Opinion pieces and speeches by EPI staff and associates.

[ THIS TESTIMONY WAS GIVEN BEFORE A JOINT HEARING OF THE U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS SUBCOMMITTEE ON SELECT REVENUE MEASURES AND THE COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION AND THE WORKFORCE SUBCOMMITTEE ON EMPLOYER-EMPLOYEE RELATIONS ON JULY 15, 2003 IN WASHINGTON, D.C. ]

Testimony on Bush Administration’s proposal to change funding rules for pension plans

Thank you, Chairman McCrery and Chairman Johnson, Congressman Andrews, Congressman McNulty, and members of the committees for inviting me to speak to you today about the administration’s proposal to change funding rules for pension plans. I am an economist at the Economic Policy Institute, where my research focuses on retirement issues. My testimony is in part based on a paper that I wrote with Dean Baker, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, for the Economic Policy Institute.

Pension Funding Needs to Provide Relief Now and Security in the Future

From a public policy perspective, any proposal to change the pension funding rules should satisfy a two-pronged test: (1) it should at least maintain the security of pension benefits; and (2) promote and sustain sponsorship of defined benefit plans. With these two goals in mind, I will first comment on the administration’s proposal, which fails on the second goal, and then discuss an alternative proposal that would accomplish both goals.

The discussion over the benchmark interest rate that is used to calculate pension liabilities for funding purposes is not just a technical issue. It has real consequences for the retirement security of millions of Americans, who are facing growing risks in preparing for retirement. Many workers still do not have retirement plans through their employers. For the past three decades, more than half of all private sector workers were not covered by a retirement plan. And those workers who have a retirement plan—particularly a defined contribution plan—face more and more risks with their savings. These risks were poignantly illustrated by the fraud and deception that took place at Enron. At the same time, millions of employees face added insecurities as defined benefits are being put in jeopardy due to the perfect storm of pension funding: Falling interest rates, tumbling asset prices, and a weak economy. Securing defined benefits is an important aspect of reducing the growing insecurities that workers are facing with their retirement savings.

Defined benefit plans are an important source of retirement income for millions of Americans. Professor Ed Wolff calculated in a 2002 report for the Economic Policy Institute that in 1998 46 percent of households near retirement could expect some income from defined benefit plans. That is, a large number of households still rely on this secure insurance benefit. Many defined benefit plans often not only pay retirement benefits, but also survivorship benefits and disability benefits. In a world of increasing uncertainty for workers who are preparing for retirement, such insurance benefits are invaluable assets. Consequently, the goal of any proposal to change the pension funding rules should be to secure promised benefits, while sustaining the system for the future. After all, these promised benefits are deferred compensation that employees already earned and that they count on in retirement.

Three Problems Facing Pension Funding

To secure funding for pension plans, three problems need to be addressed. First, the current benchmark interest rate, the 30-year treasury bond yield, that is used to calculate pension liabilities, needs to be replaced since the Treasury no longer issues 30-year bonds.

Second, the decline of the benchmark interest rate came at a time when pension plans saw their assets tumble amidst a stock market crash and when employers were already struggling due to a weak economy. Thus, pension plans are facing numerous short-term funding pressures. In the interest of maintaining the security of pension benefits, public policy should consider rule changes that will offer plan sponsors short-term funding relief.

The third problem is that the current combination of declining interest rates, falling asset prices, and low earnings is recurring as it typically does in a recession. Consequently, current funding rules create a counter-cyclical funding problem and compound the problem by requiring more contributions during a recession than during other times. In order to promote and sustain sponsorship of defined benefit plans, rule changes should occur in a way that is consistent with more stable funding. This would make it less likely that employers would have to make cash contributions when the economy is weak and they are less able to afford them, and more likely that employers will contribute when the economy is strong and businesses are flush.

Evaluating the Administration’s Proposal

The rules proposed by the Bush administration on July 9 may maintain the security of pension benefits in the short-term, but they exacerbate the long-term risks for pension funding and add new problems to the mix. Thus, they put retirement income security for America’s working families further in jeopardy because they put the sustained sponsorship of defined benefit plans at risk. The administration’s proposal envisions the replacement of the 30-year treasury rate with the corporate bond rate for a period of two years, after which it will be permanently replaced by the use of a yield curve. Under a yield curve assumption, the length of each liability is matched to the interest rate for a corporate bond rate with a similar maturity. For example, for a liability that the pension plan has to pay in five years, the discount rate could be the corporate bond rate for 5-year bonds, whereas for a benefit that is payable in 20 years, it could be the rate for 20-year bonds. Lastly, it appears that the administration’s proposal will eliminate the current practice of smoothing interest rates over a 4-year period.

The Administration’s proposal addresses the first problem, of course, by replacing the 30-year treasury rate as the benchmark interest rate.

Second, shifting from the 30-year treasury rate to the corporate bond rate would offer plan sponsors short-term funding relief if current smoothing rules were applied. The 4-year weighted average of the corporate bond rate is about 50 to 70 basis points higher than the currently allowable 120 percent of the 4-year weighted average of the 30-year treasury bond rate. For a typical pension plan, this could mean a reduction in liabilities of about 6 to 8 percent. Hence, pension plan sponsors would receive the short-term relief that they are seeking.

However, third, the short-term relief from the administration’s proposal is a trade off against greater risks in the future, which could jeopardize the sponsorship of some defined benefit plans. The proposed new rules create added uncertainties in several ways. For one, the new rules will presumably eliminate the smoothing of interest rates now allowable under the law. Given past experience this could increase volatility of the interest rate assumption by more than 20 percent. Since interest rates tend to fall in a recession, eliminating the smoothing provisions will result in sharper declines of the underlying interest rate and necessitate larger increases in the required contributions.

Further, the administration’s proposed new rules would require companies to use a myriad of interest rates to value their liabilities instead of just one interest rate for all liabilities. Specifically, the administration believes that the term of t

he asset that the interest rate is based on should match the maturity of the liability.

Aside from technical questions about which bond rates to use, the proposal creates large uncertainties for plan sponsors since they may have to make assumptions about future movements of not one interest rate, but a wide range of them. The relationship between short-term and long-term interest rates changes quickly over time, and it does so more for corporate bond rates than for treasury rates. The ratio of the corporate bond rate to the commercial paper rate is about 50 percent more volatile than the ratio of the 10-year treasury bond yield to the 6-month treasury bill yield.

Further, economic theory says that short-term rates should be lower than long-term rates. However, during a number of periods there was an inverse yield curve, that is, short-term rates were higher than long-term rates. This makes the yield curve even harder to predict.

Adding more uncertainty to pension plan funding could lead employers, who are already concerned about the complexity of pension regulations, to reduce or abandon their pension promises. Workers would suffer as their future benefits are cut back or eliminated all together.

Another uncertainty arises about the transition from the long-term corporate bond rate to the yield curve after two years. Short-term interest rates are typically, but not always, lower than long-term rates. Pension plans’ costs will likely rise – as their assumed discount rates fall – during the transition from a single interest rate to a yield curve. In other words, the respite many employers will enjoy from the replacement of the 30-year treasury rate with the corporate bond rate may be short-lived. As recent events have shown, though, rising costs will provide an incentive for employers to reduce benefits or even terminate plans, undercutting the retirement security for many workers.

Replacing the corporate bond rate with the so-called yield curve creates another problem that could spell greater danger for many workers, especially for those who work in mature industries, such as automobiles. Because the yield curve typically shows lower interest rates for shorter term maturities and higher interest rates for longer term maturities, its use in discounting pension liabilities would make liabilities that have to be paid sooner, such as benefits to older workers, more expensive. Hence, plans with a disproportionate share of older workers would face more rapidly rising costs than other firms when the yield curve is introduced. Consequently, workers in many mature industries, especially in manufacturing, who have already suffered from a prolonged recession in this sector, may be disproportionately likely to lose some of their promised benefits.

To sum up, the administration’s proposal offers some short-term relief, but at the cost of additional future headaches for employers and increased retirement income insecurity for workers.

An Alternative, Smoother Approach to Pension Funding

Does this mean that nothing can be done? Not at all. There is a better way of changing funding rules. As stated earlier, any proposal to change the pension funding rules should at least maintain the security of benefits and promote and sustain sponsorship of defined benefit plans.

A major problem for both employees and employers has been that the current funding rules create a counter-cyclical funding burden, requiring increased contributions, hence a greater likelihood of problems, for plan sponsors during a recession.

An alternative would be to change the rules – to make contributions less volatile and less likely to rise during a recession. In the paper I co-authored with Dean Baker, we discuss three rule changes that would help smooth contributions over time. One of these rule changes addresses the issue of the benchmark interest rate specifically. Our results show that using a smoother interest rate assumption than is currently the practice would reduce the volatility of contributions. It would reduce the required contributions during recessions and increase them during good times, and it would help to improve the overall funding status of pension plans. Put differently, our proposal not only meets the two-pronged test laid out earlier, but it surpasses it. The security of benefits would be improved and adverse incentives for plan sponsors would be reduced.

Current law already allows for some interest rate smoothing in calculating pension liabilities. This provision recognizes that pension plans are a going concern that can expect to receive future contributions, while they are making regular benefit payments. It also recognizes that interest rates can fluctuate quite widely over the course of one or two years. Thus, to stabilize funding for pension plans in a way that will assure the future payment of benefits without unduly burdening employers at any given point in time, the law has permitted some interest rate smoothing.

However, the smoothing of interest rates that is currently allowed still maintains a high degree of volatility. An alternative would be to smooth interest rates over a time horizon that matches the average duration of pension liabilities. The calculations would essentially assume that, during its expected life span, a pension plan will experience interest rates similar to those that prevailed for the past twenty years. To put it differently, since pension plans are going concerns with an average duration of liabilities of well above ten years, they can expect to encounter a number of interest rate scenarios over the next two decades, during which they will invest funds and pay out benefits. The interest rate assumptions should match this flow of funds into and out of pension plans.

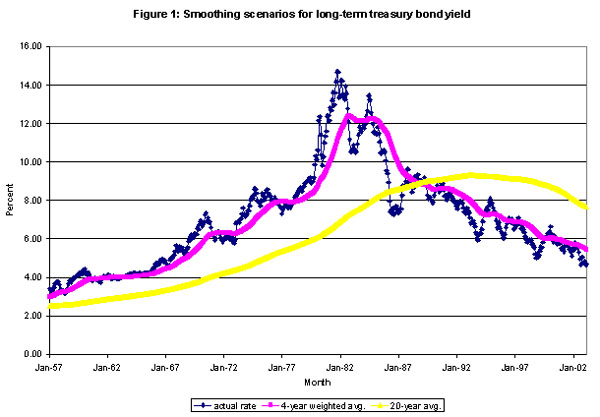

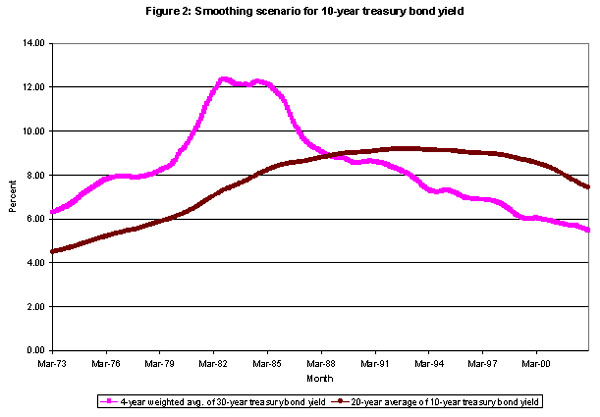

Figure 1 shows what different smoothing assumptions would look like compared to the current practice of the 4-year weighted average. The figure shows that averaging interest rates over 20 years would smooth them considerably compared to the current practice and compared to the current market rate. The same is true if the 20-year average of the 10-year rate is taken (Figure 2). For instance, the difference between the 4-year weighted average of the 30-year treasury bond yield and the 20-year average of either the 10-year or the 30-year treasury bond yield is about two percentage points. In other words, moving from the current benchmark interest rate to the 20-year average of the 10-year treasury bond yield, for instance, would increase the assumed interest rate by about 1 percentage point, and thus would offer even more short-term relief than the administration’s proposal to substitute the corporate bond rate for the 30-year treasury bond rate.

The choice of the interest rate that will be used for this smoothing practice is determined by a number of factors. In principle it should be an interest rate for a fairly low risk security to reflect the nature of pension benefits. It should be an interest rate that can be easily defined, so as to minimize confusion and improve transparency. And it should be an interest rate where sufficient history is available to allow for the calculation of a long-term average. Clearly a number of interest rates will meet these criteria, but the 10-year treasury rate has the advantage that its long-term average is relatively lower than that of other interest rates, such as the corporate bond rate, thus reducing the chance for underfunding in the long-run.

More important than the choice of interest rate is maintaining or even extending the smoothing of interest rates. A longer term average offers the advantage of eliminating cyclical fluctuations in the assumed interest rates, and therefore stabilizing funding during recessions. In our estimates, average contributions from 1952 to 2002 would have been substantially lower than under the current rules, while the actuarial funding ratio would have been higher, reflecting a lo

wered probability of fund failure. That is because contributions would have been made during good economic times, allowing funds to build up reserves for the inevitable bad times.

Consequently, assuming a smoother interest rate would address a number of concerns. It would offer employers funding relief from the pension funding difficulties they are currently experiencing. It would also stabilize employer contributions to pension plans, thereby helping to secure retirement income by reducing the risks to this important insurance benefit. In the same vein, it would reduce the probability of plan failure because it would not burden pension plans as much as current rules do during a recession. Hence, plan termination becomes less likely, reducing the expected burden on the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation.

Conclusion

America’s workers have increasingly been facing the risks of saving for retirement by themselves. An important part of the retirement plan landscape, defined benefit pension plans, offer them some assurance as they prepare for retirement. However, pension plan beneficiaries have experienced an inordinate amount of uncertainty as funding rules required large additional contributions in the middle of a weak economy and the largest stock market crash in U.S. history. Rather than offering employers the small lifeboat of ad hoc relief from this perfect storm, which may jeopardize pension plans in the long term, we need to build a better boat that enables employees, employers, and pension fund regulators to ride out the inevitable rough seas ahead. Funding rules should be changed so that pension benefits can be secured both in the short term and for the foreseeable future. To that end, pension rules should allow for less volatility, less uncertainty, and more transparency.

The administration’s proposal, however, moves exactly in the opposite direction. It makes funding rules more complicated and it adds more volatility to pension funding both by eliminating the beneficial interest rate smoothing that is part of the funding rules right now and by replacing a single interest rate with a widely fluctuating range of interest rates. In the interest of securing pension benefits amid a rising tide of retirement income insecurity, we need to create less, not more, volatility.

Thank you very much for your consideration.

Christian Weller is an economist at the Economic Policy Institute in Washington, D.C.

[ POSTED TO VIEWPOINTS ON JULY 15, 2003 ]