Right-To-Work Laws: Designed To Hurt Unions and Lower Wages

The fact that unions are responsible for workplace benefits, higher wages, and the right to overtime pay is the very reason Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker, the Koch Bothers, and other corporate interests hate them. Walker hates unions so much he compared them to ISIL terrorists, so it’s no wonder that he and Wisconsin’s Republican legislature are rushing through a “right-to-work” (RTW) bill.

RTW laws were originally designed by business groups in the 1940s to reduce union strength and finances, and over the years they’ve been successful. As Melanie Trotman of the Wall Street Journal pointed out to me this morning, none of the 10 states with the highest rates of unionization are right-to-work. The Illinois Economic Policy Institute calculates that RTW reduces union coverage by 9.6 percentage points, on average. Unsurprisingly, weakening unions leads to lower wages and salaries for union and non-union workers alike. Heidi Shierholz and Elise Gould showed that RTW is associated with a $1,500 reduction in annualized wages, on average, even when the analysis takes into account lower prices in those states. (On average, wages in RTW states are nearly $6,000 less.)

Nevertheless, RTW supporters look at the very recent experience of Michigan and Indiana, which passed RTW laws in 2013 and 2012, respectively, to argue that RTW doesn’t inevitably lead to wage reductions. It’s a misguided argument, since no critic claims that the effects of RTW are immediate: It takes a little time for RTW to reduce dues collections, weaken union finances, undermine organizing, and weaken the bargaining position of workers. The law hasn’t even begun to apply to many contracts in Michigan.

New Data Add Fuel to Arguments Against the Trans-Pacific Partnership

In December I showed that growing trans-Pacific trade deficits would set the stage for growing trade-related job displacement. New data released this month show that the U.S. trade deficit with the countries in the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) increased to an unexpectedly large $265.1 billion in 2014, as shown in the updated graph, below. This increase is further proof that U.S. workers don’t need another job-killing trade deal, which would undoubtedly grow the trade deficit even more.

In addition, new developments are likely to increase opposition to the deal being crafted behind closed doors by negotiators from the United States and 11 other countries. In a remarkable op-ed in the Washington Post, Senator Elizabeth Warren identifies a key way in which the proposed TPP is a dangerous and unnecessary corporate giveaway. The TPP would create special tribunals, or dispute resolution panels, that would allow corporations and foreign investors (but not public interest groups or unions) to challenge U.S. laws “without ever setting foot in a U.S. court.” These deals give corporations special rights to force countries to roll back critical regulations. Right now, for example, Philip Morris is using the process to try force Uruguay to halt new anti-smoking regulations that are designed to improve public health. As Warren concludes, if these dispute panels are included in the final TPP, the only winners will be giant, multinational corporations.

The TPP would also do nothing to combat currency manipulation, which is a major driver of U.S. trade deficits with TPP countries including Japan, Malaysia, and Singapore. Ending currency manipulation could reduce U.S. trade deficits and increase GDP—creating between 2.3 to 5.8 million jobs—but U.S. Trade Representative Froman has said that it has not been discussed in TPP negotiations.

It’s increasingly clear that the TPP, like past trade and investment deals, would be a bad deal for U.S. workers. The president should not try to push this deal through, and Congress should not approve it.

Don’t Be Fooled by the Rise in Real Wages in January

The Bureau of Labor Statistics released Real Earnings for January 2015 today, which lets us look at trends in real (inflation adjusted) wages over the month and year. We shouldn’t be fooled by month-to-month changes in the real hourly earnings series. According to the report, real hourly wages for private nonfarm employees rose 1.2 percent between December 2014 and January 2015, but the series is volatile so we should not read too much into one month trends. Furthermore, month-to-month inflation fell 0.7 percent, which should put those inflation adjusted earnings series into perspective.

Meanwhile, real wages grew 2.4 percent over the year (between January 2014 and January 2015). While on its surface, this bump up may seem like a positive sign, this higher-than-trend number is largely due to deflation over the year, as the CPI-U, or Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers, fell 0.2 percent.

Taken another way, wages unadjusted for inflation (i.e., nominal wages) grew 2.2 percent over the year, very much in line with what we’ve seen for the last five years. You can see from the figure below—pulled from EPI’s nominal wage tracker—that nominal wages have been growing around 2.0 percent a year since 2010. January’s rise in nominal wages is not out of line with this trend.

To the policymakers at the Federal Reserve, nominal wage growth should be 3.5-4.0 percent—consistent with inflation plus productivity growth. Given this, it is clear that the Federal Reserve should not take action to slow the economy down. In fact, the labor market and the economy could withstand wage growth even higher than 4 percent, because while profits are still at record highs, labor’s share of corporate sector income has yet to rise in this recovery.

Nominal wage growth has been far below target in the recovery: Year-over-year change in private-sector nominal average hourly earnings, 2007–2015

| All nonfarm employees | Production/nonsupervisory workers | |

|---|---|---|

| Mar-2007 | 3.6427146% | 4.1112455% |

| Apr-2007 | 3.3234127% | 3.8461538% |

| May-2007 | 3.7257824% | 4.1441441% |

| Jun-2007 | 3.8575668% | 4.1267943% |

| Jul-2007 | 3.4482759% | 4.0524434% |

| Aug-2007 | 3.5433071% | 4.0404040% |

| Sep-2007 | 3.2337090% | 4.1493776% |

| Oct-2007 | 3.2778865% | 3.7780401% |

| Nov-2007 | 3.3203125% | 3.8869258% |

| Dec-2007 | 3.1113272% | 3.8123167% |

| Jan-2008 | 3.1067961% | 3.8619075% |

| Feb-2008 | 3.0464217% | 3.7296037% |

| Mar-2008 | 3.0332210% | 3.7746806% |

| Apr-2008 | 2.8324532% | 3.7037037% |

| May-2008 | 3.0172414% | 3.6908881% |

| Jun-2008 | 2.6666667% | 3.6186100% |

| Jul-2008 | 3.0000000% | 3.7227950% |

| Aug-2008 | 3.2794677% | 3.8263849% |

| Sep-2008 | 3.2747983% | 3.6425726% |

| Oct-2008 | 3.3159640% | 3.9249147% |

| Nov-2008 | 3.5916824% | 3.8548753% |

| Dec-2008 | 3.6303630% | 3.8418079% |

| Jan-2009 | 3.5310734% | 3.7183099% |

| Feb-2009 | 3.4725481% | 3.6516854% |

| Mar-2009 | 3.1775701% | 3.5254617% |

| Apr-2009 | 3.2212885% | 3.2924107% |

| May-2009 | 2.8358903% | 3.0589544% |

| Jun-2009 | 2.7365492% | 2.9379157% |

| Jul-2009 | 2.5889968% | 2.7056875% |

| Aug-2009 | 2.4390244% | 2.6402640% |

| Sep-2009 | 2.2977941% | 2.7457441% |

| Oct-2009 | 2.3383769% | 2.6272578% |

| Nov-2009 | 2.0529197% | 2.6746725% |

| Dec-2009 | 1.8198362% | 2.5027203% |

| Jan-2010 | 1.9554343% | 2.6072787% |

| Feb-2010 | 1.8140590% | 2.4932249% |

| Mar-2010 | 1.7663043% | 2.2702703% |

| Apr-2010 | 1.7639077% | 2.4311183% |

| May-2010 | 1.8987342% | 2.5903940% |

| Jun-2010 | 1.7607223% | 2.4771136% |

| Jul-2010 | 1.8476791% | 2.4731183% |

| Aug-2010 | 1.7070979% | 2.4115756% |

| Sep-2010 | 1.8867925% | 2.2447889% |

| Oct-2010 | 1.8817204% | 2.5066667% |

| Nov-2010 | 1.6540009% | 2.1796917% |

| Dec-2010 | 1.7426273% | 2.0169851% |

| Jan-2011 | 1.9625335% | 2.2233986% |

| Feb-2011 | 1.8262806% | 2.1152829% |

| Mar-2011 | 1.8246551% | 2.1141649% |

| Apr-2011 | 1.9111111% | 2.1097046% |

| May-2011 | 2.0408163% | 2.1041557% |

| Jun-2011 | 2.1295475% | 2.0493957% |

| Jul-2011 | 2.2566372% | 2.2560336% |

| Aug-2011 | 1.9434629% | 1.9884877% |

| Sep-2011 | 1.9400353% | 1.9864088% |

| Oct-2011 | 2.1108179% | 1.7169615% |

| Nov-2011 | 2.0228672% | 1.8210198% |

| Dec-2011 | 1.9762846% | 1.8210198% |

| Jan-2012 | 1.7060367% | 1.3982393% |

| Feb-2012 | 1.9247594% | 1.5018125% |

| Mar-2012 | 2.1416084% | 1.7080745% |

| Apr-2012 | 2.0497165% | 1.7561983% |

| May-2012 | 1.7826087% | 1.4425554% |

| Jun-2012 | 1.9548219% | 1.5447992% |

| Jul-2012 | 1.7741238% | 1.3853258% |

| Aug-2012 | 1.8630849% | 1.3340174% |

| Sep-2012 | 1.9896194% | 1.3839057% |

| Oct-2012 | 1.4642550% | 1.2787724% |

| Nov-2012 | 1.8965517% | 1.4307614% |

| Dec-2012 | 2.1102498% | 1.6351559% |

| Jan-2013 | 2.1505376% | 1.8896834% |

| Feb-2013 | 2.1030043% | 2.0408163% |

| Mar-2013 | 1.8827557% | 1.8829517% |

| Apr-2013 | 1.9658120% | 1.7258883% |

| May-2013 | 2.0504058% | 1.8791265% |

| Jun-2013 | 2.1729868% | 2.0283976% |

| Jul-2013 | 1.9132653% | 1.9736842% |

| Aug-2013 | 2.2118248% | 2.1265823% |

| Sep-2013 | 2.0356234% | 2.1739130% |

| Oct-2013 | 2.2495756% | 2.2727273% |

| Nov-2013 | 2.1573604% | 2.2670025% |

| Dec-2013 | 1.9401097% | 2.3127200% |

| Jan-2014 | 1.9789474% | 2.2055138% |

| Feb-2014 | 2.1017234% | 2.4500000% |

| Mar-2014 | 2.1419572% | 2.2977023% |

| Apr-2014 | 1.9698240% | 2.2954092% |

| May-2014 | 2.0510674% | 2.3928215% |

| Jun-2014 | 1.9599666% | 2.2862823% |

| Jul-2014 | 2.0442219% | 2.2828784% |

| Aug-2014 | 2.1223471% | 2.4789291% |

| Sep-2014 | 1.9950125% | 2.2761009% |

| Oct-2014 | 1.9510170% | 2.2222222% |

| Nov-2014 | 1.9461698% | 2.1674877% |

| Dec-2014 | 1.6549441% | 1.6216216% |

| Jan-2015 | 2.1982742% | 1.9607843% |

* Nominal wage growth consistent with the Federal Reserve Board's 2 percent inflation target, 1.5 percent productivity growth, and a stable labor share of income.

Source: EPI analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Employment Statistics public data series

Obama Has Options on Immigration: Litigation Will Delay Executive Actions, But Won’t Stop Them

Twenty-six states, led by Texas, have convinced federal district court Judge Andrew Hanen to temporarily enjoin two important executive immigration actions—DAPA and the expansion of DACA—which President Obama announced in November of last year. DAPA is the “Deferred Action for Parental Accountability” initiative, which would grant a temporary reprieve from deportation, along with work authorization (known as an employment authorization document or “EAD”) for up to 3.7 million unauthorized immigrants if they have been present in the United States since 2010, are not an enforcement priority, and are the parent of a child who is a U.S. citizen or legal permanent resident. DACA is “Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals,” announced in 2012, which grants similar relief from deportation and an EAD, but was created to protect younger unauthorized immigrants who entered the United States as minors. The original version of DACA from 2012 is not at issue in the litigation—only the expansion of DACA announced by the president, which could cover an estimated additional 300,000 persons.

I do not believe the 26 states will win on the merits of the case—either in the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals or at the U.S. Supreme Court—and thereby end DAPA or expanded DACA, though some scholars and lawyers are arguing that they will. But it’s important to be clear about what Judge Hanen’s ruling means exactly. First, he ruled that states like Texas were likely to be harmed by the DAPA and expanded DACA initiatives because of the costs imposed on states by federal requirements when states issue driver’s licenses to unauthorized immigrants. Because of this potential harm, which could be redressed by the court ruling to stop DAPA/expanded DACA, Judge Hanen reasoned the states had standing to sue the government. Then, his legal reasoning justifying the injunction—which halts DAPA and expanded DACA while the merits of the case are litigated—was based on the states’ complaint that the government failed to comply with certain procedural rules in the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) when creating DAPA/expanded DACA. Because Judge Hanen believes the states are likely to win on their APA claim, he halted the government’s future implementation of DAPA and expanded DACA.

Judge Hanen’s opinion does not enjoin the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) immigration enforcement priorities or other executive immigration actions announced on November 20, 2014. Only the affirmative application process for deferred action under DAPA and expanded DACA are temporarily halted from getting underway. Yet even if the states ultimately prevail on the merits of their claims, it will only be a temporary victory, because the president has alternative means available to him that are legal and would achieve all or most of the goals of his DACA and expanded DACA initiatives. Read more

Wages Stagnated or Fell Across the Board in 2014—With One Notable Exception

Yesterday, I released a report that looked at the most recent reliable data on Americans’ wages—by decile and by educational attainment, through 2014. These data are illuminating, because they let us look beneath the hood on the overall wage story, going beyond the topline trends that are usually covered by the media.

The recovery has entered a period of solid job growth. That good news shouldn’t be overstated—if we continue to see 2014’s average rate of job growth, it will still be 2017 before we return to pre-recession labor market health—but the economy has been adding jobs at a respectable clip. However, decent wage growth has yet to be seen.

From 2013 to 2014, real, inflation-adjusted hourly wages stagnated or fell across the board, with one notable, revealing exception.

Let’s start at the top of the wage distribution: those workers with the most education and the highest wages. Over the last year, real wages at the top of the wage distribution fell—by 0.7 percent at the 90th percentile and 1.0 percent at the 95th percentile. Real wages fell for workers with a 4-year college degree—a drop of 1.3 percent—and even more for those workers with an advanced degree—a decline of 2.2 percent. This sends a clear message: If even these groups of highly educated workers facing the lowest rates of unemployment are seeing outright wage declines, there is clearly lots of slack left in the American labor market, and policymakers—particularly the Federal Reserve—should not try to slow the recovery down in an effort to keep wage and price inflation in check. They’re both already firmly in check even for the most privileged workers.

A Glimmer of Positive News: Wages Rose for Bottom 10 Percent (Unlike for Everybody Else)

This post originally appeared on TalkPoverty.org.

In a report released this week, I found that 2014 continued a 35-year trend of broad-based wage stagnation.

Real, inflation-adjusted hourly wages stagnated or fell across the board, with one notable, glimmer of positive news: Unlike the rest of the wage distribution, wages actually increased at the 10th percentile between 2013 and 2014.

The figure below shows changes in real hourly wages throughout the wage distribution between 2013 and 2014. What is particularly striking is that almost every decile and the 95th percentile experienced real wage declines from 2013 to 2014, with two exceptions. First, there was a very small increase at the 40th percentile wage, up 3 cents, or 0.3 percent. But a more economically significant increase occurred at the 10th percentile where hourly wages were up 11 cents, or 1.3 percent.

So, why did wages at the bottom tick up when they fell for nearly everyone else? What is so special about that wage that sits below 90 percent and above 10 percent of workers (i.e., is not generally earned by particularly privileged workers)?

Percent change in real hourly wages, by wage percentile, 2013–2014

| Percent change, 2013–2014 | |

|---|---|

| 10th | 1.30049% |

| 20th | -0.67228% |

| 30th | -0.42556% |

| 40th | 0.25237% |

| 50th | -0.43183% |

| 60th | -0.74864% |

| 70th | -0.84497% |

| 80th | -1.02100% |

| 90th | -0.65219% |

| 95th | -0.98396% |

Note: The xth-percentile wage is the wage at which x% of wage earners earn less and (100-x)% earn more.

Source: EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata

Designed to Deceive: President’s Economic Report on Trade and Globalization

The 69th Economic Report of the President (ERP), released this week, has much to recommend it—especially its focus on policies needed to rebuild middle-class economics, including raising the federal minimum wage and increasing job-creating investments in infrastructure, science, and technology. However, the report runs off the road when it turns to trade. The official summary of the report features a chart on trade which claims that “export intensive industries report 17 percent higher average wages than non-export intensive industries.” As I pointed out in a recent blog post on trade and wages, this frequently repeated claim is less than half the story. Wages in import-competing industries (not shown in the ERP chart) are also much higher than in non-traded industries, and also substantially higher than the jobs supported by exports. Worse yet, growing trade deficits have eliminated many more good jobs in import competing industries than are supported by exports. So, on balance, U.S. trade has eliminated many more good jobs than are supported in exporting industries. For middle-class working Americans, trade and globalization has indeed caused a race to the bottom in jobs and wages.

As I’ve written before, a good illustration is provided by U.S. trade with China, which was responsible for nearly half (46.5 percent) of our $736.8 billion goods trade deficit in 2014. Jobs in industries exporting to China did pay well in 2009–2011 (the last years for which we have complete wage data)—an average of $872.89 per week, or 10.3 percent more than workers making non-traded goods and services (who earned only $791.14 per week), as shown in the figure below. However, workers in import-competing industries were paid even better—an average of $1,021.66 per week, or 29.1 percent more than workers in non-traded industries.

Average weekly wages* in different industries affected by U.S. trade with China

| Average weekly wages* | |

|---|---|

| Non–traded industries | $791 |

| Export Industries | $873 |

| Import Industries | $1,022 |

* Average wages by education group are from a 3-year pooled sample of workers by industry from 2009–2011.

Source: Author's analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata

Examined in isolation, jobs in industries supported by exports look good (at least when they are compared to jobs in non-traded industries). But those jobs come at a huge price to workers displaced by imports, and to all workers forced to compete with the growing surge of imports from low-wage countries.

New Data Show How Firms Like Infosys and Tata Abuse the H-1B Program

Outsourcing by the thousands

The outsourcing companies involved in the Southern California Edison (SCE) scandal I wrote about last week—where U.S. workers were replaced with H-1B guestworkers—are Infosys and Tata Consultancy Services. These two India-based IT firms specialize in outsourcing and offshoring, are major publicly traded companies with a combined market value of about $115 billion, and are the top two H-1B employers in the United States. In Fiscal Year (FY) 2013, Infosys ranked first with 6,269 H-1B petitions approved by the government, and Tata ranked second with 6,193. As with the SCE scandal, these leading offshore outsourcing firms use the H-1B program to replace American workers and to facilitate the offshoring of American jobs. Because of this, it’s likely that Americans lost more than 12,000 jobs to H-1B workers in just one year. FY13 H-1B data I’ve analyzed, acquired through a Freedom of Information Act request, reveals new details about how firms like Infosys and Tata are using the H-1B nonimmigrant visa program. Spoiler alert: they don’t use the H-1B visa as a way to alleviate a shortage of STEM-educated U.S. workers; they use it primarily to cut labor costs. But the other main arguments proffered to support an expansion of the H-1B program are easily debunked with even a cursory look at the H-1B data.

Lower wages

The principal reason that firms use H-1Bs to replace American workers is because H-1B nonimmigrant workers are much cheaper than locally recruited and hired U.S. workers. As Table 1 shows, Infosys and Tata pay very low wages to their H-1B workers. The average wage for an H-1B employee at Infosys in FY13 was $70,882 and for Tata it was $65,565. Compare this to the average wage of a Computer Systems Analyst in Rosemead, CA (where SCE is located), which is $91,990 (according to the U.S. Department of Labor). That means Infosys and Tata save well over $20,000 per worker per year, by hiring an H-1B instead of a local U.S. worker earning the average wage. But at SCE specifically, the wage savings are much greater. SCE recently commissioned a consulting firm, Aon-Hewitt, to conduct a compensation study, which showed that SCE’s IT specialists were earning an average annual base pay of $110,446. That means Tata and Infosys are getting a 36 to 41 percent savings on labor costs—or saving about $40,000 to $45,000 per worker per year.

Below Average Wages for Infosys and Tata's H-1B Workers Compared to SCE Employees and Local Average Wage (FY13)

| H-1B Rank | Firm | New H-1Bs Received | Median Wage | Average Wage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Infosys | 6,269 | $65,631 | $70,882 |

| 2 | Tata Consultancy Services | 6,163 | $65,500 | $65,565 |

| Annual Wages for Computer Systems Analyst in Los Angeles CA (where SCE is Headquartered) | $90,376 | $91,990 | ||

| SCE Workers: Average Base Pay for IT Specialists/Engineers (2013) | $110,466 | |||

An Open Letter to Sec. of Labor Tom Perez

An open letter to Secretary of Labor Tom Perez and Wage and Hour Administrator David Weil

Dear Mr. Secretary:

Several newspapers and journals, including Computerworld and the L.A. Times, have reported that Southern California Edison (SCE), a public utility, has laid off hundreds of its U.S. employees and replaced them with H-1B guestworkers employed by the India-based IT services firms Infosys and Tata Consultancy Services. As my colleague, Ron Hira, has written, “Adding to the injustice, American workers losing their jobs are being forced to do “knowledge transfers,” an ugly euphemism that means being forced to train your own foreign replacement.”

As you know, the law (the Immigration and Nationality Act) forbids the hiring of H-1B temporary foreign guestworkers whose employment would “adversely affect the wages and working conditions of U.S. workers comparably employed.” Clearly, taking away the jobs, wages and benefits of the laid-off SCE employees does adversely affect their wages and working conditions.

You have authority under the Immigration and Nationality Act to investigate this case, but I have seen no announcement that you intend to do so or that you share my sense of outrage that the H-1B program is being abused in such an egregious way. I hope that we will soon learn that the Department of Labor intends to investigate and remedy this harm to skilled U.S. workers who have pursued education and training in a technical field, worked hard, and played by the rules. Our government should, at the very least, ensure that its programs, including its visa programs, are not used to destroy the careers and financial security of its people.

Sincerely,

Ross Eisenbrey

Vice President

Economic Policy Institute

Wage Theft by Employers is Costing U.S. Workers Billions of Dollars a Year

Rampant wage theft in the United States is a huge problem for struggling workers. Surveys reveal that the underpayment of owed wages can reduce affected workers’ income by 50 percent or more. Most recently, a careful study of minimum wage violations in New York and California in 2011 commissioned by the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) determined that the affected employees’ lost weekly wages averaged 37–49 percent of their income. This wage theft drove between 15,000 and 67,000 families below the poverty line. Another 50,000–100,000 already impoverished families were driven deeper into poverty.

The extensive weekly minimum wage violations uncovered by the DOL study in California and New York alone amount to an estimated $1.6 billion–$2.5 billion over the course of a full year. Given that the combined population of California and New York is 18.5 percent of the U.S. total, it is reasonable to estimate that minimum wage violations nationwide amount to at least $8.6 billion a year, and as much as $13.8 billion a year. On the one hand, violations in these two states might be less frequent because the wage and hour enforcement effort in New York and California is greater than in most states and violations might be deterred (Florida, for example, does not have a state labor department). But on the other hand, their large immigrant populations might increase the prevalence of wage theft—the DOL study found that non-citizens were 1.6 to 3.1 times more likely to suffer from a minimum wage violation.

The DOL study vastly understates the total impact of wage theft because it reported only on minimum wage violations, which are more frequent than overtime violations but usually involve smaller per violation dollar amounts than many overtime pay violations. A bookkeeper, for example, earning an annual salary of $45,000, who works 10 hours of unpaid overtime a week might lose $325, whereas a minimum wage worker forced to work “off-the-clock” unpaid for 10 hours would lose “only” $72.50, or ten times the state minimum wage if it were higher than the federal minimum. (Overtime violations are very frequent among low wage workers: a 2009 study found that on a weekly basis, 19 percent of front-line workers in low wage industries were cheated out of overtime pay to which they were entitled.)

DOL’s new study shows the need for much greater efforts to ensure employer compliance. Helpfully, the president has called for increases in the budget and staffing of the Wage and Hour Division, but Congress should revisit the obsolete penalties for non-compliance: repeated or willful violations of the minimum wage and overtime requirements are subject to a maximum fine of only $1,100.

A Milestone Week for Apple’s Stock, but Not its Workers

This week was a milestone for Apple. As its stock continues to rise, its market cap exceeded $700 billion—the largest valuation ever achieved by any U.S. company. This milestone, however, must be viewed with considerably less admiration after one takes a close look at its new “supplier responsibility” report. The report reveals important information about one of the less appetizing ingredients of Apple’s vast success: the continued mistreatment of the workers who make its products. The report shows that widespread labor rights violations can still be found in Apple’s massive supply chain, and that Apple continues to obfuscate these realities in its public communications on the subject.

Apple fails to report that its own data shows that labor practices are getting worse in several important areas. In its new report, which covers 2014, Apple says that in 92 percent of cases, the workweeks of the employees in its supply chain fell below its 60 hours per week standard. Apple fails to report that this compliance rate is down from the 2013 compliance rate of 95 percent. In 2014, Apple found that the overall labor rights compliance rate in the area of Health and Safety was 70 percent; it fails to state that this is down from the 2013 compliance rate of 77 percent. Notably, while Apple fails to report prior year data on those issues, which reveal negative trends, the report does provide such data on other topics—those where this year’s data is better than that of prior years.

The effects of Apple’s reforms are often dubious and overstated by the company. For example, in reporting that 92 percent of the time workers in its supply chain are working less than 60 hours per week, Apple ignores the fact that workweeks at its Chinese factories still consistently break Chinese law, which restricts workweeks to less than 50 hours and which Apple has repeatedly pledged to uphold. The average workweek Apple reports still exceeds this legal limit by a substantial margin. Apple also continues to make the remarkable claim that nearly all its suppliers have achieved freedom of association (the right to organize unions and bargain collectively), saying its suppliers achieved 96 percent compliance with this standard. As Apple is aware, such freedom is non-existent in China. Independent unions are illegal. Workers who try to form them go to jail. Moreover, the information available about a program run by the Fair Labor Association (FLA), which was supposedly going to provide a greater voice for Apple’s workers (within the cramped confines of Chinese law), indicates it has fallen woefully short of its stated goals. Further, Apple touts training programs under which, according to the company, 2.3 million workers were trained in labor rights in 2014. This is a large number, to be sure; unfortunately, it is the suppliers themselves, not worker rights advocates or worker representatives (and not even Apple or its new training academy), that provide this training—and Apple provides no substantive information on its actual content or impact. Independent reports indicate that this management-provided training may be entirely cursory. (Apple’s repudiation of the use of bonded foreign labor was a positive step, but does not address the much larger, multi-faceted problem within Apple’s supply chain in China of the excessive use of domestic labor hired through dispatch agencies.)

Less Than Half the Truth: Jobs and Wages in Export Industries

Trade is a hot topic on Capitol Hill this year. President Obama has asked members of Congress for “fast track” trade promotion authority in order to finalize proposed trade deals with Asia and Europe that set the stage for growing, trade-related job displacement. One of the president’s core, frequently repeated arguments for these trade and investment deals is that “our businesses export more than ever, and exporters tend to pay their workers higher wages.” But that’s less than half the story. Trade is a two-way street, and talking about exports without considering imports is like keeping score in a baseball game by counting only the runs scored by the home team. It might make you feel good, but it won’t tell you who’s winning the game. Sadly, when it comes to trade and wages, trade is driving down the average wages of American workers because the United States runs large trade deficits with the world as a whole, including many countries in Asia and Europe—the regions targeted in current trade negotiations.

A case in point is provided by U.S. trade with China, which was responsible for nearly half (46.5 percent) of our $736.8 billion goods trade deficit in 2014. Jobs in industries exporting to China did pay well in 2009-2011 (the last years for which we have complete wage data)—an average of $872.89 per week, or 10.3 percent more than workers making non-traded goods and services (who earned only $791.14 per week), as shown in the figure below. However, workers in import-competing industries were paid even better—an average of $1,021.66 per week, or 29.1 percent more than workers in non-traded industries.

Congress and President Obama Cannot Sit Idly By While Companies Use H-1B Guestworkers to Replace American Workers

A recent investigation by Computerworld revealed that hundreds of information technology (IT) workers were laid off by Southern California Edison (SCE) and replaced with temporary foreign workers through the H-1B guestworker visa program, which allows employers to hire temporary foreign workers for up to six years if they have at least a college degree (most work in IT). The replacement H-1B workers are employed by two India-based IT services firms that specialize in outsourcing and offshoring U.S. jobs: Infosys and Tata Consultancy Services. While U.S. Sen. Jeff Sessions (R-Ala.) and Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Calif.) have publicly criticized the move, it doesn’t look like any action will be taken to reverse it.

SCE describes itself as “one of the nation’s largest electric utilities…deliver[ing] power to more than 14 million people.” SCE earned net profits of $1.4 billion on $13.2 billion in revenues over the past year. The company’s stock price is up 10 percent over that time and it pays its investors a 4.8 percent yield in dividends. An observer could be forgiven for believing that a job delivering safe and reliable power to homes in the United States might be reasonably safe from being offshored to India or even outsourced to temporary foreign workers. But he or she would be mistaken. In fact, the SCE case is just one more example in a long line of cases in which American workers are being replaced by H-1B workers.

Adding to the injustice, American workers losing their jobs are being forced to do “knowledge transfers,” an ugly euphemism that means being forced to train your own foreign replacement.

Americans should be outraged that most of our politicians sit idly by while outsourcing firms hijack the nation’s temporary foreign worker programs. Unpublished H-1B data from United States Citizenship and Immigration Services reveals the scale of the problem: A majority of H-1B visas are now being used by firms that displace American workers and facilitate the offshoring of high-wage jobs.

The Unemployed Exceed Job Openings in Almost Every Industry

One of the recurring myths following the Great Recession has been that recovery in the labor market has lagged because workers don’t have the right skills. The figure below, which shows the number of unemployed workers and the number of job openings in December by industry, is a useful way to examine this idea. If today’s labor market woes were the result of skills shortages or mismatches, we would expect to see some sectors where there are more unemployed workers than job openings, and others where there are more job openings than unemployed workers. What we find, however, is that there are more unemployed workers than jobs openings in almost every industry.

The notable exception is health care and social assistance, which has been consistently adding jobs throughout the business cycle. There is now one unemployed worker for every job opening in that sector, suggesting a tighter labor market for those workers. However, we have yet to see any sign of decent wage gains yet, which would be the final indicator that the labor market, at least for those workers, were approaching reasonable health.

Other sectors have seen little-to-no improvement in their job-seekers-to-job-openings ratios. There are still about six unemployed construction workers for every job opening. In other words, despite claims from some employers, there is no shortage of construction workers.

Taken as a whole, these numbers demonstrate that the main problem in the labor market is a broad-based lack of demand for workers—not available workers lacking the skills needed for the sectors with job openings.

Unemployed and job openings, by industry (in millions)

| Industry | Unemployed | Job openings |

|---|---|---|

| Professional and business services | 1.0833 | 0.8846 |

| Health care and social assistance | 0.7053 | 0.7228 |

| Retail trade | 1.0993 | 0.4843 |

| Accommodation and food services | 0.9564 | 0.5871 |

| Government | 0.6781 | 0.4474 |

| Finance and insurance | 0.2590 | 0.2308 |

| Durable goods manufacturing | 0.4543 | 0.1803 |

| Other services | 0.3686 | 0.1476 |

| Wholesale trade | 0.1610 | 0.1525 |

| Transportation, warehousing, and utilities | 0.3565 | 0.1648 |

| Information | 0.1535 | 0.0992 |

| Construction | 0.7621 | 0.1273 |

| Nondurable goods manufacturing | 0.3002 | 0.1084 |

| Educational services | 0.2298 | 0.0793 |

| Real estate and rental and leasing | 0.1139 | 0.0569 |

| Arts, entertainment, and recreation | 0.2117 | 0.0698 |

| Mining and logging | 0.0524 | 0.0293 |

Note: Because the data are not seasonally adjusted, these are 12-month averages, January 2014–December 2014.

Source: EPI analysis of data from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey and the Current Population Survey

Layoffs and Quits Hold Steady in December

The hires, quits, and layoffs rates all held fairly steady in the December Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS). As you can see in the figure below, layoffs shot up during the recession but recovered quickly and have been at prerecession levels for more than three years. The fact that this trend continued in December is a good sign. That said, not only do layoffs need to come down before we see a full recovery in the labor market, but hiring needs to pick up. While the hires rate has been generally improving, it’s still below its prerecession level.

The voluntary quits rate had been flat since February (1.8 percent), and saw a modest spike up in September to 2.0 percent, before falling to 1.9 percent in October and holding steady through December. A larger number of people voluntarily quitting their jobs indicates a strong labor market—one where workers are able to leave jobs that are not right for them and find new ones. In December, the quits rate was still 9.2 percent lower than it was in 2007, before the recession began.

Over the year, the quits rate has averaged 1.8 percent, an improvement over its average rate of 1.4 percent in 2009 and 2010. Each consecutive year has seen modest improvement, an average increase in the quits rate of 0.1 percentage points per year. Before long, we should look for a return to pre-recession levels of voluntary quits, which would mean that fewer workers are locked into jobs they would leave if they could.

Hires, quits, and layoff rates, December 2000–December 2014

| Month | Hires rate | Layoffs rate | Quits rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dec-2000 | 4.1% | 1.4% | 2.3% |

| Jan-2001 | 4.4% | 1.6% | 2.6% |

| Feb-2001 | 4.1% | 1.4% | 2.5% |

| Mar-2001 | 4.2% | 1.6% | 2.4% |

| Apr-2001 | 4.0% | 1.5% | 2.4% |

| May-2001 | 4.0% | 1.5% | 2.4% |

| Jun-2001 | 3.8% | 1.5% | 2.3% |

| Jul-2001 | 3.9% | 1.5% | 2.2% |

| Aug-2001 | 3.8% | 1.4% | 2.1% |

| Sep-2001 | 3.8% | 1.6% | 2.1% |

| Oct-2001 | 3.8% | 1.7% | 2.2% |

| Nov-2001 | 3.7% | 1.6% | 2.0% |

| Dec-2001 | 3.7% | 1.4% | 2.0% |

| Jan-2002 | 3.7% | 1.4% | 2.2% |

| Feb-2002 | 3.7% | 1.5% | 2.0% |

| Mar-2002 | 3.5% | 1.4% | 1.9% |

| Apr-2002 | 3.8% | 1.5% | 2.1% |

| May-2002 | 3.8% | 1.5% | 2.1% |

| Jun-2002 | 3.7% | 1.4% | 2.0% |

| Jul-2002 | 3.8% | 1.5% | 2.1% |

| Aug-2002 | 3.7% | 1.4% | 2.0% |

| Sep-2002 | 3.7% | 1.4% | 2.0% |

| Oct-2002 | 3.7% | 1.4% | 2.0% |

| Nov-2002 | 3.8% | 1.5% | 1.9% |

| Dec-2002 | 3.8% | 1.5% | 2.0% |

| Jan-2003 | 3.8% | 1.5% | 1.9% |

| Feb-2003 | 3.6% | 1.5% | 1.9% |

| Mar-2003 | 3.4% | 1.4% | 1.9% |

| Apr-2003 | 3.6% | 1.6% | 1.8% |

| May-2003 | 3.5% | 1.5% | 1.8% |

| Jun-2003 | 3.7% | 1.6% | 1.8% |

| Jul-2003 | 3.6% | 1.6% | 1.8% |

| Aug-2003 | 3.6% | 1.5% | 1.8% |

| Sep-2003 | 3.7% | 1.5% | 1.9% |

| Oct-2003 | 3.8% | 1.4% | 1.9% |

| Nov-2003 | 3.6% | 1.4% | 1.9% |

| Dec-2003 | 3.8% | 1.5% | 1.9% |

| Jan-2004 | 3.7% | 1.5% | 1.9% |

| Feb-2004 | 3.6% | 1.4% | 1.9% |

| Mar-2004 | 3.9% | 1.4% | 2.0% |

| Apr-2004 | 3.9% | 1.5% | 2.0% |

| May-2004 | 3.8% | 1.4% | 1.9% |

| Jun-2004 | 3.8% | 1.4% | 2.0% |

| Jul-2004 | 3.7% | 1.4% | 2.0% |

| Aug-2004 | 3.9% | 1.5% | 2.0% |

| Sep-2004 | 3.8% | 1.4% | 2.0% |

| Oct-2004 | 3.9% | 1.4% | 2.0% |

| Nov-2004 | 3.9% | 1.5% | 2.1% |

| Dec-2004 | 4.0% | 1.5% | 2.1% |

| Jan-2005 | 3.9% | 1.4% | 2.1% |

| Feb-2005 | 3.9% | 1.4% | 2.0% |

| Mar-2005 | 3.9% | 1.5% | 2.1% |

| Apr-2005 | 4.0% | 1.4% | 2.1% |

| May-2005 | 3.9% | 1.4% | 2.1% |

| Jun-2005 | 3.9% | 1.5% | 2.1% |

| Jul-2005 | 3.9% | 1.4% | 2.0% |

| Aug-2005 | 4.0% | 1.4% | 2.2% |

| Sep-2005 | 4.0% | 1.4% | 2.3% |

| Oct-2005 | 3.8% | 1.3% | 2.2% |

| Nov-2005 | 3.9% | 1.2% | 2.2% |

| Dec-2005 | 3.7% | 1.3% | 2.1% |

| Jan-2006 | 3.9% | 1.3% | 2.1% |

| Feb-2006 | 3.9% | 1.3% | 2.2% |

| Mar-2006 | 3.9% | 1.2% | 2.2% |

| Apr-2006 | 3.8% | 1.3% | 2.1% |

| May-2006 | 4.0% | 1.4% | 2.2% |

| Jun-2006 | 3.9% | 1.2% | 2.2% |

| Jul-2006 | 3.9% | 1.3% | 2.2% |

| Aug-2006 | 3.8% | 1.2% | 2.2% |

| Sep-2006 | 3.8% | 1.3% | 2.1% |

| Oct-2006 | 3.8% | 1.3% | 2.1% |

| Nov-2006 | 4.0% | 1.3% | 2.3% |

| Dec-2006 | 3.8% | 1.3% | 2.2% |

| Jan-2007 | 3.8% | 1.2% | 2.2% |

| Feb-2007 | 3.8% | 1.3% | 2.2% |

| Mar-2007 | 3.8% | 1.3% | 2.2% |

| Apr-2007 | 3.7% | 1.3% | 2.1% |

| May-2007 | 3.8% | 1.3% | 2.2% |

| Jun-2007 | 3.8% | 1.3% | 2.0% |

| Jul-2007 | 3.7% | 1.3% | 2.1% |

| Aug-2007 | 3.7% | 1.3% | 2.1% |

| Sep-2007 | 3.7% | 1.5% | 1.9% |

| Oct-2007 | 3.8% | 1.4% | 2.1% |

| Nov-2007 | 3.7% | 1.4% | 2.0% |

| Dec-2007 | 3.6% | 1.3% | 2.0% |

| Jan-2008 | 3.5% | 1.3% | 2.0% |

| Feb-2008 | 3.5% | 1.4% | 2.0% |

| Mar-2008 | 3.4% | 1.3% | 1.9% |

| Apr-2008 | 3.5% | 1.3% | 2.1% |

| May-2008 | 3.3% | 1.3% | 1.9% |

| Jun-2008 | 3.5% | 1.5% | 1.9% |

| Jul-2008 | 3.3% | 1.4% | 1.8% |

| Aug-2008 | 3.3% | 1.6% | 1.7% |

| Sep-2008 | 3.1% | 1.4% | 1.8% |

| Oct-2008 | 3.3% | 1.6% | 1.8% |

| Nov-2008 | 2.9% | 1.6% | 1.5% |

| Dec-2008 | 3.2% | 1.8% | 1.6% |

| Jan-2009 | 3.1% | 1.9% | 1.5% |

| Feb-2009 | 3.0% | 1.9% | 1.5% |

| Mar-2009 | 2.8% | 1.8% | 1.4% |

| Apr-2009 | 2.9% | 2.0% | 1.3% |

| May-2009 | 2.8% | 1.6% | 1.3% |

| Jun-2009 | 2.8% | 1.6% | 1.3% |

| Jul-2009 | 2.9% | 1.7% | 1.3% |

| Aug-2009 | 2.9% | 1.6% | 1.3% |

| Sep-2009 | 3.0% | 1.6% | 1.3% |

| Oct-2009 | 2.9% | 1.5% | 1.3% |

| Nov-2009 | 3.1% | 1.4% | 1.4% |

| Dec-2009 | 2.9% | 1.5% | 1.3% |

| Jan-2010 | 3.0% | 1.4% | 1.3% |

| Feb-2010 | 2.9% | 1.4% | 1.3% |

| Mar-2010 | 3.2% | 1.4% | 1.4% |

| Apr-2010 | 3.1% | 1.3% | 1.5% |

| May-2010 | 3.4% | 1.3% | 1.4% |

| Jun-2010 | 3.1% | 1.5% | 1.5% |

| Jul-2010 | 3.2% | 1.6% | 1.4% |

| Aug-2010 | 3.0% | 1.4% | 1.4% |

| Sep-2010 | 3.1% | 1.4% | 1.4% |

| Oct-2010 | 3.1% | 1.3% | 1.4% |

| Nov-2010 | 3.2% | 1.4% | 1.4% |

| Dec-2010 | 3.2% | 1.4% | 1.5% |

| Jan-2011 | 3.0% | 1.3% | 1.4% |

| Feb-2011 | 3.1% | 1.3% | 1.4% |

| Mar-2011 | 3.2% | 1.3% | 1.5% |

| Apr-2011 | 3.2% | 1.3% | 1.5% |

| May-2011 | 3.1% | 1.3% | 1.5% |

| Jun-2011 | 3.3% | 1.4% | 1.5% |

| Jul-2011 | 3.1% | 1.3% | 1.5% |

| Aug-2011 | 3.2% | 1.3% | 1.5% |

| Sep-2011 | 3.3% | 1.3% | 1.5% |

| Oct-2011 | 3.2% | 1.3% | 1.5% |

| Nov-2011 | 3.2% | 1.3% | 1.5% |

| Dec-2011 | 3.2% | 1.3% | 1.5% |

| Jan-2012 | 3.2% | 1.2% | 1.5% |

| Feb-2012 | 3.3% | 1.3% | 1.6% |

| Mar-2012 | 3.3% | 1.2% | 1.6% |

| Apr-2012 | 3.2% | 1.4% | 1.6% |

| May-2012 | 3.3% | 1.4% | 1.6% |

| Jun-2012 | 3.2% | 1.3% | 1.6% |

| Jul-2012 | 3.2% | 1.2% | 1.6% |

| Aug-2012 | 3.3% | 1.4% | 1.6% |

| Sep-2012 | 3.1% | 1.3% | 1.4% |

| Oct-2012 | 3.2% | 1.3% | 1.5% |

| Nov-2012 | 3.3% | 1.3% | 1.6% |

| Dec-2012 | 3.2% | 1.2% | 1.6% |

| Jan-2013 | 3.2% | 1.2% | 1.7% |

| Feb-2013 | 3.4% | 1.2% | 1.7% |

| Mar-2013 | 3.2% | 1.3% | 1.6% |

| Apr-2013 | 3.3% | 1.3% | 1.6% |

| May-2013 | 3.3% | 1.3% | 1.6% |

| Jun-2013 | 3.2% | 1.2% | 1.6% |

| Jul-2013 | 3.3% | 1.2% | 1.7% |

| Aug-2013 | 3.4% | 1.2% | 1.7% |

| Sep-2013 | 3.4% | 1.3% | 1.7% |

| Oct-2013 | 3.3% | 1.1% | 1.8% |

| Nov-2013 | 3.3% | 1.1% | 1.8% |

| Dec-2013 | 3.3% | 1.2% | 1.8% |

| Jan-2014 | 3.3% | 1.2% | 1.7% |

| Feb-2014 | 3.4% | 1.2% | 1.8% |

| Mar-2014 | 3.4% | 1.2% | 1.8% |

| Apr-2014 | 3.5% | 1.2% | 1.8% |

| May-2014 | 3.4% | 1.2% | 1.8% |

| Jun-2014 | 3.5% | 1.2% | 1.8% |

| Jul-2014 | 3.6% | 1.2% | 1.8% |

| Aug-2014 | 3.4% | 1.2% | 1.8% |

| Sep-2014 | 3.6% | 1.2% | 2.0% |

| Oct-2014 | 3.7% | 1.3% | 1.9% |

| Nov-2014 | 3.6% | 1.2% | 1.9% |

| Dec-2014 | 3.7% | 1.2% | 1.9% |

Note: Shaded areas denote recessions. The hires rate is the number of hires during the entire month as a percent of total employment. The layoff rate is the number of layoffs and discharges during the entire month as a percent of total employment. The quits rate is the number of quits during the entire month as a percent of total employment.

Source: EPI analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey

Job Openings Were Stronger in 2014 than 2013 or 2012, but We Have Still Not Fully Recovered

The number of job openings hit 5.0 million in December, according to this morning’s Job Openings and Labor Turnover Summary (JOLTS)—a slight increase from 4.8 million in November. Meanwhile, according to the Census’s Current Population Survey, there was a slight drop in people looking for work, to 8.7 million. Taken together, this means there were 1.7 times as many job seekers as job openings in December—the lowest this ratio has been since November 2007.

This slight decline in the jobs-seekers-to-job-openings ratio is a continuation of its steady decrease, since its high of 6.8-to-1 in July 2009, as you can see in the figure below. If the economy were stronger, the ratio would be even smaller—a 1-to-1 ratio would mean that there were roughly as many job openings as job seekers—but this indicates that we are moving in the right direction.

With the December data, we can also look at what’s happened throughout 2014, compared to the rest of the recovery. The job-seekers-to-jobs-openings ratio has been consistently falling, from a high of 5.9 percent in 2009 down to an average of 2.1 percent average in 2014. The average annual ratio fell 0.8 over the last year.

While the outlook for jobless workers is clearly improving, the job-seekers-to-jobs-openings ratio fails to account for the full extent of declines in labor force participation over the course of the recovery. 8.7 million unemployed workers understates how many job openings will be needed when a robust jobs recovery finally begins, due to the 6.1 million potential workers (in December) who are currently not in the labor market, but who would be if job opportunities were strong. Many of these “missing workers” will go back to looking for a job when the labor market picks up, so job openings will be needed for them, too.

The job-seekers ratio, December 2000–December 2014

| Month | Unemployed job seekers per job opening |

|---|---|

| Dec-2000 | 1.1 |

| Jan-2001 | 1.1 |

| Feb-2001 | 1.3 |

| Mar-2001 | 1.3 |

| Apr-2001 | 1.3 |

| May-2001 | 1.4 |

| Jun-2001 | 1.5 |

| Jul-2001 | 1.5 |

| Aug-2001 | 1.7 |

| Sep-2001 | 1.8 |

| Oct-2001 | 2.1 |

| Nov-2001 | 2.3 |

| Dec-2001 | 2.3 |

| Jan-2002 | 2.3 |

| Feb-2002 | 2.4 |

| Mar-2002 | 2.3 |

| Apr-2002 | 2.6 |

| May-2002 | 2.4 |

| Jun-2002 | 2.5 |

| Jul-2002 | 2.5 |

| Aug-2002 | 2.4 |

| Sep-2002 | 2.5 |

| Oct-2002 | 2.4 |

| Nov-2002 | 2.4 |

| Dec-2002 | 2.8 |

| Jan-2003 | 2.3 |

| Feb-2003 | 2.5 |

| Mar-2003 | 2.8 |

| Apr-2003 | 2.8 |

| May-2003 | 2.8 |

| Jun-2003 | 2.8 |

| Jul-2003 | 2.8 |

| Aug-2003 | 2.7 |

| Sep-2003 | 2.9 |

| Oct-2003 | 2.7 |

| Nov-2003 | 2.6 |

| Dec-2003 | 2.5 |

| Jan-2004 | 2.5 |

| Feb-2004 | 2.4 |

| Mar-2004 | 2.5 |

| Apr-2004 | 2.4 |

| May-2004 | 2.2 |

| Jun-2004 | 2.4 |

| Jul-2004 | 2.1 |

| Aug-2004 | 2.2 |

| Sep-2004 | 2.1 |

| Oct-2004 | 2.1 |

| Nov-2004 | 2.3 |

| Dec-2004 | 2.1 |

| Jan-2005 | 2.2 |

| Feb-2005 | 2.1 |

| Mar-2005 | 2.0 |

| Apr-2005 | 1.9 |

| May-2005 | 2.0 |

| Jun-2005 | 1.9 |

| Jul-2005 | 1.8 |

| Aug-2005 | 1.8 |

| Sep-2005 | 1.8 |

| Oct-2005 | 1.8 |

| Nov-2005 | 1.7 |

| Dec-2005 | 1.7 |

| Jan-2006 | 1.7 |

| Feb-2006 | 1.7 |

| Mar-2006 | 1.6 |

| Apr-2006 | 1.6 |

| May-2006 | 1.6 |

| Jun-2006 | 1.6 |

| Jul-2006 | 1.8 |

| Aug-2006 | 1.6 |

| Sep-2006 | 1.5 |

| Oct-2006 | 1.5 |

| Nov-2006 | 1.5 |

| Dec-2006 | 1.5 |

| Jan-2007 | 1.6 |

| Feb-2007 | 1.5 |

| Mar-2007 | 1.4 |

| Apr-2007 | 1.5 |

| May-2007 | 1.5 |

| Jun-2007 | 1.5 |

| Jul-2007 | 1.6 |

| Aug-2007 | 1.6 |

| Sep-2007 | 1.6 |

| Oct-2007 | 1.7 |

| Nov-2007 | 1.7 |

| Dec-2007 | 1.8 |

| Jan-2008 | 1.8 |

| Feb-2008 | 1.9 |

| Mar-2008 | 1.9 |

| Apr-2008 | 2.0 |

| May-2008 | 2.1 |

| Jun-2008 | 2.3 |

| Jul-2008 | 2.4 |

| Aug-2008 | 2.6 |

| Sep-2008 | 3.0 |

| Oct-2008 | 3.1 |

| Nov-2008 | 3.4 |

| Dec-2008 | 3.7 |

| Jan-2009 | 4.4 |

| Feb-2009 | 4.6 |

| Mar-2009 | 5.4 |

| Apr-2009 | 6.1 |

| May-2009 | 6.0 |

| Jun-2009 | 6.2 |

| Jul-2009 | 6.8 |

| Aug-2009 | 6.5 |

| Sep-2009 | 6.2 |

| Oct-2009 | 6.5 |

| Nov-2009 | 6.3 |

| Dec-2009 | 6.1 |

| Jan-2010 | 5.5 |

| Feb-2010 | 6.0 |

| Mar-2010 | 5.8 |

| Apr-2010 | 5.0 |

| May-2010 | 5.1 |

| Jun-2010 | 5.3 |

| Jul-2010 | 5.0 |

| Aug-2010 | 5.0 |

| Sep-2010 | 5.2 |

| Oct-2010 | 4.8 |

| Nov-2010 | 4.9 |

| Dec-2010 | 5.0 |

| Jan-2011 | 4.8 |

| Feb-2011 | 4.6 |

| Mar-2011 | 4.4 |

| Apr-2011 | 4.5 |

| May-2011 | 4.5 |

| Jun-2011 | 4.3 |

| Jul-2011 | 4.0 |

| Aug-2011 | 4.3 |

| Sep-2011 | 3.9 |

| Oct-2011 | 4.0 |

| Nov-2011 | 4.2 |

| Dec-2011 | 3.7 |

| Jan-2012 | 3.5 |

| Feb-2012 | 3.7 |

| Mar-2012 | 3.3 |

| Apr-2012 | 3.5 |

| May-2012 | 3.4 |

| Jun-2012 | 3.3 |

| Jul-2012 | 3.5 |

| Aug-2012 | 3.4 |

| Sep-2012 | 3.4 |

| Oct-2012 | 3.2 |

| Nov-2012 | 3.2 |

| Dec-2012 | 3.4 |

| Jan-2013 | 3.3 |

| Feb-2013 | 3.0 |

| Mar-2013 | 3.0 |

| Apr-2013 | 3.1 |

| May-2013 | 3.0 |

| Jun-2013 | 3.0 |

| Jul-2013 | 3.0 |

| Aug-2013 | 2.9 |

| Sep-2013 | 2.8 |

| Oct-2013 | 2.8 |

| Nov-2013 | 2.6 |

| Dec-2013 | 2.6 |

| Jan-2014 | 2.6 |

| Feb-2014 | 2.5 |

| Mar-2014 | 2.5 |

| Apr-2014 | 2.2 |

| May-2014 | 2.1 |

| Jun-2014 | 2.0 |

| Jul-2014 | 2.1 |

| Aug-2014 | 2.0 |

| Sep-2014 | 2.0 |

| Oct-2014 | 1.9 |

| Nov-2014 | 1.9 |

| Dec-2014 | 1.7 |

Note: Shaded areas denote recessions.

Source: EPI analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey and Current Population Survey

Increasing Labor Force Participation Leads to Fewer Missing Workers

The official unemployment rate ticked up slightly last month as more potential workers entered the labor force. While is it a positive sign that more people are actively looking for work, the unemployment rate still understates the weakness of job opportunities. This is due to the existence of a large pool of “missing workers”—potential workers who, because of weak job opportunities, are neither employed nor actively seeking a job. In other words, these are people who would be either working or looking for work if job opportunities were significantly stronger.

The number of missing workers has been hovering around 6 million for over a year. They fell slightly in January, which could be the start of a positive trend. As the economy gets stronger, I would expect more people to start looking for work. At this point, the fact remains that there are still 5.8 million missing workers. And, if the missing workers were actively looking for work, the unemployment rate would be 9.0 percent.

Millions of potential workers sidelined: Missing workers,* January 2006–January 2015

| Date | Missing workers |

|---|---|

| 2006-01-01 | 530,000 |

| 2006-02-01 | 110,000 |

| 2006-03-01 | 110,000 |

| 2006-04-01 | 250,000 |

| 2006-05-01 | 210,000 |

| 2006-06-01 | 110,000 |

| 2006-07-01 | 60,000 |

| 2006-08-01 | -120,000 |

| 2006-09-01 | 120,000 |

| 2006-10-01 | -50,000 |

| 2006-11-01 | -220,000 |

| 2006-12-01 | -500,000 |

| 2007-01-01 | -460,000 |

| 2007-02-01 | -210,000 |

| 2007-03-01 | -150,000 |

| 2007-04-01 | 650,000 |

| 2007-05-01 | 560,000 |

| 2007-06-01 | 360,000 |

| 2007-07-01 | 370,000 |

| 2007-08-01 | 840,000 |

| 2007-09-01 | 410,000 |

| 2007-10-01 | 800,000 |

| 2007-11-01 | 280,000 |

| 2007-12-01 | 250,000 |

| 2008-01-01 | -320,000 |

| 2008-02-01 | 220,000 |

| 2008-03-01 | 50,000 |

| 2008-04-01 | 340,000 |

| 2008-05-01 | -60,000 |

| 2008-06-01 | 20,000 |

| 2008-07-01 | -70,000 |

| 2008-08-01 | -90,000 |

| 2008-09-01 | 180,000 |

| 2008-10-01 | 60,000 |

| 2008-11-01 | 420,000 |

| 2008-12-01 | 420,000 |

| 2009-01-01 | 710,000 |

| 2009-02-01 | 620,000 |

| 2009-03-01 | 1,050,000 |

| 2009-04-01 | 750,000 |

| 2009-05-01 | 650,000 |

| 2009-06-01 | 650,000 |

| 2009-07-01 | 1,040,000 |

| 2009-08-01 | 1,320,000 |

| 2009-09-01 | 2,050,000 |

| 2009-10-01 | 2,270,000 |

| 2009-11-01 | 2,300,000 |

| 2009-12-01 | 3,120,000 |

| 2010-01-01 | 2,770,000 |

| 2010-02-01 | 2,690,000 |

| 2010-03-01 | 2,440,000 |

| 2010-04-01 | 1,940,000 |

| 2010-05-01 | 2,530,000 |

| 2010-06-01 | 2,950,000 |

| 2010-07-01 | 3,220,000 |

| 2010-08-01 | 2,830,000 |

| 2010-09-01 | 3,200,000 |

| 2010-10-01 | 3,640,000 |

| 2010-11-01 | 3,310,000 |

| 2010-12-01 | 3,800,000 |

| 2011-01-01 | 3,910,000 |

| 2011-02-01 | 4,110,000 |

| 2011-03-01 | 3,960,000 |

| 2011-04-01 | 4,000,000 |

| 2011-05-01 | 4,110,000 |

| 2011-06-01 | 4,220,000 |

| 2011-07-01 | 4,640,000 |

| 2011-08-01 | 4,100,000 |

| 2011-09-01 | 3,990,000 |

| 2011-10-01 | 4,090,000 |

| 2011-11-01 | 4,090,000 |

| 2011-12-01 | 4,150,000 |

| 2012-01-01 | 4,450,000 |

| 2012-02-01 | 4,180,000 |

| 2012-03-01 | 4,240,000 |

| 2012-04-01 | 4,630,000 |

| 2012-05-01 | 4,240,000 |

| 2012-06-01 | 4,060,000 |

| 2012-07-01 | 4,520,000 |

| 2012-08-01 | 4,630,000 |

| 2012-09-01 | 4,500,000 |

| 2012-10-01 | 3,930,000 |

| 2012-11-01 | 4,370,000 |

| 2012-12-01 | 4,070,000 |

| 2013-01-01 | 4,350,000 |

| 2013-02-01 | 4,790,000 |

| 2013-03-01 | 5,310,000 |

| 2013-04-01 | 5,060,000 |

| 2013-05-01 | 4,840,000 |

| 2013-06-01 | 4,700,000 |

| 2013-07-01 | 5,030,000 |

| 2013-08-01 | 5,150,000 |

| 2013-09-01 | 5,370,000 |

| 2013-10-01 | 6,120,000 |

| 2013-11-01 | 5,700,000 |

| 2013-12-01 | 5,950,000 |

| 2014-01-01 | 5,850,000 |

| 2014-02-01 | 5,650,000 |

| 2014-03-01 | 5,330,000 |

| 2014-04-01 | 6,210,000 |

| 2014-05-01 | 5,940,000 |

| 2014-06-01 | 5,950,000 |

| 2014-07-01 | 5,810,000 |

| 2014-08-01 | 5,890,000 |

| 2014-09-01 | 6,250,000 |

| 2014-10-01 | 5,720,000 |

| 2014-11-01 | 5,760,000 |

| 2014-12-01 | 6,100,000 |

| 2015-01-01 | 5,760,000 |

* Potential workers who, due to weak job opportunities, are neither employed nor actively seeking work

Note: Volatility in the number of missing workers in 2006–2008, including cases of negative numbers of missing workers, is simply the result of month-to-month variability in the sample. The Great Recession–induced pool of missing workers began to form and grow starting in late 2008.

Source: EPI analysis of Mitra Toossi, “Labor Force Projections to 2016: More Workers in Their Golden Years,” Bureau of Labor Statistics Monthly Labor Review, November 2007; and Current Population Survey public data series

Similarly, we saw a tick up in the employment-to-population ratio for prime-working-age population in January, following a trend that has been slowly moving in the right direction for years. That said, it’s clear that there is a long way to go before we return to pre-recession labor market health.

Employment-to-population ratio of workers ages 25–54, 2006–2015

| Month | Employment to population ratio |

|---|---|

| 2006-01-01 | 79.6% |

| 2006-02-01 | 79.7% |

| 2006-03-01 | 79.8% |

| 2006-04-01 | 79.6% |

| 2006-05-01 | 79.7% |

| 2006-06-01 | 79.8% |

| 2006-07-01 | 79.8% |

| 2006-08-01 | 79.8% |

| 2006-09-01 | 79.9% |

| 2006-10-01 | 80.1% |

| 2006-11-01 | 80.0% |

| 2006-12-01 | 80.1% |

| 2007-01-01 | 80.3% |

| 2007-02-01 | 80.1% |

| 2007-03-01 | 80.2% |

| 2007-04-01 | 80.0% |

| 2007-05-01 | 80.0% |

| 2007-06-01 | 79.9% |

| 2007-07-01 | 79.8% |

| 2007-08-01 | 79.8% |

| 2007-09-01 | 79.7% |

| 2007-10-01 | 79.6% |

| 2007-11-01 | 79.7% |

| 2007-12-01 | 79.7% |

| 2008-01-01 | 80.0% |

| 2008-02-01 | 79.9% |

| 2008-03-01 | 79.8% |

| 2008-04-01 | 79.6% |

| 2008-05-01 | 79.5% |

| 2008-06-01 | 79.4% |

| 2008-07-01 | 79.2% |

| 2008-08-01 | 78.8% |

| 2008-09-01 | 78.8% |

| 2008-10-01 | 78.4% |

| 2008-11-01 | 78.1% |

| 2008-12-01 | 77.6% |

| 2009-01-01 | 77.0% |

| 2009-02-01 | 76.7% |

| 2009-03-01 | 76.2% |

| 2009-04-01 | 76.2% |

| 2009-05-01 | 75.9% |

| 2009-06-01 | 75.9% |

| 2009-07-01 | 75.8% |

| 2009-08-01 | 75.6% |

| 2009-09-01 | 75.1% |

| 2009-10-01 | 75.0% |

| 2009-11-01 | 75.2% |

| 2009-12-01 | 74.8% |

| 2010-01-01 | 75.1% |

| 2010-02-01 | 75.1% |

| 2010-03-01 | 75.1% |

| 2010-04-01 | 75.4% |

| 2010-05-01 | 75.1% |

| 2010-06-01 | 75.2% |

| 2010-07-01 | 75.1% |

| 2010-08-01 | 75.0% |

| 2010-09-01 | 75.1% |

| 2010-10-01 | 75.0% |

| 2010-11-01 | 74.8% |

| 2010-12-01 | 75.0% |

| 2011-01-01 | 75.2% |

| 2011-02-01 | 75.1% |

| 2011-03-01 | 75.3% |

| 2011-04-01 | 75.1% |

| 2011-05-01 | 75.2% |

| 2011-06-01 | 75.0% |

| 2011-07-01 | 75.0% |

| 2011-08-01 | 75.1% |

| 2011-09-01 | 74.9% |

| 2011-10-01 | 74.9% |

| 2011-11-01 | 75.3% |

| 2011-12-01 | 75.4% |

| 2012-01-01 | 75.6% |

| 2012-02-01 | 75.6% |

| 2012-03-01 | 75.7% |

| 2012-04-01 | 75.7% |

| 2012-05-01 | 75.7% |

| 2012-06-01 | 75.7% |

| 2012-07-01 | 75.6% |

| 2012-08-01 | 75.7% |

| 2012-09-01 | 75.9% |

| 2012-10-01 | 76.0% |

| 2012-11-01 | 75.8% |

| 2012-12-01 | 75.9% |

| 2013-01-01 | 75.7% |

| 2013-02-01 | 75.9% |

| 2013-03-01 | 75.9% |

| 2013-04-01 | 75.9% |

| 2013-05-01 | 76.0% |

| 2013-06-01 | 75.9% |

| 2013-07-01 | 76.0% |

| 2013-08-01 | 75.9% |

| 2013-09-01 | 75.9% |

| 2013-10-01 | 75.5% |

| 2013-11-01 | 76.0% |

| 2013-12-01 | 76.1% |

| 2014-01-01 | 76.5% |

| 2014-02-01 | 76.5% |

| 2014-03-01 | 76.6% |

| 2014-04-01 | 76.5% |

| 2014-05-01 | 76.4% |

| 2014-06-01 | 76.8% |

| 2014-07-01 | 76.6% |

| 2014-08-01 | 76.8% |

| 2014-09-01 | 76.8% |

| 2014-10-01 | 76.9% |

| 2014-11-01 | 76.9% |

| 2014-12-01 | 77.0% |

| 2015-01-01 | 77.2% |

Source: EPI analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics' Current Population Survey public data series.

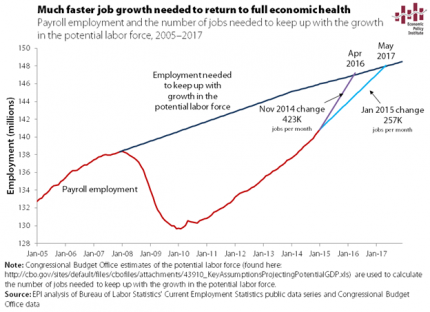

Much Stronger Job Growth is Needed If We’re Going to See a Healthy Economy Any Time Soon

Today’s job report is a solid start to the new year, and could be a sign that the economy has shifted into a slightly higher gear. At 257,000 jobs a month, we would get to pre-recession labor market health by May 2017 (as shown in the figure below).

The BLS revisions to 2014 payroll employment suggest moderately faster growth than initially reported last year, particularly in the last quarter of 2014. If we were to use the highest rate of growth last year—November’s 423,000 jobs added—in each ensuing month, we would return to 2007 labor market health by April 2016, over a year sooner.

There is no reason to expect a much faster growth rate of jobs, but stronger numbers on jobs will hopefully translate into decent wage growth sometime in the foreseeable future. It’s not there yet, but we can only hope.

Nominal Wage Growth Still Far Below Target

This morning’s jobs report showed the economy added 257,000 jobs in January, and the numbers for December and November were revised upward. But even with the positive revisions to 2014 and the solid jobs growth last month, there’s clearly still tremendous slack in the labor market, as evidenced by lagging nominal wage growth. While January’s 0.5 percent jump in wages is a good sign, it’s important not to read too much into any one month, as there’s considerable volatility in the series. Over the year, nominal average hourly earnings have only grown 2.2 percent. From the figure below, it is clear the nominal wage growth has been hovering around 2 percent for the last five years.

It is also apparent from the figure that nominal wages have grown far slower than any reasonable wage target. The fact is that the economy is not growing enough for workers to feel the effects in their paychecks and not enough for the Federal Reserve to slow the economy down out of fear of upcoming inflationary pressure. If the Fed acts too soon, it will slow labor share’s recovery and come at a cost to Americans’ living standards. It is imperative that the Fed keep their foot off the brake for as long as it takes to see modest (if not strong) wage growth for America’s workers.

Nominal wage growth has been far below target in the recovery: Year-over-year change in private-sector nominal average hourly earnings, 2007–2015

| All nonfarm employees | Production/nonsupervisory workers | |

|---|---|---|

| Mar-2007 | 3.6427146% | 4.1112455% |

| Apr-2007 | 3.3234127% | 3.8461538% |

| May-2007 | 3.7257824% | 4.1441441% |

| Jun-2007 | 3.8575668% | 4.1267943% |

| Jul-2007 | 3.4482759% | 4.0524434% |

| Aug-2007 | 3.5433071% | 4.0404040% |

| Sep-2007 | 3.2337090% | 4.1493776% |

| Oct-2007 | 3.2778865% | 3.7780401% |

| Nov-2007 | 3.3203125% | 3.8869258% |

| Dec-2007 | 3.1113272% | 3.8123167% |

| Jan-2008 | 3.1067961% | 3.8619075% |

| Feb-2008 | 3.0464217% | 3.7296037% |

| Mar-2008 | 3.0332210% | 3.7746806% |

| Apr-2008 | 2.8324532% | 3.7037037% |

| May-2008 | 3.0172414% | 3.6908881% |

| Jun-2008 | 2.6666667% | 3.6186100% |

| Jul-2008 | 3.0000000% | 3.7227950% |

| Aug-2008 | 3.2794677% | 3.8263849% |

| Sep-2008 | 3.2747983% | 3.6425726% |

| Oct-2008 | 3.3159640% | 3.9249147% |

| Nov-2008 | 3.5916824% | 3.8548753% |

| Dec-2008 | 3.6303630% | 3.8418079% |

| Jan-2009 | 3.5310734% | 3.7183099% |

| Feb-2009 | 3.4725481% | 3.6516854% |

| Mar-2009 | 3.1775701% | 3.5254617% |

| Apr-2009 | 3.2212885% | 3.2924107% |

| May-2009 | 2.8358903% | 3.0589544% |

| Jun-2009 | 2.7365492% | 2.9379157% |

| Jul-2009 | 2.5889968% | 2.7056875% |

| Aug-2009 | 2.4390244% | 2.6402640% |

| Sep-2009 | 2.2977941% | 2.7457441% |

| Oct-2009 | 2.3383769% | 2.6272578% |

| Nov-2009 | 2.0529197% | 2.6746725% |

| Dec-2009 | 1.8198362% | 2.5027203% |

| Jan-2010 | 1.9554343% | 2.6072787% |

| Feb-2010 | 1.8140590% | 2.4932249% |

| Mar-2010 | 1.7663043% | 2.2702703% |

| Apr-2010 | 1.7639077% | 2.4311183% |

| May-2010 | 1.8987342% | 2.5903940% |

| Jun-2010 | 1.7607223% | 2.4771136% |

| Jul-2010 | 1.8476791% | 2.4731183% |

| Aug-2010 | 1.7070979% | 2.4115756% |

| Sep-2010 | 1.8867925% | 2.2447889% |

| Oct-2010 | 1.8817204% | 2.5066667% |

| Nov-2010 | 1.6540009% | 2.1796917% |

| Dec-2010 | 1.7426273% | 2.0169851% |

| Jan-2011 | 1.9625335% | 2.2233986% |

| Feb-2011 | 1.8262806% | 2.1152829% |

| Mar-2011 | 1.8246551% | 2.1141649% |

| Apr-2011 | 1.9111111% | 2.1097046% |

| May-2011 | 2.0408163% | 2.1041557% |

| Jun-2011 | 2.1295475% | 2.0493957% |

| Jul-2011 | 2.2566372% | 2.2560336% |

| Aug-2011 | 1.9434629% | 1.9884877% |

| Sep-2011 | 1.9400353% | 1.9864088% |

| Oct-2011 | 2.1108179% | 1.7169615% |

| Nov-2011 | 2.0228672% | 1.8210198% |

| Dec-2011 | 1.9762846% | 1.8210198% |

| Jan-2012 | 1.7060367% | 1.3982393% |

| Feb-2012 | 1.9247594% | 1.5018125% |

| Mar-2012 | 2.1416084% | 1.7080745% |

| Apr-2012 | 2.0497165% | 1.7561983% |

| May-2012 | 1.7826087% | 1.4425554% |

| Jun-2012 | 1.9548219% | 1.5447992% |

| Jul-2012 | 1.7741238% | 1.3853258% |

| Aug-2012 | 1.8630849% | 1.3340174% |

| Sep-2012 | 1.9896194% | 1.3839057% |

| Oct-2012 | 1.4642550% | 1.2787724% |

| Nov-2012 | 1.8965517% | 1.4307614% |

| Dec-2012 | 2.1102498% | 1.6351559% |

| Jan-2013 | 2.1505376% | 1.8896834% |

| Feb-2013 | 2.1030043% | 2.0408163% |

| Mar-2013 | 1.8827557% | 1.8829517% |

| Apr-2013 | 1.9658120% | 1.7258883% |

| May-2013 | 2.0504058% | 1.8791265% |

| Jun-2013 | 2.1729868% | 2.0283976% |

| Jul-2013 | 1.9132653% | 1.9736842% |

| Aug-2013 | 2.2118248% | 2.1265823% |

| Sep-2013 | 2.0356234% | 2.1739130% |

| Oct-2013 | 2.2495756% | 2.2727273% |

| Nov-2013 | 2.1573604% | 2.2670025% |

| Dec-2013 | 1.9401097% | 2.3127200% |

| Jan-2014 | 1.9789474% | 2.2055138% |

| Feb-2014 | 2.1017234% | 2.4500000% |

| Mar-2014 | 2.1419572% | 2.2977023% |

| Apr-2014 | 1.9698240% | 2.2954092% |

| May-2014 | 2.0510674% | 2.3928215% |

| Jun-2014 | 1.9599666% | 2.2862823% |

| Jul-2014 | 2.0442219% | 2.2828784% |

| Aug-2014 | 2.1223471% | 2.4789291% |

| Sep-2014 | 1.9950125% | 2.2761009% |

| Oct-2014 | 1.9510170% | 2.2222222% |

| Nov-2014 | 1.9461698% | 2.1674877% |

| Dec-2014 | 1.6549441% | 1.6216216% |

| Jan-2015 | 2.1982742% | 1.9607843% |

* Nominal wage growth consistent with the Federal Reserve Board's 2 percent inflation target, 1.5 percent productivity growth, and a stable labor share of income.

Source: EPI analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Employment Statistics public data series

What to Watch on Jobs Day: Signs of a Tightening Labor Market?

The economy is slowly recovering from the Great Recession. We saw stronger job growth in 2014 than in 2013 or 2012. In 2015, I hope to see signs of even stronger job growth, pulling the missing workers back into the labor force, and achieving decent, if not strong, wage growth for most. I’ll be looking at these factors when the jobs report comes out tomorrow and throughout the year.

First, jobs growth. If we continue to see the average rate of job growth experienced in 2014, it will be the summer of 2017 when we return to pre-recession labor market health. 2014’s rate of job growth was a positive step, but I’m hoping for even more.

Second, labor force participation. While the unemployment rate continued to fall through 2014, it remains elevated across the population (by age, race, gender, education, sector, occupation)—and even so, it does not reflect the full picture of the labor market. Some of the decline is due to an increase in employment, but some of it is due to a drop in labor force participation. Between November and December 2014, 70 percent of the decline in the number of unemployed people was caused not by workers finding jobs but by people leaving the labor force, or not entering it in the first place.

To better explain this trend, we’ve been tracking what we call the “missing workers.” These are people who have left (or never entered) the labor force, but who would be working or looking for work if job opportunities were significantly more robust. Because jobless workers are only counted as unemployed if they are actively seeking work, these missing workers are not reflected in the official (U3) unemployment rate. We compare today’s labor force participation rate with projections based solely on structural changes in the workforce—like the retiring baby boomers—and find that there are currently 6.1 million missing workers. If these missing workers were actively looking for work, the unemployment rate would be 9.1 percent.

Obama’s Budget: Mostly a Political Document, and That’s Just Fine

This post originally ran on the Wall Street Journal‘s Think Tank blog.

The White House released its annual budget on Monday for fiscal year 2016. On the one hand, this may seem like a low-value exercise, given the dim prospects for its major initiatives passing a Republican-controlled Congress. But on the other hand, the raft of stories written about it prove the president continues to have unrivaled power in setting the terms of policy debate.

And the terms set by the 2016 budget are really useful.

Most of the big-ticket items were previewed: significant increases on tax rates for the highest-income households on income they receive simply from wealth-holdings, higher taxes on large transfers of wealth, tax cuts for low- and middle-income taxpayers, and substantial spending increases on community colleges, early childhood care, and infrastructure.

One item that wasn’t telegraphed by the White House included corporate tax reforms that would impose a minimum 19% tax on foreign earnings of U.S. firms with no opportunity for deferral. This is a very big step in the right direction, if still a little shy of perfect since deferral should be ended and U.S. firms should be taxed at the going corporate income tax rate regardless of where income is earned. But 19% is a lot better than today’s implicit 0% on income held abroad. Further, a large chunk of the budget’s infrastructure proposals is financed by a one-time tax of 14% on accumulated earnings of U.S. corporations held abroad. Again, this is much better than the frequently floated alternative of allowing U.S. firms to repatriate their foreign-held earnings at a preferential rate.

Ideas Good and Not so Good: Infrastructure Investment and Corporate Taxes

President Obama released his fiscal year 2016 budget proposal earlier this week. The proposal is full of good ideas, so-so ideas, and some not so good ideas. One great idea is to devote more money to the Highway Trust Fund for infrastructure investments, which improves job growth now and in the future. At the moment, however, it’s paired with the not-so good idea to pay for it with a mandatory one-time 14 percent tax on the $2 trillion of tax-deferred foreign earnings of U.S. corporations, which would bring in $268 billion over the six years. To be clear, this is an improvement over the other “one-time” corporate tax change often floated to realize a temporary revenue windfall—a full repatriation tax “holiday” for earnings accumulated overseas. So if the Obama proposal is a lot better than a full holiday, what’s the problem? The proposed one-time tax rate is still too low.

The 14 percent one-time tax is a transition tax to the president’s proposal to institute a 19 percent tax on corporate foreign-sourced earnings. Currently, corporate foreign-sourced earnings are subject to the U.S. corporate income tax, but payment of the tax is deferred (i.e., no U.S. taxes are paid at all) until the corporation brings to earnings to the United States (or in the jargon: repatriates the earnings). The earnings are then theoretically taxed at the statutory corporate tax rate of 35 percent, but due to various deductions and tax credits most corporations pay substantially less than the 35 percent rate. It is estimated that firms have stashed away $2 trillion in untaxed earnings overseas. One reason it makes sense for them to stash money overseas is that Congress has in the past offered a repatriation tax “holiday,” which allowed them to repatriate it at hugely preferential rates. And proposals to do this again have been percolating for years, so it makes a lot of sense for multinationals to wait and see if they get another windfall.

This largely explains why the business community, rather than jumping at the chance to face a 14 percent tax rate instead of the 35 percent rate, wants the transition tax rate to be no higher than 5 percent or even lower. Of course they can’t flat-out argue that they’re actually waiting for another pure windfall, so instead they argue the 14 percent rate somehow harms competitiveness, though they don’t explain how. Let’s examine this specious argument.

Firms compete over customers for their products and competitiveness, by its very nature, is forward looking since the past can’t be changed. The tax on income that has already been earned will not affect a firm’s behavior; the accumulated $2 trillion of untaxed income is based on past decisions, which cannot be changed. Consequently, there is no reason to tax this income at a rate less than the statutory corporate tax rate since there is no competitiveness issue. A lower tax rate just rewards firms for the aggressive tax planning that allowed them to accumulate $2 trillion in untaxed earnings.

TPP and Provisions to Stop Currency Management: Not That Hard

As discussions surrounding the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) heat up, there has been a new push to include provisions within the agreement to keep countries from managing the value of their currency for competitive gain vis-à-vis their trading partners. This push got an unexpected (by me, anyhow) boost recently when former U.S. Treasury Secretary and former Obama administration National Economic Council Director Larry Summers called for it (see page 22 in the link).

This currency management is a key cause of persistent U.S. trade deficits, and it is widespread. Given that our trade deficit drags on demand growth, and given that generating sufficient demand to reach full employment is likely to be a key economic problem in coming years, this is an important issue to address. Further, given that U.S. tariffs are extremely low, it’s hard to think of any other issue besides currency management that could possibly matter more for trade flows, so excluding it from the TPP seems odd. And yet many TPP proponents are extremely reluctant to include binding tools to stop currency management in the treaty. There have been many arguments for why the United States can’t or shouldn’t stop currency management, but the latest rationale is pretty novel: the claim is that including a currency chapter in the TPP would let other countries use the provisions of the treaty to stop the Federal Reserve from engaging in expansionary monetary policy. If such a provision had been in effect during the Great Recession, this argument continues, it would have kept the Fed from engaging in the quantitative easing (QE) that it undertook to blunt the recession and spur recovery.

Tying the Fed’s hands like this would indeed be a bad thing, but there’s no reason at all to think one couldn’t define currency management in way that did not constrain the Fed or any other central bank wanting to undertake similar maneuvers.

A Great Idea: End the Sequester

President Obama released his 2016 budget proposal this morning. While president’s budgets are rarely implemented, especially if Congress is controlled by the opposite party, they help to set the agenda for the upcoming legislative year. And this year the president has a great idea that should not be disregarded: ending the sequester.

The president has proposed increasing discretionary spending by over $70 billion, which would effectively put an end to the sequester-induced straight jacket on the budget. Half of the increase would be directed for defense discretionary spending and the other half for nondefense discretionary programs—i.e., the programs that fund public investments. While the proposed spending increase is not enough to meet our actual needs, it is a start.

As a reminder, the sequester is the result of legislation Congress passed and President Obama signed in 2011. At the time, the discretionary caps and sequester were a bad idea; today they are a bad and dangerous idea. This self-imposed austerity was the major factor in the slow recovery from the Great Recession. Recently, Erskine Bowles, a deficit hawk and co-chair of the 2010 National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform (often called Simpson-Bowles) said “I don’t think it gets any stupider than the sequester.” I agree. Let’s hope the president forcefully pushes Congress to end the stupid sequester.

Sluggish Wage Growth Continues Throughout 2014

Today, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released the Employment Cost Index (ECI), a closely watched measure of labor costs, for the last quarter of 2014. Nominal year-over-year compensation for private industry workers rose 2.3 percent, while private sector wages and salaries rose 2.2 percent.