Verizon shows us why strikes—and unions—matter for working people

40,000 Verizon workers are currently on strike across the country after the company and labor unions failed to reach a new contract agreement last year. Verizon has reaped over $39 billion in profits over the last three years, and its CEO rakes in 200 times more per year than the average Verizon worker. Despite this clear sign of prosperity, Verizon refuses to let its employees share these gains. Instead, Verizon wants to severely cut health care coverage, slash benefits for injured and retired workers, and outsource work to low-wage contractors overseas. As the daughter of a striking Verizon worker and as a union member myself, I know that workers do not decide lightly to go on strike. Strikes are disruptive and stressful, and create financial strain for workers and their families. But they are necessary when large corporations refuse to give working people a fair share of the profits they help create, and Verizon workers have been without a contract for ten months.

By going on strike, the Verizon workers are using one of the few tools workers have left in today’s economy to claim their fair share of economic growth. They are also pushing back against the rigged rules of the economy that privilege capital owners and corporate managers. I stand in solidarity with my mother and thousands of her fellow union members as they fight for a fair contract. Their call for job security, protected benefits, and improved working conditions is emblematic of larger trends affecting working people across America. Their strike is also an example of how important it is for working people to have the right to stand together and negotiate collectively for fair wages and benefits and safe working conditions. Unfortunately, this right has been severely eroded over the fifty years by policy choices made on behalf of those with the most wealth and power—and this erosion has directly contributed to stagnating wages for the vast majority of workers.

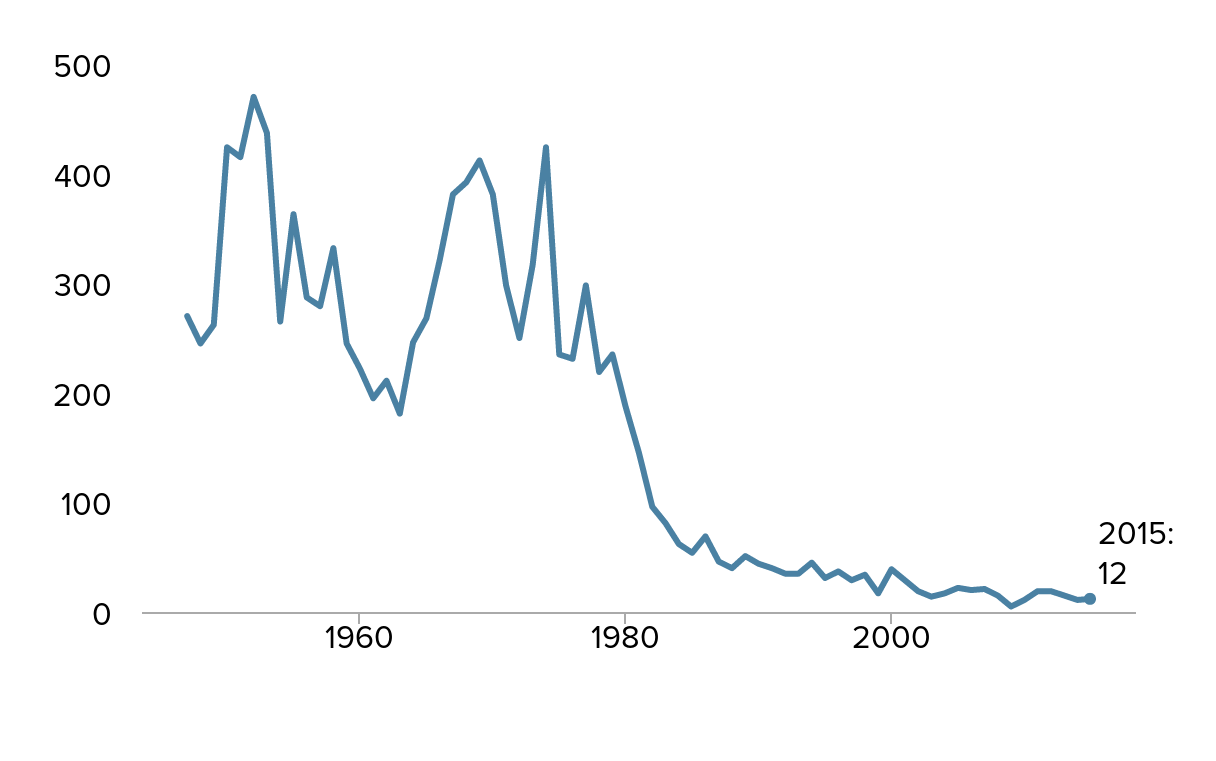

One indication of the declining bargaining power of working people is the sharp decline of work stoppages (which includes both strikes and lockouts) for companies with 1,000 or more employees. The overwhelming reason work stoppages have fallen is because strikes have become far less common. At first, this might sound like good news. In reality, this decline shows how little power workers now feel they have to negotiate higher wages and better working conditions with their employers. In 2015 there were only 12 work stoppages in the U.S. that involved 1,000 or more workers, compared to its last peak of over 400 in 1974.

Work stoppages involving 1,000 or more workers, 1947-2015

| Year | Strikes and lockouts |

|---|---|

| 1947 | 270 |

| 1948 | 245 |

| 1949 | 262 |

| 1950 | 424 |

| 1951 | 415 |

| 1952 | 470 |

| 1953 | 437 |

| 1954 | 265 |

| 1955 | 363 |

| 1956 | 287 |

| 1957 | 279 |

| 1958 | 332 |

| 1959 | 245 |

| 1960 | 222 |

| 1961 | 195 |

| 1962 | 211 |

| 1963 | 181 |

| 1964 | 246 |

| 1965 | 268 |

| 1966 | 321 |

| 1967 | 381 |

| 1968 | 392 |

| 1969 | 412 |

| 1970 | 381 |

| 1971 | 298 |

| 1972 | 250 |

| 1973 | 317 |

| 1974 | 424 |

| 1975 | 235 |

| 1976 | 231 |

| 1977 | 298 |

| 1978 | 219 |

| 1979 | 235 |

| 1980 | 187 |

| 1981 | 145 |

| 1982 | 96 |

| 1983 | 81 |

| 1984 | 62 |

| 1985 | 54 |

| 1986 | 69 |

| 1987 | 46 |

| 1988 | 40 |

| 1989 | 51 |

| 1990 | 44 |

| 1991 | 40 |

| 1992 | 35 |

| 1993 | 35 |

| 1994 | 45 |

| 1995 | 31 |

| 1996 | 37 |

| 1997 | 29 |

| 1998 | 34 |

| 1999 | 17 |

| 2000 | 39 |

| 2001 | 29 |

| 2002 | 19 |

| 2003 | 14 |

| 2004 | 17 |

| 2005 | 22 |

| 2006 | 20 |

| 2007 | 21 |

| 2008 | 15 |

| 2009 | 5 |

| 2010 | 11 |

| 2011 | 19 |

| 2012 | 19 |

| 2013 | 15 |

| 2014 | 11 |

| 2015 | 12 |

Source: EPI analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Work Stoppages data

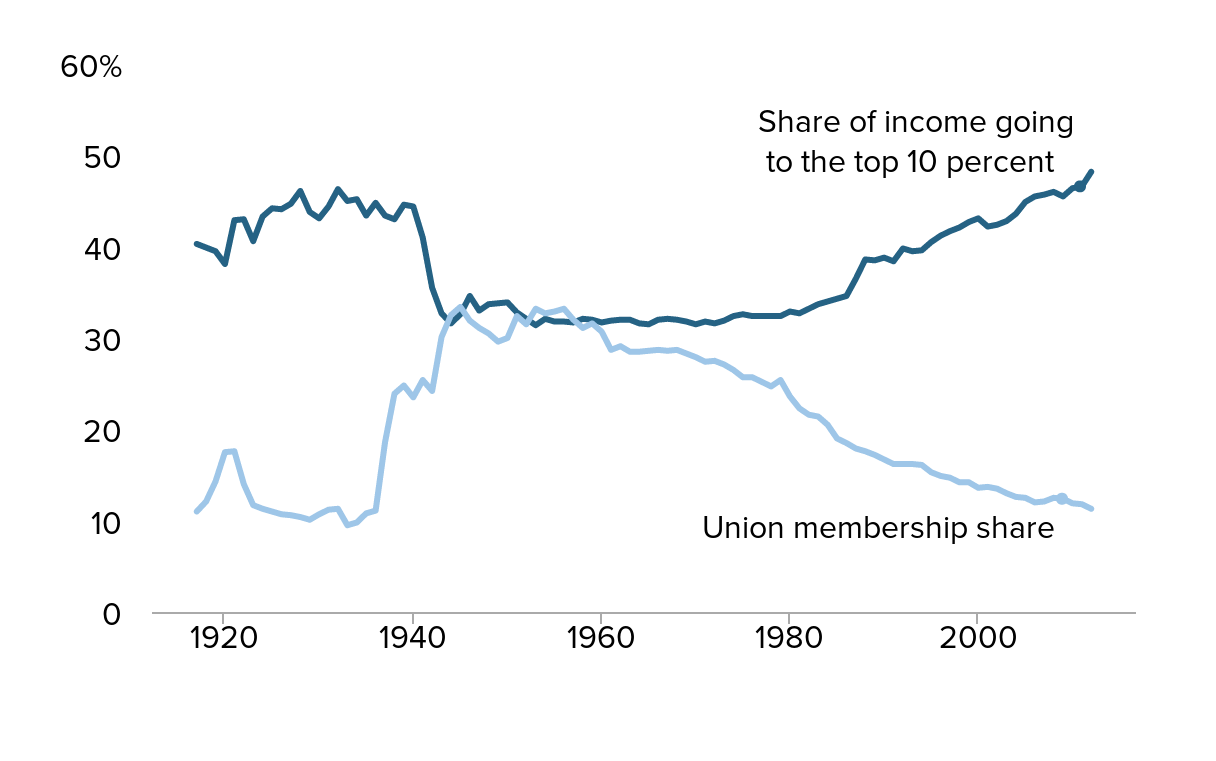

Growing inequality is a direct result of this decline in bargaining power. Policy choices like right-to-work laws and the continuing failure to keep the playing field level between workers that want to form unions and employers that are hostile to unionization have caused union membership to shrink. As membership has shrunk, the middle class has suffered and those at the top have reaped the benefits. Historically, higher union membership has meant that income is shared more equitably throughout the economy. For example, when union membership hit its peak (33 percent) in 1945, only 33 percent of income went to the top 10 percent of wage earners. As union membership began to steadily decline in the 1960s, the share of income going to the top 10 percent began to grow. By 2013, union membership was at only 11 percent and the top 10 percent received nearly half of all income (47 percent).

Decline in union membership mirrors income gains of top 10%: Union membership and share of income going to the top 10%, 1917–2012

| Year | Union membership | Share of income going to the top 10 percent |

|---|---|---|

| 1917 | 11.0% | 40.3% |

| 1918 | 12.1% | 39.9% |

| 1919 | 14.3% | 39.5% |

| 1920 | 17.5% | 38.1% |

| 1921 | 17.6% | 42.9% |

| 1922 | 14.0% | 43.0% |

| 1923 | 11.7% | 40.6% |

| 1924 | 11.3% | 43.3% |

| 1925 | 11.0% | 44.2% |

| 1926 | 10.7% | 44.1% |

| 1927 | 10.6% | 44.7% |

| 1928 | 10.4% | 46.1% |

| 1929 | 10.1% | 43.8% |

| 1930 | 10.7% | 43.1% |

| 1931 | 11.2% | 44.4% |

| 1932 | 11.3% | 46.3% |

| 1933 | 9.5% | 45.0% |

| 1934 | 9.8% | 45.2% |

| 1935 | 10.8% | 43.4% |

| 1936 | 11.1% | 44.8% |

| 1937 | 18.6% | 43.4% |

| 1938 | 23.9% | 43.0% |

| 1939 | 24.8% | 44.6% |

| 1940 | 23.5% | 44.4% |

| 1941 | 25.4% | 41.0% |

| 1942 | 24.2% | 35.5% |

| 1943 | 30.1% | 32.7% |

| 1944 | 32.5% | 31.6% |

| 1945 | 33.4% | 32.6% |

| 1946 | 31.9% | 34.6% |

| 1947 | 31.1% | 33.0% |

| 1948 | 30.5% | 33.7% |

| 1949 | 29.6% | 33.8% |

| 1950 | 30.0% | 33.9% |

| 1951 | 32.4% | 32.8% |

| 1952 | 31.5% | 32.1% |

| 1953 | 33.2% | 31.4% |

| 1954 | 32.7% | 32.1% |

| 1955 | 32.9% | 31.8% |

| 1956 | 33.2% | 31.8% |

| 1957 | 32.0% | 31.7% |

| 1958 | 31.1% | 32.1% |

| 1959 | 31.6% | 32.0% |

| 1960 | 30.7% | 31.7% |

| 1961 | 28.7% | 31.9% |

| 1962 | 29.1% | 32.0% |

| 1963 | 28.5% | 32.0% |

| 1964 | 28.5% | 31.6% |

| 1965 | 28.6% | 31.5% |

| 1966 | 28.7% | 32.0% |

| 1967 | 28.6% | 32.1% |

| 1968 | 28.7% | 32.0% |

| 1969 | 28.3% | 31.8% |

| 1970 | 27.9% | 31.5% |

| 1971 | 27.4% | 31.8% |

| 1972 | 27.5% | 31.6% |

| 1973 | 27.1% | 31.9% |

| 1974 | 26.5% | 32.4% |

| 1975 | 25.7% | 32.6% |

| 1976 | 25.7% | 32.4% |

| 1977 | 25.2% | 32.4% |

| 1978 | 24.7% | 32.4% |

| 1979 | 25.4% | 32.4% |

| 1980 | 23.6% | 32.9% |

| 1981 | 22.3% | 32.7% |

| 1982 | 21.6% | 33.2% |

| 1983 | 21.4% | 33.7% |

| 1984 | 20.5% | 34.0% |

| 1985 | 19.0% | 34.3% |

| 1986 | 18.5% | 34.6% |

| 1987 | 17.9% | 36.5% |

| 1988 | 17.6% | 38.6% |

| 1989 | 17.2% | 38.5% |

| 1990 | 16.7% | 38.8% |

| 1991 | 16.2% | 38.4% |

| 1992 | 16.2% | 39.8% |

| 1993 | 16.2% | 39.5% |

| 1994 | 16.1% | 39.6% |

| 1995 | 15.3% | 40.5% |

| 1996 | 14.9% | 41.2% |

| 1997 | 14.7% | 41.7% |

| 1998 | 14.2% | 42.1% |

| 1999 | 14.2% | 42.7% |

| 2000 | 13.6% | 43.1% |

| 2001 | 13.7% | 42.2% |

| 2002 | 13.5% | 42.4% |

| 2003 | 13.0% | 42.8% |

| 2004 | 12.6% | 43.6% |

| 2005 | 12.5% | 44.9% |

| 2006 | 12.0% | 45.5% |

| 2007 | 12.1% | 45.7% |

| 2008 | 12.5% | 46.0% |

| 2009 | 12.4% | 45.5% |

| 2010 | 11.9% | 46.4% |

| 2011 | 11.8% | 46.6% |

| 2012 | 11.3% | 48.2% |

Source: Data on union density follow the composite series found in Historical Statistics of the United States, updated to 2012 from unionstats.com. Income inequality (share of income to top 10%) from Piketty and Saez, “Income Inequality in the United States, 1913-1998," Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 2003, 1–39. Updated and downloadable data, for this series and other countries, are available at The World's Top Income Database. Updated September 2013.

Strengthening collective bargaining rights is one way we can make sure working people share in the economic prosperity they help create. When the right of workers to negotiate with their employers is strong, the benefits reach working people regardless of whether or not they are in a union. Strong unions mean higher wages and better compensation for all working people and have played a pivotal role in securing legislated labor protections and rights. These include the 40-hour work week, safety and health protections, overtime pay, family and medical leave, and laws that make sure these rights are enforced on the job.

Enjoyed this post?

Sign up for EPI's newsletter so you never miss our research and insights on ways to make the economy work better for everyone.