MEMORANDUM

TO: Alejandro Mayorkas, Director of United States Citizenship and Immigration Services

RE: USCIS Guidance on L-1B “Specialized Knowledge”

Dear Director Mayorkas:

We understand you plan on issuing new guidance for consular officers on what is required for foreign intra-company transferee workers to qualify for L-1B visas. According to reports, your office will be broadening the definitions of who qualifies for an L-1B visa, thus opening it up to greater use and reducing the level of scrutiny on petitions. We have examined the impacts and design of the L-1 visa program extensively and believe that it is being used in ways that harm American workers, provide little protection for L-1 workers, and speed up the transfer of high-tech, high-wage work overseas.

Abuses in the L-1 visa program are well-known, but have not been addressed

We commend USCIS for finally tackling the important issue of crafting better interpretive guidance for the definition of L-1B specialized knowledge. The USCIS Ombudsman Report for Fiscal Years 2010 and 2011 called on USCIS to “establish clear adjudicatory L-1B guidelines through the structured notice and comment process of the Administrative Procedures Act.”1 In 2010, the Economic Policy Institute made a similar appeal.2 In 2006, the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Inspector General published a report, Review of Vulnerabilities and Potential Abuses of the L-1 Visa Program.3 The title of an important section in the report warns that the “Definition of the Term ‘Specialized Knowledge’ May Not Be Sufficiently Restrictive.”4 The OIG outlines one of its main concerns with the definition of specialized knowledge, namely “[t]hat so many foreign workers seem to qualify as possessing specialized knowledge appears to have led to the displacement of American workers, and to what is sometimes called the ‘body shop’ problem.”5 Broadening the definition of specialized knowledge would exacerbate the concerns identified by the OIG.

Unfortunately, the American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA) and a number of employers who use the L-1 visa (including companies whose entire business model is designed to transfer jobs overseas) have recently written to you6 arguing for a broader interpretation of specialized knowledge. Such an interpretation would make it easier for someone to qualify as possessing L-1B specialized knowledge, even if they have ordinary skills and work in a position for which there may be unemployed U.S. workers available. The lack of any meaningful statutory or regulatory protections for U.S. workers in the L-1 program – in particular the lack of a prevailing wage rule or labor market attestation or certification process – would make this especially detrimental to the interests of U.S. workers during a time of persistently high unemployment. Even workers in most high-tech, engineering, and computer-related occupations are suffering from unemployment rates that are still double or triple what they were before the recession.

It is clear to us that the definition of L-1B specialized knowledge is already overly broad. As the OIG noted, it is so broad “that adjudicators believe they have little choice but to approve almost all petitions.”7 If everyone is specialized, then no one is. Therefore, there must be a clear and narrow distinction regarding what constitutes specialized knowledge. Expanding the definition, or interpreting it even more broadly than at present will result in putting downward pressure on the wages of U.S. workers employed in the main L-1B occupations and will keep unemployed U.S. workers – especially those who are highly educated and qualified for high-tech occupations – out of a job.

Broadening the definition will also help speed up the offshoring of high-paying jobs from the United States. Our research has shown that the leading users of the L-1B program are offshore outsourcing firms whose business model is to first hire L-1 workers to learn the work done by Americans, then to transfer that work overseas. The L-1 program was not intended to function in this way. Nevertheless, this blatant misuse of the program is legally permissible. As a result, the program is operating at the expense of American workers. Any guidance you issue that broadens the L-1B specialized knowledge definition will help facilitate the offshoring process and directly lead to the loss of good jobs in the United States.

In January 2011, the State Department issued a cable titled “Guidance on L Visas and Specialized Knowledge”8 to all consular posts, which wrestled with the difficulty of interpreting specialized knowledge. It has come to our attention that this additional guidance was requested because of an increase in fraudulent applications at certain posts. Nevertheless, we are unaware of specific steps that have been taken to remedy the problem. In fact, we are also unaware of any significant programmatic improvements to the many problems in the L-1 program that have been uncovered by the OIG, that have been discussed in congressional testimony,9 and reported on by multiple news outlets.10

Employers continue to have access to between 75,000 – 85,000 L-1 visas per year

Despite the demonstrated vulnerabilities of the L-1 program, its well-known susceptibility to abuse, and the negative impact on U.S. workers, Congress and multiple administrations have failed to act and remedy the problems. In the meantime, the program has been allowed to grow steadily.

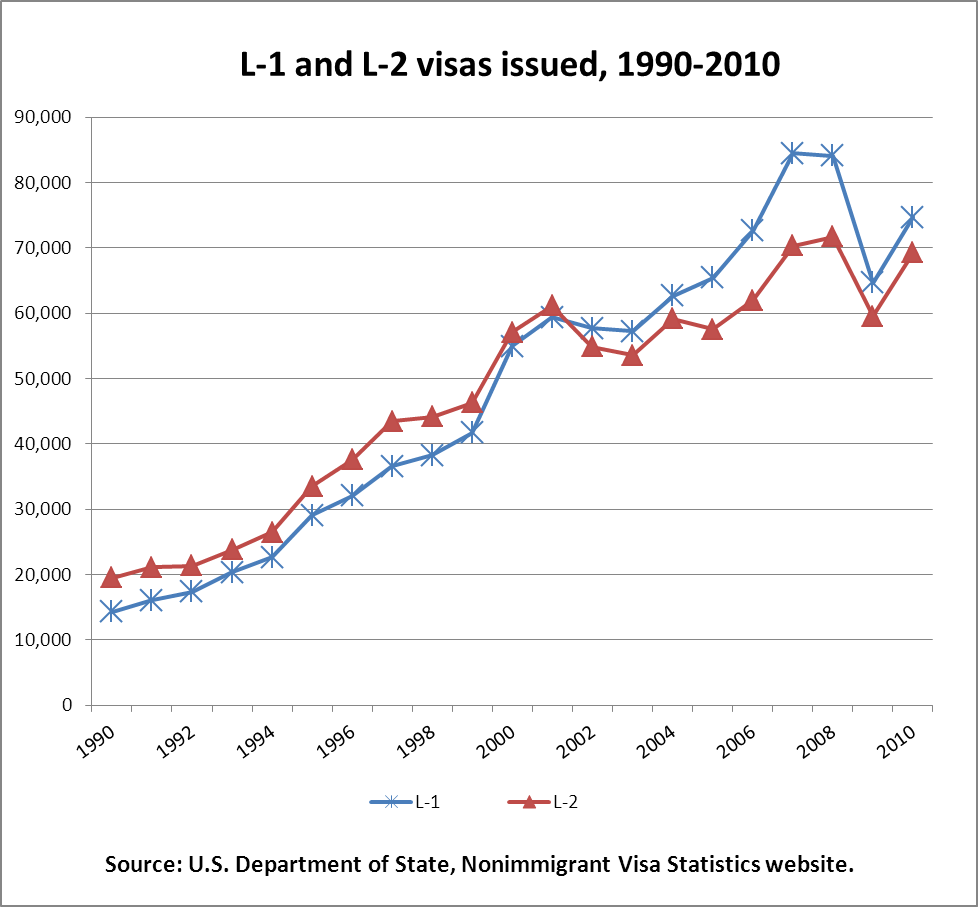

In Fiscal Year 2010, nearly 75,000 visas were issued in the L-1 category. The L-1 program increased rapidly and dramatically after passage of the Immigration Act of 1990 (IMMACT 90), peaking at over 84,000 during the two years that preceded the economic downturn. L-1 workers have been permitted to work for five or seven years, although this was recently changed to reflect the State Department’s visa reciprocity schedule.11 This means that there may be up to 500,000 L-1 workers currently authorized to work in the United States, but no federal agency is keeping track of how many are currently employed. The L-2 visa additionally allows tens of thousands of spouses and dependents of L-1 beneficiaries to reside and work in the United States for the same duration as the principal L-1 visa holder. In fact, nearly the same number of L-2 visas is issued each year as L-1 visas. The figure below illustrates the substantial growth of the L-1 and L-2 programs since the passage of IMMACT 90.

As these data illustrate, it is wildly inaccurate and not credible for employers to claim that they are being denied the ability to transfer their international personnel to work in the United States. Because there is no statutory limit on the number of L-1 visas that can be granted – unlike the H-1B visa which is used to hire foreign workers in similar occupations – the only limit on employers wishing to transfer their international employees to jobs in the United States is the validity of the petition.

Disturbingly, there is mounting evidence that the L-1 is being used either fraudulently or for inappropriate purposes. As the OIG report pointed out, Department of State Foreign Service officers are concerned that “software companies appear to be using the L visa to get around H quotas, and relocate individuals who may not meet the specialized knowledge requirement.”12 The vast growth in the program, combined with the fact that it is much easier and cheaper to obtain an L-1 visa than an H-1B visa, is likely to have contributed to an increase in fraudulent applications, and therefore to a corresponding reported increase in denial rates for petitions,13 as well as an increase in the percentage of petitions that are subjected to a request for evidence (RFE).

The figures below from the 2011 USCIS Ombudsman Report show the latest data on L-1A and L-1B petitions that have been subject to an RFE.14

The increase in L-1A and L-1B RFEs at the California Service Center has been significant, approximately doubling since 1995. But RFE totals at the Vermont Service Center for both L-1A and L-1B petitions have decreased since 1995 by approximately 35 and 14 percent respectively. And although we have not seen the raw data ourselves, the National Foundation for American Policy (NFAP) calculates that 63 percent of all L-1B petitions in FY 2011 were subject to an RFE.15

If the total number of RFEs has in fact increased, these data – in conjunction with the fact that no statutory or regulatory limit or “cap” exists on the size of the L-1 program – as well as the reports about the program’s misuse we outline above, suggest to us the likelihood that there has been an increase in fraudulent or at least inappropriate petitions submitted by employer-petitioners.

In fact, no evidence has been presented by the NFAP, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, AILA, or any other group that the rise in RFEs is not the direct result of a rise in unsupportable petitions. The March 22 sign-on letter to President Obama regarding L-1 visa policy16 neither presented nor referenced any evidence whatsoever that the increased level of scrutiny was not warranted. If such evidence exists, we ask that it be made public.

Multinational employers have complained to the USCIS Ombudsman that restrictive USCIS policy and adjudications “undermine U.S. competitiveness.”17 Those employers should keep in mind that the only valid reason a USCIS officer has to request more evidence from a petitioner or to ultimately reject the L-1 petition is because he or she is not convinced that the petition and its supporting documentation adequately satisfy the requirements of the law.

Finally, it should be noted that the vast majority of all L-1A and L-1B visa petitions are approved whether or not they were subject to an RFE. In fact, the lowest approval rate on record for L-1A petitions is 86 percent, while the lowest the L-1B approval rate has ever been is 73 percent.18

Impact of the L-1 visa program on the U.S. labor market

At a Senate Judiciary Committee Hearing in 2009, DHS Secretary Janet Napolitano said: “Our top obligation is to American workers, making sure American workers have jobs.”19

We urge you to take action that is consistent with the secretary’s “top obligation,” because from the perspective of U.S. workers, the L-1 program is disastrous. The L-1 programs have virtually no protections for American workers (or the foreign L-1 worker). Unlike the H-1B program, L-1 workers can be paid home-country wages, can directly displace American workers, and there’s no numerical limit on their use. Direct displacement of U.S. workers isn’t a theoretical possibility—there are cases of training your replacement that have been reported in the press—and based on our conversations with American workers, it’s clear that this is a widespread practice. And we know the largest sending country of L-1B workers is India, a country that has enormous wage differentials with the U.S. An employer may hire a software developer in India for a mere $7,000 per year, where a comparable American earns $75,000.

Unlike other nonimmigrant guest worker categories, reliable estimates about the program’s impacts on the competitiveness of U.S. businesses or the American workers and the U.S. labor market are impossible to calculate because USCIS and the State Department do not release data listing the exact occupations that L-1 and L-2 beneficiaries are employed in. In addition, no data are collected or published about the wages earned by these workers.

Basic data distinguishing between the number of L-1 visas that are issued to L-1A managers and executives or L-1B specialized knowledge employees are also unavailable to the public. This is important because L-1A workers are likely to be employed in better-paying, supervisory positions, while L-1B workers are more likely to be rank-and-file workers within a company, and thus more likely to compete directly with similarly skilled U.S. workers. The only bit of data released about this comes from the 2006 OIG report, which revealed the upward trend in L-1B issuance with a corresponding downward trend in L-1A. In 2004, for the first time, the number of L-1B visas issued was higher than the number of L-1A visas issued. If this trend has continued since 2005, as we suspect it has, it means that rank-and-file, ordinarily skilled L-1B workers make up an even larger proportion of the program than they did in 2004.20

Data revealing how many L-1 visas are issued through the streamlined “blanket” petition process and the names of the companies that are authorized to file blanket petitions are also unavailable, which is troubling because blanket petitions receive a reduced and minimal amount of scrutiny vis-à-vis individual, “regular” L-1 petitions.

These data gaps and serious lack of transparency reflect an unwillingness on the part of USCIS and the State Department to allow the public and researchers to make objective assessments about the impact of the L-1 visa program on the U.S. labor market, especially in terms of the offshoring of American jobs, wages, and unemployment in the high-tech sector. This disregard for the plight of U.S. workers should not be compounded by broadening the definition of L-1B specialized knowledge.

A spokesman for USCIS was recently quoted in a news article as saying the new policy guidance is based on active engagement, “with the public on the L-1B classification, including most recently at a forum at the end of January hosted by the Chamber of Commerce.”21 However, we know of key organizations that represent American workers as well as American companies which have not been heard. In fact, all of the major organizations we’ve contacted have said that they first heard about the new guidance in the press. We urge you to speak to all stakeholders, including groups representing American workers and American companies, before making this decision that will have serious ramifications on hundreds of thousands of high-wage, high-tech American jobs. We’ve already seen a huge flow of jobs overseas. There’s no reason why the Obama administration should put its thumb on the scale to ship even more jobs overseas. If the administration is serious about insourcing, as the president recently claimed at an event one of us attended in January, then the appropriate action to take would be to narrow and tighten – not expand and broaden – the definition of L-1B specialized knowledge.

Sincerely,

Daniel Costa, Esq.

Immigration Policy Analyst

Economic Policy Institute

Ron Hira, Ph.D., P.E.

Associate Professor of Public Policy

Rochester Institute of Technology

CC: The Honorable Hillary Clinton, Secretary of State; the Honorable Janet Napolitano, Secretary of Homeland Security; the Honorable Hilda Solis, Secretary of Labor.

Endnotes

1. United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), Ombudsman, Annual Report 2010, June 30, 2010, at 48, accessed March 25, 2012, http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/cisomb_2010_annual_report_to_congress.pdf; USCIS Ombudsman, Annual Report 2011, June 29, 2011, at 27, accessed March 25, 2012, http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/cisomb-annual-report-2011.pdf.

2. Daniel Costa, “Abuses in the L-visa Program: Undermining the U.S. Labor Market” (Washington D.C.: Economic Policy Institute, August 2010), at 16, accessed March 25, 2012, http://www.epi.org/page/-/pdf/BP275.pdf.

3. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Inspector General (DHS OIG), “Review of Vulnerabilities and Potential Abuses of the L-1 Visa Program,” OIG-06-22, January 2006, accessed March 25, 2012, http://www.oig.dhs.gov/assets/Mgmt/OIG_06-22_Jan06.pdf.

4. Id. at 7.

5. Id. at 9.

6. Sign-on letter to President Obama regarding L-1 visa policy, March 22, 2012, AILA Doc. No. 12032262, accessed March 25, 2012, http://www.aila.org/content/default.aspx?docid=39015; American Immigration Lawyers Association, “Memo to USCIS Director Mayorkas, RE: Interpretation of the Term “Specialized Knowledge” in the Adjudication of L-1B Petitions,” January 24, 2012, AILA Doc. No. 12012560, accessed March 25, 2012, http://www.aila.org/content/default.aspx?bc=8815|38301.

7. DHS OIG L-1 report, supra note 3, at 1.

8. U.S. Department of State, Cable, “Guidance on L Visas and Specialized Knowledge, Reference Document: STATE 002016, 01/11,” January 2011, accessed March 25, 2012, http://travel.state.gov/pdf/Guidance_on_L_Visas_and_Specialized_Knowledge-Jan2011.pdf.

9. See e.g., comments of late Rep. Henry Hyde (R-Ill.): Henry Hyde (R-Ill.). “… Are we being lax in the offshoring of American jobs, often facilitated by ‘in-shore’ training first given to L visa holders right here in the United States, so they can take new skills — and American jobs — home with them?” as reported by Grant Gross in Computerworld, “U.S. lawmakers: L-1 visa program needs changes,” February 5, 2004, accessed March 25, 2012, http://www.computerworld.com/s/article/89884/U.S._lawmakers_L_1_visa_program_needs_changes.

10. See e.g., Rachel Conrad, “Training Your Own Replacement,” Associated Press, February 11, 2009, accessed March 25, 2012, http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2003/08/14/tech/main568324.shtml; David Lazarus, “BofA: Train your own replacement, or no severance pay for you,” SFGate, June 9, 2006, accessed March 25, 2012, http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2006/06/09/BUGPJJA66348.DTL&ao=all.

11. Marco A. Moreno, “L-1 Full Visa Validity Period Change Announced by the U.S. Department of State,” Martindale.com, accessed March 25, 2012, http://www.martindale.com/immigration-law/article_Barnes-Thornburg-LLP_1469212.htm.

12. DHS OIG L-1 report, supra note 3, at 9.

13. Patrick Thibodeau, “Indian, U.S. firms urge Obama action on visas,” Computerworld, March 23, 2012, accessed March 25, 2012, http://www.computerworld.com/s/article/9225521/Indian_U.S._firms_urge_Obama_action_on_visas.

14. USCIS Ombudsman, Annual Report 2011, supra note 1, at 28.

15. National Foundation for American Policy (NFAP), “Analysis: Data Reveal High Denial Rates for L-1 and H-1B Petitions at U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services,” NFAP Policy Brief, February 2012, at 14, accessed March 25, 2012, http://www.nfap.com/pdf/NFAP_Policy_Brief.USCIS_and_Denial_Rates_of_L1_and_H%201B_Petitions.February2012.pdf.

16. Sign-on letter to President Obama regarding L-1 visa policy, supra note 6.

17. USCIS Ombudsman, Annual Report 2011, supra note 1, at 27.

18. NFAP report, supra note 15, at 2.

19. Senate Hearing 111-504, Committee on the Judiciary, United State Senate, May 6, 2009, Serial no. J-111-20, accessed March 25, 2011, http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-111shrg56800/html/CHRG-111shrg56800.htm.

20. DHS OIG L-1 report, supra note 3, at 7.

21. Paul McDougall, “Foreign Tech Pros May Benefit from Visa Changes,” Information Week, March 13, 2012, accessed March 25, 2012, http://www.informationweek.com/news/services/outsourcing/232602532.