What this report finds: In recent years, cities, counties, and other localities have become innovators and leaders in standing up for working people. A number of localities have come to view protecting workers and improving their working conditions as part of their core municipal function. Some of the most noteworthy ways in which localities have taken action on behalf of working people in recent years include:

- establishing dedicated local labor standards offices that enforce workers’ rights laws

- establishing ongoing worker boards or councils

- passing local worker protection laws

- actively enforcing local worker protection laws

- setting job quality standards for contractors with the municipal government

- establishing legal consequences for labor violations among applicants for municipal permits or licenses

- practicing high-road employment principles in relation to municipal employees

- championing worker issues through public leadership

While other reports have done an excellent job of exploring local action on specific issues like paid sick leave, living wages, and creation of worker boards, this report identifies and examines the broader trend of increased local action and analyzes the landscape of cities and other localities’ pro-worker actions in a comprehensive way.

Why it matters: Policies and enforcement that protect the rights of workers, ensure workers are able to meet their basic needs, and support workers’ efforts to organize are foundational to building healthy, thriving, and equitable communities. Working people in the United States today face multiple crisis situations that not only adversely impact their well-being, but also undermine the health and well-being of communities. Outdated labor laws are skewed against workers trying to form and join unions, and workers who try often face retaliation and other violations by employers. Public enforcement resources are inadequate, and workers are increasingly unable to bring their claims in court because of forced arbitration. In this context, cities and localities are vitally important and necessary actors in the effort to expand and enforce workers’ rights. They are close to their residents, and often are nimble and fast-moving in responding to emerging needs. A few cities (along with a few states) are also at the vanguard of innovating on policy and piloting new approaches to expanding and protecting workers’ rights. There is very meaningful work currently happening at the local level, with untapped potential for much more local action.

What can be done about it: Local policymakers, enforcers, advocates, and community members can work together to pilot new local laws, create dedicated labor enforcement agencies and worker boards, develop strategic community enforcement partnerships, and use permits to drive compliance. Localities can fight abusive state preemption that impairs the abilities of local governments to build upon minimum standards set at the state level. Unions, worker advocates, and the public can think creatively about how to enact measures within their own localities and press for action. Other actors and observers in this space—federal and state government, the media, funders, academics, and more—should develop a greater understanding of the emerging role of cities in protecting working people. They should work to institutionalize and chronicle protecting and supporting workers as part of our understanding of what localities do. This report offers a road map of opportunities to enact policies at the local level that advance workers’ rights and improve working conditions.

Executive summary

In recent years, cities, counties, and other localities have become innovators and leaders in standing up for working people. Responding to increased inequality, degraded working conditions, and insufficient or inconsistent worker protections at the state and federal level, localities have in many cases joined states as the “laboratories” of experimentation (as Supreme Court Justice Louis D. Brandeis described) in relation to workplace matters.1 A number of localities have come to view protecting workers and improving their conditions as part of their core municipal function.

![]()

This is a joint project with the Harvard Law School Labor and Worklife Program and Local Progress.

This report provides an overview of some of the most noteworthy ways in which localities have taken action on behalf of working people in recent years:

- Some localities have established dedicated local labor standards offices that enforce workers’ rights laws; educate employers, workers, and the public about these laws; and in some cases help formulate or inform municipal policy in this area.

- Localities have established ongoing worker boards or councils to provide workers with a formal role in local government and/or access to local officials and agencies.

- Other localities have focused on passing local worker protection laws, including ordinances regarding minimum wages, paid sick leave, and fair scheduling; industry-specific protections for sectors with high violation rates or specific vulnerability (such as the domestic worker, gig, hotel, retail, fast-food and freelance industries); broader anti-discrimination protections; and specific laws responsive to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Localities are actively enforcing local worker protection laws, including with funded community partnership models in some instances.

- Some localities have established job quality standards for contractors, while others have established legal consequences (including denial and revocation) for applicants for initial or renewed municipal permits or licenses who have a history of wage theft violations or unresolved labor standards orders.

- Localities are demonstrating how to be a high-road employer of municipal employees, including by incorporating labor standards like higher minimum wages and paid sick leave, and enabling or facilitating collective bargaining among workers in local government.

- Active localities and local elected and appointed government leaders are exerting leadership in the public sphere, through education and outreach about labor laws, issuance of reports, convenings and public hearings, and use of the bully pulpit.

Federal—and in some cases state—preemption creates some limitations on what localities can do to expand and protect workers’ rights. Preemption occurs when federal or state law prevents subordinate levels of government (in this case, municipalities) from legislating or acting on a given issue. Still, local governments have considerable opportunity to take meaningful action on behalf of the working people within their jurisdictions.

The time is ripe for local action to advance workers’ rights. Working people are expressing dissatisfaction with worsening working conditions by resigning, forming and joining unions, and demanding change.

Overview and introduction

Policies and enforcement that protect the rights of workers, ensure that workers are able to meet their basic needs, and support workers’ efforts to organize are foundational to building healthy, thriving, and equitable communities (Bhatia et al. 2013; USC ERI 2020). Working people in the United States today face multiple crisis situations that not only adversely impact their well-being, but also undermine the health and well-being of communities. The COVID-19 pandemic has led to many workplace clusters. Federal and state workplace measures have been varied, yet insufficient, to provide adequate protection from the virus.

Even before the pandemic, working people had been experiencing a multitude of serious challenges. Two widespread challenges are wage theft—the practice of employers failing to pay workers the full wages to which they are legally entitled—and misclassification of workers as independent contractors—the practice of employers labeling workers as independent contractors, rather than employees, to avoid paying unemployment and other taxes on workers and covering them with workers’ compensation insurance. Outdated labor laws are skewed against workers trying to form and join unions, and workers who try often face retaliation and other violations by employers (McNicholas 2019). Public enforcement resources are inadequate, and workers are increasingly unable to bring their claims in court because of forced arbitration (Hamaji et al. 2019). Employers who fail to pay unemployment or other taxes deprive public coffers of resources needed for programs serving important human needs (Erlich 2019). Meanwhile, the labor market itself is skewed—workers’ wages have not kept up with their productivity (Mishel 2021), and corporate concentration along with anti-competitive practices add to workers’ challenges in getting a fair wage (Stansbury 2021). These challenges have fallen hardest on workers of color and workers in low-wage industries.

Federal and state leaders who wish to take action on these thorny and deep-seated issues often face significant obstacles when they seek to pass laws, promulgate regulations, or take other steps responsive to workers’ needs. Such challenges can be even greater in relation to emerging developments in the workplace.

Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis famously described states as laboratories of public policy experimentation.2 In relation to workers’ rights, U.S. localities3 have been true laboratories of experimentation in recent years (Diller 2014).4 Historically, the federal government and states have been responsible for workplace regulation; over the years, cities and localities have not generally taken a leading role.5 But in roughly the past decade, cities and localities have become increasingly important actors in expanding and enforcing workers’ rights—what some commentators have called the “municipalization” of labor law (Sarchet 2021).

The District of Columbia

Although the District of Columbia is a city and has passed notable workers’ rights laws in recent years, it is not included in this report because of how it operates in relation to the subjects discussed here. Specifically, it operates more like a state than a city. It has long had an agency, the Department of Employment Services (DOES), that fulfills the functions that state labor departments or agencies typically do within states: administering the district’s unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation programs, implementing workforce development and employment services programs, researching labor statistics, offering onsite workplace safety and health consultations to private employers, and enforcing the district’s labor standards laws.

Cities and localities have introduced cutting-edge laws that do not exist at the federal or state level (including some responsive to newly emerging problems); established new offices devoted to protecting workers; used their contracting, licensing, and permitting powers to drive employer compliance; and implemented new methods of enforcement, including close and even funded partnerships with worker and community organizations. Such action by localities has occurred not only in traditionally worker-friendly regions, but also in progressive cities located within more conservative states. (Efforts in such locales have often, but not always, been met with state-level preemption measures, as noted by Blair et al. 2020 and Wolfe et al. 2021). And in some cases, such as the expansion of paid sick days, policy leadership at the local level has provided proof of concept and helped build momentum for states (and earlier in the pandemic, even the federal government) to take action. Local government action on workers’ rights also often reflects efforts to address local conditions when it comes to cost of living, dominant and emerging industries, and the needs and organizing of specific communities (especially communities of color and immigrant communities).

This report provides both an outline and a road map: an outline of actions that cities and localities have taken in recent years to protect workers, and a road map of possible policy and enforcement options for local leaders, both elected and appointed, to consider.6 Such actions include:

- establishing a dedicated department, office, or subagency within city government focused on worker issues

- creating boards or councils that provide workers with a voice, a role, and/or access to local government

- passing laws that create new and essential rights for workers

- enforcing worker protection laws, including through strategic, innovative, and/or collaborative approaches

- leveraging contracting, licensing, and/or permitting powers to raise and address worker issues

- incorporating high-road employment practices and labor policies in relation to their own municipal workforces

- using soft powers, including community education and outreach, issuance of reports, and other “bully pulpit” vehicles for reaching the community and highlighting worker needs and available resources

Notably, some cities and localities have taken meaningful action to protect workers and advance their rights and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic; more should follow suit. This report also outlines a number of measures taken at the local level in response to COVID-19.

This report is intended not only for local leaders, but also for labor unions and worker advocates, to help deepen their understanding of policy and enforcement levers at the local government level in order to guide advocacy and collaborative governance efforts. This report can also inspire academics and other researchers to study local efforts to advance workers’ rights. Finally, policymakers at all levels of government should pay attention to the innovative solutions advanced by localities.

At least 20 localities have created or are creating dedicated local labor agencies

A number of localities have created agencies specifically dedicated to enforcing workers’ rights under local ordinances, including laws addressing minimum wages,7 wage theft, paid sick and safe leave, fair scheduling/fair workweek requirements requiring advance notice of scheduling, fair chance hiring laws, gig worker rights, and more. Several of these agencies are also charged with analyzing and potentially proposing local labor policies. In other instances, localities do not have a dedicated stand-alone office, but units of other municipal agencies focus specifically on workers’ rights matters. And some localities without dedicated units have tasked specific government entities with enforcing wage theft or paid sick leave laws, such as a city manager, treasurer, or attorney; office of human rights; unit of the mayor’s office; or other officials (A Better Balance n.d.b.; Boulder 2022; Pinellas OHR n.d.; Miami-Dade WTP n.d.).8

Creation of a dedicated unit within local government focused on workers’ rights can be transformative. It ensures that municipal public servants will be involved in worker protection in a continuous, proactive, ongoing, and in-depth manner. It allows specialized staff to develop expertise on the relevant municipal laws and policies, as well as deep knowledge of issues affecting local workers. Where there is a dedicated worker-focused office in local government, staffers can develop ongoing relationships with relevant stakeholders like worker advocacy groups, unions, immigrant rights advocates or service providers, employment lawyers, and employer associations, as well as other relevant government enforcement agencies at the local, state, and federal levels. A dedicated office also can be mobilized to address emerging needs, including those that arose in the COVID-19 pandemic. Most importantly, establishment of a dedicated office institutionalizes and embeds the work within local government, ensuring the focus on workers and their challenges will continue beyond a particular administration.

Jurisdictions with dedicated agencies, subdivisions, or staff include Berkeley (California), Boston, Chicago, Denver, Duluth (Minnesota), Emeryville (California), Flagstaff (Arizona), Los Angeles City, Los Angeles County, Minneapolis, New York City, Philadelphia, San Francisco, San Jose, Santa Clara County (California), Seattle, St. Paul (Minnesota), and Tacoma (Washington).9 In addition, the San Diego County Board of Supervisors voted in 2021 to create a county labor office, and the San Diego City Council followed suit in 2022 by voting to create a labor enforcement office in a new Compliance Department.10 Tucson, Arizona, voters in 2021 passed a ballot initiative to create a local minimum wage and also a city Department of Labor Standards.11 Numerous Florida localities have created wage theft enforcement or mediation programs of various kinds: Broward County (complaint form), Miami-Dade County, and Pinellas County.12 Via court order, Palm Beach County created a Wage Dispute Division within the county civil court.13

More dedicated units to enforce workers’ rights are likely on the horizon. For example, a legislative proposal resulting from the work of an Earned Sick and Safe Leave Task Force is currently under consideration in Bloomington, Minnesota (population of approximately 90,000), home of the Mall of America.14 The city manager there has stated that two full-time equivalent staffers (one attorney and one paralegal) would be needed for this work.15

Snapshots of several local agencies in cities of varying size:

Berkeley, California (Pop. 124,321): The Workplace Enforcement and Standards Unit was created in 2014. It currently has a single full-time equivalent (FTE) employee, who also holds nonlabor-related responsibilities in addition to enforcing the city’s minimum wage, living wage, paid sick leave, and other laws (U.S. Census Bureau 2022a).

Chicago (Pop. 2.7 million): Chicago’s Office of Labor Standards, housed in the Department of Business Affairs and Consumer Protection, began operating in 2019 (its official launch date was in 2020). As of June 2022, the office has eight FTEs. It enforces the city’s minimum wage, wage theft, paid sick leave, fair workweek, COVID and vaccine anti-retaliation laws, as well as a law effective in January 2022 requiring employers of domestic workers to provide them with written contracts (U.S. Census Bureau 2022b).

Denver (Pop. 715,522): Denver Labor, created in 2019, is a division enforcing wage and hour laws located in the Denver auditor’s office. The office has 25 FTEs, and it enforces the city’s minimum wage laws, as well as a number of laws related to government work: a minimum wage applicable to city contractors, the city’s prevailing wage, the city’s living wage, and more. The office also has a community education emphasis: there are full-time community education staff and an annual outreach/education plan, including radio and internet ads, weekly online training, hundreds of outreach events, and multilingual written materials (U.S. Census Bureau 2022c).

Duluth, Minnesota (Pop. 86,697): Enforcement of Duluth’s earned sick and safe time law (effective in 2020) is handled through the equivalent of one employee housed in the city clerk’s office (U.S. Census Bureau 2022d).

Los Angeles City (Pop. 3.9 million): The Office of Wage Standards in the city of Los Angeles was created in 2015. It is authorized to have 30 FTEs, although in February 2022, this figure included nine vacancies. It enforces the city’s minimum wage, paid sick leave, and fair chance hiring laws (U.S. Census Bureau 2022f). (The county of Los Angeles has a separate enforcement agency that enforces the county’s own workplace laws.)

Minneapolis (Pop. 429,954): The Labor Standards Enforcement Division was created within the city’s Department of Civil Rights in 2016. The office has five FTEs, and it enforces the city’s paid sick and safe time, minimum wage, wage theft, and freelance worker protections laws, as well as a law giving hospitality workers the right of recall, which will sunset one year after the COVID-19 public health emergency (U.S. Census Bureau 2022g).

New York City (Pop. 8.8 million): New York City’s Office of Labor Standards and Policy was created in 2016, and is housed in the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (DCWP). (That agency was long known as the Department of Consumer Affairs; its name changed in 2019 (Greenbaum 2019) in part to convey the agency’s focus on workers as well as consumers.) In 2021, the office had 33 FTEs. While it lacks jurisdiction to set a city minimum wage, the office enforces the city’s Paid Safe and Sick Leave Law, Freelance Isn’t Free Act, and the Fair Workweek Law in retail and fast-food, as well as several new cutting-edge laws, including a “just cause” termination law giving fast-food employees protections against arbitrary termination, and a law giving food delivery workers greater control over their working conditions and authorizing DCWP to set a minimum pay rate (U.S. Census Bureau 2022h).

Philadelphia (Pop. 1.6 million): In the June 2020 primary election, voters of Philadelphia overwhelmingly approved a ballot question to amend the city charter to create a city department of labor, demonstrating widespread public support for municipal involvement in workers’ rights issues (U.S. Census Bureau 2022i; Ballotpedia n.d.). The head of the Philadelphia Department of Labor is the deputy mayor for labor, holding a high-profile position within city government. The Office of Worker Protections, located within the department, has a total of nine FTEs, and enforces wage theft, paid sick leave, and fair workweek laws; laws covering specific industries (domestic worker bill of rights, wrongful discharge of parking employment, recall and/or retention of hotel, travel and hospitality workers); and more. The office established a domestic worker task force and has been tasked with creating a portable benefits system for domestic workers (Orso 2020), likely to be the nation’s first. In addition, in 2020 and 2021, the office partnered with worker organizations on a citywide effort on the Philadelphia Worker Relief Fund (MF Phila. n.d.; Cox 2020), which distributed more than $2.2 million to 2,820 families left out of COVID-19 government relief (Philadelphia 2020a). The office also collaborated on a referral system with the city health department’s COVID-19 containment unit to mediate paid sick leave when workers reported exposure.

San Francisco (Pop. 873,965): San Francisco’s Office of Labor Standards Enforcement (OLSE) was created nearly 20 years ago (San Francisco n.d.a; SF OLSE n.d.e). The office has 30 FTEs, and currently enforces more than 30 citywide laws, including ordinances on minimum wage, paid sick leave, fair chance employment, scheduling laws, and others, as well as a handful of other laws related to government contracting (SF OLSE n.d.f; U.S. Census Bureau 2022j).

San Jose (Pop. 983,489): San Jose’s Office of Equality Assurance, with a staff of eleven, implements, monitors, and administers the city’s wage policies, including the living wage law applicable to city service contracts, the prevailing wage law which covers public works (construction) projects, and the minimum wage ordinance applicable to employers for work performed within the city. The Office also contracts with a number of neighboring localities to provide minimum wage enforcement services for their own local minimum wages. For example, in 2020, the City of San Jose entered into contracts with the nearby cities of Burlingame, Cupertino, Milpitas, Redwood City, San Carlos, San Mateo, Santa Clara, South San Francisco, and Sunnyvale; maximum compensation under the contracts is $40,000 to $45,000 to cover a period of two and a half to three years. This arrangement allows smaller localities to functionally pool resources in order to have their local laws enforced (San Jose 2020; San Jose n.d.; U.S. Census Bureau 2022k).

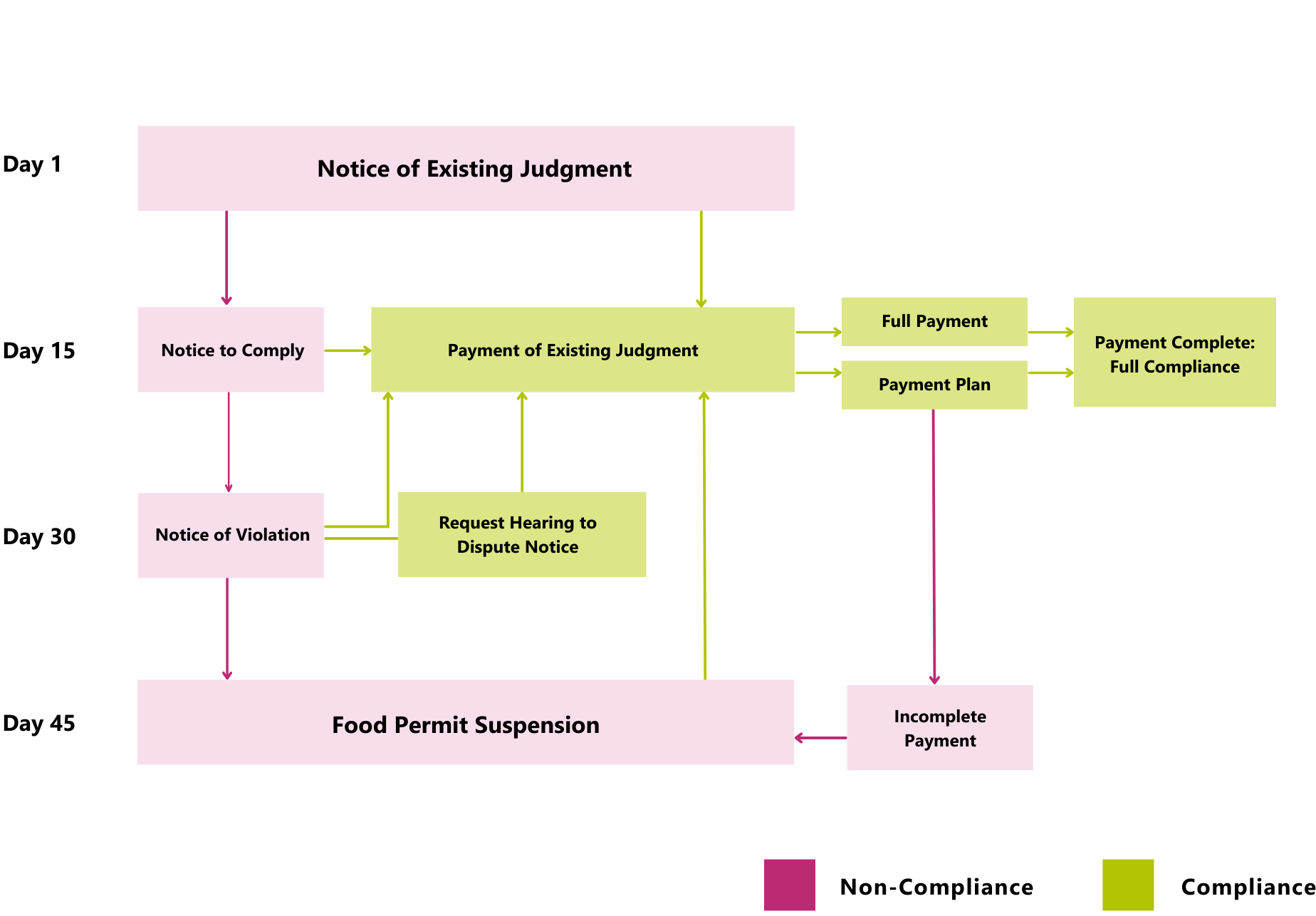

Santa Clara County, California (Pop. 1.9 million): The County’s Office of Labor Standards Enforcement was created in 2017. The office has capacity for five FTEs; four were filled as of May 2022. Among other things, the office ensures that recipients of county permits, licenses, and contracts comply with labor laws and satisfy outstanding judgments issued by the California Labor Commissioner’s Office. The office also enforces wage theft prevention and living wage requirements related to contracting, contained in Chapter 5 of the Santa Clara Board of Supervisors Policy Manual (Section 5.5.5.4) (SC BOS 2020). In 2021, the office also enforced a hazard pay ordinance related to COVID-19 (SC OLSE n.d.c; U.S. Census Bureau 2022l).

A deeper dive into Seattle’s local labor agency

Seattle’s Office of Labor Standards has grown rapidly since its creation in 2015 as a division within the Seattle Office of Civil Rights. The Office of Labor Standards became an independent, standalone city agency in 2017, and the breadth and impact of its activities provide a useful example of the potential of municipal labor agencies.

Staffing: As of February 2022, the office had 34 FTEs and one full-time temporary position. These position include a director, deputy director, communications manager, seven outreach positions, four policy-focused positions, three operations and finance positions, and eighteen enforcement officials.

Ordinances: The office enforces 18 city laws. These include laws of broad application (paid sick and safe time, fair chance employment, wage theft, and commuter benefits ordinances); laws targeting specific industries (secure scheduling ordinance for retail and food services workers, as well as ordinances protecting domestic workers, transportation network company drivers, and hotel workers); and laws enacted during the COVID-19 pandemic (paid sick and safe time for gig workers, as well as premium/hazard pay for gig workers/grocery employees) (Seattle OLS 2012, 2013, 2015a, 2015b, 2017, 2020b, 2020d, 2020e, 2020h, 2021a). Finally, on September 1, 2022, the Independent Contractor Protections Ordinance (Seattle OLS 2021b) will take effect; it will require commercial hiring entities to provide certain precontract disclosures and payment disclosures, and also requires timely payment of contracts. See Section 6 for more in-depth discussion.

Enforcement: The office has brought a number of successful enforcement actions, including in fast-food, gig economy, construction, retail, grocery, and other industries. These cases are described in Section 7.

Policymaking: The office has helped develop city labor policy in various ways. The office ran a broad policymaking process to develop two labor standards ordinances for transportation network companies (TNC) drivers, including contracting for a minimum compensation standard study (Reich and Parrott 2020). The office conducted an extensive stakeholder process and drafted the eventual TNC Driver Minimum Compensation Ordinance (Seattle OLS 2020i), which went into effect in 2021 and the TNC Driver Deactivation Rights Ordinance (DRO). The DRO provides drivers protection against unwarranted termination from companies’ platforms, a pathway to resolve deactivation disputes before a neutral arbitrator, and which created a first-in-the-nation Driver Resolution Center to provide consultation and direct representation to drivers facing deactivation, along with culturally relevant outreach and education, and other support. The Office of Labor Standards completed a request for proposal to award an 18-month contract for just more than $5 million to a community organization to get the Driver Resolution Center up and running (Seattle OLS n.d.h).16

In addition, pursuant to a city council resolution and recommendation by the city’s Domestic Workers Standards Board,17 the Office of Labor Standards will be crafting a proposal for portable paid time off for domestic workers.

Pandemic response: The Office of Labor Standards has taken numerous actions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In April 2020, following amendment of the city’s Paid Sick and Safe Time Ordinance (PSST) to expand PSST uses in response to COVID-19, the office conducted emergency rulemaking to ease the burden of verification for use of PSST on workers and the health care system. The office provided updated information in more than 11 languages and, with the city’s Department of Neighborhoods, increased access to this information through audio and video recordings, as well as through trainings and town hall meetings. Responding to the increase of domestic violence during the pandemic, the office also partnered on a safe leave training with a local community organization, API Chaya, and the Mayor’s Office on Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault.

The office also assisted in distribution of food vouchers and masks via community-based organizations, including the office’s Community Education and Outreach Fund partners, to workers who experienced structural or institutional barriers to accessing support from government (e.g., language barrier, fear of deportation, experienced domestic violence, did not qualify for other benefits). The community-based organizations enrolled more than 800 workers who had lost their jobs or experienced a decrease in hours or wages due to the pandemic. Each worker received $1,920 in grocery vouchers over a seven-month period.

Finally, along with the mayor’s office and the Office of Immigrant and Refugee Affairs, the Office of Labor Standards worked to increase access to unemployment funds for workers, especially for potentially misclassified gig workers and domestic workers, and also to enhance access to information about unemployment benefits in multiple languages. One effort included contracting with a community organization for three months to provide cultural- and language-specific outreach and referral assistance to transportation network company, taxi, and for-hire vehicle drivers seeking to access COVID-19-related relief resources. The community organization assisted 1,400 workers with their unemployment insurance claims in 12 languages, including Kiswahili, Nuer, Twi, and Hausa. Another effort included partnering with a local civil legal aid organization to provide training on unemployment insurance, and paid sick and safe time.

Several cities have created boards or councils to provide workers with a formal role and/or access to local government

Workers’ boards are bodies established by governments that include worker representation and that typically aim to provide workers with a voice and formal role in setting higher minimum standards for jobs in particular industries. These boards typically investigate challenges facing workers by conducting hearings and outreach activities, issuing reports on findings, and making recommendations regarding minimum wage rates, benefits, and workplace standards. By focusing on workers in specific industries, these boards are able to address industry-specific issues and involve workers and their organizations directly in governance decisions.

Professor Arindrajat Dube, based on his analysis of industry-specific wage boards in Australia, concludes that wage-setting boards “are much better positioned to deliver gains to middle-wage jobs than a single minimum pay standard” (Dube 2018); the local boards described here do not have wage-setting powers, but some may make recommendations. In 2019, the Center for American Progress issued a how-to guide for state and local governments and advocates interested in developing workers’ boards or similar structures (Andrias, Madland, and Wall 2019). The guide’s detailed recommendations include ensuring a broad mandate; requiring representative and democratic selection of members; granting boards authority to gather relevant information through hearings and investigations; granting boards authority to issue recommendations; creation of strong enforcement mechanisms to ensure compliance with new standards; and empowering worker participation in board activities by requiring employers to provide reasonable time to participate and compensating workers for their participation, among other things.

In some states, preemption of local wage or standard-setting limits potential recommendations a board could make that would result in material policy change; however, even then, workers’ boards may be able to impact local government purchasing and contracting policies, workforce development programs, tax abatement and incentive policies, economic development planning and community benefits agreements, distribution of local government funding, and workplace safety trainings. They may also be able to provide independent monitoring of local, state, and federal public health and labor laws, and inclusive economic development planning. Worker boards are a relatively new development, mostly established in the last five years.

The following are examples of several local worker boards or similar structures:

Seattle Domestic Workers Standards Board: In 2019, Seattle passed the Domestic Workers Ordinance, which along with establishing a minimum wage and entitling workers to rest and meal breaks, also created a Domestic Workers Standards Board (Seattle CC 2018). The board, members of which are appointed by the mayor and city council (and one member is appointed by the board itself), requires representation from domestic workers (including workers who are and are no members of worker organizations), employers, and the community (with an emphasis on vulnerable populations like people with disabilities) (Seattle OLS 2018a). The board is empowered to provide recommendations to the city council on workplace safety standards, discrimination and sexual harassment, training for workers and employers, access to leave, wage standards, workers’ compensation, hiring agreements, and other topics, and has been granted funding to implement these recommendations.

Detroit Industry Standards Boards: Detroit passed an ordinance in November 2021 creating a structure for industry standards boards (SEIU Healthcare 2021; Detroit 2021). A standards board in a specific industry can be established under the ordinance by the city council, at the request of the mayor, or by petition of at least 225 workers in a given industry. The standards boards are composed of workers, employer representatives, and other individuals appointed by the mayor and city council. The industry boards are tasked with investigating industry conditions, conducting outreach to workers, making recommendations as to pay, benefits, training opportunities and scheduling, and forwarding complaints to relevant enforcement agencies.

Harris County (Texas) Essential Workers Board: Harris County established an essential workers board in 2021 to advise the county on programs and policies that support essential workers. All members must be “low-income essential workers,” with at least one worker representative from each of the following essential industries: airport or transportation; construction; domestic work or home care; education or child care; grocery, convenience, or drug store; health care or public health; janitorial; food services, hospitality, or leisure services; and retail (Trovall 2021; Harris County 2021). In addition to advising the county on its overall approach to protecting essential workers’ rights and providing a public forum, the board is also tasked with providing feedback on the county’s “purchasing and contracting policies, workforce development programs, tax abatement and incentive policies, community benefits agreements, distribution of federal COVID-19 relief and recovery funds, disaster preparedness and recovery programs, OSHA trainings, independent monitoring of local, state, and federal public health and labor laws, and inclusive economic development planning.”

Durham (North Carolina) Workers’ Rights Commission: In 2019, Durham formed the Workers’ Rights Commission as an advisory body to the city council on working conditions in Durham. Except for a liaison to the city council, all members are workers appointed by the city council and must include workers from the largest employers in Durham, workers in low-wage industries, workers organized in unions, and unorganized workers. The commission aims to provide a public forum for discussion and exploration of workers’ rights, conduct studies, recommend pro-worker policies for the city council’s state legislative agenda, craft a workers’ bill of rights and develop a voluntary recognition program to reward employer compliance, propose standards to encourage all employers within the city to establish a minimum standard, support workers in union campaigns, and provide channels of communication between organized and unorganized workers (Durham WRC n.d.).

Twin Cities’ Workplace Advisory Committees: In 2016, Minneapolis created a Workplace Advisory Committee in connection with passing the city’s safe and sick time ordinance (Minneapolis 2016a). The committee is composed of representatives from organized labor, workers, and employer representatives, among others. The committee is tasked with providing advice on workplace initiatives, recommendations on community engagement, and monitoring and evaluating implementation of workplace policies (Minneapolis 2016a). St. Paul’s Labor Standards Advisory Committee (St. Paul n.d.a) advises and supports the city’s Labor Standards Enforcement and Education Division. The committee includes representatives of employers, employees, and the public, and advises in the development and implementation of policies, procedures, and rules related to the city’s minimum wage and earned sick and safe time ordinances; recommends actions to improve strategic community outreach and education efforts; supports strategic enforcement and strategic outreach; explores and recommends opportunities and resources to help small businesses; assists with community partnerships; and engages business owners, workers, and community stakeholders to gather feedback and recommendations.

Los Angeles County Public Health Councils (LA PHC n.d.): In November 2020, Los Angeles County approved a program establishing public health councils to help ensure that employers follow COVID safety guidelines. Implemented and overseen by the county’s Department of Public Health, the program empowers workers to form public health councils at their worksites to monitor compliance with county health orders in the following industries: food and apparel manufacturing, warehousing and storage, and restaurant (LA County BOS 2020). The Department of Public Health will enlist the help of certified worker organizations to conduct outreach and education to workers interested in forming public health councils.

Localities can serve as model employers in relation to their own workforces

Localities can support working people by creating good working conditions for their own municipal workforces. Nationally, about one-third of state and local employees are paid less than $20 per hour, and more than 15% are paid less than $15 per hour. In 13 states, more than 20% of state and local workers are paid less than $15 per hour (Sawo and Wolfe 2022). Women and Black workers are more likely to be employed by local and state governments, so improving working conditions for local government workers advances important equity goals (Cooper and Wolfe 2020).

A significant portion of local government employees are union members (40.2% in 2021) (BLS 2022); high unionization rates among law enforcement and teachers contribute to these numbers. Working conditions for these employees are established through collective bargaining agreements with the locality. Working conditions of nonunionized municipal workers are governed by applicable federal, state, and local laws, as well as municipal policy.

Localities can support workers by raising labor standards for their own employees regardless of union membership. They can also take steps to allow and facilitate collective bargaining by their employees.

Limited public funds can lead to concerns about the cost of supporting municipal workers in light of other pressing public funding needs. However, in addition to improving municipal job quality as a matter of values and commitment to working people, localities themselves can benefit from doing so. High-road job offerings can help attract better-qualified workers to local government and reduce turnover, both of which enable local governments to provide higher-quality public services, as well as avoiding the cost associated with employee turnover. Municipal employers are often the largest employers in many regions (Hain and Coffin 2020), and thus improved standards for municipal workers can also lead to additional benefits, like public health gains when paid sick leave prevents spread of illness, and stabilizing and stimulating the local economy in times of stagnation or recession. By exemplifying practices of a model employer, local governments also can play a leadership role for private and nonprofit employers, helping create local norms that lift local working standards generally. And collective bargaining in particular can help reduce racial and gender pay gaps, attract workers to local government, and create high-quality jobs (Morrissey and Sherer 2022).

Local governments can also support municipal workers by limiting and resisting privatization, defined as the shifting of governmental functions and responsibilities to the private sector through such activities as contracting out (Local Progress 2019). Privatization of local government functions has proliferated in the recent past, affecting services and infrastructure like water treatment, trash collection, and toll collection (Early 2021; Dutzik, Imus, and Baxandall 2009). Privatization not only denies opportunities to municipal workers who are more likely to be unionized and to have higher job standards, it also undermines democratic accountability. Moreover, projected cost savings from privatization often do not materialize, and service quality often declines under private provision (PWF n.d.b).18

Localities have raised labor standards for municipal employees

A number of localities have raised the minimum wage paid to their own municipal workforce; recent examples include Atlanta; Jersey City, New Jersey; Milwaukee; New Orleans; North Miami Beach, Florida; Tallahassee, Florida; and West New York, New Jersey (Noble 2021; Fox 2021a, 2021b; Atlanta 2017; Miami Times Staff 2021). More than 100 localities have passed paid family or parental leave policies for their municipal employees (NPWF 2020). Many local governments extended emergency paid sick leave to their municipal workers during the pandemic, and some front-loaded the annual sick leave allotment for all employees (Hain, Yadavalli, and Wagner 2020). The city of Austin distributed stipends to some city workers who continued to provide in-person services during the COVID-19 pandemic (Newberry 2020).

Localities can enable and support collective bargaining and union organizing by municipal workers

Localities also can enable or facilitate collective bargaining and unionizing among their municipal workforce. Public employee unions can be stable bargaining partners to local governments, promote labor peace, and ensure the delivery of high-quality services.19 In addition, unions reduce inequality as well as race and gender disparities (EPI 2021; Bivens et al. 2017) and boost democratic participation (McElwee 2015).

Whether or not local government workers can form and join unions varies by state and by the type of municipal worker. Many state statutes expressly authorize collective bargaining by teachers, police officers, and firefighters (Sanes and Schmitt 2014). In some states, local governments are permitted to collectively bargain with all municipal workers (Monroe 2018; Vermont 1973).20 In some states, local governments are prohibited from doing so.21 In states where collective bargaining for local employees is neither guaranteed nor prohibited by state law, localities can facilitate unionizing and collective bargaining by their own workforces by passing local ordinances permitting collective bargaining. Two states where there has been heightened attention to this issue in recent years are Virginia and Colorado. In Virginia, the General Assembly in 2020 passed a law lifting a previous ban, thereby allowing localities to recognize and collectively bargain with unions by passing an ordinance. A number of Virginia localities have since passed collective bargaining ordinances, including the city of Alexandria, Arlington County, Fairfax County, Loudoun County, and the Richmond School Board (Alexandria Magazine Living Staff 2021; Armus 2021; Olivo 2021; Loudoun 2021; Hunter 2021). In 2022, the Colorado state legislature passed a bill granting public employees the right to collectively bargain; previously localities could decide whether to grant such rights, and out of approximately 270 localities in the state, only 16 had collectively bargained contracts with any of their workers (Colorado General Assembly 2022; Miller 2022; Vo 2022; Kenny 2021). For example, Adams County, Colorado, had passed a resolution in 2017 authorizing collective bargaining for county employees.22 In states such as Colorado and Virginia, localities can explicitly grant their municipal workforce the right to collectively bargain. Cities like Louisville, Kentucky, Memphis, Tennessee, Salt Lake City, Utah, and Tulsa, Oklahoma, have recognized and entered into collective bargaining agreements with municipal unions (Louisville HR n.d.; AFSCME 1733 2021; SLC HR n.d.; Tulsa HR n.d.).

In addition, localities can emulate legislative measures taken by certain states to facilitate public employee union access to government workers in response to the Supreme Court’s decision in Janus v. American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, Council 31, et al. That case held that requiring public employees to pay union fair share agency fees to cover the costs of collective bargaining violates the First Amendment (McNicholas 2018).23 The decision bars unions from requiring workers who benefit from union representation to pay their fair share of that representation, thereby reducing public employee union resources and potentially their stability. In the wake of the Janus decision, a number of states, including California, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Washington, and several others, passed measures to reduce barriers to public-sector unionization, such as by requiring public employers to allow public employee unions access to new employee orientations, and to provide public employee unions with lists of new and current employees with contact information (NCSL 2019).

Finally, the 2022 Report of the White House Task Force on Worker Organizing and Empowerment (Harris and Walsh 2022) contains a number of recommendations for the federal government to increase unionization rates among federal employees. While some of the measures contained in the report would potentially be preempted by the National Labor Relations Act, many of them could be adopted readily by local governments, such as:

- facilitating exposure to unions during the hiring process for job applicants and onboarding process for new employees, including listing information about whether a position is in a bargaining unit and the relevant union in job opportunity announcements, and encouraging agencies to offer their unions more opportunities to communicate with new hires during onboarding

- developing guidance and labor relations materials for agencies to use in trainings for managers and supervisors regarding unfair labor practices and neutrality in union organizing campaigns

- increasing and visibly supporting workers’ right to organize, including a know-your-rights initiative on the right to organize and collectively bargain

The report contains extensive analysis and practical suggestions about ways to encourage and facilitate collective bargaining.

Localities have enacted worker protection laws on a range of topics

Local governments typically have some authority to initiate legislation, subject to their authority under the relevant state constitution, state statutes, and city charters. In recent years, local governments have increasingly used this power to pass laws to advance workers’ rights.24

Laws setting higher minimum wages

In recent years, localities have often led the nation in policymaking to raise workers’ wages. The Fight for 15 campaign and other worker advocates and organizations have played a key role in seeking increased local minimum wage floors, which has paved the way for more innovative policymaking to advance workers’ rights by local governments (Meyerson 2019).25 Local wage and hour laws exist in a statutory landscape, including the federal Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), which establishes a federal minimum wage, overtime pay, record-keeping, and youth employment standards, and state laws that similarly establish their own state-level minimum wage and hour standards. The FLSA, and in some cases state law, acts as a floor, permitting local governments to provide more generous protections for workers. Some states, however, preempt local governments from setting higher local requirements, as discussed in further detail below (EPI 2019).

Currently, 52 cities and counties have local minimum wage laws that raise the minimum wage above the level established by state and federal governments (UC Berkeley Labor Center 2022; Lathrop 2021).26 Local minimum wages aim to keep workers out of poverty and to increase consumer purchasing power to spur economic growth. Such wages sometimes are enacted in metropolitan areas where the costs of living are higher relative to the rest of the state or region. Local minimum wages may vary in terms of wage levels, implementation timelines, and exemptions (for example, based on the size or classification of an employer, such as employers with more than 25 employees or nonprofits). Since 2012, local minimum wage increases have affected more than 4 million workers, more than half of whom are workers of color, and generated more than $33 billion in additional income for these workers each year (Lathrop, Lester, and Wilson 2021).

One way to increase the wages of many service workers without setting a higher minimum rate is for a locality to disallow the lower minimum wage that is permitted in many states and under federal law for workers who customarily and regularly receive tips (USDOL 2022b). Tipped workers are more likely to be women and people of color, and more likely to be subject to sexual harassment (Schweitzer 2021).27 In 2016, the city of Flagstaff eliminated the tipped minimum wage by referendum (Results for America n.d.). Las Cruces, New Mexico, also has enacted a higher tipped minimum wage than the state.28

In some instances, laws setting local minimum wage rates have focused on particular industries. Seattle’s Domestic Workers Ordinance requires domestic workers be paid at least the city’s minimum wage (Seattle OLS 2018a). At least four California cities—Los Angeles, Oakland, Santa Monica, and West Hollywood—have required a higher minimum wage for their hotel workers (LA DPW n.d.; Oakland n.d.; Santa Monica n.d.; West Hollywood n.d.).29

Laws addressing wage theft

Wage theft occurs when employees do not receive wages to which they are legally entitled for their work, including paying workers less than the minimum wage, not paying overtime premiums to workers who work more than 40 hours a week, or asking employees to work “off the clock” before or after their shifts. Cooper and Kroeger (2017) investigated just minimum wage violations, and found that in the 10 most populous states in the country (California, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Michigan, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Texas), 17% of eligible low-wage workers reported being paid less than the minimum wage, amounting to 2.4 million workers losing $8 billion annually. Cooper and Kroeger estimate that workers nationwide lose $15 billion annually from minimum wage violations alone. A 2021 study found that more than $3 billion was recovered on behalf of workers by federal and state enforcers and through private litigation (Mangundayao et al. 2021).

In addition to setting up dedicated enforcement agencies and ensuring that these agencies are robustly funded to pursue violations, local governments can pass laws to address the problem of wage theft. For example, Denver passed a wage theft ordinance that classifies wage theft as a criminal misdemeanor and empowers the city attorney’s office to prosecute claims of $2,000 or less and seek restitution (Denver 2021).

In some instances, such measures may be a way for cities preempted from setting minimum wage rates to nonetheless have an impact on wage-related concerns and to protect workers within their jurisdiction from predation and abuse. Numerous localities in Florida have passed ordinances setting up administrative processes that make it easier for workers to file a complaint and recoup stolen wages without retaining a lawyer. In Florida, Miami-Dade County led the way, followed by Alachua County, Broward County, Hillsborough County, Osceola County, Pinellas County, and the city of St. Petersburg (Huizar 2019b). These ordinances set out a procedure for administrative resolution of wage theft claims by first allowing workers with claims of more than $60 in unpaid wages to settle claims with the city’s help. If those claims are not resolved, workers then may proceed to a hearing where the employer may be exposed to additional penalties (Miami-Dade WTP n.d.). An analysis of the Miami-Dade County Wage Theft Program found that between its adoption in 2010 and September 2014, workers recovered $2,039.83 in unpaid wages, on average, an amount researchers found was “well above the average recovered by federal enforcement” (RISEP-FIU 2014).

Finally, more wage theft protections at the city level may be on the horizon. The Austin (Texas) City Council passed a resolution in early 2022 directing the city manager to develop an ordinance on wage theft, with stakeholder input.30 Houston and El Paso, Texas, had previously passed similar resolutions (Ramirez 2022).

Paid sick and safe leave

Presently, 19 cities and counties have laws requiring employers to permit workers to take time to recover from an illness or care for a sick loved one and to be compensated for that time (A Better Balance n.d.b, 2021).31, 32 Now 14 states and Washington, D.C., also have passed laws requiring paid sick leave (A Better Balance n.d.b), but local governments first led the way. For example, Jersey City, New Jersey, first enacted a paid sick leave ordinance in 2013, followed by 12 additional cities before a statewide law took effect in 2018.33 Research shows that paid sick leave ordinances effectively slow and reduce the spread of contagious illnesses by reducing the likelihood that workers will go to the workplace sick (otherwise referred to as sick presenteeism) (WCEG 2020). Especially for workers in low-wage industries, paid sick leave provides economic security when facing illness. Meanwhile, research has shown that businesses do not find such laws to be particularly burdensome once they are in effect. For example, a study of New York City employers revealed that “[b]y their own account, the vast majority of employers were able to adjust quite easily to the new law, and for most the cost impact was minimal to nonexistent” (Appelbaum and Milkman 2016). Moreover, 86% of the employers surveyed expressed support for the paid sick days law.

Local paid sick leave laws vary—i.e., exemptions for smaller employers, how family and loved ones are defined, the rate at which workers accrue sick time, and when workers start to earn sick time and whether it rolls over. However, many of them were developed with the technical assistance of groups like the nonprofit organization A Better Balance (A Better Balance n.d.a), and therefore have similar features. They generally provide somewhere in the range of 40 to 48 hours of leave annually, and prohibit retaliation against workers for taking leave.

Some of these laws also create a right to “safe leave” for situations in which workers or their family members are victims of domestic violence, stalking, and sexual assault (A Better Balance 2019). Safe leave laws can be used, for example, to obtain a protective order, access social services, or relocate.

Fair scheduling

Eight cities—Chicago; Emeryville, California; New York City; Philadelphia; San Francisco; San Jose, California; SeaTac, Washington; and Seattle—have laws to ensure workers have predictable schedules, more opportunities for existing employees to work, and sufficient periods of rest between shifts (A Better Balance 2022c). This set of policies, which have commonly been referred to as fair workweek or fair scheduling laws, have been championed and implemented because workers, particularly in the service sector, commonly receive their weekly work schedules only a few days in advance, and their scheduled work hours and workdays often change substantially from week to week. Fair workweek laws were first passed at the local level (Fair Workweek Initiative n.d.), paving the way for state-level action; Oregon has now adopted a statewide fair scheduling law.

Research suggests that unstable and unpredictable work scheduling practices undermine workers’ health and well-being and also lead to economic insecurity and income volatility, and that the fair workweek law in Seattle increased not only schedule predictability, but also subjective well-being, sleep quality, and economic security (Harknett, Schneider, and Irwin 2021). Most fair scheduling laws cover specific industries, such as retail or fast-food. They require covered employers to provide an initial estimate of a worker’s schedule upon hiring, advance notice of schedules, and compensation (predictability pay) for employer-initiated schedule changes with less than the requisite notice; workers also typically have the right to decline shifts that do not allow for a requisite period of rest, and the right to request a modified schedule.

In addition, because many workers in the relevant sectors seek additional work hours, fair workweek laws generally require employers to offer additional hours to existing employees before hiring new staff. Such laws also typically include provisions that prohibit employers from retaliating against workers for exercising rights under fair scheduling laws. Fair scheduling laws differ as to which employers are covered (typically limited by size and industry), notice and rest times, the level of predictability pay, and the like. San Francisco’s Family Friendly Workplace Ordinance specifically entitles workers to request a flexible or predictable schedule to assist with caregiving responsibilities, and requires employers to engage in an interactive process with the worker (San Francisco 2013).

Laws governing platform companies in the ‘gig’ economy

Almost all federal and state laws governing the workplace protect employees and not independent contractors. Platform companies in the so-called “gig” economy, in which workers are hired via apps, treat workers as independent contractors instead of as employees, thereby avoiding the obligations of an employer. This practice has led to considerable litigation, including lawsuits by the attorneys general of California and Massachusetts, alleging that such workers are misclassified (Gerstein 2020). Employer misclassification of workers as independent contractors is a longstanding, pervasive problem affecting millions of workers annually (Rhinehart et al. 2021).

New York City and Seattle have both passed ordinances creating various rights and protections for these workers, even as the cities have refrained from determinations about employee status. In 2018, New York City passed legislation34 empowering the relevant regulatory agency, the Taxi and Limousine Commission (TLC), to set minimum pay rates; accordingly, later that year, the TLC issued a rule (NYC TLC 2018) setting a minimum pay standard based on a study it had commissioned (Reich and Parrott 2020). In 2020, Seattle passed a similar ordinance (Seattle OLS 2020i) setting minimum pay for transportation network company drivers. New York City has also passed legislation35 allowing a city agency to set minimum payments for third-party (typically app-based) food delivery and courier providers. A comprehensive proposal to improve pay and transparency about working conditions for such workers was passed in 2022 by the Seattle City Council (Bull 2022, Taylor 2022a).

Seattle also passed a Transportation Network Company (TNC) Driver Deactivation Rights Ordinance (Seattle OLS 2021l), which grants drivers the right to challenge unwarranted deactivations before a neutral arbitrator, and creates a Driver Resolution Center to provide representation for drivers.36

Finally, in 2021, New York City passed a series of policies to protect delivery workers whose precarity was made clear during the COVID-19 pandemic (Figueroa et al. n.d.). An organization of bicycle delivery workers, Los Deliveristas Unidos, played a significant role in advocating for the new law (Los Deliveristas Unidos n.d.; City Staff 2021). The policies include a requirement that restaurants allow delivery workers to use their restrooms as long as they are picking up an order; minimum per-trip payments; transparency for customers and workers about tips (whether the tip goes to workers, in what form, and on what timeline); a prohibition on fees for receiving payment and a requirement that payments are made weekly, including at least one option that does not require a bank account; a prohibition on charging workers for insulated delivery bags; and permission for workers to limit their personal delivery zones (Sugar 2021).

Protections for freelancers or independent contractors

Minneapolis, New York City, and Seattle have passed laws to aid freelancers and independent contractors in securing timely payment for their work. Because such workers are not generally protected by employment law, they often face challenges in securing payment for their work, which is enforced by contract law and therefore typically requires securing legal counsel for any enforcement action (Yang et al. 2020). These local ordinances protecting freelancers require a written contract that includes certain written terms (e.g., pay rate and payment schedule) for a value greater than a minimum amount, require payment within 30 days of completion of the contract, offer protection against retaliation, and set up an administrative enforcement process. In 2022, the New York State legislature passed a state-level Freelance Isn’t Free Act based on New York City’s model (Maher 2022).

Protections against discrimination

Although the focus of this report is labor standards, not discrimination, it is worth noting that local governments have passed laws to expand protections from employment discrimination beyond what is protected under federal and state law. These local laws are typically enforced by local fair employment practices agencies (FEPAs), which are typically separate from agencies that enforce labor laws that regulate workers’ wages, hours, and benefits. For example, at least 330 local governments have passed nondiscrimination ordinances protecting workers from discrimination at work on the basis of sexual orientation, and at least 225 have done so to protect workers from discrimination on the basis of gender identity as well (MAP n.d.; HRC n.d.). Some local ordinances also protect workers from discrimination on the basis of marital or partnership status, family status, immigration status, status as a veteran, credit history, caregiver status, sexual and reproductive health decisions, salary history, weight and height, and status as a victim of domestic violence, stalking, or sex offenses (Vanderbilt 2012; Eidelson 2022; Brown 2002). In addition, federal employment discrimination protections only apply to employers with 15 or more workers, and local ordinances also often cover smaller workplaces (Clampitt n.d.). New York City in 2022 included domestic workers in the law prohibiting workplace discrimination (NYC CHR 2021). In addition, San Francisco in 2017 passed a law requiring employers to provide a reasonable break for a worker desiring to express breast milk for their child and to provide a space for lactation, other than a bathroom, that is shielded from view and intrusion (San Francisco 2017).

Several types of local anti-discrimination laws are described in more detail below.

Fair chance hiring

At least 22 local governments have passed laws requiring private and public employers to consider a candidate’s job qualifications before inquiring about a candidate’s criminal history—commonly referred to as “ban-the-box” or “fair chance” policies (Avery and Lu 2021). They may also prohibit consideration of certain types of past offenses, or require hiring entities to consider evidence of an applicant’s rehabilitation. Even more cities and counties have adopted fair chance hiring for their vendors’ or their own hiring. Fair chance policies vary as to the size of covered employers, when a background check is permitted in the job application and interview process, penalties, and enforcement.

Salary history bans

At least 20 local governments have passed laws prohibiting employers from inquiring about a job applicant’s salary history during the hiring process (HR Dive 2022; AAUW 2022).37 These ordinances seek to remedy systemic pay discrimination against women and people of color by allowing applicants to negotiate a salary based on their qualifications and earning potential, rather than being measured by their previous salary. Some local ordinances apply to private employers operating in the jurisdiction, whereas others apply only to local government hiring processes.

Pay transparency law

In January 2022, New York City became the first city38 to enact a pay transparency law,39 which requires employers to list a minimum and maximum salary for positions located in the city. This type of pay transparency law helps curb pay inequities. The law amends the New York City Human Rights Law (NYCHRL), the city’s ordinance that protects against employment discrimination, and makes any failure to post salary ranges an “unlawful discriminatory practice.” Ithaca, New York also passed a similar pay transparency law in May 2022 that applies to any employer with more than three permanent workers based in Ithaca (Zerez 2022).

Crown Act

Twenty eight municipalities, including New York City, have passed laws prohibiting discrimination based on a worker’s hairstyle or hair texture (NYC CHR 2019). Often known as the Crown Act (NAACP LDEF n.d.), these laws aim to address the impact of natural hair-based discrimination Black workers face in the workplace.

Protections against wrongful termination

Throughout the United States, almost all states have what is known as at-will employment; employers may terminate workers for reasons unrelated to job performance, as long as they are not discriminatory, retaliatory, or otherwise violative of the law. Just cause protections prevent employers from legally firing workers without warning or explanation (Tung, Sonn, and Odessky 2021). Such laws promote economic security and stability for workers and their families; they also protect workers from retaliation for raising concerns about violations of workplace laws.

Both Philadelphia and New York City have adopted ordinances that prohibit employers in certain industries from arbitrarily terminating employees. In Philadelphia, parking workers may only be terminated for just cause (which requires progressive discipline) or a bona fide economic reason (Philadelphia DOL 2021). New York City passed similar legislation applicable to fast-food workers (NYC OM 2021e).40 That legislation was recently upheld in the face of a legal challenge.41

In addition, in the wake of Hurricane Irma in 2017, the Miami-Dade Board of County Commissioners passed an ordinance (Miami-Dade Cty. 2018) prohibiting employers from retaliating or threatening to retaliate against nonessential employees for complying with county evacuation or other county executive orders during a declared state of local emergency.

Worker retention laws

Some localities have passed laws to protect workers’ employment when services are contracted out or when a contract changes hands (see Weil 2014, Weil n.d. on the “fissured workplace”). At least four cities (Hoboken, Newark, New York City, and Philadelphia) have passed laws that generally require successor contractors that operate in those cities to retain employees for at least 90 days, provide written offers of employment, retain employees by seniority, and maintain a preferential hiring list of employees not retained (Keon 2021; Kiefer 2022; Hoboken n.d.b., Jackson Lewis P.C. 2016). These laws differ in the categories of workers that are covered; Philadelphia’s ordinance provides the broadest coverage including security, janitorial, building maintenance, food and beverage, hotel service, and health care services workers (Keon and Sopher 2021). Unlike the policies addressing contractors discussed in Section 8, these ordinances apply to all contractors and subcontractors, not only those contracting with the relevant local government.

Industry-specific protections

Workers in certain industries may be subject to specific harms or be especially vulnerable to violations of the law. As a result, some local governments have passed laws specifically protecting workers in those industries.

Domestic workers

Chicago, Philadelphia, and Seattle have passed laws to provide domestic workers’ rights. In Seattle and Philadelphia, domestic worker bills of rights seek to ensure healthy working hours, sufficient earnings, and protections from sexual harassment and other exploitation. There are 2.2 million domestic workers in the United States—these housekeepers, child care workers, and home care workers are overwhelmingly (91.5%) women and are likely to be people of color, born outside of the United States, and older than other workers (Wolfe et al. 2020). Domestic workers are three times as likely to be living in poverty as other workers, and often are not protected by federal and state labor laws (Wolfe et al. 2020).42 Bill of rights ordinances typically provide domestic workers with meal and rest breaks, paid time off, and protections from sexual harassment and discrimination. Seattle’s law also created a Domestic Workers Standards Board, which provides a forum for employers, domestic workers, worker organizations, and the public to consider, analyze, and make recommendations to the city on other possible legal protections and standards for domestic workers (Seattle OLS 2018a). Chicago and Philadelphia have laws that provide domestic workers with the right to a written contract in English, as well as the language preferred by the worker (Chicago Dept. BACP 2021b; Philadelphia 2021b; Esposito 2021).

Hotel workers

At least seven cities have passed laws requiring hotels to equip workers with panic buttons, GPS-enabled devices that alert security when activated, and other protections (Hotel Tech Report 2022; Oakland OCA 2019). Entering a hotel room occupied by a visitor often places workers at risk of sexual harassment and assault, and data show that women in the hospitality and restaurant industries have the highest rates of sexual harassment on the job (Campbell 2019). In addition to requiring panic buttons, local ordinances typically require notice in each hotel room indicating that workers are equipped with panic buttons, and, in some cases, require hotel employers to develop and comply with a sexual harassment policy, take safeguarding steps after receiving an allegation of harassment, and prohibit retaliation for reporting sexual harassment or assault (UNITE HERE Local 1 2022; West Hollywood CC 2021). At least five cities have also passed laws regulating workloads, including regulation of hours and amount of work denoted in maximum square footage cleaned in a day (Stokes and Sarchet 2018; Santa Monica 2019; Sarchet 2021; Wagner 2020; Seattle OLS 2020f; Emeryville 2022). A few localities require additional payments from employers to increase health care access, and preferential hiring to retain workers when hotel ownership changes (Wagner 2020; Sarchet 2021; Santa Monica 2019).

Fast-food workers

New York City in 2017 passed a law, which is no longer in effect, requiring fast-food employers, upon authorization by an employee, to deduct voluntary contributions from workers’ paychecks and remit them to a nonprofit organization (not a labor union) designated by the employee (NYC n.d.c).43 The voluntary contributions were intended to enable and facilitate such workers having support and assistance from an organization advocating on their behalf, addressing work-related issues and other matters affecting working people.

Grocery workers

Los Angeles, New York City, and San Francisco have grocery worker retention policies that require new grocery store owners to retain employees of the previous owner for a 90-day transitional period after a change in ownership of the grocery store (NYC OLPS n.d.a; PWF n.d.e).44 The ordinances also establish a review process through which workers will be considered for continued employment.

Car wash workers

New York City’s car wash accountability law requires car washes to obtain a license to operate (NYC DCWP n.d.a). In addition to a license application, car washes must provide proof of workers’ compensation insurance, proof of disability benefits insurance, proof of commercial general liability insurance, and proof of unemployment insurance. Notably, car washes must also post a surety bond (also known as a wage bond) to cover potential wage claims as a condition of doing business.

Adult entertainment workers

Minneapolis in 2019 passed an ordinance requiring adult businesses to give workers copies of their contracts, post rules for customer conduct and workers’ rights, and prohibit retaliation against workers who report violations (Otárola 2019). Under the law, managers and owners are also prohibited from taking tips from workers, and workers will be provided security escorts when leaving after a shift. The ordinance also requires businesses to follow standard cleaning procedures, clear tripping hazards, and install security cameras to monitor all areas where entertainers interact with customers.

Wage standards and other requirements for local contractors or license/permit holders

Many localities have placed requirements on their contractors, including prevailing wage laws, living wage laws, and responsible bidder rules. In addition, some localities have created requirements for license or permit holders, in relation to compliance with labor laws or disclosure of past violations. Section 7 contains a detailed discussion of local laws affecting government contractors, and those affecting license and permit applicants and holders.

Higher labor standards for airport workers

Airports throughout the country are owned and operated by public entities—local and state governments, and regional entities composed of such governments (NASEM 2017).45 These public entities have required minimum wages for contractors and vendors at airports as a condition of being permitted to operate there. Many airport workers are low-paid; research has shown declining or stagnant wages, and poor working conditions (Sainato 2018; Editorial Board NYT 2018; Houston n.d.; Dietz, Hall, and Jacobs 2013). The Service Employees International Union (SEIU) has catalyzed airport-driven wage increases as a way to improve the working conditions of poorly paid janitorial, catering, food service, and other workers in airport facilities.

In places where local governments have authority to regulate the airport, many localities have exercised this authority to require all airport contractors to pay a higher minimum wage than the wage broadly required within the surrounding jurisdiction. Counties that have taken such action include Broward County (Fort Lauderdale, Florida) and Miami-Dade County, Florida (Miami-Dade Cty. n.d.a, n.d.b; Broward 2021). Cities taking similar action include Chicago, Denver, Houston, Los Angeles, Oakland, Philadelphia, Portland, Oregon, St. Louis, San Francisco, and San Jose, California (Spielman 2022; SEIU 2019; Houston n.d.; LAWA n.d.; Philadelphia CC 2021b; Holton 2021; Philadelphia CC 2021a; Port of Portland 2020; Port of Oakland 2001, 2021; STL Air Portal n.d.; SF OLSE n.d.d; Aitken 2021). In some instances, additional labor standards are required of airport contractors; for example, San Francisco also applied its health care ordinance to airport workers (San Francisco 2020), and the city of Los Angeles includes a worker retention provision (LAWA n.d.).

Some localities like Miami-Dade County, Philadelphia, and San Francisco, require certain contractors operating at the airport to enter into labor peace agreements with labor unions (LAWA n.d.).46 A labor peace agreement generally requires the employer and union to waive certain rights under federal law with respect to union organizing (for example, neutrality and nonopposition to the union on the employer side and a promise not to strike, picket, or disrupt the employer’s operations on the union side) to ensure uninterrupted workflow or, in the case of government, uninterrupted delivery of public services. In addition, the city of SeaTac, Washington, does not contain Seattle’s airport, but largely surrounds the airport; it passed an ordinance setting minimum employment standards for hospitality and transportation industry employers that requires higher wages for hotels and other businesses in the airport’s immediate vicinity (SeaTac n.d.).

Protecting workers and public health during the COVID-19 pandemic