New analyses of minimum wage increases in Minneapolis and Saint Paul are misleading, flawed, and should be ignored

This week, researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis released two analyses of the economic impact of several recent increases in the separate citywide minimum wages in Minneapolis and Saint Paul. The authors of the two separate, but linked, analyses interpret their findings as suggesting that the series of minimum wage increases reduced employment in the Twin Cities, but this conclusion is not supported even by the results presented in their own reports.

The data and methodology used in the study are simply not sufficient to distinguish between the effects of the minimum wage increases and other changes in employment happening around the same time. Even more problematic are the studies’ unsuccessful attempts to estimate effects through 2020, when the study’s methodology is unable to separate the effects of the minimum wage from the devastating impact of the pandemic on the two cities’ service-sector workforces. In fact, the studies’ findings implausibly suggest that the entire decline in restaurant employment during the pandemic is due to the minimum wage increases, as opposed to lockdowns, curfews, and pandemic-related declines in consumer spending on eating out.

Yes, the Build Back Better Act is fully paid for

EPI director of research Josh Bivens took to Twitter to refute critics’ most recent claim that the Build Back Better Act (BBBA) is only “fully paid for” due to accounting gimmicks. The claim, Bivens stresses, is “bad economics,” adding that BBBA is indeed fully paid for. Read the full Twitter thread explaining why below.

Children whose parents couldn’t find decent work? Underserving of a modest unconditional tax credit. Millionaire heirs? Deserving of maintenance of a zero tax rate on inherited capital gains. 2

— Josh Bivens (@joshbivens_DC) November 2, 2021

Latina Equal Pay Day: Latina workers remain greatly underpaid, including in front-line occupations

October 21 is Latina Equal Pay Day. Last year, a typical Latina worker who worked full-time, year-round earned only 57 cents for every dollar earned by white, non-Hispanic men. This means that Latinas on average must work nearly 22 months to earn what white, non-Hispanic men earn in 12 months.

The infographics below take a closer look at average hourly wages of Latinas and non-Hispanic white men employed in major occupations at the center of national efforts to address COVID-19, based on our previous analysis of Current Population Survey data from 2014-2019. These occupations include front-line workers in health care and essential businesses like grocery stores, those who have borne the brunt of job losses in the restaurant industry, and teachers and child care workers. We found that Latina workers make between 6% to 32% less than non-Hispanic white men in these occupations.

Few Midwestern states are providing premium pay to essential workers, despite American Rescue Plan funding

Key takeaways

- The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) allocated $195 billion in fiscal recovery funds directly to states.

- One of the key uses of the funds was for premium pay for front-line workers impacted by the pandemic, which would disproportionately benefit Black and Brown workers and women.

- However, only two Midwestern states—Michigan and Minnesota—are using American Rescue Plan funding to provide premium pay (also called “hazard pay”) for low-wage essential workers.

- This breaks down to just 2% of funds allocated to Midwestern states being used for premium pay. Essential workers deserve better.

The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) presents a historic opportunity for state and local governments to shape their region’s economic recovery and also address the long-standing inequities that the pandemic continues to expose and worsen. One straightforward way that ARPA money could be used to combat these inequities is boosting the wages of the disproportionately Black and Brown workers and women who have been on the front lines of the public health and economic crisis. However, few Midwestern states have opted to do so; data on states’ allocation of ARPA funds thus far show few resources being put towards premium pay.

ARPA allocated $195 billion in fiscal recovery funds directly to states, with billions more also directed to counties, cities, tribal governments, and other units of local government. Interim rules developed by the Department of the Treasury designate four allowed uses for ARPA funds: including investments for infrastructure; assistance to households, small businesses, and nonprofits, and industries impacted; propping up state government services impacted by tax shortfalls; and premium pay.

Among the four uses, premium pay in particular would help lift up marginalized workers impacted by the pandemic. Premium pay” (also sometimes called hazard pay, even sometimes called “hero pay” by businesses) for workers “in critical infrastructure sectors who regularly perform in-person work, interact with others at work, or physically handle items handled by others.” This includes jobs in child care, health care, grocery stores, meat processing, transportation, and public health.

Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey reflects a decline in both job openings and hires after Delta variant surge

Below, EPI senior economist Elise Gould offers her initial insights on today’s release of the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) for August. Read the full Twitter thread here.

The fall in job openings and hires for August is consistent with the #JobsReport for the same month and the uptick in separations (due to an increase in quits) is not surprising as covid caseloads increased about five fold between July and August. pic.twitter.com/3b0r194qFw

— Elise Gould (@eliselgould) October 12, 2021

Weak job growth in September as Delta variant leaves its mark

Below, EPI economists offer their initial insights on the September jobs report released today. After a relatively weak August, only 194,000 jobs were added in September.

Cutting the reconciliation bill to $1.5 trillion would support nearly 2 million fewer jobs per year

Congress may have bought itself another month to negotiate over the Biden-Harris administration’s Build Back Better (BBB) agenda, but one thing is clear: Further reducing the scale and scope of the budget reconciliation package unequivocally means the legislation will support far fewer jobs and deliver fewer benefits to lift up working families and boost the economy as a whole.

How much will such compromise cost the U.S. economy? We crunched the numbers to find out what compromising on the BBB plan will mean for every state and congressional district in the United States. If the budget reconciliation package is cut from $3.5 trillion to $1.5 trillion—as Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.V.) has called for—nearly 2 million fewer jobs per year would be supported.

What to watch on jobs day: A seasonal swing in public-sector education employment

On Friday, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) will release September’s numbers on the state of the U.S. labor market. August employment growth came in lower than June or July due in part to the Delta variant spreading quickly. Another sign of weakness in the August job report was the rise of Black unemployment, which remains significantly higher than other groups. The August jobs report showed us, once again, just how much the ebbs and flows of the pandemic are the dominant influence by far on trends in the labor market.

This pronounced August slowdown also came after more than half of all states prematurely ended the pandemic unemployment insurance (UI) programs. All of the pandemic programs ended in early September.

While no longer accelerating, COVID-19 caseloads were still high in mid-September compared with the early summer months, so that may once again slow the recovery. In this jobs report, one indicator I’m going to be paying close attention to is public-sector employment, specifically public-sector education employment.

Overall government employment is still down 790,000 jobs since February 2020—the third largest employment deficit in any economic sector—but this shortfall is entirely in state and local employment and much of those losses were in education employment. Local education employment—think the public K-12 school system—cratered in the spring of 2020, experiencing losses in excess of those suffered in the Great Recession and, as of mid-August, remained 219,600 short of its pre-pandemic level.

Abolish the debt ceiling before it commits austerity again: The GOP used the debt ceiling to force spending cuts in 2011. It can’t be allowed again.

In a political system beset by many stupid and destructive institutions, the statutory limit on federal debt might be the worst. The debt limit:

- Measures no coherent economic value. The measure of debt it targets is not inflation-adjusted, would perversely make the debt situation look worse if there was a reform to Social Security that closed that program’s long-run actuarial imbalance, and ignores trillions of dollars in assets held by the federal government.

- Has no relationship to any economic stressor facing the country. Over the past 25 years, as the nominal federal debt rose from $5 trillion to $22.7 trillion, debt service payments (required interest payments on debt) shrank almost in half, from 3.0% of GDP to 1.8%.

- Can cause real damage if it’s not lifted in the next couple of weeks. It would only take a couple of months of missing federal payments due to the debt ceiling to mechanically send the economy into recession—and that’s without assessing damage it would cause from financial market fallouts.

- Has been used time and time again to enforce misguided austerity policies. The 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA) grew directly out of a GOP Congress threatening to not raise the debt ceiling absent spending cuts. The BCA provided an anti-stimulus about twice as large as the stimulus provided by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA—commonly known as “The Recovery Act”) and is largely responsible for the sluggish recovery from the Great Recession.

Given all of this, the debt ceiling should be abolished or neutralized in absolutely any way politically possible. It serves no good economic purpose and plenty of malign ones. Below we expand on these points.

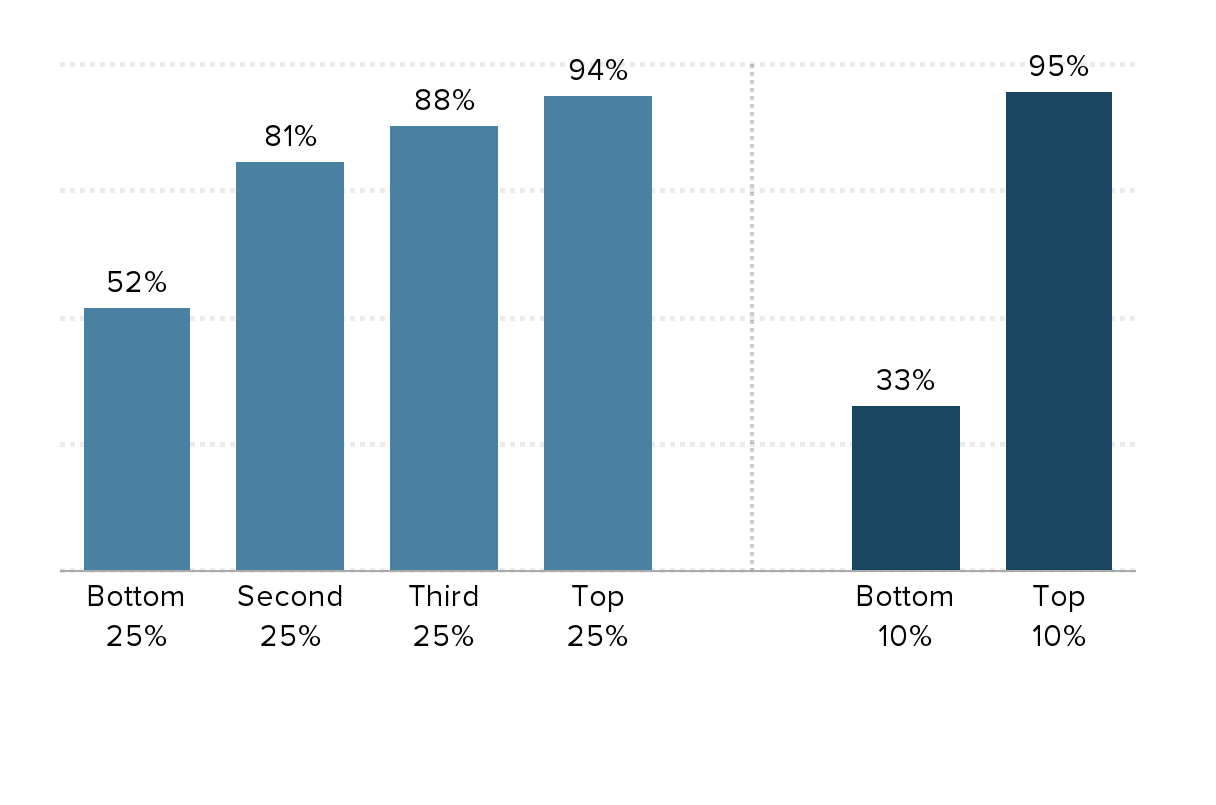

Two-thirds of low-wage workers still lack access to paid sick days during an ongoing pandemic

According to a new report released yesterday from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), just over three-quarters (77%) of private-sector workers in the United States have the ability to earn paid sick time at work. But, as shown in Figure A below, access to paid sick days is vastly unequal, disproportionately denying workers at the bottom this important security. The highest wage workers (top 10%) are nearly three times as likely to have access to paid sick leave as the lowest paid workers (bottom 10%). Whereas 95% of the highest wage workers had access to paid sick days, only 33% of the lowest paid workers are able to earn paid sick days.

Low-wage workers are also more likely to be found in occupations where they have contact with the public—think early care and education workers, home health aides, restaurant workers, and food processors. Workers shouldn’t have to decide between staying home from work to care for themselves or their dependents and paying rent or putting food on the table. But that is the situation our policymakers have put workers in. Meaningful paid sick leave legislation is incredibly important for low-wage workers and their families and important to reduce the spread of illness. At the same time, access to paid sick days has positive benefits to employers as it reduces employee turnover with no impact on employment.

High-wage workers have paid sick days; most low-wage workers do not: Share of private-sector workers with access to paid sick days, by wage group, 2021

| Category | Share of workers who have access to paid sick days |

|---|---|

| Bottom 25% | 52% |

| Second 25% | 81% |

| Third 25% | 88% |

| Top 25% | 94% |

| Bottom 10% | 33% |

| Top 10% | 95% |

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Compensation Survey 2021