Jobs Picture, December 5, 2008

Job losses accelerate at alarming rate in November

by Jared Bernstein and Heidi Shierholz with Tobin Marcus

The American labor market is losing jobs at a truly alarming rate. Payrolls contracted by over half a million jobs last month and unemployment rose to 6.7%, according to today’s report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The under-employment rate–the broadest measure of weakness in the job market–soared to 12.5%.

The loss of 533,000 jobs is the largest monthly payroll loss since the 1970s, and the worst month for payrolls thus far in the recession, which began in December 2007. Moreover, downward revisions of job losses for the past two months subtracted another 200,000 from payrolls. In total, jobs are down by 1.9 million since the recession began.

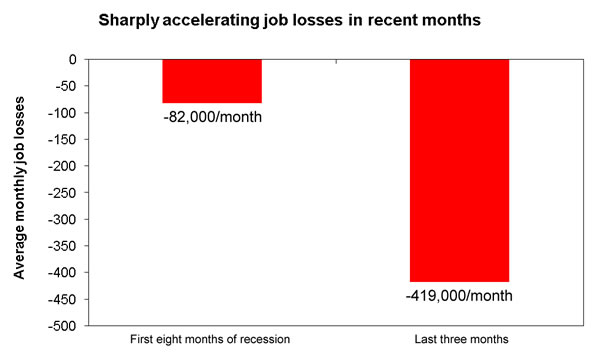

In recent months, as the economy has significantly worsened, the pace of job losses has accelerated. From January through August, the average monthly rate of job loss was 82,000, but for the past three months (September-November), the average monthly loss has been 419,000 (see figure below).

The unemployment rate rose from 6.5% in October to 6.7% in November, its highest rate since October 1993, and two points above its year-ago level. There are now 10.3 million unemployed people in the United States, an increase of over three million in the past year. The increase in the jobless rate is notable because the labor force unexpectedly contracted last month by over 400,000. Since the unemployment rate includes only those workers officially counted as part of the labor force, a contraction in the labor force would normally keep the unemployment rate from rising. But because almost 700,000 jobs were lost in the BLS Household Survey (from which unemployment is drawn), the jobless rate increased.

Under-employment, a more comprehensive measure of the extent of weakness in the job market, rose to 12.5%, its highest level on record since the current series began in 1994, and more than four percentage points above its year-ago level. The growth in this more comprehensive measure of slack was largely driven by an increase in people who work part time but want a full-time job–up 621,000 from October, and by 2.8 million over the past year. All told, there are now an estimated 19.6 million unemployed or under-employed workers in this country, amounting to about one in every eight people in the labor market.

The decline in employment rates is another clear sign of recession. Economists view this measure–the share of the population employed–as a proxy for labor demand. The overall employment rate fell to 61.4% last months, 1.6 points below its year-ago level. Labor demand by this indicator has contracted especially sharply for men. Their rate was down to 67.5% last months, 2.2 points below its level one year ago, and the lowest level in the 60-year history of this data series (for African American men, the rate is down by over three points).

The number of industries creating jobs at this point is alarmingly low, an indicator of the pervasive scope of the weakness in the job market. Most industries–over 70%, according to the diffusion index–contracted last month. The auto industry, which has been the focus of many in Congress in the last few weeks, continues to struggle. Motor vehicle and parts manufacturers lost 13,100 jobs, while employment in vehicle and parts dealers declined by 27,000. Two other key industries–retail trade and professional services (office jobs, temps, legal services)–posted large losses, with retail down 91,000 last month and professional services down 136,000, including a loss of 78,000 temp workers.

Retail is, of course, a key sector this time of year and is an informative bellwether of how the problems in the economy are feeding into the labor market. The 91,000 loss in today’s report reflects a negative seasonal adjustment, because retailers always bulk up on hires this time of year. On a non-seasonal basis, retail jobs were up 217,000. To put this value in context, note that comparable numbers for the past three Novembers have been around 400,000.

Hourly earnings accelerated last month, up 3.7% over the past year. Given the reduction in the rate of inflation, real hourly earnings will likely be positive over the past year. However, the loss in hours worked is pushing in the opposite direction on paychecks, resulting in weekly earnings being up only 2.8% over the past year. Thus, paychecks are likely to remain squeezed, as loss of hours offsets real hourly earnings gains.

Given the dramatic contraction in job growth, large numbers of job seekers are stuck for months at a time in unemployment. Extended unemployment spells, as measured by the share of the unemployed who have been jobless for at least six months, decreased slightly in November to 21.4%.It is still the case, however, that over one-in-five unemployed workers has been jobless for over half a year.

Digging beneath the surface of the overall unemployment rate reveals large differences in unemployment among racial and ethnic subgroups. The unemployment rate for blacks increased to 11.2% in November, an increase of 2.8 percentage points over the last year, while white unemployment rose to 6.1%, an increase of 1.9 percentage points over the last year. The unemployment rate for Hispanics dropped insignificantly to 8.6% in November, but has increased over the last year more than for other subgroups (2.9 percentage points). The bust in residential housing likely explains this annual increase, as many Hispanic workers lost jobs in construction (the unemployment rate in construction was over 12% last month).

As this recession deepens, the employment picture for these subgroups will only worsen. Economic forecasters are projecting an unemployment rate of at least 9% by the end of 2009. Historically, when the overall unemployment rate has been around 9%, the unemployment rate has been around 8% for whites, 17% for blacks, and 12.5% for Hispanics.

What explains the sharply deteriorating job market captured in today’s report? A large part of the explanation lies with two negative forces: consumer retrenchment and the credit crunch. Demand for labor is ultimately driven by consumer’s demands for the goods and services employers provide. But the stalwart American consumer is under great stress, and after decades of consistent spending is finally pulling back, thus leading to diminished consumer demand and sharp job losses.

Credit remains the lifeblood of American businesses, large and small. Given the financial meltdown, the difficulty businesses currently face accessing credit is curbing their abilities to finance new endeavors, or, in the short run, to finance healthy day-to-day operations.

Together, these two forces–consumer retrenchment and the credit crunch–help explain the sharp acceleration in job losses in recent months. Policy makers must recognize this deterioration and craft their responses accordingly. Our job market is now shedding jobs at a truly alarming rate, a rate measurably worse than past recessions. We face an emergency that certainly equals those in the financial markets in recent months. The American workforce is too big to fail.