Sure, it’s weak, but this ‘so-called recovery’ is no weaker than the last one, Greg Mankiw

On Monday, EPI labor economist Heidi Shierholz pointed out that job growth during the current recovery has been stronger than job growth during the recovery following the 2001 recession. In addition, the jobs recovery from the Great Recession isn’t too far off the pace following the 1990 recession; private sector job growth 33 months into the 1990 recovery was 3.4 percent, while it’s 2.7 percent for the current recovery. Shierholz’s main point is that it’s the historic length and severity of the Great Recession, and not unprecedentedly poor job growth in the recovery, that explains why we’re still so far from full employment 33 months since the recession officially ended.

Greg Mankiw, however, isn’t about to highlight that fact. Mankiw, who was chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under George W. Bush from 2003-05 and currently serves as an economic adviser to presidential candidate Mitt Romney, posted the graph below on his blog last weekend with the dismissive headline, Monitoring the So-called Recovery:

The graph shows the employment-to-population ratio (or EPOP) going back to 2004. We see the EPOP drop steeply during the Great Recession, followed by a mostly flat trajectory since. But let’s add a line to Mankiw’s graph for a direct comparison of this recovery to the last one:

It’s clear from the figure that EPOP fell much further and faster during the Great Recession than the 2001 recession. But looking to the right of the vertical line, we see that EPOP growth (or lack thereof) in the current recovery follows the same trend (i.e., flat) as the recovery after the 2001 recession. In other words, the key difference between EPOP at this point in the current recovery versus the same point in the last recovery (during which Mankiw chaired the CEA) is the length and severity of the recession that preceded them.

Yes, this recovery is slow, and certainly there is no excuse for the current complacency from policymakers about the jobs crisis, but the folks over at Angry Bear have a good adage for Mankiw: “People who live in glass houses should be careful about throwing rocks.”

With research assistance from Heidi Shierholz and Hilary Wething

The utter wrongness of people who complain about double-counting Medicare savings

In a post today, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget reiterated its position that it is double-counting to argue that the Affordable Care Act both reduces the deficit and extends the life of the Medicare trust fund. Chuck Blahous, the Medicare actuary who started this mess, and Peter Suderman over at Reason agree.

Their position is wrong, wrong, wrong. First, let’s clarify the baseline. CRFB points out, correctly, that there are two baselines to choose from. The Trust Fund Baseline, which is used by Blahous, assumes that a program’s spending is constrained by the resources in its trust fund. If the trust fund is gone, the spending will automatically be cut. The Unified Budget Baseline, on the other hand, assumes that spending on programs will continue as scheduled, and the federal government will simply borrow money to ensure that benefits are not cut.

As many pointed out, the Blahous baseline is ridiculous. If spending is constrained by the trust fund, then we don’t have a problem. But the main purpose of the Affordable Care Act—heck, why we’re talking about deficit reduction in the first place!—is the assumption that we do have a problem. And even if—as CRFB states—both baselines are equally valid, it’s clear from the administration’s rhetoric that it is using the latter.

So, how can it be that a dollar can both be used to reduce the deficit and extend the trust fund? Well remember that under the baseline we’re using, program outlays aren’t constricted by the trust fund. Outlays have nothing to do with the trust fund. So therefore, extending the trust fund doesn’t cost anything, because it’s an accounting identity with no programmatic relevance.

Now, you might say that the Obama administration is being misleading, talking about extending the life of a trust fund, when under its own assumptions, the trust fund doesn’t matter. But while it may not have any impact on spending levels, it does matter for other reasons. While the size of the trust fund doesn’t determine how much spending can be done, it does potentially impact how the spending is financed. In the case of Social Security, for example, the trust fund commits income taxes (a more progressive revenue stream) in the future to redeem past surpluses financed by payroll taxes (a less progressive revenue stream); so declaring the trust fund meaningless in this case would profoundly affect the distribution of Social Security’s costs.

Trust funds also have political relevance. Even if you assume that Medicare outlays will be unaffected by the trust fund, having an insolvent trust fund opens a program up to political attacks. We’re seeing that right now with Social Security. So even if the trust fund doesn’t matter to the program’s operation, it still matters to shore of the program’s political strength. That’s something that seniors—and really anyone fond of Medicare—should care about.

A rising tide for increasing minimum wage rates

On Monday, the New York Times reported on the growing groundswell to raise wages for the lowest-paid workers by increasing minimum wage rates. Legislators in New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Illinois are all looking toward raising their state minimums. At the same time, Iowa Sen. Tom Harkin has introduced a bill that—among making other critical investments, strengthening worker protections, increasing tax fairness, and reducing the federal deficit—would raise the federal minimum wage to $9.80 per hour over three years and then index it to inflation.

As Table 1 shows, increasing the federal minimum wage in three steps to $9.80 per hour, as described in the Harkin bill, would raise the wages of 28 million Americans. About 19.5 million workers whose wages are between the current minimum and the proposed $9.80 rate would be directly affected. Another 8.9 million whose wages are just above the proposed minimum would also see a pay increase through “spillover” effects as employers adjust their overall pay scales.

*Total estimated workers is estimated from the CPS respondents for whom either a valid hourly wage is reported or one can be imputed from weekly earnings and average weekly hours. Consequently, this estimate tends to understate the size of the full workforce. **Directly Affected workers will see their wages rise as the new minimum wage rate will exceed their current hourly pay. ***Indirectly affected workers currently have a wage rate just above the new minimum wage (between the new minimum wage and the new minimum wage plus the dollar amount of the increase). They will receive a raise as employer pay scales are adjusted upward to reflect the new minimum wage. Source: EPI Analysis of 2011 Current Population Survey, Outgoing Rotation GroupWorkers affected by proposed federal minimum wage increase

Federal minimum increased to $9.80 per hour in three increases of 85 cents, modeled for July 2012, 2013, and 2014

Total estimated workers in third year*

127,361,000

Directly affected**

19,485,000

Indirectly affected***

8,869,000

Total (directly & indirectly) affected

28,354,000

Table 2 highlights some demographic characteristics of the affected workers. Fifty-four percent are women and 54 percent work full-time. The overwhelming majority (87.9 percent) are at least 20 years old. This may come as a surprise to some, as minimum-wage workers are often portrayed as teenagers working part-time. The reality is that only 12 percent of those who would be affected by the raise are teenagers and only 15 percent work fewer than 20 hours per week.

*Directly Affected workers will see their wages rise as the new minimum wage rate will exceed their current hourly pay. **Indirectly affected workers currently have a wage rate just above the new minimum wage (between the new minimum wage and the new minimum wage plus the dollar amount of the increase). They will receive a raise as employer pay scales are adjusted upward to reflect the new minimum wage. Source: EPI Analysis of 2011 Current Population Survey, Outgoing Rotation GroupDemographic characteristics of affected workers

Directly affected*

Indirectly affected**

Total affected

% of total affected

Total

19,485,262

8,868,654

28,353,916

100.0%

Female

10,924,035

4,527,632

15,451,666

54.5%

Male

8,561,228

4,341,022

12,902,250

45.5%

Part-time (<20hrs/week)

3,327,498

918,690

4,246,187

15.0%

Mid-time (20-34hrs/week)

6,599,616

2,167,363

8,766,979

30.9%

Full-time (35+ hrs/week)

9,558,149

5,782,601

15,340,750

54.1%

Age 20 +

16,509,188

8,421,003

24,930,191

87.9%

Under 20

2,976,074

447,651

3,423,725

12.1%

White

10,959,722

4,960,138

15,919,860

56.1%

African American

2,741,079

1,285,583

4,026,662

14.2%

Hispanic

4,654,719

2,035,908

6,690,626

23.6%

Asian

1,129,742

587,025

1,716,767

6.1%

Furthermore, low-wage workers tend to spend rather than save an additional dollar earned, often because they have little other choice. The additional household consumption generated by this boost to low-wage workers’ paychecks would benefit the labor market as a whole, because the resulting economic activity translates into job growth. After controlling for a reduction in corporate profits resulting from the minimum wage increase, and assuming some of the business expense of paying higher wages is passed on to consumers, the net effect of the proposed minimum wage increase is an increase in economic activity of over $25 billion over the next three years, which would generate roughly 100,000 new jobs.

Economic effects of proposed federal minimum wage increase

| Federal minimum increased to $9.80 per hour in three increases of 85 cents, modeled for July 2012, 2013, and 2014 | |

|---|---|

| Increased wages for directly & indirectly affected* | $39,677,170,000 |

| GDP Impact** | $25,115,648,697 |

| Jobs Impact*** | 103,000 |

*Increased wages: Total amount of increased wages for directly and indirectly affected workers.

**GDP and job stimulus figures utilize a national model to estimate the GDP impact of workers' increased earnings, after controlling for reductions to corporate profits.

***The jobs impact total represents full-time equivalent employment.The increased economic activity from additional wages adds not just jobs but also hours for people who already have jobs. Full-time employment takes that into account, by essentially taking the number of total hours added (including both hours from new jobs and more hours for people who already have jobs) and dividing by 40, to get full-time-equivalent jobs added. Jobs numbers assume full-time employment requires $115,000 in additional GDP.

Source: EPI Analysis of 2011 Current Population Survey, Outgoing Rotation Group. Job impact estimation methods can be found in: Hall, Doug and Gable, Mary. 2012. The benefits of raising Illinois' minimum wage. Washington, D.C.: Economic Policy Insitutute; and Bivens, Josh L. 2011. Method memo on estimating the jobs impact of various policy changes. Washington, D.C.: Economic Policy Institute.

In a historical context, the increase proposed by the Harkin bill is long overdue. As John Schmitt and Janelle Jones at the Center for Economic and Policy Research explain, the real value of the minimum wage is far below its historical levels, despite the fact that the low-wage workforce is older and better educated than ever before. Congress has had to raise the minimum wage 17 times since its peak value in 1968 in order to combat inflation. Indexing the minimum wage, as 10 states have already done, would fix this problem once and for all.

The lingering effects of the recession make this an even more critical time to raise the wage floor. Even as employment has slowly picked up in the recovery, wage growth is still painfully weak. Moreover, recent reports show that low-wage work has been driving much of the recent job growth. (This also means that the figures here may actually understate the number of people who would be affected by an increase in the federal minimum.) The Harkin bill, and similar state proposals, would give much-needed help to these workers and provide additional stimulus to the U.S. economy – all without costing anything to taxpayers.

Since when does each and every budget policy proposal have to singlehandedly eliminate the deficit?

In all seriousness, when did singlehandedly “fixing the deficit” become a necessary criterion for each and every tax and budget policy proposal? David Fahrenthold and David Nakamura invoke this strange new rule in an article in today’s Washington Post.

“Neither [the Paul Ryan budget nor the Buffett Rule] will fix the deficit problem anytime soon: The GOP’s proposal wouldn’t balance the budget until 2040. By itself, the Buffett Rule wouldn’t do it ever.”

There is a lot wrong in this sentence.

First, comparing a comprehensive budget proposal to a single tax reform is an apples-to-oranges (or apple-to-bushel-of-apples) comparison. Second, the Ryan budget doesn’t actually balance the budget until … well ever. The too-often cited Congressional Budget Office’s long-term analysis evoked here is based on the false premise that revenue will magically hold at 19 percent of GDP, ignoring the trillions of dollars of budget-busting, gimmicky tax cuts (Ryan assures that this money and more can be made up by “broadening the base” of taxation but offers no specifics). Lastly, nobody invokes the Buffett Rule as the single instrument for balancing the budget—very few fiscal policies have that reach. Take an extreme example: Immediately abolishing the Department of Defense would not balance the budget within a decade, relative to current policies. That’s besides the point–cutting more than $7 trillion in non-interest spending over a decade would produce a sustainable fiscal trajectory (ignoring sizable second-order cyclical budget effects from the massive hit to aggregate demand). The trajectory for debt held by the public is the relevant metric of fiscal sustainability, not a binary for budget deficit/budget surplus.

Fahrenthold and Nakamura double-down on brushing off non-trivial budgetary savings, also missing the broader fiscal implications of the Buffett Rule: “Even if it passed, the [Buffett Rule] would not likely make a serious dent in the country’s deficit. It might add up to $162 billion over 10 years. The national debt grows fast enough to wipe that out within two months.”

So $162 billion in budgetary savings is something to laugh at? I’ll remember that next time conservatives propose to reduce the deficit by drug-testing unemployment insurance recipients, eliminating the National Endowment for the Arts, or defunding Planned Parenthood. To be more concrete, these savings would more than supplant the draconian $134 billion 10-year cut to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamps) proposed in the Ryan budget.

Further, the criticism that $162 billion is dwarfed by this year’s budget deficit is doubly misleading. For one, budget deficits have swelled in recent years because the economy is so weak. Comparing a 10-year cost-estimate of just about anything to the sizable but cyclical budget deficits spurred by the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression is unhelpful. Further, policymakers shouldn’t be concerned at all with reducing this year’s budget deficit; serious concerns about budget imbalance are about stabilizing debt in the medium and long-term, after the economy has recovered. Revenue from implementing the Buffett Rule would be weighted toward the out years, where savings will be larger relative to projected budget deficits than today, and that’s exactly how it should be.

Senator Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) echoed this very same misguided sentiment in a statement on the Buffett Rule: “The President’s so-called Buffett Rule is a dog that just won’t hunt. It was designed for no other reason than politics – there is no economic rationale for it. It would do little to bring down the debt…” This specious “if it doesn’t fix the entire problem, it’s not worth doing,” objection to raising more revenue and increasing tax progressivity was similarly trotted out in defense of the upper-income Bush-era tax cuts, the expiration of which would raise $849 billion over a decade. Luckily, Jon Stewart decided to smack at this bad argument. He probably won’t have time to go after this latest Washington Post article, which is a shame because it’s about as silly.

It’s true, the Buffett Rule won’t lower unemployment by itself (but it’s still worth doing)

The National Journal’s Jim Tankersley correctly points out that the Buffett Rule will not, by itself, solve the most pressing economic problem in front of us: the still far too high unemployment rate. Then, bizarrely for Beltway writers talking about the unemployment rate, he also correctly points out what would help lower this rate: increased aggregate demand.

But it doesn’t follow from here that the Buffett Rule is bad policy. In fact, for those who think that we should aggressively target a lower unemployment rate in the near-term while also simultaneously locking in commitments to reduce longer-run budget deficits, the Buffett Rule should be seen as a huge win. However, this is if (and only if) it is accompanied in the next couple of years with aggressive fiscal job-creation measures such as infrastructure spending, aid to states and local governments, and making sure that existing fiscal support (unemployment insurance, food stamps, targeted tax cuts) does not fade away.

Of course, I’m not one of those who think we must only pair near-term measures to lower unemployment with longer-term measures to close the deficit. I’d be happy to take the near-term measures, well, in the near-term and deal with longer-run issues when we can.

And, in fact, it would be optimal from a pure economics perspective to finance aggressive near-term fiscal support with debt in the short-term, rather than (even Buffett Rule-rule style) tax increases. But given the near-universally misplaced D.C. obsession with closing budget deficits, always and everywhere, financing job-creation efforts with the Buffett Rule and other high-income tax cuts makes plenty of sense to me.

Permanent tax increases on upper-income households provide very little drag on near-term recovery, whereas the intelligently-directed fiscal supports noted above have quite large effects. Moody’s Analytics chief economist Mark Zandi pegs the fiscal multiplier (i.e., the increase in GDP stemming from a dollar of spending increases or tax cuts) for infrastructure spending at $1.44, versus $0.35 for permanently extending all the Bush-era tax cuts. This implies that a dollar of infrastructure investment financed by a dollar of permanent tax increases would generate on net $1.09 in economic activity (a balanced-budget-multiplier).

Tankersley concludes his piece, “If the Buffett Rule was a serious pitch to help the jobless, it would deal with one of those main drivers of unemployment. It would boost persistently weak aggregate demand or incentivize business investment.”

Nobody agrees with this general sentiment more than us at EPI – really. But given the mad rush to cut deficits, throwing the Buffett Rule on the table seems awfully smart. It minimizes short-run damage to jobs and growth from reducing the deficit, it can be paired with effective fiscal support to yield extra economic activity and jobs without increasing the deficit, and it locks in a policy that will make our tax system fairer, more efficient, and capable of generating the revenue needed to fund government in the long-run.

Panel on tax fairness and reform helps address common misperceptions

I had the opportunity to participate in an Americans for Democratic Action panel discussion yesterday on tax fairness. The panel, called “Tax Equity: Paying Fair,” was moderated by John Nichols of The Nation and included panelists Bob McIntyre of Citizens for Tax Justice, Mike Lapham of United for a Fair Economy, Dean Baker of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, Elspeth Gilmore of Resource Generation, and Chuck Marr of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. It was an honor to participate alongside them.

The panel covered a number of topics, including the Buffett Rule, the Paul Ryan budget, the George W. Bush-era tax cuts, the equalization of tax rates for capital and labor income, corporate tax dodging, and a financial transactions tax. But beyond the wonkier side of tax policy, Baker raised an important point that merits highlighting. He talked about people’s misperceptions regarding how much federal income tax they actually pay—in other words, confusion of marginal tax rates for (lower) effective rates. For example, the second highest tax bracket (33 percent) is assessed for single filers on taxable income between $174,400 and $379,150 (for the tax year 2011 returns due April 17). If you are a single filer with $180,000 in annual taxable income, you do not pay 33 percent on all of your income—as is widely misperceived. You would pay 33 percent only on your total income (less the personal exemption, deductions, and exclusions) exceeding $174,400. In this case, only $5,600 of your total income would be subject to the 33 percent rate.

I was really glad to see Dean Baker bring up the point of marginal versus effective tax rate confusion, because I think widespread misperception unduly adds to public fears of returning to Clinton-era tax rates. Raising the top tax bracket from 35 percent to 39.6 percent will only very marginally impact what high earners pay. Most Americans simply do not make enough to be subject to top income tax rates; President Obama’s proposal to extend the Bush tax cuts for households with less than $200,000 ($250,000 for joint filers) in adjusted gross income—letting only the top two rates expire—would result in a tax increase for only 2.1 percent of households. I was hoping to make a similar point to Baker’s, had there been more time for that in our conversation. I was recently struck by a portrayal of tax rate perceptions and reality in Bruce Bartlett’s new book on tax reform, The Benefit and the Burden. Bartlett draws from a CBS News/New York Times poll from April 14, 2010, that asks the following:

On average, about what percentage of their household incomes would you guess most Americans pay in federal income taxes each year: less than 10 percent, between 10 and 20 percent, between 20 and 30 percent, between 30 and 40 percent, between 40 and 50 percent, or more than 50 percent, or don’t you know enough to say?

The results are depicted below. The respondents indicated they believed 5 percent of Americans pay less than 10 percent of their income in federal income taxes. The reality is 86.5 percent of Americans actually did, in 2010. Additionally, respondents indicated they believed 38 percent of Americans pay over 20 percent of their income in federal income taxes. The reality: Only 0.6 percent of Americans pay over 20 percent of their income in federal income taxes.

| Tax percentage/income | Perception | Reality |

| Less than 10% |

5% |

86.5% |

| 10-20% |

26% |

12.9% |

| 20-30% |

25% |

0.6% |

| 30-40% |

10% |

|

| 40-50% |

2% |

|

| More than 50% |

1% |

|

| Don’t know |

31% |

n/a |

Source: The Benefit and the Burden, 2012

Thank God for trial lawyers

For many years, Corporate America has been waging a campaign to vilify the lawyers who bring suits against them. After decades of knowingly exposing workers and consumers to potentially fatal asbestos, the companies that had profited tried to kill asbestos litigation when lawsuits began to bankrupt them. When tort suits helped workers get real compensation for disabling injuries from unsafe machinery, the corporations moved to bar the suits. When class-action lawsuits proved to be an effective way to bring claims against giant corporate wrongdoers, Congress passed new laws to make such suits more difficult. And when doctors and hospitals began to pay heavily for medical malpractice, they started campaigns in every state and in Congress to limit the damages that could be awarded against them.

All of the harm that corporations and other actors have done to the public—the subjects of so much litigation—could have been better controlled by regulation with real teeth and effective enforcement. Asbestos could have been banned decades ago, as it was in most of Europe. Machines could have been required to have better lock-out mechanisms and better guarding as they were manufactured, to ensure that employees would never be maimed or killed. Drug tests could have been required to be conducted with more independence and transparency, with conflicts of interest prevented. And hospitals could be regulated to prevent unnecessary infections, misadministration of medicines, and surgery on the wrong patient or wrong limb.

But our political culture resists regulation, and even when we have regulation, the government does not always enforce it energetically. Thus, we do have a law and regulations that forbid for-profit employers from employing workers without paying them the minimum wage. And those regulations forbid the employment of students or anyone else as interns (except in very limited circumstances) without paying the minimum wage. The Department of Labor, however, does almost nothing to enforce the law in this area. Moreover, the token penalties in this and most areas of labor law lead companies to treat them as a cost of doing business.

So I was delighted to see the trial bar take this issue on, with a highly respected New York law firm suing Fox Searchlight and Hearst Corporation for failing to pay various employees the corporations called “interns,” including college graduates and even a CPA.

The effect of these suits has been salutary! Already, the media report that other employers have taken notice and law firms are now advising clients not to break the law. One USA Today headline read, “Fewer Unpaid Internships to Be Offered.”

I hope the headline is accurate, and if it is, it will be due to the efforts of Outen and Golden, LLP. The New York law firm is doing the work our government ought to be doing.

Thank God for trial lawyers.

Robert Lawrence misleads the New York Times on manufacturing

Last week, Eduardo Porter wrote in the New York Times’ Economix blog about a response he received on his recent piece on manufacturing from Robert Lawrence of the Kennedy School. Porter should have dug into the topic further because what Lawrence wrote was rather misleading. Here are Porter’s words:

“Prof. Robert Lawrence from Harvard makes an interesting point in response to my Wednesday column about our misplaced hopes in manufacturing as a source of new jobs: even if every single thing we bought was “made in America” — if we stopped multinationals from outsourcing production to China and closed our doors to imports — even then, manufacturing employment would lag.

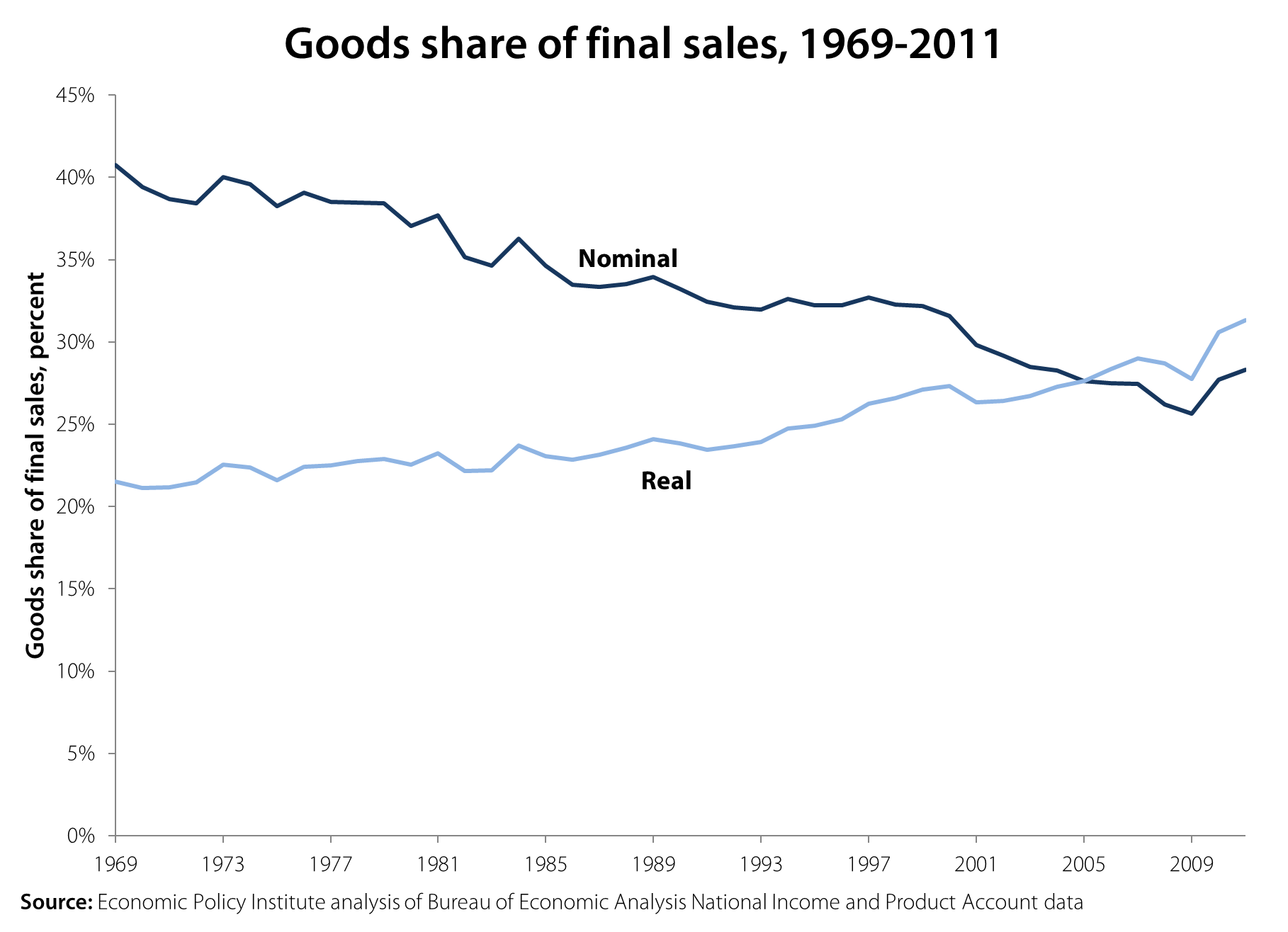

The reason is simple: we are spending less and less on goods and more and more on services. In 1969, American consumers were allocating half of all their spending on consumption to goods. By 2010, that share had fallen to one-third.”

Lawrence clearly wants people to believe that manufacturing jobs are declining because “we” just don’t buy much manufactured stuff anymore, or, in economic terms that there’s less demand for goods now than in the past. But that’s wrong, for a couple of reasons. First, goods are not only produced for household consumption, they are also produced for business and public investment, and for export. Second, and more importantly, the prices of goods have fallen relative to other types of products, so the goods share of total nominal (not inflation-adjusted) spending might fall, but the share in real (inflation-adjusted) spending might not follow. Or, to put it simply, people might have more TVs in their homes than ever before even while the share of their total income they spend on TVs has fallen. But, nobody would describe this state as a declining demand for TVs.

The following graph shows the share of goods in final sales of domestic products (the Bureau of Economic Analysis provides data on major types of products, dividing final sales into goods, services and structures. See NIPA Tables 1.2.5 and 1.2.6). The goods share of final sales in nominal terms did fall from 40.8 percent in 1969 to 28.3 percent in 2011, a roughly 30 percent decline in relative spending. However, the share of goods in real final sales actually rose 50 percent from 21.5 percent in 1969 to 31.3 percent in 2011. This means that the economy was even more goods-intensive in 2011 than in 1969 and that it was not a relative decline in the demand for goods that caused the shrinkage of manufacturing employment.

In the end, manufacturing employment is a horse race between demand for manufactured goods (which boosts jobs) and productivity (which, all else equal, means fewer jobs are needed in the sector). One thing that this analysis should remind us of is that even faster productivity has its upside: As prices fall because productivity rises in this sector, people demand more manufactured goods.

It should be noted, however, that neither Porter nor Lawrence denies that lowering the trade deficit would boost jobs. Rather, Porter says that even without any imports, manufacturing employment would lag. Lawrence, meanwhile, says that even without a trade deficit, goods employment would fall. In reality, closing the trade deficit would provide millions of jobs and boost the economy. For instance, my colleague Robert Scott has shown that growing trade deficits with China eliminated 2.8 million U.S. jobs between 2001 and 2010 alone, including 1.9 million jobs displaced from manufacturing. Similarly, correcting the currency imbalances with China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, and Malaysia could add up to $285.7 billion (1.9 percent) to U.S. GDP, create up to 2.25 million jobs over the next 18 to 24 months (most in manufacturing), and reduce U.S. budget deficits by up to $71.4 billion per year.

Moreover, as Scott’s recent blog post notes, the recent recession was especially hard on manufacturing (we lost 2.3 million jobs between 2007 and Jan. 2010) and we can get those jobs back in a robust recovery.

So, sure, manufacturing employment will not return to 25 percent of employment. Nevertheless, we can gain a lot of manufacturing jobs by strengthening the recovery and through appropriate trade and currency policy. This would provide millions of good jobs, aid many communities, and be good for the nation. No head-fakes about household consumption shares should distract us from these facts.

Latinos versus the Census Bureau: When racial categorizations clash

People create races, not nature. Different societies tend to have different systems of racial categorization. Even within the same society, there can be significant changes in racial categorization over time. We can get a sense of this from the fact that U.S. Census Bureau has made changes to the rules for racial classification system in nearly every census.

The guidelines for the 1940 Census (the full data of which was recently released to the public) instructed enumerators that “any mixtures of white and nonwhite blood” should be classified as nonwhite. Additionally, people of “mixed Negro and Indian blood should be reported as Negro” while “other mixtures of nonwhite parentage should be reported according to the race of the father.” These rules only make sense when embedded in the specific U.S. political economy of slavery and Jim Crow.

Today, in post-Civil-Rights-era America, individuals define their own race, not the Census enumerators. Also, in response to lobbying for multiracial categorization, since 2000 the Census Bureau has allowed individuals to select more than one race. In 1940, multiracial categorization in Census data was not possible.

Over the past few decades, the United States has seen a significant increase in the Latino population. Many of these Latinos are immigrants from other countries with other systems of identity and racial classification. These systems of classification may be in conflict with the official directives of the Census Bureau.

According to the Census Bureau, being Hispanic or Latino is an ethnic classification, not a racial classification. For perhaps as much as half of the Latino population, however, Latino is a racial category. A new survey from the Pew Hispanic Center illustrates this fact. When asked “Which of the following describes your race?”, 25 percent of Latinos answered “Hispanic or Latino.” Another 26 percent chose “Some other race”–rejecting the Census-Bureau-recognized racial categories of “white,” “black,” and “Asian.” While some of these “Some other races” may have been looking for “American Indian,” it is doubtful that all or even a majority of them were. They were looking for some racial category that the Census Bureau does not offer.

For many Latinos, “Latino” is understood as a racial category or as something other than an ethnic category in the sense that the Census Bureau intends. The idea of a cultural racial category is not an uncommon one. Nazi Germany, notoriously, institutionalized the category of a Jewish race. In Japan, there is the idea of a Japanese race which would distinguish them not only from non-Asian groups, but from other Asians as well. Groups that are conceptualized as cultural in the United States can be conceptualized as racial elsewhere.

Recently, NPR described George Zimmerman as a “white Latino,” but many of their listeners were confused by the term. This is interesting since according to data from the 2010 census 53 percent of Latinos are white.

The Pew Hispanic Center survey shows us that many Latinos see their group as something akin to a racial group. But the survey does not tell us how non-Latinos perceive and classify Latinos. Do non-Latinos perceive Latinos to be a separate race, an ethnic group, or something else? Latinos’ future in the United States depends not only on how they perceive themselves, but also on how others perceive, classify, and ultimately treat them. One hopes that a future Pew Hispanic Center survey will ask these questions.

Memo to the Times: Hold the funeral march for U.S. manufacturing

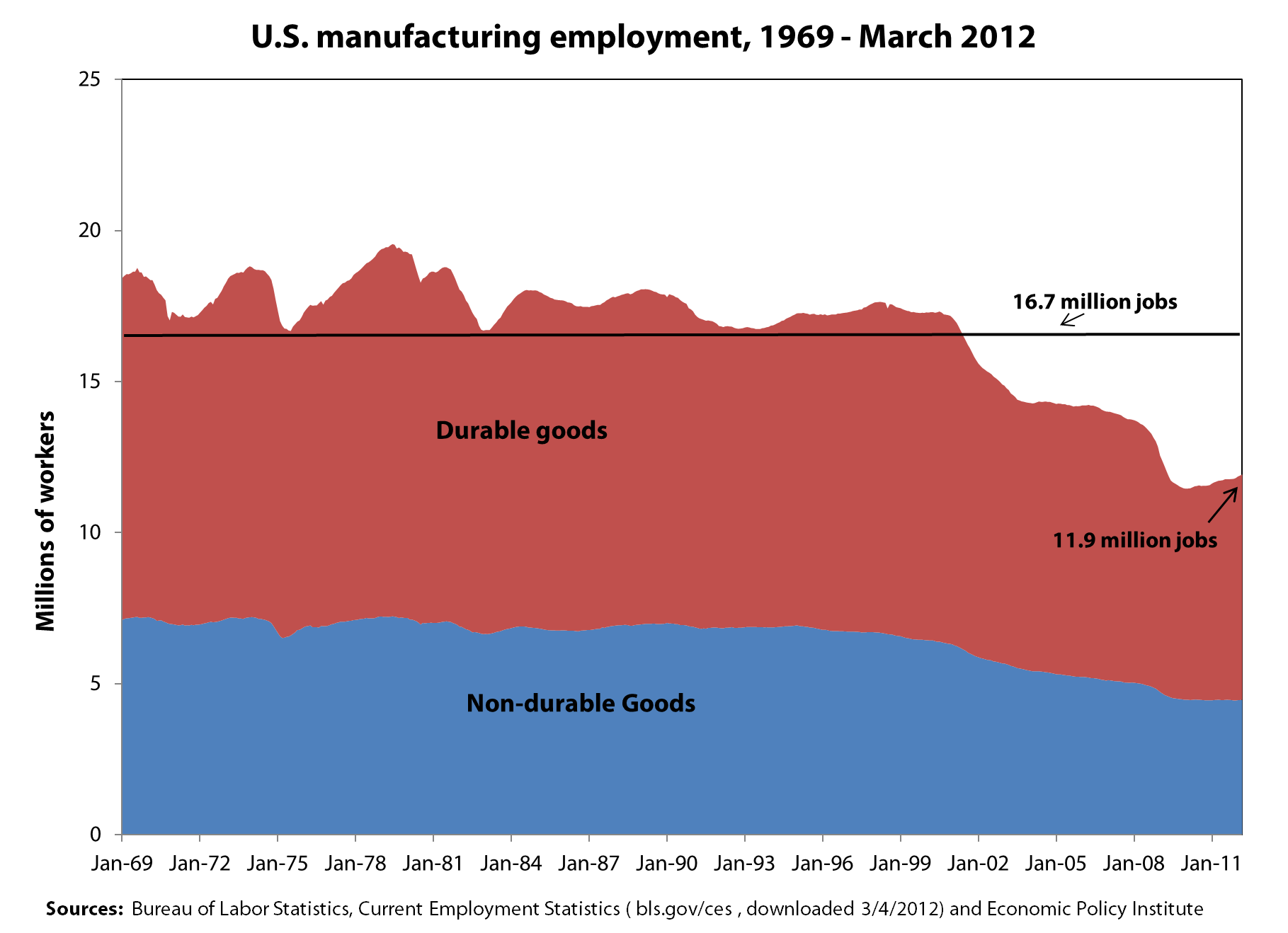

A recent commentary by Eduardo Porter in the New York Times claims that a “revolution in manufacturing employment seems far-fetched,” despite the recent recovery of manufacturing employment. Porter then proceeds to pound nails in manufacturing’s supposed coffin, claiming that “most of the factory jobs lost over the last three decades in this country are gone for good. In truth, they are not even very good jobs.” Perhaps not for a physicist like Porter, but manufacturing does provide excellent wages and benefits for many working Americans. And, with 11.9 million jobs today, U.S. manufacturing is very much alive and kicking.

Laura D’Andrea Tyson got the wage issue right in Why Manufacturing Still Matters, a post she wrote for the Times’ Economix blog in February. She notes that manufacturing jobs are “high-productivity, high value-added jobs with good pay and benefits.” According to Tyson, in 2009, “the average manufacturing worker earned $74, 447 in annual pay and benefits, compared with $63,122 for the average non-manufacturing worker.”1 Manufacturing wages and benefits are particularly attractive for workers without a college degree, for whom the alternative is often a job at low pay with no benefits.

Porter is also wrong to suggest that manufacturing employment has been on a downward trend for three decades (see graph below). In fact, manufacturing employment was relatively stable between 1969 and 2000, generally ranging between 16.7 million and 19.6 million workers. During this period, employment in big-ticket, durable goods industries such as autos and aerospace was more volatile than employment in non-durable goods. Starting from a peak in early 1998, U.S. manufacturing declined rapidly after the Asian financial crisis (which caused widespread devaluations in Asia), and total employment in both durable and non-durable goods began a sharp drop. This decline was associated with the rapid growth of the U.S. trade deficit, especially with China. Growing trade deficits with China eliminated 2.8 million U.S. jobs between 2001 and 2010 alone, including 1.9 million jobs displaced from manufacturing. Thus, U.S. job losses in manufacturing are really just a phenomenon of the past decade.2

Manufacturing has been hit with two distinct waves of job losses since 2000. Between 2000 and 2007, growing trade deficits were largely responsible for the loss of 3.9 million manufacturing jobs. In this period, employment declined in both non-durables (-20.3 percent) and durables (-19.8 percent) at similar rates. The great recession eliminated another 2.3 million jobs between 2007 and Jan. 2010 as the demand for cars and other manufactured goods collapsed. Employment in durable goods was hit especially hard by the recession, falling an additional 19.7 percent, while employment in durables fell 11.3 percent. However, since the end of the recession, employment in the two sectors has behaved in very different ways, as shown in the graph. Non-durable employment has remained essentially flat, adding only 5,000 jobs (0.1 percent) over the past 26 months, while durable goods industries have added 454,000 jobs (6.7 percent).

It does seem unlikely that the U.S. will recover many jobs in apparel or footwear. However, the non-durables sector also includes chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and petroleum refining. The U.S. exports large amounts of those commodities, and they certainly support the kind of high value-added, high-wage jobs Tyson described.

Durable goods industries such as aerospace products, machine tools, electronics, and motor vehicles and parts also support lots of exports, and those industries could grow with support of appropriate trade and industrial policies. Countries such as Japan and Germany have managed to support large and growing trade surpluses, especially in those sectors, because the vast majority of their exports are manufactured products. And, contrary to Porter’s assertions, they have lost a much smaller share of their manufacturing jobs than the United States. According to OECD statistics, between 2000 and 2009 (from peak to the trough of the recession), Germany lost fewer than 700,000 manufacturing jobs (an 8.3 percent decline). Japan lost 2.1 million (-17.4 percent), and the United States lost 5.7 million (-30.2 percent). The U.S. suffered nearly twice as much manufacturing job loss as Japan, and nearly four times as much as Germany.

Manufacturing employment in each of these countries has been hurt by the recession (although Germany, for example, did much more to prevent manufacturing job loss during the downturn), but the big difference is trade. In the German “Kurzarbeit,” or short work program, firms cut workers’ hours rather than make big layoffs, and the government helps make up the difference in workers’ paychecks (rather than paying unemployment compensation), thus limiting mass unemployment and stabilizing the economy. Growing trade deficits eliminated millions of manufacturing jobs in the United States, while growing trade surpluses helped support manufacturing jobs in Japan and Germany. It didn’t have to be that way, and we can recover lost manufacturing jobs in the future, especially in high-wage, durable goods industries. Read more

Social Security privatizer Pozen attacks public employee pensions

I don’t have any argument with the investment advice Robert Pozen and Theresa Hamacher gave readers of the Washington Post this past Wednesday. Diversification and investment in high-quality funds seems like common sense.

But the highly politicized trashing of public employee pension plans they indulge in along the way is based less on common sense than ideology. Pozen was an investment banker when George W. Bush appointed him to the President’s Commission to Strengthen Social Security. The commission launched Bush’s plan to privatize Social Security, which would have replaced the security of a guaranteed, regular monthly benefit check by making a large portion of their benefit contingent upon the returns from risky investments in the market. Why? Pozen and his fellow commissioners argued that the stock market historically yields much better returns on investment than the average worker gets from their contributions to Social Security:

“It is relatively straightforward to show that, for a given level of funding, a personal account system can offer higher total expected benefits than the current system.”

To illustrate, the commission helpfully provided a chart showing the average real returns (i.e., returns over and above inflation) of stocks from 1802 to 1997. For 20-year and 30-year holding periods, the real return was 7 percent, a nominal rate of about 10 percent. The implication was, of course, that these returns (having persisted for almost 200 years) would go on forever.

Shortly after the commission issued its report, the stock market crashed (a good lesson for a public that had been seduced by years of skyrocketing market values), and it crashed again, even harder, in 2008. Dean Baker points out that when Pozen was trying to cut public funding for Social Security and reduce benefits, he touted the potential returns of the market even though the price-to-earnings ratio was at historic highs (meaning that stocks were historically expensive to buy and unlikely to provide high returns going forward from that point).

Now, when price-to-earnings ratios are relatively low and stocks might be expected to do well for a few years, Pozen considers the market too risky for public pension plans. This seems contradictory (not to mention economically innumerate), but if one’s real goal is not to improve retirement security but to instead simply reduce benefits in public pension plans, there is no inconsistency.

Pozen argues that public employee pension plans are in crisis, or at least that a crisis is “looming.” He says we know this because even though plan liabilities are only about 4 percent of annual GDP according to standard accounting measures, those measures “rely on the existing, deficient rules for pension accounting” and understate the problem. They depend on the plans getting strong returns on their investments – generally about 8 percent in nominal terms and about 5 or 6 percent in real, inflation-adjusted terms. That of course, is less than the stock market returns Pozen and his fellow commissioners cited as the historic average for all 20 and 30-year periods. Pozen says a rate near 8 percent “seems unrealistic based on recent investment returns. Over the past 10 years, the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index has achieved only a 1.9 percent annualized return.” Remember, Pozen was arguing the exact opposite about the expected returns from stocks when it was (a) convenient to push his policy preferences, and (b) clearly wrong, as P/E ratios meant that stocks were more expensive (and hence had lower expected returns) back then.

Pozen wants public employee plans to use a discount rate of 4 to 5 percent, lowballing their expected investment returns and magnifying their potential underfunding. He joins Andrew Biggs at the American Enterprise Institute and a host of anti-government, anti-public employee conservative commentators whose twin goals are to reduce compensation for public employees and discredit government.

Whatever one thinks of Pozen’s investment advice, his advice on public policy has a dismal track record and deserves skepticism.

The worst recession in 70 years, not the worst recovery

In the Wall Street Journal last week, Edward Lazear penned a column titled The Worst Economic Recovery in History. Let’s take this claim to the data. The figure below directly compares job growth in the recovery from the Great Recession (labeled “2007 recession”) to job growth in the recoveries from the three prior recessions:

It’s clear from the figure that jobs fell much further and faster during the Great Recession than in previous recessions. But looking to the right of the dotted line, we see that job growth in the current recovery is actually stronger than job growth in the recovery following the recession of 2001, and not that much weaker than the recovery following the recession of 1990. The recovery following the 1981 recession outpaces all three by far, but that should not be a shock. The 1990, 2001, and 2007 recessions were all associated with financial crises (savings and loan crisis, dot-com bubble, and housing bust, respectively) and it’s obvious by now that recoveries from such recessions require much stronger medicine. The 1981 recession, by contrast, was largely caused by the Federal Reserve Board raising interest rates to curb inflation. This gave the Fed lots of room to lower rates to provide a boost from interest-sensitive goods, (namely housing and durable goods,) leading to strong job growth. With interest rates currently near zero, that lever has not been available in the Great Recession and its aftermath. (As an aside, it’s worth mentioning the extraordinarily fast growth of government spending that buoyed the 1981 recovery.)

The above figure underscores that the key difference between the job situation at this point in the economic recovery, compared with the same point in the last two recoveries, is the length and severity of the recession that preceded them. In other words, it’s not that job growth in the current recovery is uniquely terrible—it is pretty much in line with the weak recoveries following the last two recessions—it is the Great Recession (and in particular the job loss from Sept. 2008–June 2009) that was uniquely terrible.

Of course, this in no way lets today’s policymakers off the hook; the nation’s labor market remains incredibly weak and the current pace of job growth will needlessly condemn millions of Americans to joblessness for years to come. The key problem in the current economy is depressed demand for goods and services, which (since workers provide goods and services) translates into depressed demand for workers. Effective responses, however, have been hamstrung by destructive orthodoxy. I strongly agree with Lazear that we must “move to a set of economic policies that are aimed at growing the economy.” But his list of policies are either irrelevant (regulatory burden) or actually destructive (cutting government spending) to prospects for a rapid recovery.

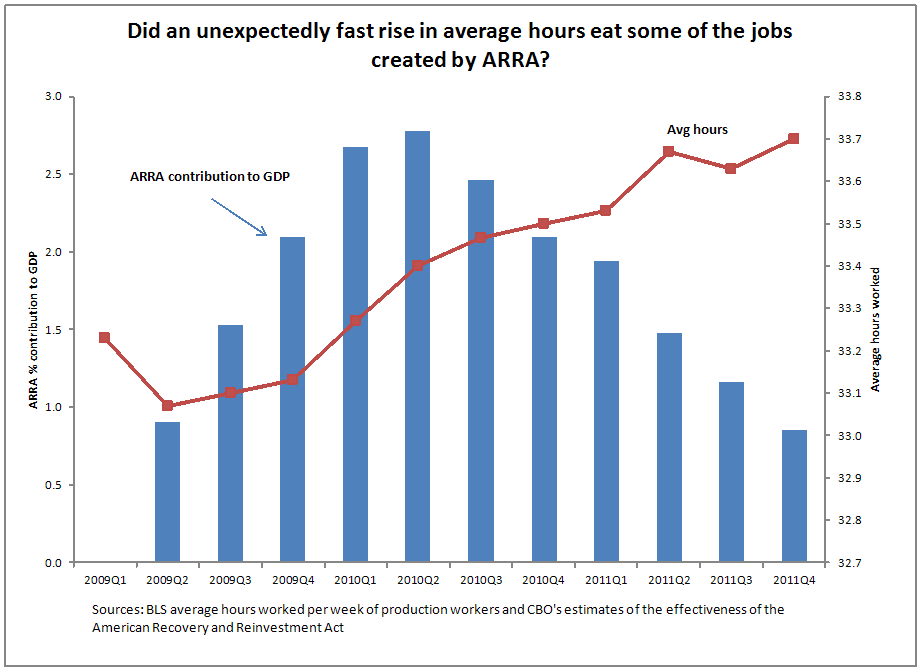

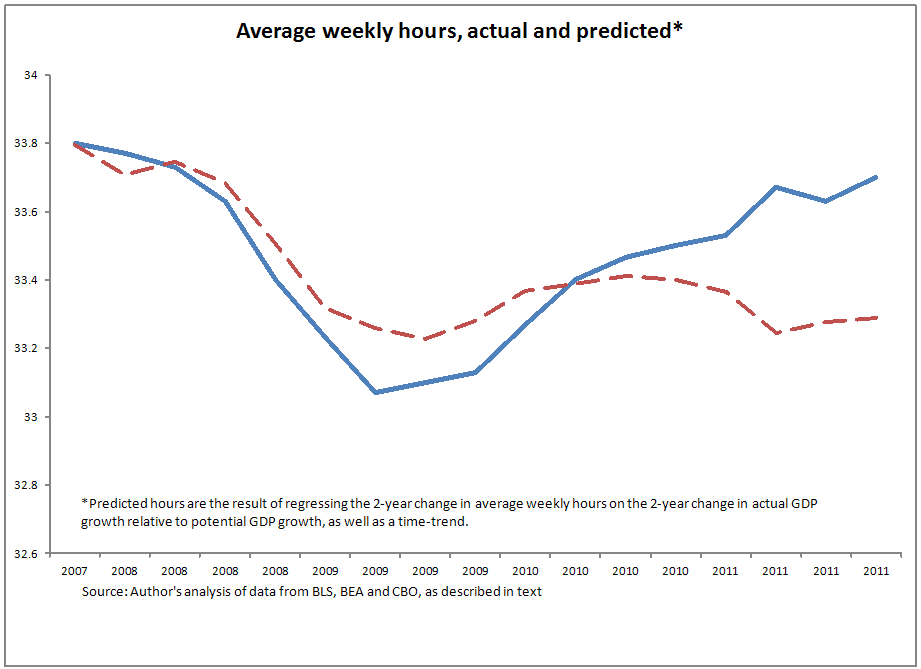

Were some of ARRA’s jobs eaten by rising hours?

Speaking of rising hours, it’s also interesting to note that the atypically large rise in average hours since the recession’s trough happened to coincide with the period during which the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) was providing its peak boost to economic activity (see the figure below).

Between the first half of 2009 and first half of 2011, ARRA boosted GDP by roughly 1.3 percent. All else equal, this should have been associated with employment in the first quarter of 2011 that was roughly 1.5 million higher and unemployment that was a full percentage point lower by the first quarter of 2011 than would’ve happened without ARRA.*

But, over this same period, average hours worked rose by 1.4 percent. All else equal this implies that about 1.5 million new workers were not needed to absorb rising demand for labor.

To be clear, everybody who tries to translate additional economic activity spurred by ARRA (or anything else) into an increase in employment makes an adjustment for average hours increasing as the economy exits a recession and begins growing again – it’s a pretty typical pattern. But, as pointed out before, the rise in hours in the recovery following the Great Recession was atypically large and the GDP-to-employment translations may have been off because of it.

Of course, the most common criticism levied against ARRA by its critics was some version of the argument that “you guys saying it’s boosting the economy, but job-growth is really slow and unemployment is rising.”

So does the fact that rising hours may have crowded out potential new hires while ARRA was creating new demand then mean that the critics are right about the Recovery Act’s ineffectiveness?

Nope. ARRA created new demand for labor by boosting economic activity. Period. American workers as a group worked more and earned more money because of ARRA.

But it does tell us that we might not be so sure about how this new labor demand was allocated – and in fact it seems like more of it went to increasing the hours of incumbent workers and less went to increasing new hires than we may have thought.

One metric does not change, however: the estimate of full-time equivalent jobs created by ARRA. This measure holds hours constant by design. In short, this seems like the safest bet for having a solid assessment of what ARRA did. And for the record, at its peak during the last half of 2010, full-time employment was between 1 to 6 million higher because of ARRA, regardless of what was happening to hours.

The possibility that lots of the new employment opportunities created by ARRA were filled by increasing hours of incumbent workers rather than new hires may, of course, have meant that that ARRA was less effective from a political perspective. Had more of its boost to economic activity shown up in top-line labor market indicators like new hires and lower unemployment, its proponents (like me) might have had an easier job demonstrating just how important it was.

*All numbers on ARRA’s effectiveness in this post come from the CBO

Washington Post misdiagnoses causes of retirement insecurity

The Washington Post published a story earlier this week by Jia Lynn Yang that had all the information needed to conclude that the 401(k) isn’t working out. She reports that the 401(k) has caused serious stress for working Americans and cites some scary financial data from the Center for Retirement Research. Since Congress created the 401(k) about 30 years ago, financial unpreparedness has gotten much worse: In 1983, researchers found that 31 percent of working age households were “at risk” of losing their standard of living when they retired; by 2009, it was 51 percent. The average worker who retires should have more than $300,000 in their 401(k) account, but in 2007 – even before the markets crashed and wiped out trillions in savings – the average person about to retire had only $78,000. The story didn’t mention that the cumulative underfunding of retirement accounts is nearly $7 trillion.

But instead of fingering the 401(k) as the cause of the stress and retirement insecurity most of us are facing, or even blaming Congress or the employers replacing pensions with a cheaper, badly designed personal account, Yang and her editors conclude that the fault lies with the many employees who are just too “clueless,” as Ms. Lang puts it, to deal with financial responsibility.

This lets the real villians off way too easily. Essentially, the big retirement-policy experiment of the past three decades has been replacing guaranteed pensions with … a tax cut, called 401(k)s. Since the 401(k) is failing so badly to achieve the most important goal our retirement system should have – the achievement of retirement security for most Americans – it should be replaced with something better, and we can put the money gained by closing the 401(k) tax expenditure to better uses. I also disagree with Yang’s statement that “even the program’s biggest critics concede that the system … is here to stay.” Not necessarily. The 401(k) is essentially a tax loophole that over-rewards the well-off for saving money they would have saved anyway. More than 70 percent of the tax deductions are taken by people in the top 20 percent by income. Every member of Congress claims we need to close tax loopholes and non-performing subsidies, and if tax reform ever happens, the 401(k) should be a fat target.

The article suggests that the 401(k)’s failures are really our own: ignorance, irresponsibility, making mistakes. It never mentions the effect on these accounts of the fees charged by plan administrators, investment advisors, and mutual funds, which can shave 25 percent off an account over a lifetime of work and investing. Yang never mentions that employers tend to put far less money into 401(k) plans than they do into pensions, that employers often reduce their contributions or freeze them altogether when times get tough, and that some employers make their contributions in company stock – often a poor choice and one that can lead to insufficiently diversified investments.

Yang does mention that it isn’t easy for individuals “to manage your investments intelligently through stock market highs and lows.” But I’m not sure she understands just how difficult it is, even for a former Assistant Secretary of the Treasury like Alicia Munnell, whom Yang quotes as saying “managing your own money is just horrible.” Market risk is out of one’s control, to a certain extent. To illustrate, Gary Burtless of the Brookings Institution estimated that a 401(k) participant retiring in 1974 would have a retirement income 64 percent lower than that of a worker who retired in 1999 if both workers contributed the same amounts over 40 years to a portfolio split equally between long-term government bonds and stocks (Burtless 2008). In short, two workers pursuing the exact same (and generally sensible) strategy achieve wildly different retirement income possibilities simply because of good or bad timing.

The tens of billions of dollars taxpayers are wasting to subsidize 401(k) savings each year would be much better spent on the more egalitarian, safer, and more nearly universal Social Security retirement system.

Business groups lobby to relax rules on much-abused guest worker program

The L-1 visa, a guest worker category relatively unknown to the general public, has received a lot of attention in the past couple of weeks from businesses that use it, news outlets that cover the technology sector, and now, from organized labor. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) is currently developing new interpretive guidance which has the potential to make this dysfunctional temporary work visa category dramatically better or dramatically worse.

The L-1 allows a multinational company to transfer personnel stationed abroad into the United States if it has a parent, subsidiary, or affiliate company located on U.S. soil. Such a company can petition to hire either a manager or an executive at its U.S. office (known as the L-1A subcategory), or a worker with “specialized knowledge” (L-1B). In 2010, nearly 75,000 L-1 visas were approved, and although they are available to companies in all industries, according to the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Office of Inspector General, “the positions L-1 applicants are filling are most often related to computers and IT.”

But there are a number of serious and systemic problems that have been identified with this visa category.

For example, the L-1 visa has no prevailing or minimum wage requirement, and no requirement that companies first check to see if there is an unemployed U.S. worker available for the job the L-1 worker will fill. There have also been documented cases of companies hiring an L-1 worker, forcing a U.S. worker to train the L-1 worker on how to do their job, and then firing and replacing the U.S. worker with the L-1 temporary worker. The fired worker is then prohibited from speaking a word of this to anyone as a condition of receiving a severance package. The employer is even allowed to pay home country wages to the foreign L-1 worker, which is likely to be tens of thousands of dollars less than what is paid to a similarly skilled U.S. worker. L-1 workers are also unlikely to complain about these low wages or any employer abuse that may occur, because if they speak up and get fired as a result, they are not allowed to take a job with another employer and become instantly deportable. This gives employers access to a lower-paid foreign workforce that has no bargaining power in the workplace.

The huge financial savings and unequal power relationship that employers enjoy when hiring L-1 workers – but especially L-1B workers who are not in executive or managerial positions – is the reason that the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and dozens of multinational companies are lobbying USCIS heavily, urging the agency to make it easier to hire L-1B workers. But that’s also exactly why Professor Ron Hira and I have harshly criticized the negative impact the visa has on the wages and employment opportunities of U.S. workers, and asked USCIS director Alejandro Mayorkas to refrain from expanding the L-1B category at the expense of decent-paying high-tech jobs in the United States.

On Tuesday, as reported in Computerworld, 20 unions that represent workers in high-tech occupations sent a letter to President Obama urging him to do the same. In addition, the IEEE-USA, the largest engineering professional society in the world (representing 210,000 engineers in the U.S.), sent a letter to Mayorkas expressing their concern about how the “L-1 visa program continues to be used in ways that exploit L-1B workers and adversely affect employment opportunities, wages and working conditions for U.S. citizen and permanent resident workers.” The IEEE-USA letter also reminds Mayorkas that the program should “exclude … outsourcing companies whose business models are based on workers acquiring skills, knowledge and contacts in the United States for the purpose of moving American jobs overseas.” Unfortunately, the data reveal that it does not.

The crux of what USCIS is considering has to do with better defining what constitutes a potential employee’s “specialized knowledge” – the legal requirement for the L-1B category. This definition has been problematic for a number of years. Multiple interpretations and guidance from the executive branch and judicial decisions have muddled and expanded the meaning, making it so broad “that adjudicators believe they have little choice but to approve almost all petitions.” This broadening of the legal standard makes it difficult for government officials to reject applications even when they believe them to be fraudulent.

No one disputes that multinational companies should have the right to bring in their brightest, best, most essential and talented personnel to help manage and run their offices in the U.S. But first, they have to show that the workers they bring to the U.S. are indeed highly skilled, and the government must implement basic protections that would prevent adverse effects on the wages and employment of U.S. workers. Since these requirements and protections are not yet part of the L-1 visa program, the L-1B category should not be allowed to grow or expand until they are in place. Instead, it should be curtailed drastically. The new USCIS guidance on L-1B specialized knowledge could help keep good jobs from being sent abroad and protect skilled high-tech workers in the United States – but only if Mayorkas and the Obama administration side with workers instead of the Chamber of Commerce and the high-tech offshoring industry.

Unemployment rising too fast, then falling too fast … going forward, it should (unfortunately) be just right

Has the unemployment rate fallen “too fast” given underlying output growth over the past 18 months? Applying a simple Okun-type relationship between changes in unemployment and the difference between growth rates of actual and potential GDP (or, changes in the output gap) would indicate so. Between the fourth quarter of 2009 and fourth quarter of 2011, the output gap shrank by less than 0.8 percent per year – which historically would only have been associated with a 0.4 percentage-point decline in the unemployment rate. Instead, the unemployment rate fell by 1.2 percentage points – or three times as much as our Okun regression might suggest should’ve happened.

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke noted this “too low” unemployment last week (so have Tim Duy and others). While there’s definitely some interesting stuff to examine here, we should first point out the one thing that nobody disagrees about. Going forward from now, the best estimate for what another 24 months of 0.8 percent average output gap reduction will buy us is the one provided by the classic Okun-style relationship: A very slight fall – about 0.4 percentage points – in the unemployment rate.

This cautionary tale about what to expect going forward is sometimes lost as people point out that the too rapid fall in unemployment recently is the mirror image of the too-rapid rise in unemployment in late 2009 and 2010. The graph below shows the actual unemployment rate and the one predicted by regressing two-year changes in unemployment on the two-year change in the output gap, as well the square of the change in the output gap (included to capture a non-linear effect pointed out by Zach Pandl at Goldman-Sachs; no link available, I’m afraid).

The graph clearly shows the too-rapid rise and fall of unemployment relative to predictions over the past couple of years. While interesting, this doesn’t change the most important thing that such an analysis tell us: If we want the unemployment rate to continue falling at the same rate that characterized the past year-and-a-half, we better see much faster GDP growth. As Bernanke said:

“However, to the extent that the decline in the unemployment rate since last summer has brought unemployment back more into line with the level of aggregate demand [note: i.e., recent too-rapid declines “making up for” earlier too-rapid gains], then further significant improvements in unemployment will likely require faster economic growth than we experienced during the past year.”

To be concrete, the Congressional Budget Office is projecting growth in potential GDP of 1.8 and 1.9 percent in 2012 and 2013, respectively. Mark Zandi of Moody’s Analytics is projecting actual GDP growth of 2.5 and 2.9 percent in those years, respectively. This means the two-year change from 2011 is right back at that 0.8 percent difference between actual and potential GDP growth that has characterized the last two years, which means we should expect unemployment to fall by only 0.4 percentage points over that time. This is what people should really know about unemployment changes going forward: absent serious measures to boost growth, they will be excruciatingly slow.

Lastly, it’s worth examining if there’s any odd economic development that might explain the too-rapid rise in actual unemployment between the second quarter of 2009 and the last quarter of 2010 – the time period that saw predicted unemployment begin lagging actual unemployment by more and more.

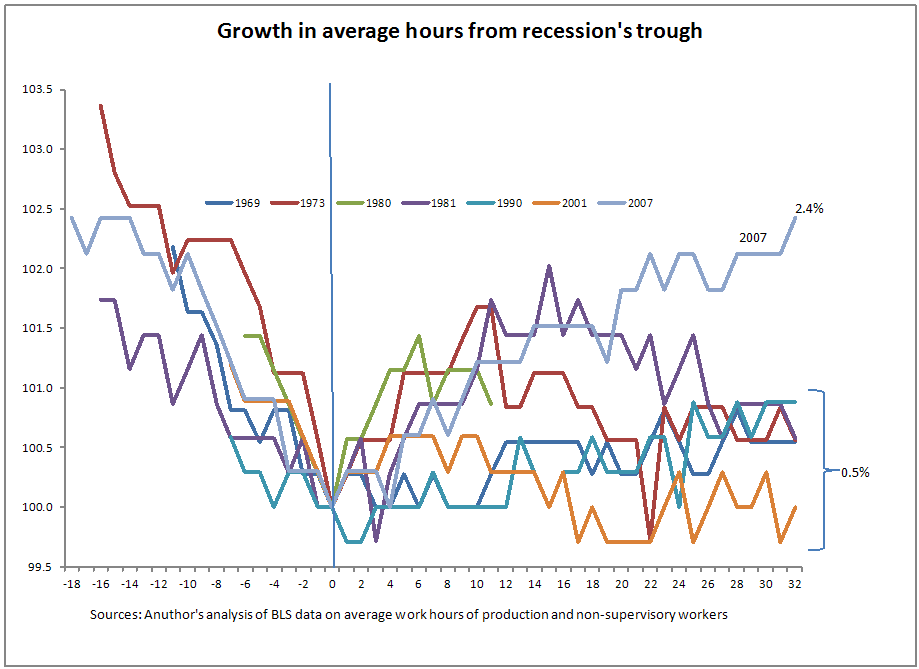

One pretty clear suspect is fingered in the graph below, which shows the rise in average hours across economic recoveries. For the most recent recovery, the index begins in the second quarter of 2009 (the official trough of the recession).

One can see clearly that the rise in average hours worked was atypically fast in the current recovery. In fact, compared to previous averages, the length of the work-week rose by about 2 percent. This is a big deal, representing about 2.3 million workers that did not have to be hired because rising demand was absorbed by rising hours of incumbents instead.

But shouldn’t this change in hours be soaked up in our Okun regressions by the output gap variable (since hours always tend to be procyclical)? Not this time. A regression of the change in hours on the change in the output gap (and a time trend) under-predicts the rise in hours between the second quarter of 2009 and second quarter of 2011 by nearly 2 percent. Between the second quarter of 2011 and the fourth quarter of 2011, the predicted rise is actually slightly greater than the actual rise.

So, what to make of all this?

First, going forward, the best predictor of what will happen to unemployment remains the Okun-based estimates based on GDP growth. Given that most estimates of GDP growth in the next couple of years do not see it beating growth in potential output by much, there is little reason to expect that the recent rapid declines in unemployment rates will continue.

Second, rising average hours might explain a lot of the too-rapid rise in unemployment in 2009 and 2010.

Lastly, given this large rise in hours, an aggressive program to promote work-sharing instituted during the recession could have been a big help in not allowing rising hours to soak up so much of the extra labor demand, and would’ve allowed the economic activity spurred by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act to translate more directly into higher head counts and lower unemployment. The Center for Economic and Policy Research’s Dean Baker had a good real-time proposal that would have been a real help. It’s not totally too late either – work-sharing pilot programs were included in the recent extension of payroll tax cuts.

Apple’s employees in China don’t work 70 hours a week because they want to

The most annoying responses to the revelations about Apple’s inhumane and exploitative factory pay and working conditions in China are the variations on the theme that the Chinese workers are grateful (or ought to be) to have the work and even the grueling overtime hours. “Sure, it looks like exploitation to Westerners, but really, Apple is lifting their living standards.” No. Apple is exploiting these young Chinese workers, grinding them down, forcing them to work for pay so low they can’t survive on it without working far beyond anything fair or reasonable – or even legal under Chinese labor law. And the workers don’t have a choice; they either work the overtime or they’re fired.

The Fair Labor Association, Apple’s hand-picked auditor, found that Apple’s most important supplier, Foxconn, works employees far beyond the hours permitted by Apple’s code of conduct (a maximum of 60 hours per week), let alone Chinese law, which limits work hours to 49 per week. The FLA reports that “in November and December 2011, 34% and 46% of the workforce respectively worked up to 70 hours per week.” Students and Scholars Against Corporate Misbehaviour (SACOM), a Hong Kong-based labor rights organization, has documented Foxconn employees working 140 hours of overtime a month.

Keith Bradsher’s recent “news analysis” in the New York Times, “Two Sides to Labor in China,” blamed the workers for these sweatshop hours and tried to portray them in a positive light. Bradsher wrote: “But one reason that workweeks of 60 hours or more have been possible at factories run by Foxconn and others is that at least some laborers already on the payroll have wanted the extra hours.”

Bradsher believes the employees have a choice about working 60-70 hours a week. He writes that “the added expense of hiring additional workers can make it cheaper to ask employees for extra overtime…” Ask? When Foxconn employees were throwing themselves out of dormitory windows, committing suicide in reaction to the harsh conditions at Foxconn, the company reduced work hours to 60 a week, but it didn’t give workers a choice about working them. As an Oct. 2010 SACOM report revealed, “Despite fatigue, workers cannot reject overtime work, because Foxconn requires workers to sign a Voluntary Overtime Pledge.”

Bradsher cites the FLA’s survey of Foxconn employees, 34 percent of whom reported they “actually wanted even more hours.” How can workers want more than 60 hours a week? Bradsher says they’re young and bored, have nothing better to do, “and were eager to make as much money as possible so as to return to their home villages.” He never suggests that their pay is so low they can’t survive working the legal maximum number of hours. But that is exactly what SACOM found in 2010 when it compared the cost of living in Foxconn’s factory cities with Foxconn’s pay. Without overtime, the average Foxconn production employee earned about 60 percent of what was required to meet basic needs. Today, after wage increases that have been offset by higher food prices and what Bradsher admits are “soaring rents,” 72 percent of Foxconn employees at Chengdu told the FLA their salaries did not cover basic needs.

So when Apple apologists tell you that “the Chinese are different, they want to work long hours,” don’t buy it. The richest corporation in the world is grinding its workers to the bone because it can get away with it, not because the workers want to live that way.

What to do about the eurozone?

Is the eurozone in recession? Eight consecutive months of rising unemployment indicate that the region could indeed be facing another economic downturn.

According to Eurostat, the European Union’s version of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the unemployment rate in the 17 countries that use the euro climbed to 10.8 percent in February, its highest level since the currency’s introduction in 1999. Seven eurozone countries have unemployment rates of more than 10 percent; in comparison, the United States’ unemployment rate is 8.3 percent. Past historical periods have also seen lower unemployment rates in the United States than in most of Europe, but the difference over the last couple of years is that joblessness in the eurozone is obvious collateral damage stemming from the embrace of fiscal and monetary austerity.

“Europe’s leaders just haven’t been nearly as committed [as U.S. leaders] to boosting demand with expansionary macroeconomic policies, either fiscal or monetary,” says EPI macroeconomist Josh Bivens.

“To be clear, the United States hasn’t provided adequate support to its economy and job market—but Europe has been even worse,” he continued.

In Spain, nearly a quarter of the labor force is unemployed, including more than half of workers under age 25. Spain’s plan to combat its troubles? A $36 billion austerity package passed by its new conservative government. As EPI has argued before, austerity measures are inappropriate solutions to unemployment crises. This is clearly the case in Greece, Ireland, and Portugal, all of which had to enact austerity measures as a condition of receiving bailouts. In these countries, austerity has compounded economic troubles and failed to improve staggeringly high unemployment rates.

The aftermath of clashes between protesters and police in Barcelona on March 29 by workers participating in a general strike against the Spanish government's economic reforms. (From Flickr Creative Commons by Sergio Uceda)

So how can the eurozone avert another crisis? Bivens thinks there are two separate questions that need to be answered. First, how are countries like Greece (and if we’re unlucky, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain) going to pay their debts (and how much of their debts will be written off by creditors)? Second, how are these same countries going to see growth in the next decade sufficient to ward off disastrous unemployment levels?

Bivens believes the second question gets much less attention—but is far more important.

“A key barrier to a country like Greece achieving growth in the coming decade is the lack of an independent monetary and exchange-rate policy,” says Bivens. “Greece absolutely needs to gain competitiveness in global markets as part of its medium-term macroeconomic strategy.”

He continued, “There are two paths there, exchange-rate adjustment or ‘internal devaluation’ [i.e., having Greek wages and salaries grow painfully slow for years]. The latter course is much more damaging; just look at Latvia, which fully embraced that strategy. The real lesson of the euro crisis is that all the tools of macroeconomic management need to be taken much more seriously than they have been.”

Nothing screams fiscal charlatan like a $4.5 trillion tax cut financed by gimmicks

Note: Since this blog post was first published, the Tax Policy Center has updated its revenue scoring of the tax provisions in the Ryan budget. Numbers and figures have been revised to reflect the more recent score.

House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan’s (R-Wis.) budget, which passed the House of Representatives on a party-line vote last week, continues to receive deserved criticism for its thoroughly dishonest treatment of the sweeping tax cuts it proposes. In a scathing critique, Paul Krugman honed in on its “fraudulent” nature: “The Ryan budget purports to reduce the deficit — but the alleged deficit reduction depends on the completely unsupported assertion that trillions of dollars in revenue can be found by closing tax loopholes.” William Gale of the Brookings Institution similarly concluded that “Ryan is gaming the system in creating budget estimates. … This is smoke and mirrors.

The contours of the Ryan budget’s tax cuts, as scored by the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center (TPC), are as follows:

Tax cuts:

- Cut and consolidate individual income tax rates to 25 percent and 10 percent brackets: $2.5 trillion

- Repeal the alternative minimum tax (AMT): $670 billion

- Repeal the surcharges included in the Affordable Care Act: $351 billion

- Cut the corporate rate to 25 percent and end taxation of multinationals’ foreign income: $1.1 trillion

Offsets:

- Allow Recovery Act expansion of refundable tax credits to expire: $210

- ???

= $4.5 trillion in revenue loss

Ryan’s budget blueprint describes these offsets this way: “Broaden the tax base to maintain revenue growth at a level consistent with current tax policy and at a share of the economy consistent with historical norms of 18 to 19 percent in the following decades.” And the budget totals in the Ryan budget reflect revenue averaging 18.3 percent of GDP over FY2013-22; similarly, the Congressional Budget Office’s long-term analysis of Ryan’s budget is predicated on the false assumption—provided by Ryan’s staff—that revenue will somehow total 19 percent of GDP over the long run (FY2025 and beyond).

This is simply dishonest. TPC’s analysis of the Ryan budget shows revenue averaging only 15.5 percent of GDP over FY2013-22, short of unspecified offsets.1 Yet Ryan wanted nearly $5 trillion in tax cuts and wanted revenue levels above 18 percent of GDP. Honest budgeting would force Ryan to choose between these two preferences (trade-offs being the whole point of budgeting). So Ryan chose dishonest budgeting, instead of changing the policy, he just changed the numbers.

We do know one thing about Ryan’s magic asterisk: it wouldn’t come anywhere close to raising revenue equivalent to roughly 3 percentage points of GDP over the decade (or roughly $6 trillion). For starters, he’s ruled out eliminating the preferential tax treatment of capital gains—the tax loophole most skewed toward the very top of the income distribution and estimated to cost $533 billion over the next decade, according to Citizens for Tax Justice. Furthermore, a new analysis by Jane Gravelle and Thomas Hungerford of the Congressional Research Service concluded that, “given the barriers to eliminating or reducing most tax expenditures, it may prove difficult to gain more than $100 billion to $150 billion in additional tax revenues through base broadening.” Adjusting for this range of feasible base broadening, the Ryan tax cuts would still require somewhere between $2.6 trillion and $3.2 trillion of deficit-financed tax cuts.2 Look at what happens to Ryan’s fiscal trajectory based on three alternative scenarios adjusting for: 1) no base broadening; 2) the low-end of feasible base broadening; and 3) the high-end of feasible base broadening.3

By 2022, public debt under the Ryan budget would be between $3.0 trillion (+19.6 percent) and $5.3 trillion (+34.2 percent) higher without the magic asterisk—a significant margin of dishonesty. This is not meant to breed fiscal alarmism or validate Ryan’s purported debt target; big budget deficits are inevitable in the aftermath of the Great Recession and premature fiscal retrenchment would jeopardize economic recovery. This is merely to prove that Ryan’s entire claim to fiscal responsibility rests on his tax gimmick.

With these tax cuts blowing the lid off of Ryan’s deficit reduction, his proposed evisceration of Medicaid, the social safety net, and public investments is exposed for what it really is: An attempt to gut the federal government and refund the tax bill to the highest-income households, not reduce the deficit. Some $5.3 trillion in non-defense spending cuts—nearly two-thirds of which come from programs for lower-income households—would roughly finance the $5.4 trillion cost of maintaining the Bush-era tax cuts, reduced estate and gift taxes, and the AMT patch. Ryan’s additional $4.5 trillion in tax cuts—two-thirds of which would go to households earning over $200,000—would be financed with a combination of increasing deficits and reducing tax expenditures other than preferential rates on unearned income, thereby shifting the distribution of the tax burden toward the middle class. Nothing screams fiscal charlatan like trillions of dollars worth of tax cuts skewed toward the affluent but financed by gimmicks and abdication of longstanding commitments to seniors, children, and the disabled.

1. TPC’s analysis is based on CBO’s Jan. 2012 baseline, whereas the Ryan budget is modeled from the March 2012 baseline. Adjusting TPC’s estimate of the Ryan plan for legislative and technical changes since the January baseline, the Ryan plan would see revenue average 15.6 percent of GDP over FY2013-22.

2. The $100 billion low-end and $150 billion high-end for base broadening are both set in FY2013 and held constant as a share of GDP thereafter.