Does the budget deal include benefit cuts?

Many of us reacted to the tentative budget deal with surprised relief. Assuming the agreement holds, the White House was able to lift the debt ceiling and end the sequester without losing limbs in the process, as my colleague Ross Eisenbrey aptly put it. This time the administration resisted the urge to throw red meat to the other side’s lions.

Inevitably, the deal will intensify dissent on the right. But there is also a surprisingly heated debate about the seemingly benign Social Security provisions among advocates, some of whom view any cost savings as benefit cuts and say an off-budget program with a dedicated funding stream should not be discussed in budget negotiations (though they don’t object to including transfers to the disability program in this budget deal). In particular, a vocal minority opposes a provision that would no longer allow people to take advantage of the “file and suspend” strategy, whereby someone eligible for both retirement and spousal benefits delays take-up of the former to receive a larger benefit at age 70, while receiving the latter in the interim (most people without clever financial advisers simply receive the higher of the two benefits whenever they apply).

Eliminating “aggressive Social Security-claiming strategies, which allow upper-income beneficiaries to manipulate the timing of collection of Social Security benefits in order to maximize delayed retirement credits” was something the president included in his fiscal-year 2015 budget, not something the administration reluctantly agreed to. And most advocates, http://www.canadianpharmacy365.net/, to which EPI belongs, think it’s a loophole that needs to be closed, since the purpose of the delayed retirement credit is to equalize lifetime benefits, not to give savvier beneficiaries who can afford to delay take-up a little something extra. The dissidents counter that a benefit cut by any other name is still a benefit cut, and say it’s a strategy that can help divorced women, who can be particularly vulnerable in retirement.

The dissidents make a strong case with feminist appeal. But it’s still double dipping even if a few people who take advantage actually need a larger benefit. In the end, it all seems a distraction from the benefits of the agreement, which include averting large benefit cuts to disabled beneficiaries.

The Republican Study Committee wants to ratchet austerity up well past the sequester

A bit over four years ago, the U.S. economy threatened to breach the legislated (and totally arbitrary) national debt ceiling. There was no economic sign (high interest rates, for example) that argued that public debt was too high, and there were many economic signs that such debt was actually too low. Yet because of a quirk in American economic policy, Congress must periodically act to raise the nominal value of the debt allowed to be issue by the federal government. This is normally a pro forma vote, at least after members of Congress are allowed to rail against what they see as the fiscal policy failings of the current president.

But in August 2011, in an unprecedented breach of Congressional norms, Republicans in Congress instead used the looming breach of the debt ceiling to demand spending cuts. Besides breaching legislative norms, the resulting cuts were also economically disastrous. The Budget Control Act (BCA) of 2011 and the resulting spending austerity (often short-handed not quite accurately as “the sequester”) fully explains why the U.S. economy has yet to reach a full recovery from the Great Recession, even more than six years after the recession officially ended. If we had instead simply followed the average path of federal spending that characterized all previous post-World War II recessions, the U.S. economy would be at full employment by now, and the Fed would have certainly begun raising interest rates a long time ago.

The fiscal drag resulting from the sequester relented a little in the past two years, as the result of a compromise reached between the House and Senate budget committees. But this compromise only rolled back sequester cuts for two years. For fiscal year 2016, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that not extending this compromise and instead returning to 2011 BCA spending targets could cost as many as 800,000 jobs as these cuts drag on aggregate demand.

Pennsylvania’s upcoming budget decision highlights the choice facing states across the country

Over the past few years, many states have faced critical choices about whether to raise state revenues, hold firm to existing—potentially inadequate—tax structures, or cut taxes, sometimes on top of cuts made in earlier years. Today, lawmakers in Pennsylvania are again considering these same choices, but with a somewhat unique opportunity to change course from the path they took earlier in the recovery. Two weeks ago, Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf released a plan to raise revenue which, he stressed in a press conference, will begin to address the state’s structural budget deficit and reverse deep cuts to education spending that occurred in 2010-11.

As lawmakers throughout the country consider plans for the coming fiscal year, it is instructive to compare the fiscal and economic performance of Pennsylvania in recent years with other states that made either similar or starkly different fiscal choices. For example, California and Minnesota raised taxes to improve their fiscal health and to reinvest in education, while Kansas and Wisconsin followed the same path as Pennsylvania—reducing taxes by varying degrees and dramatically cutting education spending.

The results of this policy experiment can be summarized as follows:

- The two states that raised revenues have enjoyed percent job growth since 2010-11 that is one-and-a-half to three times larger than the three states that cut taxes.

- The states that increased taxes have seen revenue growth—both as a result of the tax changes and as a result of stronger recoveries—of 8 percent and 15 percent. Kansas has seen its revenues fall 5 percent and Pennsylvania and Wisconsin have seen revenue growth of 5 percent and 7 percent, meager enough to make fiscal stability and reinvestment in vital programs difficult.

- State school funding per pupil has increased 15-21 percent in Minnesota and California while plunging 9-14 percent in the three tax-cut states. That means the ratio of funding per pupil in Minnesota and California compared to any of the other three states has shifted 26-41 percent in just four years.

More of the same: JOLTS is continued evidence of a slow moving economy

Today’s Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) report shows there has been little change in the labor market for America’s workers. The rate of job openings actually decreased in August to 5.4 million. At the same time, the hires rate held steady while the quits rate remains depressed. Coupled with jobs reports so far this year, today’s report provides more evidence of a slow moving economy, with meager wage growth and employment growth that’s just keeping up with the growth in the working age population.

There is still a significant gap between the number of people looking for jobs and the number of job openings. The figure below shows the levels of unemployed workers and job openings. You can see the labor market improve over the last five years, as the number of unemployed workers falls and job openings rise. In a stronger economy (like the one shown in the initial year of data), these levels would be much closer together. Today, there are still 1.5 active job seekers for every job opening. Furthermore, on top of the 8+ million unemployed workers warming the bench, there are still four million workers sitting in the stands with little hope to even get in the game.

Job openings levels and unemployment levels, 2000-2015

| Month | Job Openings level | Unemployment level |

|---|---|---|

| Dec-2000 | 4.934 | 5.634 |

| Jan-2001 | 5.273 | 6.023 |

| Feb-2001 | 4.706 | 6.089 |

| Mar-2001 | 4.618 | 6.141 |

| Apr-2001 | 4.668 | 6.271 |

| May-2001 | 4.444 | 6.226 |

| Jun-2001 | 4.232 | 6.484 |

| Jul-2001 | 4.354 | 6.583 |

| Aug-2001 | 4.095 | 7.042 |

| Sep-2001 | 3.973 | 7.142 |

| Oct-2001 | 3.594 | 7.694 |

| Nov-2001 | 3.545 | 8.003 |

| Dec-2001 | 3.586 | 8.258 |

| Jan-2002 | 3.587 | 8.182 |

| Feb-2002 | 3.412 | 8.215 |

| Mar-2002 | 3.605 | 8.304 |

| Apr-2002 | 3.357 | 8.599 |

| May-2002 | 3.525 | 8.399 |

| Jun-2002 | 3.325 | 8.393 |

| Jul-2002 | 3.343 | 8.39 |

| Aug-2002 | 3.462 | 8.304 |

| Sep-2002 | 3.319 | 8.251 |

| Oct-2002 | 3.502 | 8.307 |

| Nov-2002 | 3.585 | 8.52 |

| Dec-2002 | 3.074 | 8.64 |

| Jan-2003 | 3.686 | 8.52 |

| Feb-2003 | 3.402 | 8.618 |

| Mar-2003 | 3.101 | 8.588 |

| Apr-2003 | 3.182 | 8.842 |

| May-2003 | 3.201 | 8.957 |

| Jun-2003 | 3.356 | 9.266 |

| Jul-2003 | 3.195 | 9.011 |

| Aug-2003 | 3.239 | 8.896 |

| Sep-2003 | 3.054 | 8.921 |

| Oct-2003 | 3.196 | 8.732 |

| Nov-2003 | 3.316 | 8.576 |

| Dec-2003 | 3.334 | 8.317 |

| Jan-2004 | 3.391 | 8.37 |

| Feb-2004 | 3.437 | 8.167 |

| Mar-2004 | 3.42 | 8.491 |

| Apr-2004 | 3.466 | 8.17 |

| May-2004 | 3.658 | 8.212 |

| Jun-2004 | 3.384 | 8.286 |

| Jul-2004 | 3.835 | 8.136 |

| Aug-2004 | 3.578 | 7.99 |

| Sep-2004 | 3.704 | 7.927 |

| Oct-2004 | 3.779 | 8.061 |

| Nov-2004 | 3.456 | 7.932 |

| Dec-2004 | 3.846 | 7.934 |

| Jan-2005 | 3.595 | 7.784 |

| Feb-2005 | 3.842 | 7.98 |

| Mar-2005 | 3.891 | 7.737 |

| Apr-2005 | 4.115 | 7.672 |

| May-2005 | 3.824 | 7.651 |

| Jun-2005 | 4.018 | 7.524 |

| Jul-2005 | 4.162 | 7.406 |

| Aug-2005 | 4.085 | 7.345 |

| Sep-2005 | 4.227 | 7.553 |

| Oct-2005 | 4.23 | 7.453 |

| Nov-2005 | 4.341 | 7.566 |

| Dec-2005 | 4.249 | 7.279 |

| Jan-2006 | 4.278 | 7.064 |

| Feb-2006 | 4.308 | 7.184 |

| Mar-2006 | 4.537 | 7.072 |

| Apr-2006 | 4.495 | 7.12 |

| May-2006 | 4.432 | 6.98 |

| Jun-2006 | 4.331 | 7.001 |

| Jul-2006 | 4.081 | 7.175 |

| Aug-2006 | 4.411 | 7.091 |

| Sep-2006 | 4.498 | 6.847 |

| Oct-2006 | 4.454 | 6.727 |

| Nov-2006 | 4.622 | 6.872 |

| Dec-2006 | 4.552 | 6.762 |

| Jan-2007 | 4.59 | 7.116 |

| Feb-2007 | 4.481 | 6.927 |

| Mar-2007 | 4.657 | 6.731 |

| Apr-2007 | 4.534 | 6.85 |

| May-2007 | 4.531 | 6.766 |

| Jun-2007 | 4.639 | 6.979 |

| Jul-2007 | 4.43 | 7.149 |

| Aug-2007 | 4.508 | 7.067 |

| Sep-2007 | 4.481 | 7.17 |

| Oct-2007 | 4.278 | 7.237 |

| Nov-2007 | 4.278 | 7.24 |

| Dec-2007 | 4.323 | 7.645 |

| Jan-2008 | 4.223 | 7.685 |

| Feb-2008 | 4.039 | 7.497 |

| Mar-2008 | 4.012 | 7.822 |

| Apr-2008 | 3.85 | 7.637 |

| May-2008 | 4 | 8.395 |

| Jun-2008 | 3.67 | 8.575 |

| Jul-2008 | 3.762 | 8.937 |

| Aug-2008 | 3.584 | 9.438 |

| Sep-2008 | 3.21 | 9.494 |

| Oct-2008 | 3.273 | 10.074 |

| Nov-2008 | 3.059 | 10.538 |

| Dec-2008 | 3.049 | 11.286 |

| Jan-2009 | 2.763 | 12.058 |

| Feb-2009 | 2.794 | 12.898 |

| Mar-2009 | 2.493 | 13.426 |

| Apr-2009 | 2.271 | 13.853 |

| May-2009 | 2.413 | 14.499 |

| Jun-2009 | 2.388 | 14.707 |

| Jul-2009 | 2.146 | 14.601 |

| Aug-2009 | 2.294 | 14.814 |

| Sep-2009 | 2.434 | 15.009 |

| Oct-2009 | 2.376 | 15.352 |

| Nov-2009 | 2.419 | 15.219 |

| Dec-2009 | 2.49 | 15.098 |

| Jan-2010 | 2.706 | 15.046 |

| Feb-2010 | 2.561 | 15.113 |

| Mar-2010 | 2.652 | 15.202 |

| Apr-2010 | 3.097 | 15.325 |

| May-2010 | 2.9 | 14.849 |

| Jun-2010 | 2.728 | 14.474 |

| Jul-2010 | 2.929 | 14.512 |

| Aug-2010 | 2.869 | 14.648 |

| Sep-2010 | 2.782 | 14.579 |

| Oct-2010 | 3.026 | 14.516 |

| Nov-2010 | 3.072 | 15.081 |

| Dec-2010 | 2.909 | 14.348 |

| Jan-2011 | 2.917 | 14.046 |

| Feb-2011 | 3.065 | 13.828 |

| Mar-2011 | 3.132 | 13.728 |

| Apr-2011 | 3.099 | 13.956 |

| May-2011 | 3.032 | 13.853 |

| Jun-2011 | 3.194 | 13.958 |

| Jul-2011 | 3.417 | 13.756 |

| Aug-2011 | 3.138 | 13.806 |

| Sep-2011 | 3.557 | 13.929 |

| Oct-2011 | 3.422 | 13.599 |

| Nov-2011 | 3.215 | 13.309 |

| Dec-2011 | 3.527 | 13.071 |

| Jan-2012 | 3.653 | 12.812 |

| Feb-2012 | 3.517 | 12.828 |

| Mar-2012 | 3.837 | 12.696 |

| Apr-2012 | 3.627 | 12.636 |

| May-2012 | 3.696 | 12.668 |

| Jun-2012 | 3.785 | 12.688 |

| Jul-2012 | 3.587 | 12.657 |

| Aug-2012 | 3.637 | 12.449 |

| Sep-2012 | 3.614 | 12.106 |

| Oct-2012 | 3.729 | 12.141 |

| Nov-2012 | 3.741 | 12.026 |

| Dec-2012 | 3.64 | 12.272 |

| Jan-2013 | 3.77 | 12.497 |

| Feb-2013 | 4.023 | 11.967 |

| Mar-2013 | 3.891 | 11.653 |

| Apr-2013 | 3.84 | 11.735 |

| May-2013 | 3.829 | 11.671 |

| Jun-2013 | 3.864 | 11.736 |

| Jul-2013 | 3.829 | 11.357 |

| Aug-2013 | 3.893 | 11.241 |

| Sep-2013 | 3.955 | 11.251 |

| Oct-2013 | 4.076 | 11.161 |

| Nov-2013 | 4.073 | 10.814 |

| Dec-2013 | 3.977 | 10.376 |

| Jan-2014 | 3.906 | 10.28 |

| Feb-2014 | 4.160 | 10.387 |

| Mar-2014 | 4.210 | 10.384 |

| Apr-2014 | 4.417 | 9.696 |

| May-2014 | 4.608 | 9.761 |

| Jun-2014 | 4.710 | 9.453 |

| Jul-2014 | 4.726 | 9.648 |

| Aug-2014 | 4.925 | 9.568 |

| Sep-2014 | 4.678 | 9.237 |

| Oct-2014 | 4.849 | 8.983 |

| Nov-2014 | 4.886 | 9.071 |

| Dec-2014 | 4.877 | 8.688 |

| Jan-2015 | 4.965 | 8.979 |

| Feb-2015 | 5.144 | 8.705 |

| Mar-2015 | 5.109 | 8.575 |

| Apr-2015 | 5.334 | 8.549 |

| May-2015 | 5.357 | 8.674 |

| Jun-2015 | 5.323 | 8.299 |

| Jul-2015 | 5.668 | 8.266 |

| Aug-2015 | 5.370 | 8.029 |

Note: Shaded areas denote recessions.

Source: EPI analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey and Current Population Survey

Urban Outfitters gets into the holiday spirit by asking its employees to work for free

An internal memo to the staff of hipster retailer Urban Outfitters, which was leaked to Gawker, gives us a window into how the retailer’s Philadelphia-based parent company, URBN, plans to deal with the upcoming holiday rush. Their not-so-innovative idea: ask employees to work for free.

In a “call for volunteers,” URBN informs the staff that “October will be the busiest month yet for the [fulfillment] center, and we need additional helping hands to ensure the timely shipment of orders.” It goes on to explain to its employees that “as a volunteer, you will work side by side with your [fulfillment center] colleagues to help pick, pack and ship orders for our wholesale and direct customers.”

In short, URBN, whose executive staff took home a combined $12.2 million in compensation last year, is asking its employees to take time out of their weekends to commute to rural Pennsylvania and work in a warehouse—for free.

Unsurprisingly, this request is most likely illegal. According to the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), it is unlawful for a for-profit employer “to suffer or permit” someone to work without compensation—consequently, asking an employee who is not “exempt” to “volunteer” for a for-profit enterprise, whether they are salaried or hourly, is explicitly prohibited by the FLSA.

Failure to stem dollar appreciation has put manufacturing recovery in reverse

This week, President Obama announced the completion of negotiations on the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The TPP, which is likely to drive down middle-class wages and increase offshoring and job loss, has been widely criticized by leading members of Congress from both parties. Hillary Clinton, Bernie Saunders, and other presidential candidates have announced their opposition to the deal.

Meanwhile, U.S. jobs and the recovery are threatened by a growing trade deficit in manufactured products, which is on pace to reach $633.9 billion in 2015, as shown in Figure A, below. This deficit exceeds the previous peak of $558.5 billion in 2006 (not shown) by more than $75 billion. The increase in the manufacturing trade deficit in 2015 alone will amount to 0.5 percent of projected GDP, and will likely reduced projected growth by even more as manufacturing wages and profits are reduced.

U.S. manufacturing trade deficit, 2007–2015* (billions of dollars)

| Year | U.S. manufacturing trade deficit (billions of dollars) |

|---|---|

| 2007 | 532.222 |

| 2008 | 456.240 |

| 2009 | 319.471 |

| 2010 | 412.740 |

| 2011 | 440.602 |

| 2012 | 458.692 |

| 2013 | 449.276 |

| 2014 | 515.131 |

| 2015 | 633.915 |

* Estimated, based on year-to-date trade data through August 2015

Source: Author's analysis of U.S. International Trade Commission Trade DataWeb

The growth of the manufacturing trade deficit is starting to have an impact on manufacturing employment, which has lost 27,300 jobs since July 2015, as shown in Figure B, below. Growing exports support U.S. jobs, but increases in imports cost jobs, so even if overall exports are growing, trade deficits hurt U.S. employment—especially in manufacturing, because most traded goods are manufactured products. Although the United States had regained more than 800,000 manufacturing jobs since 2010, the low point of the manufacturing collapse after the great recession, overall manufacturing employment is still 1.4 million jobs lower than it was in December 2007.

ACA excise tax on expensive health plans is an unambiguous pay cut

The Affordable Care Act is making the U.S. health system much more efficient and fair. One provision of it, however, remains controversial, even among those strongly supportive of the overall law. This is the 40 percent excise tax on the marginal cost of expensive health plans, sometimes very misleadingly referred to as the “Cadillac Tax.” Defenders of this tax, and even many reporters, have claimed recently that the tax will “give Americans a raise” or will “raise incomes.” These claims are wrong. Instead, the excise tax— even in the best case—is an unambiguous cut in after-tax pay for workers.

Beginning in 2018, the tax will be levied on the cost of single plans in excess of $10,200 a year, and non-single plans in excess of $27,500. The point of the tax is to nudge workers into taking thinner health plans—those with lower premiums that stay under the threshold for the tax. But choosing plans with lower premiums will generally lead to higher out-of-pocket costs – higher deductibles, co-pays and/or other forms of cost sharing. This increased cost-sharing is the point of the tax, not a byproduct. By boosting the marginal cost of each new episode of obtaining health care, the theory is that health consumers will shop more wisely and cut back on unnecessary care. We have strong reservations about leaning on this dynamic as effective cost containment, but for now I’ll focus on a side claim made by defenders: that a happy consequence of accepting plans with lower premium costs is that workers will see higher wages.

The theory for this is that if employers cut back on contributions to health insurance premiums as workers choose thinner plans, more money will become available to boost non-health care compensation—wages or other fringe benefits. This presumed increase in wages actually accounts for a significant share of estimated revenue that will be raised by the tax. (I should note that if the compensating wage boost stemming from lower employer premium payments does not happen, this does not necessarily mean that the tax won’t raise money. Lower premium costs and unchanged wages paid by employers imply a rise in business income or profitability, and this higher profitability should mean higher tax payments by employers.)

Human resources group shoots at Obama overtime rule but misses

This will be the first in a series of blog posts examining some of the comments submitted to the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) in response to its notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) on overtime pay for salaried employees. Approximately 300,000 comments have been acknowledged by DOL; I want to call attention to a few of the most salient comments, both pro and con.

I’ll start with the Human Resources Policy Association (HRPA), which claims to represent “the most senior human resource executives in more than 360 of the largest companies in the United States.” HRPA’s comment addresses both what DOL actually proposed as well as ideas it was merely considering. Three of HRPA’s criticisms are worth considering, though each is deeply flawed:

- The proposed salary level is too high because it “would effectively nullify the statutory exemption for a significant number of employees Congress meant to exempt.”

- The proposed rule would limit “workplace flexibility.”

- The rule should not index the salary level test.

The salary level proposed by DOL is modest and meets the congressional intent

HRPA’s argument that the salary level is too high begins with a misstatement of the role of the salary level test. It very clearly is not intended to set a “level at which the employees below it clearly would not meet any [executive, administrative, or professional (EAP)] duties test.” The salary level test would be redundant if the employees covered by it clearly would not meet any EAP duties test. In fact, DOL has long expressed the exact opposite intent. In the words of DOL’s 1949 report and recommendations, “the salary level must be high enough to include only those persons about whose exemption there is normally no question” (Weiss, 23).

Tax on expensive health insurance plans could cut care along with costs

This piece originally appeared in the Wall Street Journal’s Think Tank.

The Affordable Care Act took enormous strides toward providing access to health-care coverage to the tens of millions of uninsured Americans and reining in the skyrocketing costs of health care that heavily pressured households and public budgets, addressing what we consider the most glaring shortcomings of the U.S. health system. When it comes to cost control, however, the policy virtue of one provision of the ACA–the excise tax on high-cost employer-sponsored health insurance plans, frequently called the Cadillac tax–is often overstated.

This provision levies a 40% tax on the cost of insurance plans that exceed $10,200 for individuals in 2018 ($27,500 for non-single plans). The policy goal of this tax is to nudge workers into opting for plans that charge lower premiums. Lower premiums in turn imply higher co-pays, deductibles, and cost-sharing. To be clear, these higher out-of-pocket costs are the point of the tax, not a byproduct. The theory is that as each new episode of obtaining care becomes more expensive households will cut back on health spending and this will help contain costs.

We think this is roughly true. Evidence shows that making health care more expensive does induce people to consume less of it. But the same evidence shows that people do not cut back only on care that is ineffective or somehow luxurious; instead, they cut back across the board. Expecting sick Americans to decide on the fly in an opaque and uncompetitive marketplace what health care is cost-effective–and what is not–is an unrealistic and unfair approach to containing costs.

While overall costs may be pushed down by the excise tax, this is a good outcome only if one believes that the health care squeezed out is merely the ineffective kind. But a lot of welfare-improving care may also be a casualty, and for some patients, cutting back on medically indicated care because of the increased cost-sharing could increase their overall spending. For example: some patients who cut back on low-cost pills to contain cholesterol end up in emergency rooms.

Disappointing Jobs Numbers and Not Enough Teachers

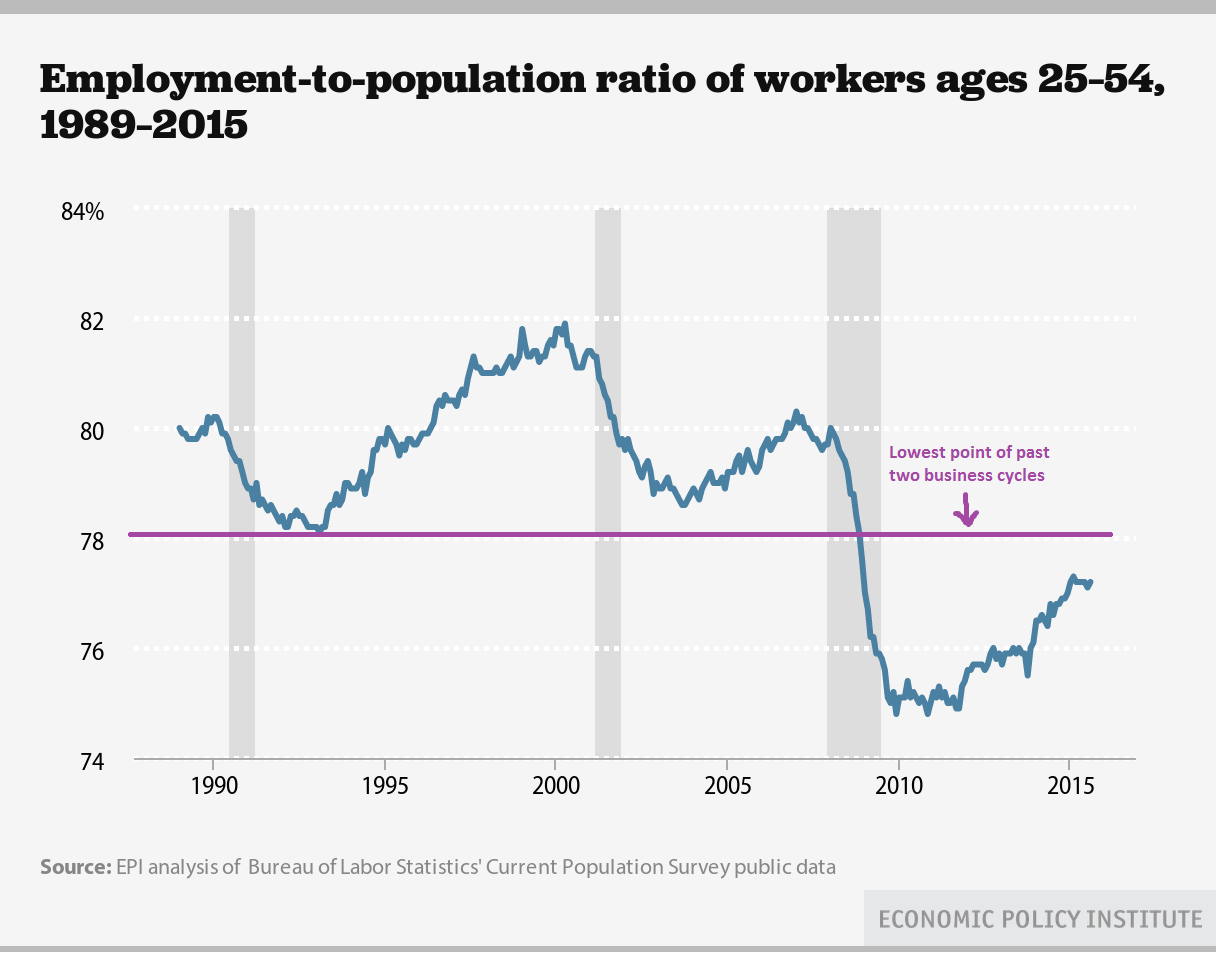

Today’s Bureau of Labor Statistics employment situation report showed the economy added a disappointing 142,000 jobs in September, bringing average monthly job creation to 198,000 in 2015—a rate slower than 2014. Hope for upward revisions to the low August numbers were dashed as well. In fact, July and August’s numbers were revised downward by a combined 59,000 fewer jobs. Digging into the report, we see that the civilian labor force participation rate declined, the employment-to-population ratio for prime age workers has continued to stagnate, (sitting at 77.2 percent—where it was when the year started), and wage growth is stuck at 2.2 percent. Taken together, these are signs of a labor market that retains a fair amount of slack and evidence that the Federal Reserve was right not to raise interest rates in September and indeed should not raise them in 2015.

With the September data in hand, we can look at the number of teachers who are starting work or going back to school this year. The number of teachers and education staff fell dramatically during the recession, and has failed to get anywhere near its prerecession level, let alone the level that would be required to keep up with an expanding student population. Along with the dismal shortfall in public sector employment, due to the Great Recession and the ensuing austerity at all levels of government, public education jobs are still 236,000 less than they were seven years ago. The number of teachers rose by 41,700 over the last year. While this is clearly a positive sign, adding in the number of public education jobs that should have been created just to keep up with enrollment, we are currently experiencing a 410,000 job shortfall in public education. Short sighted austerity measures have a measurable impact, hitting children in today’s classrooms.

Teacher employment and the number of jobs needed to keep up with enrollment, 2003–2015

| Number of jobs | Jobs needed to keep up with student enrollment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2003-01-01 | 7697400 | ||

| 2003-02-01 | 7697400 | ||

| 2003-03-01 | 7691200 | ||

| 2003-04-01 | 7698500 | ||

| 2003-05-01 | 7695000 | ||

| 2003-06-01 | 7731500 | ||

| 2003-07-01 | 7779100 | ||

| 2003-08-01 | 7725200 | ||

| 2003-09-01 | 7667500 | ||

| 2003-10-01 | 7716500 | ||

| 2003-11-01 | 7702500 | ||

| 2003-12-01 | 7703100 | ||

| 2004-01-01 | 7712000 | ||

| 2004-02-01 | 7719900 | ||

| 2004-03-01 | 7748300 | ||

| 2004-04-01 | 7753800 | ||

| 2004-05-01 | 7776700 | ||

| 2004-06-01 | 7760700 | ||

| 2004-07-01 | 7757500 | ||

| 2004-08-01 | 7766900 | ||

| 2004-09-01 | 7774300 | ||

| 2004-10-01 | 7782800 | ||

| 2004-11-01 | 7797500 | ||

| 2004-12-01 | 7803200 | ||

| 2005-01-01 | 7821900 | ||

| 2005-02-01 | 7831100 | ||

| 2005-03-01 | 7820900 | ||

| 2005-04-01 | 7829400 | ||

| 2005-05-01 | 7840200 | ||

| 2005-06-01 | 7818800 | ||

| 2005-07-01 | 7904700 | ||

| 2005-08-01 | 7907300 | ||

| 2005-09-01 | 7878700 | ||

| 2005-10-01 | 7864600 | ||

| 2005-11-01 | 7875600 | ||

| 2005-12-01 | 7883000 | ||

| 2006-01-01 | 7882200 | ||

| 2006-02-01 | 7886900 | ||

| 2006-03-01 | 7890600 | ||

| 2006-04-01 | 7896100 | ||

| 2006-05-01 | 7883900 | ||

| 2006-06-01 | 7867800 | ||

| 2006-07-01 | 7899900 | ||

| 2006-08-01 | 7935200 | ||

| 2006-09-01 | 7972600 | ||

| 2006-10-01 | 7950200 | ||

| 2006-11-01 | 7954500 | ||

| 2006-12-01 | 7956800 | ||

| 2007-01-01 | 7959800 | ||

| 2007-02-01 | 7953300 | ||

| 2007-03-01 | 7956300 | ||

| 2007-04-01 | 7965400 | ||

| 2007-05-01 | 7974300 | ||

| 2007-06-01 | 7964600 | ||

| 2007-07-01 | 7945700 | ||

| 2007-08-01 | 7991800 | ||

| 2007-09-01 | 8008600 | ||

| 2007-10-01 | 8023000 | ||

| 2007-11-01 | 8034400 | ||

| 2007-12-01 | 8054700 | ||

| 2008-01-01 | 8053500 | ||

| 2008-02-01 | 8064700 | ||

| 2008-03-01 | 8067900 | ||

| 2008-04-01 | 8062000 | ||

| 2008-05-01 | 8078100 | ||

| 2008-06-01 | 8086200 | ||

| 2008-07-01 | 8119400 | ||

| 2008-08-01 | 8091900 | ||

| 2008-09-01 | 8085300 | 8085300 | 8085300 |

| 2008-10-01 | 8089800 | 8087354 | |

| 2008-11-01 | 8082800 | 8089408 | |

| 2008-12-01 | 8083600 | 8091463 | |

| 2009-01-01 | 8084000 | 8093519 | |

| 2009-02-01 | 8096700 | 8095575 | |

| 2009-03-01 | 8093700 | 8097631 | |

| 2009-04-01 | 8091600 | 8099689 | |

| 2009-05-01 | 8088200 | 8101746 | |

| 2009-06-01 | 8108400 | 8103804 | |

| 2009-07-01 | 8066700 | 8105863 | |

| 2009-08-01 | 8061900 | 8107922 | |

| 2009-09-01 | 8012300 | 8109982 | |

| 2009-10-01 | 8073700 | 8112042 | |

| 2009-11-01 | 8099100 | 8114103 | |

| 2009-12-01 | 8071600 | 8116164 | |

| 2010-01-01 | 8068500 | 8118226 | |

| 2010-02-01 | 8057000 | 8120288 | |

| 2010-03-01 | 8058000 | 8122351 | |

| 2010-04-01 | 8056300 | 8124414 | |

| 2010-05-01 | 8062400 | 8126478 | |

| 2010-06-01 | 8048600 | 8128542 | |

| 2010-07-01 | 8026300 | 8130607 | |

| 2010-08-01 | 7997100 | 8132673 | |

| 2010-09-01 | 7919200 | 8134739 | |

| 2010-10-01 | 7963700 | 8136805 | |

| 2010-11-01 | 7961500 | 8138872 | |

| 2010-12-01 | 7953500 | 8140940 | |

| 2011-01-01 | 7948000 | 8143008 | |

| 2011-02-01 | 7930300 | 8145076 | |

| 2011-03-01 | 7927500 | 8147146 | |

| 2011-04-01 | 7939600 | 8149215 | |

| 2011-05-01 | 7897600 | 8151285 | |

| 2011-06-01 | 7925400 | 8153356 | |

| 2011-07-01 | 7866900 | 8155427 | |

| 2011-08-01 | 7845400 | 8157499 | |

| 2011-09-01 | 7793600 | 8159571 | |

| 2011-10-01 | 7829100 | 8161644 | |

| 2011-11-01 | 7815800 | 8163718 | |

| 2011-12-01 | 7807900 | 8165791 | |

| 2012-01-01 | 7801400 | 8167866 | |

| 2012-02-01 | 7805000 | 8169941 | |

| 2012-03-01 | 7796400 | 8172016 | |

| 2012-04-01 | 7773900 | 8174092 | |

| 2012-05-01 | 7772000 | 8176169 | |

| 2012-06-01 | 7740800 | 8178246 | |

| 2012-07-01 | 7774700 | 8180323 | |

| 2012-08-01 | 7794400 | 8182401 | |

| 2012-09-01 | 7764400 | 8184480 | |

| 2012-10-01 | 7757600 | 8186559 | |

| 2012-11-01 | 7751900 | 8188639 | |

| 2012-12-01 | 7774300 | 8190719 | |

| 2013-01-01 | 7775600 | 8192800 | |

| 2013-02-01 | 7776800 | 8194881 | |

| 2013-03-01 | 7773600 | 8196963 | |

| 2013-04-01 | 7758800 | 8199045 | |

| 2013-05-01 | 7773400 | 8201128 | |

| 2013-06-01 | 7737300 | 8203211 | |

| 2013-07-01 | 7763800 | 8205295 | |

| 2013-08-01 | 7801400 | 8207379 | |

| 2013-09-01 | 7777800 | 8209464 | |

| 2013-10-01 | 7776800 | 8211550 | |

| 2013-11-01 | 7779000 | 8213636 | |

| 2013-12-01 | 7763700 | 8215722 | |

| 2014-01-01 | 7765000 | 8217809 | |

| 2014-02-01 | 7765400 | 8219897 | |

| 2014-03-01 | 7769000 | 8221985 | |

| 2014-04-01 | 7781900 | 8224074 | |

| 2014-05-01 | 7774200 | 8226163 | |

| 2014-06-01 | 7786500 | 8228253 | |

| 2014-07-01 | 7799200 | 8230343 | |

| 2014-08-01 | 7804500 | 8232434 | |

| 2014-09-01 | 7807600 | 8234525 | |

| 2014-10-01 | 7799500 | 8236617 | |

| 2014-11-01 | 7797400 | 8238709 | |

| 2014-12-01 | 7796700 | 8240802 | |

| 2015-01-01 | 7797200 | 8242896 | |

| 2015-02-01 | 7791400 | 8244990 | |

| 2015-03-01 | 7790200 | 8247084 | |

| 2015-04-01 | 7784600 | 8249179 | |

| 2015-05-01 | 7789200 | 8251275 | |

| 2015-06-01 | 7810600 | 8253371 | |

| 2015-07-01 | 7829000 | 8255467 | |

| 2015-08-01 | 7849300 | 8257565 | |

| 2015-09-01 | 7849300 | 8259662 | 8085300 |

Source: EPI analysis of Current Employment Statistics public data series and U.S. Department of Education (2014)

What to Watch on Jobs Day: The Teacher Gap, Wages, and Prime-age EPOP

On Friday, the Bureau of Labor Statistics will release the September numbers on the state of the labor market. I will be watching for upward revisions to August’s employment numbers, which came in lower than expected. As usual, I’ll be paying close attention to the prime-age employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) and nominal wages, which are two of the best indicators of labor market health. Friday’s report will also give us a chance to examine the “teacher gap”— the gap between actual local public education employment and what is needed to keep up with growth in the student population

Prime-age EPOP—the share of the working age population who is actually working—fell dramatically during the Great Recession. It saw some solid increases once the recovery began to take hold, but unfortunately remains below the lowest point of the past two business cycles and has stagnated for much of this year, as job growth has only been fast enough to keep up with the growth of the working age population. Before we can say that the labor market is truly back to normal, we need to see faster job growth—to employ new labor market entrants, unemployed workers, and the 3+ million missing workers who have left or never entered the labor market because of weak job opportunities.

New Scandals Revealed by the New York Times: How the H-1B Visa is Used to Ship American Jobs Overseas

The New York Times has a front page story today about three new cases of H-1B abuse as a follow-up to the Disney scandal it reported on in June. This one, too, features household names: Toys R Us and New York Life. It also includes academic publishing powerhouse, Cengage, whose textbooks are used in college campuses across the country. Those companies have been outsourcing work to companies with track records as major H-1B abusers that use the program to ship jobs overseas: Accenture, TCS, and Cognizant.

The Times story, written by Julia Preston, outlines a process I have written quite a bit about over the years: how the H-1B program, which Congress created to help U.S. companies fill jobs here in the United States, is actually used to facilitate the shipping of American jobs overseas to low-cost countries like India. This, in fact, is the most common use of the H-1B program, which India’s Commerce Minister Kamal Nath dubbed the “outsourcing visa” in 2007.

Preston reports that Tata Consultancy Services sent Indian workers to a Toys R Us facility in New Jersey, where they shadowed U.S. accounting employees, learning their jobs and writing up manuals to train employees back in India how to do the same work and replace the U.S. employees. The result was unemployment for middle-class, middle-aged Americans and the loss of 67 jobs in New Jersey. A company spokesperson was unapologetic, telling the Times that the outsourcing “resulted in significant cost savings.”

The Case Against Raising Interest Rates Before Wage Growth Picks Up

This piece originally appeared in the Wall Street Journal’s Think Tank blog.

I’ve been arguing for the past year that until nominal wage growth picks up considerably, the Federal Reserve has little to fear about price inflation being pushed above its 2 percent target. The logic of focusing on wage growth is pretty easy to explain.

First, note that nominal (i.e., not inflation-adjusted) wage growth can rise as fast as economy-wide productivity without putting any upward pressure on prices. Say that both nominal wages and productivity rose 2 perecnt in a year. What would happen to the cost per unit of output? It would not rise at all. Hourly wages would climb 2 percent, but the amount produced in each hour of work—the definition of productivity—would also rise by 2 percent, so costs per unit of output (or, prices) would not budge. If we assume that trend productivity growth in the U.S. economy is roughly 1.5 percent per year, this means that only nominal wage growth faster than 1.5 percent puts any upward pressure on prices.

Now, the Fed isn’t committed to zero upward pressure on prices. Fed officials say they’re comfortable with 2 percent inflation. (I’d argue that they should be comfortable with inflation well above that, up to 5 percent, but we’ll take their target for now.) This price target means that nominal wage growth can be 2 percent higher than trend productivity growth before wages threaten to push inflation over the Fed’s target. We would need to see nominal wage growth of 3.5 percent, substantially higher than what it has been since the recovery began, before labor costs start threatening to push inflation beyond the Fed’s comfort zone. (There is a handy nominal wage tracker on the Economic Policy Institute’s website that covers a lot of this ground.)

All that said, in a speech last week, Federal Reserve Chairwoman Janet Yellen included a footnote that argued against the relevance of wage targeting. The upshot was this sentence: “More generally, movements in labor costs no longer appear to be an especially good guide to future price movements.” This footnote reinforced other recent statements from Dr. Yellen that seem to leave the door open to the Fed tightening well before any increase in nominal wages shows up in the data. I would argue that this is almost exactly wrong.

Disability and Employment Revisited

Alarming statistics that show large declines in the employment and labor force participation of Americans with disabilities are often cited to support the claim that workers in poor health but able to work are increasingly opting out of the workforce to claim disability benefits. However, these statistics don’t account for a weak labor market, an aging population, the rise in women’s labor force participation, or problems with self-reported disability measures. If one takes these factors into account, there’s no evidence that more workers with comparatively mild impairments are exiting the workforce to claim disability benefits.

The American Institutes of Research (AIR) has a new report by Michelle Yin and Dahlia Shaewitz showing that the labor force participation of Americans with disabilities fell from 25 percent in 2001 to 16 percent in 2014, based on data from the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau (CPS-ASEC—henceforth CPS). Tying this to a broader decline in the labor force participation of working-age adults, the authors warn that “this situation leaves the United States with an even smaller pool of workers to support the recovering economy. “

In the same vein, a recent op-ed in the Wall Street Journal by Andrew Biggs of the American Enterprise Institute cites a “nearly 50 percent decline in the employment rate of Americans with disabilities since 1981.” Echoing critiques of the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program I’ve discussed in earlier blog posts, Biggs attributes the problem to “looser eligibility standards and stagnating wages that made disability benefits, averaging $1,222 a month for new beneficiaries last year, more attractive relative to work for the less-skilled.” Though Yin and Shaewitz appear more concerned with the plight of people with disabilities than with criticizing SSDI, they also suggest that the “growing number of discouraged workers with disabilities may be a result of policies that unintentionally make it easier to leave the workforce or stay out altogether.”

Pope Francis reminds us that our economic systems should reflect our moral values

During his first visit to the United States, Pope Francis is expected to address economic issues like inequality and poverty, continuing his criticism of trickle-down economic policy. These are issues that affect the lives of everyday Americans: wages for the vast majority of workers in the United States have been stagnant for 35 years despite growing productivity, lawmakers continue to chip away at workers’ right to unionize, and the gulf between top earners and the rest of the nation continues to grow.

While many have lauded Pope Francis for consistently discussing economic inequality and poverty, some on the right have been less enthusiastic. In response to the pope’s encyclical on poverty and the environment, Jeb Bush, for example, remarked, “I don’t get economic policy from my bishops or my cardinal or my pope. I think religion ought to be about making us better as people and less about things that end up getting in the political realm.”

Bush’s dismissal of the pope’s positions on economic issues not only contradicts his earlier claims about the relationship between religion and politics, but also ignores the history of his own church. Far from emerging from a vacuum, Pope Francis is continuing a tradition of Catholic social teaching that stretches back to Pope Leo XIII’s 1891 encyclical on the conditions facing working people. And this attempt to respond to economic and labor issues from a Christian framework is also not solely Catholic. At the same time Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical entered the intellectual sphere, American Protestants like Washington Gladden (a pastor and prominent early thinker of what would become the Social Gospel) were also working to address the conditions of working people through Christianity.

In Virtually Every State, the Poverty Rate is Still Higher than Before the Recession

Between 2013 and 2014, the poverty rate in most states was largely unchanged, according to yesterday’s release of state poverty statistics from the American Community Survey (ACS). While the poverty rate fell slightly for the country as a whole, most of the changes at the state level were too small to signify a meaningful difference. As of 2014, only two states—North Dakota and Colorado—have poverty rates at or below their 2007 values, before the Great Recession.

From 2013 to 2014, the national poverty rate, as measured by the ACS, fell from 15.8 percent to 15.5 percent. Poverty rates declined in 34 states plus the District of Columbia, but only five of these changes were large enough to signify a measurable difference: Mississippi (-2.5 percentage points), Colorado (-1.0 percentage points), Washington, (-0.9 percentage points), Michigan (-0.8 percentage points), and North Carolina (-0.7 percentage points). (A number of other states had similar reductions in their poverty rates, but the sample sizes for these states are too small to tell whether these changes were statistically significant.) Alaska was the only state where the poverty rate increased significantly, rising from 9.3 percent to 11.2 percent.

The lack of improvement in state poverty rates echoes the trends we’ve seen in household income. However, the data suggest that the lack of real income growth over the past decade and a half has been even more pronounced for households at the bottom of the income scale. As of 2014, 38 states had lower median household income than in 2000, yet 47 states—nearly the entire country—had higher poverty rates in 2014 than in 2000.

State-Level Data Show Incomes Continue to Stagnate in Households Across the Map

Thursday’s release of state income data from the American Community Survey (ACS) showed that the gradual improvement in state economies from 2013 to 2014 brought little change in overall economic conditions for households in most states. The ACS data showed a slight increase in median household income for the United States overall and similar modest increases in household incomes in a majority of states—although only a handful of these increases were statistically significant.

By and large, what little improvement in household incomes occurred tended to be in states where incomes were already relatively high or where the oil and gas boom has fueled growth. Higher income states in New England and the mid-Atlantic, as well as Washington state, experienced modest gains, while incomes elsewhere were essentially flat. Kentucky (-2.6 percent) was the only state where household incomes significantly fell.

After adjusting for inflation, the largest year-over-year percentage gains occurred in Maine (+3.6 percent), Washington (+3.4 percent), Connecticut (+2.7 percent), and Colorado (+2.5 percent). The District of Columbia (+4.3 percent), North Dakota (+4.2 percent), and Mississippi (+2.8 percent) also had relatively large increases, although these changes were not statistically significant.

Workers 65 and Older Are 3 Times as Likely to Die From an On-the-Job Injury as the Average Worker

As the Boomers age and retirement insecurity forces workers to delay retirement, workers 55 and older are a growing part of the workforce. In 2014, older workers were 21 percent of the adult workforce based on hours worked—8 percentage points higher than their 13 percent share in 2000.

One unfortunate effect of this increased labor force participation is an increased exposure to workplace hazards, and with hazards come injuries and even death. Older workers are much more likely to be the victims of fatal occupational injuries than are younger workers. In 2014, nearly 35 percent of all fatal on-the-job injuries (1,621 of 4,679) occurred among the 21 percent of the workforce age 55 or older. The fatality rate for workers 65 and older is especially high—three times that of the overall workforce.

In the last year there was an alarming 9 percent increase in fatal workplace injuries among workers 55 and older, and a 17.7 percent increase among workers 65 and older. Nationwide, among all age groups, fatal workplace injuries rose from 4,585 in 2013 to 4,679 in 2014, an increase of 94 deaths. The increase in deaths among workers age 65 and older more than accounted for the entire increase in fatal on-the-job injuries.

Poverty Day Numbers Show the Need for Higher Wages

This post originally appeared on Spotlight on Poverty and Opportunity.

This morning, the US Census Bureau released annual income and poverty data showing essentially no change in the economic status of low- and middle-income households from 2013 to 2014. Despite an improving economy, the same proportion of Americans is still struggling to make ends meet. This lack of improvement in the poverty rate illustrates one of the chief catalysts behind America’s persistent poverty: stagnant wage growth that has left too many people without the means to support themselves and their families.

The official US poverty rate for 2014 was 14.8 percent. This is slightly higher than the official poverty rate reported for 2013 last year; however, last year the Census Bureau redesigned the survey that determines the poverty rate. For last year’s release, Census used both the new and old surveys in parallel, but only reported the results from the old survey. This year, they released the 2013 values from the new survey, which showed a poverty rate in 2013 of 14.8 percent—the same rate reported for 2014 in this year’s release. In 2014, the share of the population in deep poverty – with incomes less than half the poverty line – was 6.6 percent, and the share of families with income less than twice the poverty line was 33.4 percent.

This is the second year in a row that the Census Bureau’s statistics have shown that 1 in 7 American families – roughly 47 million people – have incomes too low to meet the government’s official threshold for basic subsistence, a measure long recognized as inadequate for assessing true economic need. For 2014, the poverty line for a family of four was $24,418; alternative measures show that families require far higher levels of income to achieve modest economic security, even in the country’s least expensive areas.

Wrong Question Answered Badly: Industry Data Can’t Be Used To Infer Individuals’ Productivity

In the debate over the relationship between economy-wide productivity and typical workers’ pay the numbers are clear: typical workers’ pay hasn’t come close to keeping up with productivity, and a wide gap between the two has developed. There has been no credible challenge to this basic finding.

Some have moved past the debate over the numbers to argue that this divergence is not a sign that the economy, and economic policy, is failing these workers. Instead, they argue that the underlying productivity of most workers must have stagnated, and that it is their productivity stagnation that has driven their wage stagnation. This essentially argues that relatively stagnant pay for typical workers is because most Americans are no more productive now than decades ago, and hence did not deserve to see gains in hourly pay in recent decades. A corollary to this argument is the notion that the pay and productivity divergence therefore requires no policy response other than attempting to raise workers’ productivity.

We noted in our recent paper the glaring lack of any actual evidence for the claim that most workers have not become more productive in the past three decades. In fact, most evidence (which we’ll highlight a bit later) indicates that most American workers have become substantially more productive over time. However, in a recent blog post, Evan Soltas claims to have marshalled evidence indicating that most American workers have not seen productivity gains in recent years. Soltas’ conclusion that most American workers must not have become more productive in recent decades is predicated upon looking at industry-level measures of productivity and average pay. He claims to have found a strong correlation between the growth of industry productivity and industry pay, and then claims this (somehow) implies that we know the divergence between economy-wide productivity and typical workers’ pay must, therefore, have been driven by the failure of typical workers to become more productive in recent decades.

We explain in this post why his suggested empirical test for assessing this question is actually meaningless, and will also show how the execution of his test is flawed, and his empirical conclusions (which would be irrelevant in any case) are false. Estimated correctly, there is no correlation between industry productivity and average industry pay. More importantly, even if there was such a correlation, this would be entirely uninformative about the underlying productivity of individuals. In short, Soltas asked the wrong question and then answered it incorrectly.

The Real Stakes for This Week’s Fed Decision on Interest Rates

This piece originally appeared in the Wall Street Journal’s Think Tank blog.

The case against the Federal Reserve raising short-term interest rates at the end of the Federal Open Market Committee meetings Thursday is so clearly strong that is should carry the day. The point of raising rates is to rein in an overheating economy that is threatening to push inflation outside the Fed’s comfort zone. But inflation has been running below the Fed’s target for years—and its recent moves have been down, not up.

This subdued price inflation is not a puzzle; it’s the outcome of a labor market that remains so slack that nominal wage growth is running about half as fast as a healthy recovery would be churning out. And this slack is pretty easy to see so long as one is willing to look past the (welcome) progress in reducing the headline unemployment rate. The employment-to-population ratio of prime-age adults (25 to 54 years old) has recovered less than half of its decline during the Great Recession. Worse, progress in boosting this measure has stalled for all of 2015.

Nominal wage growth has been far below target in the recovery: Year-over-year change in private-sector nominal average hourly earnings, 2007-2016

| All nonfarm employees | Production/nonsupervisory workers | |

|---|---|---|

| Mar-2007 | 3.59% | 4.11% |

| Apr-2007 | 3.27% | 3.85% |

| May-2007 | 3.73% | 4.14% |

| Jun-2007 | 3.81% | 4.13% |

| Jul-2007 | 3.45% | 4.05% |

| Aug-2007 | 3.49% | 4.04% |

| Sep-2007 | 3.28% | 4.15% |

| Oct-2007 | 3.28% | 3.78% |

| Nov-2007 | 3.27% | 3.89% |

| Dec-2007 | 3.16% | 3.81% |

| Jan-2008 | 3.11% | 3.86% |

| Feb-2008 | 3.09% | 3.73% |

| Mar-2008 | 3.08% | 3.77% |

| Apr-2008 | 2.88% | 3.70% |

| May-2008 | 3.02% | 3.69% |

| Jun-2008 | 2.67% | 3.62% |

| Jul-2008 | 3.00% | 3.72% |

| Aug-2008 | 3.33% | 3.83% |

| Sep-2008 | 3.23% | 3.64% |

| Oct-2008 | 3.32% | 3.92% |

| Nov-2008 | 3.64% | 3.85% |

| Dec-2008 | 3.58% | 3.84% |

| Jan-2009 | 3.58% | 3.72% |

| Feb-2009 | 3.24% | 3.65% |

| Mar-2009 | 3.13% | 3.53% |

| Apr-2009 | 3.22% | 3.29% |

| May-2009 | 2.84% | 3.06% |

| Jun-2009 | 2.78% | 2.94% |

| Jul-2009 | 2.59% | 2.71% |

| Aug-2009 | 2.39% | 2.64% |

| Sep-2009 | 2.34% | 2.75% |

| Oct-2009 | 2.34% | 2.63% |

| Nov-2009 | 2.05% | 2.67% |

| Dec-2009 | 1.82% | 2.50% |

| Jan-2010 | 1.95% | 2.61% |

| Feb-2010 | 2.00% | 2.49% |

| Mar-2010 | 1.77% | 2.27% |

| Apr-2010 | 1.81% | 2.43% |

| May-2010 | 1.94% | 2.59% |

| Jun-2010 | 1.71% | 2.53% |

| Jul-2010 | 1.85% | 2.47% |

| Aug-2010 | 1.75% | 2.41% |

| Sep-2010 | 1.84% | 2.30% |

| Oct-2010 | 1.88% | 2.51% |

| Nov-2010 | 1.65% | 2.23% |

| Dec-2010 | 1.74% | 2.07% |

| Jan-2011 | 1.92% | 2.17% |

| Feb-2011 | 1.87% | 2.12% |

| Mar-2011 | 1.87% | 2.06% |

| Apr-2011 | 1.91% | 2.11% |

| May-2011 | 2.00% | 2.16% |

| Jun-2011 | 2.13% | 2.00% |

| Jul-2011 | 2.26% | 2.31% |

| Aug-2011 | 1.90% | 1.99% |

| Sep-2011 | 1.94% | 1.93% |

| Oct-2011 | 2.11% | 1.77% |

| Nov-2011 | 2.02% | 1.77% |

| Dec-2011 | 1.98% | 1.77% |

| Jan-2012 | 1.75% | 1.40% |

| Feb-2012 | 1.88% | 1.45% |

| Mar-2012 | 2.10% | 1.76% |

| Apr-2012 | 2.01% | 1.76% |

| May-2012 | 1.83% | 1.39% |

| Jun-2012 | 1.95% | 1.54% |

| Jul-2012 | 1.77% | 1.33% |

| Aug-2012 | 1.82% | 1.33% |

| Sep-2012 | 1.99% | 1.44% |

| Oct-2012 | 1.51% | 1.28% |

| Nov-2012 | 1.90% | 1.43% |

| Dec-2012 | 2.20% | 1.74% |

| Jan-2013 | 2.15% | 1.89% |

| Feb-2013 | 2.10% | 2.04% |

| Mar-2013 | 1.93% | 1.88% |

| Apr-2013 | 2.01% | 1.73% |

| May-2013 | 2.01% | 1.88% |

| Jun-2013 | 2.13% | 2.03% |

| Jul-2013 | 1.91% | 1.92% |

| Aug-2013 | 2.26% | 2.18% |

| Sep-2013 | 2.04% | 2.17% |

| Oct-2013 | 2.25% | 2.27% |

| Nov-2013 | 2.24% | 2.32% |

| Dec-2013 | 1.90% | 2.16% |

| Jan-2014 | 1.94% | 2.31% |

| Feb-2014 | 2.14% | 2.45% |

| Mar-2014 | 2.18% | 2.40% |

| Apr-2014 | 1.97% | 2.40% |

| May-2014 | 2.13% | 2.44% |

| Jun-2014 | 2.04% | 2.34% |

| Jul-2014 | 2.09% | 2.43% |

| Aug-2014 | 2.21% | 2.48% |

| Sep-2014 | 2.04% | 2.27% |

| Oct-2014 | 2.03% | 2.27% |

| Nov-2014 | 2.11% | 2.26% |

| Dec-2014 | 1.82% | 1.87% |

| Jan-2015 | 2.23% | 2.01% |

| Feb-2015 | 2.06% | 1.71% |

| Mar-2015 | 2.18% | 1.90% |

| Apr-2015 | 2.34% | 2.00% |

| May-2015 | 2.34% | 2.14% |

| Jun-2015 | 2.04% | 1.99% |

| Jul-2015 | 2.29% | 2.04% |

| Aug-2015 | 2.32% | 2.08% |

| Sep-2015 | 2.40% | 2.13% |

| Oct-2015 | 2.52% | 2.36% |

| Nov-2015 | 2.39% | 2.21% |

| Dec-2015 | 2.60% | 2.61% |

| Jan-2016 | 2.50% | 2.50% |

| Feb-2016 | 2.38% | 2.50% |

| Mar-2016 | 2.33% | 2.44% |

| Apr-2016 | 2.49% | 2.53% |

| May-2016 | 2.48% | 2.33% |

| Jun-2016 | 2.64% | 2.48% |

| Jul-2016 | 2.72% | 2.57% |

| Aug-2016 | 2.43% | 2.46% |

| Sep-2016 | 2.59% | 2.65% |

*Nominal wage growth consistent with the Federal Reserve Board's 2 percent inflation target, 1.5 percent productivity growth, and a stable labor share of income.

Source: EPI analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Employment Statistics public data series

Many have asked: Would a 0.25 percent increase really do all that much harm? This is the wrong question. The literal, narrow-minded answer is: No, it wouldn’t do much harm. But the data above show that the Fed should not be tightening at all. A 0.25 percent increase is a small move in the wrong direction—but it’s still the wrong way to go.

New Census Data Show No Progress in Closing Stubborn Racial Income Gaps

Today’s Census Bureau report on income, poverty and health insurance coverage in 2014 shows that with the exception of non-Hispanic white households, median household incomes were not statistically different from 2013. Measured incomes increased among Latino (+$2,162, 5.4 percent) and Asian (+$744, 1.0 percent) households, but declined for African-American (-$497, 1.4 percent) and non-Hispanic white households (-$1,048, 1.7 percent). As a result, no progress was made in closing the black-white income gap between 2013 and 2014—the median black household has just 59 cents for every dollar of white median household income. The Hispanic-white income gap narrowed from 66 to 71 cents on the dollar. Weak income growth between 2013 and 2014 also leaves real median household incomes for all groups well below their 2007 levels. Between 2007 and 2014, median household incomes declined by 10.5 percent (-$4,137) for African Americans, 0.7 percent (-$294) for Latinos, 7.2 percent (-$4,662) for whites, and 8.8 percent (-$7,158) for Asians. Asian households continue to have the highest median income in spite of large income losses in the wake of the recession.

Note: CPS ASEC changed its methodology for data years 2013 and 2014, hence the break in the series in 2013. Solid lines are actual CPS ASEC data; dashed lines denote historical values imputed by applying the new methodology to past income trends. White refers to non-Hispanic whites, black refers to blacks alone, Asian refers to Asians alone, and Hispanic refers to Hispanics of any race. Comparable data are not available prior to 2002 for Asians. Shaded areas denote recessions. To account for the redesign of the CPS ASEC survey, when the difference between the original data for 2013 and the redesigned data for 2013 is small in magnitude (less than a 1 percent difference) and statistically insignificantly different, data for 2013 is an average of the original and redesigned data. When the difference between them is relatively large in magnitude (1 percent or greater) or statistically significantly different, we display a break in the series and impute the ratio between them to historical data. Source: EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement Historical Poverty Tables (Table H-5 and H-9)Real median household income, by race and ethnicity, 2000–2014

Year

White

Black

Hispanic

Asian

White-imputed

Black-imputed

Hispanic-imputed

Asian

White

Black

Hispanic

Asian

2000

$62,716

$40,782

$45,594

$64,932

$41,638

$44,174

2001

$61,914

$39,404

$44,879

$64,101

$40,231

$43,481

2002

$61,724

$38,201

$43,566

$69,260

$63,905

$39,002

$42,209

$74,752

2003

$61,484

$38,150

$42,464

$71,679

$63,657

$38,951

$41,141

$77,363

2004

$61,294

$37,715

$42,949

$72,064

$63,460

$38,507

$41,611

$77,779

2005

$61,570

$37,412

$43,606

$74,070

$63,746

$38,197

$42,248

$79,943

2006

$61,560

$37,541

$44,366

$75,434

$63,735

$38,329

$42,984

$81,415

2007

$62,703

$38,722

$44,160

$75,471

$64,918

$39,535

$42,785

$81,455

2008

$61,056

$37,623

$41,686

$72,169

$63,213

$38,413

$40,387

$77,891

2009

$60,093

$35,953

$41,972

$72,239

$62,216

$36,708

$40,665

$77,967

2010

$59,125

$34,876

$40,855

$69,764

$61,215

$35,608

$39,582

$75,296

2011

$58,319

$33,920

$40,650

$68,545

$60,379

$34,631

$39,384

$73,981

2012

$58,781

$34,357

$40,217

$70,769

$60,858

$35,078

$38,965

$76,381

2013

$59,212

$35,157

$41,625

$68,149

$61,304

$35,895

$40,329

$73,553

$61,304

$35,895

$40,329

$73,553

2014

$60,256

$35,398

$42,491

$74,297

The primary driving force behind the slow recovery of pre-recession income levels has been stagnant wage growth. Wages have remained essentially flat since 2000, and despite relatively strong job growth in 2014, wages were remarkably unchanged. From the start of the recovery in 2009 through 2014, real earnings of men working full-time, full-year were down for white (-1.5 percent) and Hispanic (-1.5 percent) men, but up for black men (+1.2 percent). As a result, the black-white and Hispanic-white male earnings gaps are unchanged. Black men earned 70 cents for every dollar earned by white men in 2014 (compared to 69 cents/dollar in 2009) and Hispanic men earned 60 cents on the dollar.

Note: Earnings are wage and salary income. White refers to non-Hispanic whites, black refers to blacks alone, and Hispanic refers to Hispanics of any race. Asians are excluded from this figure due to the volatility of the series. Shaded areas denote recessions. To account for the redesign of the CPS ASEC survey, when the difference between the original data for 2013 and the redesigned data for 2013 is small in magnitude (less than a 1 percent difference) and statistically insignificantly different, data for 2013 is an average of the original and redesigned data. When the difference between them is relatively large in magnitude (1 percent or greater) or statistically significantly different, we display a break in the series and impute the ratio between them to historical data. Source: EPI analysis of Annual Social and Economic Supplement Historical Income Tables (Table PINC-07)Real earnings of full-time, full-year male workers, by race and ethnicity, 2000–2014

Year

Hispanic

White

Black

2000

$43,297

$75,622

$50,021

2001

$43,233

$75,262

$50,056

2002

$44,993

$75,748

$51,204

2003

$42,687

$75,236

$50,700

2004

$43,455

$74,844

$48,483

2005

$42,785

$75,413

$50,360

2006

$43,159

$74,870

$50,088

2007

$43,194

$73,918

$48,115

2008

$44,018

$74,947

$50,067

2009

$45,072

$75,246

$51,616

2010

$44,822

$75,107

$49,494

2011

$43,511

$75,460

$52,665

2012

$44,386

$75,099

$50,186

2013

$44,438

$73,613

$52,300

2014

$44,383

$74,108

$52,236

By the Numbers: Income and Poverty, 2014

Key numbers from today’s new Census reports, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2014 and Health Insurance in the United States: 2014. All dollar values are adjusted for inflation (2014 dollars).

Earnings

Median earnings for men working full time fell 0.7 percent from 2000 to 2013. In 2014 men’s earnings fell 0.9 percent, to $50,383.

Median earnings for women working full time rose 5.4 percent from 2000 to 2013. In 2014 women’s earnings rose 0.5 percent, to $39,621.

Median earnings for men working full-time

- 2014: $50,383

- 2000–2013: -0.7%

- 2013–2014: -0.9%

Median earnings for women working full-time

- 2014: $39,621

- 2000–2013: 5.4%

- 2013–2014: 0.5%

Income Stagnation in 2014 Shows the Economy Is Not Working for Most Families

We learned from the Census Bureau this morning that the decent employment growth in 2014 yielded no improvements in wages and, not surprisingly, no improvement in the median incomes of working-age households or drop in the number of people living in poverty. Wage trends greatly determine how fast incomes at the middle and bottom grow, as well as the overall path of income inequality, as we argued in Raising America’s Pay. This is for the simple reason that most households, including those with low incomes, rely on labor earnings for the vast majority of their income.

The Census data show that from 2013–2014, median household income for non-elderly households (those with a head of household younger than 65 years old) decreased 1.3 percent from $61,252 to $60,462. This decrease unfortunately exacerbates the trend of losses incurred during the Great Recession and the losses that prevailed in the prior business cycle from 2000–2007. Median household income for non-elderly households in 2014 ($60,462) was 9.2 percent, or $6,113, below its level in 2007. The disappointing trends of the Great Recession and its aftermath come on the heels of the weak labor market from 2000–2007, during which the median income of non-elderly households fell significantly from $68,941 to $66,575, the first time in the post-war period that incomes failed to grow over a business cycle. Altogether, from 2000–2014, the median income for non-elderly households fell from $68,941 to $60,462, a decline of $8,479, or 12.3 percent.

Real median household income, all and non-elderly, 1995–2014

| All households | All households- imputed series | All households- new series | Non-elderly households | Non-elderly households- imputed series | Non-elderly households- new series | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995-01-01 | $52,555 | $54,231 | $60,378 | $62,268 | ||

| 1996-01-01 | $53,319 | $55,020 | $61,506 | $63,431 | ||

| 1997-01-01 | $54,417 | $56,152 | $62,298 | $64,248 | ||

| 1998-01-01 | $56,394 | $58,193 | $64,823 | $66,852 | ||

| 1999-01-01 | $57,815 | $59,659 | $66,493 | $68,575 | ||

| 2000-01-01 | $57,718 | $59,559 | $66,849 | $68,941 | ||

| 2001-01-01 | $56,460 | $58,261 | $65,819 | $67,879 | ||

| 2002-01-01 | $55,801 | $57,580 | $65,145 | $67,184 | ||

| 2003-01-01 | $55,752 | $57,530 | $64,573 | $66,594 | ||

| 2004-01-01 | $55,558 | $57,330 | $63,816 | $65,814 | ||

| 2005-01-01 | $56,172 | $57,963 | $63,399 | $65,384 | ||

| 2006-01-01 | $56,589 | $58,394 | $64,250 | $66,261 | ||

| 2007-01-01 | $57,348 | $59,177 | $64,554 | $66,575 | ||

| 2008-01-01 | $55,303 | $57,067 | $62,436 | $64,391 | ||

| 2009-01-01 | $54,933 | $56,685 | $61,603 | $63,532 | ||

| 2010-01-01 | $53,497 | $55,203 | $60,012 | $61,890 | ||

| 2011-01-01 | $52,680 | $54,360 | $58,559 | $60,392 | ||

| 2012-01-01 | $52,595 | $54,272 | $59,127 | $60,978 | ||

| 2013-01-01 | $52,779 | $54,462 | $54,462 | $59,393 | $61,252 | $61,252 |

| 2014-01-01 | $53,657 | $60,462 |

Note: CPS ASEC changed its methodology for data years 2013 and 2014, hence the break in the series in 2013. Solid lines are actual CPS ASEC data; dashed lines denote historical values imputed by applying the new methodology to past income trends. Non-elderly households are those in which the head of household is younger than age 65. Shaded areas denote recessions.

To account for the redesign of the CPS ASEC survey, when the difference between the original data for 2013 and the redesigned data for 2013 is small in magnitude (less than a 1 percent difference) and statistically insignificantly different, data for 2013 is an average of the original and redesigned data. When the difference between them is relatively large in magnitude (1 percent or greater) or statistically significantly different, we display a break in the series and impute the ratio between them to historical data.

Source: EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement Historical Income Tables (Tables H-5 and HINC-02)

What to Watch in the Census Poverty and Income Data

On Wednesday, the Census Bureau will release the latest data on income, poverty, and health insurance coverage. As EPI’s research team eagerly awaits this release, there are a few things we will be watching for.

Due to a redesign of the underlying survey (the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement, or CPS ASEC) in 2014, current estimates of incomes and poverty will not be directly comparable to years prior to 2013. This will also be a problem, albeit to a much lesser extent, with data on labor earnings. Since the Census Bureau will provide 2013 estimates based on both the old survey and the redesigned survey, we plan to deal with the break in the data series by focusing on two time periods. The first time period will cover 2000–2013, based on estimates from the old survey format. The second will be based on the redesigned estimates for 2013–2014. While in much of our analysis we will impute recent changes onto the data back to 2000 to get a better sense in that longer term trend, we will provide clear guidance on how the survey redesign affects these trends.

On Wednesday, we are going to most closely examine median earnings for men and women, median household income, and poverty rates. We will be looking not only at what we expect to be some improvement in these metrics between 2013 and 2014, but also what’s been happening since 2000. We know that even in the full business cycle 2000-07, earnings and incomes never fully recovered pre-recession peaks, and when the Great Recession hit, the economic impacts were devastating for many. To the extent the data will allow, we will look at how much the recovery has helped improve the economic lot for Americans, with particular attention to livelihood across racial and ethnic groups.

There’s More to Economic Security than the Official Poverty Measure

Next week, the Census Bureau will release its estimates of the number of Americans who lived in poverty in 2014. The official poverty measure is an important metric—particularly since it’s been in place for nearly 50 years, and its measurement methodology hasn’t had major revisions over that time. As shown in the figure below, the share of Americans living at or below the official poverty line fell in the 1960s and stayed within a small range over the last four decades or so, generally rising in recessions and falling in expansions. Since 2000, the official poverty rate has seen a lot more up than down—the poverty rate at the end of the business cycle in 2007 was higher than at the beginning. 2013 was the first year the poverty rate turned the corner and saw some meaningful improvement since the start of the Great Recession. On Wednesday, September 16, we will see whether that progress has continued. While it would be great to see reductions in poverty over the last year, the fact is had economic growth over the last four decades been broadly shared, we could have made much more progress in reducing poverty, rather than just treading water.

Poverty rate, 1959–2013

| Actual poverty rate | |

|---|---|

| 1959-01-01 | 22.4% |

| 1960-01-01 | 22.2% |

| 1961-01-01 | 21.9% |

| 1962-01-01 | 21.0% |

| 1963-01-01 | 19.5% |

| 1964-01-01 | 19.0% |

| 1965-01-01 | 17.3% |

| 1966-01-01 | 14.7% |

| 1967-01-01 | 14.2% |

| 1968-01-01 | 12.8% |

| 1969-01-01 | 12.1% |

| 1970-01-01 | 12.6% |

| 1971-01-01 | 12.5% |

| 1972-01-01 | 11.9% |

| 1973-01-01 | 11.1% |

| 1974-01-01 | 11.2% |

| 1975-01-01 | 12.3% |

| 1976-01-01 | 11.8% |

| 1977-01-01 | 11.6% |

| 1978-01-01 | 11.4% |

| 1979-01-01 | 11.7% |

| 1980-01-01 | 13.0% |

| 1981-01-01 | 14.0% |

| 1982-01-01 | 15.0% |

| 1983-01-01 | 15.2% |

| 1984-01-01 | 14.4% |

| 1985-01-01 | 14.0% |

| 1986-01-01 | 13.6% |

| 1987-01-01 | 13.4% |

| 1988-01-01 | 13.0% |

| 1989-01-01 | 12.8% |

| 1990-01-01 | 13.5% |

| 1991-01-01 | 14.2% |

| 1992-01-01 | 14.8% |

| 1993-01-01 | 15.1% |

| 1994-01-01 | 14.5% |

| 1995-01-01 | 13.8% |

| 1996-01-01 | 13.7% |

| 1997-01-01 | 13.3% |

| 1998-01-01 | 12.7% |

| 1999-01-01 | 11.9% |

| 2000-01-01 | 11.3% |

| 2001-01-01 | 11.7% |

| 2002-01-01 | 12.1% |

| 2003-01-01 | 12.5% |

| 2004-01-01 | 12.7% |

| 2005-01-01 | 12.6% |

| 2006-01-01 | 12.3% |

| 2007-01-01 | 12.5% |

| 2008-01-01 | 13.2% |

| 2009-01-01 | 14.3% |

| 2010-01-01 | 15.1% |

| 2011-01-01 | 15.0% |

| 2012-01-01 | 15.0% |

| 2013-01-01 | 14.5% |

Source: EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement Historical Poverty Tables (Tables 2 and 4), Bureau of Economic Analysis National Income Product Accounts public data, and Danziger and Gottschalk (1995)

H-2B Wage Rule Loophole Lets Employers Exploit Migrant Workers

Last week the New York Times reported the latest innovation from employers who use the H-2B visa temporary foreign worker program to hire workers to staff traveling carnivals (think your local county or state fair): an employer-created union that collectively bargains with employers on behalf of workers to keep wages artificially low. Thanks to a loophole in H-2B wage regulations, low-wage, low-road employers are permitted to pay their temporary foreign workers dreadfully low wages.

The genesis of the prevailing wage loophole

For about half a decade, thanks to an H-2B wage regulation the George W. Bush administration illegally put in place in 2008, employers of landscapers, dishwashers, tree planters, maids, janitors, carnival workers, and construction workers were allowed to pay their H-2B employees as little as the local 17th percentile wage. (This is legally defined as the “Level 1” prevailing wage, based on Labor Department wage survey data for the job and local area.) After the rule was struck down in federal court in 2010, the Obama administration promulgated a final wage rule in 2011 that would have required employers to pay H-2B workers the local average wage (what’s also known as the Level 3 prevailing wage). However, this effort led to years of federal litigation brought by H-2B employers that stopped the rule in its tracks, and spurred an onslaught of corporate lobbying that convinced members of Congress from both major parties to deny funding to the Labor Department to enforce the rule.

Finally, in April 2013, the wage rule for the H-2B program was re-promulgated as an interim final rule issued jointly by the departments of Labor and Homeland Security. (The fact that the rule was issued jointly negated the main legal challenge, namely that the Labor Department lacked authority to promulgate any H-2B wage regulation.) The 2008 and 2013 H-2B wage rules both required employers to pay their H-2B employees the wage set out in an applicable collective bargaining agreement (CBA). But under the 2008 rule, if no CBA applied, then employers were allowed to pay the 17th percentile wage. The 2011 final H-2B wage rule that Congress blocked would have required employers to pay the higher wage between the CBA wage or the local average wage. Under the 2013 rule, if no CBA covered the H-2B worker, then the employer would have to pay the local average wage.

JOLTS Report is Evidence of an Economy Moving Sideways

Today’s Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) report corroborates last week’s jobs report, which continued to provide evidence that the economy is at best moving at a slow jog, with meager wage growth and employment growth that’s just keeping up with the growth in the working age population. The rate of job openings increased in July, while the hires rate fell and the quits rate remains depressed.

There continues to be a significant gap between the number of people looking for jobs and the number of job openings. The figure below illustrates the overall improvement in the economy over the last five years, as the unemployment level continues to fall and job openings rise. In a tighter economy (like the one shown in the initial year of data), these levels would be much closer together. So it’s clear that there is still a significant amount slack in the economy. Furthermore, on top of the 8+ million unemployed workers warming the bench, there are still more than three million workers sitting in the stands with little hope to even get in the game.

Job openings levels and unemployment levels, December 2000-July 2015

| Month | Job Openings level | Unemployment level |

|---|---|---|

| Dec-2000 | 4.934 | 5.634 |

| Jan-2001 | 5.273 | 6.023 |

| Feb-2001 | 4.706 | 6.089 |

| Mar-2001 | 4.618 | 6.141 |

| Apr-2001 | 4.668 | 6.271 |

| May-2001 | 4.444 | 6.226 |

| Jun-2001 | 4.232 | 6.484 |

| Jul-2001 | 4.354 | 6.583 |

| Aug-2001 | 4.095 | 7.042 |

| Sep-2001 | 3.973 | 7.142 |

| Oct-2001 | 3.594 | 7.694 |

| Nov-2001 | 3.545 | 8.003 |

| Dec-2001 | 3.586 | 8.258 |

| Jan-2002 | 3.587 | 8.182 |

| Feb-2002 | 3.412 | 8.215 |

| Mar-2002 | 3.605 | 8.304 |

| Apr-2002 | 3.357 | 8.599 |

| May-2002 | 3.525 | 8.399 |

| Jun-2002 | 3.325 | 8.393 |

| Jul-2002 | 3.343 | 8.39 |

| Aug-2002 | 3.462 | 8.304 |

| Sep-2002 | 3.319 | 8.251 |

| Oct-2002 | 3.502 | 8.307 |

| Nov-2002 | 3.585 | 8.52 |

| Dec-2002 | 3.074 | 8.64 |

| Jan-2003 | 3.686 | 8.52 |

| Feb-2003 | 3.402 | 8.618 |

| Mar-2003 | 3.101 | 8.588 |

| Apr-2003 | 3.182 | 8.842 |

| May-2003 | 3.201 | 8.957 |

| Jun-2003 | 3.356 | 9.266 |

| Jul-2003 | 3.195 | 9.011 |

| Aug-2003 | 3.239 | 8.896 |

| Sep-2003 | 3.054 | 8.921 |

| Oct-2003 | 3.196 | 8.732 |

| Nov-2003 | 3.316 | 8.576 |

| Dec-2003 | 3.334 | 8.317 |

| Jan-2004 | 3.391 | 8.37 |

| Feb-2004 | 3.437 | 8.167 |

| Mar-2004 | 3.42 | 8.491 |

| Apr-2004 | 3.466 | 8.17 |

| May-2004 | 3.658 | 8.212 |

| Jun-2004 | 3.384 | 8.286 |

| Jul-2004 | 3.835 | 8.136 |

| Aug-2004 | 3.578 | 7.99 |

| Sep-2004 | 3.704 | 7.927 |

| Oct-2004 | 3.779 | 8.061 |

| Nov-2004 | 3.456 | 7.932 |

| Dec-2004 | 3.846 | 7.934 |

| Jan-2005 | 3.595 | 7.784 |

| Feb-2005 | 3.842 | 7.98 |

| Mar-2005 | 3.891 | 7.737 |

| Apr-2005 | 4.115 | 7.672 |

| May-2005 | 3.824 | 7.651 |

| Jun-2005 | 4.018 | 7.524 |