CBO, CRS, EPI find toxics and other EPA rules have benign economic effects

A growing body of research is finding that new Environmental Protection Agency rules will not disrupt the economy and may in fact modestly boost employment. According to a new report by EPI and a January report by the Congressional Research Service, this is true for the air toxics rule, the most costly regulation finalized by EPA during the Obama administration. More generally, overlooked testimony by the director of the Congressional Budget Office from last November concludes that efforts to derail air quality regulations generally, if successful, would harm the economy.

On Dec. 16, 2011, EPA issued its final standards for mercury, arsenic, and other toxic air pollutants from power plants (the “toxics rule” or the “Utility MACT”). In January, CRS issued EPA’s Utility MACT: Will the Lights Go Out? As the title suggests, the report’s main focus is on whether the rule would, as some claim, affect the reliability of the power supply. CRS found otherwise, noting that while some facilities would be retired, “almost all of the capacity reduction will occur in areas that have substantial reserve margins,” meaning that the reductions can be easily absorbed without affecting power supply. CRS also observed that the rule includes additional time for compliance if in fact reliability is threatened in specific areas. The report’s bottom line conclusion: “…It is unlikely that electric reliability will be harmed by the rule.”

Last week, my colleague Josh Bivens released a report on the employment effects of the toxics rule. His analysis, unique in its comprehensive examination of both the positive and negative ways in which a regulation can influence employment, concluded that: “The toxics rule will lead to modest job growth in the near term and have no measurable job impact in the longer term.” His preferred single estimate is that 117,000 net jobs would be created.

The main reason why jobs would be created on balance in the near term is that the jobs generated by complying with the regulation, through pollution abatement activities such as increased investment on and the installation of scrubbers, will substantially exceed any jobs lost because of the modest increase in the price of electricity that would be produced. As Josh explains in his report and elsewhere, this is especially true today because of the large amount of capital and labor that is sitting on the sidelines; regulatory changes that spur investments to bring power plants into compliance with the new rules will mobilize this unused capital without leading to any offsetting rise in interest rates.

The Congressional Budget Office uses similar economic logic in assessing air toxics and other air quality rules. In testimony before the Senate Budget Committee on Nov. 15, 2011, CBO director Douglas W. Elmendorf included a general assessment of how initiatives to block EPA air quality rules would affect employment or output. He concluded: “On balance, CBO expects that delaying or eliminating those [EPA air] regulations regarding emissions would reduce investment and output during the next few years,” [emphasis added]. Essentially, CBO argued that the jobs created through investments to comply with the rules would exceed the number of jobs created due to alternative investments in the absence of the rules, because little such alternative investing would likely occur. (In my view, this reflects the fact that capacity utilization in the utility sector is at the lowest level on record, suggesting no need for further investments.) CBO also pointed out that the price increases that may result from these rules will not occur for several years, mitigating any near-term impact.

CBO’s use of the argument that regulatory changes are especially likely to spur job gains when, as is the case today, the economy has substantial slack in labor and capital markets, confirms that this reasoning is firmly based in mainstream economic analysis. It is an important argument that deserves greater attention in the ongoing regulatory debate.

Congress’ arbitrary ‘compromise’ on UI benefits

It’s good to hear that Congress has reached a deal to extend the payroll tax cut and long-term unemployment benefits.The tax relief to working families and the stimulus provided by unemployment payments is critical to protecting some of the recent improvements we’ve seen in the labor market.

But the nature of the “compromise” that congressional negotiators reached with regard to the length of unemployment benefits seems shockingly arbitrary. According to The New York Times, congressional Republicans wanted to end unemployment benefits after 59 weeks, while congressional Democrats pressed for coverage up to 93 weeks. They ultimately settled on a maximum of 73 weeks.I suppose given the state of Congress, we should be happy they could compromise on anything; but is this “let’s just meet near the middle” approach really the best way to decide when to end important social protections?

The point of unemployment insurance is, of course, to provide some level of income to workers during periods of joblessness. On a macro level, it also helps to counter economic downturns by mitigating the drop in consumer spending that inevitably occurs during periods of high unemployment.Thus, as Peter Orzag recently argued, if policies like unemployment insurance and payroll tax cuts are designed both to protect individual workers and the larger economy during times of distress, why would we want to affix them to arbitrary endpoints rather than overall economic conditions?Wouldn’t it be better to let the unemployment rate or even the long-term unemployment rate dictate how long we provide this additional economic support?

Roughly 2.3 million Americans, or 17 percent of the unemployed, have been searching for a job for at least 73 weeks – not including those that have given up looking for work and have exited the labor force. I should note that this is not the number of people who will lose benefits under the new proposal.Because each state has different unemployment eligibility requirements, differing lengths of state-sponsored coverage, and because federal support is also linked to state unemployment rates, it’s difficult to quickly estimate just how many will lose their benefits under this new cutoff.There are about 400,000 people who have been unemployed between 73 and 99 weeks, the existing cutoff point for unemployment benefits, but not all of these people have been collecting benefits.

Some will argue, of course, that cutting off unemployment benefits will spur some job seekers to redouble their efforts, as if it’s their lack of trying that is keeping them unemployed.I think the table below suggests otherwise.It shows the 20 states with the highest number of individuals unemployed for at least 73 weeks as a share of their states’ labor force.The cells highlighted in blue denote the top 10 values in each column.

As one might expect, the states with the highest unemployment rates are also states with the highest proportions of these “73-weekers.” In other words, in places with the highest proportions of long-term unemployed, it’s really hard to find a job. As Heidi Shierholz explains in greater detail, the reason so many have struggled to find work for so long isn’t because they are lazy or that they don’t have the proper skills, but that there simply aren’t enough jobs.The most recent Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) indicated 3.9 job-seekers for every posted job opening nationwide in December.

Unfortunately, JOLTS does not include state-level statistics, but I would comfortably wager that this ratio is even more extreme in places like Nevada and Florida.Congress should be focused on doing everything it can to stimulate job growth in these states, not negotiating some arbitrary line for when job seekers there will suddenly be without help.

The president’s jobs package would indeed create jobs

One of the best aspects of President Obama’s new budget plan is its near-term focus on job creation. This is a significant change from last year’s budget, where job creation was effectively ignored in favor of deficit reduction (likely in response to the GOP victory in the 2010 midterm elections, but that’s no excuse). This year, the president included $350 billion in job creation, $300 billion of which would hit the economy in the next year and a half. Here’s what’s in it though fiscal year 2013:

- $95 billion in the payroll tax cuts (employee-side)

- $80 billion in other business tax cuts (including a $25 billion hiring credit)

- $45 billion in emergency unemployment benefit extension

- $25 billion in transportation infrastructure investments ($50 billion over ten years)

- $20 billion in school facility repair and modernization

- $30 billion in retaining or rehiring teachers and first responders

- $25 billion miscellaneous neighborhood stabilization, job training, energy efficiency, VA conservation jobs, infrastructure bank, and manufacturing incentives

Last fall, the president proposed the American Jobs Act (AJA), a collection of policies designed to jump-start the economy. There are a few differences between the AJA and this jobs package—some policies were already enacted, some were scaled down, and there are a few new proposals—but this is essentially an updated and revised AJA.

And like the AJA, this jobs package would have an immediate positive impact on the economy and jobs. About 85 percent ($300 billion) of the package would hit the economy in the next year and a half. Using standard macroeconomic multipliers for the various policy categories, we find that the president’s job creation proposals would create 1.5 million jobs in fiscal year 2012 and 1.3 million jobs in fiscal year 2013 (through Sept. 2013).

The following graph shows by how much this proposal would lower unemployment relative to the unemployment levels under the Congressional Budget Office’s economic projections, if the historical relationship between GDP growth and unemployment held over the next two years. Note that CBO assumes that in Jan. 2013 the entirety of the Bush tax cuts will expire and the sequestration trigger will be implemented in full. A more realistic policy assumption that at least partially extends the Bush tax cuts and replaces the trigger would lower their projected unemployment levels. However, because the unemployment path under the jobs package was constructed off of the CBO baseline, the gap between the two would remain the same.

Some might argue that the full value of the $300 billion in the next year and half should not be included as “new” fiscal support, since the payroll tax cut is very likely to be extended for the full year (and full-year extension is included in the baseline of most macroeconomic forecasters’ models). In addition, the unemployment insurance extensions are also likely (though not guaranteed) to also run through all of 2012 (and many forecasts have some portion of these included in their baseline as well). Still, given the intense political pressure to move to immediate fiscal tightening, we think even just preserving the fiscal support already included in many forecast baselines is an important step in the president’s budget and should be highlighted.

For more on our job creation methodology, see our memo from last fall.

Morals, money and book promotion

Since an unexpected link from Noam Chomsky (whoa!) has brought it some attention, I may as well take the chance to introduce my book Failure by Design as a piece of evidence in the “morals versus money” debate going on.

David Brooks, channeling Charles Murray, argues that moral/social decay led to the poor economic performance in the bottom half of the income distribution in recent decades. Paul Krugman, Dean Baker, and Larry Mishel (I’m sure I’m missing others) demur – arguing that evidence for the poor economic performance is clear as day while evidence pointing to moral/social decay as an independent cause is awfully unpersuasive. (Wait! Don’t choose sides already based purely on teams – I have more evidence to offer!)

One thing that hasn’t been mentioned yet is that there’s plenty of reason to believe that things besides moral/social decay led to poor economic performance; policy changes alone just about guaranteed this poor performance. As Failure by Design notes, recent decades have seen: the inflation-adjusted value of the minimum wage fall for years (almost decades) at a stretch (leaving it still today below its late 1960s peak); an ongoing decline in the share of workers represented by a union (even while the share of workers desiring a union has not much moved); a much-larger share of the total U.S. economy accounted for by trade with much-poorer nations; and a Federal Reserve that has been less and less willing to push back hard against unemployment rates that rise above even their own conservative targets.

Nobody, absolutely nobody, disputes that these things should’ve been expected to do anything but inflict disproportionate harm on low- and moderate-wage workers. The conservative case for making these policy changes was that they would improve overall economic performance and if one was so inclined to make sure that low- and moderate-income workers were not harmed by these policy changes, one could have used the tax/transfer system to redistribute some of these overall gains their way.

I’d complain that not enough of these overall gains have found their way to the bottom half of the income distribution – but it’s awfully hard to believe these overall gains happened at all. Measures of aggregate economic performance are really no better (and are mostly worse) in recent decades even as incomes are shifted.

Bad Apple labor practices: Promises have been made before

The New York Times‘ brilliant two-part investigation of the wretched treatment of Apple’s manufacturing workforce is the obvious cause of the announcement that Apple is submitting to outside monitoring of conditions in its suppliers’ factories. No one at Apple headquarters had a religious epiphany; they were disgraced in the pages of the world’s greatest newspaper, and the public was beginning to react. This is not to say that a public relations gambit can’t lead to real change. But Steven Greenhouse’s story in the Times yesterday raises fair questions about the depth of Apple’s new commitment to labor rights.

Apple had two obvious choices for outside monitor: the Fair Labor Association, a monitoring group funded by the corporations it monitors, or a truly independent organization like the Worker Rights Consortium, which does not accept contributions from any for-profit corporation, let alone the corporations it monitors. The fact that it chose the in-house alternative tells me that Apple is less than fully committed to its new cause.

It’s worth noting that Apple has gone down this route before, with lousy results. In 2007, after China Labor Watch and Chinese journalists reported serious abuses at Apple’s key supplier, Foxconn, Apple hired Verite to monitor Foxconn’s labor law compliance. Foxconn is the company where—three years after Verite was hired—workers began committing suicide to escape their servitude, inhumanly crowded conditions, and personal abuse.

There are other reasons to doubt that anything material will change. The Fair Labor Association’s Executive Director, Jorge Perez-Lopez, with whom I worked at the Department of Labor, is a very decent guy. But when he says Apple will have no influence on which factories will be inspected or when, it’s hard to believe, especially when Apple’s CEO made the announcement that the first inspections would be in Foxconn factories in Shenzen and Chengdu. Oops! What Mr. Perez-Lopez didn’t say is equally interesting: How will the findings be released? We have seen that public shame is a powerful motivator. Will Apple have any control over the timing or content of the monitor’s reports on conditions?

And most important, will the Fair Labor Association be allowed to investigate the causes of the poor conditions, which include the price Apple is willing to pay for its products? Apple, like Wal-Mart, is famous for squeezing its suppliers, leaving them less and less to pass down to the workers in wages. Scott Nova, Executive Director of the Worker Rights Consortium, estimates that Apple could triple the wages its suppliers pay and reduce its gigantic profits by only 7 percent. That might be the fastest and surest way to improve the lives of its 700,000 workers. But it wasn’t part of Monday’s announcement.

Labor Department tackles guest worker problems

On Friday, Feb. 10, the Department of Labor (DOL) announced a new set of rules for the H-2B program, the country’s main temporary foreign labor program for less-skilled workers in non-agricultural positions. The new rules are set to become effective in late April, and as the New York Times reported on Saturday, “the changes were hailed by advocates for guest workers, who said they would make it more difficult for businesses to exploit vulnerable foreign migrants and hire them to undercut Americans.”

I join in the applause for the H-2B rule changes. For several years, the H-2B program has operated in ways that defy common sense. For example, in the District of Columbia, where more than 30,000 people were unemployed in 2010 and the unemployment rate hovered around 10 percent, common sense tells you that hotels should have an easy time finding local residents to take jobs as maids or cooks. And if they really couldn’t find anyone from D.C. to clean hotel rooms, surely they’d find qualified applicants in Northern Virginia or Maryland.

Yet lodging giant Marriott Hotels claimed they couldn’t find anyone here or elsewhere in the United States for 48 hotel maid and cook positions. They got government approval to bring 48 H-2B workers from abroad to do work that local people (with a high school education or less) could have been trained to do very quickly.

How did Marriott do it? How did they convince the DOL that no one in the D.C. area was interested in and qualified for these jobs? One possibility is that Marriott might have dishonestly claimed that they tried to recruit U.S. workers but failed. Under the old program rules, DOL didn’t have to check the accuracy of Marriott’s claims; DOL in all likelihood simply accepted Marriott’s “attestation,” i.e., simply took their word for it. Widespread fraud and abuse, documented by government and news reports and legal cases, are the main reason DOL has done away with the attestation procedure in its new rule.

More likely, Marriott fully complied with the minimal recruiting requirements mandated by the current rules, and few qualified local residents responded, because few ever heard there were positions open and because the wages offered were well below the prevailing wage in the D.C. area.

Marriott offered to pay the cooks $9.80 an hour. Here are the median, mean (or average), and annual wages paid to cooks in D.C. in 2010. Marriott’s wage offer was $3.80 an hour less than the average paid to the lowest paid of the hotel, cafeteria, or restaurant cook occupations in D.C.

|

Marriott offered to pay the maids $8.50 an hour, even though the median wage for maids in D.C. was $14.58 and the mean was $14.44. Marriott’s offered wage was only 59 percent of the prevailing wage for maids in D.C. That might have been enough all by itself to discourage anyone in D.C. from applying for the jobs. It’s likely, however, that potential hotel maids in D.C. either didn’t see Marriott’s ad if it ran only for the required minimum of three days in some local paper, or if they did see it, it could have been months before the position was available and therefore job seekers ignored it.

|

If Marriott had been looking to employ cooks and maids in the broader, D.C.-Virginia-Maryland-West Virginia area, the prevailing wage would have been somewhat lower but still far above what the company actually offered.

|

It’s easy to see why employers like Marriott love the current H-2B program. They can legally pay temporary foreign workers less than the local market rate for essential jobs. Fixing this aspect of the H-2B program was the impetus for an earlier rule proposed by DOL, but that common sense rule was blocked by Congress after a lobbying firestorm. Employers claimed they’d go out of business if they were forced to pay the local average wage to maids and cooks (and especially landscapers), even though the employers they compete with are doing just that. But the fact that employers don’t have to document and prove their efforts to recruit U.S. workers—even at the below-average wages permitted by the H-2B program—exacerbates the problem and allows employers to ignore the employment needs of the local workforce where they do business, at the expense of the local workers’ ability to earn a living wage.

The new H-2B rules will help local workers find jobs at the prevailing wage for the work that they do. They will help put more unemployed Americans back to work, and also prevent the undercutting of employers who pay a living wage. Unfortunately, H-2B employers are already up in arms about these common sense reforms. Congress should not allow the desire of H-2B employers to lower American wages trump the need of unemployed workers to earn a decent wage.

Exports and growth: Running harder and falling behind

In his 2010 State of the Union address, President Obama pledged to double exports over the next five years, which would “support two million jobs.” How’s that working out? Not so well, despite claims to the contrary from the White House. In this year’s SOTU address, the president pointed to newly signed Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with South Korea, Colombia and Panama as policies that will generate more exports, and they are, but the U.S trade deficit with those countries also increased last year. In short, it’s hard to argue that the Obama administration has taken any serious steps to make trade flows move from a minus to a plus in generating growth and employment in coming years.

Their rhetoric often suggests otherwise. Just last week, Deputy National Security Advisor for International Economic Affairs Michael Froman claimed that “last year our exports of goods alone to China exceeded $100 billion, and have been growing almost twice as fast as our exports to the rest of the world.” While this was a nice welcome for China’s Vice President Xi Jinping, who visits the White House today, it turns out that this nice round (and arbitrary number) was only reached if one is willing to overlook some key issues in trade data.

On the broader question of export growth, while exports to China and the world have been growing rapidly, the volume of U.S. imports increased much more rapidly – and this means that U.S. trade deficits with China and the world have increased rapidly over the past two years. This increasing trade deficit has generated a net loss in trade-related jobs with both China and the world as a whole. Thus, while export growth may have supported some new U.S. jobs, the growth in imports has displaced a much larger number of jobs. Between 2008 and 2010, the growth of U.S. trade deficits with China alone resulted in the loss of 453,100 U.S. jobs. A thorough jobs analysis of U.S. trade in the 2009-2011 period has not yet been completed. However, the U.S. trade deficit in non-oil manufactured goods, the most labor intensive portion of U.S. goods trade, increased by $129.3 billion in this period, displacing hundreds of thousands of U.S. manufacturing jobs.

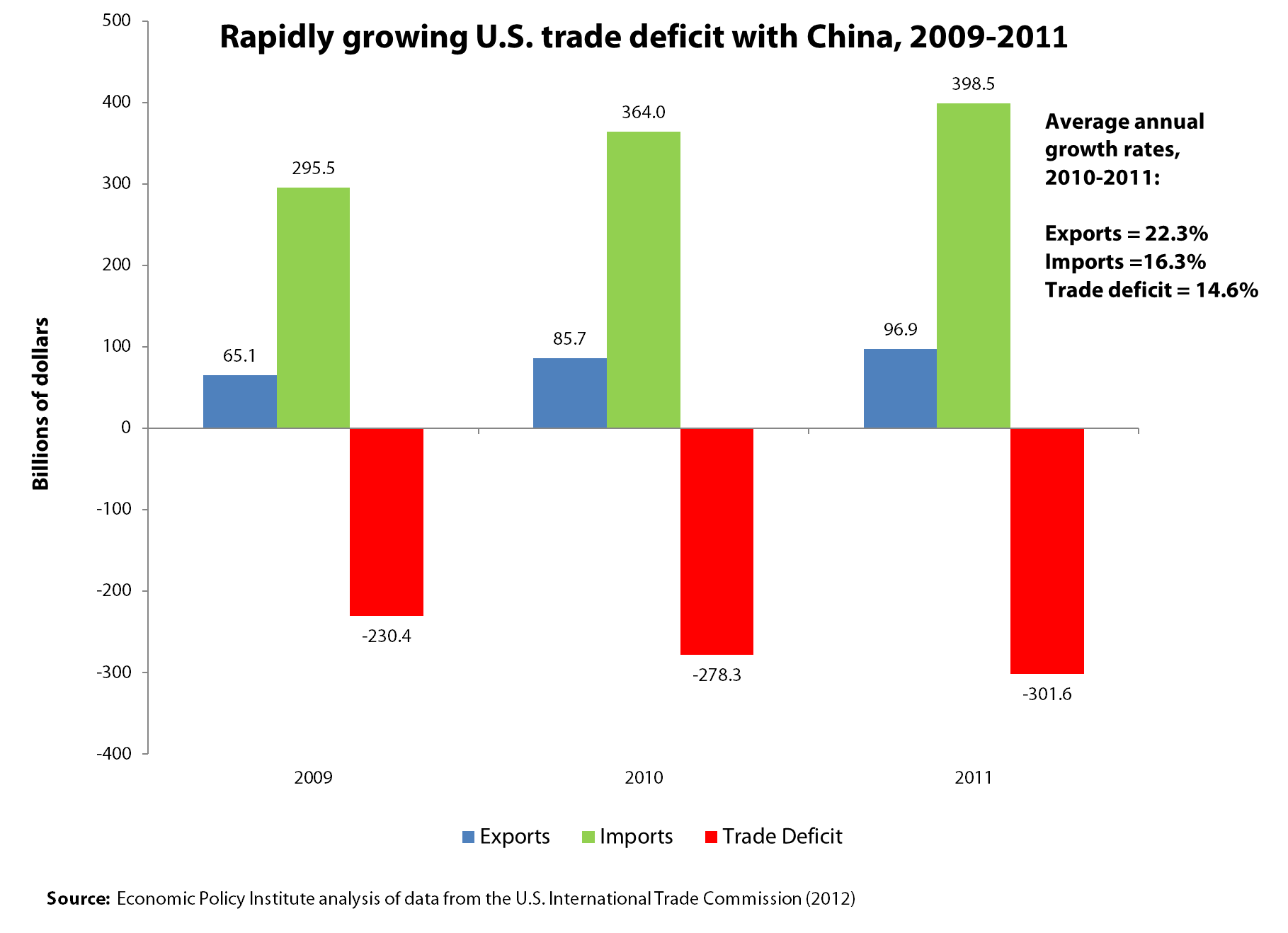

Exports to China increase at a relatively brisk pace of 22.3 percent on average over the past two years (since President Obama’s announced goal of doubling exports), as shown in the figure below. While this number sounds great in isolation, it was more than offset by the growth of imports from China, as shown in the figure; and U.S. trade deficits with China have soared.¹ So, even though exports to China are growing rapidly, the base (their initial level) is tiny compared with imports, which exceeded exports by more than 4-to-1 throughout this period. Therefore, in order to merely stabilize our trade deficit with China, exports would have to grow at least four times as fast as imports. In fact, imports from China grew nearly as fast as our exports to that country, and our bilateral deficit has increased 14.6 percent per year on average over the past two years.

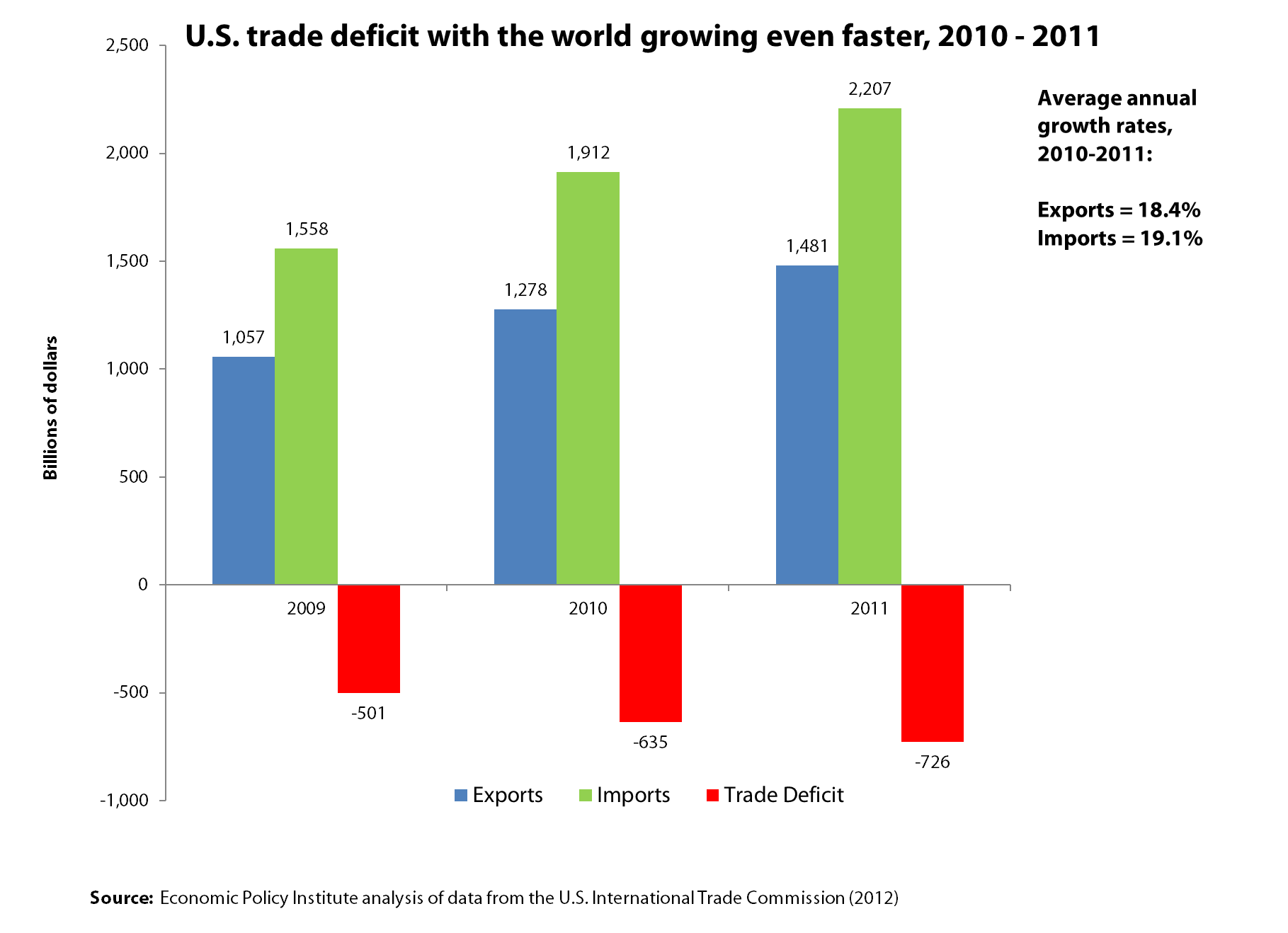

U.S. exports to the world have increased at a slightly slower rate of 18.4 percent per year over the past two years. Although this is slightly lower than the rate of growth of exports to China, at this rate, exports will double between 2009 and 2013, one year ahead of the goal set by President Obama. Time for a celebration and a tour of all those shiny new factories shipping exports to China, right? Not if we care about jobs. If imports and exports continue to grow at present rates, the U.S. global trade deficit will more than double by 2013 to more than $1 trillion. Millions more jobs will be lost, most of them in manufacturing. Again, the story is simple: Trade flows have two sides, imports and exports. Counting only one side tells you nothing about how policy has aided or hindered U.S. competitiveness in the global economy.

Readers will note that exports to China have grown only slightly faster than exports to the world over the past two years.Read more

Don’t cut the non-security discretionary budget!

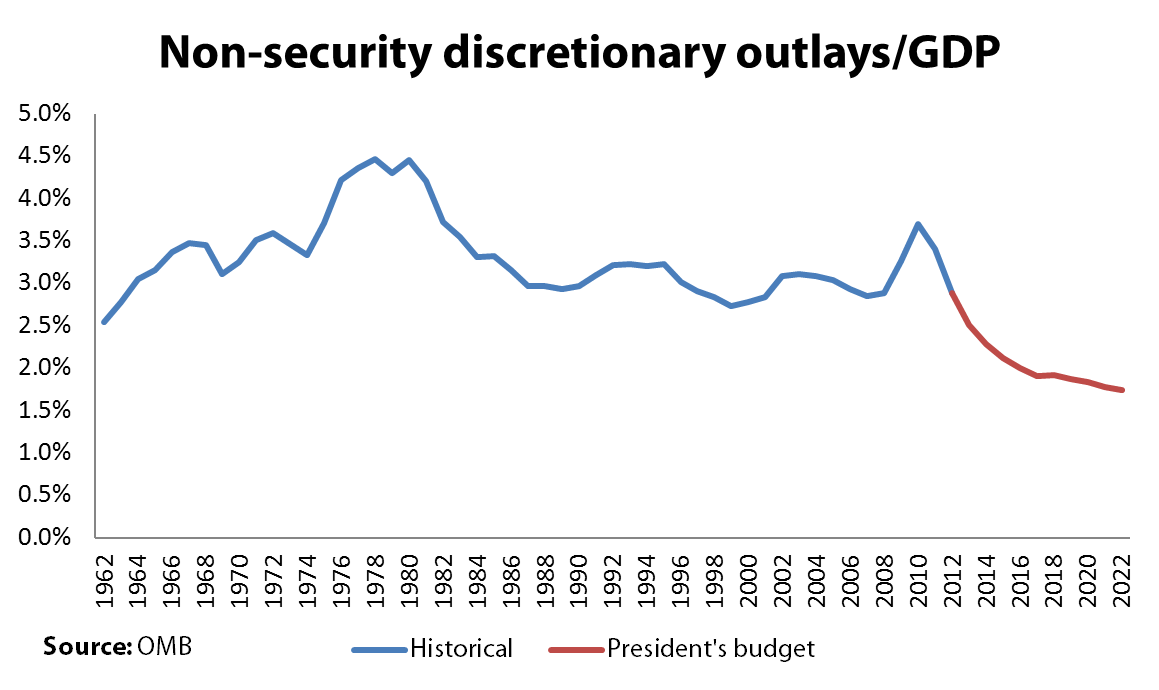

One of the most overlooked items of the federal budget is the non-security discretionary budget. Despite accounting for only about 15 percent of federal expenditure, it includes some pretty important government functions. Half of the non-security discretionary budget accounts for the entirety of the federal government’s role in economic development, consumer protection, public safety, environmental protection, as well as portions of the safety net. The other half is made up of vital public investments in infrastructure, education, and research and development, which are necessary to keep the economy strong and globally competitive for decades to come. In fact, the non-security discretionary budget is practically the sole provider of these investments, with few existing elsewhere in the budget.

We’ve given good marks to President Obama’s 2013 budget for its upfront job creation proposals, efforts to promote tax fairness, and for realistically stabilizing the debt-to-GDP ratio over the second half of the decade (as the output gap shrinks). But unfortunately, his budget proposal achieves much of its savings by maintaining the non-security discretionary cuts in the first phase of the Budget Control Act, the debt ceiling deal that established 10-year caps on discretionary spending. As a result, his budget forces non-security discretionary outlays down to their lowest level as a share of GDP ever recorded (the data begins at 1962). That’s even lower than the Bowles-Simpson proposal!

The president has admirably made public investments a high priority, promoting increases in transportation, school facility repair and modernization, job training, R&D, and college access. But this vision is hard to reconcile with a rapidly shrinking non-security discretionary budget, as it will lead to even steeper reductions to everything else, with disastrous consequences.

Working spouses cause inequality? Can this emerging zombie lie be killed?

A major new zombie lie is being launched: The claim that high inequality is due to more working spouses in high-income households and well-off people increasingly marrying other well-off people. This was part of James Q. Wilson’s recent op-ed in the Washington Post, which I addressed in an earlier blog post (though not on this point). My zombie lie detector went wild, however, after reading a very good New York Times article detailing new research showing “the [education] achievement gap between rich and poor children is widening, a development that threatens to dilute education’s leveling effects.” At the end of the article are two statements by conservative public intellectuals, one from Douglas Besharov and one from Charles Murray, attributing income inequality to working spouses.

To recall, here’s what Wilson wrote: “Affluent people, compared with poor ones, tend to have greater education and spouses who work full time.” Wilson then suggests that if these are the drivers of inequality, then it is best not to do anything about the problem, since, in his words, “We could reduce income inequality by trying to curtail the financial returns of education and the number of women in the workforce—but who would want to do that?”

Here’s what the Times‘ Sabrina Tavernise attributed to Murray in her piece:

The growing gap between the better educated and the less educated, he [Murray] argued, has formed a kind of cultural divide that has its roots in natural social forces, like the tendency of educated people to marry other educated people, as well as in the social policies of the 1960s, like welfare and other government programs, which he [Murray] contended provided incentives for staying single.”

And here’s what Besharov told Tavernise:

There are no easy answers, in part because the problem is so complex… . Blaming the problem on the richest of the rich ignores an equally important driver, he [Besharov] said: two-earner household wealth, which has lifted the upper middle class ever further from less educated Americans, who tend to be single parents. The problem is a puzzle, he [Besharov] said. “No one has the slightest idea what will work. The cupboard is bare.”

The basic claim, it seems, is that well-off families are more likely to have working spouses and that the spouses in well-off families are both more likely to have high earnings. Presumably this phenomenon has been growing, or else it cannot explain growing inequality. I address the issue of the role of the growth of two-earner households and inequality in this post but do not address the issue of assortative mating (rich marrying rich). Also, my focus is whether the “working spouses factor” contributes at all to our understanding of the key dynamic of income inequality, the growing income gap between the top 1 percent and the middle class.

To these folks demographic, rather than economic, trends are generating income inequality. Consequently, economic policy has had no role in causing inequality and can not ameliorate inequality either. Of course, this is only the latest effort to reduce inequality to a demographic phenomenon: The State of Working America has addressed other such claims going back to the first edition in 1988.

To explain inequality is to explain first and foremost the tremendous growth of income, wages and wealth that have accrued to the top 1 percent and the top 0.1 percent since 1979. How does the “working spouse” explanation hold up?

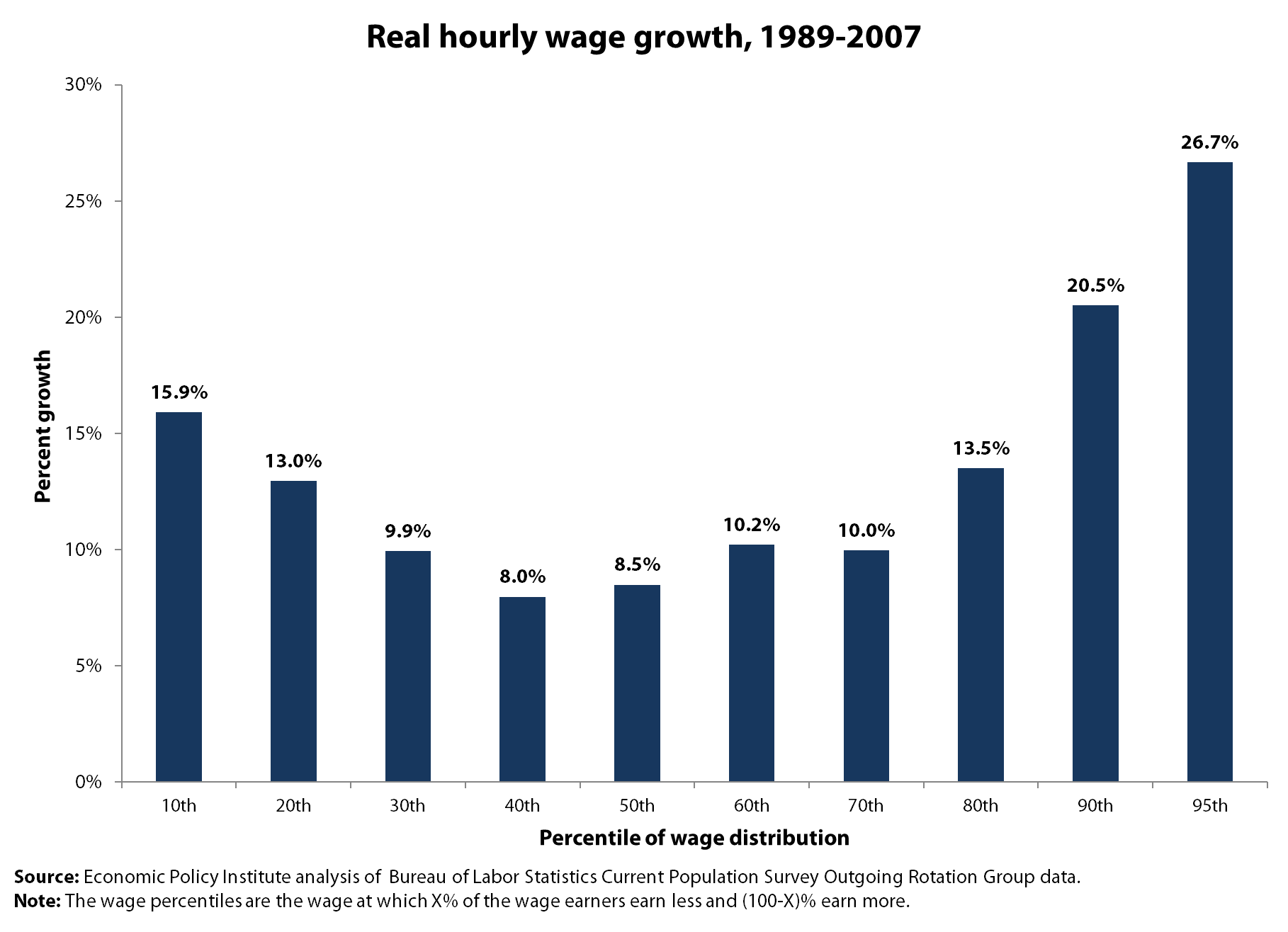

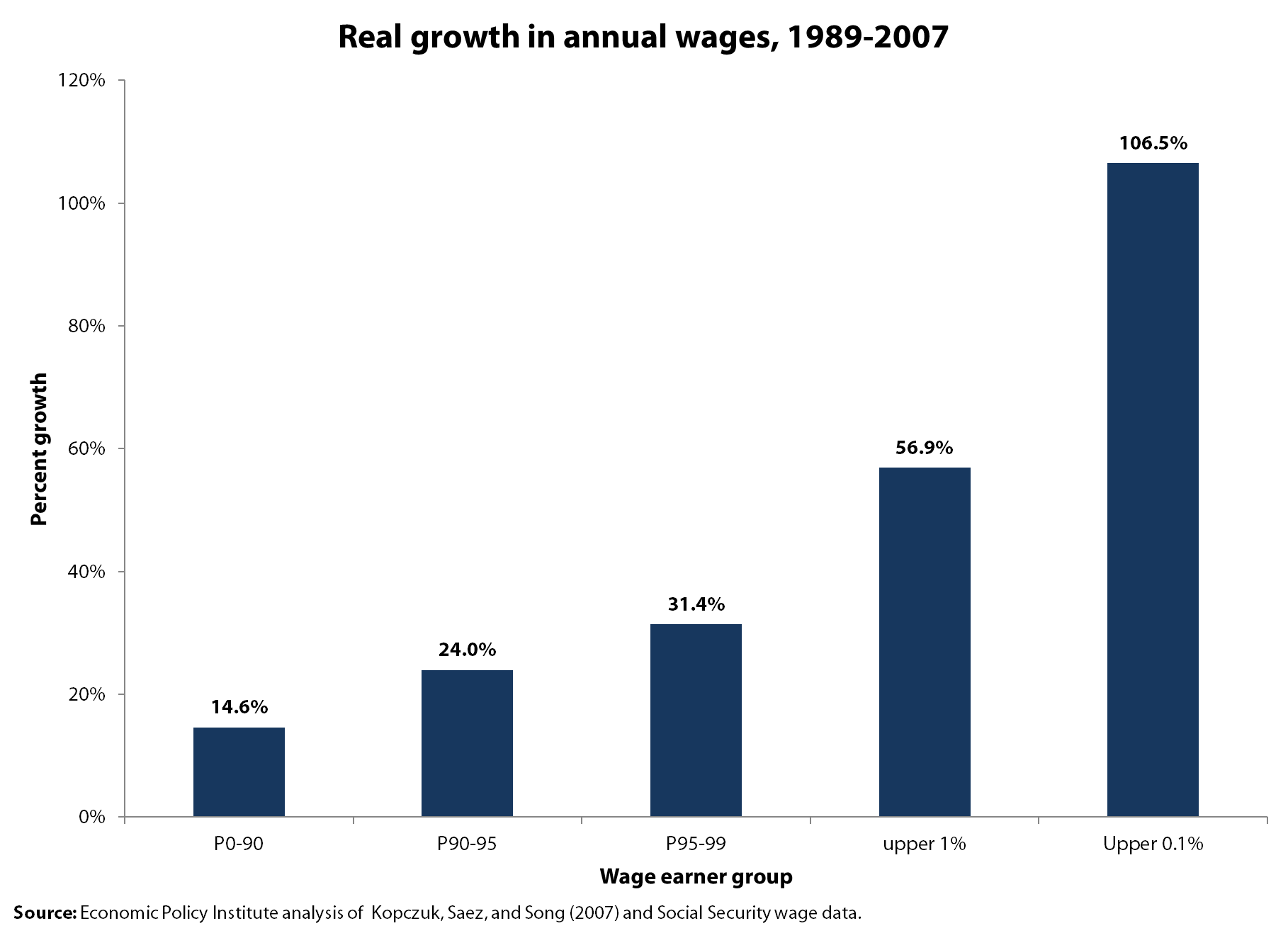

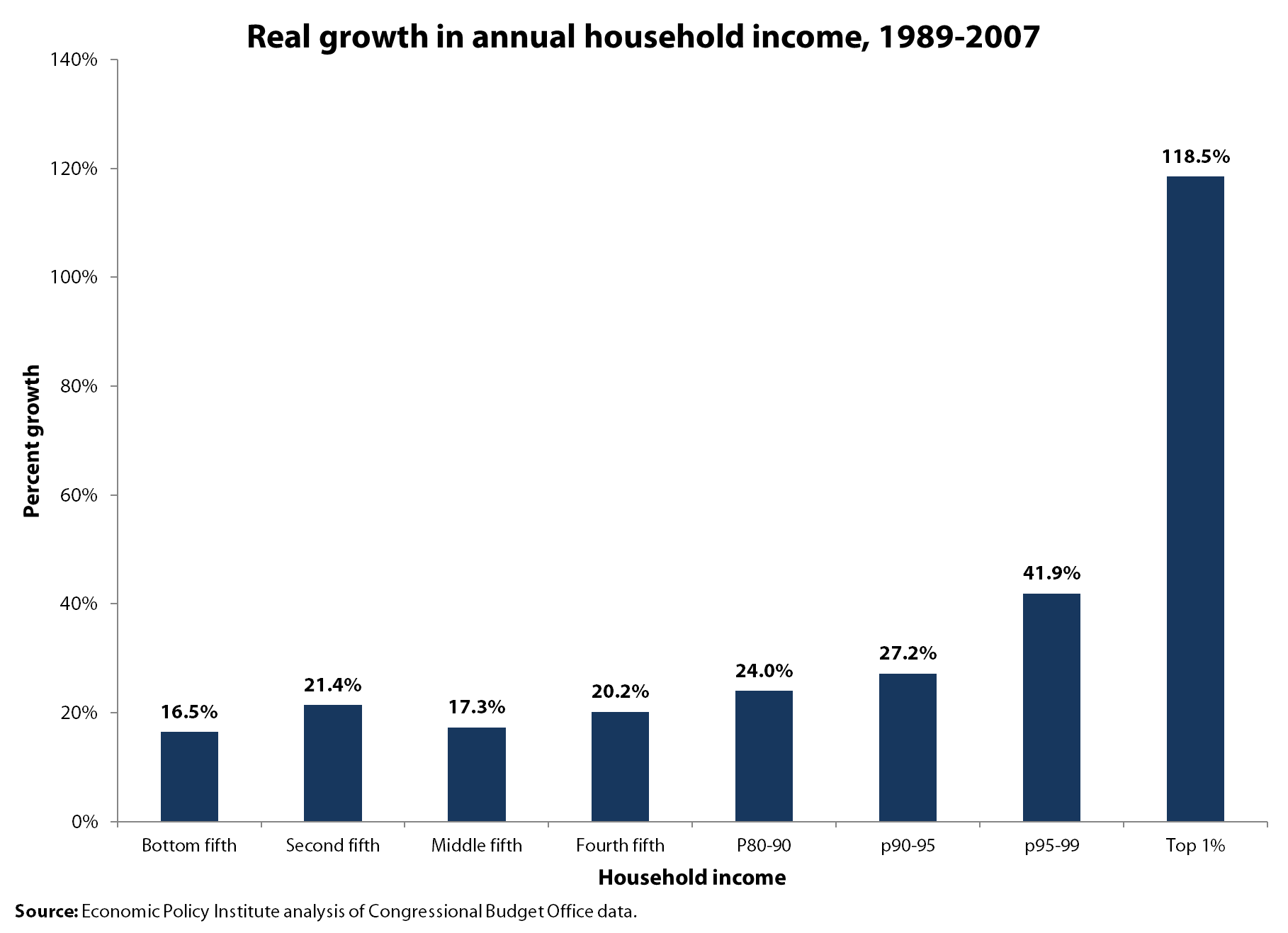

The first thing to note is that the presence of a working spouse, even a highly paid one, can potentially impact household income inequality but says nothing about the tremendous divergence of individual wages over the last few decades. Household incomes aggregate the labor income of all household members (which depends on how many members work, how much they work and how much they are paid), non-labor income (capital gains and so on) and any pensions, government transfers and other income. As we know, the top 1 percent of households managed to more than double its share of national income between 1979 and 2007. Josh Bivens and I have argued that the dynamics underlying growing household income inequality are rising wage inequality, rising inequality in receipt of capital income (capital gains, dividends and so on) and the shift toward more capital income and less wage income. The demographic factor of working spouses is about how people combine into households and does not address and certainly cannot explain the huge increase in the wage growth of the top 1 percent of wage earners versus every other group. Here is the chart on wage growth showing the top 1 percent gaining 131 percent between 1979 and 2010 while those in the bottom 90 percent saw their annual wages rise by 15 percent (mostly in the late 1990s).

Second, we can look directly at the two–earner phenomenon among the upper 1 percent and the top 0.1 percent from the work of Jon Bakija, Adam Cole and Bradley T. Heim who analyzed tax returns from 1979 to 2005.Read more

David Brooks’ bad example

Update (4:10 p.m. ET): Here’s some data (from EPI analysis of the Current Population Survey) on the share of those employed lacking a high school diploma or a GED certificate, labeled “less than high school,” by race/ethnicity and immigration status:

Share of employment with ‘less than high school’ education, 2011 |

|||

|

Race/ethnicity |

All | Native | Immigrant |

| All | 8.4% | 5.1% | 25.9% |

| White* | 4.2% | 4.1% | 6.0% |

| Black* | 7.2% | 6.7% | 10.6% |

| Hispanic | 28.6% | 11.6% | 44.3% |

| * Excluding Hispanics | |||

Note that just 4.1 percent of the native born white workforce is in this category. Only 5.1 percent of employment of all native-born Americans lacks a high school degree or a GED, with a slightly higher share among employed native-born blacks (6.7 percent).

Original post: I was struck by David Brooks’ example of bad behavior in his New York Times column today, writing, “I don’t care how many factory jobs have been lost, it still doesn’t make sense to drop out of high school.” Paul Krugman was struck by that same sentence. Brooks’ assumption, I guess, is that many workers have low wages because they never completed high school. He’s not alone in thinking that there are a lot of high school dropouts, but this is definitely not true. As the graph shows, the share of the workforce (ages 18-64) who have neither a high school or further degree (including a GED) has dropped tremendously in the last four decades, from 28.5 percent in 1973 to just 8.4 percent in 2011, a trend true among men as well as women. Oh, by the way, half of the “high school dropouts” in the workforce are immigrants, many of whom did not go to school in the United States and came here in their teens or later. You definitely can’t blame the erosion of workers’ wages on their failure to graduate from high school, since the vast majority did.

In fact, the education levels of our workforce have grown tremendously. As another example, the share of the workforce with a college degree or further education has doubled since 1973, growing from 14.6 percent in 1973 to one-third in 2011. And, by the way, the wages of those with a college degree (but no further education) have not increased in inflation-adjusted terms in 10 years, neither in the last recovery between 2002 and 2007 nor since. I wonder what bad behavior on their part caused this to happen.

A budget for adults (especially those who’d like a job)

President Obama’s FY2013 budget request, released today, is bound to get ample criticism from the right (and center-right) for not going far enough on near-term deficit reduction. As a few different articles have already highlighted today (for instance here and here), the president’s budget request does not honor a pledge he made to halve the deficit by the end of his first term. In reality, we’d all be in pretty big trouble if this budget chose to focus on promises as opposed to economic realities. Instead, the budget put forth by the administration today is a remarkably serious one – particularly given that Obama is running for reelection this year. The administration could have relied on gimmicks and austerity measures to focus solely on deficit reduction; instead we got a document that both emphasizes job creation and manages to hit fairly reasonable fiscal targets in the medium term.

The budget includes about $350 billion in temporary tax relief and investments to create jobs and jump-start growth. These investments are heavily front-loaded between FY2012-FY2014 – in fact, 96 percent of the proposed spending on these measures takes place in those years. Much of this investment in job creation is familiar, including policies such as:

- $94 billion for an extension of the payroll tax holiday for two years

- $44 billion for reforming and extending unemployment insurance for two years

- $30 billion to modernize schools over four years

- $30 billion for teacher stabilization and supporting first responders

- $50 billion to fund surface transportation priorities through 2022, with the investment front-loaded in the first three years

As we’ve stated before, this job creation package should be evaluated based on its scale, the difference it will make in the coming few years, its effectiveness and efficiency, and the way in which it is funded. The $350 billion figure is a decent amount to be spending on job creation, an amount that would raise employment levels significantly in 2012 and 2013. That is more than we can expect to see Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wisc.) propose in this year’s House Budget resolution. But with an 11 million jobs deficit, it still falls short of what’s needed.

Though not perfect, the investments highlighted in the budget are fairly well-targeted. Macroeconomic multipliers show that across-the-board, spending on public investments, income-support payments, state-and-local fiscal support, food stamps, infrastructure projects, unemployment insurance, and targeted refundable tax credits garner a much larger bang-per-buck than spending on various tax cuts and credits. And since our economic problems generally still stem from a lack of demand, it makes sense that boosting the ability of consumers to spend should be a top priority for the administration.

The president’s budget “funds” this investment by proposing a greater level of taxation on those who can most afford to pay – rhetoric we have been hearing from Obama for a while now. This includes around $1.5 trillion over 10 years from upper-income tax provisions, which include, among other things, letting the George W. Bush-era tax cuts expire and taxing qualified dividends as ordinary income for those making above $250,000 per year ($200,000 single filers).

Along with addressing the jobs crisis, this budget also puts the federal government on a sustainable fiscal path. The president’s budget achieves primary balance in 2018, meaning that, excluding interest payments, spending does not exceed revenues. Primary balance is a good measure for two reasons. First, interest payments are essentially payments on past—rather than current—policy decisions, so primary balance allows us to use a measure that doesn’t punish current presidents for debt that may have been incurred by past presidents. Second, primary balance also results in a stabilized debt as a share of GDP, and this budget stabilizes debt at 76.5 percent in 2022 after peaking at 78.4 percent of GDP in 2014 and gradually coming down. And while the budget does propose around $4 trillion in deficit reduction over 10 years, around $850 billion of these savings comes from capping Overseas Contingency Operations, and a good deal more comes from pursuing high-income tax cuts and other revenue proposals. Additionally, the president proposes achieving around $600 billion of that deficit reduction through health and other mandatory initiatives, almost half of which would come from Medicare providers.

As we said in a statement earlier today, this budget is not perfect and particularly disappoints when it comes to non-defense discretionary spending levels. Despite this reality, this budget does a pretty good job of investing in job growth while at the same time promoting greater fairness and responsibility.

President Obama’s FY 2013 budget: The Buffett Rule and progressive tax reform

The tax policies in President Obama’s budget request for fiscal year 2013 more closely resemble those proposed for the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction (i.e., the Super Committee) last September than those included in last year’s budget request. Consequently, this year’s budget raises more revenue (ostensibly to finance job creation) and does more to restore tax progressivity than previous budgets. Like the administration’s Super Committee proposals, the president’s 2013 budget proposes comprehensive tax reform, which would aim to raise $1.5 trillion over a decade, relative to current policies, from businesses and households making over $200,000 ($250,000 for joint filers).

In his recommendations to the Super Committee, President Obama proposed that tax reform should be guided by the Buffett Rule – that “no household making over $1 million annually should pay a lower share of its income in taxes than middle-class families pay.” The 2013 budget adopts a more clearly defined Buffett Rule from the president’s State of the Union address, which stated: “If you make more than $1 million a year, you should not pay less than 30 percent in taxes.” In a progressive tax code, effective tax rates are intended to rise with income, but tax code loopholes—overwhelmingly the preferential treatment of capital income over labor income—allow some millionaires and billionaires to pay lower tax rates than middle-class households. While short on details, the president’s 2013 budget suggests that the Buffett Rule would be implemented as a new minimum tax for millionaires, replacing the existing alternative minimum tax (which falls predominantly on upper-middle-class households). The budget also suggests that the Buffett Rule would give some deference to millionaires’ charitable contributions, but would nonetheless likely ensure that tax rates rise with ability to pay.

A recent Congressional Research Service report noted: “Tax reforms that are consistent with the Buffett rule would likely include raising tax rates on capital gains and dividends.” The president’s 2013 budget moves further in this direction than his previous budget requests. The 2013 budget again proposed ending the carried interest loophole and restoring the top rate on capital gains to 20 percent, but this budget also proposes taxing upper-income households’ qualified dividends as ordinary income (instead of a preferential 20 percent rate, as previously proposed). Again equalizing the tax treatment of income derived from work and that derived from investments should be at the core of progressive tax reform. This focus reflects income and inequality trends and raises revenue from those households best able to contribute to deficit reduction (the same households that disproportionately benefit from the last decade’s regressive, deficit-financed tax cuts).

To steer Congress toward tax reform, the president’s budget identifies revenue increases of $1.9 trillion, almost $1.6 trillion of which would come from sunsetting the upper-income George W. Bush-era tax cuts, capping the rate at which tax preferences reduce tax liability for upper-income households, and reinstating the estate tax at 2009 parameters, again all relative to current policy. The remaining tax proposals include closing business tax loopholes, ending fossil fuel preferences, and reforming the international tax code, which look quite familiar. (See For Joint Select Committee, many good options: Progressive revenue proposals would narrow budget gap by trillions for an analysis of the president’s tax proposals for the Super Committee.) Relative to current policies, the tax proposals in the 2013 budget would increase revenue as a share of GDP by 1.5 percentage points over the next decade – nowhere close to restoring revenue adequacy, but nonetheless an improvement over last year’s proposed 1.3 percentage point revenue increase.

Critically, the president’s tax proposals for 2013 appear to raise more revenue than those in his previous budget requests in order to finance a slew of job creation proposals closely resembling the American Jobs Act (which the president proposed financing with many of the progressive tax reforms in this budget, including caps on a wider range of tax preferences for upper-income households). The emphasis on near-term fiscal support gradually financed by tax increases on upper-income households—which will have a relatively small adverse impact on economic activity, unlike spending cuts—is good economic and fiscal policy. Federal tax and budget policy should accommodate bigger deficits today and reduce deficits as the output gap shrinks. The president’s tax policy proposals move in the right direction on this front, but they would also help to restore fairness to the tax code and begin to temper Gilded Age-levels of income inequality.

China responsible for bulk of the U.S. trade deficit in non-oil manufactured goods

The U.S. Census Bureau recently reported that the U.S. goods trade deficit increased from $645.9 billion to $737.1 billion in 2011 (an increase of $91.2 billion, or 14.1 percent). Crude and refined petroleum products were responsible for $61.3 billion, or 67.2 percent of the increase in the total goods trade deficit, as reported by the Census Bureau. The U.S. trade deficit in non-oil manufactured goods increased by $48.9 billion, or more than the residual.¹ The U.S. has a small, growing trade surplus in agricultural goods which increased from $36.2 billion in 2010 to $43.1 billion in 2011. We are, in effect, trading energy and capital intensive cash grains and other farm products for labor intensive manufactured goods.

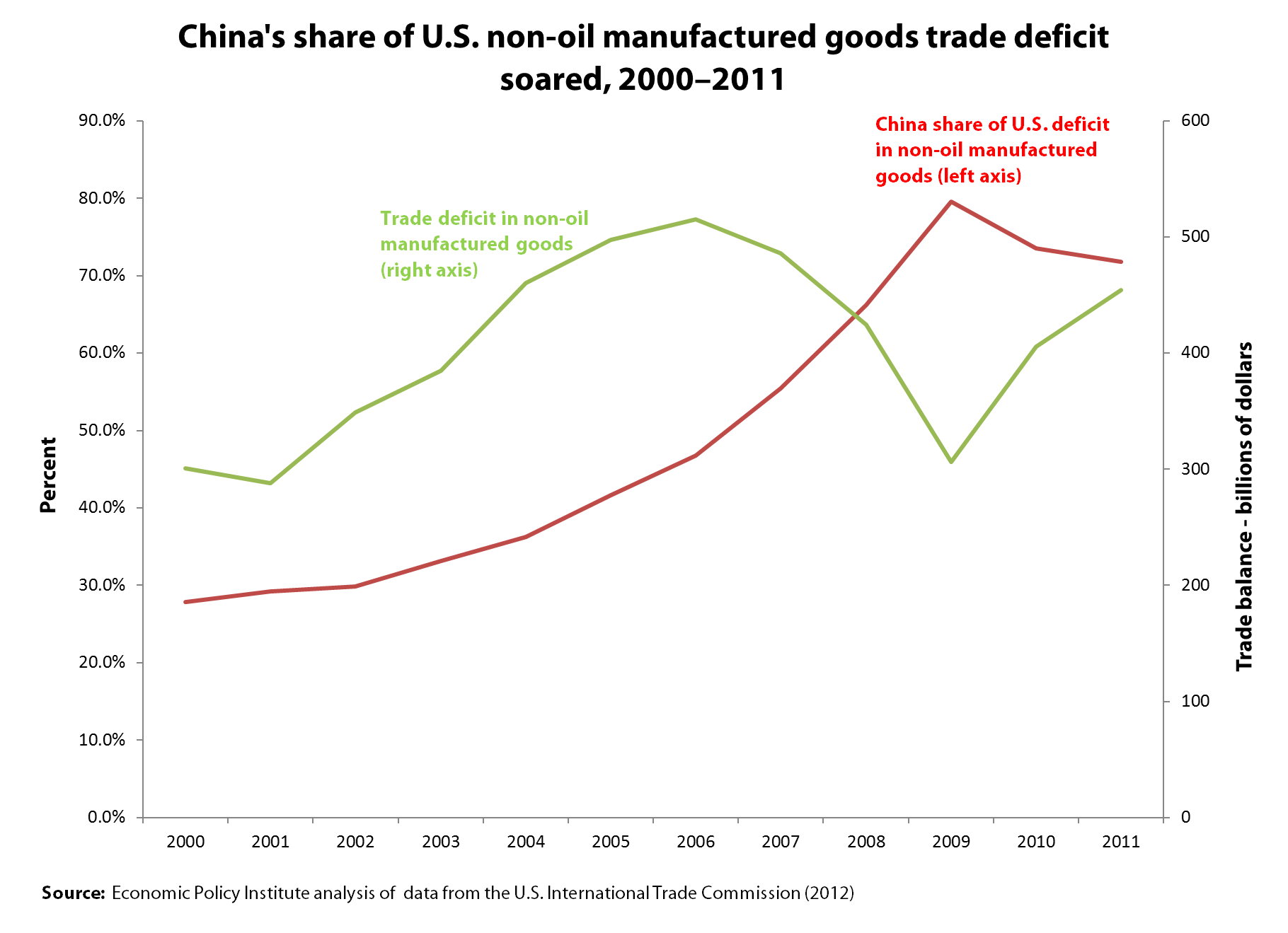

The U.S. has a large and rapidly growing trade deficit in non-oil manufactured goods, as shown in the figure below. This deficit reached a peak of $515 billion in 2006 (shown on the right axis), improved slightly in 2007 and then collapsed during the recession in 2008 and 2009 as employment, consumer incomes and demand for manufactured goods—especially durable products like automobiles—fell sharply. As a result, imports and the non-oil manufacturing trade deficit also declined in the same period.

The U.S. trade deficit in non-oil manufactured goods has been growing rapidly since 2009, as shown in the figure, which has contributed to the slow growth of manufacturing employment since the Great Recession. The U.S. lost 2.3 million manufacturing jobs between Dec. 2007 and the employment trough in Jan. 2010. Only 354,000 manufacturing jobs were added through Dec. 2011, an increase of 3.1 percent (BLS 2012). Manufacturing output, on the other hand, which reached its nadir earlier, in June 2009, has recovered much more strongly, up 16.0 percent since the trough. The difference is due, in part, to the rapid growth of the manufacturing trade deficit shown in the figure.

Throughout this period, imports of manufactured goods from China have continued to grow rapidly. Their share of the U.S. non-oil trade deficit in manufactured goods trade deficit rose steadily and more than tripled between 2000 and 2009 as shown on the red line in the figure (measured on the left axis). The U.S. trade deficit with China in these products increased in every year between 2000 and 2008. They fell only briefly in 2009, and hit new, record levels each year in 2010 and 2011, peaking at $326.1 billion in 2011. The U.S. trade deficit with China in non-oil manufactured products exceeded the overall bilateral deficit because the United States had a small trade surplus with China in raw agricultural products.²

Although China’s share of the manufacturing trade deficit has declined slightly in the past two years, as shown in the figure, China and five other Asian trading partners have been responsible for 80 percent or more of the U.S. trade deficit in non-oil manufactured products for the past three years. These trading partners are South Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Indonesia and Malaysia. These countries have been forced to manipulate their currencies and compete with China on unfair trade practices to avoid loss of market share and falling behind.

Each of these countries has engaged in substantial currency manipulation and four of the six (China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Malaysia) have been identified as maintaining heavily undervalued currencies, relative to the dollar. The share of these six countries in the U.S. manufacturing trade deficits ranged from 92.4 percent in 2009 to 81.0 percent in 2011.

What China has in common with most, if not all, of its Asian trading partners are a set of illegal trade practices including currency manipulation and subsidies and other markets barriers. As noted by the Alliance for American Manufacturing’s Scott Paul, China’s unfair trade policies “are now the single largest impediment to job growth in America.” It is time for the United States to get tough with China and other unfair traders and put an end to these policies. The first and most important step is to get tough with currency manipulators.

¹Detailed data on product and industry trade by country in this post were all based on EPI analysis of data from the U.S. International Trade Commission (2012).

²Note, however, that China has sustained a small trade surplus in processed food and beverage products with the United States for the past four years; this surplus was $386 million in 2011 (U.S. International Trade Commission 2012).

References

U.S. International Trade Commission (U.S.I.T.C.). 2012. USITC Interactive Tariff and Trade DataWeb. Washington, D.C.: U.S.I.T.C. Available at: http://dataweb.usitc.gov/scripts/user_set.asp (registration required). Accessed December 9, 2012.

No, NYT, there’s been no expansion of government benefits, no ‘entitlement society’

There was a very interesting story on the front page of the Sunday New York Times, “Even Critics of Safety Net Increasingly Depend on It,” detailing a range of views of people who have an anti-government political orientation yet depend heavily on government supports.

I want to strongly object to one part of the story that seems to support the notion that we’re becoming an “entitlement society.” The story claims that there’s been a major “expansion of government benefits,” which it says “has become an issue in the presidential campaign.” The Center for Economic and Policy Research’s Dean Baker sees some of the same problems.

Many of the facts presented in the story do not support that conclusion and the ones that do seem to support it are misleading. Here’s the key portion:

In 2000, federal and state governments spent about 37 cents on the safety net from every dollar they collected in revenue, according to a New York Times analysis. A decade later, after one Medicare expansion, two recessions and three rounds of tax cuts, spending on the safety net consumed nearly 66 cents of every dollar of revenue.

The recent recession increased dependence on government, and stronger economic growth would reduce demand for programs like unemployment benefits. But the long-term trend is clear. Over the next 25 years, as the population ages and medical costs climb, the budget office projects that benefits programs will grow faster than any other part of government, driving the federal debt to dangerous heights.

There are two things problematic with the comparison between 2000 and 2010. One is that the denominator is revenue when it should be expenditures since revenue has eroded because of tax cuts (acknowledged in the article) and because revenues fall in a recession (2000 had 4.0 percent unemployment, 2010 had 9.6 percent) since the fall in economic activity and income reduces revenue. Revenue as a share of GDP hit a 60-year low in 2010. Here’s what you find when you look at federal budget data: Entitlements (i.e., mandatory spending) as a share of federal expenditures were the same 53 percent of total outlays in 2007 as they were in 2000, so there was no trend towards expansion, at least before the recession hit. The mandatory share rose to 55 percent in fiscal year 2010 and 56 percent in 2011, a small increase.

The second problem is that the article suggests it is describing a situation of expanded benefits when, in actuality, the 2010 endpoint largely reflects that response of existing programs to the recession – more people do get unemployment insurance, Medicaid, food stamps and so on but once unemployment returns to low levels the expanded benefit rolls will retreat. (The American Reinvestment and Recovery Act and subsequent legislation also temporarily expanded the earned income tax credit, child tax credit, unemployment insurance, and food stamp benefits, among other programs – all cost effective fiscal stimulus and prudent economic policies but unlikely to be continued indefinitely.) It is easy to see that the bump up between 2007 and 2010 or 2011 was due to the greater income supports that are generated in a recession; if you take out the “income security” portion of mandatory outlays, which includes unemployment insurance and food stamps, then the mandatory share of outlays was roughly the same 45 percent of outlays in 2011 as its 46 percent share in 2000.

So, there’s no evidence to show we’re becoming an “entitlement society,” just that we’re low on revenues and the economy remains depressed. The citation of the safety net going from 37 percent to 66 percent (of revenues) has nothing to do with permanently expanding program eligibility or higher benefits, but much to do with cyclical factors and revenue erosion.

What about the future path of entitlement spending? Well, the article itself notes that the rise is due primarily to rising medical costs and an older population (i.e., more old people). This is an old story and given that the bulk of the increase is the fast-rising cost of medical services, the answer needs to be controlling the growth of health care costs. It is also the case that these rising health care costs will be a major burden to private-sector employers, so we are not facing a government problem but a national economic challenge. If we were to limit federal health expenditures, a la House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan (R-Wisc.), then the burden of this problem would fall on the elderly, their families, state and local governments, and private-sector employers. This doesn’t solve the problem, it just shifts the costs, likely exacerbating national health care expenditure in the process.

More lessons from testifying: Must explain that one person’s income is another’s cost

I’ve written one blog post already about my testimony this week on the EPA’s new standards for power plants and about how repeating near-universally held views about the economy flummoxed many of the subcommittee members to whom I was testifying.

Here’s another one that puzzled them: my claim that “one person’s income is another’s cost.” This one really buffaloed Rep. Mike Pompeo (R-Kan.), who seemed to think it was an idiosyncratic belief taught only where I went to graduate school.

The context is that I noted that the EPA’s new standards (sometimes referred to as the “toxics rule”) would create some jobs because firms would have to install and purchase pollution abatement and control equipment (scrubbers for smokestacks, for example). I noted that the need to undertake this pollution abatement investment was a cost from the perspective of the power plants, but would end up as income in the hands of workers doing the building and installation of the equipment and owners of firms in the pollution abatement sector.

Pompeo went on a strange tear about setting money on fire (yeah, I didn’t really get it either), but, just to prove that my “one person’s income is another’s cost” formulation is not some liberals-only shibboleth, check out the third slide in this PowerPoint presentation, based on the textbook of Greg Mankiw, an economic official in George W. Bush’s administration. Or this blog post on Freakonomics. Or this, from self-described libertarian Arnold Kling:

“It means that one person’s spending is another person’s income. When I buy a meal at a restaurant, the money I spend ends up as income for restaurant owners, cooks, wholesale food distributers, farmers, and so on.”

Is basic economics really this hard to get?

Anyway, in case Pompeo would like an honest-to-goodness businessman to make the same case, check out this from a story in Bloomberg Businessweek:

Meanwhile, Thermo Fisher Scientific in Waltham, Mass., is building emission monitors that power plants will need to measure toxins under the new rules. The regulations “could easily add $50 million to $100 million dollars in revenue in a year or two years,” says Chief Executive Officer Marc Casper, “which is significant for a company like ours.” The Institute of Clean Air Companies, a trade association representing businesses that make products to reduce industrial emissions, forecasts the industry will add 300,000 jobs a year through 2017 as a result of the EPA rules.

Lessons from testifying before the GOP House: Don’t assume people know basic economic principles

I testified before the House Subcommittee on Energy and Power yesterday regarding the economic impact of new EPA rules regulating toxic air pollution emitted by power plants. I made the simple point that when the economy is stuck in a “liquidity trap,” such regulatory changes can actually shrink the output gap and create jobs in the short-run by mobilizing idle savings into productive investments – a mobilization that today isn’t occurring through the traditional mechanism (falling interest rates) because we’re at the zero interest rate bound. The argument is far from revolutionary, but nobody else really seemed to be making it, so off to the Hill I went.

What really seemed to flummox some on the subcommittee, however, was when I stated the near-universally held view among macroeconomists that in the long run and if (and only if) the economy begins functioning well again, the unemployment rate a decade from now would best be estimated as “whatever the Federal Reserve wants it to be,” regardless of how many regulatory changes pass through Congress.

Why do I say this? Well, when the economy is working right, the Fed can cool down an overheating economy (man, to have that problem would be nice) by raising policy interest rates or can provide support to a flagging economy by lowering rates. While today’s extraordinarily weak economy has largely disarmed the Fed’s ability to provide a boost by lowering rates (the short-term policy rates the Fed manages have been stuck at zero since the end of 2008), if the economy begins functioning more-normally again then the unemployment rate will revert to pretty much what the Fed wants it to be because the tools at its disposal will be working again.*

This is neither necessarily good nor bad – the Fed may well “want” an unemployment rate much higher than is good for American workers (it’s happened before), but if that’s what they want, then they’ll get it. It’s a little hard to over-emphasize how widely held a view among economists this is. In an academic symposium (sorry, subscription required) on unemployment and monetary policy, not a single participant argued that the Fed doesn’t generally aim for an unemployment target nor did they argue that the Fed normally would not be able to hit it. Instead the argument was about the desirability of the Fed’s actual targets and/or how well the target was being estimated.

Given this consensus, it was a little odd to hear GOP representatives express slack-jawed disbelief about this statement. But it was extremely odd to hear a Ph.D. economist on the panel implicitly agree with them. And even odder was that the economist invoked a macroeconomic model run by a consulting firm, National Economic Research Associates (NERA) in their testimony arguing that that the “toxics rule” would cause economic harm.

But I’ve read the documentation of their study and their model assumes full-employment always and everywhere.** Which, (1) is why they’re wrong about the job-impacts of the rule in the short-run, when unemployment is clearly above any long-run “natural” rate and new investments will shrink the output gap and (very modestly) lower unemployment, and (2) makes it strange that they would deny that unemployment is not driven by regulatory changes. After all, their own model doesn’t admit that anything, regulatory change or anything else, can push the economy off of full-employment.

Myths of structural unemployment: The construction dimension

After feedback from readers, I think it would be useful to provide some context for the Economic Snapshot we released yesterday, What does construction have to do with it? The snapshot showed that very little of the rise in overall unemployment between 2007 and 2011 was due to unemployed construction workers (see the graph below). The data presented are the rise in unemployment compared to the rise in “unemployment other than construction.” In the early aftermath of the housing collapse in 2007, the overall unemployment rate was 4.6 percent, just 0.1 percent higher than if there were no construction sector. By 2011, the overall unemployment rate had risen to 8.9 percent and would have been 8.6 percent without construction. Thus, overall unemployment from 2007 to 2011 increased by 4.3 percentage points (going from 4.6 percent to 8.9 percent) and would have risen 4.1 percentage points without any construction sector (from 4.5 percent to 8.6 percent). Just 0.2 percentage points of the overall 4.3 percentage-point rise in unemployment can be explained by higher than average unemployment within the construction sector.

Unfortunately, some readers interpreted this analysis as denying either the real hardship faced by construction workers or the role of the bursting of the housing bubble on the economy. Neither was the case, so let me provide some context.

There has been persistently high unemployment for many years and a debate about what can and should be done about this. There are some prominent policymakers who believe that there is nothing that monetary or fiscal policy can do to address this high unemployment because the unemployment is mostly “structural,” meaning that there are sufficient job openings but the skills of the unemployed do not make them qualified for those jobs. That means it will take education and training of the unemployed and/or a long period of adjustment until we work our way through a structural change. In this view, neither monetary nor fiscal policy can successfully lower unemployment. One of the main narratives associated with this point of view focuses on construction, an intuitively plausible story (though not actually true): We built up substantial employment in construction during the housing boom, employment that went to relatively “unskilled” workers, and now that the bubble has burst and substantial job losses have resulted, we are left with a large pool of unemployed construction workers who have not yet found themselves new jobs in other sectors.

Consider the interview in the Wall Street Journal last year with Charles Plosser, the president of Philadelphia’s Federal Reserve Bank. After asking Plosser whether monetary policy can change the high unemployment picture, the interviewer, Mary Anastasia O’Grady, paraphrased his unequivocal response: This mess was caused by over-investment in housing, and bringing down unemployment will be a gradual process. Plosser said:

“You can’t change the carpenter into a nurse easily, and you can’t change the mortgage broker into a computer expert in a manufacturing plant very easily. Eventually that stuff will sort itself out. People will be retrained and they’ll find jobs in other industries. But monetary policy can’t retrain people. Monetary policy can’t fix those problems.”

In 2010, Narayana Kocherlakota, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, said that “a lot” of our unemployment was structural and not subject to influence by Federal Reserve Board monetary policy, specifically:

“Firms have jobs, but can’t find appropriate workers. The workers want to work, but can’t find appropriate jobs. There are many possible sources of mismatch—geography, skills, demography—and they are probably all at work. Whatever the source, though, it is hard to see how the Fed can do much to cure this problem. Monetary stimulus has provided conditions so that manufacturing plants want to hire new workers. But the Fed does not have a means to transform construction workers into manufacturing workers.”

So, the snapshot addresses the structural unemployment issue these observers raise and shows that the unemployment problem goes way beyond the pool of unemployed construction workers. This in no way diminishes the importance of the bursting of the housing bubble in generating the recession nor the severe employment losses in construction. As I wrote in an earlier paper, “It is true that construction has lost many jobs in this downturn, losing nearly 2 million jobs from the start of the recession through the second quarter of 2010. This accounts for about 25% of all private-sector jobs lost. Is this what’s fueling the unemployment problem? The answer is “No, not at all.””

There were severe job losses in construction and construction has very high unemployment, as it did in 2007. Construction unemployment, however, did not fuel the rise of unemployment to 10 percent and it does not explain why it currently exceeds 8 percent. We do know that those who lost their construction jobs exited unemployment by either taking jobs in other sectors, leaving the labor force (i.e., giving up) or leaving the country, though we do not know how many chose the particular exit paths. We also know that there would be very high unemployment even if we could set aside the very high and troubling unemployment of construction workers. Solving our unemployment problem is not really about turning construction workers into manufacturing workers (as Kocherlakota suggests) or into nurses (as Plosser suggests). Rather, we need to have more job openings and more jobs in nearly every sector. And a wide array of policies can make that happen, including monetary policy, housing policy, fiscal policy and exchange rate policy. One such federal policy would be to undertake infrastructure projects in transportation and in modernizing schools that would employ construction workers and also generate jobs in related industries as well as throughout the economy as newly employed construction and other workers spend their wages.

Auto industry roars back, everyone cheers (except anti-government conservatives)

I’d like to add some thoughts to Charles Blow’s entertaining and informative blog post about Karl Rove and Chrysler’s “It’s halftime in America” Super Bowl ad. The little dust storm over the commercial is fun to watch, and the public’s reaction—which has been overwhelmingly positive—tells me that Americans might be ready, at long last, to appreciate the single most effective economic intervention of the Obama administration, the rescue of the domestic auto industry.

For those who missed it, the commercial (watch below) has Clint Eastwood narrating scenes of the rebirth of Detroit, both the city and its industry, which were weak from decades of decline and, as Eastwood says, knocked down, but not out, by the Great Recession.

Today, the city’s in worse shape than the industry, but the automakers’ new plants, new models, sales revival and new jobs have created a sense of hope for a lot of people who have seen rock bottom. Against all the odds, Chrysler Corporation, which was not just knocked down, but was declared clinically dead by most experts five years ago, had the strongest year-over-year U.S. sales increase in January and continues to gain market share. Ford and General Motors both posted huge profits last year, and GM regained its place as the world’s auto sales leader.

This nearly miraculous, feel-good story has made conservatives dyspeptic. Mitt Romney and most Republicans in Congress opposed the federal government’s loans and restructuring of GM and Chrysler. They were happy to saddle President Obama with the catastrophic job losses that would have resulted. The Center for Automotive Research forecast the loss of 2.5 million jobs and EPI’s Rob Scott estimated the losses would range between 2.5 and 3 million jobs, while Moody’s Analytics’ Mark Zandi estimated the damage at about 1.5 million jobs.

Conservative opponents like Sen. Richard Shelby (R-Ala.), and even Zandi, who supported the rescue plan, predicted that the rescue would end up costing taxpayers upwards of a hundred billion dollars. They assumed the initial loans would not be repaid and would lead to additional loans when the companies failed to meet their sales and revenue targets.¹ They were wrong. Totally, absolutely wrong. Zandi has, at least, been forthright that things turned out far better than he feared.

Nevertheless, because TARP funds were used to save the auto companies, and because TARP is still widely reviled, most Americans opposed the rescue as just another corporate “bailout.” It didn’t help that the Big 3 were unpopular and their executives were tone deaf and overpaid. Add to this mix a right-wing effort to discredit the United Auto Workers and blame it for the industry’s woes, and it’s easy to see why President Obama has had trouble making people understand what a dramatic success his (and George W. Bush’s) policy has been. What should have been a huge re-election asset has been viewed as a liability, even in Michigan and Ohio!

But maybe the public does get it now. If they do, Rove and Fox News will have every reason to choke on a commercial that never mentions the government or Obama but celebrates the fact that a key U.S. industry just might win the second half.

¹As EPI’s Robert Scott points out, the rescue made both fiscal and policy sense, even if the loans were never repaid.

A cheaper dollar is not enough

My colleague Josh Bivens is right to call Christina Romer on her failure to note the importance of currency manipulation on the plight of U.S. manufacturing. But, he leaves us with the impression that the story ends there, and that a targeted manufacturing policy is simply a poor second-best reaction to the governing class’ refusal to deal with our overvalued dollar. It’s not. Even if Romer had acknowledged the currency problem, she still wouldn’t have been, as it were, on the money.

Romer dismisses the notion of “special treatment” of manufacturing (a euphemism for industrial policy – the policy that still dare not say its name), as a sentimental effort to turn back the tide of history, which conventional economics wisdom tells us has thrown American goods production into its trash heap. In the same news cycle, Larry Katz of Harvard tells the New York Times that an increase in manufacturing jobs is “implausible.”

But what is really implausible is the notion that America’s creditors will continue to finance our current account deficit forever. The mills of macroeconomic adjustment may grind slowly, but sooner or later—with or without a change in U.S. dollar policy—they will grind away the dollar’s inflated position in the world. Assuming an eventual global recovery, foreign investors will eventually find more profitable ways to invest their money (in their own economies, for example) than to keep lending it to American consumers at low rates and with the increasing risk that they will be paid back in devalued dollars.

At that point, the market will force the dollar down, making us more price competitive. But this will not be costless. Given that a large chunk of what we buy—including most of our oil—comes from abroad, the initial impact will be to raise the cost of living here, undercutting real incomes.

Moreover, time has not stood still. After 30 years of surrendering markets and off-shoring production, Americans no longer dominate the upper reaches of the global supply chains. The world is now full of competitors whose governments will use every possible policy tool to keep, and expand, their share of high value-added markets. So, in the absence of something similar here, our workers will be competing on the basis of cheaper labor costs.

It’s already happening. Two tier wages systems, in which younger workers get paid much less are now standard practice in many American factories. As Rich Trumka said to me a few months ago, “What makes you think that two-tiers could not turn to three?” The Obama administration plays up the General Electric decision to bring the production of a water heater back from China to a plant in Kentucky. What it plays down is that the hourly wage went from $20 to $13 per hour.

Some have criticized President Obama’s proposals as cynical election-year half-measures. They may be right. Still, it is, finally, a step in the right direction. Even with a cheaper dollar, laissez-faire domestic policy is not going to bring back the American Dream.

‘Nonsense fact’ about union workers used in Super Bowl ad

That’s how the Washington Post fact checker, Glenn Kessler, put it in his review of the following assertion used in the Super Bowl ad (watch below) by the Center for Union Facts*: “Only ten percent of people in unions today actually voted to join the union.”

Kessler dug in to see where that came from and apparently it is an “estimate [of the] the proportion of employees who both would have voted for the establishment of a union at their companies and were still in their jobs.” As Kessler points out, this has no bearing on the extent to which workers currently covered by collective bargaining would vote to maintain collective bargaining. It is as relevant, as Jared Bernstein points out, as “saying Virginia isn’t a state because none of its current residents voted for statehood.”

What are the facts? Richard Freeman (Harvard University) and Joel Rogers (University of Wisconsin) report on page 69 in their book, What Workers Want, that 90 percent of union workers wanted to keep their union based on their answer to the question, “If a new election were held today to decide whether to keep the union at your company, would you vote to keep the union or get rid of it?”

Union workers have many special legal rights and protections. For instance, union workers by law have the right to vote for union officers and any dues increase, initiation fee or assessment. The laws protecting internal union democracy are far stricter than those for corporate governance and shareholder rights. Plus, workers also have clear rights to decertify unions. This ad and this “fact” do not capture what union worker rights are nor even attempt to reflect what union workers’ views are of collective bargaining.

In fact, a much larger share of the non-managerial workforce wants a union than has a union. Freeman wrote in 2007:

“Given that nearly all union workers (90%) desire union representation, the mid-1990s analysis suggested that if all the workers who wanted union representation could achieve it, then 44% of the workforce would have union representation.”

So, if workers could freely have a union when they wanted one, union representation in the United States would be on par with that of Germany.

*By the way, the CUF is just a small part of an array of misleading public relations efforts conducted by Richard Berman on behalf of special interests.

The tax expenditure of the 1%

The Tax Policy Center’s new report on the distribution of tax expenditures strengthens the case for increasing tax progressivity and raising needed revenue by ending the preferential treatment of capital income (subject to a 15 percent tax rate versus a top marginal income tax rate of 35 percent). TPC’s analysis looks at seven broad categories of individual income tax expenditures: exclusions, above-the-line deductions, the preferential treatment of capital gains and dividends, itemized deductions, nonrefundable tax credits, refundable tax credits, and other miscellaneous tax expenditures. Guess which category of tax expenditure provides by far the most lopsided benefit to upper-income households?

That would be the way the tax code preferences capital income over wage and salary income, compounded by the heavy concentration of capital income at the top of the earnings distribution. In 2011, the top 1 percent of households by cash income received a whopping 75.1 percent of the benefit from the preferential treatment of capital gains and dividends. The broad middle class—defined here as the middle 60 percent of households by cash income—received only 3.9 percent of that benefit. Upper-income households also do well by tax exclusions and itemized deductions, but the share of these tax expenditures accruing to the top 1 percent of households—at 15.9 percent and 26.4 percent, respectively—don’t come close to the windfall afforded by a 15 percent rate on capital income.

This should come as no surprise if you’ve read about the Buffett Rule and former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney’s 13.9 percent effective tax rate: Capital income is terribly concentrated at the top of the earnings distribution and the preferential tax treatment of capital income even allows some millionaires and billionaires to pay lower effective tax rates than many middle-class households. Indeed, a recent Congressional Research Service report suggested that the tax reforms most consistent with implementing the Buffett Rule would be raising tax rates on capital gains and dividends. Additionally, TPC’s distributional analysis of taxes on long-term capital gains and qualified dividends shows that the top 1 percent of households by cash income (with income above $533,000) will pay 70.5 percent of capital gains and dividends taxes in 2011, contrasted with just 2.3 percent for the broad middle class (with incomes between $17,000 and $103,000).