EPI’s Daniel Costa appeared as a witness and submitted the following written testimony before the U.S. House Subcommittee on Health, Employment, Labor and Pensions, on Wednesday, September 13, 2023 at 10:15 AM, for hearing titled “The Impact of Biden’s Open Border on the American Workforce.”

Introduction

Thank you to Chair Good, the Committee Chair as well as Ranking Member DeSaulnier, and other distinguished members of the Subcommittee for allowing me to testify at this hearing on the current challenges of border management and the connection to workforce issues. I am a lawyer and researcher and director of the immigration program at the Economic Policy Institute, a nonprofit, nonpartisan think tank dedicated to advancing policies that ensure a more broadly shared prosperity, and that conducts research and analysis on the economic status of working America and proposes policies that protect and improve the economic conditions of low- and middle-income workers—regardless of their immigration status—and assesses policies with respect to how well they further those goals. I am also a Visiting Scholar at the Global Migration Center at the University of California, Davis.

The purpose of this hearing is to discuss and explore the possible impacts on the American workforce that new arrivals at the Southern U.S. border may be having. While it is always important to assess how current realities and policies impact workers and labor standards, it must be noted at the outset that there is scant evidence that recent arrivals to the Southern U.S. border—the vast majority of whom are turning themselves into border officials and requesting that they be assessed for eligibility for the available forms of humanitarian relief that are established in U.S. law, such as asylum—are having a detrimental impact on U.S. workers, wages, or employment.

The problems facing the American workforce are not what happens at the border, but at the workplace. Threats to labor standards come from rampant lawbreaking by employers who operate with near impunity, and this committee has the authority and jurisdiction to move legislation that could make significant impacts in the lives of working people, regardless of race, gender, or immigration status. To improve conditions and lift standards in workplaces across the country, our laws and enforcement apparatus must protect all workers and hold lawbreaking employers accountable.

With that in mind, despite the fact that this Subcommittee does not have jurisdiction over border management and enforcement, I would like to briefly address the situation at the U.S. border before turning to the workforce issues that Chairman Good has expressed concern about.

The main challenges at the Southern U.S. border are adequate staff and resources for processing and capacity, as well as a lack of funding for adjudication

Despite the obvious global realities driving displacement, many critics of immigration are framing the situation at the U.S. border as one of lawlessness, open borders, and chaos, but the reality is that the challenges faced by the Biden administration are mainly ones of staff capacity and resources.

First, it is worth reiterating that the vast majority of persons arriving at the U.S. border are seeking out and turning themselves into law-enforcement officers and requesting humanitarian protections under U.S. law, as they are permitted to do. While some may be attempting to enter the United States without inspection, the vast majority are in fact complying with U.S. law, by requesting asylum or by attempting to schedule an appointment through the CBP One application—both of which are, by definition, a legal process. The CBP One application has had technical problems and is the subject of valid criticisms, a subject that has been reported on widely.1 But nevertheless, persons who utilized either route and are now present in the United States while going through the asylum adjudication or parole processes are not present in the United States unlawfully—in other words they are not “illegal immigrants” as some of the other witnesses for this hearing have often referred to them as.

The White House recently sent a request to Congress for a supplemental appropriations package which includes a request for roughly $4 billion to fund their efforts at border enforcement and management, shelter and support services, and adjudication of claims.2 While some immigrants’ rights advocates have levied valid criticisms about how the funding would be utilized,3 especially with respect to enforcement, the request itself is nevertheless evidence of a significant shortfall in resources to process and adjudicate persons who are encountered at the U.S. border.

And as some advocates have pointed out previously, Congress has appropriated funds for immigration enforcement at a rate that is eight times more than what it has appropriated for adjudications at immigration courts and for asylum and refugee operations at United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS): $36.9 billion for Border Patrol and ICE’s Enforcement and Removal Operations vs. $3.5 billion for the immigration court systems and USCIS’s Refugee, Asylum, and International Operations Directorate.4 This lack of investment in adjudication resources has been one of the primary drivers of backlogs and delays in the immigration system. These processing delays are also further enabling exploitation in the workplace, including a resurgence of illegal child labor.

It is clear that more resources are needed, at least for adjudication and shelter and support services, and that the main challenge at the border is processing new arrivals in a fair and humane manner and adjudicating their claims in a timely fashion. It’s also worth noting, that as Congress is currently going through the appropriations process for the next fiscal year, that either a government shutdown or federal budget cuts would only harm the needed services, staffing, and capacity required to address these challenges.

There’s little to no evidence that new arrivals at the U.S. border are negatively impacting the economy

Is it true, as Chairman Good has said, that “[t]he American workforce has not escaped the devastating impact” of what the Chairman refers to as “the worst illegal immigration catastrophe in American history”?5 And if so, what is the evidence for it?

First, it should be noted, as I touched upon in the previous section, that the current challenge at the border is not one of “illegal” immigration, but primarily a challenge of processing and adjudicating arriving migrants who wish to avail themselves of humanitarian protections under U.S. law. And then secondly, we must address the question of if and whether the recent arrivals at the U.S. border have impacted the U.S. economy, if at all. To address this, the following subsections discuss the importance of immigrant workers in the U.S. economy, and the current state of the U.S. labor market.

Immigrant workers play an important role in nearly all sectors of the economy

Numerous scholars, institutions, and government agencies have documented the key role that immigrant and temporary migrant workers play in the U.S. economy. Without immigrant workers, many sectors of the economy would cease to function adequately—whether it be the construction of buildings, crop production, or information technology services. This section discusses and cites some of those sources.

The latest report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) on the labor force characteristics of foreign-born workers shows that in 2022, immigrant workers accounted for 18.1% of the U.S. civilian labor force, an increase of 0.7 percentage points compared to 2021.6 According to the U.S. Census, the share of the U.S. population that is foreign-born was 13.6% in 2021; if this share held in 2022, it means that immigrants are more likely to work or actively seek work than U.S.-born (referred to by BLS as “native-born”) workers, hence explaining their higher share of the workforce relative to population in the labor force by 4.5 percentage points. The labor force participation rate of immigrants was 65.9%, which was 4.4 percentage points higher than the labor force participation rate of the native-born.7

According to BLS, immigrant workers were also “more likely than native-born workers to be employed in service occupations (21.6% versus 14.8%); natural resources, construction, and maintenance occupations (13.9% versus 7.9%); and production, transportation, and material moving occupations (15.2% versus 12.1%).”8 Others have made similar findings. For example, the Migration Policy Institute (MPI) reported that immigrants accounted for 17% of the workforce between 2017 and 2021 and represented 21% of all workers in the food industry, excluding restaurants. They also reported that immigrants were 18% of transportation workers, 22% of grocery and farm product wholesalers, 35% of meat processing workers, 25% of seafood processing workers, and 16% of grocery retail workers.9

The Immigration Research Initiative also recently reported on the immigrant workforce. “Immigrants are a big and important part of the economy,” the report stresses, with immigrant labor responsible for 17 percent of total GDP in the United States.”10 Contrary to common misperception, the report shows, immigrants work in jobs across the economic spectrum, and in a wide range of occupations. The report underscores two basic realities. On the one hand, the majority of immigrants are in middle- or upper-wage jobs—with 48% employed in middle-wage jobs, earning more than 2/3 of median earnings for full-time workers (or $35,000 per year), and 17% are in upper-wage jobs, earning more than double the median. On the other hand, immigrants are “at the same time disproportionately likely to be in low-wage jobs. In all, 35 percent of immigrants are in jobs paying under $35,000, compared to 26 percent of U.S.-born workers.”11

These data show that immigrant workers are playing a vital role all across the U.S. economy. This is virtually an undisputable claim.

Major economic indicators show a strong and growing economy

While policymakers and some of the witnesses for this hearing may argue that immigrants and recent arrivals to the U.S. border are negatively impacting the economy and American workers, they will be hard pressed to point to economic indicators that would support their claims. In fact, the major economic indicators reveal that the U.S. economy is doing well, growing, and that workers are seeing wage gains. This is due in large part to the appropriate scale of fiscal policy relief passed by Congress and the administration over the last 2 to 3 years to spur a strong recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the 3.8% unemployment rate for August 2023 means that the nation’s unemployment rate has been below 4.0% since January 2022 – the longest stretch of sub-4% unemployment since the 1960s.12 Job openings hit record highs in 2022, and remain substantially above pre-pandemic records.13 The labor force participation rate of prime-age workers (those between the ages of 25 and 54) hit its highest level in decades this summer.14 Strong nominal wage growth has started delivering reliable gains in inflation-adjusted wages for most workers in recent months as the inflationary shock of 2022 subsides.15 In short, nothing in labor market data in recent years would indicate that the U.S. has too many workers relative to jobs. This is, in fact, the most favorable balance between labor demand and supply we’ve seen in decades. These economic gains were largely achieved through policy choices that prioritized rapid recovery and investments to make us more resilient in the future.

Other indicators show that this strong economy has reached traditionally disadvantaged groups. Wage growth in 2022 was by far fastest among the lowest-wage workers. The prime-age labor force participation rate and employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) of Black workers has hit record highs in the past year, and the unemployment rate of Black workers has hit record lows. (However, the EPOP of Black workers is still lower than white workers when adjusting for age. But if we are able to continue a trend of sustaining a tight labor market and making positive policy choices, we could continue to see progress on narrowing the gap.)16

The economy is of course, not perfect. Many workers are struggling with the high cost of goods and services inflicted by the global inflationary shocks of pandemic re-opening and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Even before this inflation shock, the cost of necessities like housing, education, child care, and health care have been extremely burdensome for moderate-income families. The repeal of pandemic-era safety net expansions that materially improved these families’ lives has been deeply damaging – this week’s Census data on income and poverty will likely show a near doubling of child poverty in 2022, driven in large part by the expiration of pandemic programs.17 If Members of Congress truly care about workers and wish to help them, they should focus their efforts on making improvements in the lives of American workers by investing in both human and physical infrastructure and improving labor standards rules and enforcement—for instance by raising the federal minimum wage and adequately funding the Wage and Hour Division in the U.S. Department of Labor—as well as the National Labor Relations Board, to protect workers and unions against the illegal tactics that employers use to discourage organizing drives and union elections. Demonizing immigrants and persons fleeing persecution, conflict, and disasters, and blaming them for the U.S. economy not being even better—without any evidence—is a distraction that will not improve the lives of workers.

There is an ongoing displacement crisis around the globe, including in the Western Hemisphere, which is driving new arrivals at the border

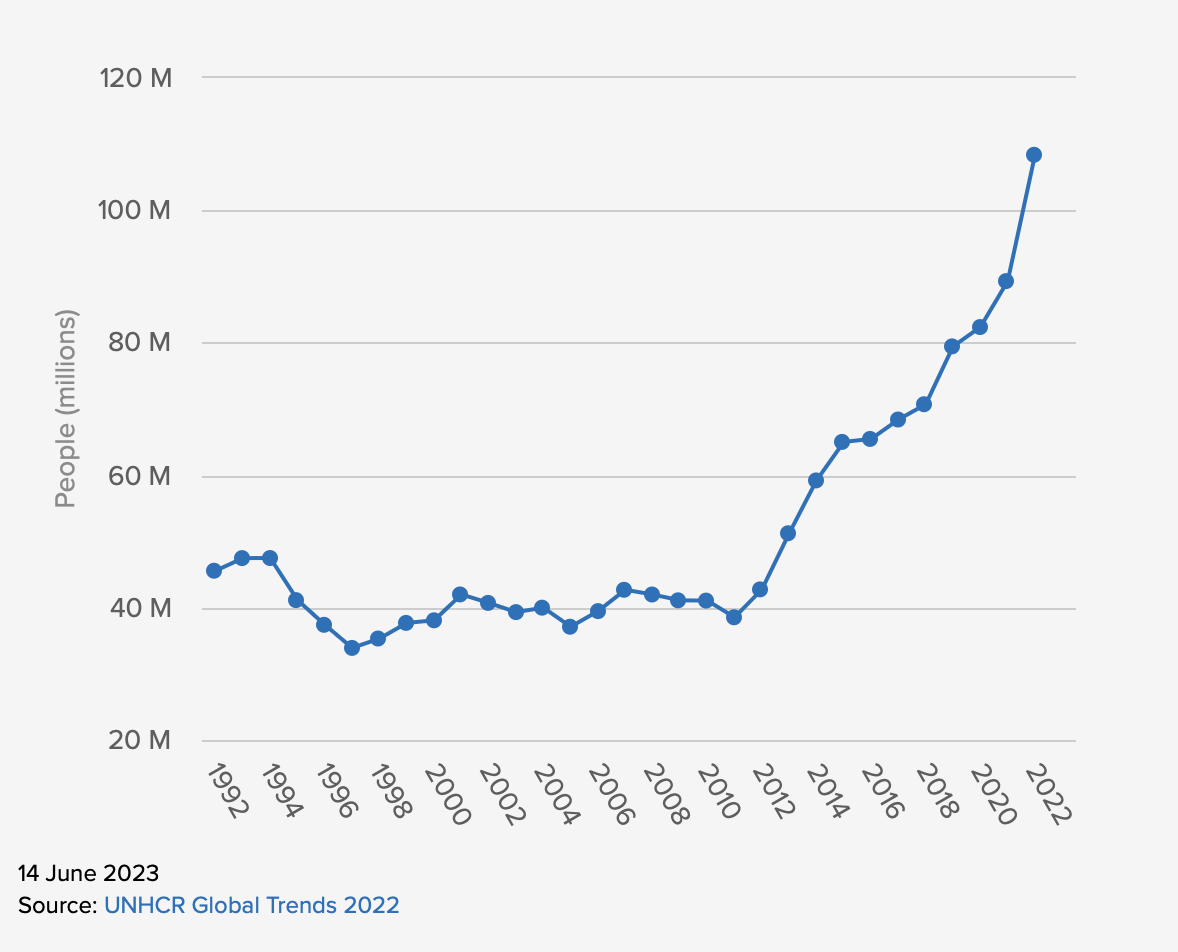

Although displacement and border management does not fall under the purview of this Subcommittee or the full Committee, one important point about the broader context for the number of arrivals at the U.S. border should be acknowledged: There is an ongoing displacement crisis worldwide, with the numbers of people who have been forcibly displaced increasing sharply over the past decade. As shown in Figure A, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reported in June that 108.4 million people were forcibly displaced across the globe, “as a result of persecution, conflict, violence, human rights violations or events seriously disturbing public order.”18 This is the highest number on record, more than two and a half times the number a decade ago, including an increase of 19 million persons displaced in just one year, from 2021 to 2022. A multitude of humanitarian crises, political instability, conflicts, and disasters are driving this around the world.

108.4 million people worldwide were forcibly displaced: At the end of 2022 as a result of persecution, conflict, violence, human rights violations or events seriously disturbing public order

Source: Figure reproduced from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Figures at a Glance, June 14, 2023, from UNHCR Global Trends 2022.

The Western Hemisphere has not been spared, with multiple displacement crises taking place in the region, which have been the primary drivers of persons arriving at the U.S. border. For example, Colombia is now hosting over 2 million Venezuelan migrants who are in need of international protection and has provided many of them with legal status and a ten-year right to remain.19 Costa Rica, a country with just 5.2 million inhabitants, is hosting 271,000 forcibly displaced migrants,20 which represents roughly just over 5% of its total population. The United States, the richest country in the world, can and should do its part to address the displacement crisis through a welcoming and generous policy for receiving and integrating humanitarian migrants into society and the workforce.

The immediate solution that will protect all workers – immigrant and U.S.-born – is to quickly provide work permits to recent arrivals—as political, business, and labor leaders have called for—which will raise wages and improve labor standards

The main economic challenge we now face due to problems in our immigration system is that many migrant workers who have recently arrived in the United States are not able to quickly obtain employment authorization documents, also known as EADs or work permits—which would allow them to be employed lawfully in the United States. Having a valid work permit and working lawfully would in turn allow the beneficiary to support themselves and their families, taking pressure off the shelter system and charities such as food banks who have been providing temporary assistance while migrants go through the adjudication process or wait for the statutorily mandated wait times to pass before they can apply for a work permit. Not having a work permit, on the other hand, means that migrant workers do not have the right to work—and if they work unlawfully in order to survive—they have no labor and workplace rights that are enforceable in practice, even if they have some rights on paper (such as the right to be paid the minimum wage).

At present, as countless news reports have covered, there are many migrant workers seeking employment but lacking authorization, and large numbers of employers are hoping to hire them.21 Just last week, over 100 top executives wrote an open letter to President Biden asking him to facilitate quick access to work permits for asylum-seekers.22

Numerous state and local political leaders are also calling on the Biden administration to explore solutions to quickly get work permits into the hands of migrant workers.23

And perhaps most notably, it’s important to acknowledge what labor unions—the organizations that represent millions of working people, most of whom are U.S. citizens—are saying about the same asylum-seekers who wish to work legally. Rather than decry that asylum-seekers and other recent arrivals are “stealing jobs” or negatively impacting wages and working conditions for U.S. workers, they are instead calling on the Biden administration to issue new designations of TPS where warranted and to redesignate previous TPS countries, in part because those who qualify could get quicker access to work permits.24

All immigration pathways, including our refugee and asylum systems, can be vehicles for economic growth and workforce expansion. And there’s ample research to support the assertion that wage gains result from getting work authorization—the evidence on this is clear. Work authorization also benefits U.S. workers, too, because bargaining power to improve wages and working conditions is diminished when your boss can break the law with impunity by under-paying your coworkers who don’t have a work permit, and who can’t safely complain to the Labor Department because they fear retaliation and deportation.

Legitimate criticisms of the immigration system exist and there are obvious policy solutions to fix them that would protect U.S workers and migrant workers

In recent decades, far too much of our immigration policy apparatus has ignored the interests of workers—immigrants and U.S.-born workers alike. This apparatus has instead been weaponized to suppress wages for employers’ gain. Immigration is an area of policy where a few simple solutions could result in major improvements to labor standards for all workers—but these solutions are blocked by low-road employers who benefit from today’s anti-worker system and lobby Congress to prevent the obvious needed solutions. And today, many policymakers—rather than focusing their efforts on achieving the needed solutions—are instead pushing policies that would make things worse for U.S. workers, by leaving more workers vulnerable and exploitable, and instead of raising wages, would mostly serve to enrich private corporations that manage immigration prisons and profit from draconian immigration enforcement laws.

To be clear, the challenge posed to U.S. workers is not the simple presence of migrant workers in the labor market; instead, it is the legal framework that makes these workers exploitable. A 2017 comprehensive study conducted by a number of prominent scholars for the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine found that levels of immigration have only very small impacts on wages and employment.25 However, in certain local labor markets and industries where a significant share of workers are migrants who do not have access to worker protections and basic labor rights—either because they are unauthorized immigrant workers or because they are migrants employed through nonimmigrant, temporary work visa programs—the migrant workers’ lack of rights makes it difficult for them to bargain effectively for decent wages, and their weak leverage spills over to undercut the leverage of U.S. workers—i.e., citizens and immigrants who are lawful permanent residents.

Some industries have sought out unauthorized immigrant workers because of this vulnerability created by their lack of an immigration status. Various analyses of the August 2019 worksite raids on Mississippi poultry plants by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) have served to remind us of that fact.26 In the case of temporary migrant workers, employers and industry groups spend millions lobbying to expand the number of exploitative visas that are available and to deregulate the rules governing those visas.27 In doing so, they are able to undercut the wage-boosting potential of the low unemployment rate and strong job growth.

Unauthorized immigrants are easily exploited by employers

Unauthorized immigrants, who make up nearly 5% of the U.S. labor force, contribute to the economy in vital industries and pay billions in taxes and contributions to the social safety net.28 But these eight million workers are not fully protected by U.S. labor laws because of their precarious immigration status: Unauthorized workers are often afraid to complain about unpaid wages and substandard working conditions because employers can retaliate against them by taking actions that can lead to their deportation. That also makes it difficult for unauthorized immigrants to join unions and help organize workers. This imbalanced relationship gives employers extraordinary power to exploit and underpay these workers, ultimately making it more difficult for similarly situated U.S. workers to improve their wages and working conditions.

The exploitation described here is not theoretical. A landmark study and survey of 4,300 workers in three major cities found that 37.1% of unauthorized immigrant workers were victims of minimum wage violations, as compared with 15.6% of U.S.-born citizens. Further, an astounding 84.9% of unauthorized immigrants were not paid the overtime wages they worked for and were legally entitled to.29

Temporary migrant workers are also vulnerable and employers game the system

One of the main authorized or “legal” pathways for migrants who want to work in the United States is via “nonimmigrant” visas that authorize temporary employment. The United States issues hundreds of thousands of nonimmigrant visas to workers from abroad every year in an alphabet soup of temporary work visa programs.30 More than 2 million temporary migrant workers were employed in the United States in 2019 through work visa programs, accounting for roughly 1% of the labor force at the time.31 Although they are legally authorized to work, temporary migrant workers are among the most exploited laborers in the U.S. workforce because the employment relationship created by the visa programs leaves workers powerless to defend and uphold their rights.

The abuses often start before these workers even arrive in the United States—many are required to pay exorbitant fees to labor recruiters to secure U.S. employment opportunities, even though such fees are usually illegal.32 Those fees leave them indebted to recruiters or third-party lenders, which can result in a form of debt bondage.33 After arriving in the United States, temporary migrant workers may find out the job they were promised doesn’t exist.34 And in a number of cases, they have become victims of human trafficking—with some being forced to work in the sex industry.35

It’s not just farmworkers and other temporary migrant workers in low-wage jobs who are suffering from the epidemic of fees, shady recruiters, and trafficking in temporary work visa programs: College-educated workers in computer occupations, as well as teachers and nurses, have been victimized and put in “financial bondage” by recruiters and staffing firms that steal wages and file lawsuits against workers if they try to quit.36

Temporary migrant workers who are in debt are anxious to earn enough to pay back what they owe and hopefully make a profit, and are thus unlikely to rock the boat at work when things go wrong on the job. But even temporary migrant workers who aren’t caught in the debt trap are still subject to exploitation once they are working in the United States. Like unauthorized immigrants, temporary migrant workers have good reason to fear retaliation and deportation if they speak up about wage theft, workplace abuses, or other working conditions like substandard health and safety procedures on the job—not because they don’t have a valid immigration status, but because their visas are almost always tied to one employer who owns and controls their visa status. That visa status is what determines the worker’s right to remain in the country; if they lose their job, they lose their visa and become deportable. This arrangement results in a form of indentured servitude.37 Further, employers can punish them for speaking out by not rehiring them the following year or by telling recruiters in countries of origin that they shouldn’t be hired for other job opportunities in the United States (effectively blacklisting them).38

The specter of retaliation makes it understandably difficult for temporary migrant workers to complain to their employers and to government agencies about unpaid wages and substandard working conditions. Private lawsuits against employers who break the law are also an unrealistic avenue for enforcing the rights of temporary migrant workers, for two reasons: First, most are not eligible for federally funded legal services under U.S. law, and second, those who have been fired are unlikely to have a valid immigration status permitting them to stay in the United States for long enough to pursue their claims in court.

Because of these conditions, temporary work visa programs have been dubbed “close to slavery,” and government auditors have noted that increased protections are needed for temporary migrant workers.39

Another important flaw in the system is that many temporary migrant workers can be legally underpaid, and there is abundant evidence that the laws and regulations governing major temporary work visa programs—such as H-2B and H-1B—permit employers to pay their temporary migrant workers much less than the local average wage for the jobs they fill.40 And most work visa programs have no minimum or prevailing wage rules at all—maybe that’s why some employers think they can get away with vastly underpaying their temporary migrant employees, as one Silicon Valley technology company in Fremont, California, did by paying less than $2 an hour to skilled migrant workers from India on L-1 visas who were working up to 122 hours per week installing computers.41

While employers are still required by law to pay temporary migrant workers at least the state or federal minimum wage, that’s often far less than the true market rate, or the local average wage, for the occupation they’re employed in. The company employing the L-1 workers in Fremont who were paid less than $2 an hour got in trouble because California law required that they be paid no less than $8 an hour (the state minimum wage at the time) plus time-and-a-half for overtime. But the average wage in Fremont for the job they were employed in—installing computers—was $20 per hour at the time according to U.S. Department of Labor data, and if they were also configuring the computers for the company’s network, they deserved to be paid $44 per hour.42 In the end, the company was required to pay back wages of $40,000 plus a fine of $3,500 “because of the willful nature of the violations”—a slap on the wrist considering the egregiousness of the wage theft and hardly a disincentive against future violations.43

In essence, these visa programs are intentionally designed to create a labor market monopsony for employers—awarding employers greater leverage over their workers44—and growing research has shown that even modest amounts of employer monopsony power are utterly corrosive to workers’ ability to bargain for better wages.45

In addition, visa program rules make it easy for employers to avoid hiring U.S. workers in favor of exploitable and underpaid temporary migrant workers. While two of the major U.S. work visa programs require that employers first recruit U.S. workers and offer them jobs before hiring temporary migrant workers, the vast majority of the programs have no such requirement. That means that employers hiring through large work visa programs like the J-1, L-1, and H-1B can bypass the local workforce altogether when hiring migrant workers, regardless of whether the local area is experiencing high unemployment.46

Even when employers are required to recruit locally, many go to great lengths to avoid employing U.S. workers—preferring to hire temporary migrant workers because they can be more easily exploited.47 As the New York Times, Washington Post, and Vox have reported, some of former President Trump’s own companies took measures to avoid hiring local U.S. workers so they could hire temporary migrant workers instead.48

When rules requiring recruitment of U.S. workers aren’t in place, sometimes the abuses are even more egregious. There are many documented cases in which hundreds of U.S. technology workers were replaced with workers on H-1B visas earning tens of thousands of dollars less per year—and the U.S. workers were required to train their H-1B replacements to do their old jobs as a condition of receiving severance pay.49

Oversight is lacking in temporary work visa programs

There is also very little oversight of temporary work visa programs. Most of the programs have no rules in place at all to protect temporary migrant workers after they arrive in the United States. Where such rules are in place, enforcement is woefully inadequate—and companies that are frequent and extreme violators of these rules are often allowed to continue hiring through visa programs with impunity.50

Considering how these programs operate and the situation they leave temporary migrant workers in, perhaps it is no surprise that ostensibly legal workers with visas in low-wage jobs earn approximately the same low wages on average that unauthorized immigrant workers do for similar jobs, despite the fact that unauthorized workers have virtually no rights in practice.51 In other words, these workers have no financial incentive to work legally through visa programs since there is no wage premium for it—and, in fact, authorized temporary migrant workers can end up worse off economically than unauthorized workers because of the debts they incur through fees paid to recruiters.

Labor standards enforcement agencies are underfunded and understaffed

The Wage and Hour Division is responsible for enforcing provisions of several federal laws related to minimum wage, overtime pay, child labor, federal contract workers, work visa programs, migrant and seasonal agricultural workers, family and medical leave, and more. Yet, despite this broad portfolio and the nearly 165 million workers who are covered by these protections,52 funding for WHD has not kept pace with the growth of the U.S. labor force.

Figure B shows that, in inflation-adjusted 2022 dollars, WHD’s budget in 2006 was $241 million, and in 2022, $246 million—an increase of just $5 million over nearly two decades. Lack of funding for WHD reflects the general decline in overall labor standards enforcement spending across the federal government from $2.4 billion in 2012 to $2.1 billion in 2021 (in 2021 dollars).53

In 2022, funding for the Wage and Hour Division was roughly the same as in 2006: Funding for the Wage and Hour Division in the U.S. Department of Labor, fiscal years 2006–2022

| Fiscal Years | Annual funding for the Wage and Hour Division |

|---|---|

| 2006 | $241,049,000 |

| 2007 | $245,012,000 |

| 2008 | $239,318,000 |

| 2009 | $263,988,000 |

| 2010 | $306,124,000 |

| 2011 | $296,769,000 |

| 2012 | $289,918,000 |

| 2013 | $270,742,000 |

| 2014 | $277,550,000 |

| 2015 | $280,988,000 |

| 2016 | $277,410,000 |

| 2017 | $271,569,000 |

| 2018 | $265,107,000 |

| 2019 | $262,106,000 |

| 2020 | $273,570,000 |

| 2021 | $265,686,000 |

| 2022 | $246,000,000 |

Note: Dollar amounts reported have been adjusted for inflation to constant 2022 dollars using the CPI-U-RS. As a result, the dollar amounts presented here may differ from the amounts reported in the source data.

Source: Department of Labor, Budget, Performance, and Planning reports, fiscal years 2008-2022, available at https://www.dol.gov/general/budget, accessed February 27, 2023.

Yet, in addition to the lack of funding and the nearly 165 million workers WHD has a mandate to protect, the number of WHD investigators that the agency employs, who are primarily responsible for ensuring that federal wage and hour laws are obeyed by employers across all 50 states and U.S. territories, is near an all-time low.

Figure C shows that there were only 810 WHD investigators at the end of November 2022 to enforce all federal wage and hour laws, two fewer than in 1973, the first year for which data are available, and 422 fewer than the peak year of 1978, when there were 1,232 WHD investigators. Meanwhile, the number of workers that WHD has a mandate to protect has increased sharply. The average number of WHD-covered workers in 2022 was 164.3 million, which amounts to 202,824 workers for every wage and hour investigator. Compare this to 1973, when there were 72,588 covered workers for every wage and hour investigator.54 Investigators are now responsible for almost triple the number of workers than in 1973 (2.8 times more).

Number of federal wage and hour investigators is near its historic low: Number of Wage and Hour Division investigators, U.S. Department of Labor, 1973–2022

| Year | Investigators on board at year’s end |

|---|---|

| 1973 | 812 |

| 1974 | 869 |

| 1975 | 921 |

| 1976 | 964 |

| 1977 | 980 |

| 1978 | 1,232 |

| 1979 | 1,087 |

| 1980 | 1,059 |

| 1981 | 953 |

| 1982 | 914 |

| 1983 | 928 |

| 1984 | 916 |

| 1985 | 950 |

| 1986 | 908 |

| 1987 | 951 |

| 1988 | 952 |

| 1989 | 970 |

| 1990 | 938 |

| 1991 | 865 |

| 1992 | 835 |

| 1993 | 804 |

| 1994 | 800 |

| 1995 | 809 |

| 1996 | 781 |

| 1997 | 942 |

| 1998 | 942 |

| 1999 | 938 |

| 2000 | 949 |

| 2001 | 945 |

| 2002 | 898 |

| 2003 | 850 |

| 2004 | 788 |

| 2005 | 773 |

| 2006 | 751 |

| 2007 | 732 |

| 2008 | 731 |

| 2009 | 894 |

| 2010 | 1,035 |

| 2011 | 1,024 |

| 2012 | 1,067 |

| 2013 | 1,040 |

| 2014 | 976 |

| 2015 | 995 |

| 2016 | 974 |

| 2017 | 912 |

| 2018 | 835 |

| 2019 | 780 |

| 2020 | 823 |

| 2021 | 782 |

| 2022 | 810 |

Note: Numbers represent Wage and Hour Division investigators on staff at the end of each fiscal year (the federal government's fiscal year runs from October 1 to September 30), except for 2022, which represents the number of investigators on staff at the end of November 2022.

Sources: Author’s analysis of Wage and Hour Division (WHD) data on number of investigators from unpublished Excel files provided by WHD staff members to the author. Source for 2020 and 2021 is Rebecca Rainey, “Wage-Hour Investigator Hiring Plans Signal DOL Enforcement Drive,” Bloomberg Law, January 28, 2022. Source for 2022 is Rebecca Rainey, "Wage Division Enforcement Declines Again in Wake of Hiring Woes," Bloomberg Law, Decemer 28, 2022.

Another issue related to the funding and staffing challenges has reportedly been WHD’s “issues with recruiting and retaining employees.” Bloomberg Law reported in December 2022 that WHD has “struggled to recruit new investigative staff” and WHD’s overall back wages recovered, employees who received back wages, and total number of hours spent on investigations “all dropped in fiscal year 2022 compared to the year prior” according to WHD data.55 Despite WHD’s stated intention to hire 100 new investigators in the Biden administration, a heavy workload and inadequate funding from Congress appear to be hindering WHD from hiring enough staff for the tasks at hand.

Immigration is the government’s top federal law enforcement priority while labor standards enforcement agencies are starved for funding and too understaffed to adequately protect workers

Since this hearing purports to make the connection between immigration and labor, it must be noted how Congress has heavily prioritized the enforcement of immigration laws—much to the detriment of labor and employment laws—as evidenced by the massive imbalance in appropriations made to enforce each. For too long, employers have lobbied members of Congress to keep funding levels unrealistically and disastrously low for agencies like the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) and the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB)—so low that they cannot adequately fulfill their missions. The result is an environment of near impunity for rampant violators of labor and wage and hour laws, a situation brought to light by the recent wave of labor organizing across the country as workers make it clear that they are unwilling to continue accepting unsafe and unjust conditions on the job.

“Budgets are moral documents,”56 and one clear way to understand the priorities of a government is to look at how it spends money. For at least the past decade, the U.S. Congress has placed little value on worker rights and working conditions. A recent comparative analysis I published of federal budget data from 2012 to 2021 reveals that the top federal law enforcement priority of the United States is to detain, deport, and prosecute migrants, and to keep them from entering the country without authorization.57 Protecting workers in the U.S. labor market—by ensuring that their workplaces are safe and that they get paid every cent they earn—is barely an afterthought.

My research shows that the wide gap in government funding between immigration and labor standards enforcement has persisted for at least a decade. Government spending on immigration enforcement in 2021 was nearly 12 times the spending on labor standards enforcement—despite the mandate of the labor agencies to protect the 165 million workers employed at nearly 11 million workplaces.58 Labor standards enforcement agencies across the federal government received only $2.1 billion in 2021. (See Figure D.)

Government funding for immigration enforcement was nearly 12 times as much as labor standards enforcement funding in 2021: U.S. government funds appropriated for immigration and labor standards enforcement, 2021

| Immigration enforcement | Labor standards enforcement | |

|---|---|---|

| 2021 | $25.0 | $2.1 |

Notes: Values are adjusted to constant 2021 dollars and reflect totals for the U.S. government’s fiscal year (October 1 to September 30).

Notes: Values are adjusted to constant 2021 dollars and reflect totals for the U.S. government’s fiscal year (October 1 to September 30). The immigration enforcement total for 2021 includes funding for U.S. Customs and Border Protection, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and the Office of Biometric Identity Management. Totals for labor standards enforcement include appropriations for all subagencies, administrations, and offices of the U.S. Department of Labor considered for “worker protection” in budget documents, including the Employee Benefits Security Administration, Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs, Wage and Hour Division, Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs, Office of Labor-Management Standards, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Mine Safety and Health Administration, and the Office of the Solicitor, in addition to two other agencies not within the Department of Labor: the National Labor Relations Board and the National Mediation Board.

Sources: U.S. Department of Labor, Fiscal Year 2023—Department of Labor, Budget in Brief and Archived Budgets, fiscal years 2012–2022; National Mediation Board, Congressional Justifications, fiscal years 2014–2023; National Labor Relations Board, Performance Budget Justification, fiscal years 2012–2023; and U.S. Department of Homeland Security, DHS Budget, Congressional Budget Justification for Fiscal Years 2012–2023.

The appropriations story is largely the same over the past decade and across three presidential administrations. In 2012—a decade ago—Congress appropriated $21.4 billion for immigration enforcement but only $2.4 billion for labor standards enforcement (in constant 2021 dollars). The average annual amount appropriated for immigration enforcement funding over the past decade was $23.4 billion, while the average for labor standards enforcement was $2.2 billion.59

Federal budget data also show that labor enforcement agencies are staffed at only a fraction of the levels required to adequately fulfill their missions, with the 10 labor standards enforcement agencies combined only having enough funding to employ fewer than 9,400 personnel, while the immigration enforcement agencies received enough funds to employ a total of almost 79,000 personnel, more than eight times as many personnel as the labor standards agencies.

This funding and staffing situation leaves migrant workers especially vulnerable to employer lawbreaking. There are not enough federal agents to police employers, while a massive immigration enforcement dragnet threatens workers with deportation. Employers take advantage of the climate of fear this creates to prevent workers from reporting workplace abuses. Workers who find the courage to speak up can be retaliated against in ways that can set the deportation process in motion.

Proposed solutions and reforms to improve labor standards for American and immigrant workers

In sum, the bargaining power of U.S. workers is undercut when millions of unauthorized workers and temporary migrants—together accounting for roughly 6% of the U.S. labor force—are underpaid by employers and cannot safely complain to the Department of Labor or sue employers that exploit them.

The previous administration pushed a bigoted and xenophobic narrative that pitted immigrants against native-born workers under the false premise that the economy is a zero-sum game with a fixed number of jobs. This leads to predictably foolish and cruel policies—such as more and bigger worksite raids by ICE—that don’t improve conditions for workers but only serve to increase the power employers have over workers.60 A better and more humane response starts from realizing how much of today’s immigration policy is driven by low-road employers who aim to benefit at the expense of both migrants and U.S. workers. From this perspective, one can see that improving labor standards for migrants who lack work authorization, as well as temporary migrant workers, will lift the floor for all workers, which will increase bargaining power and raise wages.

The most transformative solutions require congressional action, but the Biden administration can also make significant reforms on its own. First and foremost, Congress should pass legislation granting lawful permanent resident (LPR) status to the current unauthorized immigrant population; this would include recipients of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals and those who currently have Temporary Protected Status. Granting LPR status to workers without status, or even simply providing work authorization, would raise their wages and improve labor standards for all similarly situated workers.61

Congress could also reform temporary work visa programs, which are a major component of the U.S. employment-based immigration system. Congress could do so by:

- Updating, simplifying, and standardizing the rules for all work visa programs:

- First, by requiring employers to recruit and offer jobs to qualified U.S. workers,

- and second, in cases where employers can’t find U.S. workers, ensuring that all temporary migrant workers are paid no less than the local average wage for the job and are not tied to a single employer.

- Limiting the time that temporary migrant workers are in a temporary status by allowing them to self-petition for permanent residence after a short provisional period.62

- Passing laws permanently banning any employer from hiring through temporary work visa programs if that employer has a record of violating labor or employment laws (although in some cases a screening process for this could also be achieved via regulation).63

- Appropriating more funding to the Department of Labor to enforce this new system and audit employers after migrant workers have been hired.

Congress should also prioritize reintroduction and passage of the Protect Our Workers from Exploitation and Retaliation (POWER) Act, perhaps the single most important piece of legislation aimed at protecting workers of all immigration statuses from the threat of employer retaliation and deportation. The POWER Act—last introduced in March of this year by Rep. Judy Chu (D-Calif.) and Ranking Member of the full Education and Workforce Committee, Rep. Bobby Scott (D-VA),64 and in the Senate in 2019 by Sen. Robert Menendez (D-N.J.), and which is supported by various unions and migrant worker advocacy organizations—would expand access to humanitarian “U” visas for migrant workers who report workplace violations. (U visas are currently available to victims of certain qualifying crimes who are cooperating in a related investigation or prosecution; the POWER Act would increase the number of U visas available and extend eligibility to labor-related crimes.) The POWER Act would also strengthen the investigative powers of labor standards enforcement agencies. Finally, it would permit postponing the deportation of migrant workers who file a bona fide workplace claim or are a material witness to one, so they can remain in the country to pursue it; they would also be eligible for employment authorization so they could work during that time.

Congress can and should also pass several pieces of legislation that would improve wages and working conditions and labor standards for all workers, across all demographics and regardless of country of birth or immigration status. These include:

- The Raise the Wage Act, which would gradually raise the federal minimum wage to $17 an hour by 2028. The bill would also gradually raise and then eliminate subminimum wages for tipped workers, workers with disabilities, and youth workers. Raising the federal minimum wage to $17 by 2028 would impact 27,858,000 workers across the country, or 19% of the U.S. workforce. The increases would provide an additional $86 billion annually in wages for the country’s lowest-paid workers, with the average affected worker who works year-round receiving an extra $3,100 per year.65

- The Protect the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, which would strengthen workers’ rights to form a union and negotiate with their employers for better wages and working conditions. Specifically, it would reform our nation’s labor law so that private-sector employers can’t perpetually stall union elections and contract negotiations and coerce and intimidate workers seeking to unionize.66

- The Fairness for Farmworkers Act, which would allow farmworkers to be entitled to time-and-a-half pay after working for more than 40 hours in a week, thus ending the discriminatory denial of overtime pay and most of the remaining minimum wage exemptions for agricultural workers under the Fair Labor Standards Act.67 While some people may mistakenly believe that nearly all farmworkers are immigrants, the reality is that 30% are U.S.-born citizens. Thus, the bill would end the exclusion of basic wage and hour protections for not just immigrants working in agriculture, but many Americans, too.

- The Asunción Valdivia Heat Illness, Injury and Fatality Prevention Act, which, as the bill’s authors describe, “would direct the Department of Labor’s (DOL’s) Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to establish a permanent, federal standard to protect workers against occupational exposure to excessive heat, both in indoor and outdoor environments.”68 The bill is modeled after the heat standard law in California, which one study showed has resulted in 30% fewer heat-related illnesses and injuries.69

- The Combating Child Labor Act, which would establish harsher civil and criminal penalties, including new criminal penalties, for violations of existing child labor laws and increase transparency regarding violations through a mandated report from DOL to Congress that reveals public information about the companies that are directly benefiting from illegal child labor.70

These legislative proposals, which contain policies that will help all workers and lift standards across the board, are some of the best ways to improve wages and working conditions for all and ensure a fair economy for all. In fact, passing stronger labor and workplace protections like these, and supporting workers’ rights to organize, is undoubtedly the best way to lock in and solidify, and expand, economic gains.

And finally, in order to improve employer compliance with wage and hour laws and better protect both U.S. workers and migrant workers, as discussed earlier in this section, Congress must appropriate more funding to labor standards enforcement agencies like the Wage and Hour Division. Agencies like WHD, OSHA, and the NLRB need more investigators, agents, and lawyers, which require a sharp increase in funding. Marty Walsh, the previous Labor Secretary, recently expressed a similar sentiment to the Washington Post with respect to the Wage and Hour Division, noting that he hoped Congress would provide “more money for enforcement officers…[because] you can’t handle the number of complaints if you don’t have the number of officers.”71

1. See for example, Joel Rose and Marisa Peñaloza, “Migrants are frustrated with the border app, even after its latest overhaul,” NPR Weekend Edition Saturday, May 12, 2023.

2. Bree Samuels, “White House asks Congress for $40 Billion in additional funding,” The Hill, August 10, 2023.

3. Jesse Franzblau, “Congress Should Reject The White House’s Supplemental Funding Requests For Increased Immigration Detention, Border Militarization, And Surveillance,” National Immigrant Justice Center, August 14, 2023.

4. See discussion at Figure 3 in Testimony of Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, Policy Director, American Immigration Council. “The Border Crisis: Is the Law Being Faithfully Executed?” A hearing in Subcommittee on Immigration Integrity, Security, and Enforcement, Committee on the Judiciary, U.S. House of Representatives, June 7, 2023.

5. Rep. Good, “Chairman Good to Hold Hearing on the Impact of Illegal Immigration on America’s Workforce,” Committee on Education and the Workforce, House of Representatives, Press Release, September 6, 2023.

6. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Foreign Born Workers: Labor Force Characteristics—2022,” U.S. Department of Labor, News Release, May 18, 2023.

7. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Foreign Born Workers: Labor Force Characteristics—2022,” U.S. Department of Labor, News Release, May 18, 2023.

8. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Foreign Born Workers: Labor Force Characteristics—2022,” U.S. Department of Labor, News Release, May 18, 2023.

9. Julia Gelatt, “Immigrant Workers: Vital to the U.S. COVID-19 Response, Disproportionately Vulnerable,” Fact Sheet, Migration Policy Institute, March 2020.

10. David Dyssegaard Kallick and Anthony Capote, Immigrants in the U.S. Economy: Overcoming Hurdles, Yet Still Facing Barriers, Immigration Research Initiative, May 1, 2023.

11. David Dyssegaard Kallick and Anthony Capote, Immigrants in the U.S. Economy: Overcoming Hurdles, Yet Still Facing Barriers, Immigration Research Initiative, May 1, 2023.

12. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Unemployment Rate [UNRATE], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UNRATE, September 8, 2023.

13. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Job Openings: Total Nonfarm [JTSJOL], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/JTSJOL, September 8, 2023.

14. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Force Participation Rate – 25-54 Yrs. [LNS11300060], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LNS11300060, September 8, 2023, and, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment-Population Ratio – 25-54 Yrs. [LNS12300060], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LNS12300060, September 8, 2023.

15. Elise Gould and Ismael Cid-Martinez, “2022 Census data preview: Poverty rates expected to increase as high inflation and the loss of safety net programs overshadow labor market improvements,” Working Economics blog (Economic Policy Institute), September 8, 2023.

16. Elise Gould, “The equalizing effect of strong labor markets: Explaining the disproportionate rise in the Black employment-to-population ratio,” Working Economics blog (Economic Policy Institute), July 17, 2023.

17. Elise Gould and Ismael Cid-Martinez, “2022 Census data preview: Poverty rates expected to increase as high inflation and the loss of safety net programs overshadow labor market improvements,” Working Economics blog (Economic Policy Institute), September 8, 2023.

18. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Figures at a Glance, June 14, 2023.

19. Jeff Mason and Julia Symmes Cobb, “Biden thanks Colombia for hosting Venezuelan refugees, eyes deeper partnership,” Reuters, April 20, 2023.

20. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Costa Rica, Country Operations.

21. See for example, Laura Rodríguez Presa, Talia Soglin and Nell Salzman, “As asylum-seekers struggle while waiting for work permits, Chicago businesses can’t fill jobs,” Chicago Tribune, July 16, 2023 and Angelika Albaladejo, “As influx of people from Latin America continues, Colorado leaders want more migrants in temporary jobs,” Denver7.com, July 31, 2023.

22. Rafael Bernal, “Industry execs press Biden for more funding for New York migrant influx,” The Hill, August 29, 2023.

23. See for example, Katelyn Cordero, “‘Let them work’: Hochul pressures Biden over New York’s migrant surge,” Politico, August 24, 2023..

24. America’s Voice, “Ahead of Labor Day: Business, Labor and Policymakers Call for Work Permits and TPS,” Press Release, August 31, 2023.

25. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration (Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2017).

26. See, for example, Eric Schlosser, “Why It’s Immigrants Who Pack Your Meat,” The Atlantic, August 16, 2019; Robin Young, “A History of Hispanic Immigrants in Mississippi’s Poultry Industry,” Here and Now, WBUR, August 12, 2019.

27. See, for example, Tony Romm, “Apple, Amazon, Facebook and Google Spent Nearly $50 Million—a Record—to Influence the U.S. Government in 2017,” Vox, January 23, 2018; Devjyot Ghoshal, “2017 India’s IT Trade Body Spent a Record Sum Lobbying the US Congress Before the H-1B Crackdown,” Quartz India, April 7, 2017.

28. Jens Manuel Krogstad, Jeffrey S. Passel, and D’Vera Cohn, “5 Facts About Illegal Immigration in the U.S.,” FactTank (Pew Research Center), June 12, 2019; Lisa Christensen Gee, Matthew Gardner, Misha Hill, and Meg Wiehe, Undocumented Immigrants’ State and Local Tax Contributions, Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy, updated March 2017. .

29. Annette Bernhardt et al., Broken Laws, Unprotected Workers: Violations of Employment and Labor Laws in America’s Cities, Center for Urban Economic Development, National Employment Law Project, and UCLA Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, 2009.

30. Jill H. Wilson, Nonimmigrant (Temporary) Admissions to the United States: Policy and Trends, Congressional Research Service, December 2017.

31. Daniel Costa, Temporary Work Visa Programs and the Need for Reform: A Briefing on Program Frameworks, Policy Issues and Fixes, and the Impact of COVID-19, Economic Policy Institute, February 3, 2021.

32. See for example, Centro de los Derechos del Migrante, Recruitment Revealed: Fundamental Flaws in the H-2 Temporary Worker Program and Recommendations for Change, n.d.

33. United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, “End of Visit Statement, United States of America (6–16 December 2016) by Maria Grazia Giammarinaro, UN Special Rapporteur in Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children,” Washington, D.C., December 19, 2016. See also United Nations Office of the High Commisioner for Human Rights, “Debt Bondage Remains the Most Prevalent Form of Forced Labour Worldwide—New UN Report” (press release), September 15, 2016; United Nations Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Slavery, Including Its Causes and Consequences, Thirty-third session, Agenda item 3, Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development, July 4, 2016; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, The Role of Recruitment Fees and Abusive and Fraudulent Practices of Recruitment Agencies in Trafficking in Persons, 2015.

34. See for example, Steven Greenhouse, “Low Pay and Broken Promises Greet Guest Workers,” New York Times, February 28, 2007.

35. Liam Stack, “Indian Guest Workers Awarded $14 Million,” New York Times, February 18, 2015; Jessica Garrison, Ken Bensinger, and Jeremy Singer-Vine, “The New American Slavery,” BuzzFeed News, July 24, 2015; U.S. Department of Justice, “Miami Beach Sex Trafficker Sentenced to 30 Years in Prison for International Trafficking Scheme Targeting Foreign University Students” (press release), U.S. Attorney’s Office, Southern District of Florida, March 24, 2017; Holbrook Mohr, Mitch Weiss, and Mike Baker, “U.S. Impact: U.S. Fails to Tackle Student Abuses,” Associated Press, December 6, 2010.

36. See for example, Matt Smith, Jennifer Gollan, and Adithya Sambamurthy, “Job Brokers Steal Wages, Entrap Indian Tech Workers in US,” Reveal News, Oct. 27, 2014; Farah Stockman, “Teacher Trafficking: The Strange Saga of Filipino Workers, American Schools, and H-1B Visas,” Boston Globe, June 12, 2013; Tom McGhee, “Kizzy Kalu Lured Nurses to U.S. with Promises of High Pay, Prosecutors Say,” Denver Post, June 4, 2013.

37. See for example, Christopher Lapinig, “How U.S. Immigration Law Enables Modern Slavery,” The Atlantic, June 7, 2017.

38. See for example, Southern Poverty Law Center, Close to Slavery: Guestworker Programs in the United States, February 2013.

39. See for example, Southern Poverty Law Center, Close to Slavery: Guestworker Programs in the United States, February 2013; U.S. Government Accountability Office, H-2A and H-2B Visa Programs: Increased Protections Needed for Foreign Workers, GAO-15-154, reissued May 2017.

40. See for example, Daniel Costa, The H-2B Temporary Foreign Worker Program: For Labor Shortages or Cheap, Temporary Labor? Economic Policy Institute, January 2016; Ron Hira, “New Data Show How Firms Like Infosys and Tata Abuse the H-1B Program,” Working Economics Blog (Economic Policy Institute), February 19, 2015; Daniel Costa, “H-2B Crabpickers Are So Important to the Maryland Seafood Industry That They Get Paid $3 Less per Hour Than the State or Local Average Wage,” Working Economics Blog (Economic Policy Institute), May 26, 2017.

41. Monte Francis, “Fremont Tech Company Paid Workers $1.21 an Hour: U.S. Dept. of Labor,” NBC Bay Area, October 22, 2014. See also George Avalos, “Workers Paid $1.21 an Hour to Install Fremont Tech Company’s Computers,” Mercury News, October 22, 2014. L-1 visa status confirmed in an email from George Avalos of the Mercury News, October 23, 2014.

42. Author’s analysis of historical data from Foreign Labor Certification Data Center, Online Wage Library, “7/2013 – 6/2014 FLC Wage Data,” https://flcdatacenter.com/Download.aspx, for Standard Occupational Classification codes 15-1142 and 49-2011, for region 36084, Oakland-Fremont-Hayward, CA Metropolitan Division (2013–2014).

43. U.S. Department of Labor, Wage and Hour Division, “US Department of Labor Investigation Finds Silicon Valley Technology Employer Owed More Than $40,000 to Foreign Workers” (press release no. 14-1717-SAN [SF-71]), October 22, 2014.

44. Bivens and Shierholz broadly define “monopsony power” as “the leverage enjoyed by employers to set their workers’ pay.” See Josh Bivens and Heidi Shierholz, What Labor Market Changes Have Generated Inequality and Wage Suppression?: Employer Power Is Significant but Largely Constant, Whereas Workers’ Power Has Been Eroded by Policy Actions, Economic Policy Institute, December 2018.

45. IZA – Institute of Labor Economics, “Monopsony Power and Guest Worker Programs,” IZA Discussion Paper no. 12096, January 2019.

46. International Labor Recruitment Working Group, Shining a Light on Summer Work: A First Look at the Employers Using the J-1 Summer Work Travel Visa, July 2019; Daniel Costa, H-1B Visa Needs Reform to Make It Fairer to Migrant and American Workers, Fact Sheet, Economic Policy Institute, April 2017.

47. See for example, Jessica Garrison, Ken Bensinger, and Jeremy Singer-Vine, “‘All You Americans Are Fired,’” BuzzFeed News, December 1, 2015.

48. Charles V. Bagli and Megan Twohey, “Donald Trump to Foreign Workers for Florida Club: You’re Hired,” New York Times, February 25, 2016; David A. Fahrenthold and Lori Rozsa, “‘Apply by Fax’: Before It Can Hire Foreign Workers, Trump’s Mar-a-Lago Club Advertises at Home—Briefly,” Washington Post, August 7, 2017; Alexia Fernández Campbell, “3 Trump Properties Posted 144 Openings for Seasonal Jobs. Only One Went to a US Worker,” Vox, February 13, 2018.

49. Julia Preston, “Pink Slips at Disney. But First, Training Foreign Replacements,” New York Times, June 3, 2015; Michael Hiltzik, “A Loophole in Immigration Law Is Costing Thousands of American Jobs,” Los Angeles Times, February 20, 2015; Ron Hira, “New Data Show How Firms Like Infosys and Tata Abuse the H-1B Program,” Working Economics Blog (Economic Policy Institute), February 19, 2015; Bill Whitaker, “Are U.S. Jobs Vulnerable to Workers with H-1B Visas?” 60 Minutes, August 13, 2017.

50. Ken Bensinger, Jessica Garrison, and Jeremy Singer-Vine, “Employers Abuse Foreign Workers. U.S. Says, by All Means, Hire More,” BuzzFeed News, May 12, 2016.

51. Lauren A. Apgar, Authorized Status, Limited Returns: The Labor Market Outcomes of Temporary Mexican Workers, Economic Policy Institute, May 21, 2015.

52. For background on WHD’s mandate and the number of workers protected by laws WHD enforces, see Wage and Hour Division, “About the Wage and Hour Division,” Fact Sheet, U.S. Department of Labor.

53. Daniel Costa, Threatening Migrants and Shortchanging Workers: Immigration Is the Government’s Top Federal Law Enforcement Priority, While Labor Standards Enforcement Agencies Are Starved for Funding and Too Understaffed to Adequately Protect Workers, Economic Policy Institute, December 15, 2022.

54. To derive this estimate, the number of covered workers in 1973 and 2022 was divided by the number of WHD investigators in those years. The number of covered workers is derived from the annual averages reported for the total civilian labor force, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey, Series Id: LNU01000000, Not Seasonally Adjusted, Series title: (Unadj) Civilian Labor Force Level, ages 16 and over [data tables], U.S. Department of Labor.

55. Rebecca Rainey, “Wage Division Enforcement Declines Again in Wake of Hiring Woes,” Bloomberg Law, December 28, 2022.

56. The origin of the phrase is unknown but it has been used regularly in the context of economic and fiscal policy debates, including by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. See, for example, Jon Wiener, “Martin Luther King’s Final Year: An Interview with Tavis Smiley,” The Nation, January 18, 2016; Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II, “Every budget is a moral document,” Twitter, @RevDrBarber, April 27, 2017, 2:37 p.m.; Scott Wong, “Begich: Budget ‘a Moral Document’,” Politico, April 11, 2011; and Dylan Matthews, “Budgets Are Moral Documents, and Trump’s Is a Moral Failure,” Vox, March 16, 2017.

57. For a full discussion see Daniel Costa, Threatening migrants and shortchanging workers: Immigration is the government’s top federal law enforcement priority, while labor standards enforcement agencies are starved for funding and too understaffed to adequately protect workers, Economic Policy Institute, December 15, 2022.

58. Author’s analysis of data on the size of the labor force and establishments from Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW), accessed October 1, 2022. Data on the number of workers represent QCEW data on the total number of employees covered by unemployment insurance programs, which is used as a proxy for the number of workers covered by labor standards enforcement agencies.

59. The estimates cited here for labor standards enforcement appropriations uses an expansive definition that includes federal budget data for fiscal years 2012 to 2021 for the eight subagencies, administrations, and offices that DOL considers for “worker protection,” in addition to the NLRB and the National Mediation Board.

60. Rebecca Smith, Ana Avendaño, and Julie Martínez Ortega, Iced Out: How Immigration Enforcement Has Interfered with Workers’ Rights, AFL-CIO, American Rights at Work Education Fund, and National Employment Law Project, October 2009.

61. See for example, Shirley J. Smith, Audrey Singer, and Roger G. Kramer, Characteristics and Labor Market Behavior of the Legalized Population Five Years Following Legalization (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Labor, Bureau of International Labor Affairs, 1996); Sankar Mukhopadhyay, “Comparing Wage Gains from Different Immigrant Legalization Programs,” IZA DP No. 11525, May 2018; Tom K. Wong, Ignacia Rodriguez Kmec, and Diana Pliego, DACA Boosts Recipients’ Well-Being and Economic Contributions: 2022 Survey Results, Center for American Progress, April 27, 2023.

62. See, for example, Demetrios G. Papademetriou, Doris Meissner, Marc R. Rosenblum, and Madeleine Sumption, Aligning Temporary Immigration Visas with U.S. Labor Market Needs: The Case for a New System of Provisional Visas, Migration Policy Institute, July 2009.

63. See discussion in Daniel Costa and Philip Martin, Record-low number of federal wage and hour investigations of farms in 2022: Congress must increase funding for labor standards enforcement to protect farmworkers, Economic Policy Institute, August 22, 2023; and Daniel Costa, As the H-2B visa program grows, the need for reforms that protect workers is greater than ever: Employers stole $1.8 billion from workers in the industries that employed most H-2B workers over the past two decades, Economic Policy Institute, August 18, 2022.

64. Congressman Bobby Scott, “Reps. Chu, Scott Re-Introduce POWER Act to Create Safe, Just Workplaces for Every Worker in America,” Press Release, March 28, 2023.

65. Ben Zipperer, The Impact of the Raise the Wage Act of 2023, Fact Sheet, Economic Policy Institute, July 25, 2023.

66. See for example, “Celine McNicholas, Margaret Poydock, and Lynn Rhinehart, “The PRO Act is pro-worker: How the act would restore workers’ freedom to form a union,” Working Economics blog (Economic Policy Institute), February 4, 2021; Celine McNicholas, Margaret Poydock, and Lynn Rhinehart, Why workers need the Protecting the Right to Organize Act: How the PRO Act solves the problems in current law that thwart workers seeking union representation, Fact Sheet, Economic Policy Institute, February 9, 2021.

67. See for example, Farmworker Justice, “The Fairness for Farm Workers Act: It’s Time to End Discrimination against Farmworkers,” Fact Sheet, July 2023.

68. Rep. Alma Adams, “Adams, Labor Leaders Introduce Heat Stress Legislation to Protect Workers,” Press Release, July 26, 2023.

69. R. Jisung Park, Nora Pankratz, A. Patrick Behrer, Temperature, workplace safety, and labor market inequality, The Washington Center for Equitible Growth, July 19, 2021.

70. Rep. Dan Kildee, “Kildee leads news bill to crack down on child labor in America,” Press Release, July 26, 2023.

71. Theodoric Meyer, “An Exit Interview with Labor Secretary Marty Walsh,” The Washington Post, March 3, 2023.