Members of the committee, thank you for allowing me to speak with you today. My name is David Cooper. I am a senior analyst at the Economic Policy Institute (EPI). EPI is a nonpartisan, nonprofit research organization in Washington, D.C., whose mission is to analyze the economy through the lens of the typical U.S. working family. EPI researches, develops, and advocates for public policies that help ensure the economy provides opportunity and fair rewards for all Americans, with a focus on policies to support low- and middle-income households.

I am testifying in support of SB 15, which would gradually raise the Delaware minimum wage from the current $9.25 per hour to $15 per hour by 2025. In my testimony I will discuss why $15 in 2025 is an appropriate level for Delaware’s minimum wage and the impact it will have on the state’s low-wage workforce. I will briefly summarize what economic research tells us about how higher minimum wages affect workers, employers, and the broader economy. Finally, I will discuss why now is a good time to raise the state’s minimum wage, particularly as an end to the COVID-19 pandemic may be on the horizon.

Background and appropriateness of a Delaware minimum wage of $15 in 2025

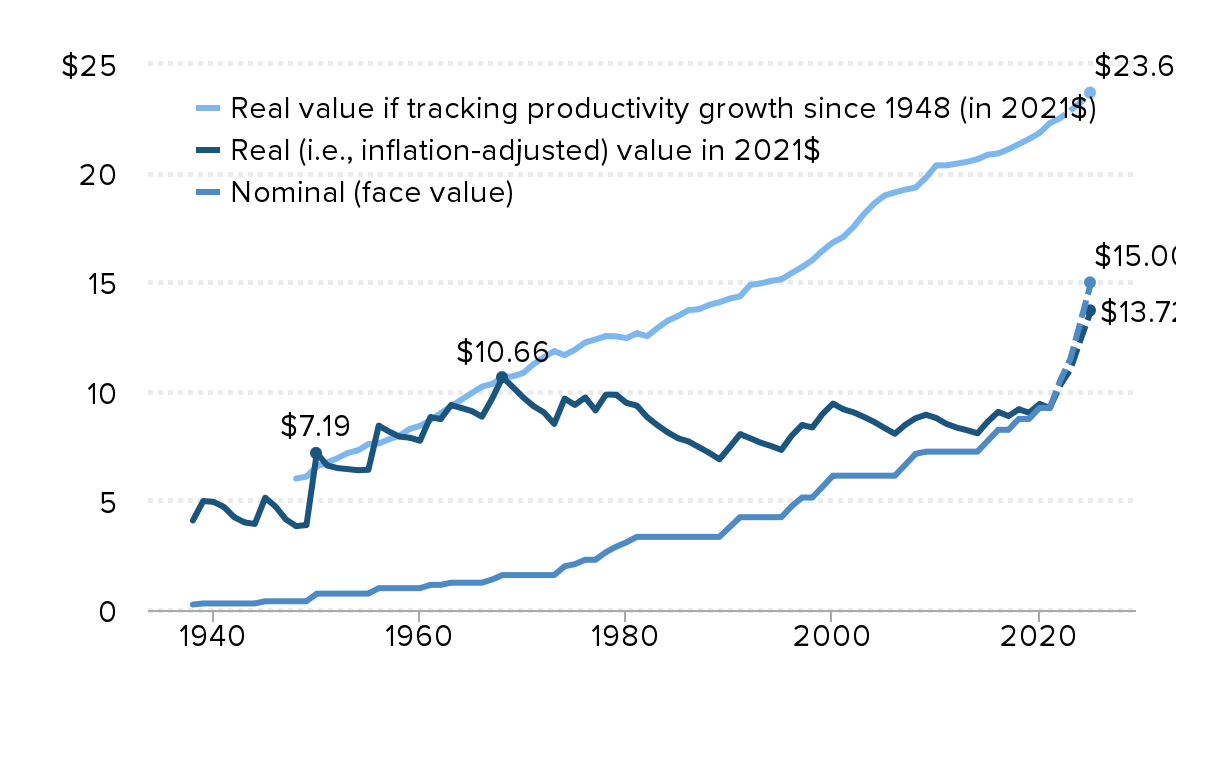

Figure A shows the nominal and real (inflation-adjusted) values of the prevailing minimum wage in Delaware since the late 1930s. From the late 1940s until the late 1960s, the federal minimum wage—which covered workers in Delaware—was raised regularly, at a pace that roughly matched growth in average U.S. labor productivity. The federal minimum wage reached an inflation-adjusted peak value in 1968 of $10.66 per hour in 2021 dollars.1 In the decades that followed, Congress made infrequent and inadequate adjustments to the federal minimum wage that never undid the erosion in value that occurred due to inflation in the 1970s and 1980s.

The economy can afford a much higher minimum wage: Real and nominal Delaware minimum wage (historical and under proposed increase to $15 in 2025) compared with productivity-tracking minimum wage

| Year | Nominal (face value) | Nominal (face value) | Real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) value in 2021$ | Projected real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) value in 2021$ | Real value if tracking productivity growth since 1948 (in 2021$) | Real value if tracking productivity growth since 1948 (in 2021$) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1938 | $0.25 | $4.10 | ||||

| 1939 | $0.30 | $4.99 | ||||

| 1940 | $0.30 | $4.95 | ||||

| 1941 | $0.30 | $4.72 | ||||

| 1942 | $0.30 | $4.25 | ||||

| 1943 | $0.30 | $4.01 | ||||

| 1944 | $0.30 | $3.94 | ||||

| 1945 | $0.40 | $5.14 | ||||

| 1946 | $0.40 | $4.74 | ||||

| 1947 | $0.40 | $4.15 | ||||

| 1948 | $0.40 | $3.84 | $6.02 | |||

| 1949 | $0.40 | $3.89 | $6.11 | |||

| 1950 | $0.75 | $7.19 | $6.57 | |||

| 1951 | $0.75 | $6.62 | $6.76 | |||

| 1952 | $0.75 | $6.50 | $6.95 | |||

| 1953 | $0.75 | $6.45 | $7.19 | |||

| 1954 | $0.75 | $6.40 | $7.31 | |||

| 1955 | $0.75 | $6.42 | $7.60 | |||

| 1956 | $1.00 | $8.44 | $7.62 | |||

| 1957 | $1.00 | $8.17 | $7.82 | |||

| 1958 | $1.00 | $7.94 | $7.98 | |||

| 1959 | $1.00 | $7.89 | $8.29 | |||

| 1960 | $1.00 | $7.75 | $8.43 | |||

| 1961 | $1.15 | $8.83 | $8.69 | |||

| 1962 | $1.15 | $8.74 | $9.01 | |||

| 1963 | $1.25 | $9.38 | $9.33 | |||

| 1964 | $1.25 | $9.25 | $9.63 | |||

| 1965 | $1.25 | $9.11 | $9.93 | |||

| 1966 | $1.25 | $8.85 | $10.23 | |||

| 1967 | $1.40 | $9.69 | $10.35 | |||

| 1968 | $1.60 | $10.66 | $10.66 | |||

| 1969 | $1.60 | $10.20 | $10.70 | |||

| 1970 | $1.60 | $9.73 | $10.85 | |||

| 1971 | $1.60 | $9.33 | $11.26 | |||

| 1972 | $1.60 | $9.05 | $11.57 | |||

| 1973 | $1.60 | $8.52 | $11.85 | |||

| 1974 | $2.00 | $9.68 | $11.67 | |||

| 1975 | $2.10 | $9.39 | $11.92 | |||

| 1976 | $2.30 | $9.73 | $12.25 | |||

| 1977 | $2.30 | $9.14 | $12.39 | |||

| 1978 | $2.65 | $9.86 | $12.54 | |||

| 1979 | $2.90 | $9.86 | $12.53 | |||

| 1980 | $3.10 | $9.48 | $12.45 | |||

| 1981 | $3.35 | $9.36 | $12.67 | |||

| 1982 | $3.35 | $8.83 | $12.54 | |||

| 1983 | $3.35 | $8.46 | $12.91 | |||

| 1984 | $3.35 | $8.13 | $13.25 | |||

| 1985 | $3.35 | $7.86 | $13.46 | |||

| 1986 | $3.35 | $7.72 | $13.73 | |||

| 1987 | $3.35 | $7.46 | $13.77 | |||

| 1988 | $3.35 | $7.20 | $13.97 | |||

| 1989 | $3.35 | $6.90 | $14.09 | |||

| 1990 | $3.80 | $7.46 | $14.26 | |||

| 1991 | $4.25 | $8.05 | $14.36 | |||

| 1992 | $4.25 | $7.86 | $14.89 | |||

| 1993 | $4.25 | $7.66 | $14.95 | |||

| 1994 | $4.25 | $7.51 | $15.07 | |||

| 1995 | $4.25 | $7.33 | $15.14 | |||

| 1996 | $4.75 | $7.98 | $15.43 | |||

| 1997 | $5.15 | $8.47 | $15.70 | |||

| 1998 | $5.15 | $8.36 | $16.02 | |||

| 1999 | $5.65 | $8.98 | $16.46 | |||

| 2000 | $6.15 | $9.45 | $16.83 | |||

| 2001 | $6.15 | $9.19 | $17.08 | |||

| 2002 | $6.15 | $9.05 | $17.55 | |||

| 2003 | $6.15 | $8.84 | $18.13 | |||

| 2004 | $6.15 | $8.61 | $18.62 | |||

| 2005 | $6.15 | $8.33 | $18.98 | |||

| 2006 | $6.15 | $8.07 | $19.12 | |||

| 2007 | $6.65 | $8.48 | $19.25 | |||

| 2008 | $7.15 | $8.78 | $19.34 | |||

| 2009 | $7.25 | $8.94 | $19.79 | |||

| 2010 | $7.25 | $8.79 | $20.36 | |||

| 2011 | $7.25 | $8.52 | $20.36 | |||

| 2012 | $7.25 | $8.35 | $20.44 | |||

| 2013 | $7.25 | $8.23 | $20.52 | |||

| 2014 | $7.25 | $8.09 | $20.64 | |||

| 2015 | $7.75 | $8.63 | $20.85 | |||

| 2016 | $8.25 | $9.07 | $20.90 | |||

| 2017 | $8.25 | $8.88 | $21.10 | |||

| 2018 | $8.75 | $9.19 | $21.33 | |||

| 2019 | $8.75 | $9.03 | $21.57 | |||

| 2020 | $9.25 | $9.43 | $21.84 | |||

| 2021 | $9.25 | $9.25 | $9.25 | $9.25 | $22.29 | $22.29 |

| 2022 | $10.50 | $10.29 | $22.52 | |||

| 2023 | $11.50 | $11.02 | $22.87 | |||

| 2024 | $13.25 | $12.40 | $23.25 | |||

| 2025 | $15.00 | $13.72 | $23.69 |

Notes: Inflation measured using the CPI-U-RS and projected using the CBO's February 2021 projections for the CPI-U. Productivity is measured as total economy productivity net depreciation.

Sources: EPI analysis of the Fair Labor Standards Act and amendments, the Delaware minimum wage, and the proposed increase to $15 by 2025. Total economy productivity data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics Labor Productivity and Costs program. Average hourly wages of production nonsupervisory workers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Employment Statistics.

Beginning in 1999, Delaware lawmakers did step in to raise wages for the state’s lowest-paid workers, raising the state’s minimum wage modestly above the federal minimum for about a decade. The state reverted to the federal minimum from 2009 to 2014. Beginning in 2015, Delaware’s minimum wage was again raised above the federal minimum in stages until it reached the $9.25 value it has had since 2020. While this is certainly an improvement over federal policy, the state’s current minimum wage is still 13.2% lower than the minimum wage that applied in the late 1960s.

Allowing workers today to be paid less than their counterparts a generation ago makes no sense for the well-being of Delaware’s workforce or the state economy, and there is no economic justification for it. Over the past 50 years, the country has experienced enormous growth, and the economy’s capacity to deliver higher wages—through improvements in productivity—has more than doubled, growing by 109% since 1968. The top line in Figure A shows that, had the minimum wage kept pace with productivity growth since 1968, it would have reached $22.29 per hour by 2021, and would likely be nearly $24 by 2025.

Raising the Delaware minimum wage to $15 by 2025, as proposed in SB 15, would help correct policymakers’ failure to raise minimum wages more appropriately over the past five decades. Figure A shows that a minimum wage of $15 in 2025 would be the equivalent of $13.72 in today’s dollars, based on the Congressional Budget Office’s projections for inflation.2 This would finally grant Delaware’s low-wage workers a share of the country’s productivity gains over the past generation, with a wage 28% higher (adjusted for inflation) than the 1968 minimum wage. Again, it is important to recognize that since 1968, the economy’s capacity to deliver higher wages and living standards will have grown by 122% by 2025. Thus, raising the minimum wage 28% above the previous high point is meaningful, but it is still less than one-quarter of the economy’s productivity improvements of the past 50 years.

Summary of minimum wage increases under Delaware SB 15 and numbers of workers affected by the increases, 2022--2025

| Date | Minimum wage | Increase | Total estimated state workforce | Directly affected | Indirectly affected | Total affected | Affected workers’ share of state workforce |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 2021 | $9.25 | ||||||

| January 2022 | $10.50 | $1.25 | 436,000 | 27,000 | 23,000 | 50,000 | 11.5% |

| January 2023 | $11.50 | $1.00 | 437,000 | 43,000 | 19,000 | 63,000 | 14.3% |

| January 2024 | $13.25 | $1.75 | 439,000 | 61,000 | 41,000 | 102,000 | 23.2% |

| January 2025 | $15.00 | $1.75 | 441,000 | 92,000 | 30,000 | 122,000 | 27.8% |

Notes: Values reflect the result of the proposed change in the state minimum wage. Wage changes resulting from existing state and local minimum wage laws are accounted for by EPI’s Minimum Wage Simulation Model. Totals may not sum due to rounding. Shares calculated from unrounded values. Directly affected workers will see their wages rise as the new minimum wage rate exceeds their existing hourly pay. Indirectly affected workers have a wage rate just above the new minimum wage (between the new minimum wage and 115% of the new minimum). They will receive a raise as employer pay scales are adjusted upward to reflect the new minimum wage.

Source: Economic Policy Institute Wage Simulation Model; see David Cooper, Zane Mokhiber, and Ben Zipperer, Minimum Wage Simulation Model Technical Methodology, Economic Policy Institute, February 2019.

Effects on the Delaware workforce

In 2025, with the final increase to $15, SB 15 would raise the wages of an estimated 122,000 Delaware workers, or roughly 28% of the state’s wage-earning workforce. As shown in Table 1, this includes 92,000 workers who would be directly affected—meaning that they would otherwise be paid less than $15 in 2025—as well as 30,000 indirectly affected workers who would otherwise be earning just above $15. They are likely to receive a pay boost as employers raise wages to recruit and retain them under the new higher wage standard.

Wage impacts of raising the Delaware minimum wage to $15 by 2025

| All (directly & indirectly) affected workers | Directly affected workers only | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Minimum wage (nominal $) | Minimum wage (2021$) | Total wage increase (2021$) | Change in average hourly wage (2021$) | Change in avg. annual income (year-round workers) (2021$) | Real percent change in average annual income | Total wage increase (2021$) | Change in average hourly wage (2021$) | Change in avg. annual income (year-round workers) (2021$) | Real percent change in average annual income |

| March 2021 | $9.25 | $9.25 | ||||||||

| January 2022 | $10.50 | $10.29 | $28,768,000 | $0.41 | $600 | 3.8% | $20,746,000 | $0.62 | $900 | 6.4% |

| January 2023 | $11.50 | $11.02 | $61,308,000 | $0.71 | $1,100 | 6.3% | $55,021,000 | $0.98 | $1,400 | 9.5% |

| January 2024 | $13.25 | $12.40 | $167,145,000 | $1.13 | $1,800 | 8.8% | $148,983,000 | $1.80 | $2,800 | 16.3% |

| January 2025 | $15.00 | $13.72 | $313,678,000 | $1.72 | $2,800 | 12.8% | $297,094,000 | $2.24 | $3,600 | 18.4% |

Notes: Values reflect the result of the proposed change in the state minimum wage. Wage changes resulting from existing state and local minimum wage laws are accounted for by EPI’s Minimum Wage Simulation Model. Totals may not sum due to rounding. Shares calculated from unrounded values. Directly affected workers will see their wages rise as the new minimum wage rate exceeds their existing hourly pay. Indirectly affected workers have a wage rate just above the new minimum wage (between the new minimum wage and 115% of the new minimum). They will receive a raise as employer pay scales are adjusted upward to reflect the new minimum wage. Wage increase totals are cumulative of all preceding steps.

Source: Economic Policy Institute Wage Simulation Model; see David Cooper, Zane Mokhiber, and Ben Zipperer, Minimum Wage Simulation Model Technical Methodology, Economic Policy Institute, February 2019.

SB 15 would provide a substantial earnings boost to Delaware’s lowest-paid workers. As shown in Table 2, EPI’s model estimates that affected workers would receive a total of $314 million in additional wages through 2025. The average affected worker who works year round would see their real (inflation-adjusted) annual earnings rise by $2,800—a nearly 13% real pay increase. Among the directly affected workforce—i.e., those who would otherwise be paid less than $15—the policy change would lift pay by an average of 18% or about $3,600 in annual earnings for year-round workers. For someone making only $20,000 a year, that is a substantial increase in their spending power.

Demographic characteristics of workers who would be affected by increasing the Delaware minimum wage to $15 by 2025

| Group | Total estimated workforce | Directly affected | Share of group directly affected | Indirectly affected | Share of group indirectly affected | Total affected | Share of group who are affected | Group’s share of total affected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All workers | 440,500 | 92,000 | 21% | 30,400 | 7% | 122,400 | 28% | 100% |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Women | 223,900 | 54,600 | 24% | 16,500 | 7% | 71,100 | 32% | 58% |

| Men | 216,600 | 37,400 | 17% | 13,900 | 6% | 51,300 | 24% | 42% |

| Age | ||||||||

| Age 19 or younger | 22,400 | 16,300 | 73% | 1,500 | 7% | 17,700 | 79% | 14% |

| Age 20 or older | 418,200 | 75,800 | 18% | 28,900 | 7% | 104,700 | 25% | 86% |

| Ages 16–24 | 67,600 | 38,900 | 57% | 6,900 | 10% | 45,800 | 68% | 37% |

| Ages 25–39 | 137,400 | 27,100 | 20% | 10,900 | 8% | 38,000 | 28% | 31% |

| Ages 40–54 | 142,400 | 12,800 | 9% | 6,700 | 5% | 19,500 | 14% | 16% |

| Age 55 or older | 93,000 | 13,300 | 14% | 5,900 | 6% | 19,200 | 21% | 16% |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 279,500 | 43,400 | 16% | 16,400 | 6% | 59,800 | 21% | 49% |

| Black | 89,600 | 26,200 | 29% | 8,500 | 10% | 34,700 | 39% | 28% |

| Hispanic | 40,100 | 15,200 | 38% | 3,700 | 9% | 18,900 | 47% | 15% |

| AAPI | 21,500 | 3,900 | 18% | 400 | 2% | 4,300 | 20% | 4% |

| Other race/ethnicity | 9,800 | 3,400 | 34% | 1,300 | 13% | 4,700 | 48% | 4% |

| Not person of color | 279,500 | 43,400 | 16% | 16,400 | 6% | 59,800 | 21% | 49% |

| Person of color | 161,000 | 48,700 | 30% | 13,900 | 9% | 62,600 | 39% | 51% |

| Family status | ||||||||

| Married parent | 103,400 | 9,900 | 10% | 5,200 | 5% | 15,100 | 15% | 12% |

| Single parent | 42,700 | 12,800 | 30% | 4,200 | 10% | 16,900 | 40% | 14% |

| Married, no children | 119,300 | 11,800 | 10% | 6,400 | 5% | 18,200 | 15% | 15% |

| Unmarried, no children | 175,000 | 57,600 | 33% | 14,600 | 8% | 72,200 | 41% | 59% |

| Education | ||||||||

| Less than high school | 35,400 | 18,300 | 52% | 2,900 | 8% | 21,200 | 60% | 17% |

| High school | 120,900 | 36,500 | 30% | 12,600 | 10% | 49,200 | 41% | 40% |

| Some college, no degree | 93,100 | 27,700 | 30% | 8,400 | 9% | 36,100 | 39% | 29% |

| Associate degree | 35,700 | 5,400 | 15% | 3,000 | 8% | 8,400 | 23% | 7% |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 155,400 | 4,100 | 3% | 3,500 | 2% | 7,600 | 5% | 6% |

| Family income | ||||||||

| Less than $25,000 | 42,400 | 27,400 | 65% | 5,200 | 12% | 32,500 | 77% | 27% |

| $25,000–$49,999 | 73,400 | 17,700 | 24% | 9,700 | 13% | 27,400 | 37% | 22% |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 74,300 | 14,300 | 19% | 5,300 | 7% | 19,600 | 26% | 16% |

| $75,000–$99,999 | 65,900 | 10,100 | 15% | 3,600 | 5% | 13,700 | 21% | 11% |

| $100,000–$149,999 | 89,400 | 11,100 | 12% | 4,000 | 4% | 15,100 | 17% | 12% |

| $150,000 or more | 91,600 | 9,200 | 10% | 2,300 | 3% | 11,500 | 13% | 9% |

| Family income-to-poverty ratio | ||||||||

| At or below the poverty line | 26,300 | 18,900 | 72% | 2,600 | 10% | 21,500 | 82% | 18% |

| 100–199% poverty | 47,100 | 23,100 | 49% | 7,700 | 16% | 30,800 | 65% | 25% |

| 200–399% poverty | 127,800 | 27,000 | 21% | 11,600 | 9% | 38,500 | 30% | 31% |

| 400% or above | 239,300 | 23,100 | 10% | 8,500 | 4% | 31,600 | 13% | 26% |

| Work hours | ||||||||

| Part-time (<20 hours) | 42,200 | 20,500 | 49% | 3,300 | 8% | 23,900 | 57% | 20% |

| Mid-time (20–34 hours) | 62,200 | 31,100 | 50% | 6,400 | 10% | 37,500 | 60% | 31% |

| Full-time (35+ hours) | 336,100 | 40,400 | 12% | 20,600 | 6% | 61,100 | 18% | 50% |

| Industry | ||||||||

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing, hunting | 3,100 | 1,200 | 40% | 100 | 4% | 1,400 | 43% | 1% |

| Construction | 25,100 | 3,300 | 13% | 1,700 | 7% | 5,100 | 20% | 4% |

| Manufacturing | 37,200 | 4,600 | 12% | 2,100 | 6% | 6,600 | 18% | 5% |

| Wholesale trade | 8,300 | 1,100 | 14% | 800 | 10% | 1,900 | 23% | 2% |

| Retail trade | 54,600 | 23,400 | 43% | 6,100 | 11% | 29,500 | 54% | 24% |

| Transportation, warehousing, utilities | 19,600 | 2,500 | 13% | 1,200 | 6% | 3,700 | 19% | 3% |

| Information | 5,900 | 700 | 12% | 300 | 6% | 1,000 | 18% | 1% |

| Finance, insurance, real estate | 49,200 | 2,600 | 5% | 1,800 | 4% | 4,400 | 9% | 4% |

| Professional, scientific, management, technical services | 25,700 | 1,100 | 4% | 600 | 2% | 1,700 | 7% | 1% |

| Administrative, support, and waste management | 16,400 | 5,600 | 34% | 2,100 | 13% | 7,800 | 47% | 6% |

| Education | 46,100 | 4,300 | 9% | 2,300 | 5% | 6,500 | 14% | 5% |

| Health care | 68,900 | 12,500 | 18% | 5,500 | 8% | 18,000 | 26% | 15% |

| Arts, entertainment, recreational services | 9,100 | 4,100 | 45% | 700 | 8% | 4,800 | 53% | 4% |

| Accommodation | 3,300 | 1,500 | 45% | 500 | 14% | 1,900 | 58% | 2% |

| Restaurants and food service | 28,100 | 17,500 | 63% | 1,900 | 7% | 19,500 | 69% | 16% |

| Other services | 15,700 | 4,900 | 31% | 1,200 | 8% | 6,200 | 39% | 5% |

| Public administration | 24,300 | 1,000 | 4% | 1,300 | 5% | 2,300 | 9% | 2% |

Notes: Values reflect the population likely to be affected by the proposed changes in the Delaware minimum wage. Totals may not sum due to rounding. Shares calculated from unrounded values. Directly affected workers will see their wages rise as the new minimum wage rate will exceed their current hourly pay. Indirectly affected workers have a wage rate just above the new minimum wage (between the new minimum wage and 115% of the new minimum). They will receive a raise as employer pay scales are adjusted upward to reflect the new minimum wage. AAPI refers to Asian American/Pacific Islander.

Source: Economic Policy Institute Wage Simulation Model; see David Cooper, Zane Mokhiber, and Ben Zipperer, Minimum Wage Simulation Model Technical Methodology, Economic Policy Institute, February 2019.

Raising the Delaware minimum wage to $15 would also help combat gender and racial inequities, with disproportionate impacts on women and workers of color. As shown in Table 3, of the 122,000 workers likely to get a raise, 71,100 (58%) are women. Nearly one in three women workers (32%) in Delaware would get a raise from SB 15. Similarly, 51% of the affected workforce are people of color. In fact, nearly 40% of Black workers in Delaware would get a raise and almost half (47%) of Hispanic workers would get a raise.

Notably, a $15 minimum wage would primarily benefit adults in the prime career-building years, many of whom are supporting families. There is sometimes a perception that the workers who would benefit from a higher minimum wage are mostly teenagers in their first jobs. This is not true. In fact, the data show that most of the workers who would benefit from a $15 minimum wage are older and full-time workers. Table 3 shows that only 14% of affected workers in Delaware are teenagers while 63% are 25 years old or older. The average age of affected workers is 35 years old. Fifty percent of affected workers work 35 hours per week or more, and more than a quarter have children. In fact, raising the state minimum wage to $15 would provide a raise to 40% of all working single parents in Delaware.

Table 3 also shows that most workers who would receive a raise come from families with limited means. Nearly half (49%) of affected workers are in families with total annual incomes less than $50,000. For these families, every additional dollar they receive has a meaningful impact on their ability to make ends meet.

Using the federal government’s poverty guidelines, the data show that over 52,000 workers who would benefit from SB15 are either in poverty or close to it. In fact, raising the state minimum wage to $15 by 2025 would provide a raise to 82% of all working people in Delaware currently in poverty.

What the research shows about effects on employment

Whenever any minimum wage increase is proposed, concerns are always raised about the impact such a policy change might have on employment.3 By raising the cost of labor, do minimum wage increases cause businesses to employ significantly fewer workers, threatening the incomes of the low-wage workforce the measures are intended to help? This is one of the most heavily studied topics in economics, and the resounding conclusion of empirical research over the past several decades is a clear “no.” In a comprehensive review of nearly all published minimum wage research over the past 30 years, University of Massachusetts Amherst Professor Arindrajit Dube concludes that “the overall body of evidence suggests a rather muted effect of minimum wages to date on employment.”4 The median effect across studies in Dube’s review was that for every 10% increase in wages of low-wage workers, employment declined by 0.4%—essentially zero.

Importantly, even research on the highest minimum wages enacted at state or local levels has shown that there does not appear to be any sizable effect on jobs. In a paper published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, Doruk Cengiz and co-authors examined the effects of 138 state minimum wage changes that occurred in the United States between 1979 and 2014.5 They found that even with minimum wages rising as high as 55% of the median wage—roughly the same as is being proposed for Delaware—there was no evidence of any reduction in the total number of jobs for low-wage workers. Harvard and U.C. Berkeley researchers Ellora Derenoncourt and Claire Montialoux demonstrated that highest national minimum wage we’ve had—in 1968, the equivalent of $10.66 per hour in 2021 dollars—also raised wages and significantly reduced Black–white earnings inequality without employment losses.6 Using data from low-wage counties, where minimum wage increases have raised labor costs much more than in high-wage labor markets, U.C. Berkeley researchers Anna Godøy and Michael Reich found that the policies significantly reduced poverty and had essentially no employment impact.7 And in a paper just recently published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, Arindrajit Dube and Attila Lindner found that 21 city-level minimum wage increases raised wages in those cities with little effect on the number of low-wage jobs.8

Effects on businesses and the broader economy

There are several reasons why higher minimum wages have never meaningfully manifested the negative job impacts predicted by textbook models. Research has shown that when minimum wages are raised, businesses are typically able to adjust through variety of channels.9 These include:

- reductions in turnover and increased job tenure, which can reduce business costs of recruitment, hiring, and training;

- increases in productivity, as a result of increased work effort by employees, raised expectations by managers, or new efficiencies identified by businesses;

- wage compression—i.e., raises for higher-paid workers may be delayed or reduced;

- increased consumer demand, generated by the increased spending power of low-wage workers across the affected region; and

- modest price increases, on the scale of 0.4–1.1% per 10% increase in the minimum wage.10 These increases can be more easily absorbed as a result of concurrent boost in pay to a large portion of the region’s workforce, combined with the fact that all area businesses will be facing similar increases in labor costs—i.e., no single business will be at a competitive disadvantage if they all must raise prices.

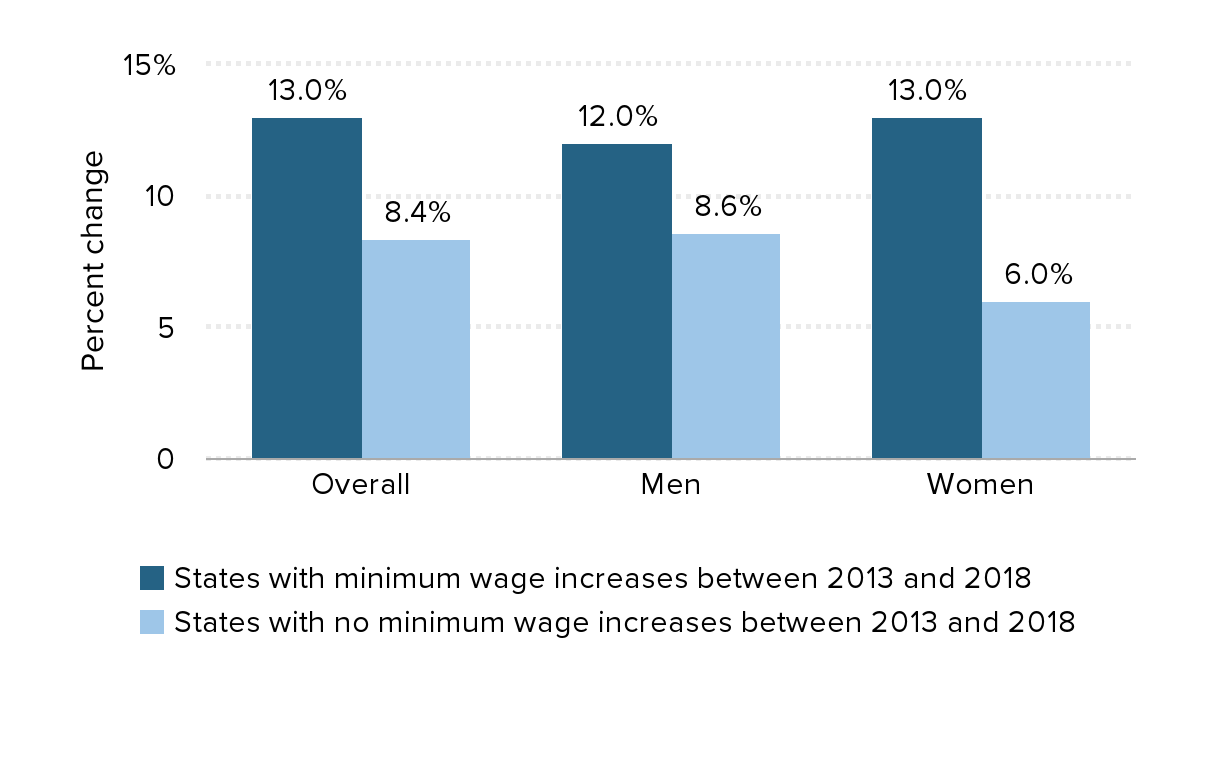

Research by my colleague Elise Gould has shown that in recent years, as numerous states have enacted higher minimum wages, there has been a clear pattern of low-wage workers in those states seeing faster wage growth than their counterparts in states that did not raise their minimum wages.11 Figure B shows that in the states that raised their minimum wage between 2013 and 2018, wages among low-wage workers grew 5 percentage points faster than in states that did not change their minimum wage. Among low-wage women workers, these effects were even more pronounced: Wage growth was twice as strong for women at the bottom of the wage scale in states that raised their minimum wages versus in states that did not.

Wage growth at the bottom was strongest in states with minimum wage increases between 2013 and 2018: 10th-percentile wage growth from 2013 to 2018, by presence of state minimum wage increase between 2013 and 2018 and by gender

| States with minimum wage increases between 2013 and 2018 | States with no minimum wage increases between 2013 and 2018 | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 13.0% | 8.4% |

| Men | 12.0% | 8.6% |

| Women | 13.0% | 6.0% |

Notes: Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, the District of Columbia, Florida, Hawaii, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Vermont, Washington, and West Virginia increased their minimum wages at some point between 2013 and 2018. Sample based on all workers ages 16 and older.

Source: EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata from the U.S. Census Bureau

Too often discussions on the minimum wage focus narrowly on these questions of potential employment effects, but this is a deeply flawed way of evaluating the merits of the policy. Research has shown that—regardless of any employment effects—higher minimum wages have led to clear, sizable welfare improvements for workers, their families, and their communities that far outweigh any potential costs of the policy. For example, in an article published in the American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, Arindrajit Dube demonstrates that the income-boosting effects of higher minimum wages significantly reduces the number of families below the poverty line.12 Similarly, Kevin Rinz and John Voorheis—researchers at the U.S. Census Bureau—have shown that not only do higher minimum wages lead to increases in income for low-income families, but that those income gains actually accelerate in the years after the minimum wage is raised.13 Higher minimum wages have been shown to reduce rates of smoking and are associated with a slate of other improved measures of public health.14 Researchers at Rutgers University and Clemson University also find that higher minimum wages reduce recidivism and may reduce property crimes.15 This policy has been shown to achieve broad public good that should not be overlooked or obscured by claims by opponents that raising the minimum wage would lead to economic devastation that has never manifest with any previous minimum wage increase.

Why now is a good time to enact this policy change

The COVID-19 pandemic has been devasting for workers, families, and businesses throughout the country, and recovering from the pandemic’s harm—both economic and otherwise—will take time. Fortunately, raising the minimum wage is a good way to heal some of the economic harm and expedite the recovery.

The immediate benefits of a minimum wage increase are in the earnings boost for the lowest-paid workers—increases in spending power that also deliver broader benefits to the economy. Extra dollars in the pockets of working families throughout the state would help by boosting aggregate demand. Economists generally recognize that low-wage workers are more likely than any other income group to spend any extra earnings immediately on previously unaffordable basic needs or services. Indeed, researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston find that minimum wage increases are associated with higher consumer spending, particularly in places with higher concentrations of low-wage workers.16

With vaccinations accelerating and a possible end to the pandemic in sight, it is an ideal time to inject more money into the pockets of workers and families who will go out and quickly spend those dollars. The best way for businesses throughout Delaware and the rest of the country to recover from the pandemic is by bolstering strong consumer demand.

A higher minimum wage would also more appropriately compensate many of the workers who have shouldered tremendous risk throughout the pandemic. EPI’s research on the effects of a federal $15 minimum wage by 2025 shows that the majority of workers who would benefit are essential or front-line workers.17 Because the composition of workers who would benefit in Delaware is similar to the national estimates, it’s safe to assume that essential and front-line workers likely constitute the majority of those who would benefit in Delaware. During the COVID-19 pandemic, these workers have kept the economy running at great risk to their health and their families, and very few of them have received hazard pay to compensate for their now-more-dangerous work. Raising their pay through a minimum wage hike is a good way to recognize the critical roles they have in the economic health of every community.

Conclusion

Given improvements in productivity, low-wage workers in Delaware and throughout the United States could be earning significantly higher wages today had lawmakers made different choices over the past 50 years. As such, the question for policymakers today should not be whether we can have significantly higher minimum wages, but rather, in what time frame we can achieve such levels.

Raising the Delaware minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2025 would finally raise the state’s wage floor to a purchasing power above the previous high point set in the late 1960s. It would raise pay for over 122,000 workers in the state, with particular benefit for women and workers of color. It would also more appropriately reward the essential and front-line workers who have kept the economy going during the pandemic, and would bolster consumer spending as the state and country recover.

Research has shown that past minimum wage increases have achieved their intended effects, raising pay for low-wage workers with little to no negative impact on employment. Moreover, research that has looked beyond the narrow question of employment impacts has found clear, meaningful benefits from higher minimum wages to low-wage workers, their families, and their broader communities.

I strongly encourage the committee and the full Delaware legislature to pass SB 15 and help strengthen the future for Delaware’s lowest-paid workers, their families, and their communities.

Notes

1. Inflation adjustment uses the Consumer Price Index for all Urban Consumers, Research Series (CPI-U-RS). See Bureau of Labor Statistics, “CPI Research Series Using Current Methods,” updated March 2021.

2. Projected inflation is from the CPI-U series published by the Congressional Budget Office. See Congressional Budget Office, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2021 to 2031, “10-Year Economic Projections” (downloadable Excel file supplement), February 2021.

3. See National Employment Law Project, Consider the Source: 100 Years of Broken-Record Opposition to the Minimum Wage, March 2013.

4. Arindrajit Dube, Impacts of Minimum Wages: Review of the International Evidence, report prepared for Her Majesty’s Treasury (UK), November 2019.

5. Doruk Cengiz et al., “The Effect of Minimum Wages on Low-Wage Jobs,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 134, no. 3 (2019).

6. Ellora Derenoncourt and Claire Montialoux, “Minimum Wages and Racial Inequality,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 136, no. 1 (February 2021).

7. Anna Godøy and Michael Reich, “Are Minimum Wage Effects Greater in Low-Wage Areas?” Industrial Relations, January 2021.

8. Arindrajit Dube and Attila Lindner, “City Limits: What Do Local-Area Minimum Wages Do?,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 35, no. 1 (2021).

9. For greater detail, see John Schmitt, Why Does the Minimum Wage Have No Discernible Effect on Employment?, Center for Economic and Policy Research Briefing Paper, February 2013.

10. See Sylvia Allegretto and Michael Reich, “Are Local Minimum Wages Absorbed by Price Increases? Estimates from Internet-Based Restaurant Menus,” ILR Review 71, no. 1 (January 2018): 35–63.

11. Elise Gould, State of Working America 2018: Wage Inequality Marches On—and Is Even Threatening Data Reliability, Economic Policy Institute, February 2019.

12. Arindrajit Dube, “Minimum Wages and the Distribution of Family Incomes,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 11, no. 4 (2019): 268–304.

13. Kevin Rinz and John Voorheis, “The Distributional Effects of Minimum Wages: Evidence from Linked Survey and Administrative Data,” Working Paper 2018-02, Center for Administrative Records Research and Applications, U.S. Census Bureau, March 2018.

14. J. Paul Leigh, Wesley Leigh, and Juan Du, “Minimum Wages and Public Health: A Literature Review,” February 27, 2018.

15. Amanda Agan and Michael Makowsky, “The Minimum Wage, EITC, and Criminal Recidivism,” September 25, 2018.

16. Daniel Cooper, María José Luengo-Prado, and Jonathan A. Parker, “The Local Aggregate Effects of Minimum Wage Increases,” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 52 (December 2019): 5–35.

17. David Cooper, Zane Mokhiber, and Ben Zipperer, Raising the Federal Minimum Wage to $15 by 2025 Would Lift the Pay of 32 Million Workers, Economic Policy Institute, March 2021.