Chump change: The Romney–Cotton minimum wage proposal leaves 27 million workers without a pay increase

Those who had high hopes for a serious minimum wage proposal from the Republican Party will be disappointed: The recent proposal released by Sens. Mitt Romney (R-Utah) and Tom Cotton (R-Ark.) would not even increase the minimum wage to 1960s levels, after adjusting for inflation. It is a meager increase that fails to address the problem of low pay in the U.S. economy.

The Romney–Cotton proposal would slowly raise the federal minimum wage from its current level of $7.25 per hour to $10 per hour in 2025. In contrast, the Raise the Wage Act of 2021 would raise the minimum wage to $15 per hour by 2025.

- The Romney–Cotton proposal would leave 27.3 million workers without a pay increase, compared to the Raise the Wage Act.

- Only 4.9 million workers, or 3.2% of the workforce, would receive a pay increase in 2025 under the Romney–Cotton plan, for a total of $3.3 billion dollars in wage increases.

- In contrast, under the Raise the Wage Act, pay would rise for 32.2 million workers, or 21.2% of the workforce, with $108.4 billion in total wage increases.

- 11.2 million fewer Black and Hispanic workers would receive a raise under the Romney–Cotton plan, compared with the Raise the Wage Act.

- 16 million fewer women would see wage increases. Less than one in 20 women (4.1%) would have higher pay under the Romney–Cotton proposal, whereas the Raise the Wage Act would raise earnings for one in every four women (25.8%).

- The average affected worker who works year-round would see their annual pay rise by $700 under the Romney–Cotton plan; under the Raise the Wage Act, the average annual pay increase would be nearly five times that amount ($3,400).

Romney–Cotton’s $10 target by 2025 is the equivalent of $9.19 per hour in today’s dollars, about 13% less than what the minimum wage was at its high-water mark in 1968.

Congress should think big about the Postal Service’s future: Policymakers should focus on rebuilding the Postal Service after the Trump years

This morning, the House Oversight Committee will hold its first hearing on the U.S. Postal Service since Democrats gained control of the presidency and both houses of Congress. Committee members will have the opportunity to question Postmaster General Louis DeJoy, who in his short tenure has severely damaged the Postal Service’s reputation for timely service.

(Related: REPORT The War Against the Postal Service: Postal services should be expanded for the public good, not diminished by special interests.)

DeJoy, a former logistics executive who last year tussled with a federal judge about mail delays, may need to be reminded that he serves the public. USPS board vacancies give President Biden the opportunity to install a Democratic majority on the board this year and potentially oust DeJoy—though this would take some wrangling. The prospect of a newly configured board may make DeJoy more cooperative than he was in the lead-up to the election, when former President Trump planted fears, which mail slowdowns under DeJoy seemed to confirm, that voting by mail was iffy.

In the end, concerns that ballots wouldn’t be delivered in time didn’t materialize. But millions unnecessarily put their health at risk to vote in person during a deadly pandemic. And Trump’s attacks on mail voting emboldened Republicans in their efforts to limit absentee voting to red state seniors and other groups who tend to vote Republican.

Learning during the pandemic: Lessons from the research on education in emergencies for COVID-19 and afterwards

In our recent report, COVID-19 and student performance, equity, and U.S. education policy, we covered the “education in emergencies” research, a body of work that is particularly relevant now to understand the COVID-19 pandemic’s consequences and guide our preparations for its aftermath. This research examines the provision of education in emergency and post-emergency situations caused by pandemics, other natural disasters, and conflicts and wars, often in some of the most troubled countries in the world. Approximately 50 million children are out of school in conflict-affected countries around the world—four times as many as in the 1980s—and we can expect that number to rise due to increased natural disasters and the growing impacts of climate change.

This fascinating research had, until now, gone largely unnoticed to us due to the perceived lack of relevance for guiding domestic education policy in the United States and many of our peer nations. (For those interested, see a recent summary of the research here.) But as we learned when we wrote our report, this research offers four lessons that can help frame the current crisis and plan for the rebuilding of our education system post-pandemic.

First, the research on education in emergencies is extremely clear on the negative consequences of these emergencies on children’s development and learning, not to mention the trauma and stress that some experience in the most serious events. Emergencies, especially the catastrophic ones that this work specializes in, lead to undeniably negative impacts on both educational processes and outcomes. Moreover, the most disadvantaged population subgroups often experience the worst—and longest lasting—consequences.

Unemployment insurance claims rose last week: Congress must act before mid-March, or millions will lose benefits

Another 1.4 million people applied for unemployment insurance (UI) benefits last week, including 861,000 people who applied for regular state UI and 516,000 who applied for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA). The 1.4 million who applied for UI last week was an increase of 187,000 from the prior week, mostly due to an unexpected increase in PUA—the federal program for workers who are not eligible for regular unemployment insurance, like gig workers. The surge in PUA was due entirely to large increase in PUA claims in Ohio, which may be tied to fraudulent filings in the state. The four-week moving average of total initial claims rose by 21,000.

Last week was the 48th straight week total initial claims were greater than the worst week of the Great Recession. (If that comparison is restricted to regular state claims—because we didn’t have PUA in the Great Recession—initial claims last week were still greater than the second-worst week of the Great Recession.)

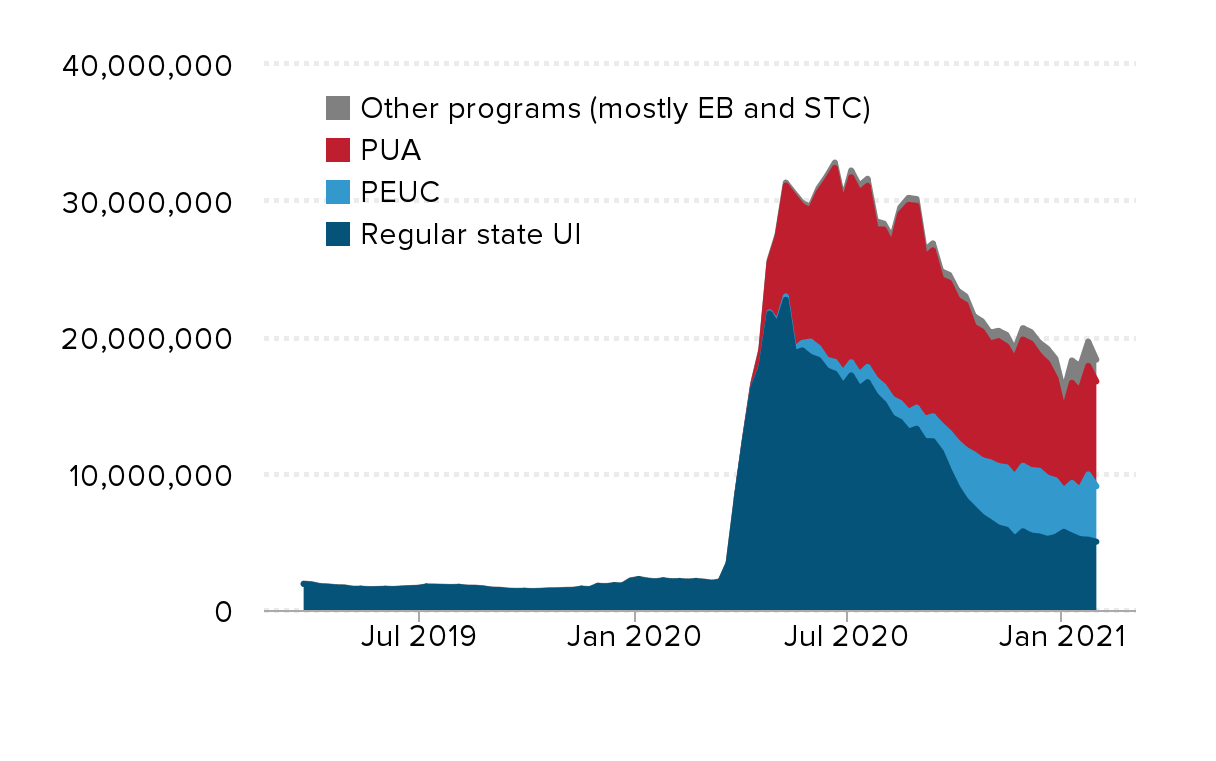

Continuing unemployment claims in all programs, March 23, 2019–January 30, 2021: *Use caution interpreting trends over time because of reporting issues (see below)*

| Date | Regular state UI | PEUC | PUA | Other programs (mostly EB and STC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019-03-23 | 1,905,627 | 31,510 | ||

| 2019-03-30 | 1,858,954 | 31,446 | ||

| 2019-04-06 | 1,727,261 | 30,454 | ||

| 2019-04-13 | 1,700,689 | 30,404 | ||

| 2019-04-20 | 1,645,387 | 28,281 | ||

| 2019-04-27 | 1,630,382 | 29,795 | ||

| 2019-05-04 | 1,536,652 | 27,937 | ||

| 2019-05-11 | 1,540,486 | 28,727 | ||

| 2019-05-18 | 1,506,501 | 27,949 | ||

| 2019-05-25 | 1,519,345 | 26,263 | ||

| 2019-06-01 | 1,535,572 | 26,905 | ||

| 2019-06-08 | 1,520,520 | 25,694 | ||

| 2019-06-15 | 1,556,252 | 26,057 | ||

| 2019-06-22 | 1,586,714 | 25,409 | ||

| 2019-06-29 | 1,608,769 | 23,926 | ||

| 2019-07-06 | 1,700,329 | 25,630 | ||

| 2019-07-13 | 1,694,876 | 27,169 | ||

| 2019-07-20 | 1,676,883 | 30,390 | ||

| 2019-07-27 | 1,662,427 | 28,319 | ||

| 2019-08-03 | 1,676,979 | 27,403 | ||

| 2019-08-10 | 1,616,985 | 27,330 | ||

| 2019-08-17 | 1,613,394 | 26,234 | ||

| 2019-08-24 | 1,564,203 | 27,253 | ||

| 2019-08-31 | 1,473,997 | 25,003 | ||

| 2019-09-07 | 1,462,776 | 25,909 | ||

| 2019-09-14 | 1,397,267 | 26,699 | ||

| 2019-09-21 | 1,380,668 | 26,641 | ||

| 2019-09-28 | 1,390,061 | 25,460 | ||

| 2019-10-05 | 1,366,978 | 26,977 | ||

| 2019-10-12 | 1,384,208 | 27,501 | ||

| 2019-10-19 | 1,416,816 | 28,088 | ||

| 2019-10-26 | 1,420,918 | 28,576 | ||

| 2019-11-02 | 1,447,411 | 29,080 | ||

| 2019-11-09 | 1,457,789 | 30,024 | ||

| 2019-11-16 | 1,541,860 | 31,593 | ||

| 2019-11-23 | 1,505,742 | 29,499 | ||

| 2019-11-30 | 1,752,141 | 30,315 | ||

| 2019-12-07 | 1,725,237 | 32,895 | ||

| 2019-12-14 | 1,796,247 | 31,893 | ||

| 2019-12-21 | 1,773,949 | 29,888 | ||

| 2019-12-28 | 2,143,802 | 32,517 | ||

| 2020-01-04 | 2,245,684 | 32,520 | ||

| 2020-01-11 | 2,137,910 | 33,882 | ||

| 2020-01-18 | 2,075,857 | 32,625 | ||

| 2020-01-25 | 2,148,764 | 35,828 | ||

| 2020-02-01 | 2,084,204 | 33,884 | ||

| 2020-02-08 | 2,095,001 | 35,605 | ||

| 2020-02-15 | 2,057,774 | 34,683 | ||

| 2020-02-22 | 2,101,301 | 35,440 | ||

| 2020-02-29 | 2,054,129 | 33,053 | ||

| 2020-03-07 | 1,973,560 | 32,803 | ||

| 2020-03-14 | 2,071,070 | 34,149 | ||

| 2020-03-21 | 3,410,969 | 36,758 | ||

| 2020-03-28 | 8,158,043 | 0 | 52,494 | 48,963 |

| 2020-04-04 | 12,444,309 | 3,802 | 69,537 | 64,201 |

| 2020-04-11 | 16,249,334 | 31,426 | 216,481 | 89,915 |

| 2020-04-18 | 17,756,054 | 63,720 | 1,172,238 | 116,162 |

| 2020-04-25 | 21,723,230 | 91,724 | 3,629,986 | 158,031 |

| 2020-05-02 | 20,823,294 | 173,760 | 6,361,532 | 175,289 |

| 2020-05-09 | 22,725,217 | 252,257 | 8,120,137 | 216,576 |

| 2020-05-16 | 18,791,926 | 252,952 | 11,281,930 | 226,164 |

| 2020-05-23 | 19,022,578 | 546,065 | 10,010,509 | 247,595 |

| 2020-05-30 | 18,548,442 | 1,121,306 | 9,597,884 | 259,499 |

| 2020-06-06 | 18,330,293 | 885,802 | 11,359,389 | 325,282 |

| 2020-06-13 | 17,552,371 | 783,999 | 13,093,382 | 336,537 |

| 2020-06-20 | 17,316,689 | 867,675 | 14,203,555 | 392,042 |

| 2020-06-27 | 16,410,059 | 956,849 | 12,308,450 | 373,841 |

| 2020-07-04 | 17,188,908 | 964,744 | 13,549,797 | 495,296 |

| 2020-07-11 | 16,221,070 | 1,016,882 | 13,326,206 | 513,141 |

| 2020-07-18 | 16,691,210 | 1,122,677 | 13,259,954 | 518,584 |

| 2020-07-25 | 15,700,971 | 1,193,198 | 10,984,864 | 609,328 |

| 2020-08-01 | 15,112,240 | 1,262,021 | 11,504,089 | 433,416 |

| 2020-08-08 | 14,098,536 | 1,376,738 | 11,221,790 | 549,603 |

| 2020-08-15 | 13,792,016 | 1,381,317 | 13,841,939 | 469,028 |

| 2020-08-22 | 13,067,660 | 1,434,638 | 15,164,498 | 523,430 |

| 2020-08-29 | 13,283,721 | 1,547,611 | 14,786,785 | 490,514 |

| 2020-09-05 | 12,373,201 | 1,630,711 | 11,808,368 | 529,220 |

| 2020-09-12 | 12,363,489 | 1,832,754 | 12,153,925 | 510,610 |

| 2020-09-19 | 11,561,158 | 1,989,499 | 10,686,922 | 589,652 |

| 2020-09-26 | 10,172,332 | 2,824,685 | 10,978,217 | 579,582 |

| 2020-10-03 | 8,952,580 | 3,334,878 | 10,450,384 | 668,691 |

| 2020-10-10 | 8,038,175 | 3,711,089 | 10,622,725 | 615,066 |

| 2020-10-17 | 7,436,321 | 3,983,613 | 9,332,610 | 778,746 |

| 2020-10-24 | 6,837,941 | 4,143,389 | 9,433,127 | 746,403 |

| 2020-10-31 | 6,452,002 | 4,376,847 | 8,681,647 | 806,430 |

| 2020-11-07 | 6,037,690 | 4,509,284 | 9,147,753 | 757,496 |

| 2020-11-14 | 5,890,220 | 4,569,016 | 8,869,502 | 834,740 |

| 2020-11-21 | 5,213,781 | 4,532,876 | 8,555,763 | 741,078 |

| 2020-11-28 | 5,766,130 | 4,801,408 | 9,244,556 | 834,685 |

| 2020-12-05 | 5,457,941 | 4,793,230 | 9,271,112 | 841,463 |

| 2020-12-12 | 5,393,839 | 4,810,334 | 8,453,940 | 937,972 |

| 2020-12-19 | 5,205,841 | 4,491,413 | 8,383,387 | 1,070,810 |

| 2020-12-26 | 5,347,440 | 4,166,261 | 7,442,888 | 1,450,438 |

| 2021-01-02 | 5,727,359 | 3,026,952 | 5,707,397 | 1,526,887 |

| 2021-01-09 | 5,446,993 | 3,863,008 | 7,334,682 | 1,638,247 |

| 2021-01-16 | 5,188,211 | 3,604,894 | 7,218,801 | 1,826,573 |

| 2021-01-23 | 5,156,985 | 4,779,341 | 7,943,448 | 1,785,954 |

| 2021-01-30 | 5,003,107 | 4,061,305 | 7,685,389 | 1,590,360 |

Data are not seasonally adjusted. A full list of programs can be found in the bottom panel of the table on page 4 at this link: https://www.dol.gov/ui/data.pdf.

Source: U.S. Employment and Training Administration, Initial Claims [ICSA], retrieved from Department of Labor (DOL), https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/docs/persons.xls and https://www.dol.gov/ui/data.pdf, February 18, 2021.

Figure A shows continuing claims in all programs over time (the latest data for this are for January 30th). Continuing claims are currently more than 16 million above where they were a year ago. Further, there are 25.5 million workers—15.0% of the workforce—who were either unemployed, otherwise out of work because of COVID-19, or had seen a drop in hours and pay because of the pandemic.

The December 11-week extensions of PEUC and PUA just kick the can down the road—they are not long enough. Congress must pass further extensions well before mid-March, or millions will exhaust benefits at that time, when the virus is still rampant and the labor market is still weak. Roughly $2 trillion in relief and recovery is crucial to keep millions of families afloat.

There are 18 million more continuing UI claims than one year ago: Congress must pass relief package

Another 1.1 million people applied for unemployment insurance (UI) benefits last week, including 793,000 people who applied for regular state UI and 335,000 who applied for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA). The 1.1 million who applied for UI last week was roughly unchanged from the prior week (down 53,000). The four-week moving average of total claims was also flat (down 15,000). Total initial claims are roughly where they were in mid-October.

Last week was the 47th straight week total initial claims were greater than the worst week of the Great Recession. (If that comparison is restricted to regular state claims—because we didn’t have PUA in the Great Recession—initial claims last week were still greater than the third-worst week of the Great Recession.)

U.S. trade deficit hits record high in 2020: The Biden administration must prioritize rebuilding domestic manufacturing

The U.S. Census Bureau reported recently that the U.S. goods trade deficit reached a record of $915.8 billion in 2020, an increase of $51.5 billion (6.0%). The broader goods and services deficit reached $678.7 billion in 2020, an increase of $101.9 billion (17.7%). The U.S. goods trade deficit in 2020 was the largest on record, and the goods and services deficit was the largest since 2008.

The rapid growth of U.S. trade deficits reflects the combined effects of the COVID-19 crisis, which caused U.S. exports to fall by more ($217.7 billion) than imports ($166.2 billion), and by the persistent failure of U.S. trade and exchange rate policies over the past two decades. The single most important cause of large and growing trade deficits is persistent overvaluation of the U.S. dollar, which makes imports artificially cheap and U.S. exports less competitive.

The U.S. goods trade deficit is increasingly dominated by trade in manufactured products, as shown in the figure below. The manufacturing trade deficit reached record highs of $897.7 billion—98% of the total U.S. goods trade deficit—and 4.3% of U.S. GDP in 2020. Primarily due to these rapidly growing manufacturing trade deficits, the U.S. lost nearly 5 million manufacturing jobs and 91,000 manufacturing plants between 1997 and 2018 alone, and an additional 582,000 manufacturing jobs in 2020.

A stalled recovery: Hires fall in the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey

Last week, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported that, as of the middle of January, the economy was still 9.9 million jobs below where it was in February 2020. This translates into a 12.1 million job shortfall when using a reasonable counterfactual of job growth if the recession hadn’t occurred. Today’s BLS Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) reports little change in December, a clear sign that the recovery is not charging ahead. In fact, hiring and job openings are below where they were before the recession hit, which makes it impossible to recover anytime soon when we have such a massive hole to fill in the labor market.

In December, job openings were little changed while hires softened considerably, falling from 5.9 million to 5.5 million. In particular, hiring decreased in leisure and hospitality—in both accommodation and food services and in arts, entertainment, and recreation. Hiring also declined in transportation, warehousing, and utilities.

One of the most striking indicators from today’s report is the job seekers ratio—the ratio of unemployed workers (averaged for mid-December and mid-January) to job openings (at the end of December). On average, there were 10.4 million unemployed workers compared with only 6.6 million job openings. This translates into a job seekers ratio of about 1.6 unemployed workers to every job opening. Put another way, for every 16 workers who were officially counted as unemployed, there were only available jobs for 10 of them. That means, no matter what they did, there were no jobs for 3.8 million unemployed workers. And this misses the fact that many more weren’t counted among the unemployed: The economic pain remains widespread with 25.5 million workers hurt by the coronavirus downturn.

On the whole, the U.S. economy is seeing a significantly slower hiring pace than we experienced in May or June. In December, hiring was below where it was before the recession, a big problem given that we have only recovered just over half of the job losses from this spring. And job openings are now substantially below where they were before the recession began (6.6 million at the end of December, compared to 7.1 million on average in the year prior to the recession). With hiring and job openings at these levels, the economy is facing a long, slow recovery without additional action from Congress.

Policymakers need to act now at the scale of the problem to address the continuing economic crisis.

CBO analysis confirms that a $15 minimum wage raises earnings of low-wage workers, reduces inequality, and has significant and direct fiscal effects: Large progressive redistribution of income caused by higher minimum wage leads to significant and cross-cutting fiscal effects

This post has been revised slightly as of February 12. Specifically, it refers only to a literature review by Dube (2019) on the employment effects of the minimum wage on the low-wage workforce. It also does not specifically quantify the influence that employment effect assumptions have on the Congressional Budget Office’s estimated budgetary effects, since it is not possible to do that without additional information that is not published in CBO’s report.

Today’s analysis from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) highlights a number of things that policymakers should keep in mind as they consider minimum wage legislation in the upcoming Congress. First, the benefits of passing a significant increase in the federal minimum wage—like the Raise the Wage Act of 2021—are enormous. Today’s CBO analysis indicates that raising the federal minimum wage to $15 by 2025 would benefit 27 million workers and would lead to a 10-year increase in wages of $333 billion for the low-wage workforce—the same workforce that has borne the brunt of the COVID-19 economic shock and worked in essential jobs that have kept the economy going. In short, given which parts of the workforce have economically suffered the most from the pandemic, it seems more than appropriate to include a minimum wage increase in any relief and rescue package. Second, the federal minimum wage is a powerful policy instrument to redistribute income and bargaining power towards low-wage workers, and as a result it has very large gross fiscal effects on both federal revenue and federal spending.

In our analysis released last week, we highlighted a number of large gross changes to both spending and revenue that were likely to result from the large increase in earnings for low-wage workers if the minimum wage was significantly increased.1 In particular, we estimated that by raising earnings of low-wage workers, a $15 minimum wage by 2025 would significantly reduce spending on Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and the Earned Income and Child Tax Credits.2 CBO’s analysis today also estimates outlays would fall for these public assistance programs, as they predict the higher minimum wage would lift nearly 1 million people out of poverty.

CBO also estimates gross changes on the spending and the tax side of the federal budget from both the earnings increase of low-wage workers and assumptions regarding how this earnings increase is “financed.” They find large gross changes that net out to a small increase in budget deficits. These differences in emphasis and bottom-line numbers between independent analyses like ours and the CBO numbers today should not distract from the agreed-upon finding by all analyses of this issue: The effects of a significant increase in the federal minimum wage on the federal budget are large.

The Biden rescue plan is neither risky nor a distraction from structural issues

Economist Larry Summers raised fears today that the Biden administration’s economic rescue plan might go too far, leading to economic overheating or squandering political and economic space for long-run reforms down the road. Neither of these fears are very compelling.

On the first–the danger of economic overheating–there’s not much more to add to what I and several others have already said on this: The U.S. economy has run far too-cool for decades, and this has stunted growth and deprived millions of potential job opportunities and tens of millions of potential opportunities for faster pay raises. Frequently, those worried about overheating cite current estimates from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) of the “output gap”—the gap between income generated in today’s economy and what could be generated (or potential output) if there was no downward pressure on spending by households, businesses, and governments (aggregate demand). These current CBO estimates look relatively small compared to the Biden rescue plan’s fiscal support. But, these current estimates are almost certainly too-small. To provide just one piece of evidence—these estimates suggest that the economy was running above potential output in 2019 before COVID-19struck. But there was no evidence of overheating that year—price inflation was tame and wage growth actually decelerated.

If the vaccines take hold and there is a significant relaxation of social distancing measures in the coming year, the economic relief we’ve provided so far through this crisis and the Biden plan could combine to see the economy spring to life and generate a recovery far faster than what we’ve seen in the past few recessions. If this happens, and if the unemployment rate falls far beneath what it was in the pre-COVID period and stays below this for a few years, this will be an affirmatively good thing, not something to fear.Read more

The economy Trump handed off to President Biden: 25.5 million workers—15.0% of the workforce—hit by the coronavirus crisis in January

The official unemployment rate was 6.3% in January—matching the maximum unemployment rate of the early 2000s downturn—and the official number of unemployed workers was 10.1 million, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). However, these official numbers are a vast undercount of the number of workers being harmed by the weak labor market. In fact, 25.5 million workers—15.0% of the workforce—are either unemployed, otherwise out of work due to the pandemic, or employed but experiencing a drop in hours and pay.

Here are the missing factors: