[ THIS TESTIMONY WAS PRESENTED TO THE U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS ON JANUARY 30, 2007. ]

Thank you, Mr. Chairman and members of the committee, for inviting me to testify today. I am submitting as written testimony a paper Jeff Faux wrote for EPI’s Agenda for Shared Prosperity that addresses the problems globalization poses for America’s working families and a set of policy solutions for managing globalization in their interest. My oral remarks will respond to the questions you posed in the hearing notice.

More trade is not the answer

First, is more trade better, regardless of its terms? Not for all Americans, and often not even for most. For working Americans, the effects of the enormous growth in foreign trade have been mostly negative, resulting in the loss of good-paying manufacturing jobs, significant downward pressure on wages, and increased inequality. The doubling of trade as a share of our economy over the last 25 years has been accompanied by a massive trade deficit, directly displacing several million jobs. Most of these jobs were in the manufacturing sector, which included millions of union jobs that paid better-than-average wages. In just the five years from 2000 to 2005, more than three million manufacturing jobs disappeared. We estimate that at least one-third of that decline was caused by the rise in the manufactured goods trade deficit.

U.S. multinational corporations are engaged on both sides of our international trade. About 50% of all U.S.-owned manufacturing production is now located in foreign countries, and a significant part of our manufacturing job loss has been the result of U.S. firms exporting back to the U.S. or producing abroad what they once produced here.

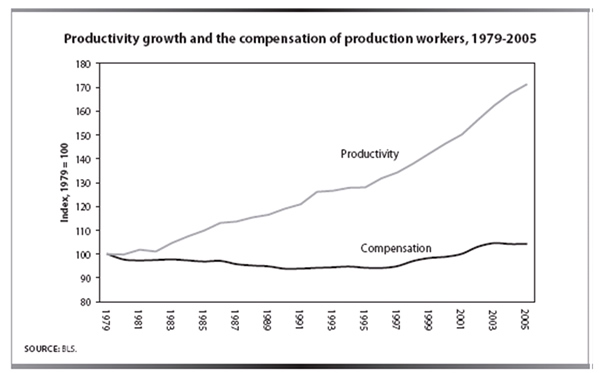

Although the effect of trade on U.S. wages has been less obvious than factory closings or the disappearance of entire industries, trade’s effect on wages has been even more significant and widespread. Despite enormous productivity gains and a steady growth in the gross domestic product, the wages and benefits of non-supervisory workers—80% of the workforce—have been essentially stagnant for the last quarter century. What makes this especially troubling is the fact that, in the past 25 years, the economy has expanded steadily and a better-educated workforce has become far more productive but without sharing in the nation’s economic growth. From 1980 to 2005, productivity in the U.S. economy grew 71%, while the real compensation of non-supervisory workers grew only 4%. The gap in the tradable manufacturing sector is even greater: productivity rose 131%, while compensation of non-supervisors grew only 7%. Real median hourly wages for male workers were lower in 2005 than they were in 1973.

This enormous and still-growing gap between the growth in productivity and that of median (or production worker) compensation baffles many economists, but the contribution of trade and globalization to this stagnation is straightforward and predicted by mainstream economic theory. There are many ways in which globalization has created downward pressure on U.S. wages:

• First, the loss of manufacturing jobs to imports leads to wage losses for the displaced workers, many of whom never regain their former wage levels, even when they find reemployment.

• Second, growing world production capacity lowers the price for traded goods, and because pay is tied to the value of the goods produced, the pay of workers competing to make those goods is reduced.

• Third, the threat of direct foreign competition is used by employers to resist wage increases or to bargain for concessions from their employees.

• Fourth, the flow of investment in plant and equipment and technology overseas raises foreign productivity in sectors that used to be U.S. export strengths, resulting in declining terms of trade and hence declining real income growth.

• Fifth, as trade drives workers out of manufacturing into lower-paying service jobs, the new supply of workers competing for service jobs lowers the wages of similarly skilled service workers.

The cumulative downward pressure on wages and benefits is the most significant economic impact of increased trade on America’s families.

Neither the costs nor the benefits of globalization are being widely shared

In answer to your second question about whether the effects of trade are being fairly shared, the answer again is clearly, no. That trade will make the distribution of income worse is embedded in fundamental economic logic. When American workers are thrown into competition with production originating from low-wage nations, both those workers employed directly in import-competing sectors and all workers economy-wide who have similar skills and credentials will have their wages squeezed. In fact, at the same time as trade flows with low-wage nations have increased, the distribution of income and wealth in the U.S. has grown more and more unequal. Between 1979 and 2004, the richest fifth of American households saw their share of pre-tax income rise by 8 percentage points (from 46% to 54%). The other 80% of American households saw their income shares decline. At the very top of the income scale, the changes are even more dramatic: the richest 1% alone saw their income share rise by 7 percentage points (from 9% to 16%) over this same period, meaning that even the income gain of the richest 20% was actually skewed overwhelmingly toward the very richest of the rich.

While it is hard to quantify the precise contribution of trade to this huge and growing inequality, a large number of studies in the early 1990s made an attempt. The resulting estimates are spread widely but most indicated that trade could account for 10% to 30% of the total rise in inequality between (roughly) 1979 and 1995. The commonly made observation that “most” of the rise in inequality was generated by factors other than trade is often emphasized to allay anxieties about globalization. This is true but not very comforting: 10-30% of a very large number is still a large number. As my colleague Josh Bivens puts it, if I threw myself into a chasm that was only a fifth as deep as the Grand Canyon, I would still be dead.

Framed either in terms of dollars per household or scaled against other economic benchmarks that loom large in the public debate, the results are less comforting. If, for example, trade caused 10-30% of the 25-percentage-point change in the ratio of median-to-average wages over the last 25 years, this translates into wages for the median worker that are 2.2% to 6.6% lower relative to a counter-factual of no increase in trade. Given data on hours worked and wages, this translates into a reduction in annual earnings of $1,000 to $3,000 for the median household by 2005.

The volume of U.S. trade conducted with lower-wage trading partners is the key to assessing how much trade impedes U.S. wage growth. Since 1995, trade with lower-wage countries has more than doubled—scaled against total GDP—implying that the effect of trade on wages may be twice as large as what the earlier literature estimated. In short, trade has likely cost the median household between $2,000 and $6,000 in annual earnings by 2005. Note that $2,000 is roughly the amount of the average annual federal income t

ax paid by households in the middle of income distribution.

To be clear, increased trade does bring benefits, most obviously in terms of reduced prices for traded goods. Two things need to be noted, however. First, the costs described above to American workers are net of any benefits accruing to these workers from lower-priced imports. Second, the scale of these benefits are routinely overestimated, often by a lot. As an example, EPI economist Josh Bivens has examined a literature review published by the Institute for International Economics (IIE) that was cited in a recent paper by the Hamilton Project. This IIE review estimated that the benefits to the U.S. economy of trade liberalization stood between $800 billion to $1.5 trillion in 2004 (roughly 8% of total U.S. GDP). Bivens points out that this estimate is larger by an order of magnitude than what is predicted by standard trade models. The studies reviewed by IIE, and which provide the foundation for the enormous figure they cite, are generally high-quality. It should be noted, however, that these various studiesidentify numerous different channels though which trade could conceivably boost incomes, some contradictory, and not a single one of these argues for a figure anywhere close to the interpretation in IIE’s literature review. In fact, one of the studies most heavily cited by IIE actually finds that trade liberalization has added absolutely nothing in benefits to the U.S. economy since 1982, making the IIE conclusion even more puzzling.

If non-supervisory workers (80% of the labor force) had benefited from globalization, their real wages should have increased over the past three decades. Wage suppression should have been offset by lower prices paid for the goods bought by workers. But real wages of these workers have stagnated, as we have seen. Despite what you hear from many economists, cheap shoes and clothes from WalMart have failed to compensate workers for the costs of globalization (see Atkinson 2002 and Gresser 2006).

There are, of course, industries that benefit from trade, including much of agriculture, various extractive industries, and even some manufacturers. U.S. manufactured exports have increased rapidly since the dollar began to fall in 2002 (8.5% per year through 2005). Exports have grown fastest (in dollar values) in sophisticated and high-tech manufacturing industries such as aerospace and parts, pharmaceutical and medical products, agricultural, construction and other general purpose machinery, and motor vehicles and parts.i However, manufactured imports were 83% larger than exports in 2002, and imports have grown even faster than exports (12.9% per year). As a result, the U.S. trade deficit expanded in every single major manufacturing industry in this period. Exports would have had to grow 83% faster than imports (23.7% per year) just to keep the manufacturing trade deficit from growing.

A new approach to globalization

The specific changes we recommend for dealing with trade begin with what my colleague Jeff Faux has called “a strategic pause”—halting negotiation and approval of trade agreements until Congress and the President agree on a strategy to cut the trade deficit, increase U.S. competitiveness, prevent further erosion of wages, and provide an effective safety net for Americans. This strategic pause is critical because the more we trade under present conditions, the larger the current account and trade deficits grow and thus the more damage we do to working families.

Elements of such a strategy should include:

• Convening a “Plaza II” conference with major trading partners, including China, to manage a gradual depreciation of the dollar, particularly against those nations that actively manage the value of their currency for competitive gain in the U.S. market.

• Targeted investments in energy, education, and new technologies aimed at expanding U.S. production.

• Restoring the bargaining power of American workers who have been undercut by globalization, through increasing (and indexing) the minimum wage and undertaking labor law reform that closes the enormous gap between workers’ desires to join unions and their ability to do so.

• Enactment of universal, affordable health care and pension reform that delivers retirement security to all Americans, not just the wealthiest 20%.

• Freezing programs that encourage importing skilled immigrants rather than training Americans for higher skilled jobs.

• Renegotiating a social contract for NAFTA, allowing for greater aid flows to Mexico and greater policy autonomy and worker and social protections for all three signatories.

• Using U.S. influence in the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and other global agencies to promote interests of workers, both in the U.S. and abroad.

Once the policies are in place to make U.S. exports and domestic industries more competitive and to ensure that the benefits of economic growth are broadly shared, trade deals ought to be pursued under new rules that better protect the interests of workers both here in the U.S. and abroad, and which promote stability in the international financial system. Trade agreements that get “fast track” protection must have:

• Enforceable labor rights and environmental standards, with the same priority status as investor rights;

• No restrictions on U.S. or state governments from favoring domestic producers in economic development policies; and

• Inclusion of protections against currency manipulation.

It should go without saying that compensation programs focused only on job losers, let alone a small subset of them, are an insufficient response to the damage caused by current trade and globalization policies. That damage is widespread throughout the labor force, and a program that makes payments only to certain workers who find a job after being displaced by imports could never be adequate, even if it were a supplement to current programs such as TAA and were carefully structured to avoid encouraging workers to take jobs beneath their level of skill and experience.

The measure of our nation’s trade policies, and for all of our economic policies, must be whether they improve the standard of living of the vast majority of Americans who work for a living. Our current policies have failed that test. It’s past time for a change.

References

Gresser, Edward. 2002. “Toughest on the Poor: Tariffs, Taxes and the Single Mom.” Progressive Policy Institute; PPI Policy Report, Sept. 10.

Griswold, Daniel T. 2006. “Damaging Taxes on Trade”, The Washington Post. Oct. 5.

Endnote

Source: USITC “Trade DataWeb”, http://dataweb.usitc.gov/.

Lawrence Mishel is president of the Economic Policy Institute in Washington, D.C.

[ POSTED TO VIEWPOINTS ON JANUARY 29, 2007. ]