Today, the co-chairs of the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform presented a revised version of their plan, but also announced that a final vote would be delayed until later this week.

With the delay, it is becoming increasingly clear that the Bowles-Simpson plan will not receive the required 14 votes to send the report to the President and Congress. The rejection of the proposal should not be seen as a failure to take deficit reduction seriously, but rather that the policy approach adopted by the co-chairs is flawed.

Most fundamentally, the report fails to fully acknowledge the current economic crisis. The report states that the reductions in annual appropriations would require “serious belt-tightening” beginning in just 10 months, despite the fact that the unemployment rate is expected to remain between 9% and 10% at that point. Despite paying lip-service to a payroll tax holiday, the plan includes no concrete, immediate action to create jobs or to spur economic growth in the near term.

We sometimes hear that having a long-term plan for attaining fiscal balance opens up the possibility for a rigorous near-term intervention to create jobs, which requires deficit spending. In this plan we get extensive long-term pain for no short-term gain.

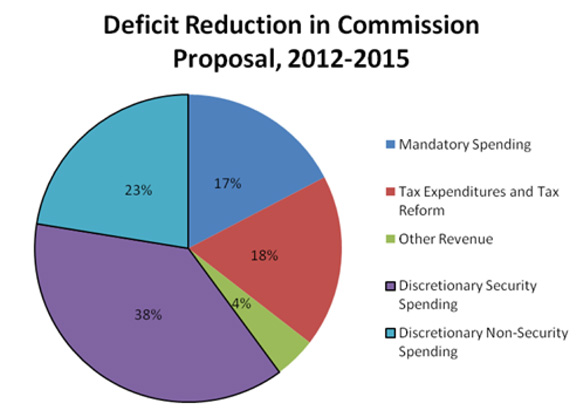

The Bowles-Simpson plan also continues to misdiagnose the problem by focusing on cutbacks in domestic investments and Social Security—neither of which is a prime driver of the deficit in the short- or long-run. Nearly one-quarter of the near-term reductions (2012-15) in the report come from blunt-force cutbacks to domestic investments; however, the report is short on specific recommendations about how to accomplish this. Instead the proposal primarily recommends budget process changes, agency reviews, and even the creation of yet another committee to identify savings. Rather than taking on the hard choices, the Bowles-Simpson plan kicks the deficit-reduction can down the road. But the plan’s failure to explicitly reject a continuation of the Bush tax cuts for the wealthiest Americans—a giveaway that will add $700 billion to the deficit—is perhaps the clearest example of ducking hard choices.

Although the overall direction remains flawed, this proposal does have some positive elements. In particular, its recommendation to reduce spending by the Department of Defense, its attempts to build on cost-savings measures included in the Affordable Care Act, and some of its illustrative tax policies, such as its treatment of capital gains and dividends as ordinary income. However, it falls short of a comprehensive proposal in two critical ways: its inadequate approach to revenue collection and its counter-productive approach to job creation and economic growth.