See Snapshots Archive.

This week’s Snapshot previews data to be presented as part of the forthcoming The State of Working America 2006/07.

Snapshot for July 19, 2006.

U.S. government does relatively little to

lessen child poverty rates

By Sylvia A. Allegretto with research assistance from Rob Gray

Government policies, such as tax policy and transfers, have the potential to greatly reduce high child poverty rates that would otherwise prevail if left solely to the market incomes families receive from work and other sources. The anti-poverty effectiveness of such policies varies considerably across countries. Compared to other industrialized nations, the United States is woefully lagging: even after government intervention over one-fifth of all U.S. children were living in poverty in 2000.

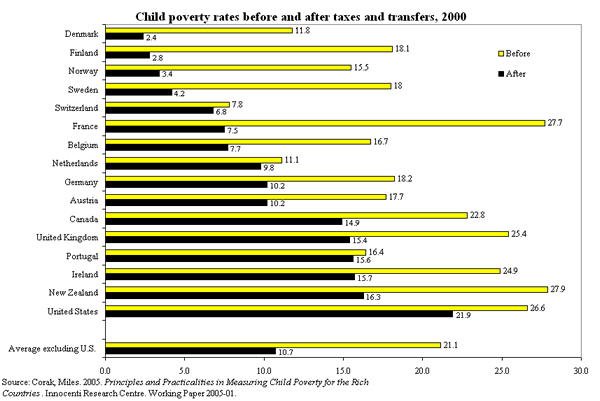

The Figure below shows child poverty rates both before and after government intervention for 16 developed countries. Excluding the United States, the average rate of child poverty without governmental assistance was 21.1%. That is, the distribution of income based solely on market outcomes left about a fifth of children in poverty.1 Before taxes and transfers, the United States had one of the highest market-based rates of child poverty in 2000: 26.6%. Four other countries—New Zealand, France, the United Kingdom, and Ireland—had comparably high market rates of child poverty.

The figure also shows that U.S. policies were relatively ineffective in supplementing poverty-level incomes to keep children out of poverty. After taking into account the taxes (including refundable taxes) and transfers, the U.S. still led the 16 developed countries in child poverty. On average, government taxes and transfers in the other 15 countries reduced child poverty significantly—by about half—dropping 10.4 percentage points to 10.7%. France had the largest redistributive decline of 20.2 percentage points to a child poverty rate of 7.5%. By contrast, the U.S. rate was reduced by just 4.7 percentage points to 21.9%—by far the highest child poverty rate of all 16 developed countries, even after government assistance.

The contrast between the great wealth in the United States and such appallingly high child poverty rates is quite stark. The United States needs to make a strong commitment to reduce child poverty.

[1] Poverty is defined as families with incomes below one-half the median income for that country, which is a traditional poverty measure for international comparisons.