Full Report

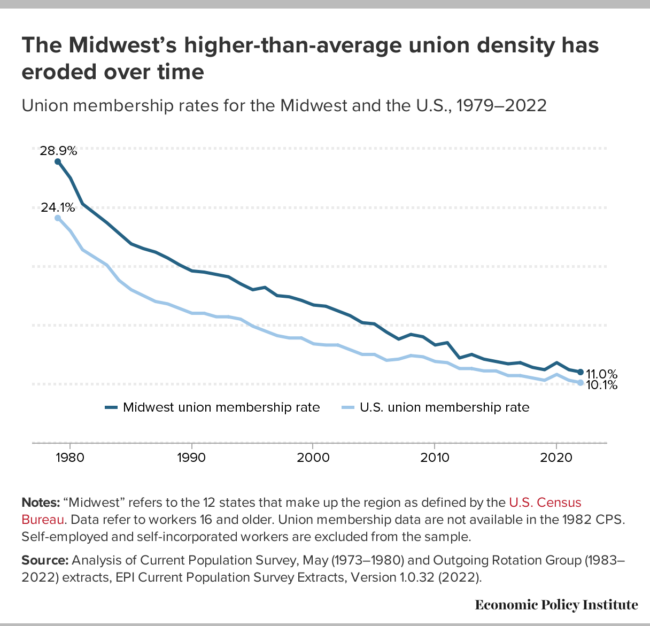

From the end of World War II until the mid-1980s, the Midwest enjoyed relatively low inequality and high worker wages, in large part due to high rates of union membership. The Midwest led the country as a region ripe with high-quality union jobs and pathways into the middle class. Yet this leadership has been challenged by years of relentless attacks on unions, deindustrialization, and the failures of policymakers to prioritize working families’ economic security. In the wake of the Great Recession, austerity—at the federal level and in virtually every state—only exacerbated these dynamics. As a result, the Midwest has endured years of slow wage growth, slow job growth, public-sector employment shortfalls, and declines in unionization.

The federal government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic was different. By providing strong fiscal relief at the scale of the problem, federal lawmakers protected the country from a protracted recession and provided regional policymakers with the resources to make transformative investments in support of working families.

Policies impacting workers

Jobs and unemployment

- Figure A. Difference between pre-recession employment projections and actual employment in May 2023

- Figure B. Unemployment rate by race

- Table 2. Unemployment rate by region and Midwestern state

- Appendix Figure A. Unemployment rate by region and for the U.S.

Employment

- Figure C. Prime-age employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) by region

- Figure D. Prime-age EPOP by Midwestern state

- Figure E. Prime-age EPOP in the Midwest by race/ethnicity

- Figure F. Prime-age EPOP in the Midwest by gender

- Figure G. Prime-age EPOP in the Midwest by race and gender

Employment by industry

- Figure H. Midwest private-sector employment change since business cycle peak, Jan. 2008 and Feb. 2020

- Figure I. Employment change in the five largest Midwest industries, Feb. 2020–May 2023

- Figure J. Employment change since Jan. 2008 and Feb. 2020 business cycle peaks, select Midwest industries

- Figure K. Public-sector employment loss, Midwestern states and U.S., Feb. 2020–May 2023

- Appendix Table 1. Midwest employment by industry, Feb. 2020 and May 2023

Wages

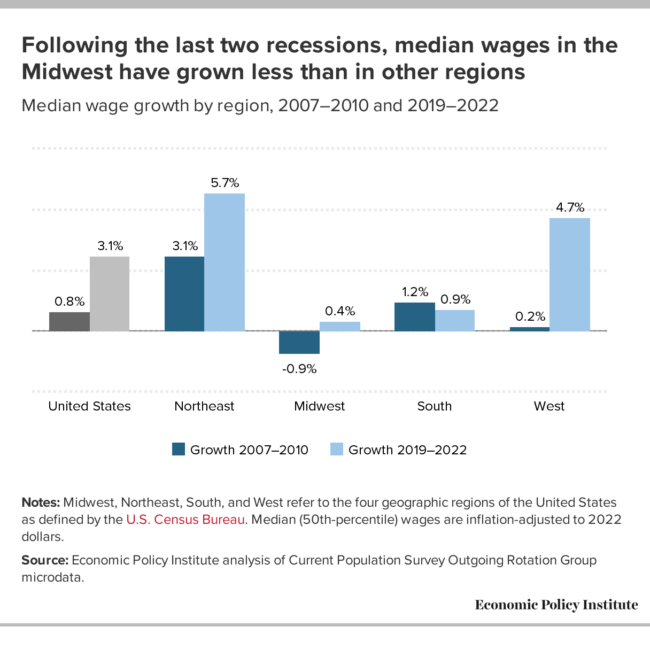

- Figure L. Median wage growth by region

- Figure M. Median hourly wages by region

- Figure N. Relative median wage by region

- Figure O. Median wage growth by Midwestern state

- Figure P. Real wage changes at the 10th percentile in the Midwest

- Figure Q. 10th-percentile hourly wages by region

- Figure R. Share of workers earning less than $15 an hour by region

- Figure S. Share of workers earning less than $15 an hour in Midwestern states

- Appendix Table 2. Real median wages in Midwestern states and the U.S.

Safety net and worker protections

- Figure T. Paid sick leave access by region

Poverty

- Figure U. Official poverty rate, U.S. and Midwest, 2007–2021

- Table 3. Three-year-average official poverty rates between 2005 and 2021, U.S. and Midwestern states

- Table 4. Supplemental and official poverty rates by state, 2019–2021 average

Unionization

However, as federal government relief efforts wind down, Midwestern policymakers must take full advantage of an improving economy and new federal resources made possible through recent legislation. They can use these resources to bolster public systems (e.g., education, health care) and rebuild the structures and programs that will create high-quality union jobs in infrastructure, manufacturing, and clean energy technologies.

The Midwest’s story as a place of opportunity for workers building the core products of the U.S. economy need not be lost to the past. Regional lawmakers have a historic opportunity to restore that character, advancing equity and economic opportunity for all who call the region home.

Key findings

- The Midwest has seen an increase in anti-worker policies. Most Midwestern states have implemented policies in the past 15 years that have worsened job quality and reduced economic security for working families, such as limiting worker rights and preempting local governments’ efforts to improve labor standards.

- Racial employment gaps persist. The Midwest remains the region with the nation’s lowest unemployment and highest employment-to-population ratio, but racial employment gaps remain significant.

- The Midwest has failed to recover lost public-sector jobs. As in the rest of the country, regional job growth exiting the pandemic has been strong, yet the Midwest’s public sector has still not recovered the jobs lost at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Wage growth is slow. A significant bright spot of the current recovery nationally and in the Midwest has been the largely unprecedented improvement in wages for the economy’s lowest-paid workers. However, the state of typical worker wages in the Midwest is less encouraging. The Midwest has had the slowest wage growth of any region in the country both during the Great Recession and since the beginning of the pandemic. Between 2019 and 2022, real median wages increased only $0.08 (0.4%) in the Midwest, while the Northeast and West saw increases of more than a dollar (5.7% and 4.7%, respectively). Between 1979 and 2022, the Midwest’s relative median wage—the ratio of the regional median wage to the national median wage—has declined more than any other region’s.

- Union density has declined. Union density has declined in the Midwest more than in any other region since 1979. Declining union density is a contributor to the region’s slow wage growth and growth in inequality. Once a union-dense region, the Midwest today has only one state that ranks in the top 10 for union membership.

- Midwesterners lack access to paid leave. The region lags the rest of the country in the share of private-sector workers with access to paid sick leave as an employee benefit. The Midwest has also been slower than other regions to pass legislation guaranteeing paid sick days to all workers.

- A strong policy response reduced poverty during the pandemic. A weak policy response in the wake of the Great Recession exacerbated poverty, but the strong policy response to the pandemic recession led to a significant drop in poverty rates (as captured by the supplemental poverty measure) in the Midwest and nationwide. Unfortunately, the sunsetting of pandemic relief programs means poverty rates have returned to their previous levels.

- The federal pandemic response shows these trends can be reversed. The federal government’s response to the pandemic demonstrates that, going forward, state policymakers have the opportunity to enact policies that will increase job quality and build racial equity.

Midwestern policymakers have an opportunity to change course to improve the lives of working families in the region

This report closely examines the economy of the Midwest as the nation recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic. The influx of federal funds from the CARES Act, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), and other federal legislation blunted the worst economic effects from COVID, but those supports are now waning. Policymakers across the Midwest have choices to make, choices that will critically shape the economic trajectory for working families in the region going forward.

Midwestern policymakers enacted numerous anti-worker policies in the wake of the Great Recession

The 12 states of the Midwest region1 faced just such a moment of decision over a decade ago. The Midwest entered the Great Recession as a region with (on the whole) high workforce participation, strong public- and private-sector unions, and many dynamic local governments that were supporting strong labor standards and safe workplaces (Pabst 2011; McKinney 2021; Wolfe et al. 2021).

In the wake of the Great Recession, though, right-wing politicians took control in all Midwestern states except Illinois and Minnesota (Tope, Pickett, and Chiricos 2015) and began passing policies that had negative outcomes for workers, especially for Black and brown workers. The majority of Midwestern states embraced fiscal austerity, disinvested in public services, and rolled back workers’ rights. Further, they restricted local governments from (among other things) raising minimum wages, enacting paid leave, or setting high-road labor standards for publicly funded development projects. The predictable outcomes were an increase in inequality, wage stagnation, and worsening racial wage and employment gaps.

Table 1 notes some of the key policy decisions Midwestern states made from the Great Recession through the beginnings of the COVID-19 pandemic.

State policy changes impacting workers in Midwestern states, 2009–2022

| Anti-worker policy changes | Worker-friendly policy changes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Passed RTW law | Limited public-sector collective bargaining rights | Preempted local pro-worker laws | Increased state minimum wage | Expanded Medicaid | Expanded collective bargaining rights |

| Illinois | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Indiana | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Iowa | * | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Kansas | * | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Michigan | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Minnesota | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Missouri | ↩ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Nebraska | * | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| North Dakota | * | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Ohio | ↩ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| South Dakota | * | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Wisconsin | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

Notes: “Passed RTW law” means the state enacted a so-called right-to-work law. South Dakota adopted Medicaid expansion in 2022, but it was not implemented until mid-2023.

✓ = adopted policy 2009–2022

* = already had policy prior to 2009

↩ = Legislation passed by legislators but overturned by a ballot measure

Sources: Sherer, Why ‘Right-to-Work’ Was Always Wrong for Michigan (EPI, 2023); Morrissey and Sherer, Unions Can Reduce the Public-Sector Pay Gap (EPI, 2022); Wolfe et al., Preempting Progress in the Heartland (EPI, 2021); Economic Policy Institute, Current Population Survey Extracts (2023); Kaiser Family Foundation, Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions: Interactive Map (2023); Sherer, Illinois Workers’ Rights Amendment Sets New Bar for State Worker Power Policy (EPI, 2022).

Anti-worker policy changes

RTW laws. So-called right-to-work (RTW) laws limit the power of private-sector unions. RTW laws have been shown to exacerbate income inequality, lower worker wages, and widen racial wage and employment gaps (Sherer 2023).

Five Midwestern states already had RTW laws on the books before the Great Recession; in the 2010s, Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin joined them. Missouri also enacted RTW in 2017, but Missouri’s voters overturned that decision in a 2018 ballot measure, with 67% of those voting opposed to RTW (Missouri Secretary of State 2018).

Restrictions on public-sector unions. In addition, eight Midwestern states passed legislation limiting the rights of public employees to organize and collectively bargain. The first of these was passed in a once pro-union state. In 1959, Wisconsin was the first state to grant public employees the right to collectively bargain (Lichtenstein 2002). The passage of Act 10 in March 2011 undermined those rights.

Wisconsin’s Act 10 prohibited negotiations over most workplace issues (such as hours of work, employee discipline, health insurance, and safety) and limited unions’ rights to collect union dues through payroll deduction. It also forced all unions to annually hold a recertification vote to maintain their status as a collective bargaining representative. The law further prevented public employers and unions from agreeing to worker raises above the Consumer Price Index without subjecting it to a voter referendum. The law’s clear purpose was to limit the power of workers, and it resulted in a significant decline in union membership in the state.

Preemption. A third policy enacted by most Midwestern state legislatures was the preemption of local labor standards. Preemption refers to state laws restricting the right of local governments (mostly cities and counties) to enact local ordinances on certain issues. Three particular local government actions were targeted by these preemption laws, which prohibited cities and counties from:

- Setting a minimum wage higher than that of the state. In Kansas City, Missouri, and Milwaukee, Wisconsin, preemption laws forced a reduction in the cities’ existing minimum wages.

- Enacting paid leave requirements for employers receiving public money.

- Setting standards for municipal contracts and procurement through mechanisms common elsewhere such as project labor agreements (PLA)—contracts used in the construction industry to set basic conditions for safety, pay, and benefits on municipal projects—and prevailing wage laws.

Worker-friendly policy changes

Minimum wage increases. There is strong evidence that higher minimum wages are an effective policy for raising the pay of low-wage workers (EPI 2023b). Six of the 12 Midwestern states passed laws to raise their minimum wages during this period. However, the minimum wage in five Midwestern states is still set at the federal level of $7.25.

Medicaid expansion. Medicaid expansion reduces a state’s uninsured rate (Guerra-Cardus and Lukens 2023) and is associated with lower mortality rates, especially among women and Black people (Lee, Dodge, and Terrault 2022). Ten Midwestern states have expanded Medicaid through the Affordable Care Act; two have not (KFF 2023).

Expansion of collective bargaining rights. Two states in the Midwest—Minnesota and Illinois—took steps during this period to strengthen workers’ rights. Minnesota banned noncompete clauses and captive audience meetings, among other measures, and Illinois enshrined collective bargaining rights in the state’s constitution.

Midwestern states should pursue pro-worker policies to build on post-pandemic progress

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the region’s economy was bolstered by significant investment from the federal government. This investment—through the CARES Act, the American Rescue Plan Act, and other legislation—provided relief at the scale of the problem.

When millions of jobs were lost in the initial months of the pandemic, most of the unemployed and their families were reasonably protected. Indeed, pandemic safety net programs kept millions out of poverty (Banerjee and Zipperer 2022). Supports for businesses and fiscal aid to state and local governments prevented more severe layoffs. With household income reasonably maintained by federal programs, strong consumer demand fueled a rapid recovery, with employers eager to rehire staff. This tight labor market gave low-wage workers leverage, leading to strong real wage growth for most workers and a job market that had largely recovered by the end of 2022.

Midwestern states now have an opportunity to build on this momentum and shift away from the policy choices that weakened worker power prior to the pandemic. Going back to the anti-union, anti-worker austerity of the 2010s will exacerbate inequality, suppress wages, and weaken public services. That is not the path the Midwest should take. Instead, the Midwest should take the high road. Policies to support collective bargaining, strengthen labor standards, and invest in public services will lead to better lives for working families across the region.

Subsequent sections of this report describe how the Midwest economy has performed coming out of the pandemic, and how that performance compares both with the period leading up to the outbreak of COVID-19 and with the period of economic recovery following the Great Recession. We first look at the recovery of jobs and at trends in unemployment rates and employment levels. Next, we look at wages and other measures of job quality. We then discuss poverty and inequality in the region. We close with a discussion of the role of unions and collective bargaining in strengthening job quality and the lives of working families.

Jobs and unemployment

The Midwest continues to face job deficits relative to other regions

As of May 2023, the Midwest has gained 151,700 jobs (+0.5%) since February 2020—the second-smallest gain of any region. The Northeast gained less than 3,000 jobs (+0.01%), while the South gained over 2.5 million jobs (+4.6%) and the West gained nearly 1.1 million jobs (+3.0%) (Economic Policy Institute analysis of BLS-CES various years).

While the raw numbers seem to imply the Midwest is doing better than the Northeast, the Midwest is in fact the only region facing a jobs deficit—the gap between the current level of jobs and the level of jobs expected under pre-recession employment rates when accounting for population growth. The region would need to add about 116,000 jobs to regain its February 2020 employment at its May 2023 population size.

Meanwhile, all other regions have added more jobs than we would expect had they not experienced a recession. The West has added almost 330,000 jobs above this counterfactual (employment levels if the pandemic recession had not occurred), while the South has added over 188,000 jobs and the Northeast has added almost 38,000 (see Figure A).

The Midwest is the only region facing a jobs deficit relative to pre-pandemic employment trends: Difference between pre-recession employment projections and actual employment in May 2023

| Region | Difference between actual employment and pre-pandemic projections |

|---|---|

| Midwest | -115,648 |

| South | 188,481 |

| Northeast | 37,811 |

| West | 327,605 |

Notes: Midwest, Northeast, South, and West refer to the four geographic regions of the United States as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau. Job deficit and surplus calculations are based on an estimation of the number of jobs that would exist if pre-pandemic employment levels were maintained under the current population size in each region (counterfactual employment). The deficit (or surplus) is the difference between counterfactual employment and the actual number of jobs in each region in May 2023.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Employment Statistics and Bureau of Labor Statistics Local Area Unemployment Statistics.

The Midwest’s unemployment rate is at a historic low, but racial disparities remain a concern

As a result of federal action to promote a strong jobs recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic recession, by 2022 all regions had achieved near-full or full recoveries to 2019 unemployment rates. The Midwest was no exception.

The region has enjoyed comparatively low unemployment rates over the medium term: The Midwest’s unemployment rate has been lower than the U.S. average for the past 13 years and has been the lowest of any region for seven of those years (see Appendix Figure A). As of May 2023, the Midwest’s unemployment rate—3.2%—was once again lower than any other region’s and has reached a historic low for the region (FRED 2023).

Within Midwestern states, unemployment remained highest in Illinois (4.1%) and Michigan (3.7%) as of May 2023. As shown in Table 2, all other Midwestern states had unemployment rates below the national average of 3.7% (BLS-LAUS various years).

The Midwest’s unemployment rate is the lowest of any region: Unemployment rate by region and Midwestern state, select months

| February 2020 | May 2023 | |

|---|---|---|

| United States | 3.5% | 3.7% |

| West | 4.0% | 4.0% |

| South | 3.5% | 3.3% |

| Northeast | 3.9% | 3.6% |

| Midwest | 3.6% | 3.2% |

| Illinois | 3.8% | 4.1% |

| Indiana | 3.4% | 3.1% |

| Iowa | 2.6% | 2.7% |

| Kansas | 3.1% | 2.9% |

| Michigan | 3.8% | 3.7% |

| Minnesota | 3.9% | 2.9% |

| Missouri | 3.3% | 2.5% |

| Nebraska | 3.0% | 1.9% |

| North Dakota | 2.2% | 2.1% |

| Ohio | 4.6% | 3.6% |

| South Dakota | 2.6% | 1.9% |

| Wisconsin | 3.0% | 2.4% |

Note: Midwest, Northeast, South, and West refer to the four geographic regions of the United States as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Local Area Unemployment Statistics data.

Workers of all races and ethnicities fared better during the current economic recovery than after the Great Recession. Over the first three years of the post–Great Recession recovery (2007–2010), the unemployment rate increased by over 6 points for Black, Hispanic, and AAPI/AIAN/multiracial workers2 and nearly 4 points for white workers in the Midwest (see Figure B). After the Great Recession, these unemployment rates did not return to pre-recession rates until 2015—eight years later.

The Midwest’s unemployment rate has recovered relatively quickly following the pandemic recession, but racial disparities remain: Unemployment rate by race in the Midwest, 2007–2022

| Year | Black | Hispanic | White | AAPI / AIAN / multiracial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 11.5% | 6.3% | 4.4% | 10.2% |

| 2008 | 13.4% | 7.6% | 5.1% | 11.3% |

| 2009 | 18.4% | 12.8% | 8.4% | 15.5% |

| 2010 | 18.6% | 12.4% | 8.2% | 17.2% |

| 2011 | 18.2% | 11.0% | 7.1% | 18.6% |

| 2012 | 15.9% | 9.5% | 6.2% | 13.6% |

| 2013 | 15.5% | 10.5% | 6.0% | 13.6% |

| 2014 | 14.0% | 7.7% | 4.7% | 13.2% |

| 2015 | 11.1% | 6.4% | 3.9% | 10.4% |

| 2016 | 10.6% | 5.9% | 3.8% | 12.2% |

| 2017 | 8.8% | 5.3% | 3.4% | 8.2% |

| 2018 | 7.2% | 4.4% | 3.2% | 6.6% |

| 2019 | 7.2% | 4.2% | 3.0% | 8.4% |

| 2020 | 14.0% | 10.7% | 6.3% | 12.8% |

| 2021 | 10.1% | 5.6% | 3.8% | 9.1% |

| 2022 | 7.2% | 4.5% | 2.8% | 7.6% |

| 2023 |

Notes: “Midwest” refers to the 12 states that make up the region as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau. AAPI stands for Asian American and Pacific Islander, and AIAN stands for American Indian and Alaska Native.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey microdata from the U.S. Census Bureau.

In contrast, between 2019, the year just prior to the pandemic, and 2022, the unemployment rate declined among white workers (0.2 percentage points) and AAPI/AIAN/multiracial workers (0.8 percentage points). The unemployment rate for Black workers stayed the same. Among Hispanic workers, it increased 0.3 points.

Throughout this period, though, severe disparities have persisted. The unemployment rate for Black workers and AAPI/AIAN/multiracial workers was more than 2.5 times the white unemployment rate in 2022. Reducing these disparities requires bold investments, including expanding workers’ rights and worker power, investing in the care economy and public sector, addressing the affordable housing crisis, and reducing barriers to employment for formerly incarcerated Midwesterners (Kamper 2022a).

Employment

The Midwest achieved a quick return to pre-pandemic employment and must resist austerity to sustain progress

Arguably the best measure of labor market health, the prime-age employment-to-population ratio or prime-age “EPOP” is the share of workers ages 25–54 who are currently employed. Whereas other measures—such as the unemployment rate and the labor force participation rate—can mask labor market weakness resulting from workers’ decisions to seek work or be skewed by demographic changes, the prime-age EPOP is a straightforward calculation of what share of the core working-age population has a job.

The Midwest is a region that works. As shown in Figure C, since the mid-1980s, the Midwest has consistently had the highest employment-to-population ratio of any region of the country, reaching a peak of 84.3% in 1999.

However, failure to restore the public sector in the wake of the Great Recession in most states has stalled employment growth, and racial and gender employment gaps persist. The post-2000 decline in the prime-age EPOP nationwide was a result of fiscal austerity, which sapped aggregate demand (spending by households, businesses, and governments) and prevented a full recovery of employment (Bivens 2014). In the Midwest, harmful trade policy exacerbated these dynamics by further reducing aggregate demand (Shields and Stettner 2020).

Fortunately, fiscal stimulus in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic has quickened the recovery of the prime-age EPOP relative to the early aughts.

Figure C shows that despite the unprecedented job losses caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, in both the Midwest and other regions, the prime-age EPOP recovered significantly faster after the pandemic-induced recession than it did following the Great Recession. In the Midwest, the prime-age EPOP took 11 years following the Great Recession to recover to its 2007 levels, and all regions exhibited similar trends. In contrast, in all regions, the prime-age EPOP has nearly recovered to its 2019 rates within three years. In 2022, the Midwest prime-age EPOP of 82% remains the highest in the country (see Figure C). Nationwide, the June 2023 prime-age EPOP rate—80.9%—is approaching the all-time high of 81.9% reached in April 2000 (Irwin 2023).

The federal response during the pandemic hastened the region’s employment recovery. However, without policies to support high-road jobs, the Midwest risks further decline in job quality, weakening workforce participation, and continued growth in inequality.

Employment has recovered to pre-pandemic rates in all regions but is consistently highest in the Midwest: Prime-age employment-to-population ratio by region, 1979–2022

| United States | Northeast | Midwest | South | West | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 74.7% | 73.0% | 75.4% | 74.8% | 75.4% |

| 1980 | 74.3% | 73.1% | 74.1% | 74.7% | 75.3% |

| 1981 | 74.7% | 73.7% | 74.7% | 75.1% | 75.3% |

| 1982 | 73.6% | 73.1% | 73.1% | 73.8% | 74.3% |

| 1983 | 73.8% | 73.3% | 73.5% | 74.0% | 74.3% |

| 1984 | 75.9% | 75.3% | 75.7% | 76.3% | 76.1% |

| 1985 | 76.7% | 76.3% | 76.5% | 77.1% | 76.9% |

| 1986 | 77.4% | 77.6% | 77.7% | 76.9% | 77.4% |

| 1987 | 78.4% | 78.8% | 78.8% | 78.0% | 78.2% |

| 1988 | 79.2% | 79.2% | 79.9% | 78.7% | 79.2% |

| 1989 | 79.9% | 79.7% | 80.9% | 79.4% | 79.8% |

| 1990 | 79.7% | 79.3% | 80.9% | 79.4% | 79.1% |

| 1991 | 78.6% | 77.7% | 80.3% | 78.6% | 77.8% |

| 1992 | 78.3% | 76.9% | 80.7% | 78.3% | 77.0% |

| 1993 | 78.6% | 77.5% | 81.0% | 78.6% | 76.9% |

| 1994 | 79.3% | 77.6% | 82.0% | 79.2% | 77.9% |

| 1995 | 79.8% | 78.2% | 82.9% | 79.6% | 78.2% |

| 1996 | 80.2% | 79.3% | 83.2% | 79.9% | 78.4% |

| 1997 | 80.9% | 80.1% | 83.9% | 80.3% | 79.3% |

| 1998 | 81.1% | 80.5% | 83.9% | 80.6% | 79.5% |

| 1999 | 81.4% | 80.9% | 84.3% | 81.0% | 79.7% |

| 2000 | 81.5% | 80.9% | 83.8% | 81.1% | 80.1% |

| 2001 | 80.5% | 80.2% | 82.9% | 79.9% | 79.4% |

| 2002 | 79.3% | 79.5% | 81.6% | 78.5% | 78.1% |

| 2003 | 78.8% | 78.8% | 81.0% | 78.2% | 77.6% |

| 2004 | 79.0% | 79.2% | 80.8% | 78.3% | 78.1% |

| 2005 | 79.3% | 79.4% | 81.1% | 78.9% | 78.4% |

| 2006 | 79.8% | 79.8% | 81.6% | 79.1% | 79.3% |

| 2007 | 79.9% | 79.9% | 81.4% | 79.3% | 79.5% |

| 2008 | 79.1% | 79.8% | 80.5% | 78.3% | 78.4% |

| 2009 | 75.8% | 77.0% | 77.0% | 75.1% | 74.8% |

| 2010 | 75.1% | 76.4% | 76.7% | 74.5% | 73.6% |

| 2011 | 75.1% | 76.0% | 77.1% | 74.6% | 73.5% |

| 2012 | 75.7% | 76.1% | 77.9% | 75.3% | 74.1% |

| 2013 | 75.9% | 76.4% | 78.0% | 75.1% | 74.8% |

| 2014 | 76.7% | 76.9% | 79.5% | 75.8% | 75.4% |

| 2015 | 77.2% | 78.0% | 80.3% | 76.0% | 76.0% |

| 2016 | 77.9% | 78.5% | 80.8% | 76.8% | 76.9% |

| 2017 | 78.6% | 79.3% | 80.9% | 77.6% | 77.8% |

| 2018 | 79.4% | 80.3% | 81.6% | 78.3% | 78.5% |

| 2019 | 80.0% | 80.7% | 82.0% | 79.0% | 79.3% |

| 2020 | 75.6% | 75.6% | 78.4% | 75.2% | 74.0% |

| 2021 | 77.6% | 77.7% | 80.0% | 77.0% | 76.4% |

| 2022 | 79.9% | 80.6% | 81.9% | 78.9% | 79.2% |

Notes: Midwest, Northeast, South, and West refer to the four geographic regions of the United States as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau. The prime-age employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) is the share of people ages 25–54 who are working.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey microdata from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Though the prime-age EPOP varies widely across states, all Midwestern states’ prime-age EPOPs recovered faster after the pandemic than after the Great Recession

Within the Midwest, the prime-age EPOP varies widely across different states but has exhibited similar trends since 2007. The prime-age EPOP is consistently highest in North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa, Nebraska, and Minnesota, and lowest in Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois.

In all Midwestern states, the prime-age EPOP fell during the Great Recession and faced an uneven recovery over the subsequent decade. During the pandemic recession, the prime-age EPOP fell more quickly and recovered more quickly than during the Great Recession, following a v-shaped pattern in most states.

Compared with 2007, the year prior to the Great Recession, and 2019, the year prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, four states exhibit prime-age EPOPs that are higher in 2022 than in both key previous years: Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, and Iowa. However, the other eight Midwestern states are faring worse on prime-age EPOP in 2022 relative to at least one of those years—or relative to both, as is the case in Ohio and Wisconsin. Wisconsin’s 2022 prime-age EPOP lags furthest behind 2007 levels, followed by slightly smaller gaps in Ohio, North Dakota, and South Dakota. South Dakota’s prime-age EPOP increased over its 2019 rate more than any other Midwestern state; the opposite is true for Wisconsin (see Figure D).

In seven Midwestern states, the prime-age EPOP has surpassed 2019 rates, while Ohio and Wisconsin trail their 2007 rates: Prime-age employment-to-population ratio by Midwestern state, select years

| 2007 | 2019 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 79.9% | 80.0% | 79.9% |

| Michigan | 76.0% | 79.5% | 77.6% |

| Ohio | 80.9% | 80.2% | 80.1% |

| Indiana | 79.9% | 80.3% | 81.3% |

| Illinois | 80.6% | 80.8% | 81.7% |

| Wisconsin | 85.1% | 85.2% | 82.3% |

| Missouri | 81.8% | 82.0% | 83.1% |

| Kansas | 84.1% | 83.6% | 84.0% |

| Minnesota | 85.5% | 85.8% | 85.8% |

| Nebraska | 85.8% | 86.6% | 86.4% |

| Iowa | 86.0% | 86.5% | 86.9% |

| North Dakota | 87.7% | 85.7% | 87.0% |

| South Dakota | 88.0% | 85.2% | 87.6% |

Note: The prime-age employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) is the share of people ages 25–54 who are working.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey microdata from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Employment disparities by race and gender persist and, in some cases, have grown

Despite high employment rates overall and progress for Black workers, disparities remain in employment based on race/ethnicity and gender.

Employment rates by race/ethnicity

While the gaps between the white EPOP and the AAPI, Hispanic, and Black EPOPs have narrowed over the last 15 years, significant gaps remain, and the prime-age EPOP gap between white workers and AIAN/multiracial/other workers has grown (see Figure E). The Black prime-age EPOP (76.4% in 2022) is 7.1 percentage points lower than the white rate of 83.5%. The AIAN/multiracial/other prime-age EPOP (68.0%) is 15.5 points lower than the white rate.

The prime-age EPOP among white, Hispanic, and AIAN/multiracial/other workers has not recovered to 2019 levels. However, the prime-age EPOP among Black and AAPI workers has exceeded 2019 levels by 1.3 percentage points and 3.9 percentage points, respectively.

The recovery of the Black prime-age EPOP is an especially positive development given long-standing race-based disparities in labor market outcomes. The Black prime-age EPOP faced a slow recovery after the Great Recession but has reached an all-time high in the current recovery. This is likely the result of a tight labor market spurred by policy investments during the pandemic recession.

The Black-white prime-age EPOP gap has narrowed but Indigenous-white gap has widened: Prime-age employment-to-population ratio in the Midwest, by race/ethnicity, 2007–2022

| White | Black | Hispanic | AAPI | AIAN / multiracial / other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 83.2% | 72.0% | 77.5% | 77.2% | 72.5% |

| 2008 | 82.3% | 69.6% | 77.3% | 79.0% | 70.0% |

| 2009 | 79.3% | 63.5% | 71.9% | 79.6% | 64.8% |

| 2010 | 78.9% | 63.9% | 72.6% | 72.5% | 66.2% |

| 2011 | 79.6% | 62.9% | 72.9% | 74.2% | 61.8% |

| 2012 | 80.3% | 64.7% | 74.7% | 76.0% | 62.8% |

| 2013 | 80.4% | 65.9% | 74.0% | 75.4% | 64.6% |

| 2014 | 81.7% | 69.1% | 76.2% | 74.6% | 65.4% |

| 2015 | 82.5% | 70.3% | 77.2% | 76.0% | 64.9% |

| 2016 | 83.0% | 71.4% | 77.4% | 76.1% | 63.7% |

| 2017 | 83.0% | 71.5% | 78.6% | 78.4% | 65.4% |

| 2018 | 83.7% | 74.0% | 77.5% | 77.6% | 69.3% |

| 2019 | 83.9% | 75.1% | 79.0% | 78.5% | 68.7% |

| 2020 | 81.1% | 67.3% | 73.6% | 75.8% | 64.0% |

| 2021 | 82.2% | 70.3% | 77.3% | 79.0% | 64.7% |

| 2022 | 83.5% | 76.4% | 78.2% | 82.4% | 68.0% |

Notes: “Midwest” refers to the 12 states that make up the region as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau. AAPI stands for Asian American and Pacific Islander, AIAN stands for American Indian and Alaska Native, and other is other race.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey microdata from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Employment rates by gender

Little progress has been made to close the gap between the prime-age men’s and prime-age women’s rates of employment. The share of prime-age men in the Midwest with a job has consistently been at least 10 percentage points higher than that of women in the Midwest since 2007 (see Figure F).

A key reason for the gender gap in employment is our nation’s care economy crisis. Women bear the brunt of caregiving responsibilities, both paid and unpaid, both for children and other family members (Gould, Sawo, and Banerjee 2021). The lack of accessible and affordable care forces women to make impossible choices between unpaid care work at home and underpaid work in the formal economy. Investments in the care economy would create opportunities for high-quality jobs in care work and enable unpaid caregivers to enter the labor force.

Little progress has been made to close the large gender employment gap: Prime-age employment-to-population ratio in the Midwest by gender, 2007–2022

| Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 87.3% | 75.6% |

| 2008 | 85.8% | 75.2% |

| 2009 | 80.9% | 73.2% |

| 2010 | 81.0% | 72.4% |

| 2011 | 82.0% | 72.2% |

| 2012 | 83.4% | 72.5% |

| 2013 | 83.5% | 72.7% |

| 2014 | 84.9% | 74.3% |

| 2015 | 85.9% | 74.8% |

| 2016 | 86.3% | 75.4% |

| 2017 | 86.2% | 75.9% |

| 2018 | 87.0% | 76.3% |

| 2019 | 87.2% | 76.9% |

| 2020 | 83.1% | 73.7% |

| 2021 | 85.0% | 75.0% |

| 2022 | 87.1% | 76.8% |

Notes: “Midwest” refers to the 12 states that make up the region as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau. The prime-age employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) is the share of people ages 25–54 who are working.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey microdata from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Employment rates at the intersection of race/ethnicity and gender

When considering the intersection of race and gender on prime-age employment in the Midwest, there is a clear clustering of white, Hispanic, and AAPI prime-age men exhibiting high EPOP rates (88%–90% in 2022), as seen in Figure G. Meanwhile, AIAN, multiracial, and other race/ethnicity men and women—as well as Black, Hispanic, and AAPI prime-age women—are employed at much lower rates (65%–75%). The prime-age EPOP for white women falls in between these two clusters (79%). While the prime-age EPOP for Black men has historically been low relative to white women, Black men’s prime-age EPOP in 2022 was equal to that of white women.

The intersection of gender and race/ethnicity disparities in caregiving work plays a role in the low prime-age EPOP rates among AAPI, Black, and Hispanic women. Women of all race/ethnicity groups spend more time providing unpaid care work at home, with Hispanic women spending the most time caregiving across all demographic groups (Gallagher, Robbins, and Mason 2023).

The prime-age EPOP is high among white, Hispanic, and AAPI men but low for multiracial workers and Hispanic women: Prime-age employment-to-population ratio in the Midwest by race and gender, select years

| Race/ethnicity and gender combination | 2007 | 2010 | 2019 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAPI men | 89.2% | 83.6% | 89.3% | 89.6% |

| Hispanic men | 89.0% | 81.0% | 88.6% | 89.0% |

| White men | 88.8% | 83.0% | 88.7% | 88.1% |

| Black men | 73.5% | 63.9% | 76.5% | 78.8% |

| White women | 77.6% | 74.8% | 79.1% | 78.8% |

| AAPI women | 66.0% | 62.5% | 68.2% | 75.8% |

| Black women | 70.8% | 64.0% | 73.8% | 74.2% |

| AIAN / multiracial / other men | 78.1% | 68.9% | 74.5% | 71.5% |

| Hispanic women | 63.9% | 61.7% | 68.5% | 66.9% |

| AIAN / multiracial / other women | 65.8% | 63.8% | 63.3% | 64.5% |

Notes: “Midwest” refers to the 12 states that make up the region as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau. The prime-age employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) is the share of people ages 25–54 who are working. AAPI stands for Asian American and Pacific Islander, AIAN stands for American Indian and Alaska Native, and other is other race.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey microdata from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Employment by industry

The employment recovery has been successful overall but varies by industry, and state and local government shortfalls persist

The pandemic’s initial effects on Midwest employment varied dramatically across different industries. As was the case nationwide, industries that involved face-to-face interactions—restaurants, retail, travel—were hit particularly hard. From February to April 2020, Midwest employment in leisure and hospitality was nearly cut in half (-48.9%)—a drop that was second only to the Northeast. Notably, Midwest employment losses over the same period in government and manufacturing were larger than in any other region, with losses of nearly 7% and 15%, respectively (Economic Policy Institute analysis of BLS-CES various years).

That said, throughout the country, total nonfarm employment (which includes most public- and private-sector workers) has recovered much faster in the current recovery than after the Great Recession. In the lead-up to the Great Recession, Midwest nonfarm employment peaked in January 2008 and did not return to that level until November 2014—81 months (nearly seven years) later (see Figure H). In contrast, before the pandemic recession, nonfarm employment peaked in February 2020, declined sharply, and recovered to pre-pandemic levels by February 2023—a span of 35 months, or just shy of three years. Federal pandemic relief, including loans to businesses to hire employees and stimulus payments to households that allowed workers to return to the labor market, strongly curtailed the Midwest’s period of low employment and created the conditions necessary for a quick recovery.

Federal fiscal relief at the scale of the problem led to a faster recovery from the pandemic recession: Midwest private-sector employment change since business cycle peak, January 2008 and February 2020

| 2008 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0.999736 | 0.992438 |

| 2 | 0.997298 | 0.850449 |

| 3 | 0.996439 | 0.869385 |

| 4 | 0.995977 | 0.903073 |

| 5 | 0.995395 | 0.91974 |

| 6 | 0.99296 | 0.929511 |

| 7 | 0.991627 | 0.934906 |

| 8 | 0.989758 | 0.941797 |

| 9 | 0.985996 | 0.940636 |

| 10 | 0.981225 | 0.938 |

| 11 | 0.975792 | 0.943654 |

| 12 | 0.965997 | 0.946007 |

| 13 | 0.96165 | 0.950777 |

| 14 | 0.955435 | 0.951821 |

| 15 | 0.948417 | 0.952471 |

| 16 | 0.945832 | 0.955125 |

| 17 | 0.941173 | 0.962834 |

| 18 | 0.938037 | 0.962205 |

| 19 | 0.9371 | 0.960734 |

| 20 | 0.936235 | 0.964095 |

| 21 | 0.935697 | 0.967339 |

| 22 | 0.935505 | 0.970071 |

| 23 | 0.934602 | 0.975981 |

| 24 | 0.934385 | 0.980528 |

| 25 | 0.934332 | 0.98252 |

| 26 | 0.935081 | 0.984563 |

| 27 | 0.938031 | 0.985628 |

| 28 | 0.940349 | 0.98667 |

| 29 | 0.939774 | 0.991611 |

| 30 | 0.939667 | 0.992742 |

| 31 | 0.940261 | 0.994009 |

| 32 | 0.940132 | 0.994872 |

| 33 | 0.943794 | 0.996822 |

| 34 | 0.944042 | 0.996362 |

| 35 | 0.944394 | 0.999353 |

| 36 | 0.94598 | 1.000954 |

| 37 | 0.946467 | |

| 38 | 0.948213 | |

| 39 | 0.950692 | |

| 40 | 0.950877 | |

| 41 | 0.95032 | |

| 42 | 0.953614 | |

| 43 | 0.954708 | |

| 44 | 0.956828 | |

| 45 | 0.956753 | |

| 46 | 0.957825 | |

| 47 | 0.959143 | |

| 48 | 0.961701 | |

| 49 | 0.963525 | |

| 50 | 0.966671 | |

| 51 | 0.966859 | |

| 52 | 0.967023 | |

| 53 | 0.96786 | |

| 54 | 0.967407 | |

| 55 | 0.968514 | |

| 56 | 0.970584 | |

| 57 | 0.97136 | |

| 58 | 0.972455 | |

| 59 | 0.973443 | |

| 60 | 0.974563 | |

| 61 | 0.977214 | |

| 62 | 0.977425 | |

| 63 | 0.975987 | |

| 64 | 0.978397 | |

| 65 | 0.979592 | |

| 66 | 0.97957 | |

| 67 | 0.982187 | |

| 68 | 0.983917 | |

| 69 | 0.984735 | |

| 70 | 0.986279 | |

| 71 | 0.987119 | |

| 72 | 0.986534 | |

| 73 | 0.988308 | |

| 74 | 0.989312 | |

| 75 | 0.991023 | |

| 76 | 0.993646 | |

| 77 | 0.995143 | |

| 78 | 0.995074 | |

| 79 | 0.99688 | |

| 80 | 0.997471 | |

| 81 | 0.999015 | |

| 82 | 1.00128 |

Note: “Midwest” refers to the 12 states that make up the region as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Employment Statistics data.

The Midwest’s two largest industries by shares of overall employment are trade, transportation, and utilities and education and health. The five largest Midwest industries are listed in Figure I. (See Appendix Table 1 for employment levels in all industries in the Midwest.)

While total nonfarm employment in the region has now surpassed its pre-recession peak, not all industries have regained the jobs they lost. As shown in Figure I, state and local government faces a deficit of over 2.2% (nearly 100,000 jobs). Education and health faces a smaller but still substantial deficit of 0.3% (15,300 jobs). Trade, transportation, and utilities and professional business services have recovered (and exceeded) their pre-recession employment levels in the Midwest.

Smaller Midwest industries include construction, financial services, and leisure and hospitality. Construction has grown 5.0% since February 2020—the largest increase of any Midwest industry—and financial services has grown 0.6%. Meanwhile, leisure and hospitality remains 2.7% below February 2020 employment (Economic Policy Institute analysis of BLS-CES various years).

While the pandemic recovery has been uneven across industries, it has nevertheless been much faster than the recovery from the Great Recession. Figure J demonstrates this for three specific industries—manufacturing, leisure and hospitality, and state and local government. For example, after the pre–Great Recession business cycle peak, manufacturing still had not recovered 144 months later. After the pre-pandemic business cycle peak, manufacturing recovered within a span of 29 months.

The Midwest’s public sector faces large employment deficits compared with pre-pandemic levels: Employment change (in thousands) in the five largest Midwest industries, February 2020–May 2023

| Industry | Employment change in thousands (% change) |

|---|---|

| State and local government | -98 |

| Government (local, state, federal) | -89.7 |

| Education and health | -15.3 |

| Professional business services | 118.6 |

| Trade, transportation, and utilities | 158.3 |

Notes: “Midwest” refers to the 12 states that make up the region as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau. Employment deficits are calculated by subtracting February 2020 employment from May 2023 employment.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Employment Statistics data.

While overall employment recovered faster after the pandemic economic recession, not all industries have recovered evenly

: Employment change since January 2008 business cycle peak, select Midwest industries

| Manufacturing | Leisure & hospitality | State & local govt. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0.999535 | 0.998566 | 1.000615 |

| 2 | 0.991716 | 0.994946 | 1.000114 |

| 3 | 0.987759 | 0.99621 | 1.00155 |

| 4 | 0.984664 | 0.996722 | 1.002575 |

| 5 | 0.9862 | 0.995117 | 1.003122 |

| 6 | 0.97389 | 0.991771 | 1.003418 |

| 7 | 0.969003 | 0.991088 | 1.004831 |

| 8 | 0.965396 | 0.989312 | 1.006586 |

| 9 | 0.957647 | 0.987263 | 1.004649 |

| 10 | 0.947826 | 0.983575 | 1.006335 |

| 11 | 0.932933 | 0.982141 | 1.004854 |

| 12 | 0.899446 | 0.974799 | 1.005948 |

| 13 | 0.889509 | 0.971999 | 1.005629 |

| 14 | 0.874244 | 0.968482 | 1.005218 |

| 15 | 0.856907 | 0.96435 | 1.00335 |

| 16 | 0.837196 | 0.968243 | 1.006814 |

| 17 | 0.824095 | 0.964282 | 1.004991 |

| 18 | 0.821628 | 0.962199 | 1.001185 |

| 19 | 0.823885 | 0.960082 | 1.000182 |

| 20 | 0.824374 | 0.961004 | 0.998519 |

| 21 | 0.823164 | 0.956257 | 1.001117 |

| 22 | 0.821163 | 0.954004 | 1.000205 |

| 23 | 0.821093 | 0.953184 | 0.998997 |

| 24 | 0.821163 | 0.952296 | 0.999066 |

| 25 | 0.821512 | 0.952501 | 0.997767 |

| 26 | 0.822745 | 0.950828 | 0.996582 |

| 27 | 0.827539 | 0.955677 | 0.995967 |

| 28 | 0.83089 | 0.953867 | 0.993141 |

| 29 | 0.831797 | 0.954072 | 0.992503 |

| 30 | 0.836684 | 0.95636 | 0.985142 |

| 31 | 0.835358 | 0.958204 | 0.988469 |

| 32 | 0.839128 | 0.959672 | 0.986077 |

| 33 | 0.841501 | 0.96196 | 0.987808 |

| 34 | 0.842083 | 0.96237 | 0.986897 |

| 35 | 0.84455 | 0.961926 | 0.984755 |

| 36 | 0.847668 | 0.960355 | 0.98594 |

| 37 | 0.84967 | 0.959604 | 0.983342 |

| 38 | 0.853067 | 0.96237 | 0.983296 |

| 39 | 0.857605 | 0.964555 | 0.984527 |

| 40 | 0.859187 | 0.964077 | 0.982841 |

| 41 | 0.859816 | 0.964521 | 0.980676 |

| 42 | 0.86454 | 0.968038 | 0.980129 |

| 43 | 0.864516 | 0.972375 | 0.979514 |

| 44 | 0.866238 | 0.97357 | 0.979536 |

| 45 | 0.868193 | 0.973604 | 0.977531 |

| 46 | 0.869264 | 0.976404 | 0.976893 |

| 47 | 0.872266 | 0.975175 | 0.976939 |

| 48 | 0.875361 | 0.98057 | 0.977941 |

| 49 | 0.877618 | 0.985556 | 0.978306 |

| 50 | 0.881062 | 0.992112 | 0.980744 |

| 51 | 0.882435 | 0.991975 | 0.980608 |

| 52 | 0.884087 | 0.988936 | 0.982932 |

| 53 | 0.886438 | 0.992863 | 0.97924 |

| 54 | 0.890277 | 0.993 | 0.971948 |

| 55 | 0.887624 | 0.995834 | 0.976506 |

| 56 | 0.888206 | 0.996107 | 0.978488 |

| 57 | 0.888439 | 0.998532 | 0.978032 |

| 58 | 0.888323 | 1.000683 | 0.978807 |

| 59 | 0.888997 | 1.004337 | 0.976141 |

| 60 | 0.890138 | 1.007615 | 0.974819 |

| 61 | 0.891837 | 1.008639 | 0.977212 |

| 62 | 0.892884 | 1.009664 | 0.976118 |

| 63 | 0.892279 | 1.006522 | 0.975207 |

| 64 | 0.892767 | 1.012293 | 0.973543 |

| 65 | 0.893721 | 1.013693 | 0.971743 |

| 66 | 0.891464 | 1.016561 | 0.968689 |

| 67 | 0.894443 | 1.017142 | 0.9727 |

| 68 | 0.895956 | 1.01984 | 0.975526 |

| 69 | 0.89784 | 1.022742 | 0.975207 |

| 70 | 0.899656 | 1.022469 | 0.974888 |

| 71 | 0.899935 | 1.023527 | 0.974728 |

| 72 | 0.900261 | 1.024859 | 0.972267 |

| 73 | 0.904915 | 1.025405 | 0.974478 |

| 74 | 0.906009 | 1.025098 | 0.974933 |

| 75 | 0.908219 | 1.028615 | 0.975252 |

| 76 | 0.91036 | 1.032986 | 0.97589 |

| 77 | 0.912827 | 1.033737 | 0.97605 |

| 78 | 0.913385 | 1.03384 | 0.974478 |

| 79 | 0.91541 | 1.03524 | 0.976187 |

| 80 | 0.914945 | 1.035001 | 0.978101 |

| 81 | 0.917551 | 1.038108 | 0.977098 |

| 82 | 0.920227 | 1.038928 | 0.978693 |

| 83 | 0.922833 | 1.042411 | 0.976734 |

| 84 | 0.922205 | 1.043811 | 0.975868 |

| 85 | 0.92281 | 1.046372 | 0.977896 |

| 86 | 0.923136 | 1.046713 | 0.977235 |

| 87 | 0.922205 | 1.047601 | 0.97826 |

| 88 | 0.924835 | 1.056684 | 0.98022 |

| 89 | 0.924788 | 1.056718 | 0.979924 |

| 90 | 0.926068 | 1.058562 | 0.978032 |

| 91 | 0.925882 | 1.060099 | 0.976209 |

| 92 | 0.926883 | 1.066621 | 0.975776 |

| 93 | 0.925905 | 1.066792 | 0.976642 |

| 94 | 0.925882 | 1.069626 | 0.975116 |

| 95 | 0.926115 | 1.073792 | 0.977235 |

| 96 | 0.927697 | 1.073212 | 0.976437 |

| 97 | 0.925696 | 1.074748 | 0.978511 |

| 98 | 0.925393 | 1.076695 | 0.979217 |

| 99 | 0.926743 | 1.081134 | 0.980334 |

| 100 | 0.925277 | 1.079495 | 0.976802 |

| 101 | 0.924765 | 1.079426 | 0.978511 |

| 102 | 0.926673 | 1.083456 | 0.980243 |

| 103 | 0.925742 | 1.085026 | 0.980357 |

| 104 | 0.926324 | 1.087758 | 0.983365 |

| 105 | 0.925905 | 1.088236 | 0.980288 |

| 106 | 0.926743 | 1.091173 | 0.982795 |

| 107 | 0.92679 | 1.085983 | 0.979468 |

| 108 | 0.929093 | 1.091958 | 0.982112 |

| 109 | 0.92779 | 1.097012 | 0.982043 |

| 110 | 0.929 | 1.098651 | 0.9812 |

| 111 | 0.93021 | 1.097968 | 0.980813 |

| 112 | 0.93149 | 1.095715 | 0.980402 |

| 113 | 0.933631 | 1.099163 | 0.98398 |

| 114 | 0.931886 | 1.09749 | 0.982385 |

| 115 | 0.934632 | 1.100973 | 0.981792 |

| 116 | 0.935865 | 1.100905 | 0.984687 |

| 117 | 0.937704 | 1.102407 | 0.982772 |

| 118 | 0.940007 | 1.10292 | 0.982499 |

| 119 | 0.942125 | 1.102271 | 0.983752 |

| 120 | 0.942753 | 1.104968 | 0.981884 |

| 121 | 0.945918 | 1.10572 | 0.985849 |

| 122 | 0.947361 | 1.10811 | 0.985621 |

| 123 | 0.949013 | 1.099539 | 0.983502 |

| 124 | 0.949921 | 1.105617 | 0.984937 |

| 125 | 0.951713 | 1.107871 | 0.989153 |

| 126 | 0.95262 | 1.107973 | 0.986008 |

| 127 | 0.953737 | 1.110193 | 0.989312 |

| 128 | 0.95532 | 1.108383 | 0.986213 |

| 129 | 0.957275 | 1.110603 | 0.986418 |

| 130 | 0.958578 | 1.11009 | 0.988287 |

| 131 | 0.959578 | 1.113744 | 0.987877 |

| 132 | 0.959206 | 1.116886 | 0.984299 |

| 133 | 0.960579 | 1.115178 | 0.984595 |

| 134 | 0.959881 | 1.116066 | 0.987353 |

| 135 | 0.95902 | 1.114461 | 0.986715 |

| 136 | 0.958112 | 1.114598 | 0.986191 |

| 137 | 0.958112 | 1.115042 | 0.989495 |

| 138 | 0.955832 | 1.115861 | 0.988971 |

| 139 | 0.956088 | 1.114291 | 0.99068 |

| 140 | 0.954435 | 1.112412 | 0.987649 |

| 141 | 0.946267 | 1.118115 | 0.989404 |

| 142 | 0.951433 | 1.120369 | 0.989745 |

| 143 | 0.950061 | 1.124876 | 0.991728 |

| 144 | 0.948548 | 1.125525 | 0.99542 |

: Employment change since February 2020 business cycle peak, select Midwest industries

| Manufacturing | Leisure & hospitality | State & local govt. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0.997249 | 0.96537 | 0.997729 |

| 2 | 0.849501 | 0.513967 | 0.932844 |

| 3 | 0.874306 | 0.578622 | 0.907362 |

| 4 | 0.930596 | 0.689602 | 0.904427 |

| 5 | 0.93703 | 0.751591 | 0.924495 |

| 6 | 0.941525 | 0.76883 | 0.936101 |

| 7 | 0.946903 | 0.790674 | 0.931697 |

| 8 | 0.950292 | 0.805126 | 0.934106 |

| 9 | 0.951864 | 0.79328 | 0.934266 |

| 10 | 0.956629 | 0.74441 | 0.930665 |

| 11 | 0.959625 | 0.769254 | 0.93406 |

| 12 | 0.959109 | 0.80249 | 0.93305 |

| 13 | 0.963382 | 0.815094 | 0.936284 |

| 14 | 0.956776 | 0.826577 | 0.939908 |

| 15 | 0.955622 | 0.833485 | 0.941514 |

| 16 | 0.958618 | 0.849785 | 0.947913 |

| 17 | 0.963677 | 0.878446 | 0.95656 |

| 18 | 0.963407 | 0.881022 | 0.953876 |

| 19 | 0.965814 | 0.883355 | 0.951147 |

| 20 | 0.972494 | 0.894353 | 0.94805 |

| 21 | 0.973353 | 0.90838 | 0.947959 |

| 22 | 0.977037 | 0.908138 | 0.947706 |

| 23 | 0.980426 | 0.910441 | 0.953234 |

| 24 | 0.984552 | 0.916894 | 0.95172 |

| 25 | 0.98971 | 0.92062 | 0.952615 |

| 26 | 0.99332 | 0.922317 | 0.95305 |

| 27 | 0.993443 | 0.925983 | 0.954266 |

| 28 | 0.994843 | 0.929134 | 0.95656 |

| 29 | 1.000958 | 0.935194 | 0.962982 |

| 30 | 0.937648 | 0.964335 | |

| 31 | 0.939859 | 0.961216 | |

| 32 | 0.946949 | 0.963853 | |

| 33 | 0.955493 | 0.966651 | |

| 34 | 0.957038 | 0.964266 | |

| 35 | 0.962734 | 0.968968 | |

| 36 | 0.967915 | 0.971124 | |

| 37 | 0.969339 | 0.972477 | |

| 38 | 0.972126 | 0.973394 | |

| 39 | 0.973338 | 0.977523 |

Note: “Midwest” refers to the 12 states that make up the region as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Employment Statistics data.

State and local government employment shortfalls in the Midwest and across the country pose harm to workers and communities

The continued weakness in state and local government hiring is a serious problem for the Midwest and the country more broadly. From the start of the pandemic through 2021, employment in state and local public education—which represents the lion’s share of state and local government losses—fell by nearly 5% overall (Cooper and Martinez Hickey 2022). The dire conditions faced by public schools, public health systems, unemployment insurance offices, and other public agencies during the pandemic made clear how critical these public services are, particularly in times of social and economic distress.

In periods of weakened consumer demand, government spending is the primary tool to boost economic growth. This includes spending to support public-sector employment. In the decade following the Great Recession, policymakers in the Midwest largely chose to defund, rather than invest in, public-sector employment. This choice resulted in sluggish overall job growth, persistent high unemployment rates, and real median wages that barely budged (and even declined in several years).

At least in some cases, policies that have eroded public-sector collective bargaining rights have reduced real wages enough that state and local governments are facing soaring job vacancy rates, as workers opt for better-paying jobs in the private sector. A prime example is Wisconsin (Gunn 2023). The passage of Act 10 in 2011, which reduced union rights and limited the ability of local governments to raise public-sector pay, reduced worker wages and household incomes (Cooper 2018). Not only does Wisconsin have 8.5% fewer state and local government jobs than it did before the beginning of the Great Recession, but it is also having trouble filling vacancies for the jobs it still has (BLS-LAUS various years).

In the current economy, the public-sector employment shortfall has not been as pronounced; however, the longer it persists, the more harm it causes both workers and communities. Cuts in public-sector employment are particularly harmful to Black workers and women, who are disproportionately employed in the sector. State and local government has historically been a key source of family-sustaining middle-class jobs, particularly for workers of color (Cooper and Wolfe 2020).

Moreover, a depleted public-sector workforce means that state and local governments are less able to provide essential goods and services, such as public education, unemployment insurance, and other social safety net protections. Within the Midwest, eight states have state and local government employment deficits that exceed the U.S. average: Missouri, Nebraska, Illinois, Michigan, Kansas, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Ohio (see Figure K).

Eight Midwestern states’ losses in state and local government employment exceed the U.S. average: Percent change in state and local government employment between February 2020 and May 2023, Midwestern states and U.S.

| Percent change (Feb 2020–May 2023) | |

|---|---|

| Ohio | -3.9% |

| Wisconsin | -2.9% |

| Minnesota | -2.7% |

| Kansas | -2.6% |

| Michigan | -2.4% |

| Illinois | -2.3% |

| Nebraska | -2.0% |

| Missouri | -1.9% |

| United States | -1.4% |

| North Dakota | -1.2% |

| Iowa | -0.8% |

| Indiana | 0.4% |

| South Dakota | 0.4% |

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Employment Statistics data.

Wages

Low-wage workers have seen historic gains, but median-wage workers are faring worse than in any other region

Policy decisions to not raise minimum wages in six Midwestern states, laws preempting local governments from passing their own minimum wage increases, and legislation weakening unions have had a predictably deleterious effect on wages in the region. No region has seen slower wage growth over the past 15 years.

A significant bright spot of the current recovery—nationwide and in the Midwest—has been the largely unprecedented improvement in wages for the economy’s lowest-paid workers (discussed below). However, the state of typical worker wages in the Midwest is less encouraging. The Midwest fared the worst of any region on the recovery of median wages (the wages of workers in the middle of the wage distribution) in the wake of both the Great Recession and the more recent pandemic recession (see Figure L). Between 2007 and 2010, real (inflation-adjusted) median wages fell across the Midwest, while other regions saw increases in their median wages. Median wages in the Midwest did not start increasing again until 2015.

The Midwest has fared similarly poorly on real median wage growth in the current economic recovery. Between 2019 and 2022, real median wages increased only $0.08 (0.4%) in the Midwest, while the Northeast and West saw increases of over a dollar (5.7% and 4.7%, respectively). Relative to 2007, median wages have grown only 5.8% as of 2022, slower than any other region.3

Following the last two recessions, median wages in the Midwest have grown less than in other regions: Median wage growth by region, 2007–2010 and 2019–2022

| Growth 2007–2010 | Growth 2019–2022 | |

|---|---|---|

| United States | 0.8% | 3.1% |

| Northeast | 3.1% | 5.7% |

| Midwest | -0.9% | 0.4% |

| South | 1.2% | 0.9% |

| West | 0.2% | 4.7% |

Notes: Midwest, Northeast, South, and West refer to the four geographic regions of the United States as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau. Median (50th-percentile) wages are inflation-adjusted to 2022 dollars.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata.

As a result of sluggish wage growth, wage levels in the Midwest lag almost every other region, faring only slightly better than the South—a region known for its low wages, limited worker protections, and hostility to unions (Henderson 2022). As seen in Figure M, in 2022 the median worker was paid $22.10 an hour in the Midwest, lower than the U.S. average of $22.88, and much lower than the median in the West ($24.01) and Northeast ($24.94).

Median wages in the Midwest have been below the U.S. average for the past 15 years: Median hourly wages by region, 1979–2022

| United States | Northeast | Midwest | South | West | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | $19.25 | $19.78 | $20.31 | $17.74 | $21.25 |

| 1980 | $19.11 | $19.52 | $19.96 | $17.18 | $20.91 |

| 1981 | $18.92 | $19.23 | $19.45 | $17.09 | $21.03 |

| 1982 | $18.84 | $19.60 | $19.42 | $17.29 | $21.12 |

| 1982 | $18.88 | $19.78 | $19.39 | $17.03 | $20.87 |

| 1984 | $18.96 | $20.07 | $19.18 | $16.97 | $20.87 |

| 1985 | $19.28 | $20.06 | $19.28 | $17.27 | $21.08 |

| 1986 | $19.42 | $20.75 | $19.29 | $17.86 | $21.55 |

| 1987 | $19.65 | $21.51 | $19.26 | $17.74 | $21.31 |

| 1988 | $19.36 | $21.66 | $19.12 | $17.76 | $21.20 |

| 1989 | $19.34 | $21.77 | $18.93 | $17.44 | $20.78 |

| 1990 | $19.30 | $21.79 | $18.98 | $17.40 | $20.39 |

| 1991 | $19.15 | $21.24 | $18.94 | $17.28 | $20.86 |

| 1992 | $19.34 | $21.38 | $18.64 | $17.45 | $20.56 |

| 1993 | $19.63 | $21.43 | $18.99 | $17.66 | $20.21 |

| 1994 | $19.42 | $21.47 | $18.91 | $17.56 | $20.05 |

| 1995 | $19.14 | $21.29 | $19.08 | $17.59 | $19.62 |

| 1996 | $18.83 | $21.26 | $18.88 | $17.65 | $19.71 |

| 1997 | $19.22 | $21.48 | $19.34 | $18.17 | $19.93 |

| 1998 | $19.90 | $21.74 | $20.04 | $18.25 | $20.65 |

| 1999 | $20.41 | $22.09 | $20.71 | $19.15 | $21.13 |

| 2000 | $20.52 | $22.15 | $20.69 | $19.00 | $21.07 |

| 2001 | $20.83 | $22.99 | $21.07 | $19.82 | $21.45 |

| 2002 | $21.16 | $23.06 | $21.25 | $19.76 | $21.43 |

| 2003 | $21.17 | $23.30 | $21.27 | $19.94 | $22.23 |

| 2004 | $21.42 | $23.21 | $21.46 | $20.11 | $21.99 |

| 2005 | $21.09 | $22.60 | $21.09 | $19.65 | $22.03 |

| 2006 | $21.17 | $22.79 | $21.01 | $20.08 | $21.84 |

| 2007 | $21.21 | $22.77 | $20.89 | $20.01 | $22.03 |

| 2008 | $21.05 | $22.82 | $20.54 | $20.23 | $22.31 |

| 2009 | $21.51 | $23.55 | $20.73 | $20.52 | $22.69 |

| 2010 | $21.38 | $23.49 | $20.70 | $20.24 | $22.09 |

| 2011 | $20.85 | $23.01 | $20.29 | $19.72 | $21.33 |

| 2012 | $20.59 | $22.55 | $20.26 | $19.74 | $21.43 |

| 2013 | $20.69 | $22.61 | $20.27 | $19.72 | $21.33 |

| 2014 | $20.71 | $22.67 | $20.28 | $19.72 | $21.06 |

| 2015 | $21.06 | $23.38 | $20.84 | $20.02 | $21.42 |

| 2016 | $21.43 | $23.48 | $20.95 | $20.53 | $22.05 |

| 2017 | $21.62 | $23.86 | $21.41 | $20.67 | $22.35 |

| 2018 | $21.98 | $23.49 | $21.61 | $20.90 | $22.56 |

| 2019 | $22.19 | $23.59 | $22.02 | $21.30 | $22.94 |

| 2020 | $23.70 | $26.14 | $22.84 | $22.65 | $24.63 |

| 2021 | $23.08 | $25.74 | $22.75 | $21.65 | $23.88 |

| 2022 | $22.88 | $24.94 | $22.10 | $21.50 | $24.01 |

Notes: Midwest, Northeast, South, and West refer to the four geographic regions of the United States as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau. Median (50th percentile) wages are inflation-adjusted to 2022 dollars.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata.

As shown in Figure N, the Midwest-to-U.S. median wage ratio—that is, the Midwest median wage relative to (divided by) the U.S. median wage—has been on a downward trajectory since 1979. Additionally, the relative median wage has declined more in the Midwest than in any other region—8.4% between 1979 and 2022.

In 1979, the typical worker in the Midwest earned 5.5% above the typical worker nationwide, bested only by the typical (median) worker in the West, who made 10.4% more than the national median worker. By 2007, after three decades of active hostility toward unions, trade policy that incentivized offshoring, and the erosion of various labor standards, the median worker in the Midwest was paid 1.5% less than the median worker nationwide.

Notably, this decline in the relative wages of typical Midwest workers persists today. In 2022, the median wage in the Midwest was 3.4% less than the national median—only slightly higher than the 6% lower median wage of workers in the South.

The Midwest-to-U.S. median wage ratio has declined more in the Midwest than in any other region: Relative median wage by region, select years

| South | West | Northeast | Midwest | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 0.922 | 1.104 | 1.027 | 1.055 |

| 2007 | 0.943 | 1.039 | 1.074 | 0.985 |

| 2022 | 0.940 | 1.049 | 1.090 | 0.966 |

Notes: Midwest, Northeast, South, and West refer to the four geographic regions of the United States as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau. The relative median wage is the ratio of the regional median wage to the U.S. median wage, where 1 indicates that a region's median wage is identical to the national median. Median (50th percentile) wages are in nominal terms (are not adjusted for inflation).

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata.

Half of Midwestern states experienced median wage growth since 2019, but 10 states’ median wages are still lower than the national median

Within the Midwest, there has been significant variability in median wage growth over the past two economic downturns, so it is useful to examine state-by-state dynamics.

While the country and the Midwest region overall fared better in the recovery from the pandemic recession than in the recovery from the Great Recession, Ohio, Iowa, South Dakota, and Missouri fared worse, and Wisconsin’s wage growth was flat (see Figure O).

Between 2007 and 2010, in the wake of the Great Recession, median wages grew most significantly in North Dakota, South Dakota, and Nebraska, largely due to the fracking boom of the early aughts and its ripple effects in neighboring states (Rusyn 2015). Yet these gains appear to have been short-lived in North Dakota and South Dakota, where median wages barely grew (North Dakota) or even declined (South Dakota) over the last three years. As demand for, and prices of, natural gas have flattened, the job market (and thus wage growth) for these states has cooled (Rickman and Wang 2018). In Nebraska, wages increased from 2019 to 2022. Nonetheless, wages in these three states remain below the national median of $22.88.

Minnesota and Illinois were the only Midwestern states with median wages above the national median in 2022, and they are the only two Midwestern states with median wages that are consistently above the national median. In Minnesota, wages have been an average of nearly two dollars ($1.87) higher than the U.S. median over the past 15 years. In Illinois, median wages have been an average of $0.64 above the national median (see Appendix Table 2).

Half of Midwestern states fared better on wage growth this recovery than in the recovery following the Great Recession, but half fared worse: Median wage growth in Midwestern states, 2007–2010 and 2019–2022

| 2007–2010 | 2019–2022 | |

|---|---|---|

| Kansas | 0.03% | 7.09% |

| Nebraska | 2.91% | 6.74% |

| Minnesota | 1.99% | 6.31% |

| Indiana | -2.17% | 5.89% |

| Michigan | -0.69% | 5.71% |

| United States | 0.79% | 3.41% |

| Illinois | 1.20% | 3.14% |

| North Dakota | 8.16% | 0.79% |

| Wisconsin | 1.95% | -0.01% |

| Iowa | 2.13% | -0.59% |

| Ohio | -0.91% | -1.40% |

| Missouri | 1.08% | -1.61% |

| South Dakota | 3.41% | -1.79% |

Note: Median wages are inflation-adjusted to 2022 dollars.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata.

Low-wage workers have seen strong gains in the current recovery, but 10th-percentile wages remain too low and the Midwest’s low-wage workforce remains large

Despite sluggish wage growth at the median, low-wage workers in the Midwest have seen large gains in the current recovery. The 10th-percentile wage—the value at which only 10% of workers are paid less and 90% of workers are paid more—has risen 8.6% since 2019. This is, by a wide margin, the fastest wage gain at the 10th percentile of any three-year business cycle since 1979 and an over-fivefold increase compared with the post–Great Recession recovery (see Figure P). These wage gains are largely the result of substantial federal spending bills passed in 2020 and 2021. These spending packages prevented a steep drop-off in economic demand, kept numerous businesses afloat, and fueled a tight job market, leading to an increase in wages for the lowest-paid workers across the whole country (Gould and deCourcy 2023).

The Midwest’s lowest-paid workers have seen strong gains over the current recovery: Real wage changes at the 10th percentile in the Midwest over five business cycles, 1979–2022

| Business cycle | 10th percentile |

|---|---|

| 1979–1982 | -12.04% |

| 1989–1992 | 4.49% |

| 2001–2004 | -1.17% |

| 2007–2010 | 1.55% |

| 2019–2022 | 8.56% |

Notes: “Midwest” refers to the 12 states that make up the region as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau. Tenth-percentile wages are inflation-adjusted to 2022 dollars.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata.

As shown in Figure Q, the “dot-com” bubble of the late 1990s and early 2000s was marked by a tight labor market and fast wage growth—at the time, the period of fastest wage growth since the 1950s. The bubble burst in 2000 and the U.S. economy entered a recession. However, wage growth at the 10th percentile continued to rise until 2002. This was due to composition effects (not for positive reasons): Low-wage workers disproportionately lose their jobs in economic downturns, so the resulting wage distribution skews upward.

In 2002, 10th-percentile wages in the Midwest were nearly identical to those in the Northeast and West (see Figure Q). However, in the decades that followed, the Midwest began to fall further behind the West and Northeast. This trend became particularly pronounced after 2010, when conservative lawmakers took power in many Midwestern states and began weakening—or failing to strengthen—labor standards.

As other regions more aggressively raised the minimum wage, Republican-controlled Midwestern states did not. Many instead adopted preemption laws preventing local jurisdictions from enacting higher minimum wages.

Every region, including the Midwest, has made significant progress on raising the wages of the lowest-paid workers over the past three decades. But despite gradual gains over time, the 10th-percentile wage—$12.45 in the Midwest in 2022—remains too low for workers to make ends meet in any part of the region (EPI 2022).

Despite significant gains, workers at the bottom of the Midwest’s pay distribution fare worse than the U.S. average: 10th-percentile hourly wages by region, 1979–2022

| Midwest | U.S. | South | West | Northeast | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | $11.16 | $11.16 | $11.01 | $11.39 | $11.27 |

| 1980 | $10.41 | $10.41 | $10.21 | $10.78 | $10.61 |

| 1981 | $10.25 | $10.25 | $10.04 | $10.66 | $10.44 |

| 1982 | $9.82 | $9.85 | $9.61 | $10.31 | $10.14 |

| 1983 | $9.41 | $9.53 | $9.30 | $9.97 | $9.83 |

| 1984 | $9.20 | $9.33 | $9.04 | $9.85 | $9.71 |

| 1985 | $8.97 | $9.21 | $8.92 | $9.80 | $9.78 |

| 1986 | $9.02 | $9.25 | $8.92 | $9.79 | $9.99 |

| 1987 | $8.90 | $9.24 | $8.82 | $9.64 | $10.03 |

| 1988 | $8.97 | $9.32 | $8.75 | $9.85 | $10.45 |

| 1989 | $9.03 | $9.25 | $8.77 | $9.89 | $10.53 |

| 1990 | $8.97 | $9.32 | $8.75 | $9.78 | $10.76 |

| 1991 | $9.31 | $9.48 | $9.08 | $10.04 | $10.46 |

| 1992 | $9.43 | $9.55 | $9.10 | $10.02 | $10.31 |

| 1993 | $9.58 | $9.70 | $9.12 | $9.84 | $10.18 |

| 1994 | $9.62 | $9.62 | $9.11 | $9.72 | $9.93 |

| 1995 | $9.56 | $9.53 | $9.35 | $9.54 | $9.83 |

| 1996 | $9.52 | $9.41 | $9.24 | $9.43 | $9.80 |

| 1997 | $9.87 | $9.68 | $9.45 | $9.70 | $10.07 |

| 1998 | $10.49 | $10.29 | $9.90 | $10.49 | $10.62 |

| 1999 | $10.61 | $10.48 | $10.31 | $10.50 | $10.59 |

| 2000 | $10.87 | $10.41 | $10.21 | $10.50 | $10.75 |

| 2001 | $10.97 | $10.74 | $10.26 | $10.84 | $11.35 |

| 2002 | $11.25 | $11.08 | $10.47 | $11.24 | $11.37 |

| 2003 | $11.05 | $11.02 | $10.46 | $11.18 | $11.20 |

| 2004 | $10.84 | $10.82 | $10.61 | $10.96 | $10.98 |

| 2005 | $10.57 | $10.56 | $10.38 | $10.71 | $10.93 |

| 2006 | $10.42 | $10.50 | $10.24 | $10.77 | $11.00 |

| 2007 | $10.58 | $10.68 | $10.30 | $11.18 | $11.18 |

| 2008 | $10.49 | $10.80 | $10.29 | $11.01 | $10.97 |

| 2009 | $10.80 | $10.90 | $10.46 | $11.28 | $11.06 |

| 2010 | $10.75 | $10.80 | $10.61 | $11.28 | $11.00 |

| 2011 | $10.47 | $10.52 | $10.35 | $10.97 | $10.95 |

| 2012 | $10.33 | $10.34 | $10.18 | $10.81 | $10.71 |

| 2013 | $10.33 | $10.41 | $10.13 | $10.81 | $10.74 |

| 2014 | $10.37 | $10.50 | $10.05 | $11.06 | $10.90 |

| 2015 | $10.96 | $11.00 | $10.42 | $11.20 | $11.14 |

| 2016 | $11.02 | $11.10 | $10.84 | $12.07 | $11.58 |

| 2017 | $11.34 | $11.56 | $10.78 | $12.00 | $11.89 |

| 2018 | $11.57 | $11.62 | $11.02 | $12.35 | $11.76 |

| 2019 | $11.47 | $11.53 | $11.33 | $12.78 | $12.48 |

| 2020 | $12.32 | $12.45 | $11.40 | $13.63 | $13.43 |

| 2021 | $12.45 | $12.65 | $11.45 | $13.88 | $13.39 |

| 2022 | $12.45 | $12.57 | $11.93 | $14.09 | $13.39 |

Note: Midwest, Northeast, South, and West refer to the four geographic regions of the United States as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau. Tenth-percentile wages are inflation-adjusted to 2022 dollars.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata.

Another way to evaluate the progress made in improving pay for low-wage workers is to look at the share of the workforce earning less than $15 per hour. As shown in Figure R, there have been steep declines nationwide in the share of workers earning less than $15 an hour in the years since 2015. During this time, the Midwest’s share has been nearly halved (28.1% in 2015, 14.7% in 2022). This shows good progress for low-wage workers overall.

Over the last two decades, the Midwest has persistently had the second-highest share of workers earning less than $15 of any region, with only the South having a higher share (20.2% in 2022). The 14.7% share of the Midwestern workforce paid less than $15 an hour in 2022 amounts to nearly 4.5 million workers throughout the region. In three states, over half a million of the state’s workers are paid less than $15 an hour: Ohio (835,000), Illinois (720,000), and Michigan (671,000) (EPI analysis of BLS-CPS various years). In Ohio, Iowa, and Kansas, that amounts to 1 in 6 workers (Figure S).

The Midwest has consistently employed the second-largest regional share of low-wage workers over the last two decades: Share of workers earning less than $15 an hour by region, 1994–2022

| Year | South | West | Northeast | Midwest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 36.9% | 29.5% | 25.8% | 32.1% |

| 1995 | 36.3% | 30.4% | 25.2% | 31.8% |

| 1996 | 38.4% | 31.6% | 27.0% | 32.7% |

| 1997 | 36.4% | 31.6% | 26.6% | 31.2% |

| 1998 | 34.4% | 29.2% | 25.2% | 28.8% |

| 1999 | 31.7% | 26.3% | 23.2% | 25.9% |

| 2000 | 32.0% | 26.7% | 23.2% | 24.9% |

| 2001 | 31.7% | 26.0% | 22.0% | 25.2% |

| 2002 | 29.7% | 24.9% | 21.7% | 24.4% |

| 2003 | 29.8% | 24.1% | 20.5% | 24.2% |

| 2004 | 30.2% | 23.6% | 20.9% | 24.6% |

| 2005 | 28.7% | 23.0% | 20.5% | 24.3% |

| 2006 | 31.9% | 26.3% | 23.5% | 27.3% |

| 2007 | 31.2% | 25.1% | 23.2% | 28.2% |

| 2008 | 29.8% | 22.8% | 21.9% | 27.4% |

| 2009 | 29.5% | 23.7% | 21.1% | 26.7% |

| 2010 | 31.7% | 25.1% | 23.0% | 28.8% |

| 2011 | 31.8% | 26.1% | 22.7% | 28.8% |

| 2012 | 31.4% | 26.3% | 23.8% | 29.3% |

| 2013 | 31.5% | 26.4% | 23.3% | 28.1% |

| 2014 | 32.8% | 28.3% | 24.7% | 29.2% |

| 2015 | 31.2% | 26.6% | 22.7% | 28.1% |

| 2016 | 29.5% | 23.9% | 22.7% | 26.7% |

| 2017 | 29.1% | 23.6% | 20.8% | 25.7% |

| 2018 | 27.3% | 19.4% | 18.7% | 23.2% |

| 2019 | 26.0% | 17.5% | 17.4% | 22.2% |

| 2020 | 22.4% | 12.3% | 13.0% | 18.2% |

| 2021 | 22.0% | 9.7% | 11.5% | 16.6% |

| 2022 | 20.2% | 8.0% | 10.2% | 14.7% |

Note: Midwest, Northeast, South, and West refer to the four geographic regions of the United States as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Source: Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group extracts, Version 1.0.40.

In Ohio, Iowa, and Kansas, one in six workers are paid less than $15 an hour: Share of workers earning less than $15 an hour in Midwestern states, 2022

| State | Share of workers earning less than $15 |

|---|---|

| Kansas | 17.7% |

| Iowa | 17.5% |

| Ohio | 16.8% |

| Missouri | 16.3% |

| Michigan | 16.0% |

| Indiana | 15.8% |

| Wisconsin | 14.3% |

| South Dakota | 14.0% |

| Nebraska | 13.6% |

| Illinois | 12.9% |

| North Dakota | 10.8% |

| Minnesota | 8.6% |

Source: EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group extracts, Version 1.0.40: Economic Policy Institute.

Safety net and worker protections

Federal legislation during the pandemic greatly expanded unemployment benefits and introduced limited but important paid leave benefits. This federal intervention ran counter to the pre-pandemic trend in most Midwestern states to weaken unemployment insurance protection and prevent local governments from enacting paid leave provisions. In the wake of the pandemic, some Midwestern states are following the federal government’s lead and strengthening the safety net. However, many more are adopting policies that mark a return to pre-pandemic austerity.

The Midwest lags other regions on paid sick leave, both as an employer benefit and as a legal right

A common statistic used to understand paid sick leave access is the share of private-sector workers who report receiving paid sick days as an employer-provided benefit. In the Midwest, 72% of private-sector workers report having access to paid sick leave.