EPI Economist Heidi Shierholz testified before the Joint Economic Committee of the U.S. Congress at a hearing on “Empowerment in the Workplace” on June 18, 2014.

Good afternoon Chairman Brady, Vice Chair Klobuchar, and other distinguished members of the committee. My name is Heidi Shierholz, and I am a labor market economist at the Economic Policy Institute in Washington, D.C. I appreciate the opportunity to appear before you today to discuss the topic of empowerment in the workplace.

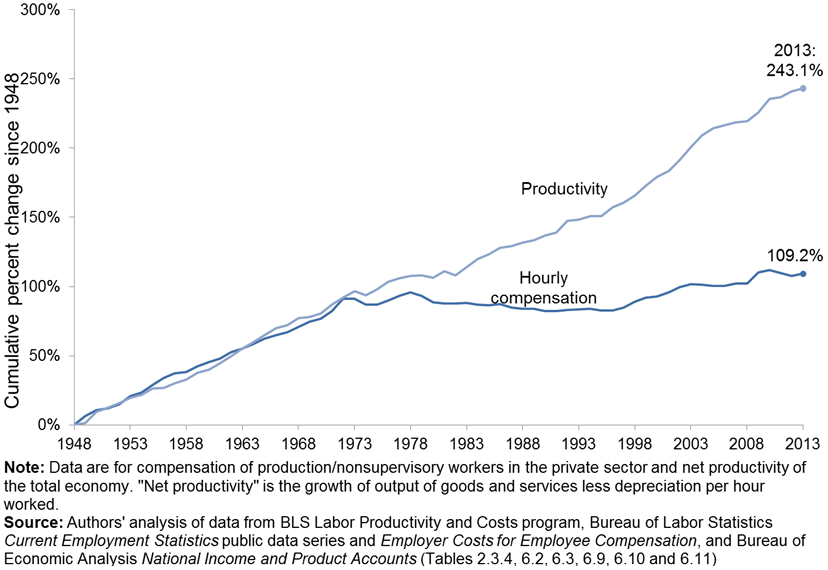

It is perhaps useful to start by defining what is meant by an “empowered workforce.” Under any reasonable definition, an empowered workforce is one that shares fairly in the fruits of its labor. This means that the mark of empowerment can be seen in the data on productivity—how much economic output workers produce on average in an hour of work—and compensation. In particular, a minimal definition of an empowered workforce is a workforce where, as productivity grows, most workers share in those gains and see compensation growth. By contrast, an economy where productivity grows but the fruits of that growth accrue to just a small sliver of workers is an economy where that small share is empowered, but where the workforce overall is broadly disempowered.

From the late 1940s to the mid-1970s, the U.S. had an empowered workforce by this definition. Figure A shows productivity growth along with growth in hourly compensation for private-sector production and nonsupervisory workers, who comprise slightly more than 80 percent of private-sector payroll employment. From the late 1940s to the mid-1970s, as productivity grew, compensation grew with it in lock step. Since the 1970s, however, the U.S. has not met that minimal definition of an empowered workforce. Productivity continued to rise consistently, but the typical worker’s compensation began lagging further and further behind.

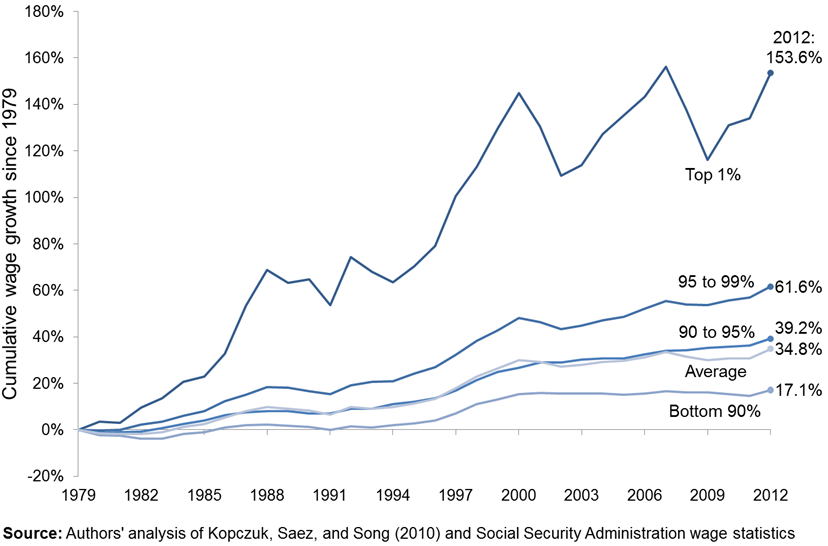

Rising wage inequality is at the core of the disconnect between productivity growth and compensation growth for most workers since the 1970s. As Figure B shows, between 1979 and 2012, wages grew by 35 percent on average. But that average growth masked enormous variation by wage level. The top 1 percent saw their wages grow by more than 150 percent over this period. The bottom 90 percent of the wage distribution, on the other hand, saw growth of 17 percent—about half of the overall average growth rate. In other words, the top captured so much of the growth over this period that the entire bottom 90 percent saw wage growth that was lower than average. Workers were more productive, but the fruits of that productivity growth were not going to most workers; they were instead accruing to a small share of high-wage earners. The fact that the entire bottom 90 percent of the wage distribution saw below-average wage growth over the last 35 years means that a discussion about workplace empowerment—or, for the last 35 years, the lack thereof—boils down in a very real sense to a discussion of rising wage inequality.

Knowing what is behind rising wage inequality and the disempowerment of the workforce is crucial to knowing what steps policymakers can take to reverse it. I am very pleased that the committee is focusing this hearing on labor market practices and policies, which are a key—but often overlooked—part of this dynamic. I will briefly mention several policies in this area that could help ensure fair pay and stronger benefits for workers:

- A higher minimum wage. In inflation-adjusted terms, the minimum wage is now more than 25 percent below its peak in 1968, despite a low-wage workforce that is much older and more educated. In the 1950s and 1960s, a period of a broadly empowered workforce, the minimum wage grew in tandem with productivity growth. If the minimum wage had grown at just one-fourth the speed of productivity growth since then, it would now be over $12.00. The Harkin-Miller proposal to raise the minimum wage to $10.10 by 2016 would provide a crucial boost to this eroded labor standard.

- A higher overtime salary threshold. The real value of the salary threshold under which all salaried workers, regardless of their work duties, are covered by overtime provisions has been allowed to erode dramatically. Simply adjusting the threshold for inflation since 1975 would raise it to $984 per week, from its current level of $455, guaranteeing additional millions of workers time-and-a-half pay when they work more than 40 hours in a week.

- Combat “just-in-time” schedules. Low-wage service workers are increasingly subject to employers’ “just-in-time” scheduling practices, an enormously disempowering practice where employers give workers little advance notice of their schedules, call workers into work during nonscheduled times to meet unexpected customer demand, and send workers home early when business is slow. Policymakers should pass laws that require minimum guaranteed hours per pay period and require compensation for a minimum number of hours when workers are called into or sent home from work unexpectedly.

- Update labor law. Labor law has not kept pace with dramatically increased employer aggressiveness in fighting unions, which has resulted in a growing wedge between workers’ desire to organize and bargain collectively and their ability to do so. Research shows that deunionization can explain about a third of the entire growth of wage inequality among men from 1973 to 2007 and around a fifth of the growth among women (Mishel 2012). The section of the National Labor Relations Act that authorized “right-to-work” laws should be repealed, significant penalties should be legislated for unfair labor practice violations, and the National Labor Relations Board should make its election process more efficient by eliminating wasteful waiting periods (Eisenbrey 2014).

- Crack down on “wage theft.” Wage theft is when employers do not pay workers for the work they have done, a practice rampant in the low-wage labor market. Employers steal billions of dollars from their employees each year by working them off the clock, failing to pay the minimum wage, and by not paying the overtime pay they have a right to receive. Survey research shows that well over two-thirds of low-wage workers have been the victims of wage theft, but the government resources to help them recover their lost wages are scant and largely ineffective (Bernhardt et al. 2009).

- Crack down on misclassification. Misclassification is when employers treat employees as independent contractors, which allows them to avoid paying workers compensation, unemployment insurance, the minimum wage, or offering overtime, which in turn means workers are denied access to these benefits and protections (Eisenbrey 2014).

- Mandatory paid leave policies. Congress should enact a right to paid sick days. Two out of five private-sector workers are so disempowered that they lack the right to even a single day of paid sick leave (BLS 2013).

- Equal pay for equal work/pay transparency. Congress should pass the Paycheck Fairness Act, which would institute worker-empowering changes to the Equal Pay Act of 1963, including prohibiting retaliation against workers who inquire about their employers’ wage practices or disclose their own wages.

Again I’d like to thank the committee for highlighting how labor market policies have affected worker empowerment. There is a strong public narrative that dismisses rising wage inequality and worker disempowerment as simply a natural and unstoppable consequence of a modern economy. But as I’ve shown, there are government policies at the root of rising wage inequality and worker disempowerment. That’s actually good news, because it means that the dramatic rise in inequality that has impeded worker empowerment for a generation does not have to continue—it has been driven by many policy choices that can be changed. We need to enforce the labor standards we have, update the ones that need it, and empower workers to bargain for better working conditions for themselves and their families. For more information on this, please see a recent paper I coauthored, Raising America’s Pay: Why It’s Our Central Economic Policy Challenge (Bivens et al. 2014).

References

Bernhardt, Annette, Ruth Milkman, Nik Theodore, Douglas D. Heckathorn, Mirabai Auer, and James DeFilippis. 2009. Broken Laws, Unprotected Workers: Violations of Employment and Labor Laws in America’s Cities. National Employment and Law Project. http://www.nelp.org/page/-/brokenlaws/BrokenLawsReport2009.pdf?nocdn=1

Bureau of Labor Statistics (U.S. Department of Labor) National Compensation Survey– Employee Benefits in the United States. 2013. Employee Benefits in the United States [March economic news release]. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/ebs2.pdf

Bivens, Josh, Elise Gould, Lawrence Mishel, and Heidi Shierholz. 2014. Raising America’s Pay: Why It’s Our Central Economic Policy Challenge. Economic Policy Institute, Briefing Paper No. 378. http://www.epi.org/publication/raising-americas-pay/

Eisenbrey, Ross. 2014. Improving the Quality of Jobs Through Better Labor Standards. Path to Full Employment. http://www.pathtofullemployment.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/eisenbrey.pdf

Mishel, Lawrence. 2012. Unions, Inequality, and Faltering Middle-Class Wages. Economic Policy Institute, Issue Brief No. 342. http://www.epi.org/publication/ib342-unions-inequality-faltering-middle-class/

U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee (JEP). 2010. Expanding Access to Paid Sick Leave: The Impact of the Healthy Families Act on America’s Workers. http://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm?a=Files.Serve&File_id=abf8aca7-6b94-4152-b720-2d8d04b81ed6

Western, Bruce, and Jake Rosenfeld. 2011. Unions, Norms, and the Rise in American Wage Inequality. Harvard University. http://www.wjh.harvard.edu/soc/faculty/western/pdfs/Unions_Norms_and_Wage_Inequality.pdf