Summary: The large increase in inflation in 2021 and 2022 in the United States exposed just how little deep thinking had been done about the issue of inflation-control by macroeconomists and policy makers in preceding decades. The inflation of that time has often been attributed entirely to an excess of aggregate demand over potential output. But these years saw historically large shocks to the real economy stemming from COVID-19 and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. These shocks imposed extreme distortions on sectoral demand and supply, distortions which seem to have generated inflation globally, not just in the U.S. Further, temporary policies and circumstances (particularly pandemic fiscal relief and the whipsaw of massive layoffs and rapid rehiring efforts in labor-intensive service sectors) gave U.S. workers a pronounced but temporary boost in wage-bargaining with employers. Accordingly, a “shocks and ripples” analysis of inflation explains the data better than analyses based on movements in aggregate demand and supply.1

Starting in mid-2021, inflation in the United States rose to levels not seen since the early 1980s. This inflation followed on the heels of the economic shock imposed by the global COVID-19 pandemic and the significant fiscal policy interventions meant to smooth the fallout of this shock. As of October 2022, inflation—both headline and core measures—remained at historically high levels, though there are significant signs of softening in the near future (evidenced in part by the bending down of the quarterly data series shown in Figure A).

Inflation’s 2021 rise and potential 2023 fall: Overall and core (excluding food and energy) inflation, year-over-year and quarterly at an annualized rate, 2017–2022

| Overall, year-over-year | Core, year-over-year | Overall, quarterly (annualized) | Core, quarterly (annualized) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017Q1 | 2.1% | 1.9% | 2.4% | 1.9% |

| 2017Q2 | 1.7% | 1.7% | 1.0% | 1.5% |

| 2017Q3 | 1.7% | 1.5% | 1.5% | 1.3% |

| 2017Q4 | 1.9% | 1.7% | 2.6% | 2.0% |

| 2018Q1 | 2.0% | 1.9% | 2.9% | 2.6% |

| 2018Q2 | 2.3% | 2.0% | 2.2% | 2.2% |

| 2018Q3 | 2.3% | 2.1% | 1.4% | 1.4% |

| 2018Q4 | 2.0% | 2.0% | 1.5% | 1.9% |

| 2019Q1 | 1.5% | 1.7% | 0.8% | 1.5% |

| 2019Q2 | 1.6% | 1.7% | 2.5% | 2.1% |

| 2019Q3 | 1.5% | 1.8% | 1.0% | 1.6% |

| 2019Q4 | 1.5% | 1.6% | 1.5% | 1.2% |

| 2020Q1 | 1.6% | 1.7% | 1.5% | 1.9% |

| 2020Q2 | 0.5% | 0.9% | -1.8% | -1.0% |

| 2020Q3 | 1.1% | 1.3% | 3.4% | 3.2% |

| 2020Q4 | 1.2% | 1.4% | 1.6% | 1.5% |

| 2021Q1 | 1.9% | 1.7% | 4.5% | 3.2% |

| 2021Q2 | 4.0% | 3.5% | 6.4% | 6.0% |

| 2021Q3 | 4.5% | 3.9% | 5.6% | 4.8% |

| 2021Q4 | 5.7% | 4.7% | 6.2% | 4.8% |

| 2022Q1 | 6.4% | 5.3% | 7.5% | 5.6% |

| 2022Q2 | 6.6% | 5.0% | 7.3% | 4.7% |

| 2022Q3 | 6.3% | 4.9% | 4.2% | 4.5% |

Source: Price deflator for personal consumption expenditures (PCEPI) taken from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA).

This episode has sparked furious debate over the proper policy response, and it has exposed how little innovative thinking has been done on inflation by either macroeconomists or policy analysts since the 1980s price acceleration was ended by the Volcker shock. This report identifies a number of key questions raised by the inflationary outbreak of the past 18 months and offers some answers. A brief summary of these questions and answers is provided below. The remainder of the report then expands on these points.

Why did inflation surge in 2021 and remain high throughout 2022?

The evidence that the simplest stories of macroeconomic “overheating” adequately explain the inflation of the past 18 months is extremely mixed. The evidence is more consistent with a story of extreme shocks causing sectoral demand and supply imbalances, and these sectoral shocks in turn causing unexpectedly large ripple effects in the wider economy through distributional conflict over which groups would absorb the economic losses from higher prices.

What was the role of the COVID pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine in driving this inflationary surge?

The pandemic led to a historically sharp reallocation of consumer spending away from face-to-face services and toward goods consumption and residential investment. Simultaneously, the pandemic introduced huge snarls in global supply chains that need to function smoothly to meet demand for goods and materials used in residential investment. These extreme shocks to both sectoral demand and supply were the spark to inflation in 2021. In 2022, the Russian invasion of Ukraine added another, more familiar shock, to energy and food prices. Both the direct effects of the invasion and the international response of sanctions reduced the supply of energy and food, sending inflation in these sectors historically high. Many of these shocks were far more persistent than is commonly recognized.

Would a looser labor market and higher unemployment have allowed us to see a more subdued path of inflation over the past 18 months?

These largely sectoral shocks bled over into wider macroeconomic effects in part due to labor markets. Nominal wage growth accelerated noticeably in late 2021 and early 2022, even when the odd compositional effects of the pandemic on the labor market are accounted for. However, this effect of labor market tightness is often overstated as a primary driver of inflation. Most of the initial rise in prices did not come from wage-push factors, and the amount of reduced inflation that could have been “bought” by keeping unemployment higher and nominal wage growth more tame would have been relatively small. The price of this slightly slower inflation would have been even larger declines in real wages for working families.

What was the role of mark-ups in the rise of inflation?

The growth of profit margins contributed a historically large amount to inflationary pressures over the past 18 months. In normal times, profit margins constitute roughly 11% of overall output costs. But growth in these margins contributed well over half of the rise in prices in the nonfinancial corporate sector through the end of 2021. The fact of this large spike in profit margins and the distribution of the rise in these margins across sectors more strongly supports a view that recent inflation has been caused by a “shocks and ripples” effect rather than a simple imbalance between aggregate demand and potential output (i.e., macroeconomic overheating).

With the virtue of hindsight, what policy decisions could have been made differently?

Quite heterodox inflation-fighting tools would have been needed to match up tightly with the inflation we saw in 2021 and 2022. For example, policies that deferred consumer demand on goods could have greatly lessened inflationary pressures. Or an explicitly temporary excess profits tax—implemented quickly and early in 2021—might have restrained margin growth.

Some might argue that the Federal Reserve should have started raising interest rates sooner. We would argue that that is not true. The most compelling case that the Federal Reserve should have started raising rates sooner comes from the effect of rate increases on housing. However, the evidence supporting this housing-based case is mixed.

What was the role of housing in the inflation of 2021–2022 and how should it affect policymaking going forward?

Housing is by far the largest single component of consumption spending and accounts for nearly 40% of core spending in the consumer price index (CPI). It is also the component whose price measurement is most backward-looking. Actual increases in rental inflation, for example, only start to reliably push up housing costs as measured in the CPI over the next 6–12 months.

COVID-19 and the rise of remote work led to a large positive shock to housing demand in 2021. Failure to appreciate the backward-looking dynamics of housing price changes led many to be behind the curve on both the rise and fall of prices in 2021–2022.

Further, housing prices (including rents) have more complicated responses to interest rate increases than other components of price indices. For these and other reasons, policymakers should think hard about housing markets, specifically in the context of debates about inflation control and macroeconomic slack.

What insights from previous historical debates about inflation have been missed in this episode, and why?

In the debate over the inflationary periods of the 1960s and 1970s, much greater attention was paid to issues like the inertia of inflation and how distributional conflict over resources could lead to inflation propagation. Further, the role of sectoral, not macroeconomic, imbalances of supply and demand were taken seriously in previous inflation debates.

In the current debate, it has been striking how confidently many have proclaimed that the mere existence of inflation provides ipso facto evidence that the economy has run into a macroeconomic imbalance of aggregate demand exceeding potential output. This conflation of any inflation with macroeconomic imbalances has been a real loss of knowledge that should be reclaimed.

Macroeconomic overheating is not necessarily the culprit for the inflationary surge of 2021 and 2022

In early 2021, debate raged about the potential economic effects of the American Rescue Plan (ARP). ARP, passed in early 2021, was explicitly designed as fiscal stimulus, with large and front-loaded transfers to households as its centerpiece, along with substantial aid to state and local governments.

Some critics of ARP worried about its potential effect on inflation. The most famous of these worriers was Larry Summers. Summers explicitly framed his concerns as centered around estimates of potential output. He posited that excess fiscal stimulus would push gross domestic product (GDP) well over the economy’s long-run potential to deliver, hence causing inflation. As he put it:

I agree with the general consensus of progressive economists that it would have been much better if the Obama administration had been able to legislate a much larger fiscal stimulus in early 2009, in response to the Great Recession. Yet a comparison of the 2009 stimulus and what is now being proposed is instructive. In 2009, the gap between actual and estimated potential output was about $80 billion a month and increasing. The 2009 stimulus measures provided an incremental $30 billion to $40 billion a month during 2009—an amount equal to about half the output shortfall.

In contrast, recent Congressional Budget Office estimates suggest that with the already enacted $900 billion package—but without any new stimulus—the gap between actual and potential output will decline from about $50 billion a month at the beginning of the year to $20 billion a month at its end. The proposed stimulus will total in the neighborhood of $150 billion a month, even before consideration of any follow-on measures. That is at least three times the size of the output shortfall. (Summers 2021)

This argument might benefit from an illustrative figure. The green line in Figure B shows the estimates of potential output referenced by Summers (“GDP in overheating scenario”). The blue line shows the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO’s) predictions of what GDP growth would have been without ARP through the end of 2020, and actual GDP growth since that date. We then add in a line showing the path GDP would have taken had ARP pushed up actual GDP 1-for-1 with spending, leading real GDP to exceed potential in the manner described by Summers. In this figure, one can see the still considerable negative output gap (shortfall of actual GDP relative to potential) that persisted at the end of 2020, as well as the very large positive output gap that was projected by reasoning like Summers’s after ARP’s passage by the end of 2022.

What overheating pursuant to American Rescue Plan spending would have looked like: Measures and projections of real and potential GDP ($billions)

| CBO est. of potential output in January 2021 | GDP in overheating scenario | Actual GDP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019Q4 | 19157.1 | 19215.7 | 19215.7 |

| 2020Q1 | 19250.2 | 18989.9 | 18989.9 |

| 2020Q2 | 19340.2 | 17378.7 | 17378.7 |

| 2020Q3 | 19424.2 | 18743.7 | 18743.7 |

| 2020Q4 | 19512 | 18924.3 | 18924.3 |

| 2021Q1 | 19602.5 | 19666.2 | 19216.2 |

| 2021Q2 | 19697.4 | 20116.2 | 19544.2 |

| 2021Q3 | 19795.8 | 20566.2 | 19672.6 |

| 2021Q4 | 19898.3 | 21016.2 | 20006.2 |

| 2022Q1 | 20003.7 | 21466.2 | 19924.1 |

| 2022Q2 | 20109.9 | 21916.2 | 19895.3 |

| 2022Q3 | 20216.1 | 22366.2 | 20021.7 |

Note: The green line takes the Congressional Budget Office (2021) forecast of actual GDP and assumes American Rescue Plan fiscal impulse translated 1:1 into higher GDP, per the concerns of some at the time.

Source: Data taken from Congressional Budget Office (2021) and Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA).

The emergence of higher levels of inflation by mid-2021 led many to assume this output gap-based reasoning had turned out to be true. They thought that the inflation was clearly the result of macroeconomic overheating (with the level of actual GDP far exceeding the level of potential GDP). But it is far from obvious that this is the correct interpretation. For one (as we show later), even with the American Rescue Plan, real GDP growth (the red line) has barely beaten pre-pandemic projections of what it would be by mid-2022.

Below we highlight evidence that further complicates the narrative that inflation is the result of simple macroeconomic imbalances driven by a too generous ARP.

International evidence complicates the domestic overheating story

The most straightforward reason to doubt this narrative comes from a look at the international experience of inflation.

A look across member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) shows that rising inflation was not unique to the U.S. and was in fact a global phenomenon throughout 2021 and 2022. Figure C shows the acceleration in core inflation from May 2021 through September 2022, compared with two years of pre-pandemic “normal” inflation (2018–2019), for 35 OECD countries. We use core inflation, which strips out food and energy prices, to better represent broad inflationary pressures in each economy. Using core inflation also allows for a better comparison between the U.S. and Europe given the volatility in food and energy prices affecting Europe due to the war in Ukraine.

The rise of inflation was global in 2021 and 2022: Acceleration of core inflation from May 2021 through September 2022, compared with two years of pre-pandemic “normal” inflation (2018–2019)

| Country | Acceleration of core inflation |

|---|---|

| JPN | 0.7% |

| CHE | 1.7% |

| FRA | 2.4% |

| ESP | 2.8% |

| NOR | 3.1% |

| KOR | 3.7% |

| ITA | 3.8% |

| LUX | 3.8% |

| NLD | 4.2% |

| DNK | 4.4% |

| DEU | 4.5% |

| MEX | 4.6% |

| BEL | 4.6% |

| CAN | 4.7% |

| FIN | 4.8% |

| ISR | 5.1% |

| Non-US median | 5.2% |

| GRC | 5.2% |

| COL | 5.3% |

| IRL | 5.3% |

| AUT | 5.5% |

| GBR | 5.6% |

| SVN | 5.9% |

| USA | 6.0% |

| Non-US average | 6.1% |

| SWE | 6.4% |

| PRT | 6.8% |

| LVA | 7.2% |

| ISL | 7.5% |

| CHL | 9.9% |

| POL | 10.2% |

| LTU | 10.9% |

| SVK | 11.3% |

| HUN | 11.5% |

| EST | 12.2% |

| CZE | 14.4% |

Note: The acceleration of core inflation is measured as the annualized rate of inflation from May 2021 to September 2022 minus the average rate of inflation that prevailed in 2018–2019.

Source: Data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD 2022).

As Figure C shows, all 35 OECD nations we examined experienced an acceleration in core inflation throughout 2021 and 2022 compared with the pre-pandemic period. While above the median, and on the higher side of inflation experiences worldwide, the U.S. is by no means an outlier and is just below the average for all other OECD countries. This global phenomenon of rising inflation casts doubt on the claim that U.S. inflation was caused purely by domestic policy decisions leading to macroeconomic overheating.

One might argue that the global acceleration in inflation simply meant that many countries overheated their economies and generated excess demand through too much fiscal spending. However, the data do not support this argument. For one, Figure C shows OECD nations with a wide range of fiscal responses, from aggressive relief spending to little intervention. Despite the varying responses, all countries experienced some level of inflation acceleration.

Figure D examines more closely the argument that global inflation is simply a reflection of global excess demand. To do this, we examine core inflation acceleration on the vertical axis (the same numbers shown in Figure C). On the horizontal axis, we show change in unemployment between September 2022 and the pre-pandemic 2018–2019 unemployment. This measure indicates how much unemployment has improved recently compared with the pre-pandemic period (for example, a fall in the unemployment rate of 2 percentage points would be shown on the graph as a positive 2%). If inflation was caused by excess demand growth (proxied by lower unemployment rates today), one would expect to see a positive relationship between unemployment improvement and acceleration of inflation. The data do not show this.

Very hard to see global overheating: Unemployment improvement and inflation acceleration across countries

| Unemployment improvement | Inflation acceleration | |

|---|---|---|

| AUT | 0.36 | 5.5% |

| BEL | 0.02 | 4.6% |

| CAN | 0.69 | 4.7% |

| CHL | -0.33 | 9.9% |

| COL | -1.06 | 5.3% |

| CZE | -0.23 | 14.4% |

| DEU | 0.10 | 4.5% |

| DNK | 0.80 | 4.4% |

| ESP | 1.92 | 2.8% |

| EST | -0.75 | 12.2% |

| FIN | 0.31 | 4.8% |

| FRA | 1.30 | 2.4% |

| GBR | 0.25 | 5.6% |

| HUN | 0.02 | 11.5% |

| IRL | 0.96 | 5.3% |

| ISL | -0.47 | 7.5% |

| ISR | 0.32 | 5.1% |

| ITA | 2.20 | 3.8% |

| JPN | -0.18 | 0.7% |

| KOR | 1.07 | 3.7% |

| LTU | 0.85 | 10.9% |

| LUX | 1.21 | 3.8% |

| LVA | 0.30 | 7.2% |

| MEX | 0.12 | 4.6% |

| NLD | 1.16 | 4.2% |

| NOR | 0.76 | 3.1% |

| POL | 0.97 | 10.2% |

| PRT | 0.95 | 6.8% |

| SVK | 0.03 | 11.3% |

| SVN | 0.52 | 5.9% |

| SWE | -0.61 | 6.4% |

| USA | 0.20 | 6.0% |

Notes: The acceleration of core inflation is measured as the annualized rate of inflation from May 2021 to September 2022 minus the average rate of inflation that prevailed in 2018–2019. The improvement in unemployment is average unemployment in 2019 minus unemployment rate that prevailed as of September 2022.

Source: Data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD 2022).

As Figure D depicts, there is no significant positive relationship between unemployment improvement and inflation acceleration. If anything, there appears to be a slightly weak relationship in the opposite direction whereby countries with higher unemployment (or lower improvement) relative to pre-pandemic times experienced higher inflation levels. The fact that countries with larger decreases in unemployment (perhaps brought about by more expansive fiscal policy and economic stimulus) do not show larger spikes in inflation strongly complicates the claim that macroeconomic overheating applies globally.

Overall, the shared 2021–2022 international experience of high core inflation strongly counters the argument that fiscal relief in the U.S.—such as the American Rescue Plan—either drove up inflation or contributed significantly to its unusual persistence.

Domestic evidence is also underwhelming for simple overheating explanations

Turning to the domestic U.S. evidence, the case for recent inflation being sparked by a simple macroeconomic imbalance of aggregate demand and potential output is also weak. Many have presented the steepening trend in nominal spending over the past year and a half as evidence for the overheating view. This is tautological. Faster nominal spending growth could simply be a reflection of faster inflation; it is not evidence of its cause.

Take a totally trivial example: Imagine there was a rapid consolidation of market concentration across the economy. Firms with greater market power would likely raise prices. If the price elasticity of demand was relatively low in the short run (which seems like a safe bet), this would in turn make nominal spending rise more rapidly (even while real spending would actually fall). This could happen with no implication at all for the state of macroeconomic balance.

More realistically, one could imagine a scenario—like what happened following the pandemic shock—wherein the allocation of demand across spending categories rotated sharply into sectors with either impaired supply or a higher elasticity of prices with respect to demand. As this happened, there would be an increase in prices even without the level of aggregate demand being particularly high relative to the economy’s potential output. In the long run, the inflationary effect of very large relative price changes set off by such a process could be muffled by macroeconomic policy, but claims that over a 1–2 year period such relative price changes cannot be major drivers of inflation seem obviously wrong.

Decomposition of inflation into ‘demand’ and ‘supply’ factors

One method some have used to assess the role of ARP and excess stimulus in generating inflation is to decompose the recent acceleration of inflation into “demand” versus “supply” factors. Probably the most well-done and transparent version of this exercise is by Shapiro (2022). The categorization of price changes in a given economic sector as being driven by demand or supply is done by estimating the price and quantity levels of an industry in each month. Then, the “unexpected” components of monthly changes (basically those that exceed or lag a running trend) in both prices and quantities are extracted. If a sector sees both price and quantity growth above trend, price increases in that sector are categorized as demand-driven. If price growth is above trend but quantity growth is below trend, then price increases are characterized as supply-driven. If either price or quantity growth is near trend, then the industry’s price growth is labeled ambiguous.

The Shapiro (2022) decomposition is certainly clever. Based on these results, the rise of core inflation over the past year can essentially be attributed equally to demand- and supply-side measures. This decomposition for recent years is reproduced in Figure E. However, this technique and how its results are interpreted have a couple of potential shortcomings.

Inflation is both a demand and supply phenomenon: Decomposition of core inflation into demand-and supply-driven contributions, by month, 2017–2022

| Demand-driven inflation | Ambiguous | Supply-driven inflation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jan 2017 | 0.409999996% | 0.569999993% | 0.930000007% |

| Feb 2017 | 0.340000004 | 0.560000002 | 1 |

| Mar 2017 | 0.340000004 | 0.5 | 0.870000005 |

| Apr 2017 | 0.360000014 | 0.479999989 | 0.879999995 |

| May 2017 | 0.389999986 | 0.400000006 | 0.879999995 |

| Jun 2017 | 0.400000006 | 0.400000006 | 0.920000017 |

| Jul 2017 | 0.400000006 | 0.340000004 | 0.870000005 |

| Aug 2017 | 0.439999998 | 0.310000002 | 0.779999971 |

| Sep 2017 | 0.479999989 | 0.430000007 | 0.649999976 |

| Oct 2017 | 0.469999999 | 0.400000006 | 0.810000002 |

| Nov 2017 | 0.550000012 | 0.419999987 | 0.74000001 |

| Dec 2017 | 0.649999976 | 0.330000013 | 0.74000001 |

| Jan 2018 | 0.629999995 | 0.319999993 | 0.819999993 |

| Feb 2018 | 0.689999998 | 0.319999993 | 0.779999971 |

| Mar 2018 | 0.670000017 | 0.360000014 | 1.039999962 |

| Apr 2018 | 0.699999988 | 0.349999994 | 0.939999998 |

| May 2018 | 0.779999971 | 0.360000014 | 0.949999988 |

| Jun 2018 | 0.75999999 | 0.370000005 | 0.910000026 |

| Jul 2018 | 0.819999993 | 0.379999995 | 0.910000026 |

| Aug 2018 | 0.75999999 | 0.389999986 | 0.870000005 |

| Sep 2018 | 0.74000001 | 0.349999994 | 1 |

| Oct 2018 | 0.75999999 | 0.349999994 | 0.850000024 |

| Nov 2018 | 0.790000021 | 0.289999992 | 0.99000001 |

| Dec 2018 | 0.560000002 | 0.289999992 | 1.230000019 |

| Jan 2019 | 0.540000021 | 0.300000012 | 1.049999952 |

| Feb 2019 | 0.49000001 | 0.270000011 | 0.970000029 |

| Mar 2019 | 0.610000014 | 0.270000011 | 0.75999999 |

| Apr 2019 | 0.639999986 | 0.310000002 | 0.790000021 |

| May 2019 | 0.540000021 | 0.270000011 | 0.839999974 |

| Jun 2019 | 0.519999981 | 0.280000001 | 0.959999979 |

| Jul 2019 | 0.560000002 | 0.270000011 | 0.939999998 |

| Aug 2019 | 0.629999995 | 0.200000003 | 1.019999981 |

| Sep 2019 | 0.629999995 | 0.200000003 | 0.870000005 |

| Oct 2019 | 0.589999974 | 0.159999996 | 0.959999979 |

| Nov 2019 | 0.589999974 | 0.180000007 | 0.790000021 |

| Dec 2019 | 0.75999999 | 0.189999998 | 0.660000026 |

| Jan 2020 | 0.769999981 | 0.180000007 | 0.769999981 |

| Feb 2020 | 0.720000029 | 0.200000003 | 0.910000026 |

| Mar 2020 | 0.379999995 | 0.200000003 | 1.00999999 |

| Apr 2020 | -0.01 | 0.159999996 | 0.699999988 |

| May 2020 | -0.01 | 0.189999998 | 0.680000007 |

| Jun 2020 | -0.050000001 | 0.270000011 | 0.639999986 |

| Jul 2020 | 0.02 | 0.319999993 | 0.720000029 |

| Aug 2020 | 0.039999999 | 0.469999999 | 0.779999971 |

| Sep 2020 | 0.170000002 | 0.5 | 0.74000001 |

| Oct 2020 | 0.109999999 | 0.600000024 | 0.600000024 |

| Nov 2020 | 0.07 | 0.600000024 | 0.649999976 |

| Dec 2020 | 0.090000004 | 0.769999981 | 0.569999993 |

| Jan 2021 | 0.219999999 | 0.769999981 | 0.560000002 |

| Feb 2021 | 0.209999993 | 0.939999998 | 0.409999996 |

| Mar 2021 | 0.709999979 | 1.029999971 | 0.370000005 |

| Apr 2021 | 1.200000048 | 1.110000014 | 0.910000026 |

| May 2021 | 1.49000001 | 1.159999967 | 1 |

| Jun 2021 | 1.5 | 1.120000005 | 1.330000043 |

| Jul 2021 | 1.49000001 | 1.070000052 | 1.440000057 |

| Aug 2021 | 1.49000001 | 0.930000007 | 1.580000043 |

| Sep 2021 | 1.340000033 | 0.949999988 | 1.74000001 |

| Oct 2021 | 1.600000024 | 0.970000029 | 1.830000043 |

| Nov 2021 | 1.629999995 | 1.179999948 | 2.069999933 |

| Dec 2021 | 1.620000005 | 1.120000005 | 2.339999914 |

| Jan 2022 | 1.5 | 1.190000057 | 2.529999971 |

| Feb 2022 | 1.700000048 | 1.100000024 | 2.599999905 |

| Mar 2022 | 1.659999967 | 0.99000001 | 2.690000057 |

| Apr 2022 | 1.570000052 | 0.949999988 | 2.470000029 |

| May 2022 | 1.450000048 | 0.939999998 | 2.450000048 |

| Jun 2022 | 1.639999986 | 1.070000052 | 2.25999999 |

| Jul 2022 | 1.629999995 | 1.090000033 | 1.909999967 |

| Aug 2022 | 1.75 | 1.200000048 | 1.899999976 |

| Sep 2022 | 1.970000029 | 1.210000038 | 1.919999957 |

| Oct 2022 | 1.879999995 | 1.299999952 | 1.730000019 |

Note: Decomposition based on work of Shapiro (2022).

Source: “Supply and Demand Driven PCE Inflation” page from the San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank (2022).

Shapiro’s technique for decomposing demand versus supply drivers of inflation might stumble on one potentially important issue—changes in the elasticity of price changes with respect to demand shocks. Take the example of an industry that has seen a very large price increase relative to trend but has seen steady growth in output. Under the Shapiro (2022) decomposition, this would qualify as the source of inflation in the sector being “ambiguous.” But this could easily be a supply issue. If during normal times a mild uptick in demand (a percentage point or two above trend) led to tame price growth, but since the pandemic this mild uptick was associated with very large price increases, this could well actually be a signal that it is supply-side factors that are binding. Further, even for sectors that are characterized as demand- or supply- driven, if the price change associated with any demand or supply mismatch (regardless of which side initially caused it) is greater than it was in the past, this could signal that sectoral frictions—not just macroeconomic factors—are causing the rise of inflation.

On the issue of the interpretation of the results, identifying a given inflationary episode as being driven by “demand” or “supply” can sometimes be akin to asking which blade of the scissors cuts the paper. As Larry Summers put it (fairly enough):

I think it restates what I think is a bit of a popular confusion in the following sense—supply is what it is. Monetary policy can’t change it. Fiscal policy can’t change it, except in the long-run. And so given what supply is, it’s the task of demand to balance supply. And if demand is greater than supply, then you’re going to have excess inflation and you’re going to have the problems of financial excess.

So the job of the demand managers, principally the Fed, is to judge what supply is and calibrate appropriately. It’s not an excuse for inflation to blame it on supply. It’s a reality in the environment that you have to deal with. And so the job is to look for measures of overheating, and when you see measures of overheating, to apply restraint. (Klein 2022)

Real-time estimates of actual and potential GDP don’t look particularly inflationary

Summers’s point that attributing the recent rise in inflation to “demand” or “supply” does not end the debate about the role of excess macroeconomic stimulus in driving today’s inflation is well taken. However, his claim that “supply is what it is” simplifies far too much. The most obvious disruption to potential output (or aggregate supply) in the wake of the COVID-19 shock was the 2.5% decline in labor force participation between February 2020 and the end of 2020. But should policymakers really have looked at this decline and just thought “it is what it is” and pulled back demand growth to match this? Or, instead, was the decline in labor force participation (which fell 3.5% in a single month in April 2020) better seen as a mostly temporary economic casualty of the pandemic that would eventually heal?

So, in some sense it is true that categorizing some inflationary shocks as “supply-driven” does not map perfectly onto a recommendation to keep demand policy stable. But the larger claim that inflation is ipso facto evidence of aggregate demand overshooting supply and hence requires contractionary macroeconomic policy does not follow.

We can get some sense of how much the aggregate levels of demand and supply have shifted relative to pre-pandemic trends using data on GDP and potential output. At the end of 2019, the Congressional Budget Office made projections of both of these variables for the coming years while forecasting little to no change in inflation (or interest rates). The Summers argument above is that either GDP began rising faster than forecast in 2019 (due to excessively expansionary fiscal policy) or that potential output shrank, with either influence (or both influences) leading to a positive “output gap” that drove up inflationary pressures.

Figure F shows real GDP and potential output, both as ratios to what CBO projected they would be before the pandemic. For the measure of potential output, we allow developments since the pandemic to affect the CBO projection. Specifically, we reduce the labor input into potential output by assuming that the decline in the labor force participation rate is driven solely by supply-side factors.2

We also account for changing capital services input and total factor productivity growth relative to CBO projections. For capital services, we construct a measure of growth of the aggregate capital stock that accounts for the nonresidential fixed investment (NRFI) that has occurred since the pandemic and we compare this against CBO projections of capital services input growth. For total factor productivity, we employ the utilization-adjusted measure of total factor productivity growth compiled by John Fernald (2023) and compare that with the CBO forecast.

As can be seen in Figure F, potential output fell sharply (not as sharply as GDP, but still noticeably) in the immediate post-pandemic shock period. As of the third quarter of 2022, it still remained a bit under 2% below what CBO forecast it would be in that quarter. GDP fell very sharply in the pandemic recession, but by the third quarter of 2022 sat roughly 1% beneath what CBO forecast it would be before the pandemic struck.

Output has likely not surged above its potential level post pandemic shock: Adjusted measures of potential GDP and actual GDP, both relative to pre-pandemic CBO forecasts

| Adjusted CBO est. of potential GDP, January 2020 | Actual GDP | |

|---|---|---|

| 2019Q4 | 100.0% | 99.9% |

| 2020Q1 | 100.8% | 98.3% |

| 2020Q2 | 97.7% | 89.4% |

| 2020Q3 | 98.2% | 95.9% |

| 2020Q4 | 96.7% | 96.3% |

| 2021Q1 | 98.0% | 97.3% |

| 2021Q2 | 97.7% | 98.5% |

| 2021Q3 | 98.1% | 98.8% |

| 2021Q4 | 98.4% | 100.0% |

| 2022Q1 | 100.2% | 99.2% |

| 2022Q2 | 98.6% | 98.7% |

| 2022Q3 | 98.2% | 98.9% |

Note: Adjustments to potential GDP as described in text.

Sources: The potential GDP baseline and GDP forecasts are taken from Congressional Budget Office (2021). Actual GDP is taken from Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA).

There was a period of time during 2021 when GDP rose above our adjusted measures of potential output for a stretch. Over the five quarters from the end of 2020 to the end of 2021, the cumulative positive output gap (GDP exceeding potential output) was 5.8%, with an average gap of around 1.2% in each quarter.

That GDP exceeded potential output as inflation rose gives some plausibility to claims that macroeconomic overheating contributed to the recent inflationary spike, but the magnitude of the spike makes it highly unlikely that this overheating played a starring role. There is a well-established literature on how much each 1 percentage point positive output gap should be expected to drive up the inflation rate. These estimates do not exceed 0.5% and cluster more tightly around 0.3% or even lower. This implies that the 1.2% average output gap in that five-quarter stretch should be expected to raise subsequent inflation by roughly 0.4–0.6%, or by about a tenth of its actual acceleration over this period.

A historical example might help make this clearer. According to CBO estimates, the U.S. economy ran a cumulative positive output gap of over 17% of potential output, with an average gap of 1.2%, over the period from 1997 to 2000. This was the same average gap as that seen in 2021, but sustained for four times as long. Yet there was no inflationary increase at all during this period. In short, running the economy this “hot” for a year is not supposed to yield anywhere near the degree of inflation that we have witnessed since the middle of 2021.

Figure G shows the history of output gaps since 1995. For the last two years, we show the gap with an unadjusted measure of potential output from CBO’s last pre-pandemic projection, plus the gap with our adjusted measure of potential output. Even with our adjusted measure, which accounts for pandemic damage to the economy’s aggregate potential output, the positive output gaps of the past 18 months are utterly unremarkable relative to recent U.S. economic history—a history that saw no similar inflationary spike.

Positive 2021 output gap is unremarkable in recent history: Output gaps (% of GDP) since 1995, including adjusted output gap for 2021–2022

| Output gap, adjusted | Output gap, unadjusted | |

|---|---|---|

| 1995Q1 | -1.037442674 | |

| 1995Q2 | -1.417944987 | |

| 1995Q3 | -1.253764142 | |

| 1995Q4 | -1.267621768 | |

| 1996Q1 | -1.218840757 | |

| 1996Q2 | -0.30597483 | |

| 1996Q3 | -0.193508223 | |

| 1996Q4 | 0.015040705 | |

| 1997Q1 | -0.207254381 | |

| 1997Q2 | 0.541406779 | |

| 1997Q3 | 0.848909855 | |

| 1997Q4 | 0.740745752 | |

| 1998Q1 | 0.753957453 | |

| 1998Q2 | 0.671584645 | |

| 1998Q3 | 0.907080142 | |

| 1998Q4 | 1.498258603 | |

| 1999Q1 | 1.407574806 | |

| 1999Q2 | 1.205981182 | |

| 1999Q3 | 1.490939149 | |

| 1999Q4 | 2.09073296 | |

| 2000Q1 | 1.403664348 | |

| 2000Q2 | 2.213327853 | |

| 2000Q3 | 1.336220186 | |

| 2000Q4 | 1.013814946 | |

| 2001Q1 | -0.17651419 | |

| 2001Q2 | -0.367073431 | |

| 2001Q3 | -1.519140107 | |

| 2001Q4 | -1.953546467 | |

| 2002Q1 | -1.811436526 | |

| 2002Q2 | -1.851007007 | |

| 2002Q3 | -2.081713335 | |

| 2002Q4 | -2.564721809 | |

| 2003Q1 | -2.66607767 | |

| 2003Q2 | -2.404946463 | |

| 2003Q3 | -1.389227218 | |

| 2003Q4 | -0.86926817 | |

| 2004Q1 | -0.928038684 | |

| 2004Q2 | -0.789297985 | |

| 2004Q3 | -0.501182803 | |

| 2004Q4 | -0.136371387 | |

| 2005Q1 | 0.332489649 | |

| 2005Q2 | 0.200815071 | |

| 2005Q3 | 0.379377318 | |

| 2005Q4 | 0.356940212 | |

| 2006Q1 | 1.130602179 | |

| 2006Q2 | 0.814758487 | |

| 2006Q3 | 0.429248749 | |

| 2006Q4 | 0.762090719 | |

| 2007Q1 | 0.54801544 | |

| 2007Q2 | 0.678655708 | |

| 2007Q3 | 0.771103249 | |

| 2007Q4 | 0.876392638 | |

| 2008Q1 | -0.031770238 | |

| 2008Q2 | 0.062268994 | |

| 2008Q3 | -0.914045502 | |

| 2008Q4 | -3.486071828 | |

| 2009Q1 | -4.979094406 | |

| 2009Q2 | -5.479377457 | |

| 2009Q3 | -5.455786055 | |

| 2009Q4 | -4.755715265 | |

| 2010Q1 | -4.590521875 | |

| 2010Q2 | -3.987322966 | |

| 2010Q3 | -3.581543154 | |

| 2010Q4 | -3.429040795 | |

| 2011Q1 | -4.020298733 | |

| 2011Q2 | -3.742455073 | |

| 2011Q3 | -4.163170099 | |

| 2011Q4 | -3.483241686 | |

| 2012Q1 | -3.098823814 | |

| 2012Q2 | -3.072610555 | |

| 2012Q3 | -3.325044436 | |

| 2012Q4 | -3.645040485 | |

| 2013Q1 | -3.243102357 | |

| 2013Q2 | -3.545280881 | |

| 2013Q3 | -3.221571848 | |

| 2013Q4 | -2.978336665 | |

| 2014Q1 | -3.762823871 | |

| 2014Q2 | -2.977166383 | |

| 2014Q3 | -2.306752966 | |

| 2014Q4 | -2.329227621 | |

| 2015Q1 | -1.996928446 | |

| 2015Q2 | -1.889443822 | |

| 2015Q3 | -2.027380247 | |

| 2015Q4 | -2.329516612 | |

| 2016Q1 | -2.194154532 | |

| 2016Q2 | -2.33092847 | |

| 2016Q3 | -2.170039754 | |

| 2016Q4 | -2.106614267 | |

| 2017Q1 | -2.10915828 | |

| 2017Q2 | -2.03636394 | |

| 2017Q3 | -1.657360043 | |

| 2017Q4 | -1.111337256 | |

| 2018Q1 | -0.878552423 | |

| 2018Q2 | -0.650842836 | |

| 2018Q3 | -0.406639899 | |

| 2018Q4 | -0.697743417 | |

| 2019Q1 | -0.629675979 | |

| 2019Q2 | -0.434271331 | |

| 2019Q3 | -0.023450459 | |

| 2019Q4 | -0.051535901 | |

| 2020Q1 | -1.679857519 | -1.860602484 |

| 2020Q2 | -10.41743765 | -7.776585183 |

| 2020Q3 | -3.765909602 | -1.546344629 |

| 2020Q4 | -3.246589566 | 0.393500667 |

| 2021Q1 | -2.180082048 | 0.151483956 |

| 2021Q2 | -0.956479479 | 1.59083981 |

| 2021Q3 | -0.757843738 | 1.382575058 |

| 2021Q4 | 0.461432469 | 2.281207018 |

| 2022Q1 | -0.406699174 | -0.513727689 |

| 2022Q2 | -1.024362749 | 0.543082553 |

| 2022Q3 | -0.872460261 | 1.11867539 |

Sources: Data taken from Congressional Budget Office (2021) and Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA).

Tight labor markets usually boost—not reduce—labor’s relative bargaining power

Finally, we highlight some evidence from the labor market to assess the claim that a straightforward story of macroeconomic overheating is at the core of recent inflation. Generally, claims that inflation accelerations are driven by an excess of aggregate demand over potential output rest on theories of labor market overheating. As aggregate demand exceeds potential output, unemployment falls. In turn, this boosts workers’ bargaining position with employers and accelerates wage growth. If nominal wage growth begins exceeding price inflation, this leads to a rise in labor’s share of income.

The general logic that lower rates of unemployment boost nominal wage growth more than price inflation is sound and supported by empirical evidence. As the recent inflationary episode began in 2021, it was often accompanied by stories of labor shortages in many sectors. This led far too many to assume that wage pressures were pushing up price growth, and the simple story of the labor market overheating due to a macroeconomic excess of aggregate demand over potential output gained credence.

The first bit of evidence against the claim that rolling labor shortages across sectors led to prices rising can be seen in Figure H. This graph shows the acceleration in price inflation and the acceleration in nominal wage growth across 61 industries. It measures acceleration of prices and wages as their annualized growth rate between the second quarter of 2020 and the third quarter of 2022 relative to the annualized growth rate that prevailed on average between 2018 and 2019. There is no discernible correlation at all between these measures.

Industry price inflation not driven by rolling labor shortages: One-year acceleration of inflation and nominal wage growth by industry in September 2022

| date | 1-year change in wages | 1-year change in prices |

|---|---|---|

| 2022q2 | 0.1268338% | 0.0230537% |

| 2022q2 | 0.1245117 | 0.0651971 |

| 2022q2 | 0.1096804 | 0.1264156 |

| 2022q2 | 0.1003991 | 0.0259661 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0991156 | 0.1033432 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0969601 | 0.0559718 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0916344 | 0.1778477 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0900257 | 0.0089109 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0845733 | 0.1346681 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0788986 | 0.0216826 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0783661 | 0.1933899 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0744892 | -0.1681365 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0741051 | 0.0422949 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0726174 | -0.0779248 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0720981 | 0.1865076 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0679267 | 0.037667 |

| 2022q2 | 0.067722 | 0.0288282 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0670871 | 0.0790173 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0643922 | 0.0205015 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0603795 | 0.0738291 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0581729 | 0.2302468 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0581624 | 1.571569 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0579678 | 0.0183528 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0577908 | 0.2409101 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0562284 | 0.1927279 |

| 2022q2 | 0.056197 | 0.1326708 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0560012 | 0.0655703 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0548044 | 0.0956108 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0543616 | 0.0422047 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0538076 | 0.1594304 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0535776 | 0.1869677 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0514923 | 0.138399 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0472634 | 0.2707055 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0450574 | -0.0537838 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0444742 | 0.1343548 |

| 2022q2 | 0.04378 | 0.042727 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0420794 | 0.1839621 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0412392 | 0.0947621 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0410261 | 0.1483489 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0409108 | 0.1354458 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0406292 | -0.0298556 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0395538 | 0.0240901 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0394657 | 0.266773 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0363253 | 0.1499694 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0355256 | -0.076805 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0332553 | 0.0607655 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0243052 | 1.300836 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0135722 | 0.0266431 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0106534 | 0.2336368 |

| 2022q2 | 0.0081077 | 0.0399025 |

| 2022q2 | -0.0013241 | 0.0166427 |

| 2022q2 | -0.0103535 | -0.0151664 |

| 2022q2 | -0.0124126 | -0.0112901 |

| 2022q2 | -0.0160883 | 0.0316972 |

| 2022q2 | -0.0231058 | 0.1023001 |

| 2022q2 | -0.031784 | 0.213711 |

| 2022q2 | -0.0602599 | 0.1961474 |

Note: Both inflation and wage acceleration defined as year-over-year change in September 2022, minus average rates in 2018–2019.

Sources: Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) GDP-by-Industry series and Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Current Employment Statistics (CES).

Moreover, while nominal wage growth did accelerate in 2021, it never exceeded price inflation. This means that real (inflation-adjusted) wages have been falling since early 2021. This also led to a pronounced fall in the labor share of income in the corporate sector, which has largely not recovered from its post-pandemic low. It seems odd that a labor shortage could somehow be the source of inflation given this data—it is rare for services in short supply to command less and less income growth on a per-unit basis.

This fall in real wages and the labor share of income is absolutely not the norm for the U.S. economy as it “heats up” in recoveries. This fact has been missed by far too many commenters. Many have made implicit claims that a sharp fall in the labor share of income and real wages is the norm for an economy with positive output gaps. Rampell (2022), for example, writes:

The greedflationists argue that something fishy is afoot because companies are not merely “passing along” their higher costs; their profit margins are expanding, too. But this is exactly what you’d expect when flush customers are buying more stuff and willing to pay whatever’s necessary to get what they want. Prices and profits rise.

Read “flush customers willing to pay whatever’s necessary to get what they want” as “high levels of aggregate demand relative to potential output.” Is it really true that historical experience would lead one to expect that high levels of aggregate demand lead to prices and profits rising?

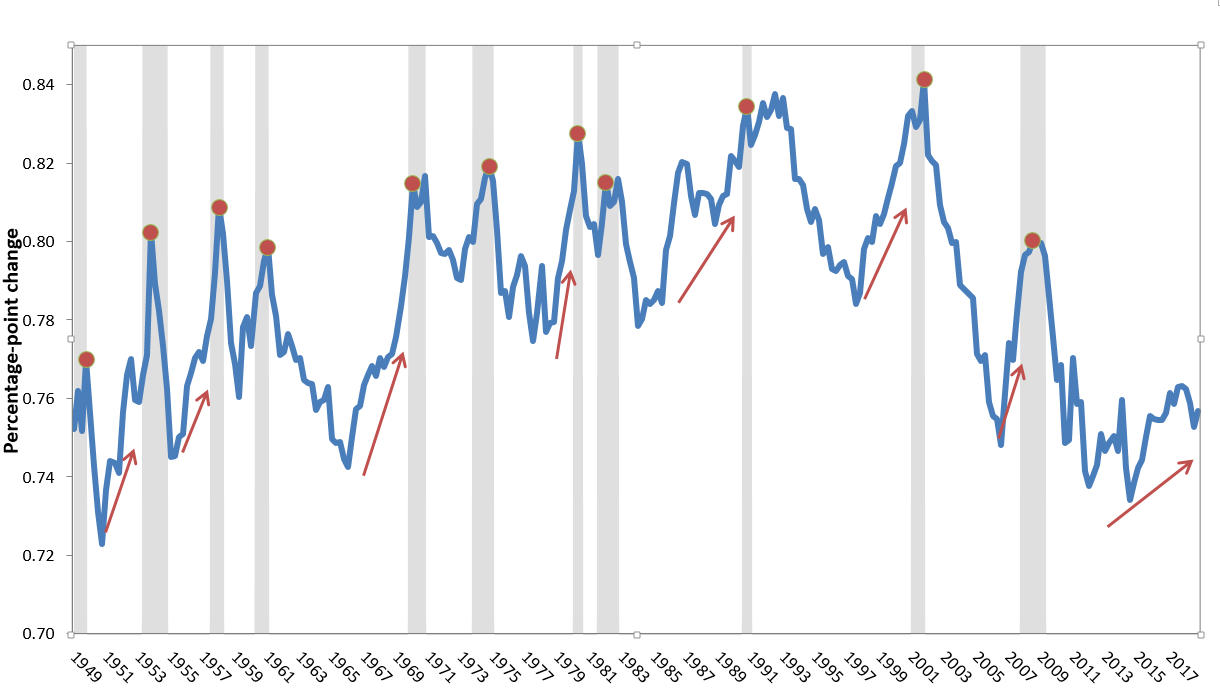

Not really. Figure I shows the labor share of income in the corporate sector since 1949. The cyclical dynamics of the labor share are slightly complicated: The labor share is not “countercyclical” as it is sometimes described. It does rise sharply during outright recessions, as more volatile profits decline sharply during economic downturns. But in early recoveries with unemployment still high, the labor share universally falls sharply. Then, in mid-recovery as unemployment starts to approach (or fall beneath) pre-recession lows, the labor share begins to rise as unemployment falls—or, as the economy “heats up.”

Figure I also shows variability and potential decade-specific trends in labor’s share. This explains why a simple scatterplot of the relationship between the change in labor’s share of income and the unemployment gap is very noisy, with only a mild (if statistically significant) downward correlation, which indicates that low unemployment gaps (signifying tight labor markets) are weakly associated with an increased labor share.

After we control for decade-specific dummy variables and decade-specific trends, this relationship dramatically strengthens, as shown in Figure J. The figure shows the coefficient on the unemployment gap from a regression of the change in the labor share on the unemployment gap, plus decade-specific dummy variables, decade-specific trends, and productivity growth. It shows this regression for all periods in our data (quarterly data from 1949 to 2018), as well as periods when the unemployment gap is greater than 1, less than or equal to 1, greater than 0, and less than or equal to 0. An unemployment gap of 0 or below indicates a tight labor market with actual unemployment either equal to or less than estimates of the natural rate. An unemployment gap of 1 or below indicates an economy operating below full employment but within shouting distance of it. An unemployment gap of above 1 indicates an unhealthy labor market.

What does this tell us? That it is extremely unusual for labor’s share of income to fall (or even stagnate) even as unemployment falls beneath 5%: Higher profits are not the expected signature of an overheating economy. In this sense, the recent low levels of labor’s share and the poor performance of real wages are signs that the current economy does not look anything like a typically overheating economy.

In tight labor markets, the labor share of income rises: Change in labor’s share of income per 1 percentage point decline in the unemployment gap, overall and by unemployment gap values

| Samples | |

|---|---|

| Overall | 0.16% |

| >1 | 0.08% |

| ≤1 | 0.312% |

| >0 | 0.137% |

| ≤0 | 0.47% |

Notes: The unemployment gap is the actual unemployment rate minus the estimate of the natural rate of unemployment. Bars represent the regression coefficient on the unemployment gap from a regression, with the change in the labor share of income as the dependent variable. Controls include productivity growth and the four-quarter change in the unemployment rate; dummy variables for the business cycles of the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, and for the 2001–2007 business cycle; and business cycle–specific trends for each of those time periods. An asterisk indicates the coefficient is not statistically significant at conventional levels.

Sources: Author’s analysis of data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA), unemployment rates from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), and estimates of the natural rate of unemployment from the Congressional Budget Office (2019).

If not macroeconomic imbalances, then what? Sectoral shocks and their ripples

If the driver of recent inflation was not large macroeconomic imbalances, then what was it? Put simply, extraordinarily sharp sectoral shocks and the large ripples these shocks generated drove recent inflation. Tobin (1972) provides probably the best description of how large sectoral shocks can cause persistent inflation. Key to his reasoning is the empirical finding that nominal wages are extremely rigid downward. Given this downward nominal wage rigidity, adjusting to sectoral shocks to demand and supply will always require inflation (rising nominal wages in expanding sectors) rather than deflation or neutral aggregate wage and price growth (i.e., rising or flat nominal wages in expanding sectors matched by falling nominal wages in contracting sectors). These insights are profound enough to quote at length:

The overlap of vacancies and unemployment—say, the sum of the two for any given difference between them—is a measure of the heterogeneity or dispersion of individual markets. The amount of dispersion depends directly on the size of those shocks of demand and technology that keep markets in perpetual disequilibrium, and inversely on the responsive mobility of labor. The one increases, the other diminishes the frictional component of unemployment, that is, the number of unfilled vacancies coexisting with any given unemployment rate. A central assumption of the theory is that the functions relating wage change to excess demand or supply are non-linear, specifically that unemployment retards money wages less than vacancies accelerate them. Non-linearity in the response of wages to excess demand has several important implications.

First, it helps to explain the characteristic observed curvature of the Phillips curve. Each successive increment of unemployment has less effect in reducing the rate of inflation. Linear wage response, on the other hand, would mean a linear Phillips relation. Second, given the overall state of aggregate demand, economy-wide vacancies less unemployment, wage inflation will be greater the larger the variance among markets in excess demand and supply. As a number of recent empirical studies have confirmed (see George Perry and Charles Schultze), dispersion is inflationary. Of course, the rate of wage inflation will depend not only on the overall dispersion of excess demands and supplies across markets but also on the particular markets where the excess supplies and demands happen to fall. An unlucky random drawing might put the excess demands in highly responsive markets and the excess supplies in especially unresponsive ones. Third, the nonlinearity is an explanation of inflationary bias, in the following sense. Even when aggregate vacancies are at most equal to unemployment, the average disequilibrium component will be positive. Full employment in the sense of equality of vacancies and unemployment is not compatible with price stability. Zero inflation requires unemployment in excess of vacancies. (p. 10)

If Tobin is right that “dispersion [of sectoral shocks] is inflationary,” then the mammoth response of inflation to the COVID-19 shock becomes very easy to understand—this pandemic effect was the mother of all shocks to sectoral dispersion. Further, specific features of the 2021 economy meant that any shock to sectoral imbalances would have led to large ripple effects, mostly through shocks’ effects on the labor market, which saw nominal wages respond to nonlabor cost shocks and support inflation to an unexpected degree.

These “ripple” effects stem in part from the distributional conflict resulting from inflationary shocks as various economic groups try to protect their real incomes. As Ros (1989) puts it: “A common form of [conflict inflation] arises when the real wage reflecting the balance of power in the labour market, and expressing the expectations created in wage bargains, is not validated by the real wage implied by price formation in other markets” (p. 8). So, if a shock to the cost of nonlabor inputs (say lumber used in home building and chips used in automobile production) pushes up prices, workers might respond by bargaining for higher nominal wages to protect their living standards. In turn, firms may accommodate their own workers’ nominal wage demands (or at least some of them) yet maintain or even expand profit margins to protect their own incomes.

This conflicting-claims view of U.S. inflation is not well known or often wrestled with in most macroeconomic commentary. There’s one pretty good reason for this—for decades, it has largely not been an issue, as a number of policy changes have so disempowered U.S. workers that their efforts to protect real incomes from any shocks have been limited enough to leave almost no mark on inflationary dynamics. Ratner and Sim (2022) provide compelling evidence that the extremely low inflation that characterized the 30 years before COVID-19 is likely largely explained by a pronounced shift in bargaining power from workers to firms. Yet in 2021, these conflicting claims on real output following large exogenous shocks led to the large and persistent ripple effects in inflation.

What are the analytical and policy stakes in distinguishing between inflation driven by macroeconomic overheating (imbalances in the level of aggregate demand and potential output) versus a “shocks and ripples” theory? Even if they are large, as long as the ripple effects following inflationary shocks dampen rather than amplify the initial inflationary shock, then macroeconomic policymakers should not have to pursue aggressively contractionary policies to rein inflation back in. This is not simply tautological—sometimes shocks really do set off ripple effects that amplify the initial impulse and need some external force (looser labor markets in the current context) to provide dampening. But so long as wage growth lags behind price inflation, the ripple effects—large as they might be—will steadily dampen the initial shocks and return inflation to more normal levels over time, even absent any effort to engineer looser labor markets.

Below we more sharply distinguish just what the economic shocks caused by COVID-19 and the Russian invasion of Ukraine were. We also outline how the ripple effects kept inflation more persistent than what many forecast going into this episode, though the effects still look set to fade as long as the shocks stop coming.

What were the shocks?

The main shocks to the U.S. economy from the pandemic and war were the economic distortions that they created in both demand and supply patterns. On demand, the composition of GDP shifted with a historically rapid reallocation in spending and demand away from services and government and into durable goods consumption and residential investment. On the supply side, the pandemic and war contributed to massive supply chain snarls, further heightened by port shutdowns and the global spike in raw material, energy, and commodities prices.

Demand shocks: consumption patterns and the underappreciated role of housing

The shift in demand patterns away from face-to-face, high-contact services (such as gyms, movie theaters, travel) and toward durable goods and residences (cars and houses) was clearly a consequence of the pandemic, and it has shown remarkable persistence. Figure K displays the shock to the composition of demand in historical context from 1980 through the present. We examine the share of GDP made up of durables and residential investment and demonstrate how it has changed relative to the average of the previous two years. Clearly, the onset of the pandemic led to a historically unprecedented jump in the share of durable goods consumption and residential investment (the last rise, though at a much slower rate, can be seen in the early 2000s). In recent years, the share of durables consumption and residential investment has moved a bit closer to normal, but it remains at a high level relative to historical averages. (In Figure K, one can see that the level of demand as of 2022 Q3 was roughly in line with what it has been for the past two years—i.e., the line hovers near zero—and these past two years have been dominated by the COVID-19 patterns of spending.) This historically sharp swing in demand across sectors is certainly a large enough shock to explain the beginning of the recent inflationary episode.

The swing toward durable goods consumption and away from face-to-face services is intuitive to understand (the classic example being the substitution of Peloton purchases for gym memberships). However, the boost to housing demand driven by the pandemic is even better documented by the data. Apparently, the prevalence of remote work led to a large positive shock in housing demand as more people worked from home, first out of necessity of social distancing for public health, but then (for many) out of choice. Working from home in turn inspired demand for more space and smaller households, leading to a large surge in new purchases and household formation that ran far ahead of population growth for 2021.

Pandemic led to sharp sectoral swings in demand: Change in share of GDP accounted for by durable goods and residential investment, 1980–2022

| Change in share of GDP | |

|---|---|

| 1980Q1 | -0.55 |

| 1980Q2 | -1 |

| 1980Q3 | -0.725 |

| 1980Q4 | -1 |

| 1981Q1 | -1 |

| 1981Q2 | -1.175 |

| 1981Q3 | -1.225 |

| 1981Q4 | -1.475 |

| 1982Q1 | -0.95 |

| 1982Q2 | -1.325 |

| 1982Q3 | -1.3 |

| 1982Q4 | -1.1 |

| 1983Q1 | -1.575 |

| 1983Q2 | -1.225 |

| 1983Q3 | -1.1 |

| 1983Q4 | -1 |

| 1984Q1 | -1.075 |

| 1984Q2 | -0.9 |

| 1984Q3 | -1.025 |

| 1984Q4 | -0.775 |

| 1985Q1 | -0.625 |

| 1985Q2 | -0.575 |

| 1985Q3 | -0.6 |

| 1985Q4 | -0.8 |

| 1986Q1 | -0.85 |

| 1986Q2 | -0.975 |

| 1986Q3 | -0.4 |

| 1986Q4 | -0.6 |

| 1987Q1 | -0.9 |

| 1987Q2 | -0.5 |

| 1987Q3 | -0.15 |

| 1987Q4 | -0.75 |

| 1988Q1 | -0.375 |

| 1988Q2 | -0.725 |

| 1988Q3 | -0.775 |

| 1988Q4 | -0.725 |

| 1989Q1 | -0.85 |

| 1989Q2 | -0.775 |

| 1989Q3 | -0.825 |

| 1989Q4 | -0.875 |

| 1990Q1 | -0.7 |

| 1990Q2 | -1.15 |

| 1990Q3 | -0.975 |

| 1990Q4 | -0.875 |

| 1991Q1 | -1.15 |

| 1991Q2 | -1.05 |

| 1991Q3 | -1.225 |

| 1991Q4 | -1.475 |

| 1992Q1 | -1.225 |

| 1992Q2 | -1.4 |

| 1992Q3 | -1.25 |

| 1992Q4 | -1.4 |

| 1993Q1 | -1.4 |

| 1993Q2 | -1.1 |

| 1993Q3 | -1.05 |

| 1993Q4 | -0.85 |

| 1994Q1 | -0.75 |

| 1994Q2 | -0.7 |

| 1994Q3 | -0.325 |

| 1994Q4 | -0.1 |

| 1995Q1 | -0.25 |

| 1995Q2 | -0.175 |

| 1995Q3 | -0.175 |

| 1995Q4 | -0.2 |

| 1996Q1 | -0.125 |

| 1996Q2 | -0.125 |

| 1996Q3 | -0.25 |

| 1996Q4 | -0.3 |

| 1997Q1 | -0.275 |

| 1997Q2 | -0.775 |

| 1997Q3 | -0.7 |

| 1997Q4 | -0.65 |

| 1998Q1 | -0.925 |

| 1998Q2 | -0.575 |

| 1998Q3 | -0.575 |

| 1998Q4 | -0.275 |

| 1999Q1 | -0.375 |

| 1999Q2 | 0.15 |

| 1999Q3 | 0.15 |

| 1999Q4 | 0.175 |

| 2000Q1 | 0.525 |

| 2000Q2 | 0.325 |

| 2000Q3 | 0.525 |

| 2000Q4 | 0.7 |

| 2001Q1 | 0.675 |

| 2001Q2 | 0.5 |

| 2001Q3 | 0.45 |

| 2001Q4 | 0.75 |

| 2002Q1 | 0.3 |

| 2002Q2 | 0.125 |

| 2002Q3 | 0.025 |

| 2002Q4 | -0.25 |

| 2003Q1 | -0.125 |

| 2003Q2 | -0.225 |

| 2003Q3 | -0.025 |

| 2003Q4 | -0.175 |

| 2004Q1 | -0.05 |

| 2004Q2 | -0.1 |

| 2004Q3 | -0.25 |

| 2004Q4 | -0.025 |

| 2005Q1 | -0.35 |

| 2005Q2 | -0.175 |

| 2005Q3 | 0.125 |

| 2005Q4 | -0.175 |

| 2006Q1 | -0.25 |

| 2006Q2 | -0.275 |

| 2006Q3 | -0.175 |

| 2006Q4 | -0.575 |

| 2007Q1 | -0.475 |

| 2007Q2 | -0.5 |

| 2007Q3 | -0.525 |

| 2007Q4 | -0.35 |

| 2008Q1 | -0.55 |

| 2008Q2 | -0.525 |

| 2008Q3 | -0.575 |

| 2008Q4 | -1.975 |

| 2009Q1 | -1.925 |

| 2009Q2 | -1.75 |

| 2009Q3 | -1.05 |

| 2009Q4 | -1.3 |

| 2010Q1 | -1.225 |

| 2010Q2 | -1.225 |

| 2010Q3 | -1.35 |

| 2010Q4 | -1 |

| 2011Q1 | -0.6 |

| 2011Q2 | -0.575 |

| 2011Q3 | -0.175 |

| 2011Q4 | 0.075 |

| 2012Q1 | 0.525 |

| 2012Q2 | 0.4 |

| 2012Q3 | 0.3 |

| 2012Q4 | 0.3 |

| 2013Q1 | 0.25 |

| 2013Q2 | 0.175 |

| 2013Q3 | -0.05 |

| 2013Q4 | -0.175 |

| 2014Q1 | -0.225 |

| 2014Q2 | -0.4 |

| 2014Q3 | -0.575 |

| 2014Q4 | -0.775 |

| 2015Q1 | -1 |

| 2015Q2 | -0.825 |

| 2015Q3 | -0.8 |

| 2015Q4 | -0.85 |

| 2016Q1 | -1.025 |

| 2016Q2 | -0.85 |

| 2016Q3 | -0.85 |

| 2016Q4 | -0.775 |

| 2017Q1 | -0.65 |

| 2017Q2 | -0.75 |

| 2017Q3 | -0.7 |

| 2017Q4 | -0.35 |

| 2018Q1 | -0.425 |

| 2018Q2 | -0.325 |

| 2018Q3 | -0.45 |

| 2018Q4 | -0.4 |

| 2019Q1 | -0.55 |

| 2019Q2 | -0.475 |

| 2019Q3 | -0.425 |

| 2019Q4 | -0.45 |

| 2020Q1 | -0.325 |

| 2020Q2 | 0.875 |

| 2020Q3 | 1.525 |

| 2020Q4 | 1.25 |

| 2021Q1 | 2.25 |

| 2021Q2 | 2.7 |

| 2021Q3 | 2.2 |

| 2021Q4 | 2.2 |

| 2022Q1 | 2.6 |

| 2022Q2 | 2.55 |

| 2022Q3 | 2.4 |

Note: The average annual share of GDP accounted for by durable goods consumption and residential investment lagged 30 months is subtracted from the current quarter.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA).

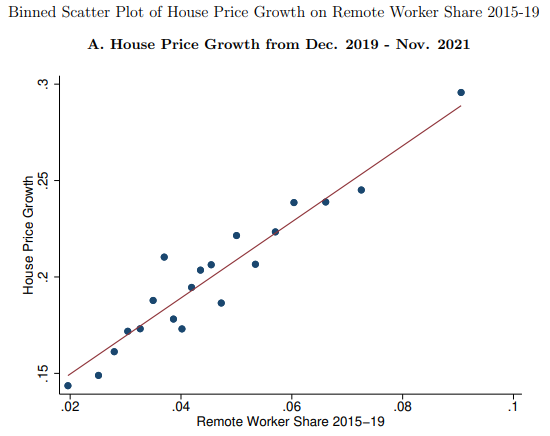

This pandemic shock to housing demand had profound implications for subsequent inflation. Housing is a key component of inflation, making up 40% of core consumption spending in the CPI. Housing prices (including rents) have also increased dramatically since 2019. Figure L shows the tight relationship between remote work and the growth in home prices, as shown in Mondragon and Wieland (2022).

Figure L (taken directly from Mondragon and Wieland 2022) shows a strong positive relationship between home price growth and exposure to remote work, meaning that the areas most exposed to remote work had home price growth twice as high as the areas least exposed. Their model further estimates that remote work raised aggregate home prices by 15.1%, accounting for well over half of the rise in housing prices over that time. Clearly, the pandemic shock to housing demand and subsequent price growth is a crucial component of the 2021 inflation story.

Though housing prices have been high through the pandemic, they seem to have been assigned less blame in the recent inflation episode compared with the overheating or fiscal over-stimulus arguments. Why has housing been such an underrated contributor to high inflation in economic policymaking discussions? Mostly because official measures of housing costs were one of the last components of inflation to noticeably accelerate. The measurement of housing prices is one of the most backward-looking price indicators, with increases in new rents and home prices in many industry data sources only visibly pushing up costs in the CPI 6–12 months later.

Given this lag and the backward-looking nature of housing measurement, a shock to housing demand generally does not manifest in an increase in housing prices and rents until the following year. This means that many policymakers and economic commentators were unable to track the extent of price changes as they occurred. Figure M shows the correlation between annual growth in the Case-Shiller home price index, lagged one year, and annual growth in the shelter component of the CPI since 1989.

This lag between home price changes and when they are reflected in falling shelter in the CPI meant that the 2021 positive shock to housing demand stemming from the pandemic only pushed up official measures of inflation later in 2022. However, it is also important to note that the reverse dynamic is likely to characterize rental prices going forward—substantial weakness in early-warning measures of rental prices will show up only in a slower rate of CPI growth with a significant lag.

Housing disinflation follows industry measures with a long—but reliable—lag: Case-Shiller index of home prices and the shelter component of the consumer price index, lagged one year

| date | Case-Shller index | Consumer Price Index |

|---|---|---|

| 1980-01-01 | 12.8% | 13.7% |

| 1980-02-01 | 12.1% | 12.4% |

| 1980-03-01 | 11.6% | 11.0% |

| 1980-04-01 | 11.1% | 10.1% |

| 1980-05-01 | 10.5% | 10.1% |

| 1980-06-01 | 9.8% | 9.2% |

| 1980-07-01 | 9.3% | 12.5% |

| 1980-08-01 | 8.9% | 13.6% |

| 1980-09-01 | 8.5% | 14.5% |

| 1980-10-01 | 7.9% | 12.5% |

| 1980-11-01 | 7.6% | 11.0% |

| 1980-12-01 | 7.4% | 9.9% |

| 1981-01-01 | 7.2% | 9.4% |

| 1981-02-01 | 7.0% | 9.7% |

| 1981-03-01 | 6.7% | 8.7% |

| 1981-04-01 | 6.7% | 9.2% |

| 1981-05-01 | 6.7% | 9.3% |

| 1981-06-01 | 6.7% | 9.0% |

| 1981-07-01 | 6.5% | 7.7% |

| 1981-08-01 | 6.4% | 6.9% |

| 1981-09-01 | 6.1% | 4.8% |

| 1981-10-01 | 5.8% | 4.9% |

| 1981-11-01 | 5.4% | 4.1% |

| 1981-12-01 | 5.1% | 2.3% |

| 1982-01-01 | 4.8% | 3.0% |

| 1982-02-01 | 4.6% | 3.0% |

| 1982-03-01 | 3.9% | 3.6% |

| 1982-04-01 | 3.1% | 3.3% |

| 1982-05-01 | 2.5% | 2.0% |

| 1982-06-01 | 1.9% | 1.0% |

| 1982-07-01 | 1.3% | 0.9% |

| 1982-08-01 | 0.8% | 0.7% |

| 1982-09-01 | 0.6% | 1.7% |

| 1982-10-01 | 0.5% | 1.9% |

| 1982-11-01 | 0.5% | 2.9% |

| 1982-12-01 | 0.6% | 4.8% |

| 1983-01-01 | 0.8% | 4.3% |

| 1983-02-01 | 1.2% | 4.4% |

| 1983-03-01 | 1.7% | 4.8% |

| 1983-04-01 | 2.1% | 4.7% |

| 1983-05-01 | 2.4% | 4.6% |

| 1983-06-01 | 3.0% | 4.6% |

| 1983-07-01 | 3.6% | 4.9% |

| 1983-08-01 | 4.1% | 5.1% |

| 1983-09-01 | 4.3% | 5.0% |

| 1983-10-01 | 4.5% | 5.2% |

| 1983-11-01 | 4.6% | 5.1% |

| 1983-12-01 | 4.7% | 5.2% |

| 1984-01-01 | 4.7% | 5.2% |

| 1984-02-01 | 4.5% | 5.5% |

| 1984-03-01 | 4.5% | 5.4% |

| 1984-04-01 | 4.6% | 5.0% |

| 1984-05-01 | 4.7% | 5.8% |

| 1984-06-01 | 4.8% | 5.8% |

| 1984-07-01 | 4.8% | 5.6% |

| 1984-08-01 | 4.8% | 5.8% |

| 1984-09-01 | 4.9% | 5.6% |

| 1984-10-01 | 4.9% | 5.7% |

| 1984-11-01 | 4.7% | 6.1% |

| 1984-12-01 | 4.7% | 5.9% |

| 1985-01-01 | 4.7% | 6.1% |

| 1985-02-01 | 4.9% | 5.7% |

| 1985-03-01 | 5.0% | 6.0% |

| 1985-04-01 | 5.1% | 6.4% |

| 1985-05-01 | 5.3% | 5.5% |

| 1985-06-01 | 5.4% | 5.5% |

| 1985-07-01 | 5.6% | 5.3% |

| 1985-08-01 | 5.8% | 5.0% |

| 1985-09-01 | 6.2% | 5.3% |

| 1985-10-01 | 6.6% | 5.4% |

| 1985-11-01 | 7.1% | 4.9% |

| 1985-12-01 | 7.5% | 4.8% |

| 1986-01-01 | 7.7% | 4.8% |

| 1986-02-01 | 7.9% | 4.9% |

| 1986-03-01 | 8.1% | 4.5% |

| 1986-04-01 | 8.4% | 4.6% |

| 1986-05-01 | 8.6% | 4.8% |

| 1986-06-01 | 8.8% | 4.7% |

| 1986-07-01 | 9.1% | 4.5% |

| 1986-08-01 | 9.3% | 4.8% |

| 1986-09-01 | 9.4% | 4.7% |

| 1986-10-01 | 9.4% | 4.8% |

| 1986-11-01 | 9.4% | 4.8% |

| 1986-12-01 | 9.6% | 5.1% |

| 1987-01-01 | 9.6% | 5.1% |

| 1987-02-01 | 9.6% | 5.0% |

| 1987-03-01 | 9.4% | 5.0% |

| 1987-04-01 | 9.2% | 4.7% |

| 1987-05-01 | 9.2% | 4.6% |

| 1987-06-01 | 9.2% | 4.8% |

| 1987-07-01 | 9.0% | 5.0% |

| 1987-08-01 | 8.9% | 4.8% |

| 1987-09-01 | 8.6% | 4.8% |

| 1987-10-01 | 8.5% | 4.5% |

| 1987-11-01 | 8.3% | 4.7% |

| 1987-12-01 | 7.8% | 4.4% |

| 1988-01-01 | 7.6% | 4.2% |

| 1988-02-01 | 7.5% | 4.2% |

| 1988-03-01 | 7.5% | 4.4% |

| 1988-04-01 | 7.4% | 4.3% |

| 1988-05-01 | 7.4% | 4.5% |

| 1988-06-01 | 7.3% | 4.4% |

| 1988-07-01 | 7.3% | 4.7% |

| 1988-08-01 | 7.3% | 4.6% |

| 1988-09-01 | 7.3% | 4.4% |

| 1988-10-01 | 7.2% | 4.8% |

| 1988-11-01 | 7.3% | 4.8% |

| 1988-12-01 | 7.2% | 4.9% |

| 1989-01-01 | 7.3% | 5.0% |

| 1989-02-01 | 7.3% | 4.8% |

| 1989-03-01 | 7.3% | 5.0% |

| 1989-04-01 | 7.3% | 5.2% |

| 1989-05-01 | 6.9% | 5.0% |

| 1989-06-01 | 6.5% | 5.4% |

| 1989-07-01 | 6.1% | 5.6% |

| 1989-08-01 | 5.7% | 6.1% |

| 1989-09-01 | 5.3% | 6.1% |

| 1989-10-01 | 5.0% | 5.6% |

| 1989-11-01 | 4.7% | 5.3% |

| 1989-12-01 | 4.4% | 5.3% |

| 1990-01-01 | 4.0% | 5.8% |

| 1990-02-01 | 3.5% | 5.8% |

| 1990-03-01 | 3.2% | 5.2% |

| 1990-04-01 | 2.9% | 5.1% |

| 1990-05-01 | 2.7% | 5.1% |

| 1990-06-01 | 2.4% | 4.5% |

| 1990-07-01 | 2.0% | 4.1% |

| 1990-08-01 | 1.6% | 3.5% |

| 1990-09-01 | 1.1% | 3.6% |

| 1990-10-01 | 0.5% | 3.7% |

| 1990-11-01 | -0.2% | 3.9% |

| 1990-12-01 | -0.7% | 4.0% |

| 1991-01-01 | -1.3% | 3.6% |

| 1991-02-01 | -1.7% | 3.5% |

| 1991-03-01 | -2.1% | 3.6% |

| 1991-04-01 | -2.2% | 3.4% |

| 1991-05-01 | -2.0% | 3.4% |

| 1991-06-01 | -1.6% | 3.6% |

| 1991-07-01 | -1.3% | 3.4% |

| 1991-08-01 | -1.1% | 3.4% |

| 1991-09-01 | -0.8% | 3.1% |

| 1991-10-01 | -0.8% | 3.2% |

| 1991-11-01 | -0.5% | 3.2% |

| 1991-12-01 | -0.2% | 2.9% |

| 1992-01-01 | 0.2% | 2.9% |

| 1992-02-01 | 0.5% | 3.0% |

| 1992-03-01 | 0.9% | 2.9% |

| 1992-04-01 | 1.0% | 3.2% |

| 1992-05-01 | 0.8% | 3.1% |

| 1992-06-01 | 0.5% | 3.1% |

| 1992-07-01 | 0.2% | 3.0% |

| 1992-08-01 | 0.2% | 3.0% |

| 1992-09-01 | 0.1% | 3.1% |

| 1992-10-01 | 0.4% | 2.9% |

| 1992-11-01 | 0.7% | 2.9% |

| 1992-12-01 | 0.8% | 3.0% |

| 1993-01-01 | 0.9% | 2.9% |

| 1993-02-01 | 0.9% | 3.0% |

| 1993-03-01 | 0.8% | 3.3% |

| 1993-04-01 | 0.8% | 2.9% |

| 1993-05-01 | 0.8% | 3.0% |

| 1993-06-01 | 1.2% | 2.8% |

| 1993-07-01 | 1.5% | 2.9% |

| 1993-08-01 | 1.8% | 3.2% |

| 1993-09-01 | 2.0% | 3.3% |

| 1993-10-01 | 2.0% | 3.3% |

| 1993-11-01 | 2.1% | 3.4% |

| 1993-12-01 | 2.1% | 3.0% |

| 1994-01-01 | 2.4% | 3.1% |

| 1994-02-01 | 2.5% | 3.0% |

| 1994-03-01 | 2.6% | 2.9% |

| 1994-04-01 | 2.7% | 3.1% |

| 1994-05-01 | 2.8% | 3.3% |

| 1994-06-01 | 2.8% | 3.4% |

| 1994-07-01 | 2.8% | 3.5% |

| 1994-08-01 | 2.8% | 3.2% |

| 1994-09-01 | 2.7% | 3.3% |

| 1994-10-01 | 2.7% | 3.3% |

| 1994-11-01 | 2.6% | 3.3% |

| 1994-12-01 | 2.5% | 3.5% |

| 1995-01-01 | 2.3% | 3.4% |

| 1995-02-01 | 2.3% | 3.4% |

| 1995-03-01 | 2.2% | 3.4% |

| 1995-04-01 | 2.1% | 3.3% |

| 1995-05-01 | 1.9% | 3.2% |

| 1995-06-01 | 1.7% | 3.1% |

| 1995-07-01 | 1.7% | 3.3% |

| 1995-08-01 | 1.7% | 3.3% |

| 1995-09-01 | 1.7% | 3.1% |

| 1995-10-01 | 1.8% | 3.0% |

| 1995-11-01 | 1.8% | 3.0% |

| 1995-12-01 | 1.8% | 2.9% |

| 1996-01-01 | 1.7% | 3.0% |

| 1996-02-01 | 1.8% | 3.1% |

| 1996-03-01 | 2.0% | 2.9% |

| 1996-04-01 | 2.2% | 3.1% |

| 1996-05-01 | 2.4% | 3.1% |

| 1996-06-01 | 2.4% | 3.1% |

| 1996-07-01 | 2.5% | 3.0% |

| 1996-08-01 | 2.4% | 3.0% |

| 1996-09-01 | 2.4% | 3.1% |

| 1996-10-01 | 2.3% | 3.1% |

| 1996-11-01 | 2.4% | 3.1% |

| 1996-12-01 | 2.4% | 3.4% |

| 1997-01-01 | 2.6% | 3.2% |

| 1997-02-01 | 2.7% | 3.2% |

| 1997-03-01 | 2.7% | 3.3% |

| 1997-04-01 | 2.7% | 3.3% |

| 1997-05-01 | 2.7% | 3.3% |

| 1997-06-01 | 2.8% | 3.3% |

| 1997-07-01 | 2.9% | 3.2% |

| 1997-08-01 | 3.0% | 3.3% |

| 1997-09-01 | 3.1% | 3.4% |

| 1997-10-01 | 3.3% | 3.4% |

| 1997-11-01 | 3.7% | 3.4% |

| 1997-12-01 | 4.0% | 3.4% |

| 1998-01-01 | 4.3% | 3.2% |

| 1998-02-01 | 4.5% | 3.1% |

| 1998-03-01 | 4.7% | 3.0% |

| 1998-04-01 | 5.0% | 3.0% |

| 1998-05-01 | 5.3% | 2.9% |

| 1998-06-01 | 5.6% | 2.9% |

| 1998-07-01 | 5.8% | 3.0% |

| 1998-08-01 | 6.1% | 2.7% |

| 1998-09-01 | 6.3% | 2.7% |

| 1998-10-01 | 6.5% | 2.5% |

| 1998-11-01 | 6.4% | 2.5% |

| 1998-12-01 | 6.4% | 2.4% |

| 1999-01-01 | 6.4% | 3.0% |

| 1999-02-01 | 6.4% | 3.0% |

| 1999-03-01 | 6.5% | 3.2% |

| 1999-04-01 | 6.6% | 3.0% |

| 1999-05-01 | 6.7% | 3.1% |

| 1999-06-01 | 6.8% | 3.3% |

| 1999-07-01 | 7.0% | 3.3% |

| 1999-08-01 | 7.1% | 3.4% |

| 1999-09-01 | 7.2% | 3.3% |

| 1999-10-01 | 7.4% | 3.6% |

| 1999-11-01 | 7.5% | 3.5% |

| 1999-12-01 | 7.7% | 3.5% |

| 2000-01-01 | 7.9% | 3.3% |

| 2000-02-01 | 8.2% | 3.5% |

| 2000-03-01 | 8.4% | 3.5% |

| 2000-04-01 | 8.6% | 3.6% |

| 2000-05-01 | 8.7% | 3.7% |

| 2000-06-01 | 8.8% | 3.8% |

| 2000-07-01 | 8.8% | 3.8% |

| 2000-08-01 | 8.8% | 4.0% |

| 2000-09-01 | 8.9% | 3.7% |

| 2000-10-01 | 9.0% | 3.7% |

| 2000-11-01 | 9.2% | 3.9% |

| 2000-12-01 | 9.3% | 4.2% |

| 2001-01-01 | 9.2% | 4.2% |

| 2001-02-01 | 9.0% | 4.3% |

| 2001-03-01 | 8.8% | 4.0% |

| 2001-04-01 | 8.5% | 4.1% |

| 2001-05-01 | 8.2% | 3.9% |

| 2001-06-01 | 8.0% | 3.6% |

| 2001-07-01 | 8.0% | 3.6% |

| 2001-08-01 | 8.0% | 3.5% |

| 2001-09-01 | 7.8% | 3.7% |

| 2001-10-01 | 7.4% | 3.6% |

| 2001-11-01 | 7.0% | 3.4% |

| 2001-12-01 | 6.7% | 3.2% |

| 2002-01-01 | 6.6% | 3.1% |

| 2002-02-01 | 6.6% | 2.7% |

| 2002-03-01 | 6.8% | 2.5% |

| 2002-04-01 | 7.2% | 2.2% |

| 2002-05-01 | 7.7% | 2.5% |

| 2002-06-01 | 8.0% | 2.3% |

| 2002-07-01 | 8.3% | 2.4% |

| 2002-08-01 | 8.5% | 2.2% |

| 2002-09-01 | 8.7% | 2.2% |

| 2002-10-01 | 9.0% | 2.4% |

| 2002-11-01 | 9.3% | 2.2% |

| 2002-12-01 | 9.6% | 2.2% |

| 2003-01-01 | 9.6% | 2.1% |

| 2003-02-01 | 9.8% | 2.0% |

| 2003-03-01 | 9.6% | 2.6% |

| 2003-04-01 | 9.5% | 2.9% |

| 2003-05-01 | 9.1% | 2.8% |

| 2003-06-01 | 8.9% | 3.0% |

| 2003-07-01 | 8.9% | 2.9% |

| 2003-08-01 | 9.0% | 2.8% |

| 2003-09-01 | 9.2% | 3.0% |

| 2003-10-01 | 9.4% | 2.8% |

| 2003-11-01 | 9.6% | 2.7% |

| 2003-12-01 | 9.8% | 2.7% |

| 2004-01-01 | 10.2% | 2.7% |

| 2004-02-01 | 10.7% | 3.1% |

| 2004-03-01 | 11.4% | 3.1% |

| 2004-04-01 | 12.0% | 2.7% |

| 2004-05-01 | 12.5% | 2.4% |

| 2004-06-01 | 13.0% | 2.3% |

| 2004-07-01 | 13.1% | 2.4% |

| 2004-08-01 | 13.1% | 2.4% |

| 2004-09-01 | 13.2% | 1.9% |

| 2004-10-01 | 13.3% | 2.3% |

| 2004-11-01 | 13.5% | 2.5% |

| 2004-12-01 | 13.6% | 2.6% |

| 2005-01-01 | 13.8% | 2.6% |

| 2005-02-01 | 14.0% | 2.6% |

| 2005-03-01 | 14.2% | 2.5% |

| 2005-04-01 | 14.2% | 2.9% |

| 2005-05-01 | 14.3% | 3.2% |

| 2005-06-01 | 14.3% | 3.5% |

| 2005-07-01 | 14.3% | 3.6% |

| 2005-08-01 | 14.4% | 3.8% |

| 2005-09-01 | 14.5% | 4.2% |

| 2005-10-01 | 14.4% | 4.1% |

| 2005-11-01 | 14.1% | 4.1% |

| 2005-12-01 | 13.5% | 4.1% |

| 2006-01-01 | 12.9% | 4.3% |

| 2006-02-01 | 12.1% | 4.3% |

| 2006-03-01 | 11.0% | 4.0% |

| 2006-04-01 | 10.0% | 3.9% |

| 2006-05-01 | 8.8% | 3.7% |

| 2006-06-01 | 7.3% | 3.6% |

| 2006-07-01 | 6.0% | 3.5% |

| 2006-08-01 | 4.8% | 3.4% |

| 2006-09-01 | 3.7% | 3.4% |

| 2006-10-01 | 3.0% | 3.2% |

| 2006-11-01 | 2.2% | 3.2% |

| 2006-12-01 | 1.7% | 3.2% |

| 2007-01-01 | 1.0% | 3.1% |

| 2007-02-01 | 0.5% | 2.9% |

| 2007-03-01 | -0.3% | 3.0% |

| 2007-04-01 | -0.8% | 2.7% |

| 2007-05-01 | -1.4% | 2.6% |

| 2007-06-01 | -1.6% | 2.5% |

| 2007-07-01 | -2.0% | 2.5% |

| 2007-08-01 | -2.3% | 2.4% |

| 2007-09-01 | -2.8% | 2.3% |

| 2007-10-01 | -3.5% | 2.2% |

| 2007-11-01 | -4.6% | 2.1% |

| 2007-12-01 | -5.4% | 1.9% |

| 2008-01-01 | -6.4% | 1.8% |

| 2008-02-01 | -7.3% | 1.7% |

| 2008-03-01 | -7.8% | 1.5% |

| 2008-04-01 | -8.1% | 1.6% |

| 2008-05-01 | -8.2% | 1.5% |

| 2008-06-01 | -8.3% | 1.3% |

| 2008-07-01 | -8.4% | 0.9% |

| 2008-08-01 | -8.9% | 0.9% |

| 2008-09-01 | -9.6% | 0.7% |

| 2008-10-01 | -10.3% | 0.7% |

| 2008-11-01 | -10.9% | 0.3% |

| 2008-12-01 | -12.0% | 0.3% |

| 2009-01-01 | -12.7% | -0.4% |

| 2009-02-01 | -12.7% | -0.4% |

| 2009-03-01 | -12.7% | -0.6% |