[THIS TESTIMONY WAS GIVEN BEFORE THE U.S. SENATE COMMITTEE ON HEALTH, EDUCATION, LABOR, AND PENSIONS ON MARCH 27, 2007.]

The Right to Organize, Freedom and the Middle Class Squeeze

Thank you for the opportunity to discuss how to make it possible, once again, for working Americans to exercise their fundamental rights to join together in unions of their choosing.

The topic of today’s hearing couldn’t be more timely. Americans are facing the very challenges that unions help us to address:

Most Americans are working harder and smarter than ever before, but they fear their efforts are not being recognized and rewarded. The growing gaps in wages and wealth threaten the productivity of our economy and the cohesion of our society. And many Americans are opting out of the democratic process at a time when the nation needs their involvement and their ideas.

In our time, we have seen how labor movements can be a force for freedom throughout the world. Recall the achievement of Solidarity to overcome Communist totalitarianism in Poland. Recall the efforts of COSATU to overthrow Apartheid in South Africa. All freedom-loving Americans should favor a strong, vibrant labor movement both here and abroad. Here in the United States, unions can also make an historic contribution by making work pay for those who labor for low wages, by restoring the link between productivity increases and pay increases, and by providing training, health coverage, and portable pension benefits at a time when most Americans will keep moving from job to job.

We know union members can build a better America because that is just what they have done at every crucial moment in our nation’s history, from the days when the First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia — in Carpenters Hall.

As Harvard economists James Medoff and Richard Freeman wrote nearly twenty-five years ago:

“Unions reduce wage inequality, increase industrial democracy and often raise productivity… in the political sphere, unions are an important voice for some of society’s weakest and most vulnerable groups, as well as for their own members.”

In our nation’s public life, unions have been a powerful voice for all working Americans for 150 years. In the 19th century, they won the 10-hour day and then the 8-hour day so that succeeding generations could spend time with their families. In the years before the Great Depression, the unions helped America abolish child labor, establish workmen’s compensation and protect workers’ health and safety on their jobs. During the Depression, union members helped to preserve democracy and restore prosperity by enacting a federal minimum wage, overtime pay and a 40-hour week, creating social security and unemployment insurance, and thereby proving that our political system could serve the interests of the great majority of people. Labor’s victories were America’s victories.

In the succeeding years, union members helped America keep its promise of “liberty and justice for all.” With the visionary leadership of A. Philip Randolph, the Sleeping Car Porters were the unsung heroes of the civil rights movement from the fight for the Fair Employment Practices Commission to the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the March on Washington. Walter Reuther of the UAW was at Martin Luther King’s side in 1963 at the March on Washington. Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach declared that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 would not have passed but for the support and determination of the unions. And Dr. King gave his life supporting sanitation workers who walked off their jobs in Memphis to assert their human dignity. Union members led the fights for the Mine Safety Act, the Occupational Safety and Health Act, ERISA, and laws to protect migrant farm workers. The health care workers and nurses pushed for and won passage of the lastest improvement to our workplace safety laws in 2000, the Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act.

Through all these efforts, and so many more, America’s unions made the United States a fairer, more productive, and healthier society.

Unions build our democracy as well as our economy. Union members and their families are more likely to vote than the average American, and organizations from the Red Cross to United Way benefit from the disproportionate contributions and participation of union members.

Unions in the Workplace

In our workplaces, unions promote opportunity, security, and fundamental fairness.

Through training programs and requirements that job openings be posted and filled fairly, unions help working Americans enjoy a fair chance to get ahead.

Unions make sure that workers are rewarded for their years of service and have regular hours that allow them to plan ahead and spend time with their families.

Union employers are less likely to violate civil rights laws, less likely to violate minimum wage and overtime laws, and more likely to follow workplace safety standards. Twenty-eight percent of coal miners, for example, work in union mines. Yet from 2004 to 2006, only 14% of fatalities occurred in union mines. The odds of dying in a non-union mine were more than twice as great as in a union mine.

Unions ensure due process. In every state but Montana, employment is at will. Employers can fire employees for no reason or any reason, except those specifically proscribed by law, which usually pertain to race, religion, age, gender or ethnicity. Employees with no union to protect them can be fired on a whim, for complaining, for whistleblowing, for dressing wrong, because the foreman doesn’t like them, or for their appearance. Unions, by contrast, almost always demand and win a right to due process and a requirement that the employer establish just cause before disciplining or terminating an employee. By insisting on just cause and due process, unions give their members the security to complain, to have input into how a business is operated, to challenge unsafe, unfair, unlawful, unproductive or wasteful practices and to recommend better alternatives.

In times of hardship, unions help hardworking people have access to the benefits that they have earned, such as unemployment insurance, worker’s compensation, or Trade Adjustment Assistance. Unions often advocate on behalf of their members with government agencies when benefits are denied or delayed.

Of course, unions’ most important contribution is making work pay and compensation more equitable.

When one compares workers whose experience, education, region, industry, occupation and marital status are comparable, those covered by a union agreement enjoy:

• 14.7% higher wages

• 28.2% greater likelihood of having employer-provided health insurance

• 53.9% greater likelihood of having pension coverage

• 14.3% more paid time off

The union wage premium varies by race, ethnicity and gender, but is large for every group:

• Whites – 13.1%

• Blacks – 20.3%

• Hispanics – 21.9%

• Asians – 16.7%

• Men – 18.4%

• Women – 10.5%

In unionized settings there is much less inequality since people doing similar work are similarly paid, race and gender differentials are less, occupation differentials are less, and the wages of front-line workers are closer to that of managerial workers. Unions also lessen inequality because they are more successful at raising the wages of those in the bottom 60% of th

e wage pool.

It is important to note that even non-union employees benefit from the presence of unions in their industry and area. Because of the so-called “threat effect,” non-union employers give their employees higher wages and more generous benefits in order to prevent their own employees from organizing. The clearest example is the Japanese and German transplant auto factories, which for 25 years have paid UAW wages to their non-union employees, even in the rural deep South where wages are generally low, in order to keep them from unionizing. Now that they perceive the UAW as weakened, the transplants are beginning for the first time to pay lower wages – $10-$15 an hour less in some cases.

More generally, unions have raised the standard for most employers and the expectations of most employees by negotiating paid lunch breaks, health benefit coverage, paid vacations, paid sick days, and paid holidays, none of which (shamefully) is required by federal law.

The effects of unions on competitiveness

So do unions help or hurt companies? How does unionized Costco, for example, compete successfully with non-union Wal-Mart even though Costco’s labor costs are 40% higher? How does Costco generate almost twice as much profit per employee as Wal-Mart’s Sam’s Club?

Decades of research show that unions can have substantial positive effects on firm performance.

At least four factors account for the positive impact on performance:

1. Unions give employees a voice in the workplace, allowing them to complain, shape operations, and push for change, rather than simply quitting or being fired. That leads to reduced cost from lower turnover.

2. Union employees feel freer to speak up about operations, leading to improvements that increase productivity. Employment security fuels collaboration and information sharing, leading to higher productivity.

3. Higher pay pushes employers to find other ways to lower costs – with new technology, increased investment, and better management.

4. Union employees get more training, both because they demand it and because management is willing to invest more to get a return on their higher pay.

Research shows that the likelihood of union firms closing or going bankrupt is no greater than for non-union firms. The bottom line is that union firms are just as productive as non-union firms. In the auto industry, for example, even though the non-union foreign transplant companies generally have newer facilities, 6 of the 10 most productive assembly plants are union.

Unions and the National Economy

One of the most important effects of unions has been on reducing inequality. The “great compression” of the mid-20th century, when a huge gap between the wages and incomes of workers on the bottom and at the top closed, began as deliberate government policy during World War II, but was maintained for 30 years by the power of unions to raise workers’ wages and hold the CEOs in check. The American middle class was created in the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s, when unions were strong and guaranteed that the productivity and profit of American industry was broadly shared.

For the last 30 years, as union density has declined, that compression has reversed and inequality has been on the rise. Since 1973, according to Picketty and Saez, the share of market income going to the top 1% has more than doubled, from less than 10% of all income to almost 22% in 2005. The ratio of the wealth of the wealthiest 1% of Americans to those in the middle (e.g., the median) was 125 to 1 in 1962. By 2004, it was 190 to 1.

Studies show that the decline in union membership has been a substantial factor in this rising inequality – responsible for at least 20%. My own research suggests the effect is larger, since most estimates ignore the union threat effect and its loss, the union effect on benefits, and ( as Paul Krugman points out), unions’ cultural effect in helping impose norms that made greed and inflated CEO compensation unacceptable. When unions were strong, CEO pay was “only” 24 times the pay of average workers. Today, with unions weakened, CEO pay is 262 times the pay of average employees.

For 30 years after World War II, a rising economy truly lifted all boats, and Americans at every wage level saw their income rise together. For most of the last 30 years, and particularly in the last five years, with union representation at its lowest share of the labor force since the 1930s, the nation’s enormous wealth has not been fairly shared. Since 1980, the U.S. economy has grown at an annual rate of 3% per year, but the benefits of this growth have gone, as I noted earlier, overwhelmingly to the best-off 10% and among these, especially to the upper 1%. Average working Americans have been getting a shrinking piece of the pie. Inequality has reached levels not seen since before the Great Depression.

Since the late 1970s, inflation-adjusted wages and income for the vast majority of Americans have risen much more slowly than the nation’s productivity and wealth. To the extent that the typical family’s or household’s earnings have risen, it is mostly because family members, especially married women, have worked longer hours. The typical middle class family today works more than 10 hours more per week than a similar family worked in 1979. Between 1975 and 2000, prime age families with children increased their time in the labor market by 900 hours a year – 5 months more work! It’s no wonder that families feel squeezed both in terms of finances and time.

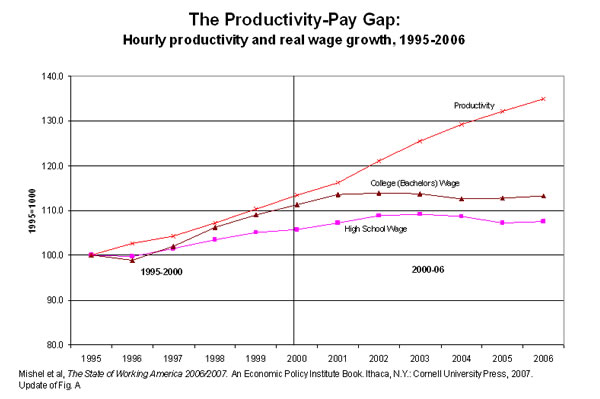

Americans are working not just harder and longer, but more productively. The economy has grown enormously, in large part because the American workforce has been among the most productive in the world. Output per hour of work increased 71% from 1980 to 2005, making possible a dramatic rise in our living standards. But the real compensation, including benefits, of nonsupervisory employees rose only 4%. Productivity over the past 5 years rose almost 20%, but inflation-adjusted wages for workers with a college education have been flat, just as they have for those with a high school diploma. (See Figure )

The Employee Free Choice Act

I have shown that the decline in union representation has been a major cause of two disturbing trends in our economy: the rise in inequality and the failure of average working Americans to share in the benefits of rising productivity. By reducing the opportunity for employers to intimidate and discourage workers from unionizing after they have reached a collective decision to do so, the Employee Free Choice Act can help restore and spread the benefits that unions bring to workers and the economy.

Employees understand the benefits unions bring. Research by Harvard economist Richard Freeman (that I have attached to this testimony) shows that a majority of nonunion non-managerial workers in 2005 would have voted for a union if given the opportunity. If even half of the 58% of employees who want a union had one, the entire economy would be transformed, and I have no doubt that the result would be a much fairer distribution of the economic wealth our nation produces.

The authors of the Wagner Act understood perfectly well that individual employees cannot strike a fair bargain with much more powerful employers. They knew, as Sen. James Webb says, that employees need an agent. Their conclusio

ns are still part of the National Labor Relations Act’s Findings and Declaration of Policy:

“The inequality of bargaining power between employees who do not possess full freedom of association or actual liberty of contract, and employers who are organized in the corporate or other forms of ownership association substantially burdens and affects the flow of commerce, and tends to aggravate recurrent business depressions, by depressing wage rates and the purchasing power of wage earners…”

By requiring employers to accept their employees’ choice of bargaining representative, deterring employer violations of the law, and by requiring arbitration of first contracts when necessary, the Employee Free Choice Act will help restore the purchasing power of average Americans and lift the living standards of the 90% of Americans who have endured the middle class squeeze or been left out of our economic gains altogether.

Lawrence Mishel is president of the Economic Policy Institute in Washington, D.C.

[POSTED TO VIEWPOINTS ON MARCH 27, 2007. ]

Return to SharedProsperity.org