Unemployment has remained at 9.5% or above for the past year and is likely to remain elevated or inch even higher through the end of 2011. The reason for this prolonged jobs crisis is fairly simple: The bursting of the housing and stock bubbles and the financial crisis lead to a severe cutback in household consumption and business investment. The policy conclusion drawn from this narrative is that we need faster growth to increase the demand for workers and reduce unemployment.

But many are promoting a different, misguided narrative, that a large share of unemployment is “structural,” meaning that there is a mismatch between unemployed workers and the jobs becoming available. Structural unemployment would result from workers having inadequate skills, or not living in the places where there are jobs. Some have postulated that employers have substantially revamped their production processes in this downturn, thereby eliminating the need for many of the types of workers who are currently unemployed. Still others suggest that the housing bubble lead to a bloated construction sector and many of those jobs will never come back, leaving many construction workers needing to seek employment in different professions for which they may not be qualified.

But many are promoting a different, misguided narrative, that a large share of unemployment is “structural,” meaning that there is a mismatch between unemployed workers and the jobs becoming available. Structural unemployment would result from workers having inadequate skills, or not living in the places where there are jobs. Some have postulated that employers have substantially revamped their production processes in this downturn, thereby eliminating the need for many of the types of workers who are currently unemployed. Still others suggest that the housing bubble lead to a bloated construction sector and many of those jobs will never come back, leaving many construction workers needing to seek employment in different professions for which they may not be qualified.

Why does the cause of our high unemployment rate matter? Because it will dictate the policy prescription. The policy implications of structural unemployment would be that (1) it would be foolhardy to pursue policies that increase the demand side of the equation (fiscal stimulus, either tax cuts or increased spending, or monetary policy) to lower unemployment; and (2) the appropriate policy is to offer education and training to the unemployed to help them make a transition to new occupations and sectors.

EPI’s new paper, Reasons for Skepticism About Structural Unemployment, shows that there has been little evidence to support the claim of extensive structural unemployment and that the pattern of employer behavior regarding job openings, layoffs and hires does not support such a claim.

This matters quite a bit for guiding policy. Note the recent statement of the Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank president, Narayana Kocherlakota:

“What does this change in the relationship between job openings and unemployment connote? In a word, mismatch. Firms have jobs, but can’t find appropriate workers. The workers want to work, but can’t find appropriate jobs. There are many possible sources of mismatch—geography, skills, demography—and they are probably all at work. Whatever the source, though, it is hard to see how the Fed can do much to cure this problem. Monetary stimulus has provided conditions so that manufacturing plants want to hire new workers. But the Fed does not have a means to transform construction workers into manufacturing workers.

Of course, the key question is: How much of the current unemployment rate is really due to mismatch, as opposed to conditions that the Fed can readily ameliorate? The answer seems to be a lot…… Most of the existing unemployment represents mismatch that is not readily amenable to monetary policy.”

A better explanation for high unemployment is that there are simply not enough jobs to go around. The economy is operating far below its potential output because of a shortfall in demand caused by an extreme loss of financial and housing wealth, and the reduced consumption that resulted.

Consider the evidence. Manufacturing capacity fell to 71.6% in June 2010 from 79.1% in December 2007. Vacancies in commercial offices now stand at 17.4%. Total demand in the second quarter of 2010 is still below its pre-recession level. In fact, total output, as measured by gross domestic product, was still 1.3% below its pre-recession level in the second quarter of this year. The Congressional Budget Office conservatively puts the “output gap,” the difference between potential and actual output, at 6.4% in the second quarter. I would say the gap is more like 9%.

In my view, the pervasiveness of (1) lost employment and output across most industries and, (2) high unemployment across types of workers by state, education, age, and occupation, suggest an aggregate or macroeconomic explanation rather than one rooted in a few sectors or locations or a lack of workers’ skills.

The claim of extensive structural unemployment presumes that millions of workers are now inadequately prepared for available jobs even though they were fruitfully employed just a few months or years ago. Let’s look at that line of thinking from a few different angles:

Productivity, Technology Investment: Productivity did grow a pretty spectacular 6.3% from early 2009 to early 2010, but that was the extent of productivity growth since the recession started in late 2007. Net investment in business equipment and software in 2009 (the latest data) was actually negative, for the first time since World War II. This alleged structural transformation of production processes that left four to five percent of the labor force inadequate for the available jobs was clearly not associated with new equipment or new technological processes.

Location: If all of the country’s unemployed workers were to relocate to states with low unemployment, there would still not be enough jobs to go around. There are only 11 states — with a total adult population of about 17 million — where the unemployment rate in June was less than 7.0%. If all the unemployed moved to those states they would nearly double the labor force there.

Construction: It is true that construction has suffered in this downturn, losing nearly two million jobs, or 25% of all private-sector jobs lost. But this is not what is fueling the unemployment problem. Figure A shows that in the second quarter of 2010, unemployed construction workers comprised 12.4% of the unemployed and 12.5% of the long-term unemployed: They are no more likely to be long-term unemployed than those displaced from other sectors. Even before the recession, in 2007, unemployed construction workers were 10.6% of all unemployed and 11.0% of the long-term unemployed.

Beveridge Curve: The Beveridge Curve describes the historical relationship between unemployment and job openings and helps predict how high or low the unemployment rate should be, given a certain number of job openings. There has been much attention to the mid-July blog post by Dave Altig, research director at the Atlanta Federal Reserve Bank, who used such an analysis to suggest that almost a third of the unemployed, or 4.6 million workers are structurally unemployed. Less noticed is that Altig retreated from this claim just a month later.

His original claim was based solely on a simple analysis of job openings and unemployment since 2000, encompassing the experiences of just two recessions. But one month later, when Cleveland Federal Reserve economists Murat Tasci and John Lindner conducted a more comprehensive analysis of data back to 1951, they showed that unemployment being higher than what the Beveridge Curve would suggest is not “anomalous.” Rather it happened in the initial recoveries following the deep recessions in the 1970s and 1980s as well.

Lookin

g for Evidence

In fact, one of the curious aspects of this misguided theory of structural unemployment is how hard it is to find any research tying this story to actual detailed trends in employment, unemployment or output data. Our paper also shows:

–There have been between five and six unemployed workers for every job opening since mid-2009, clearly suggesting a shortage of jobs. This job seeker ratio is roughly double what it was in the last recession.

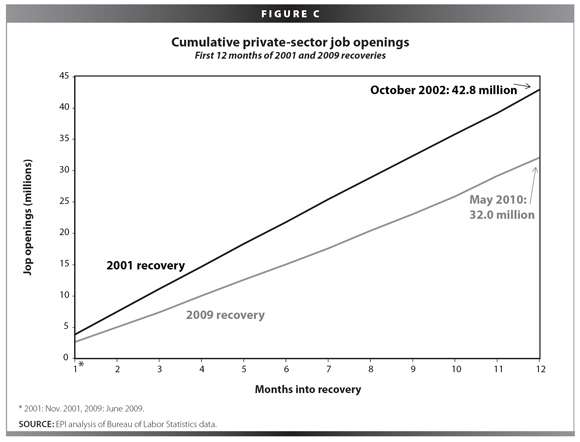

–In the first 12 months of this recovery there were 32.0 million job openings, 10.0 million fewer than the first twelve months of the prior recovery, one known for being a jobless recovery.

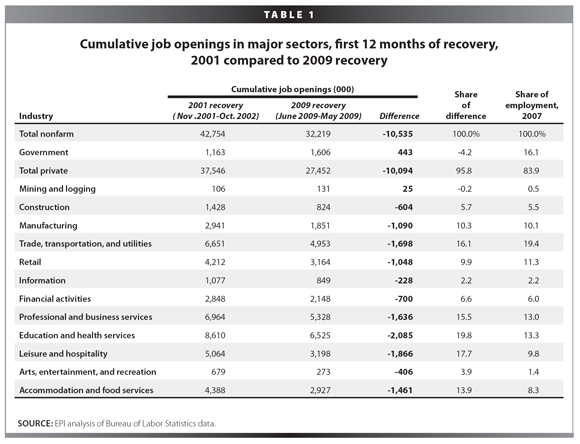

–The shortfall of job openings in this recovery is pervasive, and spans nearly every sector including labor intensive service industries such as hospitality, entertainment and accommodation. Construction is responsible for just 6% of the overall shortfall in openings.

–Layoffs during the early stages of this recovery are comparable to those in the prior recovery, and cannot alone explain high unemployment.

–Hiring exceeds openings in the private sector more so now than earlier in this recession and more so than in the early 2000s recession. This evidence runs contrary to notions that employers are having more difficulty now filling jobs.

It is time to stop thinking about unemployment and the failure to generate job openings as being driven by developments in particular sectors since the trends are pervasive across all sectors. Figure C, also from the Briefing Paper, shows the ratio in each sector of the cumulative job openings in the current “recovery” to those in the early 2000s recovery.

This measure shows how far short this recovery’s job openings are to those of the earlier recovery for each sector. It is clear that the shortfall in job openings is pervasive, occurring in every sector (except mining). Recent openings averaged 72% of those in the earlier recovery. Sure, recent construction job openings were just 58% of those in the earlier recovery. However, the shortfall in job openings was also very severe in labor intensive service industries such as hospitality, entertainment and accommodation.

Table 1, from our Briefing Paper, shows the job opening data for each sector in both the 2001 and 2007 recoveries, to allow an assessment of the scale of the recent openings shortfall by sector. Construction is responsible for 5.7% of the recent shortfall in openings but that is comparable to that sector’s 5.5% share of employment, meaning construction has not played any outsized role in the failure for openings to rise as fast now as in the earlier recovery. The shortfall has predominately been driven by private service sector industries (professional and business services, health, education, entertainment, hospitality, and accommodations) which generated 71% of the openings shortfall though had just 46% of total employment. In fact, the worst performing industry under this measure was “Leisure and Hospitality,” which accounts for 10% of employment but 18% of the job openings shortfall.

Our findings also fail to support the theory that more structural changes within industries are leading to more layoffs and impeding a growth in overall employment. A look at the cumulative layoffs in this recovery compared to the last recovery, as in Figure D from our report, shows that layoffs are not a piece that fills in any puzzle: the cumulative layoffs in each recovery are totally comparable.

Finally, in Figure E, we examine whether it is harder to fill job openings, which would suggest structural challenges such as having workers with the right skills or in the right locations. The data for the private sector, however, show it is easier to hire people now than in the recovery following the last recession, or earlier in this recession, at least as reflected in the ratio of hires per job opening.

Presumably, if employers were having trouble finding adequately skilled workers, it would be taking them longer to fill vacancies and the ratio of hires to openings should fall. In fact, the opposite has occurred: the ratio of hires to job openings has been somewhat higher in this recovery (averaging 1.7 hires per job opening) relative to the earlier recovery (averaging 1.5 hires per job opening). Moreover, this ratio has increased since the recession started. There is no indication of a growing structural problem. Remember, too, how these data are timed. “Job openings” is the count of available jobs on the last day of the month. “Hires,” on the other hand, is the sum of all hires completed throughout the month. As long as the number of hires is larger than the number of openings, it means that it is taking less than a month to fill those jobs.

Widespread claims that our unemployment crisis is structural are not only inaccurate, but they imply that macroeconomic tools such as fiscal policy (spending or tax cuts) or monetary policy can not address our unemployment crisis. Surprisingly, perhaps amazingly, there’s no systematic empirical evidence for such assertions. Policy makers should understand that the problem faced by the unemployed is a simple scarcity of jobs, a feature of the labor market facing every group of workers regardless of education, sector, occupation or location.