Chairman Durbin, Ranking Member Graham, and distinguished members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify today about the importance of stopping the exploitation of children in violation of our nation’s child labor laws.

My name is Terri Gerstein and I am the Director of the State and Local Enforcement Project1 at the Harvard Center for Labor and a Just Economy.2 I am also a Senior Fellow at the Economic Policy Institute, a nonprofit, nonpartisan research think tank studying the economic wellbeing of low- and middle-income workers and families.3 I work with state and local labor enforcement agencies nationwide, offering training, technical assistance, convenings, and more to help them build their capacity to protect workers’ rights. Previously, I enforced state labor laws for over 17 years in New York, including as Labor Bureau Chief, Deputy Section Chief, and Assistant Attorney General in the New York State Attorney General’s Office and as a Deputy Commissioner in the New York State Department of Labor.

Introduction

With the school year ending, many teenagers are anticipating starting summer jobs. Many of us can remember our own first work experiences, whether during the summer or after school; often they’re a source of growth and learning. Indeed, recognizing the value of these experiences, our laws allow teenagers to work. However, state and federal laws contain important safeguards to ensure that children are not put at risk in highly dangerous jobs, and also to avoid harming their development through excessive work schedules that interfere with schooling.

Most Americans likely thought that oppressive child labor was a problem of the past, something from a century ago that we learn about from history books. But it turns out, that’s not the case. Our country is currently facing a child labor crisis, affecting not only children who are immigrants, but also those who were born here. The federal labor department has reported a 69% increase in child labor violations in the past five years; state labor enforcers have observed notable increases as well. Serious violations have occurred in a range of industries and worksites, from meatpacking plants to fast food restaurants to automobile factories, from construction sites to food processors.

This problem is complex. However, the following measures are urgently needed to stop these abuses:

- Significantly increasing funding to the U.S. Department of Labor (USDOL) for enforcement purposes;

- Increasing civil and criminal penalties for employers’ child labor violations; and

- Creating methods of holding lead corporations responsible for violations within their supply chains.

All children deserve a good start in life: the opportunity to get an education, and initial work experiences that are beneficial and not exploitative. With focused attention on this problem, sufficient resources, and law reform, we can again make oppressive child labor a thing of the past.

Children are legally permitted to work in many jobs

The federal child labor law, located within the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), contains two general sets of prohibitions: one prohibits employers from employing minors in very dangerous jobs, and the other limits the hours children under 16 can be assigned to work, in order to safeguard their ability to get an education.4 State laws vary, but they generally also contain the same two provisions (i.e. barring hazardous occupations and limiting hours of work). Many contain additional protections as well, such as limitations on work hours for older minors (16 and 17) or the requirement that minors obtain a work permit from their school, labor department, or state education agency.

Both federal and state laws allow children, even those as young as 14, to work in a broad range of jobs: work in offices, stocking shelves at grocery stores, working as a cashier, handling most duties at restaurants, working in retail, and much more.

Oppressive child labor is extremely harmful to young people

While age-appropriate work can be valuable for children, oppressive child labor in violation of the law is terribly harmful to them: It places them in serious physical danger and interferes with their opportunity to get an education.

When children work in prohibited hazardous occupations, it places them in serious physical danger, risking injury and even death. The risk of children working in hazardous occupations is not theoretical. When I worked in the New York Attorney General’s Office, our team prosecuted a case involving a 17-year-old high school senior, Brett Bouchard, who was working at an Italian restaurant in upstate New York, near the Canadian border. His arm was severed at the elbow when his employer assigned him to clean machinery that was prohibited for minors. Brett underwent multiple surgeries to have the arm surgically reattached.5

Like Brett, children today are being placed at great risk. Many also have the added vulnerability of being immigrants, not knowing English, sometimes being unaccompanied and on their own. The jobs included in federal (and most state) laws as “hazardous occupations”6 are terribly dangerous. They are among the most dangerous out there for adults, and are even more perilous for children. Prohibited hazardous work includes, for example, mining; demolition; roofing; work involving exposure to radioactive substances; and work involving use, cleaning, or maintenance of various kinds of power-driven machines, such as those used in meat-processing plants.7

Importantly, the jobs included in hazardous occupations were not chosen at random, nor were they selected 85 years ago when the FLSA was first passed. The regulations were most recently updated in 2010, based on data from the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, focusing on the jobs with the highest incidence of serious workplace injury and fatalities.8 There was virtually no opposition to that regulatory update, and very limited comments were submitted.

Young workers are also at higher risk of workplace injuries in general. Young workers have much higher rates9 of non-fatal injuries on the job and the highest rates10 of injuries that require emergency department attention. Due to the vulnerability and inexperience of young workers, data on these workers is likely an undercount due to fears or barriers in being able to speak up and report dangerous situations or child labor law violations.

In addition, when employers require children to work excessive hours, in violation of legal limitations on children’s working hours, it harms young people’s social and educational development, impeding their ability to get an education. Exceedingly long work schedules beyond the legal limits are damaging to children’s education.11 Studies have found that working more than 20 hours per week leads to higher dropout rates12 and lower grades13and interferes with sleep.

There has been an unacceptable upsurge in child labor violations, involving hazardous work and excessive work schedules.

Government statistics indicate a significant and growing problem.

The Wage and Hour Division (WHD) of the USDOL is responsible for enforcing the FLSA’s child labor provisions. The WHD has reported a 69% increase in overall child labor violations in the past five years.14 The Economic Policy Institute analyzed WHD data15 and has reported:16

According to DOL, the number of minors employed in violation of child labor laws in fiscal year 2022 increased 37% over FY2021 and 283% over FY2015. The number of minors employed in violation of hazardous occupation orders increased 26% over FY2021 and 94% over FY2015. These numbers represent just a tiny fraction of violations, most of which go unreported and uninvestigated.

Child labor violations are on the rise: Minors employed in violation of child labor laws and hazardous occupation orders, fiscal years 2015–2022

| Year | Minors employed in violation of child labor laws | Minors employed in violation of hazardous occupation orders |

|---|---|---|

| FY 2015 | 1,012 | 355 |

| FY 2016 | 1,756 | 486 |

| FY 2017 | 1,609 | 491 |

| FY 2018 | 2,299 | 596 |

| FY 2019 | 3,073 | 544 |

| FY 2020 | 3,395 | 633 |

| FY 2021 | 2,819 | 545 |

| FY 2022 | 3,876 | 688 |

Notes: Minors are workers less than 18 years old. Hazardous occupation orders ban minors from working in nonagricultural and agricultural occupations the Department of Labor defines as particularly hazardous for minors, or detrimental to their health or well-being.

Source: EPI analysis of Department of Labor (DOL) child labor violations data.

Authorities have also noted an increase in child labor violations at the state level, in New York17 for example, and Massachusetts, where the attorney general noted that within the past three years, the Office’s Fair Labor Division had cited 127 employers for violating commonwealth child labor laws.18

Media reporting has uncovered serious violations

Media reporting has also uncovered extensive child labor violations involving immigrant children. The stories are heartbreaking and deeply concerning; they illustrate the unique vulnerability of migrant children, as well as the unscrupulous conduct of employers that hire them. Notable examples are as follows:

Reuters in a series of stories19 found migrant children, some as young as 12, were manufacturing car parts at suppliers to Korean auto giant Hyundai in Alabama and working in chicken processing plants in the state. Notably, in the case of the car part suppliers, the children were hired by a staffing company to work for a subcontractor for Hyundai. This kind of outsourcing, multi-layered “fissured” supply chain structure helps household-name lead corporations deflect responsibility for child labor violations, allowing them to blame a subcontractor or staffing agency and evade accountability for what happens during the manufacturing of their products. Reuters coverage describes a fourteen-year-old girl working at the automobile plant “just over four feet tall, with rosy cheeks and a timid smile,” as well as two brothers, aged 13 and 15, who were “staying with other factory workers in a sparsely furnished house owned by the president of the staffing company that hired them.” Articles also report that two adult workers said they raised concerns with management; one was ignored, the other told to focus on production; other adult workers said they noticed the minors but fearing for their own jobs, they didn’t speak up.

The New York Times published an extensive exposé20 regarding widespread child labor violations at a range of employers in various industries nationwide, including at processing plants for household-name foods like Cheerios and Nature Valley, J. Crew and Fruit of the Loom. As in the cases reported by Reuters, these examples include violations at subcontractors working for lead corporations; for example, Hearthside, a food processor where a 15-year-old was working, makes and packages food for other companies, including Frito-Lay, General Mills and Quaker Oats. Notably, the coverage includes an interview showing that employers do have the ability to discern when children are applying for jobs, and to avoid hiring them, belying many employers’ position that it’s the children’s fault for seeking work. Specifically, the article describes a meat plant’s human resources manager who actively tries not to hire children even if they “use heavy makeup or medical masks to try to hide their youth.”

The Boston Globe reported21 on minors working at factories and fish processing plants. The article describes, for example, one youth who “had come from Guatemala on his own to join his father, desperate to escape a poor, violent country where two of his childhood friends were shot to death. From 7 p.m. to 7 a.m., Walter trimmed plastic with sharp knives and retrieved hot molds stuck inside machines, then went straight to Framingham High School, bleary eyed, often falling asleep in class.”

Federal and state meatpacking cases demonstrate the types of violations and challenges in addressing them

Both the United States Department of Labor and the Minnesota Department of Labor and Industry have filed lawsuits seeking and obtaining injunctions against corporations found to have used illegal child labor in violation of requirements regarding hazardous occupations as well as hours of work. The court pleadings in these cases are demonstrative of some of the more important elements of modern child labor: the difficulty of the cases; the uses of subcontractors; and the danger of the work.

1. Packer Sanitation Services, Inc. Ltd. (PSSI) case by the USDOL

In this case, the USDOL found that PSSI had employed more than 100 children in violation of child labor laws in multiple states across the country. The labor department sued PSSI, and ultimately obtained a consent order and judgment,22 in which the company agreed to comply with the FLSA’s child labor provisions in all of its operations nationwide, and to take steps to ensure future compliance, including hiring an outside compliance specialist. The company also paid $1.5 million in civil money penalties for the violations.

Subcontracted model: PSSI is a food sanitation contractor that performs cleaning for the nation’s largest meatpacking companies, including JBS (the largest meatpacking company in the world), Cargill, Tyson Food, and Turkey Valley Farms. Again, we see an example of lead corporations using a subcontractor as a way of seeking to avoid accountability; indeed, on PSSI’s website, it woos potential clients by noting that outsourcing can “take the liability and risk off your facility’s record.”23

Extensive investigation: The court filings in the case (Walsh v. Packers Sanitation Services, Inc., Ltd., U.S. District Court, District of Nebraska, No. 4:22-CV-03246) include declarations from eleven WHD investigators and officials who worked on the case. They describe an extensive and detailed investigation: after receiving a tip that minors were working night shifts, the DOL team performed night-time surveillance on multiple sites and occasions, interviewed many school officials, obtained court warrants for multiple locations, conducted on-site visits at multiple locations from 10 pm to 2 a.m. with teams of around eight Spanish-speaking investigators, took photographs and conducted on-site worker interviews, and obtained, reviewed, and compared extensive company and school records. The document production at 50 agreed-upon PSSI facilities included the digital equivalent of approximately 100,000,000 pages of records. All of this was for one company, to seek a court order mandating that they follow the law.

Investigator declarations provide important details: Although matter of fact in tone, the investigators’ declarations include wrenching details, such as a description of a 14-year-old who had sustained injuries from chemical burns, and who was “falling asleep in class and/or missing class as a result of work.” More examples:

“The minor children interviewed were a mix of boys and girls. In general, the minor children performed cleaning work either by hand, scrubbing machinery and equipment, or with a hose. Chemicals were sprayed on the areas to be cleaned. Minors wore hard hats, ear plugs, goggles, steel toed boots, rubber pants and jackets, gloves, and a harness.”

Minor Child L worked as a sanitor for PSSI in the “loin room”; the equipment listed in that room includes: “three buster saws to cut product, twenty-five trim conveyors to transfer trim products, kidney fat puller to pull meat off sides, scissor chain to move cattle, various saws to cut product, and conveyors to transfer parts of the carcasses.”

“Minor Child P’s work at PSSI involved cleaning the conveyer belt, machines that process the meat, pick up meat from the floor, and uses a pressure hose. They also worked on the kill floor. Minor Child P attends the Worthington High School and is currently in ninth grade.”

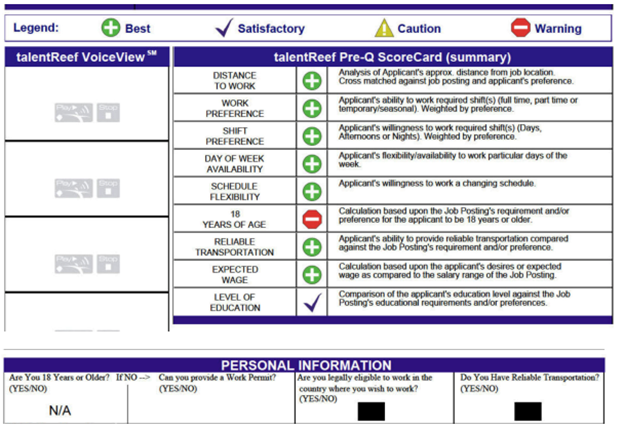

In addition, investigators discovered that PSSI was lax indeed about ensuring compliance with child labor laws. One USDOL-filed court document contains a screen shot from a hiring page in the documents produced by PSSI; six minor children failed to answer a question about their age and were flagged with a red “warning” sign. They were hired anyhow.24

2. Tony Downs Foods. Co. case in Minnesota

In this case, the Minnesota Department of Labor and Industry (Minn. DLI) received a tip that minors were working the overnight shift at a processing plant that makes packaged meat products. As was the case in the Reuters reporting, Minn. DLI was informed that someone had raised a concern about the underage workers with the company but was “told not to ask questions.” Minn. DLI ultimately found children working in hazardous occupations and in violation of the state’s limitations on minors’ hours; the agency obtained an injunction in the case (State of Minnesota v. Tony Downs Foods Co., 83-CV-23-131, Filed 3/15/23), which remains ongoing.

Extensive investigation: Again, the investigation was resource intensive and required considerable skills and time to effectuate. Agency investigators spoke with school officials asking whether they had concerns about students working overnight, working excessive hours, missing school, falling asleep in class, or at risk of dropping out, and school officials said they did have such concerns. Nine investigators executed an on-site investigation in the middle of the night; the team included a Spanish speaking former police officer (eight years of service) and a Spanish speaking former immigration attorney with experience representing families and children. (The minors generally spoke Spanish as their second language, presumably with an indigenous language as their native tongue). Investigators found eight minors working in the plant, and they learned of other minors who had worked there in the past.

Dangerous workplaces: According to court pleadings, the worksite had industrial sized power machinery, mixers, grinders, conveyer belts, ovens, and forklifts. Photographs of the facility show the highly industrial and hazardous nature of the equipment. There was also a freezing process using ammonia which is highly toxic. A young-appearing worker, who turned out to be fifteen, worked in the area where meats were flash frozen with ammonia. Many of the children regularly worked until 1 or 2 a.m.

Readily-identifiable children: The investigators from Minn. DLI identified minors based on their appearance: one was described as “very small in stature (likely under five feet tall) and had young-looking facial features.” An investigator wrote that he “observed another individual of slim build, small stature, and young-looking facial features standing near conveyor belts; they were so cold that they were shaking.”

Additional child labor cases demonstrate the breadth and extent of violations

Numerous additional cases brought by federal and state authorities demonstrate the extent of violations.

Some well-known fast-food companies and/or their franchisees have committed serious violations of child labor laws, most commonly involving infractions related to seriously excessive work hours, but sometimes also including hazardous prohibited work, such as allowing minors to use specific frying or cooking equipment that is disallowed because of the risk of injury. The USDOL found that three franchisees collectively operating 62 McDonalds locations in Kentucky, Indiana, Maryland, and Ohio employed 305 children to work more than the legally allowed hours; at least one also performed tasks prohibited for young workers.25 The youngest workers were ten years old. The investigations led to assessments of $212,544 in civil money penalties against the franchisees. Chipotle, too, is a notable offender: the burrito chain has paid more than $9 million based on thousands of child labor violations in New Jersey (2022)26 and Massachusetts (2020).27 In recent years, state enforcers have also found child labor violations include locations of Burger King, Dunkin’, Wendy’s, Qdoba, Dave & Busters, Taco Bell, and multiple franchisees of Dunkin (in 2021, 2022, and 2023).28 Meanwhile, the USDOL has found child labor violations at Sonic locations in Kansas29 and Nevada,30 as well as a Zaxby’s franchisee,31 Dunkin’,32 another McDonalds,33 Arbys,34 Crumbl Cookies,35 and more. A North Carolina Chick-Fil-A allowed three workers under 18 to operate, load, or unload a trash compactor prohibited as hazardous. (The company also paid certain employees in meal vouchers rather than wages).36

Numerous recent cases also involve youth assigned to do hazardous work prohibited for minors, such as my office’s prior case mentioned earlier: the New York Attorney General prosecuted an employer for assigning a minor to hazardous work that ultimately led to the teen’s arm being severed.37 The USDOL found 14 and 15-year-olds in Maine assigned to use fryers prohibited by law, as well as to operate a power-driven meat-slicer, also not permitted.38 A Pennsylvania meatpacking plant employed minors, including two under 16, to work in dangerous prohibited slaughterhouse operations. 39 A lathe mill in Ohio employed a 15-year-old worker illegally in a hazardous occupation: operating a sawmill, leading to serious injury to the teen “when he became entangled in the gears of a powered wood processing machine.40

In many cases, the oppressive child labor occurred in the context of multiple, additional types of labor violations. This is not uncommon: In my experience enforcing New York’s labor laws, employers that violate one law often violate a cluster of workplace laws. For example, employers that failed to pay overtime in many cases also created false payroll records to hide their violations, along with under-reporting workers’ wages for unemployment insurance, workers’ compensation, or tax purposes. In this way, child labor violations are often part and parcel of an overall approach of employer impunity and disregard for workplace laws.

For example, in one federal case, a 15-year-old worker fell approximately 20 feet off the roof of a two-story Orlando home.41 The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) found that the employer “failed to install a guardrail, safety net or personal fall arrest system for employees doing roofing work,” improperly used ladders, and failed to train workers to recognize fall hazards. The WHD investigated once the minor’s age was known, and not only found violations of the FLSA’s hazardous occupation and hours provisions, but also discovered that the employer had misclassified some workers as independent contractors, did not pay proper overtime, and didn’t pay people for all hours worked. Another USDOL case, this time in Pennsylvania, involved a 17-year-old who fell 24 feet from the roof of a home. The employer was found to have violated not only child labor laws, but also to have misclassified workers as independent contractors, failed to pay overtime, and failed to keep accurate payroll records, as well as exposing other workers to dangerous fall hazards.42

The statistics, media reporting, and enforcement cases all demonstrate: child labor violations are widespread throughout the country, in a range of industries, and there is an urgent need to address them.

Immigrant children are especially vulnerable.

Many adults who have been U.S. citizens their entire lives, even those with graduate degrees and high levels of formal skills, often fear speaking up at work or reporting legal violations by their employers because they fear retaliation and don’t want to lose their jobs. This is a reasonable fear; even though our workplace laws prohibit such retaliation, it frequently occurs.

Imagine, then, the barriers facing teenagers—regardless of their background—in asserting their rights at work.

In addition, immigrant workers, both those who are documented and undocumented, may be less likely to report violations for a host of reasons: language barriers, inaccessible enforcement agencies, unfamiliarity with the law, and concerns about retaliation as well as potential immigration consequences for themselves or their co-workers. Immigrant workers experience higher rates of wage theft, as well as workplace fatalities and injuries.43

Consider, then, the special vulnerability of immigrant children, including—but not limited to—unaccompanied minors.

These children have typically come to the United States fleeing trauma and violence in their home countries. Boston Globe reporting, for example, describes a 16-year-old who worked the overnight shift at a plastics factory and then a greenhouse: “He had come from Guatemala on his own to join his father, desperate to escape a poor, violent country where two of his childhood friends were shot to death.”44

Sometimes children come to the country alone, without their parents, and plan to send money home to their families to help them subsist. Children typically arrive without knowing English, and for many who are indigenous, Spanish is their second language. They do not know the laws of this country, or their legal rights on the job. They want to work, and perhaps they have experience working on a farm back home, but they do not have any idea what it will be like at a meatpacking plant. As a 15-year-old working for a food processor told the New York Times, “I didn’t have expectations about what life would be like here…but it’s not what I imagined.”45 Lacking work authorization, knowledge, networks, children end up in punishing workplaces violating child labor laws, unable to get a job that is appropriate for their age.

In fact, many of these children will ultimately qualify for employment authorization; some, for example, because they are seeking asylum, and others because they may apply for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status. But many do not have access to immigration lawyers. For those who do, the process for obtaining employment authorization is often lengthy.

The special vulnerability of immigrant children workers makes even more urgent the need to take action to stop child labor violations.

Our current system is inadequate to address the child labor crisis.

Noncompliance with workplace laws has been described as a “rational” profit-maximizing decision made by unethical employers in response to low enforcement rates and deficient penalties. Scholars who have analyzed employer costs and benefits of noncompliance find that such “employers will not comply with the law if the expected penalties are small either because it is easy to escape detection or because assessed penalties are small.”46 A broader way of understanding this calculus is that labor law compliance is a product of the likelihood of detection and the seriousness/severity of consequences if detected.

Currently, our system fails on both fronts: the likelihood of detection is exceedingly small, and the consequences of detection are insufficient. Enforcement resources for the USDOL, and for the Wage and Hour Division and Solicitor of Labor’s office, in particular, are grossly insufficient. Two other factors exacerbate this situation: first, the likelihood of detection is further decreased by the unlikelihood of complaints by child workers, given their heightened vulnerability. Second, the likelihood of detection is reduced because of the decline of union density: unions increase worker reporting of violations, presumably because of reduced fear of retaliation; also, union stewards are on-site job monitors who can raise issues about violations without fearing reprisals.

The consequences for violating child labor laws are also insufficient to deter violations. Civil and criminal penalties are very low, and there are no damages available for victims. Further, our laws generally make it far too difficult to hold lead corporations accountable. Lead companies’ use of “fissured” business models47 with outsourced subcontractors and staffing agencies means that these large multinational corporations—those with the greatest ability to prevent child labor in their supply chains—often avoid responsibility for child labor violations—including repeat and widespread violations—occurring in plain sight among the workers directly handling and preparing their products.

Labor enforcement agencies have grossly insufficient resources to address the problem of child labor

The WHD has grossly insufficient resources to effectively enforce our child labor laws. As an initial matter, WHD does not enforce only child labor laws: the agency also enforces the FLSA’s minimum wage and overtime provisions, as well as the Family and Medical Leave Act, and also laws covering federal contract workers, work visa programs, migrant and seasonal agricultural workers, and more. There are an estimated 164.3 million workers covered by these protections, and an estimated 11 million workplaces. In November 2022, there were 810 WHD investigators.48 This means that there is one WHD investigator per approximately 13,580 workplaces. The ratio of investigators per worker is even more stark: one WHD investigator per approximately 202,824 workers. This is two fewer than in 1973 (the first year that data is available), and 422 fewer than the peak year of 1978. Meanwhile, the U.S. economy has grown considerably since then; investigators now are responsible for almost three times as many workers as in 1973. One expert has calculated that WHD in 1938 had 64 times the relative number of inspectors to workplaces.49 State labor agencies are similarly generally inadequately funded to fulfill their missions, including enforcing child labor laws.50

Child labor investigations, as described above, are extremely resource intensive, requiring extensive work by teams of investigators for an extended period of time. The pleadings in the USDOL’s PSSI case and the Minn. DLI’s Tony Downs case demonstrate the complex and challenging nature of these cases. Significantly, these two cases are simply for injunctive relief—the goal is simply to get a court order directing the companies to follow already existing law which they should have been following in the first place! Further, the PSSI case did not include charges seeking liability by lead corporations such as JBS or Cargill that used PSSI. (Such joint employment was not applicable in the Minnesota case). Nor did either case seek damages for the exploited child workers, since no such damages are available under the law for child labor violations. And yet these two cases are extremely complex requiring extensive time, resources, and staff work. If our lawmakers are serious about eradicating oppressive child labor, Congress should allocate significantly more funding to WHD, as well as to the Solicitor of Labor which provides the lawyers to bring these cases in court.

Low union density exacerbates this situation. Where they’re present, unions help prevent violations; they empower ordinary workers to speak out about malfeasance, and provide eyes and ears on the ground that stop abusive practices. But U.S. union density is at record lows (around six percent51 for private sector workers) despite the current popularity of unions unions52 and of organizing.53 This is in large part because our federal labor laws are outdated54 and make it harder than it should be for workers to form and join unions; moreover, funding for the National Labor Relations Board has also stagnated in recent years and last year was facing potential furloughs before getting limited additional funds.55

It is too easy for lead corporations to evade accountability for violations occurring on their worksites, in relation to their products, and in their supply chains

In the PSSI case (described above), other enforcement cases, as well as media reports, there were widespread and blatant child labor violations in the supply chains of major national corporations. Yet it is too easy under current law for these corporations to deflect responsibility for these violations, instead pointing a finger at subcontractors and staffing agencies.

It is the lead corporations, more than any entity, that have the ability to prevent child labor violations in their supply chains. They can extensively monitor their subcontractors, and can also terminate contracts immediately where child labor is found. As two legal experts from the National Employment Law Project recently wrote in Fortune, “Big corporations have the power to ensure compliance with labor and employment laws among their labor contractors and prevent the exploitation of children within their supply chains. They can set minimum labor standards in their supply chains, regularly audit their subcontractors and suppliers to ensure compliance, and cease working with subcontractors and suppliers that violate minimum labor standards. A subcontractor will do whatever it takes to stay in the good graces of major brand names.”56

Further, there is no law of nature that requires large corporations to subcontract. (Like many people, I was surprised to learn that my Cheerios may have been made and packaged by a company called Hearthside, and not by General Mills). Companies that currently use a subcontracting business model, if they want to be sure to avoid child labor violations, can take these jobs in-house. Indeed, JBS recently announced the creation of “JBS Sanitation” in partnership with the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union (UFCW): instead of subcontracting work to PSSI to be performed by exploited and vulnerable migrant children, JBS is “creating hundreds of union jobs across the country” with “competitive wages and benefits.”57 (In contrast, Cargill has said it “will take time,” perhaps months, to sever ties with PSSI.)58

Household-name major multinational corporations have the power and ability to make sure oppressive child labor is not used to produce their products – not used by themselves directly or by subcontractors, staffing agencies, or franchisees. However, our laws make it more difficult than it should be to hold them accountable. This is so even if there are repeat child labor violations within supply chains for the same corporation: it is an uphill battle to hold lead corporations responsible and they have ample legal resources to resist such cases in court.

The definition of “employ” under the FLSA is extremely broad—”to suffer or permit to work”—which would seem on its face to readily allow accountability for lead corporations in supply chains. Yet the case law that has developed over the years makes it much more difficult than it should be to get a finding of joint employer status, often focusing on factors very particular to the individual worker, such as who hired the worker, set their pay, directly supervised the work, and similar considerations.

As NELP’s legal experts recently wrote,

We…need laws that ensure large corporations with the power to eradicate child labor in their supply chains use that power. Major brands should be held strictly liable for egregious labor violations in their labor supply chains. They should be held responsible regardless of whether they knew about the violations. Strict liability will make corporations detect and root out exploitative working conditions among their contractors and suppliers, and eliminate the Dickensian conditions suffered by migrant children.59

Lead corporations may claim they didn’t know about child labor violations in their supply chains; clearly, they have the ability to learn of such abuses and in some instances, given the widespread nature of violations, it somewhat defies credulity to think that the companies at the top of the chain didn’t know. At the very least, though, it’s hard to imagine any reason at all not to impose strict liability on lead corporations for second and subsequent violations discovered in their supply chains; at that point, there is no question regarding their knowledge and ability to remedy.

Finally, the government can and should ensure that it does not enter into contracts with corporations that have a history of child labor in their supply chains. One example of this approach: the recently-proposed Child Labor Exploitation Accountability Act would prohibit the Department of Agriculture from entering into contract with companies that have committed egregious labor law violations and/or contracted with vendors that have committed and failed to rectify serious labor violations.60

Penalties are too small to deter violations

Currently, the penalties are too low to deter violations. At the federal level, civil monetary penalties are in the $15,000 range per child. State penalties can be even lower; for example, Colorado’s penalty for a first-time child labor violation is a puny $20 to $100.61 Fortunately, there are currently proposals in Congress to significantly increase child labor penalties. This should be done, but it alone will be insufficient. A lead corporation is not likely to be deterred by even substantial penalties if it can readily deflect accountability to its subcontractors, and those subcontractors will likely be unmoved by high penalties if their violations are highly unlikely ever to be detected.

While there is criminal liability for child labor violations under the FLSA, it is limited to a misdemeanor for willful violations, and prosecutions happen rarely, if ever. Increased criminal sanctions for employers should be considered.

Additional measures could address the child labor crisis

In addition to the above changes (increased enforcement funding, accountability for lead corporations, and increased penalties), some additional measures could also help address the current crisis.

The simplest of these would be extending by sixty days the statute of limitations for FLSA’s “hot goods” provision, which allows the USDOL to obtain a court order halting the shipment of goods produced in violation of child labor laws. For child labor law violations, the department must do this within 30 days, which is far shorter than the 90-day “hot goods” period for minimum wage and overtime violations. Stopping tainted goods from reaching consumers is a powerful way to ensure that corporations take responsibility; increasing the hot goods period for child labor to 90 days, consistent with the minimum wage provisions, would be an easy, uncomplicated legislative fix that would help the labor department fight child labor.

Enabling migrant teenagers who are applying for immigration status to more quickly obtain employment authorization would help. Work authorization helps immigrants obtain bettwe jobs, with above-board, age-appropriate employment with safe companies that do not violate the law.62 Many migrant children wish to work and to send money home to their families; as stated at the outset of my testimony, minors above 14 are allowed to work and there are plenty of safe, lawful employers currently looking for workers. Many children entering the country are applying or will apply for asylum or special immigrant juvenile status (SIJS); as such, they are entitled to employment authorization, but these processes are slow. Enabling such children to have work authorization more quickly would help them avoid exploitative and dangerous jobs.

All government leaders can play a role by using their public profile to heavily publicize child labor violations when they occur. Research in the workplace safety and health context63 has found that OSHA press releases deterred violations by peer employers. Government leaders can also publicly seek answers from lead corporations with child labor violations in their supply chains, as Senators Alex Padilla and John Hickenlooper did in April of this year.64

Some additional law reform measures to consider include:

- Creating a private right of action for child labor violations. Currently the only method for enforcing these laws is through government enforcement. Adding a private right of action would expand the pool of cases being brought and serve as a resource multiplier by allowing nonprofit, pro bono, and private lawyers to sue for violations.

- Creating and funding a right to counsel for unaccompanied minors in their immigration cases would increase the chances that child labor violations would be detected, since children’s lawyers would likely be aware of their work activities.

- Creating a qui tam right of action for whistleblowers who learn of child labor violations. Allowing them to receive a portion of penalties recovered would incentivize reporting of violations to the government.

- Adding liquidated or compensatory damages to the child labor statute would help compensate victims for their experiences, while also creating additional deterrence preventing employer violations.

- Finally, New York State has an innovative “tagging” provision applicable to the garment industry; it allows the state labor department to attach a tag on unlawfully manufactured apparel labeling it as such, which would no doubt hurt sales. Similar measures could be useful at the federal level.65

States should strengthen, not weaken their own child labor laws.

States, and in some cases localities, can also take action to protect children from exploitation. They can implement the measures described above, including increasing labor enforcement funding, enhancing child labor penalties, imposing strict liability, and more. In addition, states can pass laws related to workers’ compensation to further deter child labor violations and compensate victims. For example, some states have higher payment amounts for permanent workplace injuries suffered by children, given that the injury will affect their lives for a longer period of time than it would an adult. A bill proposed in Colorado would allow a child or their parent to bring a tort lawsuit for damages, and not be limited only to workers’ compensation as a remedy, if an injury occurs during a week in which the minor was engaged in work prohibited by state child labor law, or in which the employer intentionally required the minor to work excessive hours.66 Facing a child labor crisis not seen in decades, the solution is to improve our laws and enforcement.

In contrast, weakening child labor laws is the absolute wrong approach right now. Yet paradoxically, there is a movement afoot in a number of states to do precisely that.67 Bills to weaken child labor standards have been introduced in fourteen states in the past two years alone. Two states—Arkansas and Iowa—have enacted notable rollbacks that will place vulnerable children at risk, and are poorly considered in other ways as well.

Arkansas has eliminated a prior requirement for children to obtain an employment certificate issued by state labor officials. Passed in the guise of protecting parents’ rights, the new law will do precisely the opposite: among other things, applications for the now-eliminated employment certificate required submission of proof of age and written consent of the minor’s parent of guardian.

Meanwhile, Iowa has enacted “one of the most dangerous rollbacks of child labor laws in the country,” according to the Economic Policy Institute.68 The bill changes state law to allow employers to hire children as young as 14 for previously prohibited hazardous jobs in industrial laundries or as young as 15 for light assembly work; to allow state agencies to waive restrictions on hazardous work for 16 to 17-year-olds in a list of dangerous occupations, including demolition, roofing, excavation, and power-driven machine operation; to allow restaurants to hire teens as young as 16 to serve alcohol; and to extend permissible work hours for children as young as 14 to work six-hour nightly shifts during the school year.

This rollback is irresponsible and will put children in harm’s way, placing them in dangerous workplaces that are high-risk for adults and even more so for minors. In addition, multiple provisions in the new state law conflict with FLSA’s child labor provisions. Indeed, the U.S. DOL Solicitor of Labor Seema Nanda sent a letter to an Iowa legislator last month explaining how the new law contradicts FLSA requirements.69

In this way, Iowa lawmakers have put state’s employers in a difficult situation. The FLSA is a floor, not a ceiling; employers must follow the FLSA no matter what. (If state law is stronger, they must follow that also.) Iowa employers may rely on the new state law, and later find themselves facing significant penalties because of FLSA child labor violations. Iowa legislators perhaps believed they were serving employers’ interests, but in fact they were placing employers on a path toward potentially violating federal law.

To the extent that a labor shortage exists, fourteen-year-olds are not the solution

Some have pointed to a “labor shortage” as one reason for relaxing child labor laws. But to the extent such a shortage exists, enlisting vulnerable teens to fill our workforce needs is not the solution. There are other methods to address labor needs in certain sectors. (It’s worth noting, as well, that if child labor laws are relaxed because of a purported labor shortage, they’re unlikely to be tightened up again once conditions change.)

As an initial matter, reports of a “labor shortage” are greatly exaggerated. As Josh Bivens of the Economic Policy Institute has recently pointed out, there is no longer any evidence of an economy-wide labor shortage relative to pre-pandemic trends (the number of prime-age adults working is now higher than 2019 levels).70

Other commentators have noted that more than a labor shortage, we have a good jobs shortage.71 In the words of a Center for American Progress report, “there is a simple solution: make workers a better offer.” Indeed, research published in 2022 showed that those surveyed would take meatpacking jobs if they paid just a little better, around $2.85 more per hour.72 Benefits like health insurance, retirement benefits and signing bonuses also would encourage them. Other factors could also help lure prospective employees, such as paid sick leave (which millions of workers still lack) or predictable schedules.

In addition, unionization can help attract workers.73 For example, a solar installation company struggled to find workers amid an electrician shortage, but reported that once the company became unionized, it opened up a new pool of workers from the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers.74 Unions can reduce turnover and increase employee retention; this union advantage has been cited as a reason for recent success of unionized UPS in hiring and recruiting compared with FedEx and Amazon, which struggled to attract workers in recent years.

To the extent there is a labor shortage, however, it can be addressed without putting children in danger. There are other ways to increase the pool of available workers. For example, thousands of asylum seekers in the United States are legally entitled to be granted employment authorization.75 Additional funding to enable swifter processing of these applications would help them enter the workforce more swiftly; these are age-appropriate adult workers with legal status, already present in the country. Advocates76 and a coalition of more than fifty mayors77 have proposed additional measures to speed up processing of employment authorization applications.

Finally, while the question of comprehensive immigration reform is outside of the scope of my expertise, measures that increase the pool of age-appropriate adult workers would help address any labor shortage that might exist, in a far more lawful and safe manner than relaxing state labor laws to enable more exploitation of vulnerable teens.

Conclusion: Our country can and must protect children

The focus of this hearing is on ensuring the safety and well-being of unaccompanied children. It should be clear from my testimony that the problem of oppressive child labor—whether affecting unaccompanied children or teens born in the United States—stems from employers violating the law: companies that exploit children, make them work excessive hours that endanger their education, and hire them to work in hazardous situations that endanger their bodies and lives. Child labor also results from large corporations that use subcontracting models and willfully turn a blind eye to child labor violations in their supply chains, even when violations are repeated or widespread.

Put simply, if employers did not hire children to do dangerous work for long hours in violation of the law, our child labor crisis would not exist.

We can do better, though. When teenagers go to work—migrants or U.S.-born alike—we can and must keep them safe.

Thank you again for the opportunity to testify. I look forward to your questions.

Notes

1. https://clje.law.harvard.edu/state-and-local-enforcement-project/

2. https://clje.law.harvard.edu/

3. https://www.epi.org/

4. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/WHD/legacy/files/childlabor101.pdf

5. https://www.wbur.org/news/2014/05/16/brett-bouchard-severed-arm-pasta-machine; https://www.northcountrypublicradio.org/news/story/26883/20141211/violi-s-restaurant-owners-violated-child-labor-laws

6. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fact-sheets/43-child-labor-non-agriculture

7. There are some very limited exceptions for supervised training programs with sufficient oversight and protection, approved by the federal labor department.

8. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2010/05/20/2010-11434/child-labor-regulations-orders-and-statements-of-interpretation

9. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6935a3.htm

10. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/youth/default.html

11. https://www.nytimes.com/2001/01/29/nyregion/problems-seen-for-teenagers-who-hold-jobs.html

12. https://nclnet.org/working_more_than_20_hours_a_week_is_a_bad_idea_for_teens/

13. https://www.washington.edu/news/2011/02/09/working-more-than-20-hours-a-week-in-high-school-can-harm-grades-uw-researcher-finds/

14. https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/osec/osec20230227

15. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/data/charts/child-labor

16. https://www.epi.org/publication/child-labor-laws-under-attack/

17. https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-hochul-announces-new-measures-combat-rise-child-labor-violations-and-labor

18. https://www.mass.gov/news/ag-campbell-convenes-community-leaders-issues-guidance-to-raise-awareness-of-child-migrant-child-workplace-protections

19. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/section/underage-workers/

20. nytimes.com/2023/02/25/us/unaccompanied-migrant-child-workers-exploitation.html

21. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2023/03/26/business/ive-learned-that-things-have-cost-meet-migrant-children-working-long-hours-factories-fish-plants-across-mass/

22. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OPA/newsreleases/2022/11/22%202285%20NAT%20WHD%20PSSI%20COJ.signed.pdf; https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/whd/whd20221206-3

23. https://www.pssi.com/2022/11/5-reasons-why-food-processors-should-consider-outsourcing-sanitation/

24. Secretary of Labor’s Reply to the Defendant’s Opposition to the Secretary’s Motion for a Preliminary Injunction, Walsh v. Packers Sanitation Services, Inc., Ltd., U.S. District Court, District of Nebraska, No. 4:22-CV-03246

25. https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/whd/whd20230502-0

26. https://www.cbsnews.com/philadelphia/news/chipotle-new-jersey-child-labor-law-settlement/

27. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/28/business/chipotle-child-labor-laws-massachusetts.html

28. https://www.bostonglobe.com/business/2017/12/19/burger-king-franchisee-cited-for-child-labor-violations-massachusetts/pQf8d62l8tme8Qrvh7TbkL/story.html; https://www.boston.com/news/local-news/2022/10/31/westford-group-settles-child-labor-violations-dunkin-donuts-maura-healey/; https://www.bostonglobe.com/2020/02/17/business/child-labor-violations-piling-up-state/?event=event12; https://www.mass.gov/news/dave-busters-to-pay-over-275000-to-resolve-allegations-of-meal-break-and-child-labor-violations-in-various-locations; https://www.columbian.com/news/2018/aug/03/woodland-taco-bell-owner-fined-for-worker-violations/; https://www.mass.gov/news/dunkin-donuts-franchise-owner-to-pay-120000-to-resolve-numerous-child-labor-law-violations; https://www.boston.com/news/local-news/2022/10/31/westford-group-settles-child-labor-violations-dunkin-donuts-maura-healey/; https://www.mass.gov/news/ag-campbell-issues-citations-totaling-over-370000-for-child-labor-violations-against-two-dunkin-franchisees-with-locations-across-massachusetts

29. https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/whd/whd20230601

30. https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/whd/whd20230530

31. https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/whd/whd20230421

32. https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/whd/whd20230316

33. https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/whd/whd20230222-2

34. https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/whd/whd20230103

35. https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/whd/whd20221220

36. https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/whd/whd20221219

37. https://ag.ny.gov/press-release/2014/ag-schneiderman-secures-criminal-conviction-employers-child-labor-case

38. https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/whd/whd20230206-2

39. https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/whd/whd20230214-1

40. https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/whd/whd20230405-0

41. https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/whd/whd20230310

42. https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/whd/whd20230321

43. https://www.nilc.org/2023/01/27/two-years-after-deadly-nitrogen-leak-at-georgia-poultry-plant-a-big-step-forward-to-protect-immigrant-workers-reporting-labor-abuses/

44. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2023/03/26/business/ive-learned-that-things-have-cost-meet-migrant-children-working-long-hours-factories-fish-plants-across-mass/

45. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/25/us/unaccompanied-migrant-child-workers-exploitation.html

46. Ashenfelter, Orley, and Robert S. Smith. 1979. “Compliance with the Minimum Wage Law.” Journal of Political Economy 87, no. 2 (1979): 333–350. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/260759

47. Weil, David. 2014. The Fissured Workplace: Why Work Became So Bad for So Many and What Can Be Done to Improve It. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2014.

48. https://www.epi.org/publication/testimony-prepared-for-the-u-s-senate-committee-on-the-judiciary-for-a-hearing-on-from-farm-to-table-immigrant-workers-get-the-job-done/#epi-toc-14

49. https://www.npr.org/2023/03/05/1161192379/hundreds-of-migrant-children-work-long-hours-in-jobs-that-violate-child-labor-la

50. https://www.politico.com/story/2018/02/18/minimum-wage-not-enforced-investigation-409644

51. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/union2.pdf

52. https://news.gallup.com/poll/398303/approval-labor-unions-highest-point-1965.aspx

53. https://www.wbur.org/cognoscenti/2022/09/05/worker-organizing-labor-day-thomas-kochan-wilma-liebman

54. https://www.epi.org/publication/why-workers-need-the-pro-act-fact-sheet/#:~:text=PRO%20Act%20solution%3A%20The%20PRO,suffer%20other%20serious%20economic%20harm.

55. https://www.nlrb.gov/sites/default/files/2022-11-18-letter-to-appropriators.pdf

56. Laura Padin and Sally Dworak-Fisher, “Corporations have a duty to prevent child labor abuses in their supply chains. Here’s how they’re still getting off the hook,” Fortune, March 16, 2023. Available at https://fortune.com/2023/03/16/corporations-child-labor-abuses-supply-chains-brands-labor/

57. https://jbsfoodsgroup.com/articles/jbs-usa-announces-creation-of-jbs-sanitation

58. https://www.reuters.com/business/sustainable-business/cargill-needs-months-fully-cut-out-us-firm-fined-child-labor-2023-04-25/

59. Padin and Dworak-Fisher, 2023, Available at https://fortune.com/2023/03/16/corporations-child-labor-abuses-supply-chains-brands-labor/

60. https://www.booker.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/child_labor_exploitation_accountability_act.pdf

61. https://law.justia.com/codes/colorado/2017/title-8/labor-i-department-of-labor-and-employment/article-12/section-8-12-116/

62. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/daca-boosts-recipients-well-being-and-economic-contributions-2022-survey-results/

63. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.20180501

64. https://www.hickenlooper.senate.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Full-Letter-to-Child-Labor-Exploitaition-final.pdf

65. https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/laws/LAB/341-A

66. https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/hb23-1196

67. https://www.epi.org/publication/child-labor-laws-under-attack/

68. https://www.epi.org/blog/iowa-governor-signs-one-of-the-most-dangerous-rollbacks-of-child-labor-laws-in-the-country-14-states-have-now-introduced-bills-putting-children-at-risk/

69. https://www.senate.iowa.gov/democrats/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/DOL-Child-Labor-Law-Response.pdf

70. https://www.epi.org/publication/testimony-prepared-for-the-house-committee-on-small-business-for-a-hearing-on-prices-on-the-rise-examining-the-effects-of-inflation-on-small-businesses/

71. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/its-a-good-jobs-shortage-the-real-reason-so-many-workers-are-quitting/

72. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jaa2.8

73. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2021/12/14/is-your-business-struggling-with-the-labor-shortage-consider-a-union/

74. https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2022/10/03/want-career-saving-planet-become-an-electrician/

75. https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/data/I765_P_AllCat_C08_FY2023Q1.pdf

76. https://help.asylumadvocacy.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/12.12.22-Letter-Addressing-Inefficiencies-re-EADs.pdf

77. https://assets.nationbuilder.com/citiesforaction/pages/524/attachments/original/1680009071/C4A_Employment_Authorization_Advocacy_Letter.pdf?1680009071