth can sound convincing: At any point over the past century you could have walked into a factory and been told about the big technological improvements that had been made over the past four years. If you’re a business writer who walks into a factory today looking for a root cause of the labor market’s doldrums, guess what? You’ll be told about the big technological improvements made over the past four years, and then you might think, “hey, that’s why the jobs aren’t here!” But, if you had walked into a factory in 2000 – when the unemployment rate reached 3.8 percent – You also would’ve been told about an amazing four-year run of technological advance. In the end, high rates of unemployment are about demand falling short of supply, period.

Romney may not like government, but he loves its tax subsidies

Former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney has at long last revealed his tax rate, which he says is “probably closer to 15 percent than anything,” largely because his income “comes overwhelmingly from some investments made in the past, rather than ordinary income or earned annual income.”

Two points. One, generally speaking this isn’t a product of the ingenuity of Romney’s expensive tax accountants. Over the past 30 years, Congress has gradually lowered the top tax rate on capital gains from 40 percent in 1977 to the preferential rate of 15 percent today. In fact, the only significant increase in the capital gains tax rate in the last few decades was when it was paired with an even larger tax cut for high-income earners, a reduction in the top rate for ordinary income from 50 percent to 28 percent. (It should be noted, however, that Romney does benefit from the carried interest loophole, a defect in the tax code that allows private equity and hedge fund partners to reclassify their compensation as capital gains and thereby enjoy the 15 percent rate on all of their income, not just their capital income. But this loophole only exists because capital income enjoys a preferential tax rate in the first place.)

Second, this is a tax rate that most Americans would love to pay. According to the Tax Policy Center, an average family of four pays about 20 percent of its income in federal taxes (taking into account the employer-side payroll tax). This family’s tax rate will likely rise further if, as Romney’s tax plan calls for, the recent expansions of the EITC, the Child Tax Credit, and the Hope Credit (renamed the American Opportunity Tax Credit) are allowed to expire. Speaking of the Romney tax plan, 80 percent of its benefits would go to taxpayers like himself with income over $200,000—the same people that already disproportionately benefit from the preferential tax rate on capital income.

This gets to a more fundamental question: Why is the government favoring Romney’s income over that of most Americans? After all, it’s not like he’s been working recently—he’s been running for president for the better part of five years. And even if he did have the time to actively manage his investments, he’s not able to because they’re in a blind trust. As for the risk factor, sure he’s risking his capital, but he’s not bearing any more risk that most households in this economy face. So tell me again, why is it so important for the government to subsidize rich people like Romney at the expense of average American households?

The Gingrich nonsense

Newt Gingrich has been using the fast exchanges of the Republican presidential debates to ignore facts, misdiagnose economic problems and then present wrongheaded solutions. The key fact that he is ignoring is the Great Recession—the greatest economic downturn the country has seen since the depression of the 1930s. It is amazing that anyone could miss this fact, but, apparently, Gingrich has.

Once we acknowledge the existence of the Great Recession, Gingrich’s ideas stop making sense. His statement that “more people have been put on food stamps by Barack Obama than any president in American history” is ludicrous. The recession began in Dec. 2007; President Obama took office in Jan. 2009, more than a year later. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps) exists to reduce hunger in America. During this period of extreme economic hardship when the rate of hunger in America is high, our leaders should want the needy to turn to SNAP. Would a President Gingrich eliminate SNAP or prevent the number of SNAP recipients from rising during a recession?

Gingrich’s latest idea is to fire janitors in schools and “hire 30-some kids to work in the school for the price of one janitor, and those 30 kids would be a lot less likely to drop out.” It is true that teen (i.e., 16-to-19 years old) employment is correlated with positive student outcomes including high school graduation. But this is a horrible idea.

Think of a family where one parent is a janitor and one child is in high school. Gingrich is proposing to layoff the parent and replace the parent’s income with one-thirtieth the salary brought in by the child. Who knows how many hundreds of thousands of families would be plunged into poverty if this idea is ever implemented. We know that poorer children do worse in school, so any possible benefit from the increase in teen employment would likely be undone by the increase in poverty. One important reason that the teen unemployment rate is so high today is because of the Great Recession, the recession that began in the final year of the George W. Bush administration.

From Flickr Creative Commons by Gage Skidmore

It is great that Gingrich wants “to find ways to help poor people learn how to get a job, learn how to get a better job, and learn someday to own the job.” All Americans support these goals. But the real issue is this: What policies should we pursue right now to speed a full recovery from the Great Recession?

Gingrich wants to slash taxes. But we know that this is not the path to prosperity that Gingrich thinks it is. Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody’s Analytics, tells us that tax cuts are among the weakest things we could do to stimulate the economy and that increased SNAP spending is among the best. The reason is simple. People on SNAP are experiencing economic hardship. They spend their benefits, circulating those dollars in the economy. Much of the added income produced by tax cuts to people who are well-off is saved and not spent.

We also know to be skeptical of the tax-cut strategy because we tried it during the George W. Bush administration and it failed. President Bush cut taxes and “the U.S. economy experienced the worst economic expansion of the post-war era.”

Further, after examining the Gingrich Jobs plan, Howard Gleckman of the Tax Policy Center reports that “Newt Gingrich is proposing a massive tax cut aimed at the highest earning American households. Gingrich’s plan would add about $1 trillion to the federal deficit in a single year.” It is hard to imagine worse economic policy than Gingrich’s economic ideas.

Once we begin the discussion with acknowledgement that the Great Recession, which began more than a year before President Obama took office, is the root cause of the massive loss of jobs we’ve seen since 2007, we can see that Gingrich’s economic proposals are disastrous for the U.S. economy. Apparently, he wants hungry Americans to stay hungry. He wants to lay off workers and replace them with children making a tiny fraction of the prior wage. During this period of high unemployment, this policy guarantees an increase in poverty. And, while he has increased hardship and misery for the poorest Americans, he wants to make sure that the richest Americans get even richer with massive tax cuts. Gingrich’s vision for America is an American nightmare.

Krueger links progressive taxation, income inequality, and economic mobility

At a Center for American Progress (CAP) event yesterday, Alan Krueger, chair of the president’s Council of Economic Advisers, gave a presentation on the rise and consequences of inequality. As mentioned in a post by Ross Eisenbrey, Krueger dove into a lot of interesting statistics, many of which were compiled into a PowerPoint presentation, and many of which are also documented on our website.

One point in particular that merits highlighting is that the U.S. tax code isn’t terribly progressive compared to other OECD countries. This chart (Figure 10 in Krueger’s slideshow) shows the Gini coefficient – a measure of inequality – for OECD countries both before and after taxes and transfers. Contrary to conservative fears of the consequences of policies that promote any sort of redistribution, the U.S. tax code is actually uniquely modest in its attempt to reduce income inequality. As shown below, each of the tax codes of every OECD country save Turkey, Mexico, and Chile do a better job of promoting broadly shared prosperity than the U.S.

Krueger links this to the issue of income mobility—that is, the ability of people to move between income classes—which has been eroding over time. The graph he presents (below) shows the strong link between these two issues, showing that higher income inequality is associated with lower intergenerational mobility.

One of the fundamental tenets of the American Dream is opportunity and economic mobility, which have been moving in the wrong direction. As Krueger points out, one way to arrest this disturbing trend is by making the tax code more progressive. And as the first graph shows, we have a lot of room to improve.

Income inequality is a policy choice

In a speech today at the Center for American Progress, the Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors, Alan Krueger, laid out a compelling argument that rising inequality is a danger not just to the middle class, but to the recovery from the Great Recession and to the long-term growth of the U.S. economy. Krueger showed, with the help of some excellent charts, that the polarization in income in the U.S. has already shrunk the middle class dramatically and that the median household’s income is lower today than it was 10 years ago. Data from around the world support a connection between increased equality and increased economic growth and between income equality and economic mobility.

EPI has been sounding the alarm about the rise in inequality for many years, and a useful tool on our website shows the history of how national income has been shared between the bottom 90 percent and the top 10 percent, going back to 1917. As Krueger pointed out, the problem began in the late 1970s. From 1979 to 2008, income in the U.S. grew steadily – by an average of $10,401 per capita. But all of that income growth went to the top 10 percent, and the top 1 percent increased its annual income by more than $1.1 trillion. The nation grew substantially wealthier, yet the bottom 90 percent did not share in that increase at all – in fact, its income declined.

Krueger pointed to a number of contributing causes for this rising inequality, including globalization, which pits U.S. workers against a huge and more poorly paid labor force in the developing world, tax policy, the failure to increase the minimum wage, and a decline in unionization. We have no choice about whether our economy will be closely linked to the rest of the world, although we could manage the relationship better. But the other matters – tax policy, the minimum wage and unionization – are entirely within our control.

Tax policy should not advantage the rich, who have already taken a much bigger share of the national economic pie than they did when our economy was at its strongest and fairest. Krueger announced his adherence to the Buffet Rule, which holds that people making more than $1 million a year should not pay a lower share of their income in taxes than middle-class families. He recommended repealing unnecessary tax cuts for the wealthy and returning the estate tax to its 2009 levels.

Mitt Romney and President Obama both agree that the minimum wage should be raised, but they surely disagree about how to reverse the decline in unionization – or even whether it’s a bad thing. Krueger cited evidence that the primary effect of unions on the wage structure is to lift lower class families into the middle class. That is clearly a positive outcome, and efforts to weaken unions, through “right-to-work” laws like one being debated in Indiana, or federal legislation to make it harder to organize new unions, will worsen income inequality and should be opposed.

Inequality in America is worse than in all but a handful of developed countries; and it is getting worse fast. Krueger and the Obama administration are absolutely right to focus public attention on it.

Asking the wrong question about presidents and jobs

Ezra Klein asks a number of former chairs of the White House Council of Economic Advisors if presidents can create jobs. Since this allows me to channel one of the greatest Saturday Night Live skits ever, let me point out that the question is moot.

The right question is: Are the policies pushed by presidents or candidates appropriate to the economic problems and challenges actually facing the country?

So, was the Obama administration right to advocate for substantial fiscal support as soon as they entered office? Absolutely – the economy was losing around 750,000 jobs a month by the time they took the reins of policymaking, even as the Federal Reserve’s conventional recession-fighting tools were exhausted. Were they right in advocating for further substantial fiscal support this fall? Again, absolutely yes – the Fed’s recession-fighting tools remain ineffective even while unemployment hovered over 9 percent. The proper criticism of their actions is, of course, that they have not been aggressive enough in their advocacy for more fiscal support.

What does this mean for Mitt Romney’s job prescription to cut (spending and taxes) and deregulate? That it’s a fundamental misdiagnosis of what actually ails the U.S. economy. The mammoth job loss we experienced during the Great Recession didn’t occur because taxes went up or regulations proliferated in Dec. 2007 – the job-losses happened because spending by households and businesses collapsed in the face of the bursting housing bubble.

From Flickr Creative Commons by Secretary of Defense

Klein is right that many things besides presidential policy preferences and even policy actions determine job growth in the economy. But, this does not mean that they’re irrelevant to economic performance, and I fear far too many of Klein’s readers will come away from this column with the impression that they are; or even worse, that there’s little information available to voters to assess who would be the better economic manager. That’s not right – the president sets the agenda and it’s hugely important to know what this agenda is and whether or not it’s appropriate for the economic challenges facing us.

Klein’s also right that it would be nice if there was an easily-tracked single benchmark that reliably graded presidential performance, but that such a benchmark doesn’t exist. That said, answering the right question – are candidates proposing solutions consistent with the problems – isn’t really so hard.

Trade and jobs – why make it so hard?

Sometimes it seems like policymakers think that points are given for degree of difficulty. The Washington Post reports a number of policies are being considered by the Obama administration to “reward companies that choose to bring jobs home” and eliminate tax breaks “for companies that are moving jobs overseas.”

The impulse behind these ideas seems fine to me – the U.S. economy continues to “leak” too much demand to the rest of the world in the form of chronic trade deficits.

But, as the article notes, designing tax-based solutions to this problem will be quite complex and would take huge amounts of money to actually move the dial on this problem.*

If only there was a policy solution that was simple, could happen even without a gridlocked Congress, and would actually move the dial on the problem of large trade deficits dragging on growth.

But there is! Allow the dollar to fall in value sufficiently to move the trade deficit much closer to balance. Currently the biggest impediment to this happening is the policy of major U.S. trading partners (China is the linchpin) of managing the value of their currency to keep it from rising against the dollar – this results in Chinese exports gaining cost-advantages in both the U.S. and third-country markets where Chinese-produced goods compete against U.S.-produced ones.

Presumably this issue came up in Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner’s meeting with Chinese leaders yesterday, but this issue has “come up” between the U.S. and China for a decade with no movement. As Joe Gagnon and Gary Hufbauer have pointed out, however, there is no need to wait for China on this one – the U.S. could solve this currency management unilaterally.

Engineering a decline in the dollar’s value costs taxpayers nothing, can be done without moving through a gridlocked Congress, would actually provide significant help to the job market in coming years, and requires no Byzantine redesign of the tax code.

So, yes, one probably shouldn’t bet on it happening.

*Yes, there are ways that features of the U.S. tax code provide some incentive for production abroad rather than at home – and these should be removed. But this is surely a second- or even third-order driver of trade flows, at best.