The “wage puzzle” is real—but low inflation and low productivity are also puzzles that need to be solved

Jason Furman’s recent piece in Vox is drawing lots of comments (including one by me on a relatively minor issue). The last couple of months have seen lots of attention focused on relatively weak wage growth even in the face of low unemployment—sometimes referred to as the “wage puzzle.” I and others have argued that this weak wage growth should make us think that by definition there is still slack in the labor market, and this might mean rethinking just how low unemployment can go. Furman argues instead that wage growth is not that low, and that labor markets are tight indeed. A main piece of evidence he highlights to support this view is that both inflation and productivity growth have been low in recent years, and, adjusted for these two influences we really can’t expect wage growth to be any higher than it has been.

Furman is quick to note that his outlook does not demand rapid policy tightening to rein in growth. I’m definitely happy he says this. However, I do think any argument that concludes that the U.S. economy is unambiguously at full employment, and that the labor market is even tighter than the late 1990s, is going to give succor to those calling for the Federal Reserve to continue raising interest rates briskly to rein in growth.

This would be a mistake, and Furman’s arguments should certainly not sway anybody to call for continued policy tightening. He makes some good points, but I think he misreads what low inflation and low productivity are telling us. They are not just background variables that we have to take as given and adjust our wage expectations accordingly. Instead, low inflation and low productivity should be seen as signs of slack in and of themselves.

Take low inflation first. Core inflation has run below the Fed’s preferred target for almost 9 years straight, which is a clear sign of continued demand-slack and a failure to restore the economy to full health. Further, this price inflation target is unlikely to be consistently hit until wage growth firms up. The prices of most things are mostly labor content, so generating price inflation without some wage inflation is pretty hard. Should we just give up on hitting the Fed’s price inflation target and live with slower inflation and slower nominal wage growth? No, we shouldn’t, for a bunch of reasons I laid out here. The main reason is that too-low inflation will see us sail into the next recession with much less room for the Fed to operate at the zero lower bound (ZLB) on interest rates. The ZLB was a key reason why the recovery from the Great Recession was so sluggish, so we should try awfully hard to avoid it, or at least make policy that can still work when we’re there. This means higher, not lower, inflation targets.

Productivity growth has indeed been very slow in recent years. But its collapse coincided with the worst recession in a century. If an extended period of deficient aggregate demand can cause a collapse in productivity, it seems like we should see if an extended period of labor market tightness can cause a recovery (or at least partial recovery). One thing we know (and something that Furman himself has pointed out) is that we should not “nowcast” productivity and assume that the rate that characterized the last one, three, or even five years is a good guide for the future. Further, there are good reasons to think that an extended period of labor market tightness that begins pushing up wage growth will induce more labor cost-saving investments from firms. These firms have gotten lazy about economizing on labor costs in recent years, as labor has been cheap. If labor gets less cheap going forward, we could see this spur a productivity rebound. It’s definitely worth trying.

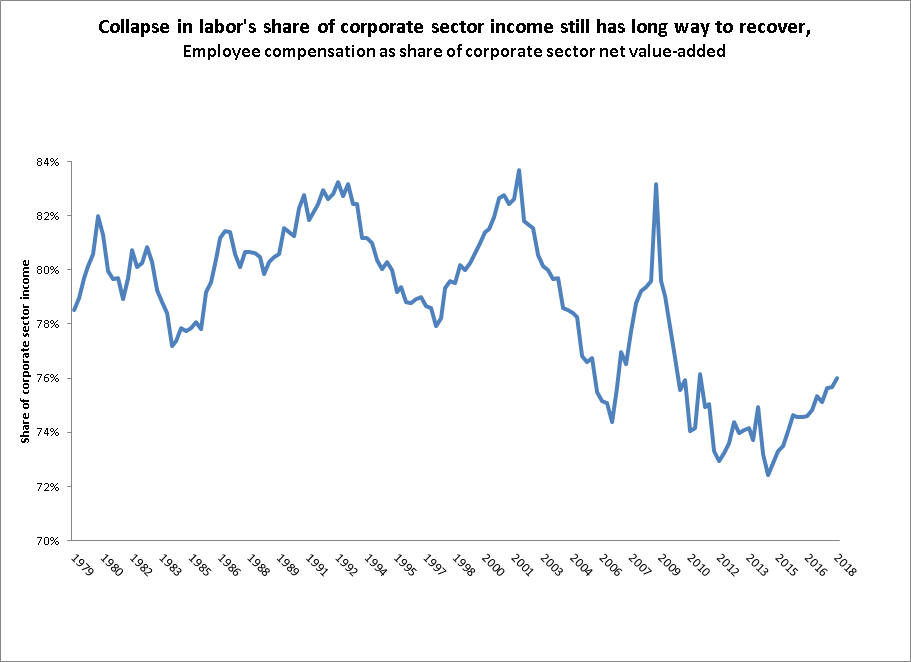

Finally, we should note that over any short run (say less than three years), and especially over any short run characterized by a depressed labor share of income (like we have today), wage growth really isn’t all that constrained by productivity growth. In the long run, if (real) wages grow faster than productivity, then corporate profits as a share of total corporate sector income would shrink to zero, so wages can’t really run that much faster than productivity. But, labor’s share of corporate sector income collapsed early in the recovery following the Great Recession, and that recovery is far from complete. We can certainly afford (and even need!) a period that sees real wages outpace productivity, just to restore the labor share to something close to pre-Great Recession levels (see the figure below for labor’s share of corporate sector income. While we usually track this in real time, last week’s comprehensive GDP revision means that we’re not currently up-to-date on this—but we will be soon).

A few years ago I noted that it would take years of real wage growth exceeding productivity growth to push up labor’s share of corporate sector income even a few percentage points. So, in the long run, productivity growth puts a ceiling on potential wage growth. But I don’t think it makes too much sense to think this ceiling is binding when we’re discussion issues of whether or not the economy has made a full recovery from a deep shock.

Puzzle or not, the evidence still seems clear that all the constellation of risks argue that policymakers—especially the Fed—should stop trying to slow the economy and should instead see just how much we can usefully nudge up wages and inflation and productivity by letting the labor market continue to tighten.

Enjoyed this post?

Sign up for EPI's newsletter so you never miss our research and insights on ways to make the economy work better for everyone.