Tony Avirgan

Guatemalans are being denied access to affordable generic versions of medicines for the treatment of leukemia, glaucoma, and other serious diseases as a result of the Central American-Dominican Republic Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR). According to a study by the Center for Policy Analysis on Trade and Health (CPATH), a provision in the trade agreement favors drug companies by forcing individuals and hospitals to buy far more expensive brand name drugs instead of far cheaper generic versions. The provision in question extends the duration of monopoly protections for medicines beyond that of U.S. patent laws or the World Trade Organization’s multilateral Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPS).[1] The result is that some medicines that are legally available in generic form in the United States are blocked from sale in Guatemala and other countries.

For example, Fludara—used to fight leukemia—will not be available in generic form (Fludarabine phosphate/fludarabina) in Guatemala until September 2016. Another drug, Lumigan—used to treat glaucoma—will not be available in generic form (Bimaprost) until October 2016.

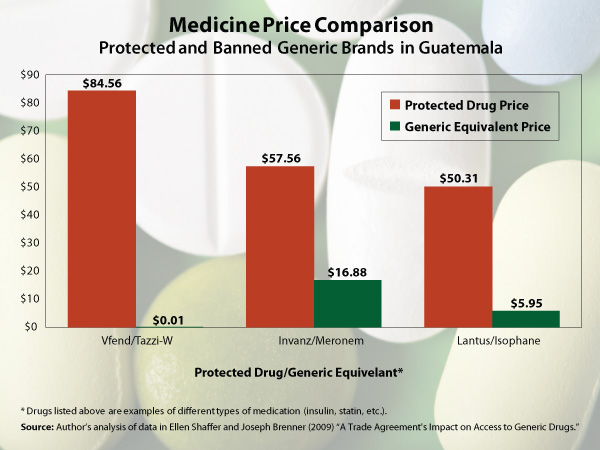

The price difference between branded medicines and generics is enormous (see chart below).

The same rules apply to generic medicines in other CAFTA-DR countries: Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua. The U.S. Congress, while considering the Peru Free Trade Agreement in May 2007, removed these patent extension provisions as well as changed rules that restricted access to clinical trial data on generic medicines, specifically citing the potential negative consequences for lower-income countries.

The United States Trade Representative and the Department of Commerce should immediately apply this same principle to all CAFTA-DR countries.

[1] 21 US Code 3/55(c) (E) (ii) limits patent protection in the United States to five years or less. TRIPS 39.3 allows monopoly protection only to protect against unfair commercial use and to protect new chemical entities. I CAFTA 15.10 gives applicants (for example, pharmaceutical companies) the right to five years or more of monopoly protection at the discretion of the applicant. (Footnote 15 in CAFTA Article 15 preserves the right of the United States to maintain a shorter term of monopoly protection, but does not offer this to any other signatory country that did not already have a shorter term codified in law.)