What should have been different this time? The policy response

Eons ago, in blogtime, Ezra Klein wrote an excellent piece on policymaking in the face of the Great Recession and its aftermath. It’s a long piece with plenty to recommend, but I’ll just spend some time lingering over his reliance on the now-famous finding of Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff (and the IMF) that recessions accompanied by financial crises tend to be followed by much slower and less robust recoveries.

This finding is true and useful but far too often misinterpreted. There is nothing inherent in the economics of financial crises that makes slow recovery inevitable – they just require that policymakers figure out how to engineer more spending in their wake, same as in response to all other recessions.

Rather, the real problem they pose to policymakers is that engineering such spending increases in the wake of financial crises often requires policy responses that seem unorthodox or radical relative to the very narrow range of macroeconomic stabilization tools that enjoy support across the ideological spectrum. To put this more simply – they require policymakers do more than watch the Federal Reserve pull down short-term interest rates. For decades, all recession-fighting was outsourced to the Fed’s control of short-term “policy” interest rates – this despite the fact that in the U.S. this recession-fighting tool hasn’t actually been all that successful since the 1980s (see Table 2 in this paper).

The best response to a recession that is either so deep or so infected by debt-overhangs that conventional monetary policy is not sufficient, is simply to engage in lots of fiscal support – think the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) – but (as Ezra notes) much, much bigger in the case of the Great Recession.

But, this kind of discretionary fiscal policy response to recession-fighting (and jobless-recovery fighting) had fallen deeply out of favor in the same decades that saw increasing reliance on conventional monetary policy[1]. In fact, advocating fiscal policy that was up to the task of providing a full recovery in the wake of crises that defanged conventional monetary policy somewhere along the way got labeled radical, rather than simply nuts-and-bolts economics.

Further, this rejection of discretionary fiscal policy was done on very thin analytical reeds – essentially the fear was that it took too long to debate, pass, and see an effect from fiscal policy – and that if the recession was “missed” in real-time by policymakers, we would end up providing lots of fiscal support to an already-recovered economy – and might even cause economic overheating that would lead to runaway inflation and interest rate spikes.

This fear led to the strange mantra in the debate over fiscal stimulus in 2008 that policy had to be targeted, temporary and timely – which basically ruled out most things but tax cuts. But, given that the last three recessions have seen extraordinarily sluggish return to job-creation in their wake, this timely obsession was clearly misplaced (and, plenty argued so in real-time).

So we’ve come to what is, I think, a big gap in Ezra’s piece – the repeated (and correct) insistence that the political system just couldn’t accommodate what nuts-and-bolts economics indicated was needed (i.e., large-scale fiscal support) for a full recovery without examining just how we found ourselves with a political system that has become deeply stupid about fighting recessions and jobless recoveries. Read more

Baby steps toward fixing our schools

There are now two competing proposals to fix America’s aging public school buildings and, coincidentally, give jobs to thousands of construction and maintenance workers. One will work; the other won’t.

The first, the one that would be effective, was proposed by President Obama and introduced by Connecticut Rep. Rosa DeLauro (H.B. 2948) and Ohio Sen. Sherrod Brown (S. 1597). Fix America’s Schools Today! (FAST) is a straightforward federal grant program that would send $25 billion directly to state education agencies and local school districts by formula, accounting for need, and permitting them to hire contractors to make repairs, do deferred maintenance, and make improvements in public K-12 school buildings and facilities. We estimate it could put 250,000 people back to work.

On Oct. 12, Virginia Senators Jim Webb and Mark Warner introduced the second, more complicated yet very limited bill to rehabilitate only the nation’s ‘historic’ schools, The Rehabilitation of Historic Schools Act of 2011. According to their press release, Virginia Gov. Bob McDonnell and U.S. House Majority Leader Eric Cantor also support their proposal.

As my colleague, Jared Bernstein, wrote in his blog last week, it’s good to see bipartisan support for fixing up our public school buildings. And it’s true that, as Jared pointed out, “the first step towards fixing a problem is recognizing the problem and taking responsibility for it.”

Unfortunately, the Webb-Warner Historic Schools Rehabilitation Tax Credit plan is so limited in scope that it would accomplish little in terms of either job creation or school modernization.

Their plan offers developers a federal tax credit to enter into public/private partnerships with states and school districts to help pay for modernization of schools that are on the National Register of Historic Places.

Private partners would have to purchase the historic public school building and then lease it back to the school district. As part of the sale-lease-back agreement they would modernize the historic schools using the incentive of the federal tax credit to reduce the overall cost.

However, unlike FAST, the tax credit program is small, convoluted, and slow. The President proposed rehabbing 35,000 school buildings, but there are fewer than 1,000 public schools on the National Register of Historic places. The policies, approvals, and agreements needed for school districts to enter into developer partnerships (the kind of bureaucratic and legal red tape politicians normally deplore) add a level of complexity that will take time and limit the impact on both school repairs and jobs. And poorer school districts – the ones that need help the most — just won’t be able to make use of a tax credit—they need a grant to make these repairs.

School repair and modernization shouldn’t depend on the desire of developers to secure tax credits. We ought to be simplifying the tax code, not adding to its loopholes. Having recognized both the need to improve our educational infrastructure and a federal role, Webb, Warner and Cantor should join with the president in supporting FAST.

At the very least, even if they’re wedded to using the tax code to fund school modernization, they should expand their vision beyond a few hundred historic buildings. The problems of unemployment and substandard school infrastructure are far too big for such a narrow solution.

Who’s middle class? It depends…

All politicians say they want to protect the middle class, but who belongs to the middle class? The Census Bureau puts the median household income at a shade under $50,000, and a broad definition (leaving out the bottom and top twenty percent) gets you a range of about $20,000 to $100,000, ignoring differences in household size and regional cost of living.

But the definition of “middle class” seems to expand or contract depending on the context. When it comes to shielding taxpayers from tax increases, the “middle class” tends to extend well above the $100,000 threshold. For example, the Alternative Minimum Tax is “patched” by Congress each year in the name of protecting the middle class, even though roughly three-fourths of the forgone revenue comes from households making more than $100,000. Similarly, while campaigning for president, Barack Obama famously pledged not to raise taxes on married couples with incomes under $250,000 or single taxpayers with incomes under $200,000.

But when it comes to Social Security cuts, the middle class seems to shrink. The co-chairs of the president’s Fiscal Commission, for example, proposed cuts for the “most fortunate” that reduced benefits for Social Security’s prototypical medium earner (a worker earning around $43,000 in 2010) by 19 percent. Though some of this would come from across-the-board cuts like a lower cost-of-living adjustment, even targeted (“progressive”) cuts would fall on those earning as little as $38,000.

Why go after middle class retirees? One reason is that there are few wealthy retirees and they don’t receive much in Social Security benefits. Only 7 percent of Social Security beneficiary “units” 62 and older had incomes above $100,000 in 2008 (this includes single retirees and married couples). Even if these upper-income retirees all received close to the maximum benefit of around $35,000, it’s hard to achieve substantial savings without going lower down the income scale or eviscerating benefits for higher-income retirees, who earned them through years of contributions and already rebate some through the income tax system.

While trimming benefits for high-income retirees doesn’t get you very far, a modest payroll tax increase on high-income workers does. Currently, earnings above $106,800 are exempt from Social Security taxes. Taxing all earnings equally would all but eliminate Social Security’s long-run shortfall. Alternatively, removing the cap on the employer side and indexing it to cover 90 percent of earnings on the employee side (as it did in the early 1980s when Social Security was in long-term balance) would close around 70 percent of the shortfall if benefits are based on the employee contribution. This has the advantage of neither raising employee taxes nor creating outsize benefits.

Despite strong public support for lifting or eliminating the payroll tax cap, politicians like Texas Governor Rick Perry insist on keeping alive the idea that the projected Social Security shortfall can and should be closed by “means testing” benefits for high-income retirees. Going after AARP-card-carrying Lexus drivers living in gated communities (as Fiscal Commission co-chair Alan Simpson characterized opponents of benefit cuts) may sound like a good idea until you realize how elastic class categories are. In fact, even those of us who drive old Chevy Prizms and live in rental apartments had better watch out.

California’s governor refuses to add more speedometers to a broken education vehicle

In an eloquent veto message of a school accountability reform bill last weekend, California Governor Jerry Brown articulated an alternative to the narrow standardization of schooling and the promotion of misleading quantitative test score measures that have characterized American education in the last generation.

Most observers recognize that as government increasingly held schools and teachers accountable primarily for the math and reading test scores of their students, schools inevitably narrowed their curricula to minimize attention to other important educational outcomes, substituted test preparation and test taking skills for real learning, and even engaged in cheating to meet politically determined targets.

Some policymakers have recently attempted to address these problems by advocating accountability for “multiple measures.” Their reasoning has been that the corruption of education that results from a near-exclusive focus on basic skills in math and reading can be ameliorated if other indices can be added to accountability systems to supplement the math and reading test scores. This was the goal of the California bill, sponsored by liberal Democrats, and sent to Brown for signature.

But because other important outcomes of education – like character, inquisitiveness, citizenship, civic awareness, historical reasoning, scientific curiosity, good health habits – cannot be standardized like math and reading scores, proponents of “multiple measures,” like the California senators who crafted the bill, are left with adding indices like attendance rates, parent satisfaction, graduation rates, the number of students taking advanced placement courses, and the like. But this does little to divert schools’ obsession with math and reading test scores, since they remain the only academic outcomes that count.

As Brown observed, “adding more speedometers to a broken car won’t turn it into a high-performance machine.”

In his veto message, Brown recalled an aphorism of Albert Einstein: “Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted, counts.” The bill, Brown said, “nowhere mentions good character or love of learning. It does allude to student excitement and creativity, but does not take these qualities seriously because they can’t be placed in a data stream.”

Brown invited the legislature to work with him to devise a truly workable accountability system for education, one that relies on qualitative evaluations by “panels [that] visit schools, observe teachers, interview students, and examine student work.”

The Broader, Bolder Approach to Education campaign has advocated such a system, and described it in more detail in a statement issued by nationally prominent educators and policy experts. The system is also described in Grading Education: Getting Accountability Right. If the panels that Brown advocates are constituted with appropriate experts in curriculum and instruction, and include members of the public as observers, they have the potential to finally provide citizens with the ability to distinguish effective from ineffective schools in their state and communities.

It is encouraging that California State Senator Darrell Steinberg responded to Brown’s veto message with a willingness to work with him to design such an accountability system. Should they succeed, it could signal that some in the nation may finally be ready to turn away from a well-intentioned but destructive reduction of schooling to the standardized tests that can, at best, measure only a small aspect of education.

Test score gaps refuse to budge, plead poverty

High-profile education “reformers” in Washington, D.C., New York, and Chicago have asserted over the past decade that test-based accountability, whether for teachers (D.C. and N.Y.) or schools (Chicago) is key to student improvement. They have accused those who note the well-documented impact of poverty on academic achievement of “making excuses.”

Ten years in, what do they have to show for these resource-consuming “no excuses” initiatives? The answer seems to be very little, and maybe less than that. Recent reports on Chicago and Washington schools find little improvement in student achievement overall, with the white-black and rich-poor achievement gaps reformers promised to close actually widening in some cases. In New York, rewards for high-performing teachers proved so ineffective in raising test scores that the city abandoned them.

Michelle Rhee’s tenure as D.C. Public Schools Chancellor provides a stark example. Rhee invested $4 million in her new teacher evaluation system in 2009 and fired 1,000 educators in her 3 ½ years based heavily on test scores biased in favor of wealthier students. Current status? A stubborn achievement gap and apparently rampant cheating. In schools serving lower-income students especially, high stakes have also likely led to the substitution of real learning for test prep, to those students’ detriment.

Two D.C. schools illustrate the strong correlation between test score disparities and the concentration of low-income students. In a January Washington Post article, Bill Turque notes that at Horace Mann Elementary School, with a 73 percent white student body and only 4 percent of students qualifying for free or reduced-price lunch, around 90 percent of students meet or exceed district achievement standards. Across town at Stanton Elementary School, where 85 percent of students qualify for free or reduced priced lunch, only 9 percent of students met or exceeded 2011 math and reading standards.

Rhee’s regime of test prep for students and tough accountability for teachers did little to narrow these gaps because it ignored the more complex and challenging issue of poverty. Ineffective teachers and principals clearly impede learning. But the variation in teacher quality is overwhelmed by the variation in social and economic conditions that promote (or limit) children’s readiness to learn. The failure of a small-carrot large-stick approach to attaining teacher “excellence” should give serious pause to the certainty of “reformers” like Michelle Rhee. It also challenges their assertions that acknowledging the effects of lack of early childhood education, excess mobility, family stress, and poor health on student outcomes amounts to “excusing” teachers. Rather, the “no excuses” crowd must stop excusing itself.

Big recession, big budget deficits

Fiscal year 2012 kicked off on Oct. 1 to an economy roughly $1 trillion (-6.2 percent) below potential economic output—the level of economic activity that would be associated with full employment and industrial capacity utilization. This economic slack has significant consequences for the budget deficit because revenues are lower and more Americans rely on the social safety net.

Recently, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that this portion of the budget deficit attributable to economic weakness is $340 billion this fiscal year (FY2012). In other words, if the unemployment rate were closer to 5 percent, the budget deficit would be around a third lower than its projected level ($973 billion, or 6.2 percent of GDP). CBO’s methodology and older estimates can be found here.

While sizable, these estimates understate the impact of the recession on the budget by only focusing on economic variables and ignoring deliberate legislative efforts to prop up the economy. Objectively stimulative provisions in last December’s tax and insurance compromise added $124 billion to this year’s deficit (in addition to the $299 billion added to the deficit by extending current tax policies), the Recovery Act added $49 billion, and supplemental stimulus extensions (UI, helping states with their Medicaid bills, and a teachers’ jobs fund) added $1 billion. Similarly, tax deal stimulus added $157 billion to last year’s deficit, the Recovery Act added $163 billion (net of the alternative minimum tax patch, which wasn’t stimulus), and supplemental stimulus extensions added roughly $47 billion to last year’s deficit.

Adjusting the budget deficit (less cyclical contributions) for these legislative decisions, the effective impact of the recession is closer to $699 billion last year and $514 billion this year, or about 54 percent of last year’s actual budget deficit and 53 percent of this year’s deficit.

Even adjusting for legislated economic support underestimates the impact of the recession, because many economically sensitive projections, such as decreased revenue from capital gains realizations, show up in CBO’s ‘technical revisions’ rather than the cyclical economic revisions. Technical revisions are residual non-legislative, non-economic changes in projected receipts and mandatory outlays, influenced by factors such as the distribution of tax filers through income brackets or effective tax rates. Kitchen (2003) finds that economic and technical revisions demonstrate a statistically significant and close relationship, particularly with personal income receipts. Since the start of the recession, technical revisions to CBO’s budget outlook have cumulatively added $139 billion to the FY2011 budget deficit and $246 billion to the FY2012 deficit.

Stripping out the combined impact of cyclical economic factors, stimulus legislation, and technical revisions, this year’s structural deficit would be $223 billion, or 1.4 percent of GDP. Last year’s structural deficit would have been $446 billion, or 3.0 percent of GDP. Put differently, a host of recession-related factors account for at minimum half and upwards of 65 percent of last year’s deficit and 77 percent of this year’s deficit.

This analysis shows just how sensitive the budget is to economic activity and employment. Unfortunately, the economy faces a big drop off in deliberate fiscal support between last year and this year. Goldman Sachs recently estimated that under current law, U.S. fiscal policy will shave 1.8 percentage points from GDP growth in calendar year 2012 (or one percentage point even if the payroll tax cut is extended). We estimate that the debt ceiling deal’s initial spending cuts, coupled with failure to extend the payroll tax cut and UI, would shave 1.5 percent off growth and lower employment by 1.8 million jobs in 2012.

Congress needs to change course and enact more economically supportive policy to put millions of Americans back to work and improve the fiscal outlook.

Persistent and acute state budget deficits? It’s (still) the economy

Researchers from the UC Berkeley Institute for Research on Labor and Employment released a paper today that shows clearly and persuasively that the state budget crisis that continues to cripple most states has been caused by the bursting of the housing bubble and the persistent recession (and very weak recovery), not as many contend, by the presence of public sector unions.

The authors, labor economist Sylvia Allegretto, Ken Jacobs, and Laurel Lucia, connect the dots: the economy fell off a cliff and unemployment hit double digits, simultaneously increasing demands for state services and decimating state tax systems reliant on income and consumption, and then political opportunists lined up to identify scapegoats for widespread state revenue crises. Allegretto et al.’s paper separates the research data wheat from the political rhetoric chaff.

Step one shows that state and local government employment has remained remarkably consistent over the past 30-plus years, hovering between 14 percent and 15 percent as a share of total non-farm employment. During the recession, it bumped slightly above 15 percent primarily because the denominator, total employment, shrunk dramatically. Can the current acute fiscal distress be blamed on steady public sector employment? Hardly.

As seen in the map, there is considerable variation between states in the share of total employment comprised of state and local government employees. The states with the largest share of state and local government employees may surprise some – it’s generally not states that are normally associated with “big government.” Moreover, in step two, the authors demonstrate that there is no statistical correlation between higher public union density and share of public sector employment.

Steps three and four show that public sector compensation as a share of state budgets has actually declined over the past two decades, and summarizes new research (including IRLE research, The Truth About Public Employees in California: They are Neither Overpaid Nor Overcompensated) showing that public sector employees are not overcompensated.

Having demonstrated that public sector workers are not to blame for state fiscal woes, the authors drill down to the real cause of state fiscal distress – the bursting of the housing bubble. They find that regardless of public sector union strength, “house price declines [resulting from the bursting of the housing bubble] were, to a large extent, a central reason why state budgets are in such dire straits.”

The real take-away of this paper – “It’s the economy, stupid!” – highlights the path needed to further revive state fiscal conditions. Putting American workers back to work will breathe new life into both income tax revenues and state sales taxes. It’s time to focus on the real crisis facing America, rather than being distracted by so many paper tigers.

Snapshot: Will outcome of new trade agreements be any better than NAFTA?

Last night, Congress passed a free trade agreement for the first time since 2007. In fact, it passed three.

Behind vast Republican support, the House and Senate approved trade deals with Colombia, Panama and South Korea. This came, of course, one day after Senate Republicans killed President Obama’s jobs bill. These trade agreements should be a boon for jobs, right?

Not so fast. Robert Scott, EPI’s Director of Trade and Policy Manufacturing Research, estimates that 214,000 net U.S. jobs will be lost or displaced in the first seven years under the FTAs with Colombia and South Korea.

“With 14 million unemployed, these deals will only further burden our domestic economy, which is already teetering on the brink of another recession,” wrote Scott in a statement today.

Supporters of the FTAs, however, claim the deals will create tens or hundreds of thousands of U.S. export jobs. That would sound great if it wasn’t so naive.

As Scott points out in this week’s snapshot, trade both adds to and subtracts from the demand for workers. While the growth of exports supports domestic employment, the increase of imports displaces American jobs. Scott says counting export jobs while ignoring imports is like “trying to run a business while ignoring expenses.”

In 1993, the Clinton administration also had high hopes for job creation when the U.S. and Mexico signed the North American Free Trade Agreement. They claimed NAFTA would “create an additional 200,000 high-wage jobs related to exports to Mexico by 1995.”

Before NAFTA, the U.S. had a trade surplus with Mexico. By 2010, the U.S. had a trade deficit with Mexico and had lost or displaced 682,900 jobs. Free trade, anyone?

Clive, don’t change the subject

Clive Crook blogs on my paper, Regulatory uncertainty: A phony explanation for our jobs problem, and finds it “clever and interesting but not all that persuasive.” He reports that the paper finds “Trends in investment (this recovery, weak as it may be, has been “investment-led” by historical standards), in hiring, and in hours worked all suggested that lack of overall demand is the problem,” and does not dispute any of the conclusions. Crook just thinks I should have written a different paper:

“First, the focus on regulatory uncertainty seemed too narrow. What about other kinds of policy-induced uncertainty? Second, its target–the idea that regulatory uncertainty as opposed to weak demand is the cause of slow growth–is a straw man. Who is denying that weak demand is a factor, or even the larger factor of the two?”

Well, I do think there are a ton of important people denying that there is any demand problem whatsoever, or at least one that can be addressed by policy. How else can there be an essentially uniform view among the Republicans that the initial stimulus had zero effect? How else to explain that the program of each candidate for the Republican presidential nomination has an exclusively ‘supply-side’ approach which basically boils down to fiddling with the structure of taxation? How else to explain the recent contention by the top four Republican leaders in Congress that the Federal Reserve should take no further policy actions to expand demand? It is hard not to notice that conservatives and Republicans are seeking immediate reductions in federal spending, which can only exacerbate any demand-side problem. Perhaps Crook should supply some examples of leading conservative economists and Republican leaders saying there is a demand problem, that it is a ‘larger factor’ than uncertainty, and of the proposals they are advancing to address the demand shortfall.

That my analysis focused on regulatory and tax uncertainty was not arbitrary, of course; this is what conservative economists, business trade associations and Republican politicians are saying is the sole reason for high unemployment, and I offered several (of numerous possible) examples. They do not talk about other types of uncertainty when trying to explain persistent high unemployment and slow job growth. They focus on regulations and taxation because they are claiming that Obama administration policies and proposals are inhibiting job growth. In fact, just last week, House Republicans “dared President Obama and other Democrats to support two bills that would delay two pending Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) rules, a move they said would have a more immediate effect on jobs than anything Obama has proposed.” I am confused why Crook does not understand that examining the employment and investment impact of tax and regulatory uncertainty is a key question in current policy debates.

Crook suggests a broader uncertainty lens, which to me is changing the topic. He points to a recent paper by Scott Baker, Nicholas Bloom and Steven Davis which attempts to measure uncertainty and finds:

“Index values are high in recent years and show clear jumps associated with the Lehman bankruptcy, the 2010 midterm elections, the Euro crisis and the U.S. debt-ceiling dispute. … Greater policy uncertainty in 2011, relative to 2006 levels, lowers GDP by about 1.4 percent and employment by about 2.5 million…”

I am not persuaded that the measurement of uncertainty in this paper is worthwhile since their metric relies heavily on news citations; consequently, when the conservative echo chamber screams about a topic their index captures these claims as real economic concerns. Nevertheless, it is interesting that the paper’s results in no way support the conservative/Republican/business association claim that Obama’s policies have inhibited job growth. Note that the paper’s conclusion estimates the impact of uncertainty from 2006 to the first half of 2011, so it covers much ground before Obama was even elected. If you look at the paper you will see that the main spikes in policy uncertainty (see their Figure 1 below) are due to the Lehman implosion, the TARP legislative debate and the banking crash, all of which pre-date Obama, and that by far the largest spike in uncertainty under Obama was the ‘debt ceiling dispute.’

Now, in my view and I think in most objective observers’ views, the debt ceiling fiasco was a crisis totally manufactured by Republican politicians. So, if uncertainty hurt job growth, then one should point at those responsible for the financial crisis and the debt ceiling debacle. Crook has clarified one thing for me. Anyone claiming uncertainty is holding back the economy needs to identify the particular types of uncertainty and who’s responsible for those uncertainties—Obama, Republican policymakers, both or neither. The case that Obama’s policies are generating job-killing uncertainty has not been substantiated and the intense emphasis by conservative/Republican/ business association leaders on tax and regulatory uncertainty is a counterproductive distraction from advancing the demand-side policy changes necessary to move the economy forward.

Blame who?

In an interview with the Wall Street Journal, GOP presidential candidate Herman Cain responded to a question about the Occupy Wall Street protests by saying, “Don’t blame the big banks. If you don’t have a job and you’re not rich, blame yourself.”

Here are the facts: This morning, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released new data from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey showing that there were nearly 3.1 million job openings in August. However, we know from other BLS data that there were 14 million unemployed workers in August. In other words, there were nearly 11 million more job seekers than job openings.

The ratio of unemployed workers to job openings is now 4.6-to-1. A job seeker’s ratio of more than 4-to-1 means there are literally no jobs available for more than three out of four unemployed workers. In a given month in today’s labor market, the vast majority of the unemployed are not going to find a job no matter what they do. It is wrong, not to mention cruel, to call this their fault.

Mr. Cain went on to explain that he doesn’t “understand these demonstrations and what is it that they’re looking for.” For many, the answer is simple: jobs. National politics wrongly vilifying the unemployed while ignoring the economic fundamentals of a severe aggregate demand slump, however, are blocking an appropriate fiscal response that could put millions of Americans back to work.

Congress aims for “continuous improvement” from students

In education policy, Congress and President Obama’s administration continue to seek an unrealizable national whip that will somehow transform American schools for the better. These efforts ignore both evidence and common sense.

The latest example is a proposal developed by Senate Democrats to re-authorize the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (known recently as “No Child Left Behind,” or NCLB). Democratic Senator Tom Harkin of Iowa, chairman of the Senate education committee, has drafted a bill that will relieve states of having to meet federally specified achievement goals in math and reading. Instead of requiring all students to be “proficient” in these basic skills by 2014 (as NCLB demands), or to be “college ready” by 2020 (as the Obama administration proposes), the Harkin bill will require only that schools show “continuous improvement” for all students, and for students from low-income families, those who don’t speak English, minority students, and students with disabilities (see page 52 of the draft bill).

According to a report in Education Week, “state and local officials likely will be exchanging high-fives, since that would give them much of the flexibility they’re looking for.”

They are in for a shock. “Continuous improvement” is no more reasonable or achievable than “proficiency for all,” or universal college readiness.

Of course, citizens should expect every public school to strive for its peak level of performance, but some schools have much farther to go to reach this level than others. Unlike present policy, a well-designed accountability system could judge how far each school can and should go, and whether it is on the right track to get there for the several populations it may serve. In each case, this is a difficult judgment to make, and a slogan is no substitute. In this regard, a single one-size-fits-all metric such as “continuous improvement” is no better than “proficiency for all.” The Broader, Bolder, Approach to Education campaign has described the outlines of a more reasonable accountability system, and a book, Grading Education, goes into more detail.

NCLB’s attempt to require all students to be proficient at a challenging level led to the absurd result that nearly every school in the nation was on a path to be deemed failing by the 2014 deadline. The demand ignored an obvious reality of human nature – there is a distribution of ability among children regardless of background, and no single standard can be challenging for children at all points in that distribution.

Expecting all children to be college-ready suffers from the same problem, and more. In a nation where 32 percent of all young adults now earn bachelor’s degrees, and where the Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that only 30 percent of job openings by 2018, even in a healthy economy, would require a bachelor’s degree or more, the notion that 100 percent of students would be able to succeed in an academic college by 2020 is even more fanciful.

So why not “continuous improvement” instead? It’s a nice slogan, borrowed from a management fad promoted by W. Edwards Deming and others who thought this was the key to Japanese auto manufacturing success. But while consistent attention to small improvements makes sense as a management tool, no company has ever continuously improved, overall, indefinitely. There are spurts of improvement, and plateaus, and then the most successful companies fade, to be overtaken by others. No management expert would recommend that firms be dismantled if they are consistently profitable, but just not more profitable year after year after year.

But continuous improvement will now, if Senate Democrats have their way, be the trajectory for every school in the country, by law. Read the rest of my commentary here for more on why the expectations of Congress have no basis in reality.

Is Grover’s pledge losing gravitas?

Back when the “Gang of Six” was the fiscal flavor of the week and Sen. Tom Coburn (R-Okla.) was sparring with Grover Norquist over ethanol subsidies, I wrote that Norquist’s Taxpayer Protection Pledge is the height of fiscal irresponsibility. The pledge unconditionally rejects any net reduction in tax credits, deductions, or increase in rates unless matched dollar-for-dollar by some other tax reduction. (The pledge should have lost some of its gravitas when conservatives decided it didn’t apply to the payroll tax cut enacted last December.)

Since then, a rigid refusal to restore any revenues from levels diminished by current tax polices led Republican leadership to repeatedly walk out of debt ceiling negotiations, first with Vice President Biden and then again with President Obama. Instead of a grand bargain containing more desperately needed support for the faltering economy, our political system delivered an eleventh hour debt ceiling deal that prompted a credit rating downgrade from Standard & Poor’s, albeit on specious grounds (they made a $2 trillion baseline error but continued with the downgrade based strictly on political judgments). A stage of Republican presidential candidates unanimously declared that they would oppose a budget deal with 10 dollars in spending cuts for every dollar in new revenue.

Now, an impasse over revenue suggests that the super committee (tasked with negotiating the second phase of the debt ceiling deal) will go down in flames. This would trigger further discretionary spending cuts—the $111 billon cut slated for FY2013 would wallop GDP growth a year from now—and all but rule out more near-term fiscal support (due to limited borrowing headroom). The pledge is also hindering initiatives to put millions of Americans back to work; House Majority Leader Eric Cantor (R-Va.) recently proclaimed the American Jobs Act dead, having objected to its revenue offsets. Advantage Norquist?

Not so fast. Last Tuesday, Rep. Frank Wolf (R-Va.) excoriated Norqusit for guarding spending through the tax code, obstructing tax reform, and thwarting deficit reduction deals. “Have we really reached a point where one person’s demand for ideological purity is paralyzing Congress to the point that even a discussion of tax reform is viewed as breaking a no-tax pledge?” Wolf, who is one of only six House Republicans who have not signed Norquist’s pledge, came to Coburn’s defense a little too late, but this is nonetheless encouraging. Shortly thereafter, Taxpayer Protection Pledge signee Sen. John Thune (R-SD) said that Congress can’t be “bound by” pledges if it wants to enact comprehensive tax reform. Michael Gerson understands that pledge ideology rules out political agreement on long-term deficit reduction, and his attempt to fault the president’s emphasis on tax “fairness” as being equally unproductive is preposterous (he must have repressed all memories of the debt ceiling negotiations, and for good reason).

One by one, conservatives may be coming to the realization that the pledge is incompatible with fiscal responsibility of any form. Perhaps it helped that President Obama threatened to veto any budget deal that cuts Medicare without raising more revenue from upper-income households and businesses. Hopefully a critical mass of conservatives will stray from the herd of deficit peacocks and prioritize reducing the long-term budget deficit rather than blindly obsessing over the level of government spending.

Cato on China trade: Looking glass economics

My research has shown that the growth of the U.S.-China Trade deficit since 2001 has displaced or eliminated 2.8 million American jobs, and that eliminating currency manipulation by five countries in Asia (including China) could create up to 2.25 million U.S. jobs in the next 18-to-24 months. Dan Ikenson of the Cato Institute has responded with a graph which appears to show “a positive relationship” between “the bilateral trade deficit and jobs… when the deficit increases, U.S. employment rises; when the deficit shrinks, U.S. employment declines.” If Ikenson is right, there’s a simple policy solution: just eliminate exports!

Increasing exports reduces the trade deficit. In Ikenson’s world, this shrinks employment. In Ikenson’s model, eliminating exports increases the trade deficit and creates jobs. If he’s right, we should eliminate all exports, which totaled about $1.8 trillion last year. That will provide a HUGE boost to employment and the economy.

President Obama and all the business executives on his export council, such as Boeing Chair W. James McNerney, must be wrong if Ikenson is right. Exports are really the problem, and the president’s campaign to double exports will only make our terrible unemployment problems worse.

Last Wednesday, Senator Orrin Hatch used a graph very similar to the one developed by Mr. Ikenson to criticize my estimate that China trade has displaced 2.8 million jobs. The senator’s chart compares only U.S. imports and employment—he was careful to avoid bringing exports into the discussion. But his chart otherwise echo’s Ikenson’s work.

The basic problem with both charts it that they ignore basic economics and simple rules of national income accounting. In the national income accounts, exports contribute to Gross Domestic Product (and employment); imports reduce GDP and employment. Every quarter, the Bureau of Economic Analysis in the U.S. Department of Commerce publishes GDP statistics based on these national income accounts, and they have been a foundation of macroeconomics for generations. Economists from EPI and many other leading institutions, including the Federal Reserve bank of New York, have estimated the job impacts of trade in recent years by netting the job opportunities lost to imports against those gained through exports. But in the world of Senator Hatch and Mr. Ikenson, increasing imports are good for employment and exports are bad: what’s down is up and up is down. It’s economics Through the Looking Glass:

Alice laughed. “There’s no use trying,” she said: “one can’t believe impossible things.”

“I daresay you haven’t had much practice,” said the Queen. “When I was your age, I always did it for half-an-hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”

(Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass, Chapter 5).

In bad times, borrowing from yourself doesn’t make you poor

Last week on NPR, Robert Reich did a nice segment connecting the (not exactly cryptic) dots between high rates of unemployment, extraordinarily low interest rates, and the clear benefits of improving the nation’s infrastructure. However, he noted that the extraordinarily low interest rates meant that we could borrow cheaply (to fund infrastructure projects that would re-employ people – in case that part wasn’t obvious) “from the rest of the world.”

Actually, the low interest rates also mean that we (or the federal government) can borrow much more cheaply from ourselves (i.e., American households and businesses) too. And since the beginning of the Great Recession, we’ve been doing that more and more. While Federal borrowing has risen sharply (both a symptom of and sensible response to the recession), private savings – both household and business – have sharply increased. In fact, the upward swing in household and business savings is larger than the upward swing in federal government borrowing. This means that we are borrowing much less from the rest of the world than we were even before the Great Recession hit (in fact, it’s currently less than half as much as we were borrowing at the height of the housing bubble in 2005).

This is, of course, both bad and good news. The bad news is that the huge upward swing in private savings means that private spending is way, way down – and that’s why the economy remains so sluggish. The good news is that domestically financed increases in federal budget deficits means that, despite all the overheated rhetoric decrying them, there is no direct generational implication of them – we’re borrowing from ourselves and we’ll just pay it back to ourselves at a later date (for the long version of this argument, see here). More good news is that today’s low interest rates are no fluke or quirk that will quickly reverse – they are the inevitable consequence of this huge upward surge in private savings, and they will remain with us as long as the economy keeps operating so far below potential. Low interest rates, however, have not proven a panacea for growth, hence the need for bigger budget deficits to get us back to full employment.

Unfortunately, the past few quarters have seen U.S. borrowing from the rest of the world increase again – the mirror image of the increase in the trade deficit that has dragged on growth in that time. This trade deficit, in turn, highlights yet again the need to do something to allow the dollar to reach a level that keeps pre-Great Recession levels of trade deficits to return. If we do this, then we can borrow from ourselves to both fund economic recovery and a better infrastructure.

Taxing health benefits no silver bullet: Famous economists agreeing with us, Part 2

Prominent economists from the Urban Institute, John Holahan, Linda J. Blumberg, and others, published an insightful study this week on policies that might significantly contain the growth of health system spending. This post is going to focus on a policy that would not – the excise tax on high-cost employer-sponsored insurance plans.

There are two points they make abundantly clear. First, yes, the excise tax on high cost health plans will generate revenue. Second, it’s not going to do much to contain long term health cost growth.

The first point is indisputable. The second runs contrary of conventional wisdom about how effective taxing benefits will be in driving consumers to purchase less expensive plans. All else equal (firm size, region, age of workers at firm, etc.), less expensive plans require consumers to pay more when they seek care – higher coinsurance rates, higher deductibles, or the like. When consumers have to pay more, they will consume less. Voila! Rising health cost growth halted and we are saved.

Holahan and co-authors say it’s not so simple because spending on health care is not evenly spread across the population. And, I quote:

“Those least likely to be involved in the health care system—those with the lowest health care needs—will be most likely to be affected by increased cost-sharing. Given the strongly skewed distribution of health care spending, with 65 percent of total spending accounted for by only 10 percent of the population, significant health savings will not be achieved unless the highest spenders are affected as well.”

It sounds so convincing and reasonable to me, perhaps because I tried to make similar arguments during the health reform debate. It’s not that I had unusual foresight, but it’s just common sense when you look at the data. Back in March 2009 I argued:

“But the potential gains in cost containment from taxing health benefits are wildly overblown. We know that 80% of health costs are borne by 20% of the population. Serious cost containment measures should deal with bringing down the costs of the most expensive cases in our system (e.g., managing chronic diseases) rather than arguing over the much smaller amounts spent by the rest of the population. Policies fixated on reining in the first few hundred dollars of health spending do not effectively or efficiently deal with what is driving the high costs of the U.S. health system.”

However, as the health reform debate progressed, the policy virtues of taxing insurance benefits became exaggerated. And another set of prominent economists even identified the tax on expensive health insurance plans as one of just four critical elements of reform.

To sum up the Urban study’s main points that are consistent with those I raised two years ago:

1. Taxing benefits will have little impact on reining in health care spending because the distribution of health spending is skewed with few spending the vast majority of health dollars.

2. Increased cost sharing could lead to increased costs if patients respond to increased cost-sharing by substituting other services or delaying care until more expensive medical interventions are necessary.

3. Increased cost sharing could have significant negative health outcomes for people who have chronic conditions or are poor.

I might (and did in 2009) make another point: “high-cost” plans aren’t the same thing as “Cadillac” plans. The excise tax was often sold as taxing only those workers lucky enough to have lavish health coverage that demand minimal cost-sharing relative to normal plans (hence they were “Cadillac” plans). But in the market for health insurance, plans are expensive for a number of reasons (firm size, age of workforce, location, etc.) besides how much cost-insulation they provide. Further, as the excise tax threshold rises slower than health care inflation, it can no longer legitimately be called a tax on high-cost plans, unless the definition of what are high-cost plans is altered to mean all plans.

Why is this still a live question? Various proposals to even further erode the tax-preference for health insurance continue to pop up in the debate over budget deficits. So, it should be pointed out again that the excise tax (or taxing benefits through a tax exclusion cap or the like) is simply “not well targeted” (pg. 10) and does not create the right incentives for the creation of the most efficient insurance policy; in fact, it is a blunt instrument that creates no incentives except to purchase cheaper policies.

In the end, health care cost control should not come about by forcing consumers to figure out what they’re going to sacrifice – our health system just does not provide them the information they need to do this. The rest of the Holahan et al paper describes some better ways to contain costs.

With friends like these…

This past Wednesday on Marketplace, the regulation-and-jobs debate came up again. An NPR segment with two leading economists who have provided cutting-edge research on why many environmental regulations have very high benefit/cost ratios was … both unhelpful and wrong about the current debates regarding regulatory changes.

Rob Stavins argued that the effect on jobs of regulatory changes is second-order and shouldn’t be the driver of public debate. He’s clearly right. Then he said, “This is an area where unfortunately one has to curse both sides of the debate.” The NPR reporter immediately followed: “These aren’t end-of-the-economy-as-we-know-it job destroyers. They aren’t miracle economic growth engines.”

This is maddening. While it’s not clear whether it’s Stavins or the NPR reporter setting up the “crazies on both sides” frame, it is worth pointing out that the anti-regulatory side has indeed routinely made crazy claims about the job-destroying impact of regulations. But, on the pro side, who has claimed that new regulations would be “miracle economic growth engines?” Seriously, who? It’s true that proponents of green-jobs often make some large claims about their potential as economic growth engines – but these are always premised on policy proposals that are much larger than just regulatory changes. I really can’t think of a single analyst or advocate who has claimed that regulatory change alone could serve as a jobs program (ed note – To be clear, by “regulatory change” I mean specifically “adopting new regulations” – the other side’s contention is that doing away with all (or even some) regulations will indeed have a mammoth positive impact on jobs).

Michael Greenstone then argued, “The costs of these regulations are greater in challenging economic times like the current one.”

Again, this is just not right. In fact, when the economy has lots of excess slack and interest rates have run up against the zero-bound and cannot provide any further incentives for firms to borrow and undertake job-creating investments in plant and equipment, then any exogenous policy change that does shake free some plant and equipment investments will create new jobs and provide a boost to the economy. In short, the costs of passing regulations that require firms to make outlays on new investments to comply are lower, not higher, in times like these. In fact, for some rules, the net new jobs created by these investments lead the overall jobs-impact of undertaking them now to be positive.

And how has EPI described the jobs-impact of regulatory changes? In a comprehensive literature survey, John Irons and Isaac Shapiro conclude:

“this review of the studies of regulations in place finds little evidence of significant negative effects on employment. Overall, the picture that emerges from this review is a positive one. For decades, regulations have generally and consistently struck a reasonable balance, with their benefits to health, safety, and well-being far exceeding their costs.”

And, in a comprehensive look at a particular regulatory change, the “air toxics rule,” I wrote:

“The claims of this paper are conservative—the toxics rule is not a jobs program. Instead, it is a regulatory change that generates great benefits at moderate costs and, along the way, will likely create a relatively modest number of jobs.”

This is just not an issue (regulation and jobs) where both sides deserve a pox – one side is being careful and weighing evidence and the other side is just bloviating.

Snapshot: Areas with highest Hispanic unemployment are in Northeast

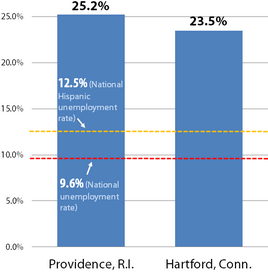

Quick, name the U.S. metropolitan area with the highest unemployment rate among Hispanics. Need a hint? It’s in the Northeast.

This may surprise many of you because when people think of high Hispanic unemployment, they think of metro areas like Las Vegas and Los Angeles. As Algernon Austin, director of EPI’s Race, Ethnicity, and the Economy program, pointed out earlier this week, this assumption is understandable because those areas have both large Hispanic populations and high levels of Hispanic unemployment.

At 25.2 percent, the Providence, R.I., metropolitan area has the highest Hispanic unemployment rate. Another New England metro area, Hartford, Conn., is second with a Hispanic unemployment rate of 23.5 percent. Both areas also had the highest percentage-point increases in Hispanic unemployment from 2009 to 2010; Hartford went up 7.5 percentage points and Providence 4.6. According to 2010 Census data, Providence is 37th and Hartford 39th in Hispanic population in metropolitan areas.

SEE FULL SNAPSHOT: Metropolitan areas with highest rates of Hispanic unemployment

In order, here’s where the five metro areas with the largest Hispanic populations ranked in unemployment:

- Los Angeles: 9th, 13.4 percent

- New York: 23rd, 11.0 percent

- Miami: 12th, 12.8 percent

- Houston: 36th, 8.9 percent

- Riverside, Calif.: 5th, 18.4 percent

For more on this issue, read Austin’s piece Hispanic unemployment highest in Northeast metropolitan areas. And for a companion paper on black metropolitan unemployment, read High black unemployment widespread among nation’s metropolitan areas.

Calculating the cost of war

Today marks 10 years since the commencement of the U.S war against Afghanistan. To date, Congress has appropriated approximately $1.3 trillion dollars to prosecute that conflict along with the war in Iraq. This estimate is consistent across varied sources and is readily available from the Congressional Research Service, but tallying appropriated costs understates the true cost of our war efforts. In a nutshell, these figures do not include the debt service to finance the wars, which for the first time in U.S. history have been not been offset by tax increases. They also do not include war expenses hidden in the Pentagon’s base budget, or the costs of providing medical care and disability benefits for the thousands of veterans permanently injured by fighting abroad.

A group of academics has added it all up and estimates that the cumulative costs of the wars are up to $4 trillion and rising. Staggering though that number may be, what appalls me is that their estimate, the most comprehensive publicly available, is ultimately an unofficial one. There has been no official accounting or independent audit of Iraq and Afghanistan war costs so that taxpayers know exactly what value they have received for their money. Contrast that with the federal government’s accounting of the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act (ARRA), which has an entire website that gives laypersons, policy wonks and researchers customized looks at how virtually every dollar of ARRA funds were allocated and spent. Yet for war costs, already well above what was spent on ARRA, we are forced to rely on unofficial estimates.

This lack of transparency weakens our democracy by not allowing Americans to hold our elected officials accountable for decisions they make to engage in conflict. Rep. John Lewis (D-GA) has introduced The Cost of War Act, a bill that takes only 91 words to direct the Department of Defense to publish, on a public website, the cost of our current wars. The value of such an action—especially if the end result is as robust as Recovery.gov—would be to force this Congress to have an adult conversation about priorities, spending, deficits and debt. Right now, the only sunlight on federal spending shines on the non-defense, discretionary side, which is dwarfed by defense spending–all of which is discretionary. Exposing it all to the same level of scrutiny would lead to better debate among our policymakers.

To be sure, even if there were a definitive, transparent accounting of the financial obligations incurred by the war efforts, we would still not have an understanding of the true costs of war. What might we have used the money on, if not the wars? Imagine what hundreds of billions invested in infrastructure or education would do to reduce unemployment and increase competitiveness. Or, imagine the economic productivity that the more than 6,000 killed would have generated over their lifetimes. These opportunity costs are either difficult or impossible to calculate, but are nonetheless real. But even if the metaphysical costs of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts are too philosophical to consider, it is certainly possible to calculate and publicize the dollars and cents we have spent and continue to spend on our military efforts.

Could currency legislation lead to a trade war? Think again

On Wednesday, Senator Orrin Hatch claimed that the Currency Exchange Rate and Oversight Reform Act of 2011 (S 1619) (the Currency Reform Act) could cause “a huge trade war … with China.” Nothing could be further from the truth. A large share of our exports to China are intermediate products that are used to produce exports to the United States. If China raised tariffs or otherwise restricted imports of those products, it would simply raise the cost of their own exports to the United States. Furthermore, U.S. imports from China exceed our exports to that country by a ratio of more than 4 to 1. So every dollar in tariffs imposed by China would, in theory, be matched by four dollars in U.S. tariffs on their exports, if China ever tried to engage us in a trade war. But history shows us that they will not.

Senator Hatch also disparaged my latest report on China trade and U.S. employment, but I’ll save that argument for another post. We appreciate his use of our research, and are glad that he felt it necessary to respond.

In Aug. 2005, the Senate passed much a much tougher currency bill sponsored by Senators Chuck Schumer and Lindsey Graham (S. 295) that would have imposed a 27.5 percent tariff on all imports from China if it failed to revalue within 180 days. That bill never passed the House and never become law. Nonetheless, shortly after the bill was approved in the Senate (by a veto-proof majority), China began to revalue, for the first time in more than seven years, ultimately allowing the yuan (or RMB) to rise by 18.6 percent over the next three years. China did not retaliate.

China will not retaliate if the Currency Reform Act becomes law because it will hurt its own exporters if it does, and because China will benefit if it does revalue. If the yuan is allowed to appreciate, it will lower the cost of oil, food and other imported commodities in China. This will put downward pressure on inflation, which has been accelerating rapidly in China this year. Lower fuel and food prices will be particularly helpful to low-income families in China, who are very dependent on these basic commodities.

As shown in my most recent report on China trade and U.S. employment (Table 2), some of the most important U.S. exports to China are basic commodities used in producing exports such as chemicals ($11.6 billion, 13.5 percent of total U.S. exports to China), scrap and second hand goods ($8.5 billion, 10.0 percent) and semiconductors ($6.1 billion, 7.1 percent). Agricultural products ($15.4, 18.0 percent) could be vulnerable, but U.S. imports from China, which could be subject to some trade restrictions, were $363.6 billion and exceeded agricultural exports by a ratio of 23:1 in 2010.

When Senator Hatch referred to a “huge trade war,” most people think of the Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930, which raised tariffs on about one-third of U.S. imports to a peak of 59.1 percent. However, average tariff rates rose to only 19.8 percent in 1933. Canada, our largest trading partner retaliated with higher tariffs on about 30 percent of U.S. imports, and Germany developed a system of autarky (little or no trade).

The Currency Reform Act of 2011 would not impose sweeping, across-the-board tariff increases (as did the Smoot-Hawley Act). It defines a new process for determining which currencies are “fundamentally misaligned,” and defines new procedures for conducting negotiations with such countries including new consequences, especially when a country persistently fails to revalue despite continuing negotiations. These measures are intended to spur negotiated solutions to currency manipulation, not to spark a trade war.

The Currency Reform Act also authorizes the Commerce department to take currency manipulation into account in anti-dumping and countervailing duty investigations. But these changes will affect a small share of total U.S. trade with currency manipulators. Again, there is nothing similar in these proposals to the broad, across-the-board tariffs imposed in the Smoot-Hawley act.

“Trade war” is a term that is easily thrown around in legislative debate and by political commentators. As Fred Bergsten has noted, China’s currency manipulation “is by far the largest protectionist measure adopted by any country since the Second World War – and probably in all of history.” The Currency Reform Act is a measured response designed to bring about a negotiated end to China’s predatory economic policies. China has launched a trade war on the rest of the world. It is important to stand up to the bully, to restore balance to the global trading system and world demand.

The teacher gap

Over the last three years, state and local government employment has dropped by 641,000 as state and local budgets have been squeezed as a result of the recession. With kids heading back to the classroom this fall, it’s worth considering how much of that drop has hit public schools.

Of the decline in state and local government jobs over the last three years, close to half (278,000) was in local government education, which is largely jobs in public K-12 education (the majority of which are teachers but also includes teacher aides, librarians, guidance counselors, administrators, support staff, etc). On the other hand, over the same period, public K-12 enrollment increased by 0.6 percent (using the actual and projected enrollment growth rates found in Table 1 here). Just to keep up with this growth in the student population, employment in local public education should have grown at roughly the same rate, which would have meant adding around 48,000 jobs. Putting these numbers together (i.e., what was lost plus what should have been added to keep up with the expanding student population) means that the total jobs gap in local public education as a result of the Great Recession and its aftermath is around 326,000.

This decline means not only larger class sizes, but also fewer teacher aides, fewer extra-curricular activities and a narrower curriculum for our children. Furthermore, this number almost surely understates the real gap. Between 2008 to 2010, the number of children living in poverty increased by 2.3 million, and is likely even higher today. Increased child poverty increases the need for services provided through schools. Instead, public schools have fewer personnel and fewer resources to educate more students, and more students with greater needs.

Quick Take: Miserably low job growth

The unemployment rate is for the moment holding steady at 9.1 percent, but at the current rate of job creation, the unemployment rate will soon begin to rise again. We are mired in high unemployment with miserably low job growth. This country has 14 million unemployed people, and the job growth rate has unmistakably slowed down since the spring.

This morning’s data release shows that 103,000 jobs were added in September. That number, however, includes around 45,000 Verizon workers coming off the picket lines, so the net new jobs the economy created in September was actually around 58,000. This level of growth is in line with the dismal average of the last four months, which was 64,000, and that was a slowdown from the not-doing-much-more-than-keeping-up-with-population-growth average of 123,000 of the prior 14 months.

The H-2B guestworker program puts downward pressure on American wages

This past January, the Department of Labor (DOL) published a final rule establishing a new wage methodology for determining the appropriate wages to be paid to guestworkers in the “H-2B” program—a temporary immigrant guestworker category intended to help employers fill labor shortages. Among other things, U.S. law and regulation require that H-2B workers only be authorized to enter and work in the United States if the H-2B worker’s employment will not be “adversely affecting the wages” of United States workers. The DOL’s new rule will require that H-2B workers receive the average wage paid to all workers in the same occupation and geographical region in order to prevent downward pressure on the wages of U.S. workers. But for now, the rule’s implementation has been delayed—and a lobbying firestorm by businesses and members of Congress, led by Senator Barbara Mikulski from Maryland—has put its survival in doubt.

The chart below shows the difference between the hourly rate that H-2B crab pickers and landscape workers are currently paid in Maryland under the old (and still current) rule, and the statewide average for all workers in the given occupation, which is what workers should be paid in order to prevent wages from being depressed for U.S. workers. H-2B crab pickers and landscapers are underpaid by $4.82 and $3.35 per hour, respectively.

These data suggest that employers have been using the H-2B program as a way to degrade the wages of U.S. workers. H-2B crab pickers in Maryland (i.e., workers who literally pick the meat out of a crab, like this), who fall under the occupational category of “Meat, Poultry, and Fish Cutters and Trimmers” above, are paid the federal minimum wage ($7.25), when the state-wide average is $12.07 per hour.

Another way to look at this is that a crab picker earning the state average will earn $25,105 over the course of a year, which is above the poverty line for a family of four ($22,113). But current H-2B crab pickers only earn $15,080 a year—which is about $7,000 below the poverty line. For landscapers in Maryland, the results are similar—in both cases the increase in hourly wage will literally lift the H-2B worker out of poverty.

You can read more about the H-2B program and the Labor Department’s wage rule in my new extended commentary, H-2B employers and their congressional allies are fighting hard to keep wages low for immigrant and American workers.

So’s your mother. And Reagan. And you’ve never run a business!

A few days ago, Paul Krugman noted the evidence-free “rebuttal” offered up by the American Enterprise Institute to Larry Mishel’s takedown of the “regulation is what’s holding back recovery” argument. The title of Krugman’s post -“So’s your mother. And Reagan” – captured the useful content of what I generally hear from those engaged in hand-waving about “job-killing regulations.”

On Tuesday, though, I got to hear another argument from Peter Schiff on John Stossel’s show. I was making the case that it’s hard to see how regulation is driving up costs and robbing firms of profitability given that profit margins (unit profits as a share of total costs) were at their highest levels in either 42 or 45 years (depending on whether you looked at pre- or post-tax rates*). And, as Brookings’ Gary Burtless has pointed out, if you’re profitable now and fearful of future regulations, then you’d be doing everything you can to produce goods and services for sale now rather than later; we should see strong employment growth in the short-term.

Now, what would keep firms that were making record profits on each unit shipped from deciding to ship even more units and hire more workers to do so? A shortfall of demand (i.e., not enough customers) maybe?

Hearing this argument, Schiff made a careful, empirically-based case for why I was wrong started sneering that I had never run a business. It’s true, I haven’t. But I can look at data.

—

*The data came from Table 1.1.15 of the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) from the Bureau of Economic Analysis – Price, Costs, and Profit Per Unit of Real Gross Value Added of Nonfinancial Domestic Corporate Business.

China’s People’s Bank: The lady doth protest too much

On Monday, the Senate agreed to move ahead with debate on the China currency bill, approving a petition to proceed on the measure by a 79-19 margin; this morning they voted to proceed to a final vote, also by a strong margin. Predictably, the People’s Bank of China responded by claiming that the yuan (or RMB) has appreciated “greatly” and is close to a balanced level. The best indicator that China is manipulating its currency is simply that it must buy hundreds of billions of dollar in U.S. assets each year to keep it from moving ever higher. That’s how we know that they haven’t done enough.

China’s purchases of Treasury bills and other types of foreign exchange reserves have accelerated in the past year, as I showed on Monday. In the past 12 months (ending June 30, 2011), they acquired nearly $730 billion in additional reserves. Between 2005 and 2010 their reserve acquisitions averaged between $400 and $450 billion, which indicates that the yuan is even more undervalued than it was a year ago. This is true despite the yuan’s real, inflation-adjusted appreciation of 7.4 percent in the past year.

William R. Cline and John Williamson of the Peterson Institute have produced some of the best estimates of China’s currency manipulation. In a series of annual reports on fundamental equilibrium exchange rates (FEERs), they have estimated that China’s currency manipulation increased from 24.2 percent in 2010 to 28.5 percent in 2011, despite the fact that China’s real exchange rate appreciated over the past year. Three factors explain why China’s estimated FEERs increased in 2011.

First, the International Monetary Fund has estimated that China’s global current account surplus (the broadest measure of its trade balance) will more than double from $305 billion in 2010 to $852 billion in 2016 (an increase of 179 percent), as shown in the graph below. There is widespread agreement among the G-20 leaders (including China) that global trade flows must be rebalanced to help end mass unemployment around the world. These IMF predictions show that unless China sharply revalues, world trade flows will become even more distorted than they are today. Among the top five currency manipulators identified by Cline and Williamson (China, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan), China is responsible for the vast majority (83 percent) of the estimated global surpluses of these currency manipulators in 2016.

Second, the IMF predicts that China’s current account surplus will rise from 5.2 percent of GDP in 2011 to 7.2 percent in 2016. Cline and Williamson project in their latest research China’s that current account will rise even faster, to 7.8 percent of GDP in 2016. China’s rapidly growing GDP, combined with a rapidly growing trade surplus as a share of its GDP, and its stubborn addiction to currency manipulation will, if unchallenged, destabilize both the U.S. and global recoveries, as suggested by the IMF’s own forecast of global trade imbalances shown above.

The final nail in the case against the People’s Bank is its own massive and growing accumulation of foreign exchange reserves, as noted above. China has invested trillions of dollars to prevent the appreciation of their currency to a fair market value. China’s currency manipulation is a fundamental threat to the U.S. and world manufacturing system. It artificially suppresses the value of the yuan, subsidizing China’s exports to the United States and raising the cost of U.S. exports – both to China and to every country where U.S. exports compete with Chinese products. Enough is enough. It’s time to get tough with China and other currency manipulators.

Progressive counter-pressure for the Fed?

The Occupy Wall Street (OWS) protests have been spreading. In Chicago, protestors have gathered around the Chicago Federal Reserve Bank. Again, the protestors seem to have chosen an awfully good symbolic venue – over the past two years, the Fed has been under ferocious political attack from conservative politicians who want them to stop trying to reduce unemployment with monetary policy. If the Occupy Chicago protests provide counter-pressure from more progressive perspectives, this would be a great thing.*

We’ve already noted the letter from four GOP leaders to Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke last month demanding that he declare surrender in trying to help the faltering economy. This is just the latest in what has been a pretty remarkable effort by conservative politicians to stop the Fed from trying to boost the economy and to convince it to fret about the phantom danger of inflation.

It’s pretty telling that the best that prominent Democratic politicians have managed in response is some hand-wringing that such criticisms threaten the sanctity of central bank independence – essentially demanding that the GOP “leave Ben Bernanke alooooone!”

However, as Mike Konczal notes, even in the best of times, central bank independence as practiced by the Fed should hardly be a prime progressive demand. The Fed’s Open Market Committee – the body that sets the monetary policy direction of the economy – contains 12 slots. Seven of them are for Fed Governors (there are currently 2 vacancies on the Board of Governors), who are generally either economists or policymakers with some expertise in issues the Fed confronts. But five are set aside for presidents of the Fed’s regional reserve banks. These presidents are picked by the board of directors for each regional bank – and these boards are comprised of financial-sector (commercial bank) executives. Essentially, the finance sector gets to pick 5 of the 12 voting members of the FOMC. If one thinks that the interests of the financial sector are not necessarily the same as those of, say, unemployed workers (and I think they’re not) – perhaps the financial sector is more scared of inflation and less scared of unemployment – then central bank “independence” should probably be treated as less sacrosanct than it currently is in D.C.

Imagine, for example, that somebody demanded that the AFL-CIO get 5 voting slots on the FOMC. That would, of course, be considered absolutely crazy by those determined to preserve central bank independence as a principle (i.e., the vast majority of professional policymakers and analysts inside the Beltway). Of course, in practice, this would mean an FOMC that tried much, much harder to fight unemployment than the one we currently have, so crazy sounds pretty good to me.

Worse, this ingrained deflationary bias of the Fed is being reinforced in the current crisis by conservatives who want to abandon all the policy measures (fiscal, monetary and exchange-rate) that could actually help reduce joblessness. Some lonely (and admirable) voices calling on the Fed to do more are out there, but they’re few and far between (and sometimes working for the Bank of England, instead of the Fed).

Finally, however, there seems to be a little pushback. Besides Occupy Chicago, Massachusetss Representative Barney Frank wants to take away the voting power of the five rotating regional banks and replace them with political appointees that must be approved by the Senate. Given that the political appointees of the current Fed have consistently shown more concern over unemployment than their regional bank colleagues, this would be a good (if small) first step to privileging democracy over Fed “independence.”

—

*It’s true that the president of the Chicago Fed has been admirably aggressive in calling for more Fed action to reduce unemployment, especially relative to his other regional bank presidents. So, maybe protests can follow in Dallas, Minneapolis, and Philadelphia?

Eric Cantor cares about poverty?

Via Roberton Williams over at TaxVox, I see that House Majority Leader Eric Cantor has a surprising objection to President Obama’s American Jobs Act (AJA) and its pay-fors: it will hurt soup kitchens and Americans living in poverty. How? By taxing upper-income individuals, of course. Thank goodness compassionate conservatism isn’t dead.