No evidence of labor shortages but Congress considering giving H-2B employers access to more exploitable and underpaid guestworkers

Expanding and deregulating the H-2B visa program (a temporary foreign worker program that allows U.S. employers to hire low-wage guestworkers from abroad temporarily for seasonal, non-agricultural jobs, mostly in landscaping, forestry, seafood processing, and hospitality) has been a top goal for business groups including the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, ImmigrationWorks USA, landscaping and seafood employers, and the Essential Worker Immigration Coalition (EWIC)—lobbyists representing employers claiming they can’t find U.S. workers willing to mow lawns, plant trees, or pick crabmeat.

These lobbyists have never presented a credible case regarding labor shortages in H-2B jobs. But H-2B employers have spent millions of dollars on litigation, lobbying, and campaign contributions; anything it takes to keep wages from rising and to prevent their access to low-paid indentured foreign workers with few rights from ever being restricted.

And it’s happening again. To avoid a government shutdown, Congress has to pass appropriations legislation soon to fund the entire federal government. Whenever that happens, members of Congress attempt to insert “riders,” legislative provisions tucked into appropriations bills that amend the law in substantive ways that have nothing to do with appropriations. Thanks to the aforementioned corporate lobbyists, the current 2016 fiscal year appropriations negotiations have included discussions about riders to remake the H-2B program. The omnibus bill introduced in the House on the evening of December 15 included riders that would: 1) vastly increase the size of the H-2B program, 2) eliminate protections that keep workers from being idled without work or pay for long periods of time, and 3) prevent U.S. workers from having a fair shot at getting hired for job openings by preventing enforcement of the rules that require employers to recruit workers already present in the United States before they can hire an H-2B worker. Finally—and worst of all—if the House appropriations bill becomes law it will also dramatically lower the wage rates employers are required to pay, which would permit employers to pay their H-2B workers much less than American workers employed in the same jobs and local area. Needless to say, the lower wages H-2B workers will be paid create a huge incentive to hire temporary foreign workers instead of the local U.S. workers who reside in communities where the jobs are located.

In addition, legislation in the House and Senate has been introduced that would permanently implement these changes, including reducing H-2B wage rates, expanding the size of the H-2B program to about 200,000, and repealing all of the protections for foreign and American workers that the Obama administration just implemented in April 2015, after fighting opposition to them from corporate lobbyists and Congress for the past five years.

States and districts must fulfill the promise of more equity in education offered by new education law

For many of the nation’s schools, this week feels distinctly festive. Congress finally passed, and the President signed, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), reauthorizing the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), wrapping up a nearly eight year effort.

There’s much to celebrate in the new bill. First, no more No Child Left Behind, the 2001 iteration of ESEA that shifted our flagship federal education legislation from a civil rights law supporting the nation’s neediest schools and students to one that penalized those same schools for failing to meet higher standards, while withholding many of the supports they need to do so. Second, the newly reauthorized law returns key aspects of education policy to state and local authority, making it easier for schools to target interventions and resources based on their unique contexts. Third, by incorporating such strategies as pre-kindergarten and wraparound supports for disadvantaged students, it recognizes that students’ needs—and education itself—extend beyond K-12 and the school day.

At the same time, skeptics rightly point out that many of the states and localities celebrating their renewed authority have historically used that authority pretty badly. Under ESSA, state and local education agencies must practice due diligence and recognize that with increased flexibility and autonomy comes increased responsibility. The skeptics also point out that ESSA is still a far cry from what is needed to level the education playing field. Substantially improving education and narrowing gaps requires, at a minimum, funding levels that enable ESSA to serve as a real equalizer and implementation that extends that equalizing potential at the state and local levels.

Remarks by Josh Bivens on why it is too soon for the Fed to slow the economy

On Wednesday, December 16, the Federal Reserve is expected to announce that it is raising interest rates above zero for the first time in seven years. In recent briefings and presentations, EPI Research and Policy Director Josh Bivens has argued that a rate increase would be a mistake. The following is a rough transcript of remarks delivered at events including a December 1 briefing with Rep. John Conyers.

It’s a near lock that the Fed will raise the short-term interest rates it controls off of zero this week—where they’ve been sitting since the end of 2008. I think this is a mistake. You should raise interest rates only when you think you need to start slowing the pace of economic growth because you’re worried that fast growth and falling unemployment will spark too-rapid wage growth that will bleed into rapid price inflation. But there’s no reason to think that the pace of economic growth today is excessive and needs to be slowed because of incipient inflation.1

And the stakes to getting this tradeoff between low unemployment and stable inflation wrong are huge. Since 1979, the bottom 70 percent of American workers have essentially seen one multi-year episode of strong, equitable growth in hourly pay. That occurred in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when unemployment fell far below what existing estimates said it could without sparking inflation—it bottomed out at 3.8 percent for a month in 2000, and averaged 4.1 percent for two solid years in 1999 and 2000. This led to the only serious period of strong, equitable wage growth in the past 35 years. The bottom 70 percent saw trivial wage growth (or wage declines) in the entire rest of that period. The figure below shows wage growth in the late 1990s/early 2000s compared to the rest of the 1979-2013 period for various points in the wage distribution. Besides the top 5 percent, it can be seen that most wages grew much faster during the late 1990s high-pressure labor markets than in other periods post-1979.

Republicans and some Democrats defend financial advice that’s not worth getting

What if the next time you went for a medical checkup, you were accosted by a pharmaceutical rep waiting for her expense-account lunch with the doctor. But instead of saving her pitch for the doctor—a sleazy enough practice—the drug rep began telling everyone in the room that they should take an expensive drug that has no advantage over a generic version and is approved only for medical conditions no one there has.

Illegal? Yes. But imagine that this was actually legal and that President Obama, with the support of progressives in his party, had issued a proposed rule intended to curb such practices by requiring that anyone offering advice to patients in a doctor’s office have the patient’s best interest at heart.

Here’s what would happen: Republicans in Congress would start parroting industry talking points about this having a chilling effect on urgently-needed advice people are receiving for free and can’t afford to pay for. A substantial minority of congressional Democrats would claim to agree with the president in principle, but find one reason or another to delay the rule indefinitely with quibbles and questions. The industry lobby would continue to shower Republicans with campaign donations, while the hand-wringing Democrats would avoid being singled out by the industry in their quest for reelection. Pundits would treat it as a complicated issue where there is serious risk of unintended consequences, and Americans would continue to be suckered into paying exorbitant prices for risky products they shouldn’t be buying in the first place.

The labor market still recovering: We should let it

The Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) report released today by the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows signs of a continued slow recovery. Job openings fell slightly to 5.4 million, and the quits rate remained, stubbornly, at 1.9 percent, where it has been for most of the last year. Along with last Friday’s jobs report, today’s report provides more evidence of a recovering but still weak economy. While most indicators have been trending in the right direction, nominal wage growth and the prime-age employment-to-population ratio remain far outside of target ranges, and provide ample evidence that the economy has a way to go before reaching full employment.

In October, there were 1.5 unemployed workers for every job opening, a slight tick up from last month. That means they for every 15 jobs, there are five potential workers who won’t be able to find a job no matter how hard they look. And the job-seekers-to-job-openings ratio is higher among certain sectors. Notably, there are still 45 unemployed construction workers for every 10 job openings in construction.

The sluggish quits rate is particularly troubling. At 1.9 percent, the quits rate was still 9.2 percent lower than it was in 2007, before the recession began. This is evidence that workers are stuck in jobs that they would leave if they could. A larger number of people voluntarily quitting their jobs would indicate a strong labor market—one in which workers are able to leave jobs that are not right for them and find new ones. Hopefully we will see a return to pre-recession levels of voluntary quits, but given that the rate has stayed flat, we are obviously not there yet.

December Interest Rate Increase: Will the Fed Raise Rates vs. Should It

This piece originally appeared in the Wall Street Journal’s Think Tank blog.

Our friend and former colleague Jared Bernstein has mounted a small but strategic retreat in the campaign to have the Fed continue focusing on full employment. He has written that Friday’s jobs report, though not stellar, was good enough to make a December increase in interest rates a near-certainty. He then argues that this might not be the worst thing in the world:

Even while I do not see much rationale for an increase, especially given elevated underemployment and the stark lack of inflationary pressures, given their recent messaging, a non-liftoff in December would suggest the economy is a lot worse than they thought in some secret way they’ve been keeping from us. Such a negative surprise would be ill-advised.

Presuming that they won’t want to go there, it’s now all about the ‘path to normalization:’ how fast they raise. … [I]f I’m Chair Yellen, my message to the hawks is: ‘OK, you got your rate liftoff even though the data weren’t really there for it. Now back…off and let’s go back to being data-driven about future increases.’ ”

Jared is right that the larger economic question is not just about a 25-basis-point increase this month but about how rapidly interest rates climb over the next year or so. But we’re still really uncomfortable with starting lift-off before the data support it. Once you start indulging faith-based arguments about monetary policy, you’ve lowered the bar for data-driven analysis, making smart policy choices harder and harder to sustain.

What to watch on Jobs Day: The call for a rate increase is not backed up by wage data

On Friday, the Bureau of Labor Statistics will release the November numbers on the state of the labor market. On December 15, the Federal Open Market Committee will meet to determine whether they should raise interest rates, and most prognosticators think that this time they will actually go through with it. Last month’s stronger than expected jobs report led many to declare, prematurely, that it is time to start raising rates in order to ward off incipient inflation. The reality is that we need to see strong wage growth that is consistent and strong enough so that labor share of income returns to pre-recession levels and the labor market achieves a full recovery. Then, and only then, should we begin a conversation about raising rates.

Over the last six years, nominal wage growth has continued hover around 2.0 to 2.2 percent, far below target (see below on the target). Yes, October’s year-over-year growth was stronger—2.5 percent for nonfarm employees, although it was lower for production and nonsupervisory workers (2.2 percent). But again, one month of data is not sufficient evidence, and even 2.5 percent is still far below the wage target.

The Department of Homeland Security’s proposed STEM OPT extension fails to protect foreign students and American workers

For decades, the Optional Practical Training (OPT) program has permitted foreign graduates of U.S. universities, who visit the United States to study through the F-1 nonimmigrant visa program, to be employed in the United States for up to 12 months immediately after graduation. In 2008, the George W. Bush administration extended the OPT program period to 29 months for F-1 graduates of a science, technology, engineering, or math (STEM) program—known as the STEM OPT extension—through an Interim Final Rule (IFR) promulgated by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). On August 12, 2015, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia struck down the 2008 IFR, ruling that the regulation was illegally created in violation of the Administrative Procedure Act. Judge Ellen Segal Huvelle vacated the IFR effective February 12, 2016.

On October 19, 2015, President Obama proposed new DHS regulations that would reinstate the STEM OPT extension and increase its duration from 29 months to 36 months per STEM degree for foreign STEM graduates, and allow the extension eligibility to apply to up to two STEM degrees. Effectively, this would allow foreign graduates with STEM degrees to be employed for up to six years while on an F-1 visa. The DHS regulatory notice solicited comments from the public. In our comment, we argue that the president’s STEM OPT extension proposal is problematic for several reasons:

Closing loopholes in Buy American Act could create up to 100,000 U.S. jobs

By closing loopholes in the Buy American Act, the 21st Century Buy American Act will increase demand for U.S. manufactured goods and create at least 60,000 to 100,000 U.S. jobs. The Buy American Act requires “substantially all” direct purchases by the federal government (of more than $3,000) “be attributable to American-made components.” However, there are a number of exclusions or loopholes in the Buy American Act. The single largest is an exception for “goods that are to be used outside of the country,” and the 21st Century Buy American Act includes provisions to close it. In addition, current regulations interpreting the Buy American Act state that “at least 50 percent of the cost must be attributable to American content,” which can reduce net demand for American made content.

Between 2010 and 2015, the “goods used outside of the country exception” was used to purchase $42.3 billion in goods that were manufactured outside of the United States, an average of $8.5 billion per year.1 The 21st Century Buy American Act would require most or all of those goods to be U.S. made, increasing demand for U.S. manufactured goods by up to $8.5 billion per year.2 Although labor markets have improved in the United States since the recession, there remains substantial slack and 2.6 million jobs were still needed to catch up with growth in the potential labor force in September 2015. I assume, based on recent research by my colleague Josh Bivens (Table 5) that wages earned by new manufacturing workers will support a macroeconomic multiplier of 1.6 in the domestic economy over the next year.3 I also assume, based on total GDP and employment levels in 2014 that a 1 percent increase in GDP adds 1.3 million jobs to the economy. Thus, the $8.5 billion increase in spending on domestic manufactured goods (with 100 percent domestic content) would increase GDP by $13.6 billion (0.08 percent), creating up to 100,000 new jobs in the domestic economy.

Remarks by Congresswoman Rosa DeLauro at the unveiling of EPI’s Women’s Economic Agenda

Congresswoman Rosa DeLauro (D-Conn.) spoke at the unveiling of EPI’s Women’s Economic Agenda on November 18, 2015. Her remarks, as prepared for delivery, are posted below.

Good morning. Maya, thank you for that kind introduction. I have to first recognize EPI and Larry who have been a godsend in providing members of Congress great economic information that focuses on the impacts of public policies on low and middle class Americans and their families. The topics they cover are wide-ranging—from the impact of various trade agreements to the current jobs crises, where people are in jobs that don’t pay them enough to live on.

Let me also acknowledge my colleagues and the advocates who join me at the podium. Senator Warren—a woman who needs no introduction. The Boston Globe describes her as “a fierce advocate for the lot of working families.” Senator Warren has a reputation for knowing how to get things done.

Elise Gould at EPI—thank you for your tireless work on this Women’s Economic Agenda. Let me acknowledge Liz Shuler. Thank you for your leadership and advocacy at AFL-CIO. And all the advocates here today. Each of them put working families at the heart of everything they do.

Today we come together to push the policies as part of the Economic Policy Institute’s Women’s Economic Agenda to improve the lives of working women and families.

Reauthorizing ESEA: a first step in returning education to its roots

The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) appears, finally, to be nearing reauthorization. Barring unforeseen circumstances, Congress will, after years of effort, begin to right some of the wrongs wrought by the excessive focus on standards and accountability in No Child Left Behind (ESEA’s current iteration). The draft framework sent to the conference committee swings the pendulum from federal overreach and prescription back toward state and local control. It claws back—but does not eliminate—accountability requirements by striking “Adequate Yearly Progress,” annual measurable objectives, and the unattainable goal of 100% proficiency from the act.

Not only would this ESEA do less wrong, it would do more right; key passages hold promise to return ESEA to its civil rights and antipoverty roots. Informed by rising rates of student poverty, the proposed framework recognizes that poverty poses a major impediment to effective teaching and learning.

It is true that much of the debate around reauthorization has been about testing, funding for charter schools and vouchers, the Common Core State Standards, and a range of other issues worthy of consideration. But these are not central to the core purpose of ESEA, which was originally passed as part of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. Over the years, that purpose has been diluted. But as 10 organizations, led by the Broader, Bolder Approach to Education, wrote to education leaders of both houses last year, Congress has a unique chance to reverse course and bring ESEA back to its roots. We called on Congress to follow five key principles in ESEA reauthorization:

These five principles represent the original spirit and intent of the law, and they give states, districts, and schools the flexibility they need to address their specific concerns and meet the unique needs of their students. We propose that they be at the center of a reauthorized Elementary and Secondary Education Act.

Closing the pay gap and beyond: A brief explanation of the motivation behind EPI’s Women’s Economic Agenda

This morning, EPI released our Women’s Economic Agenda (and an accompanying research paper)—a set of policies designed to close the gender wage gap and ensure that women achieve real, lasting economic security.

In the last several decades women have made great strides in educational attainment and labor force participation. Nevertheless, when compared with men, women are still paid less, are more likely to hold low-wage jobs, and are more likely to live in poverty. And the problem is worse for women of color. As demonstrated in numerous research studies, gender wage disparities are present across the wage distribution and within education, occupations, and sectors, sometimes to a grave degree.

Closing the gender wage gap is absolutely essential to helping women achieve economic security. But to bring genuine economic success to American women and their families, we must do more. The gender wage gap is only one way the economy shortchanges women.

At the same time the gender wage gap has persisted, hourly wages for the vast majority of workers have stagnated, as the fruits of increased productivity and a growing economy have accrued to those at the top. It hasn’t always been this way. As you can see in the figure below, pay rose with productivity in the three decades following World War II. But since the 1970s, pay and productivity have grown further apart, as the result of intentional policy decisions that eroded the leverage of the vast majority of workers to secure higher wages.

A progressive women’s economic agenda, one that seeks to truly maximize women’s economic potential, must focus on both closing the gender wage gap and raising wages more generally.

Bad tax or no tax? The ACA excise tax debate, continued

Friend and former colleague Jared Bernstein made a defense of the ACA excise tax on expensive employer-provided health insurance plans a couple of days ago. It’s about as good a defense as there is of the excise tax, but at EPI we’re still largely unconvinced. He provides some arguments on the substance of the tax (which I’ll briefly touch on below), but mostly leans on a political argument, that this is a tax that actually exists, and given the anti-tax zealotry of congressional Republicans, we should be very leery of giving away any revenue that is currently on the books.

First, some economics, and then on to some politics.

Jared and I are roughly on the same page regarding the wage/health care trade off issue. As the excise tax is imposed on plan costs above a certain threshold, this will encourage people to shift into plans with lower upfront premiums. But these lower upfront premiums mean that more health costs are shifted onto households in the form of higher co-pays, deductibles, and co-insurance. The good news of lower premiums, however, is that this frees up money for employers to give more compensation to workers in the form of cash wages rather than health premiums. Elise Gould and I have argued in the past that this wage boost stemming from less-generous health plans is likely to be a long time coming, particularly if labor markets remain slack. Jared agrees. He argues this trade off likely will happen in the longer run. I agree (though I’m not 100 percent sure, and am troubled by the lack of robust empirical support in the research literature on this). My beef has mostly been with people who simply state that the excise tax will lead to a “raise” for American workers. That’s bunk. It will change the composition, not the level, of employee compensation. And it will increase total taxes on this compensation, hence cutting their take-home pay.

Hiring lags as economy slows over the summer

Today’s release of the September Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) data corroborates the story we saw in August and September’s jobs reports, as hiring slowed and the economy added a paltry number of jobs (note that the JOLTS data comes with a one-month lag relative to monthly jobs numbers, so the much-improved October jobs report data is not reflected in today’s release). Although the number of job openings increased to 5.5 million in September, this was after a large decrease to from 5.7 to 5.4 million in August. But the main data point we should focus on is the hires rate, which actually fell in September from 3.6 percent to 3.5 percent, the lowest it has been in a year.

In September, there were 1.4 active job seekers for every job opening. Although this decline is a welcome improvement in the JOLTS ratio, it is important to remember that there are still almost 8 million unemployed workers and over 3.5 million estimated “missing workers” who have left the labor force altogether because job opportunities have been so weak.

In fact, there is still a significant gap between the number of people looking for jobs and the number of job openings. The figure below shows the levels of unemployed workers and job openings. You can see the labor market improve over the last five years, as the number of unemployed workers falls and job openings rise. In a stronger economy (like the one shown in the initial year of data), these levels would be much closer together.

The National Association of Home Builders’ evidence supports DOL’s proposed rule on overtime

The National Association of Homebuilders (NAHB), both in congressional testimony and in the official comments it submitted to the Department of Labor, makes a strong case for the Obama administration’s proposed rule on the overtime rights of salaried workers. Yes, you read that right: NAHB makes an ironclad case that businesses will have little difficulty adjusting to the proposed rule change.

Naturally, NAHB, which claims to represent 140,000 members involved in “home building, remodeling, multifamily construction, property management, subcontracting, design, housing finance, building product manufacturing and other aspects of residential and light commercial construction,” testified before Congress that the DOL proposal would be the end of Western Civilization. But the data they presented tell a different story.

NAHB’s own survey of its members found that two-thirds would make no changes in their policies or operations. Many, of course, already pay their supervisors more than $50,440 a year and would be unaffected. Of the one-third that would make adjustments, most would do exactly what the rule contemplates: they would reduce the amount of overtime their supervisors work. Twice as many firms would raise the salary of their supervisors above the $50,440 threshold as would reduce their salary. And only 13 percent of the firms that said they would make a change would switch their supervisors from salary to hourly wage. In other words, just 4 percent of home builders would convert their salaried supervisors to hourly pay.

It is noteworthy that of the four top responses among the home builders who say they will make changes, two are undeniably positive—raising salaries and reducing overtime hours worked. Apparently, Ed Brady, the NAHB official who testified in the Small Business committee, is one of the few home builders in America who would contemplate outsourcing the role of construction supervisor in order to avoid paying overtime. Any contractor who employed that supervisor would have to deal with the same issues as Mr. Brady, and would charge for the costs they entail, plus a profit— so perhaps it’s not surprising that Mr. Brady is alone in planning to outsource his supervisors.

Clearly, the NAHB’s own evidence shows that DOL’s proposed changes in the overtime rules will have small, mostly positive effects on the homebuilding industry and its employees.

Looking beyond the topline employment number: Public-sector jobs remain depressed

An increase of 271,000 in payroll employment is a promising sign. One month is surely not predictive of the future, but if this continues, it is good news for the economy and the people in it. While the topline employment number for October is quite encouraging, other indicators continue to paint a picture of a plateaued economy, particularly the fact that there has been no growth in prime-age employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) this year.

The share of the 25–54 year old population actually employed is arguably one of the best measures of economic health. At 77.2 percent, it remains depressed— lower than the worst of the prior two recessions before the Great Recession. The effects of such low prime-age EPOPs may be far-reaching, affecting not only the incomes but also the health of the population.

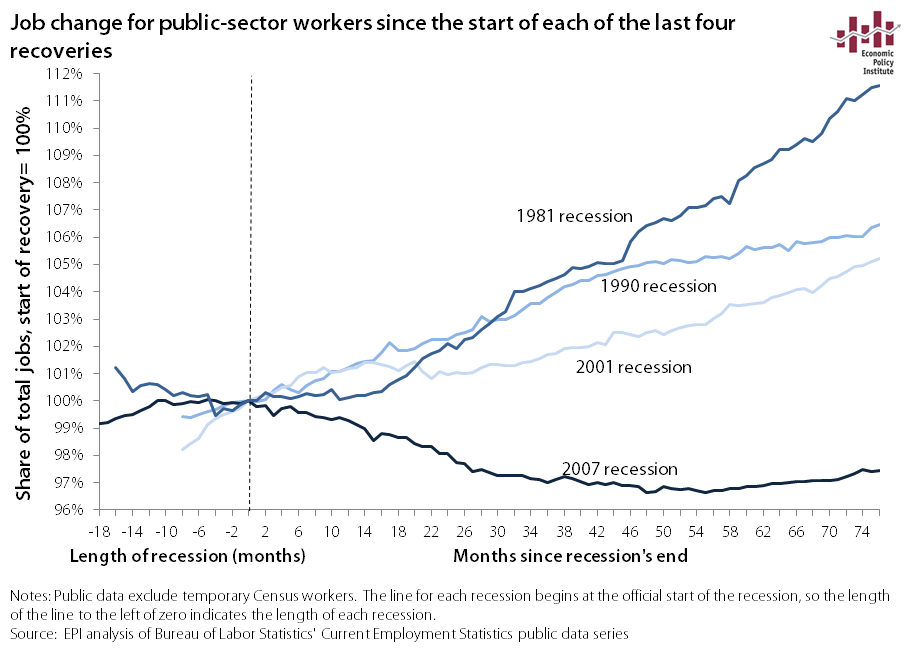

Public-sector employment also remains weak, and depressed government spending continues to be the leading cause of the sluggish pace of recovery in recent years. One thing that has been historically unique about this recovery is the unprecedented loss of and lack of recovery of public-sector jobs. The figure below compares public-sector employment in this recovery to the three prior recoveries. Recessions are marked by the lines to the left of the zero point on the x-axis, while recoveries are to the right. This graph clearly shows that the public sector has seen massive job loss in the current recovery. This is a direct result of austerity policy and a huge drag that has not weighed on earlier recoveries.

Where can we find hope for our schools?

Bringing It Back Home, a report issued by the Economic Policy Institute at the end of October, provides a distinct service in reminding Americans that they can learn more about how to improve their schools by looking at successful American states than they can by heading overseas to pry lessons out of foreigners.

The authors, Stanford’s Martin Carnoy, EPI’s Emma Garcia, and Tatiana Khavenson at the National Research University Higher School of Economics in Moscow, have produced an impressive piece of scholarship. Their work makes a genuine new contribution to the discussion about how to improve American schools.

In considering this study, several points need to be born in mind.

First, the United States has very real problems in its schools. We cannot be Pollyannas about where we are. Average student performance is not where we would like it to be, and the average conceals terrible gaps between students doing well and those bringing up in the rear.

Historically, we have done a reasonably good job with the traditional students our schools were designed to serve. But now we face a new challenge: a student population in which the majority of students are, for the first time in our history, both low-income and children of color.

What to watch on Jobs Day: Job growth has only been fast enough to keep up with population growth

On Friday, the Bureau of Labor Statistics will release the October numbers on the state of the labor market. As usual, I will be looking closely at nominal wage growth. Wage growth—a key indicator of labor market slack—remains far below target levels. It’s important to continue to encourage the Federal Reserve to keep their foot off the brakes until wage growth picks up. But, right now, I want to talk about the pace of job growth.

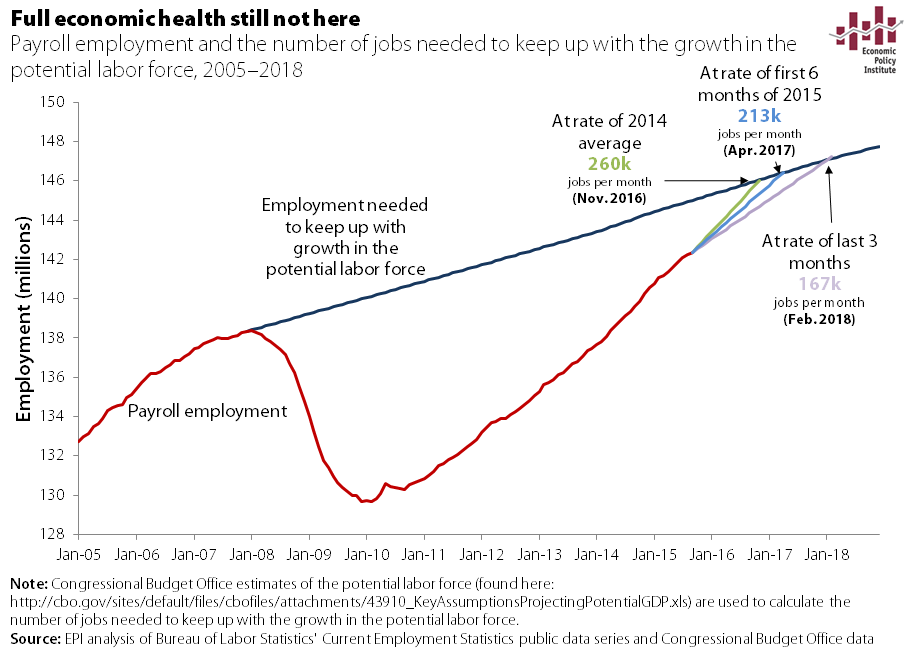

Previously, I’ve written about how payroll employment has been slower in 2015 compared with 2014. Average monthly job gains were 260,000 in 2014. This year so far job growth has averaged only 198,000— and moreover, job growth the last three months was noticeably slower than the previous three months. In the third quarter, average job gains were 167,000, compared with an average of 231,000 in the second quarter.

So, job growth has slowed, but what do these numbers really mean? Recent months are clearly weaker, slower, more sluggish than previous months, but are we still on the right track? At this recent slower rate of growth, a full jobs recovery is still almost two and a half years away.

Brookings paper on the Postal Service gets the facts wrong

Elaine Kamarck’s essay, “Delaying the Inevitable: Political Stalemate and the U.S. Postal Service,” grossly misstates the facts about the central cause of the Postal Service’s financial crisis, which is the statutory requirement to pre‐fund retiree health benefits. Current law, enacted in 2006, requires the Postal Service to pre‐fund these benefits over a 10‐year period at a cost of $5.5 billion per year. Kamarck writes (citing a Report by the Postal Regulatory Commission1) that retiree health benefits caused “$22,417 million in expenses out of a total net loss of $5.5 billion in fiscal year 2014.” Wrong. The $22.4 billion figure Kamarck cites represents the liability the Postal Service accrued over a 10‐year period due to its inability to make all the pre‐funding payments mandated by the 2006 law.

Kamarck misses what the Postal Regulatory Commission Report clearly shows: The $5.7 billion pre‐funding expense for 2014 exceeded the Postal Service’s $5.5 billion net loss for the year. For 2014 operations, the Postal Service had a positive net income of nearly $1.4 billion. (The Postal Service also had a positive net income based on operations in 2013 and in the first half of fiscal year 2015.)

Unfortunately, that’s not all she got wrong. For example, Kamarck pegs her analysis to the “dramatic decline in the volume of single piece first class mail,” citing a study by the USPS Office of Inspector General (OIG).2 But in doing so, she omits reference to the several important qualifiers in that OIG study. First, as the OIG study states, “The total volume decline figure hides significant differences in mail volume by geographical area. Differences in mail use such as these have important policy implications for the nation and for the Postal Service.”3 In some parts of the country, there has been little or no decline in the use of First Class Mail;4 and even in areas of high volume loss, significant volumes of First Class Mail remain.5

Wages for top earners soared in 2014: Fly top 0.1 percent, fly

After dipping slightly in 2013, annual earnings of the top 1.0 percent of wages earners grew 4.9 percent in 2014, and the top 0.1 percent’s earnings grew 8.9 percent, according to our analysis of the latest Social Security Administration wage data. This analysis provides the first look at the likely trend of the household incomes of the top 1.0 percent. The top 1.0 percent’s earnings have nearly returned to their previous high point, attained in 2007. In fact, the earnings of workers between the 99th and 99.9th percentiles have reached their highest level of all time—it’s only the earnings of the top 0.1 percent that are still below 2007 levels. The top 5.0 percent has also reached its highest level of earnings ever.

Surprisingly, wages of the top 1.0 percent declined in 2013, while those of the bottom 99.0 percent grew. We hypothesized that this decline in top earnings might reflect income shifting, as a new, higher top bracket—39.6 percent—and an additional 0.9 percent Medicare tax on high earners provided incentives to shift compensation into 2012 (when top 1.0 percent wages grew 6.1 percent). It looks like we were right. The strong growth of earnings at the top in 2014 suggests that the highest earners have found their mojo once again. In the analysis below we review these recent trends, as well as trends during the Great Recession and over the longer-term.

Wage growth from 2013 to 2014

The table below shows that annual earnings for the bottom 90 percent of earners rose 1.4 percent in 2014, to $33,297—just $20 above their 2007 level. Given that hourly wages were stagnant or falling throughout the wage scale in 2014, this growth in annual wages must have been due to an increase in hours worked per worker. Workers between the 90th and 95th percentiles of wages (averaging about $110,000 in 2014) saw wage growth comparable to that of the bottom 90 percent (1.3 percent) and the earnings of workers between the 95th and 99th percentile grew 1.9 percent. Among the 1.0 percent, earnings for the top 0.1 percent grew the strongest (8.9 percent), while those just beneath them—the next 0.9 percent—had a slower 2.6 percent earnings growth.

Forced binding arbitration robs workers and consumers of basic rights

The New York Times has published two parts of a three-part series about the epidemic of arbitration clauses that have cropped up in millions of transactions between corporations and their customers and employees. The clauses are routinely included in employment contracts, cell-phone contracts, consumer product purchase agreements, cable subscriptions, rental agreements, and a multitude of financial transactions, as a way to prevent injured parties from having their day in court. Giving up the constitutionally protected right to sue in state or federal court is a big deal and is often the result of ignorance and deceit: millions of people have no idea the clauses are there in the fine print of contract provisions written in legalese that few individuals ever read or comprehend. They don’t find out they’ve lost their rights until they need them.

Individuals give up not just their right to go to court but all protections regarding the venue of any hearing their claim will receive (for example, the agreement might require arbitration in a city a thousand miles away). They might give up certain remedies and the right to appeal even if the arbitrator gets the law completely wrong, and give up the essential right to join with other victims to file a class action, especially important when each claim is small and no single individual could rationally pay to hire a lawyer and bring a lawsuit for such a small sum.

Disappointing NAEP scores and the questions they raise

This week we learned that, for the first time in its 20 year history, scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) declined or were stagnant in both fourth and eighth grades in both math and reading. Naturally, this is prompting concern and questions. Are current education policies on the right course? Is the Common Core not working? Do these scores indicate “test fatigue” because kids are taking too many tests?

These questions cannot be answered by two years of data, even relatively reliable data like NAEP scores. We should be looking at longer-term trends—this decline may be a blip, even if it was across-the-board. We also need to disaggregate the data and look at not just how the average student performed, http://www.canadianpharmacy365.net/. Perhaps most important, we should always consider these data in a broader context.

Looking at this year’s scores as part of a longer term trend, we see that the past decade (post-No Child Left Behind) delivered much smaller gains than the years prior. Fourth graders gained substantially more in math between 1992 and 2003 (15 points) than in the twelve years since (nine points between 2003 and this year’s 2015 results). In eighth grade, the difference is even more striking—a gain of 15 points from 1992–2003, versus just four since. And while overall gains in reading have been much smaller, the ratio is similar—fourth graders gained five points from 1992–2003, but just one point in the past twelve years.

Disney H-1B Scandal in Spotlight Again: Meet The American Workers Whose Jobs and Careers Were Destroyed by the H-1B Program

Two courageous Disney workers were interviewed yesterday on a local television news program in Sarasota, Florida. In the interview, they describe what it was like to train their foreign replacements: “Like when a guillotine falls down on you.” It’s hard to overestimate how many Americans’ livelihoods have been damaged by the H-1B visa guestworker program, which allows employers to hire about 130,000 new college-educated foreign workers every year for up to six years at a time.

Does the budget deal include benefit cuts?

Many of us reacted to the tentative budget deal with surprised relief. Assuming the agreement holds, the White House was able to lift the debt ceiling and end the sequester without losing limbs in the process, as my colleague Ross Eisenbrey aptly put it. This time the administration resisted the urge to throw red meat to the other side’s lions.

Inevitably, the deal will intensify dissent on the right. But there is also a surprisingly heated debate about the seemingly benign Social Security provisions among advocates, some of whom view any cost savings as benefit cuts and say an off-budget program with a dedicated funding stream should not be discussed in budget negotiations (though they don’t object to including transfers to the disability program in this budget deal). In particular, a vocal minority opposes a provision that would no longer allow people to take advantage of the “file and suspend” strategy, whereby someone eligible for both retirement and spousal benefits delays take-up of the former to receive a larger benefit at age 70, while receiving the latter in the interim (most people without clever financial advisers simply receive the higher of the two benefits whenever they apply).

Eliminating “aggressive Social Security-claiming strategies, which allow upper-income beneficiaries to manipulate the timing of collection of Social Security benefits in order to maximize delayed retirement credits” was something the president included in his fiscal-year 2015 budget, not something the administration reluctantly agreed to. And most advocates, http://www.canadianpharmacy365.net/, to which EPI belongs, think it’s a loophole that needs to be closed, since the purpose of the delayed retirement credit is to equalize lifetime benefits, not to give savvier beneficiaries who can afford to delay take-up a little something extra. The dissidents counter that a benefit cut by any other name is still a benefit cut, and say it’s a strategy that can help divorced women, who can be particularly vulnerable in retirement.

The dissidents make a strong case with feminist appeal. But it’s still double dipping even if a few people who take advantage actually need a larger benefit. In the end, it all seems a distraction from the benefits of the agreement, which include averting large benefit cuts to disabled beneficiaries.

The Republican Study Committee wants to ratchet austerity up well past the sequester

A bit over four years ago, the U.S. economy threatened to breach the legislated (and totally arbitrary) national debt ceiling. There was no economic sign (high interest rates, for example) that argued that public debt was too high, and there were many economic signs that such debt was actually too low. Yet because of a quirk in American economic policy, Congress must periodically act to raise the nominal value of the debt allowed to be issue by the federal government. This is normally a pro forma vote, at least after members of Congress are allowed to rail against what they see as the fiscal policy failings of the current president.

But in August 2011, in an unprecedented breach of Congressional norms, Republicans in Congress instead used the looming breach of the debt ceiling to demand spending cuts. Besides breaching legislative norms, the resulting cuts were also economically disastrous. The Budget Control Act (BCA) of 2011 and the resulting spending austerity (often short-handed not quite accurately as “the sequester”) fully explains why the U.S. economy has yet to reach a full recovery from the Great Recession, even more than six years after the recession officially ended. If we had instead simply followed the average path of federal spending that characterized all previous post-World War II recessions, the U.S. economy would be at full employment by now, and the Fed would have certainly begun raising interest rates a long time ago.

The fiscal drag resulting from the sequester relented a little in the past two years, as the result of a compromise reached between the House and Senate budget committees. But this compromise only rolled back sequester cuts for two years. For fiscal year 2016, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that not extending this compromise and instead returning to 2011 BCA spending targets could cost as many as 800,000 jobs as these cuts drag on aggregate demand.

Pennsylvania’s upcoming budget decision highlights the choice facing states across the country

Over the past few years, many states have faced critical choices about whether to raise state revenues, hold firm to existing—potentially inadequate—tax structures, or cut taxes, sometimes on top of cuts made in earlier years. Today, lawmakers in Pennsylvania are again considering these same choices, but with a somewhat unique opportunity to change course from the path they took earlier in the recovery. Two weeks ago, Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf released a plan to raise revenue which, he stressed in a press conference, will begin to address the state’s structural budget deficit and reverse deep cuts to education spending that occurred in 2010-11.

As lawmakers throughout the country consider plans for the coming fiscal year, it is instructive to compare the fiscal and economic performance of Pennsylvania in recent years with other states that made either similar or starkly different fiscal choices. For example, California and Minnesota raised taxes to improve their fiscal health and to reinvest in education, while Kansas and Wisconsin followed the same path as Pennsylvania—reducing taxes by varying degrees and dramatically cutting education spending.

The results of this policy experiment can be summarized as follows:

- The two states that raised revenues have enjoyed percent job growth since 2010-11 that is one-and-a-half to three times larger than the three states that cut taxes.

- The states that increased taxes have seen revenue growth—both as a result of the tax changes and as a result of stronger recoveries—of 8 percent and 15 percent. Kansas has seen its revenues fall 5 percent and Pennsylvania and Wisconsin have seen revenue growth of 5 percent and 7 percent, meager enough to make fiscal stability and reinvestment in vital programs difficult.

- State school funding per pupil has increased 15-21 percent in Minnesota and California while plunging 9-14 percent in the three tax-cut states. That means the ratio of funding per pupil in Minnesota and California compared to any of the other three states has shifted 26-41 percent in just four years.

More of the same: JOLTS is continued evidence of a slow moving economy

Today’s Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) report shows there has been little change in the labor market for America’s workers. The rate of job openings actually decreased in August to 5.4 million. At the same time, the hires rate held steady while the quits rate remains depressed. Coupled with jobs reports so far this year, today’s report provides more evidence of a slow moving economy, with meager wage growth and employment growth that’s just keeping up with the growth in the working age population.

There is still a significant gap between the number of people looking for jobs and the number of job openings. The figure below shows the levels of unemployed workers and job openings. You can see the labor market improve over the last five years, as the number of unemployed workers falls and job openings rise. In a stronger economy (like the one shown in the initial year of data), these levels would be much closer together. Today, there are still 1.5 active job seekers for every job opening. Furthermore, on top of the 8+ million unemployed workers warming the bench, there are still four million workers sitting in the stands with little hope to even get in the game.

Job openings levels and unemployment levels, 2000-2015

| Month | Job Openings level | Unemployment level |

|---|---|---|

| Dec-2000 | 4.934 | 5.634 |

| Jan-2001 | 5.273 | 6.023 |

| Feb-2001 | 4.706 | 6.089 |

| Mar-2001 | 4.618 | 6.141 |

| Apr-2001 | 4.668 | 6.271 |

| May-2001 | 4.444 | 6.226 |

| Jun-2001 | 4.232 | 6.484 |

| Jul-2001 | 4.354 | 6.583 |

| Aug-2001 | 4.095 | 7.042 |

| Sep-2001 | 3.973 | 7.142 |

| Oct-2001 | 3.594 | 7.694 |

| Nov-2001 | 3.545 | 8.003 |

| Dec-2001 | 3.586 | 8.258 |

| Jan-2002 | 3.587 | 8.182 |

| Feb-2002 | 3.412 | 8.215 |

| Mar-2002 | 3.605 | 8.304 |

| Apr-2002 | 3.357 | 8.599 |

| May-2002 | 3.525 | 8.399 |

| Jun-2002 | 3.325 | 8.393 |

| Jul-2002 | 3.343 | 8.39 |

| Aug-2002 | 3.462 | 8.304 |

| Sep-2002 | 3.319 | 8.251 |

| Oct-2002 | 3.502 | 8.307 |

| Nov-2002 | 3.585 | 8.52 |

| Dec-2002 | 3.074 | 8.64 |

| Jan-2003 | 3.686 | 8.52 |

| Feb-2003 | 3.402 | 8.618 |

| Mar-2003 | 3.101 | 8.588 |

| Apr-2003 | 3.182 | 8.842 |

| May-2003 | 3.201 | 8.957 |

| Jun-2003 | 3.356 | 9.266 |

| Jul-2003 | 3.195 | 9.011 |

| Aug-2003 | 3.239 | 8.896 |

| Sep-2003 | 3.054 | 8.921 |

| Oct-2003 | 3.196 | 8.732 |

| Nov-2003 | 3.316 | 8.576 |

| Dec-2003 | 3.334 | 8.317 |

| Jan-2004 | 3.391 | 8.37 |

| Feb-2004 | 3.437 | 8.167 |

| Mar-2004 | 3.42 | 8.491 |

| Apr-2004 | 3.466 | 8.17 |

| May-2004 | 3.658 | 8.212 |

| Jun-2004 | 3.384 | 8.286 |

| Jul-2004 | 3.835 | 8.136 |

| Aug-2004 | 3.578 | 7.99 |

| Sep-2004 | 3.704 | 7.927 |

| Oct-2004 | 3.779 | 8.061 |

| Nov-2004 | 3.456 | 7.932 |

| Dec-2004 | 3.846 | 7.934 |

| Jan-2005 | 3.595 | 7.784 |

| Feb-2005 | 3.842 | 7.98 |

| Mar-2005 | 3.891 | 7.737 |

| Apr-2005 | 4.115 | 7.672 |

| May-2005 | 3.824 | 7.651 |

| Jun-2005 | 4.018 | 7.524 |

| Jul-2005 | 4.162 | 7.406 |

| Aug-2005 | 4.085 | 7.345 |

| Sep-2005 | 4.227 | 7.553 |

| Oct-2005 | 4.23 | 7.453 |

| Nov-2005 | 4.341 | 7.566 |

| Dec-2005 | 4.249 | 7.279 |

| Jan-2006 | 4.278 | 7.064 |

| Feb-2006 | 4.308 | 7.184 |

| Mar-2006 | 4.537 | 7.072 |

| Apr-2006 | 4.495 | 7.12 |

| May-2006 | 4.432 | 6.98 |

| Jun-2006 | 4.331 | 7.001 |

| Jul-2006 | 4.081 | 7.175 |

| Aug-2006 | 4.411 | 7.091 |

| Sep-2006 | 4.498 | 6.847 |

| Oct-2006 | 4.454 | 6.727 |

| Nov-2006 | 4.622 | 6.872 |

| Dec-2006 | 4.552 | 6.762 |

| Jan-2007 | 4.59 | 7.116 |

| Feb-2007 | 4.481 | 6.927 |

| Mar-2007 | 4.657 | 6.731 |

| Apr-2007 | 4.534 | 6.85 |

| May-2007 | 4.531 | 6.766 |

| Jun-2007 | 4.639 | 6.979 |

| Jul-2007 | 4.43 | 7.149 |

| Aug-2007 | 4.508 | 7.067 |

| Sep-2007 | 4.481 | 7.17 |

| Oct-2007 | 4.278 | 7.237 |

| Nov-2007 | 4.278 | 7.24 |

| Dec-2007 | 4.323 | 7.645 |

| Jan-2008 | 4.223 | 7.685 |

| Feb-2008 | 4.039 | 7.497 |

| Mar-2008 | 4.012 | 7.822 |

| Apr-2008 | 3.85 | 7.637 |

| May-2008 | 4 | 8.395 |

| Jun-2008 | 3.67 | 8.575 |

| Jul-2008 | 3.762 | 8.937 |

| Aug-2008 | 3.584 | 9.438 |

| Sep-2008 | 3.21 | 9.494 |

| Oct-2008 | 3.273 | 10.074 |

| Nov-2008 | 3.059 | 10.538 |

| Dec-2008 | 3.049 | 11.286 |

| Jan-2009 | 2.763 | 12.058 |

| Feb-2009 | 2.794 | 12.898 |

| Mar-2009 | 2.493 | 13.426 |

| Apr-2009 | 2.271 | 13.853 |

| May-2009 | 2.413 | 14.499 |

| Jun-2009 | 2.388 | 14.707 |

| Jul-2009 | 2.146 | 14.601 |

| Aug-2009 | 2.294 | 14.814 |

| Sep-2009 | 2.434 | 15.009 |

| Oct-2009 | 2.376 | 15.352 |

| Nov-2009 | 2.419 | 15.219 |

| Dec-2009 | 2.49 | 15.098 |

| Jan-2010 | 2.706 | 15.046 |

| Feb-2010 | 2.561 | 15.113 |

| Mar-2010 | 2.652 | 15.202 |

| Apr-2010 | 3.097 | 15.325 |

| May-2010 | 2.9 | 14.849 |

| Jun-2010 | 2.728 | 14.474 |

| Jul-2010 | 2.929 | 14.512 |

| Aug-2010 | 2.869 | 14.648 |

| Sep-2010 | 2.782 | 14.579 |

| Oct-2010 | 3.026 | 14.516 |

| Nov-2010 | 3.072 | 15.081 |

| Dec-2010 | 2.909 | 14.348 |

| Jan-2011 | 2.917 | 14.046 |

| Feb-2011 | 3.065 | 13.828 |

| Mar-2011 | 3.132 | 13.728 |

| Apr-2011 | 3.099 | 13.956 |

| May-2011 | 3.032 | 13.853 |

| Jun-2011 | 3.194 | 13.958 |

| Jul-2011 | 3.417 | 13.756 |

| Aug-2011 | 3.138 | 13.806 |

| Sep-2011 | 3.557 | 13.929 |

| Oct-2011 | 3.422 | 13.599 |

| Nov-2011 | 3.215 | 13.309 |

| Dec-2011 | 3.527 | 13.071 |

| Jan-2012 | 3.653 | 12.812 |

| Feb-2012 | 3.517 | 12.828 |

| Mar-2012 | 3.837 | 12.696 |

| Apr-2012 | 3.627 | 12.636 |

| May-2012 | 3.696 | 12.668 |

| Jun-2012 | 3.785 | 12.688 |

| Jul-2012 | 3.587 | 12.657 |

| Aug-2012 | 3.637 | 12.449 |

| Sep-2012 | 3.614 | 12.106 |

| Oct-2012 | 3.729 | 12.141 |

| Nov-2012 | 3.741 | 12.026 |

| Dec-2012 | 3.64 | 12.272 |

| Jan-2013 | 3.77 | 12.497 |

| Feb-2013 | 4.023 | 11.967 |

| Mar-2013 | 3.891 | 11.653 |

| Apr-2013 | 3.84 | 11.735 |

| May-2013 | 3.829 | 11.671 |

| Jun-2013 | 3.864 | 11.736 |

| Jul-2013 | 3.829 | 11.357 |

| Aug-2013 | 3.893 | 11.241 |

| Sep-2013 | 3.955 | 11.251 |

| Oct-2013 | 4.076 | 11.161 |

| Nov-2013 | 4.073 | 10.814 |

| Dec-2013 | 3.977 | 10.376 |

| Jan-2014 | 3.906 | 10.28 |

| Feb-2014 | 4.160 | 10.387 |

| Mar-2014 | 4.210 | 10.384 |

| Apr-2014 | 4.417 | 9.696 |

| May-2014 | 4.608 | 9.761 |

| Jun-2014 | 4.710 | 9.453 |

| Jul-2014 | 4.726 | 9.648 |

| Aug-2014 | 4.925 | 9.568 |

| Sep-2014 | 4.678 | 9.237 |

| Oct-2014 | 4.849 | 8.983 |

| Nov-2014 | 4.886 | 9.071 |

| Dec-2014 | 4.877 | 8.688 |

| Jan-2015 | 4.965 | 8.979 |

| Feb-2015 | 5.144 | 8.705 |

| Mar-2015 | 5.109 | 8.575 |

| Apr-2015 | 5.334 | 8.549 |

| May-2015 | 5.357 | 8.674 |

| Jun-2015 | 5.323 | 8.299 |

| Jul-2015 | 5.668 | 8.266 |

| Aug-2015 | 5.370 | 8.029 |

Note: Shaded areas denote recessions.

Source: EPI analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey and Current Population Survey

Urban Outfitters gets into the holiday spirit by asking its employees to work for free

An internal memo to the staff of hipster retailer Urban Outfitters, which was leaked to Gawker, gives us a window into how the retailer’s Philadelphia-based parent company, URBN, plans to deal with the upcoming holiday rush. Their not-so-innovative idea: ask employees to work for free.

In a “call for volunteers,” URBN informs the staff that “October will be the busiest month yet for the [fulfillment] center, and we need additional helping hands to ensure the timely shipment of orders.” It goes on to explain to its employees that “as a volunteer, you will work side by side with your [fulfillment center] colleagues to help pick, pack and ship orders for our wholesale and direct customers.”

In short, URBN, whose executive staff took home a combined $12.2 million in compensation last year, is asking its employees to take time out of their weekends to commute to rural Pennsylvania and work in a warehouse—for free.

Unsurprisingly, this request is most likely illegal. According to the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), it is unlawful for a for-profit employer “to suffer or permit” someone to work without compensation—consequently, asking an employee who is not “exempt” to “volunteer” for a for-profit enterprise, whether they are salaried or hourly, is explicitly prohibited by the FLSA.

Failure to stem dollar appreciation has put manufacturing recovery in reverse

This week, President Obama announced the completion of negotiations on the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The TPP, which is likely to drive down middle-class wages and increase offshoring and job loss, has been widely criticized by leading members of Congress from both parties. Hillary Clinton, Bernie Saunders, and other presidential candidates have announced their opposition to the deal.

Meanwhile, U.S. jobs and the recovery are threatened by a growing trade deficit in manufactured products, which is on pace to reach $633.9 billion in 2015, as shown in Figure A, below. This deficit exceeds the previous peak of $558.5 billion in 2006 (not shown) by more than $75 billion. The increase in the manufacturing trade deficit in 2015 alone will amount to 0.5 percent of projected GDP, and will likely reduced projected growth by even more as manufacturing wages and profits are reduced.

U.S. manufacturing trade deficit, 2007–2015* (billions of dollars)

| Year | U.S. manufacturing trade deficit (billions of dollars) |

|---|---|

| 2007 | 532.222 |

| 2008 | 456.240 |

| 2009 | 319.471 |

| 2010 | 412.740 |

| 2011 | 440.602 |

| 2012 | 458.692 |

| 2013 | 449.276 |

| 2014 | 515.131 |

| 2015 | 633.915 |

* Estimated, based on year-to-date trade data through August 2015

Source: Author's analysis of U.S. International Trade Commission Trade DataWeb

The growth of the manufacturing trade deficit is starting to have an impact on manufacturing employment, which has lost 27,300 jobs since July 2015, as shown in Figure B, below. Growing exports support U.S. jobs, but increases in imports cost jobs, so even if overall exports are growing, trade deficits hurt U.S. employment—especially in manufacturing, because most traded goods are manufactured products. Although the United States had regained more than 800,000 manufacturing jobs since 2010, the low point of the manufacturing collapse after the great recession, overall manufacturing employment is still 1.4 million jobs lower than it was in December 2007.

ACA excise tax on expensive health plans is an unambiguous pay cut

The Affordable Care Act is making the U.S. health system much more efficient and fair. One provision of it, however, remains controversial, even among those strongly supportive of the overall law. This is the 40 percent excise tax on the marginal cost of expensive health plans, sometimes very misleadingly referred to as the “Cadillac Tax.” Defenders of this tax, and even many reporters, have claimed recently that the tax will “give Americans a raise” or will “raise incomes.” These claims are wrong. Instead, the excise tax— even in the best case—is an unambiguous cut in after-tax pay for workers.

Beginning in 2018, the tax will be levied on the cost of single plans in excess of $10,200 a year, and non-single plans in excess of $27,500. The point of the tax is to nudge workers into taking thinner health plans—those with lower premiums that stay under the threshold for the tax. But choosing plans with lower premiums will generally lead to higher out-of-pocket costs – higher deductibles, co-pays and/or other forms of cost sharing. This increased cost-sharing is the point of the tax, not a byproduct. By boosting the marginal cost of each new episode of obtaining health care, the theory is that health consumers will shop more wisely and cut back on unnecessary care. We have strong reservations about leaning on this dynamic as effective cost containment, but for now I’ll focus on a side claim made by defenders: that a happy consequence of accepting plans with lower premium costs is that workers will see higher wages.

The theory for this is that if employers cut back on contributions to health insurance premiums as workers choose thinner plans, more money will become available to boost non-health care compensation—wages or other fringe benefits. This presumed increase in wages actually accounts for a significant share of estimated revenue that will be raised by the tax. (I should note that if the compensating wage boost stemming from lower employer premium payments does not happen, this does not necessarily mean that the tax won’t raise money. Lower premium costs and unchanged wages paid by employers imply a rise in business income or profitability, and this higher profitability should mean higher tax payments by employers.)