Memo to the Times: Hold the funeral march for U.S. manufacturing

A recent commentary by Eduardo Porter in the New York Times claims that a “revolution in manufacturing employment seems far-fetched,” despite the recent recovery of manufacturing employment. Porter then proceeds to pound nails in manufacturing’s supposed coffin, claiming that “most of the factory jobs lost over the last three decades in this country are gone for good. In truth, they are not even very good jobs.” Perhaps not for a physicist like Porter, but manufacturing does provide excellent wages and benefits for many working Americans. And, with 11.9 million jobs today, U.S. manufacturing is very much alive and kicking.

Laura D’Andrea Tyson got the wage issue right in Why Manufacturing Still Matters, a post she wrote for the Times’ Economix blog in February. She notes that manufacturing jobs are “high-productivity, high value-added jobs with good pay and benefits.” According to Tyson, in 2009, “the average manufacturing worker earned $74, 447 in annual pay and benefits, compared with $63,122 for the average non-manufacturing worker.”1 Manufacturing wages and benefits are particularly attractive for workers without a college degree, for whom the alternative is often a job at low pay with no benefits.

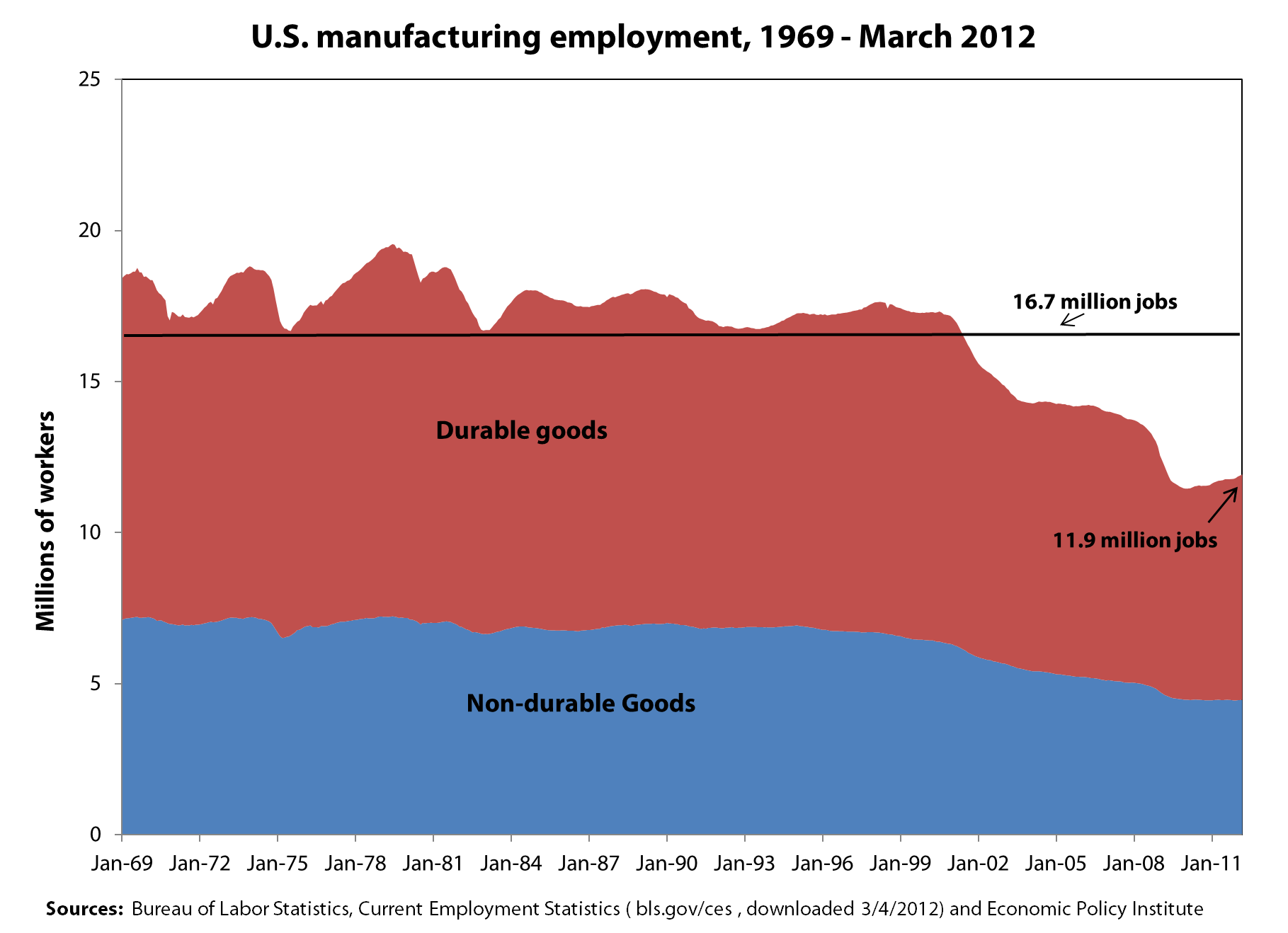

Porter is also wrong to suggest that manufacturing employment has been on a downward trend for three decades (see graph below). In fact, manufacturing employment was relatively stable between 1969 and 2000, generally ranging between 16.7 million and 19.6 million workers. During this period, employment in big-ticket, durable goods industries such as autos and aerospace was more volatile than employment in non-durable goods. Starting from a peak in early 1998, U.S. manufacturing declined rapidly after the Asian financial crisis (which caused widespread devaluations in Asia), and total employment in both durable and non-durable goods began a sharp drop. This decline was associated with the rapid growth of the U.S. trade deficit, especially with China. Growing trade deficits with China eliminated 2.8 million U.S. jobs between 2001 and 2010 alone, including 1.9 million jobs displaced from manufacturing. Thus, U.S. job losses in manufacturing are really just a phenomenon of the past decade.2

Manufacturing has been hit with two distinct waves of job losses since 2000. Between 2000 and 2007, growing trade deficits were largely responsible for the loss of 3.9 million manufacturing jobs. In this period, employment declined in both non-durables (-20.3 percent) and durables (-19.8 percent) at similar rates. The great recession eliminated another 2.3 million jobs between 2007 and Jan. 2010 as the demand for cars and other manufactured goods collapsed. Employment in durable goods was hit especially hard by the recession, falling an additional 19.7 percent, while employment in durables fell 11.3 percent. However, since the end of the recession, employment in the two sectors has behaved in very different ways, as shown in the graph. Non-durable employment has remained essentially flat, adding only 5,000 jobs (0.1 percent) over the past 26 months, while durable goods industries have added 454,000 jobs (6.7 percent).

It does seem unlikely that the U.S. will recover many jobs in apparel or footwear. However, the non-durables sector also includes chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and petroleum refining. The U.S. exports large amounts of those commodities, and they certainly support the kind of high value-added, high-wage jobs Tyson described.

Durable goods industries such as aerospace products, machine tools, electronics, and motor vehicles and parts also support lots of exports, and those industries could grow with support of appropriate trade and industrial policies. Countries such as Japan and Germany have managed to support large and growing trade surpluses, especially in those sectors, because the vast majority of their exports are manufactured products. And, contrary to Porter’s assertions, they have lost a much smaller share of their manufacturing jobs than the United States. According to OECD statistics, between 2000 and 2009 (from peak to the trough of the recession), Germany lost fewer than 700,000 manufacturing jobs (an 8.3 percent decline). Japan lost 2.1 million (-17.4 percent), and the United States lost 5.7 million (-30.2 percent). The U.S. suffered nearly twice as much manufacturing job loss as Japan, and nearly four times as much as Germany.

Manufacturing employment in each of these countries has been hurt by the recession (although Germany, for example, did much more to prevent manufacturing job loss during the downturn), but the big difference is trade. In the German “Kurzarbeit,” or short work program, firms cut workers’ hours rather than make big layoffs, and the government helps make up the difference in workers’ paychecks (rather than paying unemployment compensation), thus limiting mass unemployment and stabilizing the economy. Growing trade deficits eliminated millions of manufacturing jobs in the United States, while growing trade surpluses helped support manufacturing jobs in Japan and Germany. It didn’t have to be that way, and we can recover lost manufacturing jobs in the future, especially in high-wage, durable goods industries.

And we should. Manufacturing is important to our economy for a number of reasons, as pointed out by Tyson. First, manufactured goods make up 86 percent of our exports, and if we are going to balance our trade accounts (and support more domestic jobs) we must expand manufactured exports. Second, although manufacturing was only 11.7 percent of gross domestic product in 2010, it employed more than half of U.S. scientists and engineers, and accounted for 68 percent of business research and development spending and 70 percent of total R&D spending.

In addition, manufacturing punches above its weight—its impacts are felt broadly throughout the economy. Manufacturing is a huge consumer of commodities and of high-value, high-wage business services in sectors such as law, accounting, computer systems and management, and scientific and technical consulting. Overall, the value of manufacturing shipments (including purchased inputs) supported one-third of total U.S. GDP in 2010.

Recently, in another Times op-ed, Christina Romer, the former chair of President Obama’s council of economic advisors, argued against special treatment for manufacturers. My colleague Josh Bivens showed why Romer’s wrong and outlined the single most important step we can take to help manufacturers: ending illegal currency manipulation by China and other Asian countries. I have estimated that full revaluation by China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, and Malaysia could add up to $285.7 billion (1.9 percent) to U.S. GDP, create up to 2.25 million jobs over the next 18 to 24 months (most in manufacturing), and reduce U.S. budget deficits by up to $71.4 billion per year.

Greatly expanded investments in infrastructure, clean and renewable energy, worker training, and job creation could create additional demand for manufactured goods and fill the manufacturing pipeline with products that can be sold to the rest of the world. Reversing the decline of U.S. manufacturing employment over the past decades is certainly doable, but it won’t be easy or cheap. We must make the investments needed to make our economy more competitive and to bring unemployment down to its pre-recession levels, while also taking the steps needed to end currency manipulation and other unfair practices by our trading partners. These investments are well worth making.

The author thanks Ross Eisenbrey, Arin Karimian, and Phoebe Silag for helpful comments

Endnotes

1. These data appear to include wages and benefits for both production and non-production workers. Average weekly earnings (wages only) for production and non-supervisory workers in manufacturing were $40,800 per year in 2011, while the average weekly earnings for all other private sector production workers were $33,375. (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2012). Average hourly wages in manufacturing were slightly below those in the rest of the private sector. However, average weekly hours in manufacturing were 26.1 percent higher in manufacturing. Furthermore, average weekly earnings for all workers in manufacturing were 22 percent higher than those of production workers alone. In addition, pension, health, and other benefits are usually more extensive (and costly) in manufacturing than in other sectors (data reflected in Tyson’s wage estimates but not those shown here).

2. Porter examines international trends in manufacturing employment between 1991 and 2007 and claims that job loss was similar in the United States, Germany and Japan. However, this underestimates manufacturing job losses in the United States for two reasons. First, 1991 was the trough of a recession (as shown in the figure, so he picks a low starting point. Second, 2007 was the last year before the recession, so his analysis excludes the impacts of recession, which had a much larger effect on manufacturing employment in the United States than in some other countries.

References

Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Current Employment Statistics – CES (national).” Accessed 4/6/2012. Available at: http://bls.gov/ces/

Enjoyed this post?

Sign up for EPI's newsletter so you never miss our research and insights on ways to make the economy work better for everyone.