Forced binding arbitration robs workers and consumers of basic rights

The New York Times has published two parts of a three-part series about the epidemic of arbitration clauses that have cropped up in millions of transactions between corporations and their customers and employees. The clauses are routinely included in employment contracts, cell-phone contracts, consumer product purchase agreements, cable subscriptions, rental agreements, and a multitude of financial transactions, as a way to prevent injured parties from having their day in court. Giving up the constitutionally protected right to sue in state or federal court is a big deal and is often the result of ignorance and deceit: millions of people have no idea the clauses are there in the fine print of contract provisions written in legalese that few individuals ever read or comprehend. They don’t find out they’ve lost their rights until they need them.

Individuals give up not just their right to go to court but all protections regarding the venue of any hearing their claim will receive (for example, the agreement might require arbitration in a city a thousand miles away). They might give up certain remedies and the right to appeal even if the arbitrator gets the law completely wrong, and give up the essential right to join with other victims to file a class action, especially important when each claim is small and no single individual could rationally pay to hire a lawyer and bring a lawsuit for such a small sum.

The myth is that arbitration is preferable because it allows individuals to resolve their grievances easily, quickly, and cheaply. In fact, arbitration can be more expensive for a plaintiff than a civil suit because instead of a small filing fee in court, the plaintiff will have to pay half of the arbitrator’s fee, or sometimes all of it if the arbitration clause includes a “loser pays” provision. Legal fees can be ruinous, and the Times story relates the case of a woman who owes $200,000 in attorney fees after losing a case in which her former employer allegedly destroyed evidence.

Perhaps the worst aspect of the forced arbitration epidemic is the loss of a neutral trier of fact. Unlike judges who have lifetime appointments to the bench and are protected from financial pressure, arbitrators rely on the companies to use them again and again, creating a financial pressure to please the corporation that will have many arbitration cases in the future rather than the individual plaintiff, who will probably never use an arbitrator again.

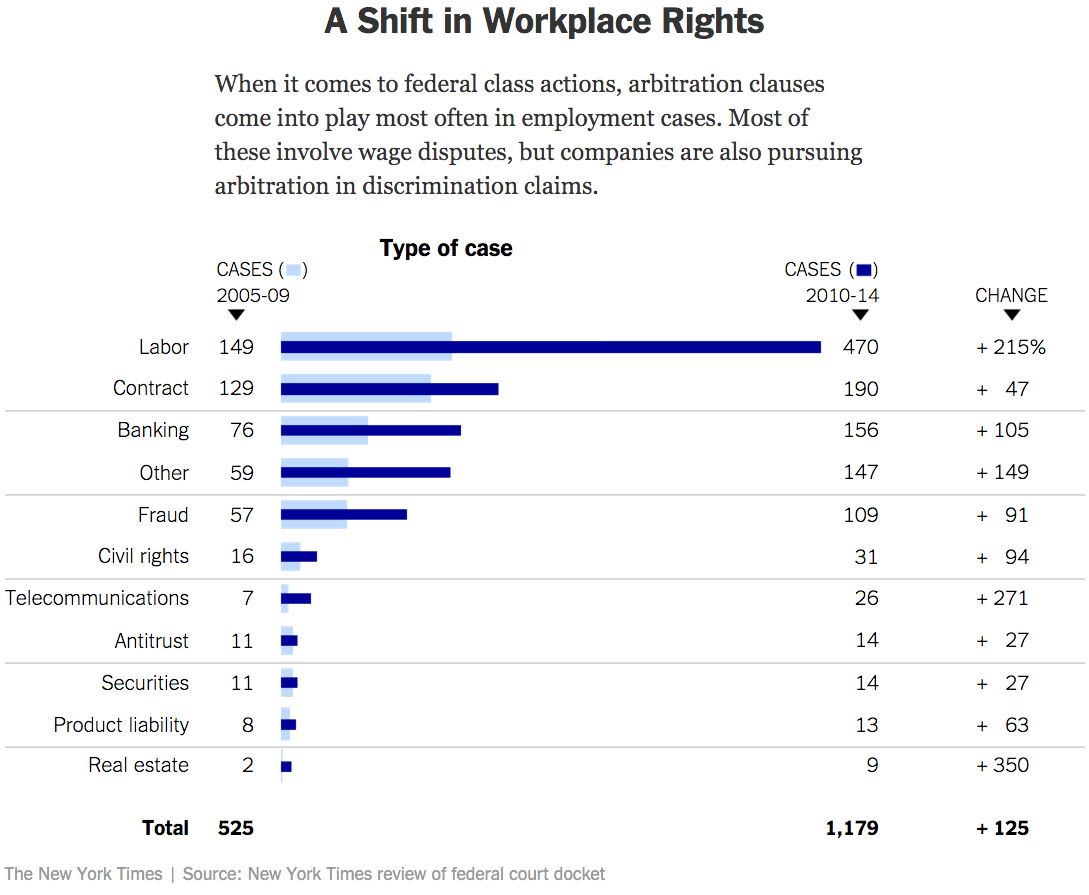

EPI plans to publish an overview of the arbitration epidemic soon, written by two of the nation’s top legal experts on the subject, Alex Colvin of Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations and Katherine Stone of UCLA’s School of Law. Their paper will focus on the damage compulsory arbitration is doing to employment law, where the use of such clauses has exploded. As a graph in the New York Times story reveals, employment cases are the area of the law that has seen the largest increase in arbitrations and now account for 40 percent of all arbitration cases.

In our 12-point Agenda to Raise America’s Pay, we recommend that forced binding arbitration be prohibited in employment contracts (agenda item number 7).

Enjoyed this post?

Sign up for EPI's newsletter so you never miss our research and insights on ways to make the economy work better for everyone.