Issue Brief #316

As the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction negotiates the second phase of deficit reduction under the Budget Control Act, it is imperative that its proposals include greater revenue to equitably balance the sole focus on spending cuts in the first phase. President Obama has produced a set of recommendations for the committee that would balance additional spending cuts and a winding down of war spending with new revenues and fully financed job creation measures. This issue brief analyzes the revenue proposals in the president’s recommendations and offers a menu of alternative or supplemental progressive revenue options to reduce the deficit and/or finance job creation initiatives. As detailed in this brief:

- The president’s revenue recommendations for the joint committee mark a step toward revenue adequacy and a more equitable tax code relative to current tax policies by raising $1.3 trillion in new revenue over the next decade relative to current tax policies.

- The president’s proposed tax changes would predominantly affect the top 5% of earners (with incomes above $227,000) while cutting average taxes for the bottom 60% of earners (with incomes below $65,000).

- The president’s revenue recommendations, however, fall $3.4 trillion shy of projected revenue under current law. Revenue inadequacy and the Bush-era tax cuts remain prime drivers of budget deficits and are only partially addressed by the president’s recommendations.

- Beyond the president’s recommendations there remains substantial scope for increasing the progressivity of the tax code and raising additional revenue to finance job creation, ease budgetary pressures elsewhere, and reduce deficits.

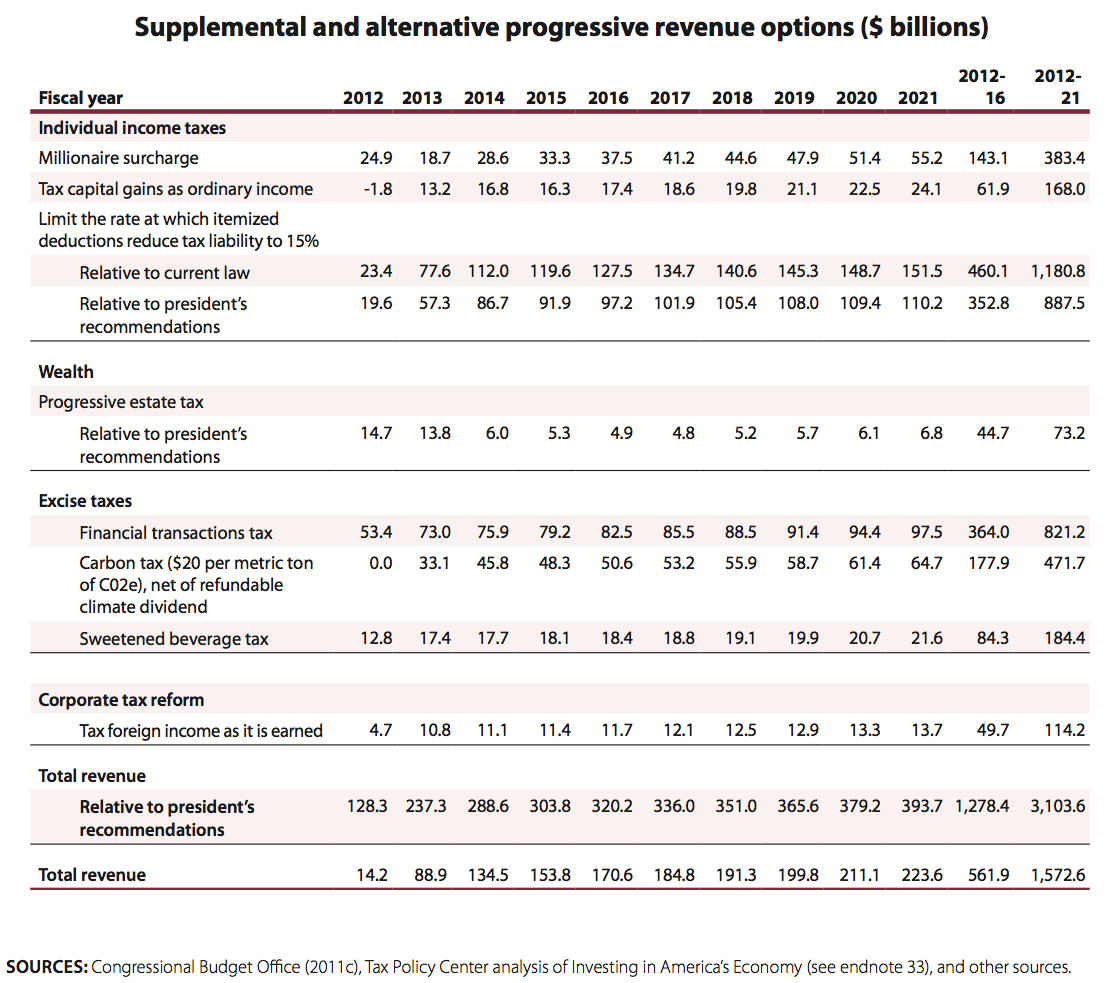

This brief also identifies eight progressive revenue policies that could complement the president’s recommendations and principles for tax reform. Collectively, these policies would also return revenue levels roughly to those scheduled under current law. These policies and their associated revenue relative to the president’s recommendations (over 2012-21) include:

- enacting a millionaire surcharge ($383 billion);

- taxing capital gains as ordinary income ($168 billion);

- further limiting the tax benefit of itemized deductions ($888 billion);

- enacting a progressive estate tax ($73 billion);

- enacting a financial speculation tax ($821 billion);

- enacting a cap-and-trade program and a refundable climate dividend ($472 billion);

- enacting a sweetened beverage tax ($184 billion); and

- ending the deferral of foreign corporate income ($114 billion).

Severe drawbacks of a spending-cuts-only approach to deficit reduction

The Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction is charged with negotiating a plan to reduce federal deficits by at least $1.5 trillion over the next 10 years. It is essential for the long-term health of the nation and the economy that its proposals include equitable amounts of increased revenue. The Budget Control Act (BCA) of August 2011, which mandated the creation of the committee, has already reduced budget deficits by $895 billion over the next decade by focusing strictly on the spending side of the ledger. Statutory spending caps will reduce discretionary outlays by $756 billion, program integrity and education provisions will cut $5 billion in net spending, and debt service will fall by $134 billion (CBO 2011a). Moreover, these cuts build on the spending cuts in the 2011 full-year appropriations bill, which lowered the trajectory for discretionary outlays by $122 billion over the next decade (CBO 2011b). Relative to the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) higher baseline for discretionary spending, the BCA cuts to discretionary outlays total $992 billion, or $1.2 trillion when debt-service savings are included (OMB 2011a).

A spending-cuts-only approach to deficit reduction is unacceptable for numerous reasons:

- Deep cuts to spending programs will defund key public investments and undermine economic security programs.

- Without more revenue, spending cuts will disproportionately fall on lower-income and working families.

- Spending cuts are more damaging to the economic recovery than tax increases, particularly tax increases on upper-income households.

- Tax policies of the last decade are responsible for much of the structural budget deficit and roughly half of debt accumulation over the last decade (Fieldhouse and Pollack 2011).

At the same time that tax policy was adding to the deficit, income and wealth have accrued disproportionately to high-income individuals, and tax policy over the last decade has reinforced these trends. Thus, relatively modest tax proposals aimed at the top can generate large sums of revenue (Fieldhouse and Shapiro 2011), potentially exceeding the Joint Select Committee’s deficit reduction mandate. Evenly splitting the primary budget savings (excluding net interest) required by the BCA between spending cuts and revenue increases would require roughly $1 trillion in revenue from the Joint Select Committee’s recommendations to match the roughly $1 trillion in spending cuts already enacted.1

In his recommendations to Congress for the Joint Select Committee, the president is seeking near-term job creation measures and long-term deficit reduction that exceed the committee’s mandate. The recommendations propose that Congress undertake comprehensive tax reform to raise $1.5 trillion over the next decade. This new revenue and the $1.2 trillion in spending cuts from the first phase of the BCA would meet the Joint Select Committee’s mandate, but are also coupled with $1.1 trillion from capping funding for Overseas Contingency Operations, $320 billion from health savings, $257 billion from other mandatory savings, and an additional $436 billion in debt-service savings. The president also proposed the American Jobs Act, a package of tax cuts ($254 billion) and job creation spending ($193 billion) frontloaded for 2012 and 2013, as well as offsets for its $447 billion cost. Net of the American Jobs Act, the president’s recommendations represent $3.2 trillion in new savings and $4.4 trillion in savings with the spending cuts from the first phase of the BCA, relative to OMB’s Budget Enforcement Act (BEA)–adjusted baseline.2 For the contingency that Congress fails to overhaul the tax code, the recommendations also propose $1.6 trillion in specific revenue policies as a backstop, including $479 billion in offsets for the American Jobs Act.3

This issue brief analyzes the revenue proposals in the president’s recommendations for the Joint Select Committee and offers a menu of alternative or supplemental progressive revenue options to reduce the deficit and/or finance job creation initiatives.

Policies are scored relative to a current law baseline, with the exception of the repeal of the upper-income Bush-era tax cuts and the reinstatement of the estate tax at 2009 parameters; these are scored relative to OMB’s BEA-adjusted baseline. Regardless of what baseline the joint committee uses, any of the policies discussed in this memorandum could be constructed to be scored as revenue positive. Under a current law baseline, for instance, the repeal of the Bush-era rates for top brackets could be constructed as a “surcharge” in order to achieve a revenue-positive score for the Joint Select Committee. Repeal would then be accomplished by (1) adding a surcharge through the Joint Select Committee process, and then (2) holding a separate vote to extend all the Bush-era cuts outside the committee process.4 All revenue scores exclude associated debt-service savings. For the purpose of this brief, interaction effects (i.e., the combined effect of two proposals may be greater or less than the sum of their parts) are ignored as well, including those with the alternative minimum tax. However, any final plan will obviously need to be estimated taking into account various interactions.

The president’s recommendations for the Joint Select Committee

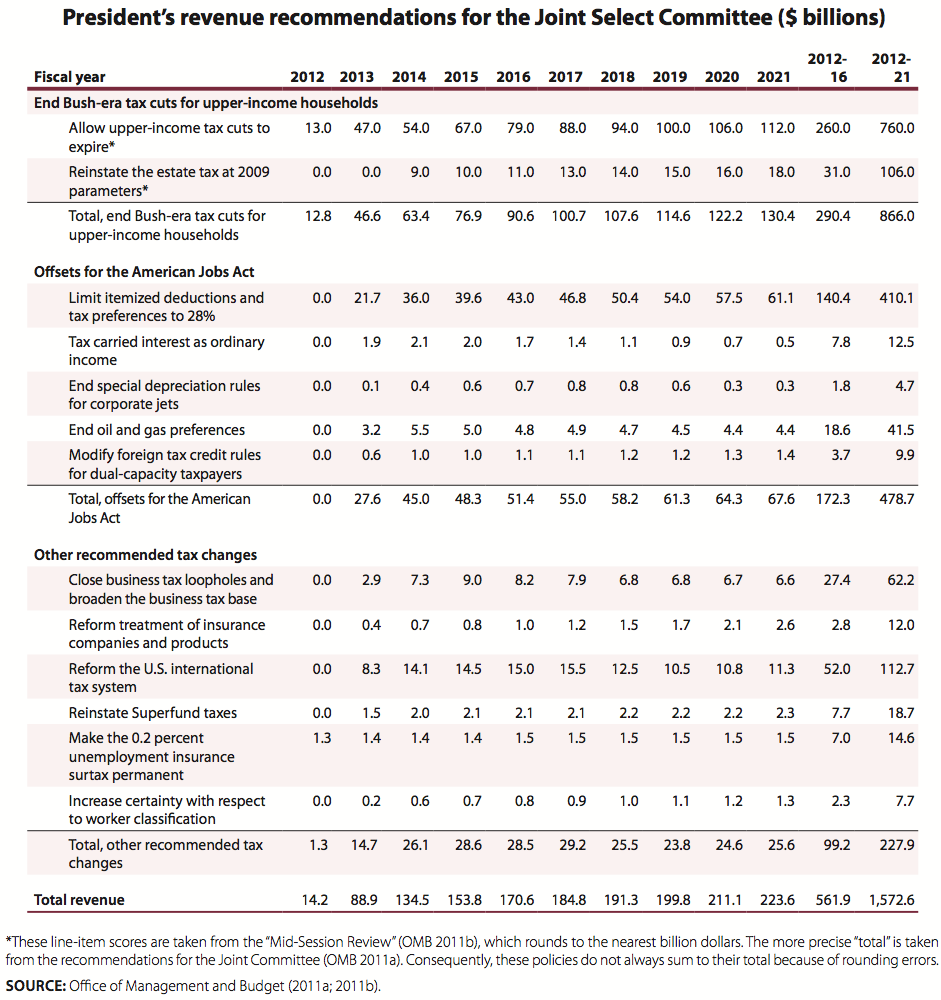

The president offered a comprehensive backup plan to raise $1.6 trillion should Congress fail to raise $1.5 trillion through comprehensive tax reform. Roughly half of this revenue ($760 billion) would come from allowing the Bush-era tax cuts to expire for households earning more than $250,000. The estate tax would also be reinstated at 2009 exemptions and rate.5 The proposed offsets for the American Jobs Act make up another $479 billion, including $410 billion from capping the value of tax expenditures for upper-income households, nearly $13 billion from eliminating the carried-interest loophole, and over $41 billion from eliminating tax carve-outs for the oil and gas industries. Closing other business loopholes (such as those related to inventory accounting), reforming the international tax system, and reinstating Superfund taxes for toxic waste cleanup account for most of the remaining $228 billion of revenue (see Table 1).

End Bush-era income tax cuts for upper-income households

Under current law, all the Bush-era tax cuts and temporary estate and gift tax provisions expire December 31, 2012; extending these provisions would cost $3.8 trillion over the next decade, net of maintaining the AMT patch and including associated debt service.6

The president’s budget requests and his recommendations to the Joint Select Committee have proposed repealing the Bush-era tax cuts for individuals with adjusted gross incomes exceeding $200,000 ($250,000 for joint filers). Repealing the 33 percent and 35 percent tax brackets, reinstating the personal exemption phase-out (PEP) and the limitation on itemized deductions (Pease), and ending capital gains and dividends tax cuts for these tax filers would save $760 billion over 2012-21 relative to current tax policies.7 These proposals would increase tax liability for only 1.9 percent of households, again relative to current tax policies (TPC 2011a), and over half of the tax changes would fall on the highest-income 0.1 percent of households with earnings of roughly $3.0 million or more.8 The president’s budget would expand the range of the 28 percent bracket to $200,000 in adjusted gross income (AGI) ($250,000 for joint filers), from $174,000 ($212,000 for joint filers) in 2011, and maintain the Bush-era tax cuts for earners below this threshold.

Reinstate the estate tax at 2009 parameters

The president’s budget requests and his recommendations to the Joint Select Committee have also proposed reinstating the estate tax at 2009 parameters. After gradually increasing the estate tax exemption to $3.5 million ($7 million for married couples) from a scheduled $1 million ($2 million for married couples) and reducing the marginal rate from 55 percent to 45 percent, the Bush-era tax cuts totally eliminated the estate tax in 2010. As part of last December’s Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance, and Job Creation Act, the estate tax was reinstated for 2011-12 at a record exemption of $5 million ($10 million for married couples) and a rate of only 35 percent, the lowest since 1931 (Jacobson, Raub, and Johnson 2011). Reinstating the estate tax at its 2009 parameters ($3.5 million exemption and 45 percent rate) would generate $106 billion over 2013-21 relative to current tax policies while leaving 99.75 percent of all estates fully exempt from taxation (Marr and Levitis 2009).9

Implement offsets for the American Jobs Act

The administration proposed $479 billion of new revenue to more than offset the $447 billion cost of the American Jobs Act. The largest component, which would impose a new limit on the value of tax expenditures for upper-income households, would raise $410 billion. The other offsets include $13 billion from ending the carried interest loophole for investment income, $5 billion from ending special depreciation treatment for corporate jets, $41 billion from ending subsidies to oil and gas companies, and $10 billion from modifying tax rules for dual-capacity taxpayers. These changes would not impact the vast majority of taxpayers. The top 1 percent of earners (with incomes above $593,000) would absorb 66 percent of the incidence, while the top 5 percent of earners would bear 95 percent of these changes, relative to current law (TPC 2011b). The offsets are spread over nine years, with 64 percent of the revenue raised in the latter half of the next decade, when the economy should be stronger. These tax offsets are targeted toward high-income individuals (with relatively low marginal propensities to consume) and profitable businesses, and would be expected to have a lesser impact on near-term economic growth than just about any other offset, short of higher taxes above even higher levels of income (Fieldhouse and Shapiro 2011).

Limit the rate at which tax preferences reduce tax liability for upper-income households.

The president’s recommendations for the Joint Select Committee proposed limiting the value of itemized deductions as well as specified above-the-line deductions and exclusions for upper-income households as an offset for the American Jobs Act (OMB 2011c). The changes would raise $410 billion over 2013-21. Currently, the value of exclusions and above-the-line deductions increases with a tax filer’s marginal tax rate, as is the case for itemized deductions for the 36 percent of filers who itemize (CBO 2011c). This proposal would limit to 28 percent the rate at which these tax expenditures reduce tax liability for tax filers above the 28 percent bracket, a tax change affecting only 2.2 percent of tax filers—those with incomes above $174,400 ($212,300 for joint filers)—relative to current law (TPC 2011c).10 Specified above-the-line deductions include those relating to health insurance costs of the self-employed, income attributable to domestic production activities, moving expenses, Archer Medical Savings Accounts, health savings accounts, interest on education loans, and higher education expenses. Specified exclusions include tax-exempt interest on state and local bonds, the employer-sponsored health insurance exclusion, and the foreign earned-income exclusion. This policy would make many tax expenditures less regressive while maintaining incentives embedded in the tax code. (The president’s 2012 budget previously proposed limiting the rate at which itemized deductions reduce tax liability to 28 percent, for savings of $293 billion over 2012-21.11)

Tax carried interest as ordinary income.

Rather than pay the corporate income tax, business partnership income flows through to the partners, who must report their business income as individual income. This organizational structure bypasses the double taxation of business income (corporate taxes followed by capital gains and dividends taxes when after-tax corporate profits are disbursed to shareholders). Some partnerships receive a stake in future profits, referred to as carried interest, which is taxed at the 15 percent preferential tax rate on capital gains and dividends. The president’s recommendations to the Joint Select Committee proposed taxing carried interest from investment partnerships as ordinary income, a step that would raise $13 billion over 2013-21. In his call on Washington to rebalance taxes for the super-rich, Warren Buffett cited the carried interest loophole as one of the extraordinary tax breaks that lower some millionaires’ and billionaires’ effective tax rates below that of middle-class households (Buffett 2011). The president’s 2012 budget also proposed taxing carried interest as ordinary income.

End special depreciation rules for corporate jets.

Businesses can depreciate the cost of commercial passenger and freight aircraft over seven years. The cost of noncommercial jets, including corporate jets, however, can be depreciated over five years. The president’s recommendation to end the preferential depreciation schedule for corporate jets would raise $5 billion over 2013-21.12

Eliminate oil and gas preferences.

The president’s budget requests have repeatedly proposed eliminating a handful of tax preferences carved out over the years for fossil fuel producers. Eliminating this tax code spending would help level the playing field between renewable energy sources and fossil fuels. The president’s recommendation to end these oil and gas subsidies would raise $41 billion over 2013-21. Specifically, the policy would repeal percentage depletion for oil and natural gas wells, domestic manufacturing deductions for oil and natural gas companies, the expensing of intangible drilling costs, the deduction for tertiary injectants, the exception to passive loss limitation for working interests in oil and natural gas properties, and the preferential two-year amortization for independent producers’ geological and geophysical expenditures (the amortization period would rise to seven years).13

Modify rules for dual-capacity taxpayers.

The president’s recommendations to the Joint Select Committee propose modifying foreign tax credit rules for dual-capacity taxpayers—multinational companies that both pay foreign taxes and receive benefits from the government levying those taxes. Most dual-capacity taxpayers are foreign subsidiaries of U.S.-based oil, gas, or mineral companies. This change was previously proposed as a reform to the U.S. international tax system in the president’s 2012 budget and would raise $10 billion over 2013-21.14

Other tax changes recommended by the administration

The president’s recommendations to the Joint Select Committee also propose a handful of other tax reforms, including eliminating business tax loopholes, reforming the treatment of insurance companies and products, reforming the international tax code, reinstating Superfund taxes, and making permanent the unemployment insurance surtax. Collectively, these tax reforms are projected to save $228 billion over 2012-21.

Close business loopholes and broaden the business tax base.

The president’s recommendations to the Joint Select Committee propose repealing inventory accounting preferences and tax preferences for the coal industry, a step that would raise $62 billion over 2012-21. Specifically, the recommendations would repeal last-in, first-out (“LIFO”) inventory accounting, for savings of $52 billion over 2012-21;15 repeal lower-of-cost-or-market inventory accounting, for savings of $8 billion;16 and eliminate preferences for the coal industry (including the ability to expense exploration and development costs, percentage depletion for coal and hard mineral fossil fuels, capital gains treatment for royalties, and a domestic manufacturing deduction for coal and other hard mineral fossil fuels), for savings of $2 billion.

Reform treatment of insurance companies and products.

The president’s recommendations to reform tax rules for life insurance companies and their products would raise $12 billion over 2013-21. New rules would require more information reporting for the sale of life insurance contracts and benefits paid. Dividends-received deductions for life insurance companies would be modified and streamlined along the lines of those for non–life insurance companies. Lastly, the administration would expand pro rata interest expense disallowance for corporate-owned life insurance (repealing the exception for officers, directors, and employees).17

Reform the U.S. international tax system.

The president’s recommendations to reform U.S. international tax rules would raise $113 billion over 2013-21. Deferring the deduction of interest expense related to deferred income would save $36 billion.18 Determining the foreign tax credit on a pooling basis (on the consolidated earnings and foreign taxes paid by all subsidiaries of a multinational corporation) would save $53 billion. Taxing excess returns associated with transfers of intangibles offshore would generate $19 billion.19 Clarifying tax rules to limit shifting of income through intangible property transfers would generate $1 billion. Limiting earnings stripping by expatriated entities (limiting the deductibility of interest paid so U.S. firms could not inappropriately reduce tax liability from U.S. operations) would generate $4 billion.20 All of these proposals were previously included in the president’s budget request.21

Reinstate Superfund taxes.

The president’s recommendation to reinstate Superfund taxes would raise $19 billion over 2013-21. The Environmental Protection Agency’s Superfund program was once predominantly funded by dedicated taxes, but it is now largely funded by general revenue. A stable source of funding would allow for better planning for multiyear hazardous chemical waste cleanup than reliance on year-to-year appropriations. This policy would re-impose an excise tax of 9.7 cents per barrel of crude or refined petroleum, an excise tax of $0.22 to $4.87 per ton on various chemicals, and a corporate environmental income tax of 0.12 percent on corporations’ modified AMT income exceeding $2 million.

Reinstate the unemployment insurance surcharge.

The federal unemployment insurance tax on employers reverted from 0.8 percent to 0.6 percent on June 30, 2011. The president’s 2012 budget recommended reinstating the higher 0.8 percent UI surcharge, which would generate $15 billion over 2012-21.

Increase certainty with respect to worker classification.

Misclassifying an employment relationship, particularly treating employees as independent contractors, can reduce an employer’s tax liability. The president’s recommendation to permit the IRS to issue guidance about worker classification and require reclassification of all misclassified workers would raise $8 billion over 2013-21.

Distributional impact of the president’s recommendations

Based on distributional analysis by the Tax Policy Center, the president’s recommendations for the Joint Select Committee would raise revenues from high-income individuals while reducing or leaving unchanged taxes for the vast majority of taxpayers. Relative to current tax policy, over 95 percent of all the tax increases would be borne by the highest-income 5 percent of households—those with incomes above $227,000 (TPC 2011d).22 Millionaires would bear over two-thirds of the tax changes; their effective tax rates would rise 5.5 percentage points to 38.4 percent (TPC 2011e).23 At the same, the tax provisions of the American Jobs Act would, on average, slightly lower taxes for the bottom 60 percent of earners—those with income below $65,000 (TPC 2011d). Relative to current law (i.e., all the Bush-era tax cuts expire on schedule), however, households earning less than $1 million would, on average, receive a tax cut. Households with over $1 million in income would see an average tax increase of $29,000, raising their effective tax rate by 0.9 percentage points relative to current law (TPC 2011f). In light of the transfer of wealth to upper-income households through the tax policies of the last decade, this modest increase seems appropriate. In 2010, households with over $1 million in income received on average $168,000 from the 2001-08 tax cuts (TPC 2008a), lowering their average tax rate by 5.1 percentage points, all of which was deficit financed.

Supplemental and alternative progressive revenue options

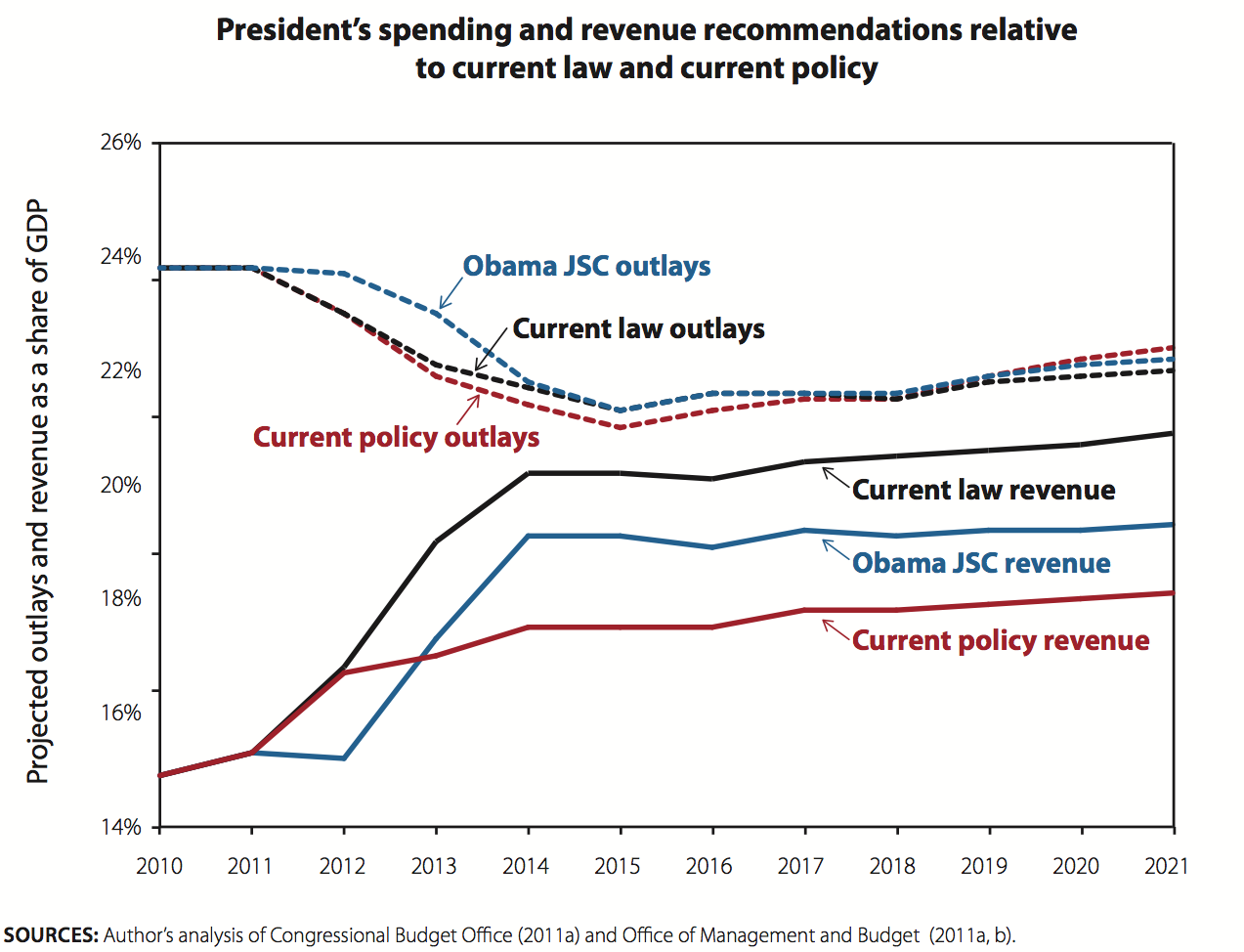

The president’s recommendations represent significant deficit reduction relative to a current policy baseline (see Figure A). The current policy baseline (as opposed to the current law baseline) assumes that the scheduled reduction in Medicare physician payments is prevented (i.e., the “doc fix” is maintained), overseas contingency operations (OCO) are wound down,24 the 2001 and 2003 income tax cuts are continued, the 2011-12 estate and gift tax cuts are continued, the 2011 parameters of the AMT are indexed for inflation, and the business tax extenders (routinely extended credits such as the research and experimentation credit) are continued.25 The president’s recommendations would reduce outlays roughly to current law levels in 2014 and below projected levels under current policy in 2020. (In the near-term, the OCO spending adjustment drives current policy outlays below current law outlays. In the long term, the “doc fix” and the additional debt service resulting from deficit-financed tax cuts drive current policy outlays above current law outlays.) The BCA has already reduced outlays by $2.1 trillion under both current law and current policy (CBO 2011b).

The revenue levels in the president’s recommendations, while an improvement relative to current policy, fall well below revenue levels scheduled under current law. Revenue levels in the president’s recommendations rise $2.0 trillion above current policy revenue levels but $2.7 trillion below current law revenues over 2012-21. While the president’s recommendations largely reflect current policies, they ignore the $751 billion in lost revenue that would arise from maintaining the business tax extenders (CBO 2011a), and so the gap below current law is even larger.26 Adjusting the revenue levels in the president’s recommendations for the likely continuation of the business tax extenders, the president’s recommendations for the joint committee are more accurately stated as $3.4 trillion below current law and $1.3 trillion above current policy. (The payroll tax and business expensing provisions of the American Jobs Act reduce the net impact below the $1.5 trillion range.) By 2021, the revenue gap between current law and the president’s recommendations is a sizeable 1.5 percentage points of GDP.

Even with the revenue increases proposed in the president’s recommendations, revenue inadequacy is a prime driver of budget deficits. At minimum, Congress would need to find revenue offsets for the business tax extenders if the president’s recommendations are adopted. Even greater levels of new revenue would be appropriate for financing additional job creation and/or for further deficit reduction. What follows is a menu of alternative or supplemental revenue options that the Joint Select Committee could incorporate into job creation and deficit reduction measures (see Table 2).

Adjust the individual income tax code.

The president’s recommendations outlined principles for tax reform, including the “Buffet Rule” that middle-class Americans shouldn’t be paying a higher tax rate than some millionaires. The president’s proposed tax policies would make the tax code more progressive, but the Buffet Rule would not necessarily be satisfied because the preferential treatment of capital income is only partially addressed.27 There are also ways to increase the progressivity of the federal tax code beyond aligning the tax treatment of work income and investment income. The income cutoff for married joint filers in the highest tax bracket has fallen precipitously, from roughly $3 million in the early 1950s (adjusted to current dollars) to $1 million in 1970, to $379,000 today.28 The top marginal tax rate applied above that top income cutoff has fallen precipitously as well, from just over 90 percent in the 1950s, to 70 percent in the 1970s, to 50 percent in the mid-1980s, and to 35 percent for most of the past decade (TPC 2011h). The share of taxes paid by the top 1 percent of households (by income) has increased as pre-tax income gains have gone disproportionately to upper-income earners, but effective federal tax rates—a better measure of overall progressivity—have fallen from 37.0 percent for the top 1 percent in 1979 to 29.5 percent in 2007 (CBO 2010). For a broader discussion of why it is appropriate to ask the highest-income households to contribute more in taxes, see Fieldhouse and Shapiro (2011).

Add a millionaire surcharge.

Adding a 5.4 percent surcharge on modified adjusted gross incomes above $1 million ($2 million for joint filers), effectively creating a top rate of 45.9 percent,29 would raise $383 billion over 2012-21 relative to current law.30 This policy would also raise the effective rate on capital gains to 29.2 percent.31 A millionaire surcharge establishing a top tax rate of 45.9 percent would still keep the top tax rate below its levels from 1932 to 1986 (TPC 2011h). A surcharge on AGI above $500,000 ($1 million for joint filers) was proposed in an early version of the 2010 health care reform bill, and would have raised $544 billion over a decade (JCT 2009a). In the enacted version, the proposal was replaced with a more modest surcharge on investment and earned income that raised $210 billion over a decade (JCT 2009b).

Similar revenue levels could be produced through a so-called Super Pease surcharge—limiting the value of itemized deductions for households with income above $500,000 ($1 million for joint filers). Pease, or the limitation on itemized deductions, was phased out by the Bush-era tax cuts and eliminated in 2010. The president’s budget proposed reinstating Pease for upper-income households. If reinstated for 2013, Pease will limit itemized deductions by 3 percent of AGI above $174,450 (for both single and joint filers). Under current law, the Pease limitation is capped at 80 percent of all itemized deductions. A Super Pease surcharge would reduce the value of itemized deductions by a flat rate, say 5 percent, for all AGI above the surcharge cutoff. There would be significant interaction effects between this proposal and the limitation on the rate at which itemized deductions reduce income tax liability, but parameters could be adjusted to achieve the desired revenue level.

Tax capital gains as ordinary income, up to a top rate of 28 percent.

Taxing capital gains as ordinary income up to a top rate of 28 percent (the top rate on capital gains set by the 1986 tax reforms enacted by President Reagan), up from 15 percent in 2012 and 20 percent in 2013, as scheduled under current law,32 would generate $168 billion over a decade relative to an adjusted current-policy baseline.33 Repealing the preferential treatment of capital gains, which are taxed at much lower rates than income earned through work, would raise significant revenue while leaving most tax filers unaffected. More than 83 percent of the tax would fall on the top 1 percent of earners, and 92 percent of Americans would see no increase in their taxes (TPC 2008b).34 Qualified dividends would still be taxed as ordinary income starting January 1, 2013, as scheduled under current law.35 There would be significant interaction effects between this policy and a millionaire surcharge. Similarly, ending this policy would wipe out most savings otherwise anticipated from taxing carried income as ordinary income.

Limit the rate at which itemized deductions reduce tax liability to 15 percent.

Extending the limitation on the rate at which itemized deductions reduce tax liability to include filers in the 25 percent and 28 percent brackets, as well as the top two brackets, would raise $1.2 trillion over 2012-21, relative to current law (CBO 2011c). Roughly one-third of taxpayers itemize deductions, and only one in four of all taxpayers would be affected by capping the benefit of those deductions at 15 percent (CBO 2011c). Relative to limiting the benefit of itemized deductions to 28 percent, as was proposed in the president’s recommendations for the joint committee, this broader restriction would raise an additional $888 billion over the next decade. Even more revenue could be raised if the 15 percent limitation on itemized deductions was extended to specified above-the-line deductions and exclusions.

Restore and strengthen the estate tax.

The estate tax, the only federal tax on concentrated wealth and the most progressive federal tax, was eviscerated by the Bush-era tax cuts (Fieldhouse and Pollack 2011). Wealth is even more concentrated at the top of the wealth distribution than income is concentrated among the highest-earners, and the ratio of wealth held by the top 1 percent relative to median wealth hit a record 225 in 2009 (Fieldhouse and Shapiro 2011). Reinstating the estate tax at 2009 parameters represents an improvement over the higher exemption and lower rate set by the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance, and Job Creation Act of 2010, but the 2009 parameters are so generous compared with current law that doing so will cost $239 billion (JCT 2011a).

Enacting Senator Bernie Sanders’ (I-Vt.) Responsible Estate Tax Act (S. 3533) would be one way to revitalize the estate tax and make the federal tax code more progressive. Like the president’s recommendations to the Joint Select Committee, this policy would include a $3.5 million exemption ($7 million for married couples), leaving 99.75 percent of all estates fully exempt. The taxable portion of estates beyond these exemptions would be subject to a progressive series of marginal tax rates as follows: a 45 percent rate up to $10 million; a 50 percent rate up to $50 million; a 55 percent rate up to $500 million; and a 65 percent rate on the portion of estates worth over $500 million (Sanders 2010). Effective tax rates would be much lower than the top marginal rate. Relative to the president’s recommendations to the Joint Select Committee, this progressive estate tax would raise $73 billion over 2012-21.36

Tax financial transactions and speculation.

Beyond taxing work and investment, the government levies many corrective excise taxes on goods so they reflect the goods’ truer societal costs (externalities). Cigarettes, alcohol, and gasoline, among other goods, are all taxed to reflect their negative social externalities. Intuitively, taxing that which is harmful is better than taxing productive things, like work and savings. Obvious opportunities abound to expand corrective excise taxes, be they to dampen speculative financial trading, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, or improve health outcomes from the foods we consume.

Small taxes on transactions of exotic financial products have the potential to raise large sums of revenue while dampening speculative trading and encouraging more productive investment. The federal government collected general revenue from a stock transfer tax and issuance tax from 1914 to 1966, and a small tax on share issuance and transfers is still in place to finance the operations of the Securities and Exchange Commission (Pollin, Baker, and Schaberg 2002). The United Kingdom still levies a stamp duty on stock issuance and trades, and the European Union is moving toward a uniform financial transactions tax; the European Parliament passed such a tax earlier this year, and legislation is pending before the European Commission (Aldrick 2011).37 Taking behavioral responses into consideration, the Tax Policy Center recently estimated that financial transactions taxes could raise $821 billion over 2012-21.38 The specified financial transactions tax base was set to tax stock transactions at 0.25 percent, bond transactions at 0.004 percent, option premiums at 0.25 percent per year to maturity, foreign exchange transactions at 0.004 percent, and futures and swaps at 0.01 percent. (Rates are set on a range of financial assets to minimize tax arbitrage opportunities.)

Price carbon.

Pricing carbon through either a carbon tax or the auctioning of permits would reduce the emission of greenhouse gases, widely believed to be causing global warming, and also yield tens of billions of dollars (or more) annually. A cap-and-trade program would either allocate and/or auction permits to “upstream” energy producers (such as electrical power plants or oil refineries), whereas a carbon tax would tax energy consumption based upon the carbon content of the fuel. This proposal would enact a cap-and-trade program to limit carbon emissions, although a direct carbon tax could be designed to generate the same amount of revenue. CBO estimates a cap-and-trade program with an allowance price of $20 in 2012 that grows at 5.6 percent annually would generate $1.2 trillion in revenue and reduce CO2 emissions 20 percent by 2025 and 50 percent by 2050 (CBO 2011c).

Without other changes, pricing carbon would be regressive, since low-income consumers spend a greater share of their income on carbon-intensive energy such as gasoline and heating fuel. To correct for higher energy prices, a significant portion of the revenue from carbon abatement should be reserved to compensate low- and middle-income households. The Tax Policy Center estimated that a cap-and-trade program with the parameters specified above would reduce the deficit by $471 billion over 2013-21, net of a targeted carbon dividend rebating roughly 55 percent of total revenue.39 The refundable climate dividend was $161 for one person and $49.50 per additional person in the tax unit. The credits are phased out for incomes between $70,000 and $110,000 for joint filers and between $30,000 and $50,000 for non-joint filers (earnings or AGI, whichever is higher).

Impose a sweetened beverage excise tax.

A one cent per ounce excise tax, beginning in 2012, on the manufacture and importation of beverages sweetened with sugar or high-fructose corn syrup, would raise $184 billion over 2012-21, according to the Tax Policy Center.40 In addition to raising revenue, the tax is likely to result in improved health outcomes and reduce national health care expenditure.

Tax corporate foreign income as earned.

The president’s recommendations identified a number of corporate tax loopholes that could be eliminated to broaden the tax base and raise more revenue. One of the president’s principles for tax reform—that of increasing job creation and growth in the United States—demands that more is done to overhaul the corporate tax to end preferences that encourage the offshoring of American jobs.

The tax deferral on earnings from U.S.-controlled foreign subsidiary corporations enables firms to indefinitely avoid repatriating foreign earnings, because firms are taxed only when foreign earnings are received by the U.S. parent company as dividends. The deferral of income from U.S.-controlled foreign subsidiary corporations could be eliminated and all foreign earnings would be taxed as earned, thereby decreasing tax arbitrage opportunities arising from low-tax countries that encourage foreign rather than domestic investment and employment. Foreign tax credits (which reduce U.S. tax liability by the amount of tax paid to foreign governments) would still be allowed, although the credit limits would be treated differently. The U.S. parent corporation would no longer split domestic and foreign expense activities, so the credit would be allowed only against tax liability to foreign governments. Additionally, because all earnings would be treated identically, the differentiation between active and passive foreign income would no longer matter (the “active financing” exception for U.S.-controlled foreign financing subsidiaries would be closed). According to the CBO, ending the tax deferral would generate $114 billion over 2012-21 (CBO 2011c). There would be significant interaction effects between this policy and the president’s proposals to reform the U.S. international tax system and to modify foreign tax credit rules for dual-capacity taxpayers.

Supplemental progressive revenue options in context

Some combination of these policies could be used to finance additional job creation and deficit reduction measures. Alternatively, some combination could also be used to offset the extension of the routine business tax breaks, totaling $751 billion over the period, that are not incorporated into the president’s recommendations to the Joint Select Committee. Combining all of these policies would raise $3.1 trillion over 2012-21 (excluding various interaction effects) relative to the president’s recommendations to the Joint Select Committee, bringing projected revenue roughly in line with current law revenue levels. By contrast, the president’s recommendations alone fall $3.4 trillion shy of current law revenue projections over the next decade when adjusting for the business tax extenders (or $3.2 trillion short without the tax cuts in the American Jobs Act). Finally, any policies that produce additional revenue will lower the trajectory for spending as a result of lower debt service costs, which are ignored in all revenue proposals.

For a more comprehensive set of tax policies and reforms to restore revenue adequacy, see Investing in America’s Economy, a progressive long-term approach to strengthening the economy, rebuilding the American middle class, and stabilizing debt as a share of the economy (OFS 2010).

Endnotes

- The first phase of the Budget Control Act produced $761 billion in primary spending cuts, building on $122 in spending cuts initiated by the 2011 full-year continuing resolution (CBO 2011b). To avoid triggering sequestration, the Joint Select Committee must achieve $1.2 trillion in total savings, 18 percent of which is assumed to be reduced debt service and 82 percent ($984 billion) primary savings. Applying the same formula for debt service savings to the Joint Select Committee’s target of $1.5 trillion in deficit reduction, primary budgetary savings would be on the order of $1.2 trillion. Total primary budgetary savings would range from $1.7 trillion to $2.0 trillion, depending on whether the committee just barely avoids sequestration or actually meets its $1.5 trillion mandate. If half of the primary savings from the BCA were to come from revenue, the Joint Select Committee would need to include between $873 billion and $1.0 trillion of revenue in its recommendations. Targeted primary savings and new revenue would rise if the Joint Select Committee includes a jobs package and associated budgetary offsets in its proposals, or if the Joint Select Committee seeks to exceed its mandate.

- OMB’s BEA-adjusted baseline is a current policy baseline assuming that the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts are extended, the estate tax is maintained at 2011-12 parameters, the alternative minimum tax (AMT) is indexed for inflation, a scheduled reduction in Medicare physician payments is prevented (i.e., the “doc fix” is maintained), the maximum Pell Grant is fully funded, and a placeholder for disaster relief is assumed ($86 billion over 2012-21). See OMB (2011b).

- These scores are measured relative to OMB’s BEA-adjusted baseline (see OMB 2011b). Relative to CBO’s August 2011 baseline (see CBO 2011a), the president’s recommendations to the joint committee would generate $1.5 trillion in revenue (OMB 2011a).

- For instance, the increase of the top marginal rate from 35 percent to 39.6 percent could be replicated with a 4.6 percent surcharge on earned income. Similarly, a 5 percent surcharge on capital gains and dividends income would replicate allowing the capital gains and dividends rates from 15 percent to 20 percent. Constructing surcharges for reinstating Pep, Pease, and the estate tax at 2009 parameters would be more complex but an approximation is feasible.

- These first two policies are scored relative to OMB’s BEA-adjusted baseline. See endnote 2.

- The cost of extending these tax cuts without accounting for the AMT would be $2.9 trillion (including debt service), but this ignores a large interaction effect. By lowering income tax liability without adjusting the AMT accordingly, the Bush-era tax cuts pushed many more tax filers into the AMT, thereby increasing the cost of the annual AMT patch (which intentionally keeps tax filers out of the AMT). Extending expiring income tax, estate and gift tax, and AMT provisions would reduce revenue by $3.9 trillion, with an additional $698 billion in debt service. The cost of just extending the AMT is $690 billion, with an additional $119 billion in debt service (CBO 2011a). Net of this AMT patch, extending the Bush-era tax cuts would decrease revenue by $3.3 trillion over 2012-21 and increase debt service by $579 billion.

- Revenue estimates from OMB’s 2012 “Mid-Session Review” (OMB 2011b). See Table S-2, p. 25.

- Tax Policy Center distributional analysis is measured relative to current policy, in terms of tax units for tax year 2013. The income break for the top 0.1 percent is measured in 2009 dollars (TPC 2011a).

- Revenue estimates from OMB’s 2012 “Mid-Session Review” (OMB 2011b). See Table S-2, p. 25.

- Tax Policy Center distributional analysis is measured relative to current law, in terms of tax units for tax year 2013. Under current law, the 28 percent tax bracket would not be expanded to $200,000 ($250,000 for joint filers), as proposed in both the president’s budget and the framework for the Joint Select Committee. The current law income break for the 28 percent bracket is presented for tax year 2011 in 2011 dollars. Tax policies limited to those earning above $200,000 ($250,000 for joint filers) would only affect 1.9 percent of households (TPC 2011a)

- Revenue estimates from JCT (2011a). See Provision XI, p. 12.

- The accelerated depreciation schedule defers taxation to later years when the net present value of tax liability is lower.

- See OMB (2011a, 48), OMB (2011d, 204), and JCT (2011b, 336) for a comprehensive discussion of the administration’s proposals.

- See JCT (2011b, 267-69) for a comprehensive discussion of the proposed modification to dual capacity taxpayer rules and OMB (2011c, 153) for legislative text of the proposal.

- LIFO accounting sets the cost of inventory sold equal to the cost of the most recently purchased or produced inventory. The value of inventory rises with some goods, such as wine; sold inventory would instead be accounted for at present value. See JCT (2011b, 300-03) for a comprehensive discussion of the administration’s proposals.

- Businesses would no longer be allowed to take the cost-of-goods-sold deduction before merchandise is sold. See JCT (2011b, 333-35) for a comprehensive discussion of the administration’s proposals.

- See OMB (2011a, 49-50) and JCT (2011b, 274-94) for a comprehensive discussion of the administration’s proposals.

- Multinationals are currently able to deduct some of the interest cost related to deferred source income from controlled foreign subsidiaries not subject to U.S. taxation.

- Excessive transfer pricing of intangible assets to controlled foreign companies would be treated as Subpart F income subject to taxation regardless of whether income is repatriated.

- See OMB (2011a, 50-51) for a full explanation of the administration’s proposals.

- See JCT (2011b, 161-267) for a comprehensive discussion of the administration’s proposals to reform the U.S. international tax system.

- Tax Policy Center distributional analysis is measured relative to current tax policy, in terms of tax units in tax year 2013.

- The effective tax rate is calculated on payroll taxes, individual income taxes, corporate income taxes, and estate and gift taxes.

- CBO’s current law baseline assumes that supplemental OCO outlays grow with inflation (along with all discretionary spending). Under current policy, OCO follows the same path as in the president’s budget. Debt service is adjusted accordingly.

- The current policy baseline and recommendations for the Joint Select Committee are modeled from CBO’s August 2011 baseline (CBO 2011a), primarily using the budgetary effects of alternative policies from Table 1-8. See Tables S-3 and S-4 for the bridge between the president’s recommendations and CBO’s August 2011 baseline (OMB 2011a).

- The business tax extenders would also increase debt service by $159 billion over 2012-21, for a total cost of $920 billion.

- Even if the carried interest loophole is eliminated, the 20 percent preferential rate on capital gains and qualified dividends (23.8 percent with the health care reform surcharges) would be well below the top marginal tax rates of 39.6 percent. Even curtailed deductions, exemptions, and exclusions can still decrease tax liability and top earners pay payroll taxes on only the first $106,800 in earned income. The capital gains rate is not a floor on effective tax rates: Of the 400 tax returns with the highest AGI in 2007, 152 paid effective tax rates below 15 percent (IRS 2011). Raising marginal rates on capital gains and qualified dividends back to 20 percent could still leave some middle-class households paying higher effective tax rates than some millionaire households.

- The income cutoffs for married joint filers in the top marginal tax bracket (TPC 2011g) have been adjusted to August 2011 dollars using CPI-U-RS.

- Modified adjusted gross income is defined as AGI reduced by any deduction allowed for investment interest (deductions not used in calculating AGI). This rate includes the 0.9 percent earned income surcharge from health care reform legislation and assumes the top marginal income tax rate adheres to current law. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (i.e., the 2010 health care reforms) broadened the Medicare hospital insurance tax base to include a 0.9 percent surcharge on earned income and a 3.8 percent surcharge on investment income for taxpayers with AGI above $200,000 ($250,000 for joint filers), which will take effect in 2013. The effective tax rate on capital gains for upper-income households is scheduled to rise to 23.8 percent in 2013.

- Revenue score is based on private Joint Committee on Taxation estimates provided by congressional staff.

- These rates include the 3.8 percent investment income surcharge from the Affordable Care Act.

- Taxing capital gains only up to a 28 percent rate would also require repealing the investment income surcharge from the Affordable Care Act.

- This estimate is based on the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center’s analysis of Investing in America’s Economy: A Budget Blueprint for Economic Recovery and Fiscal Responsibility, as adapted and independently scored for the Solutions Initiative and funded by the Peter G. Peterson Foundation. The Peterson Foundation convened organizations with a variety of perspectives to develop plans addressing the nation’s fiscal challenges. The American Enterprise Institute, the Bipartisan Policy Center, the Center for American Progress, the Economic Policy Institute, the Heritage Foundation, and the Roosevelt Institute Campus Network each received grants. All organizations had discretion and the independence to develop their own goals and propose comprehensive solutions. The Peterson Foundation’s involvement with this project does not represent endorsement of any plan. The final plans developed by all six organizations were presented as part of the Peterson Foundation’s second annual Fiscal Summit in May 2011. The TPC estimate of the capital gains provisions in the EPI plan was scored against a baseline that assumes that the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts expire, the middle-class tax relief in the president’s budget is reinstated, and the AMT patch is extended permanently and indexed to the consumer price index. This policy was also layered after replacing the Affordable Care Act investment income surcharge with a millionaire surcharge of 5.4 percent on AGI above $500,000 ($1 million for joint filers).

- Tax Policy Center distributional analysis is measured relative to then-current law, in terms of tax units for tax year 2007.

- The president’s 2012 budget proposed taxing qualified dividends at a preferential 20 percent rate, which would reduce revenue by $96 billion over 2012-21 (JCT 2011a).

- Relative to current law (in which estate tax exemptions and tax rates revert to pre-2001 law), the progressive estate tax would decrease revenue by $166 billion over 2012-21. This score is based on a Joint Committee of Taxation score of S. 3533 that was not made publicly available. The base policy would reduce revenue by $192 billion over 2010-20 and $199 billion over 2012-20. The revenue impact for 2021 is extrapolated by adjusting the 2020 revenue level for nominal GDP growth for a cost of $229 billion over 2012-21 relative to current law. Repealing the estate and gift tax cuts in December’s tax deal would increase revenue by $63 billion over 2012-21. Replacing the estate tax in the president’s framework (a revenue loss of $239 billion relative to current law) with the progressive estate tax would then generate $73 billion, relative to OMB’s BEA-adjusted baseline.

- The proposed tax would be equal to 0.05 percent of trades and is estimated to raise upwards of €200 billion ($275 billion) annually (Aldrick 2011).

- This estimate is based on the TPC analysis of Investing in America’s Economy, op. cit.

- Specifically, the cap-and-trade program is projected to raise $1.0 trillion over 2013-21, while the refundable tax rebate would simultaneously reduce revenue by $184 billion and increase direct spending by $388 billion. The refundable portion of tax credits are treated as direct spending in budget scorekeeping. This estimate is based on the TPC analysis of Investing in America’s Economy, op. cit. The TPC estimates of the cap-and-trade program in the EPI plan were scored against a baseline that assumes the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts expire, the middle-class tax relief in the president’s budget is reinstated, and the AMT patch is extended permanently and indexed to the consumer price index.

- This estimate is based on the TPC analysis of Investing in America’s Economy, op. cit.

References

Aldrick, Philip. 2011. “EU Parliament Approves Tobin Tax on Transactions.” London: The Telegraph, March 8. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/economics/8368563/EU-Parliament-approves-Tobin-tax-on-transactions.html

Buffett, Warren. 2011. “Stop Coddling the Super-Rich.” New York Times, August 14. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/08/15/opinion/stop-coddling-the-super-rich.html?_r=2

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2010. “Average Federal Tax Rates and Income, by Income Category (1979-2007).” Washington, D.C.: CBO. http://www.cbo.gov/publications/collections/collections.cfm?collect=13

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2011a. “The Budget and Economic Outlook: An Update.” Washington, D.C.: CBO, August 24. http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/123xx/doc12316/08-24-BudgetEconUpdate.pdf

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2011b. “CBO Analysis of August 1 Budget Control Act.” Letter to the Honorable John Boehner and the Honorable Harry Reid. Washington, D.C.: CBO, August 1. http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/123xx/doc12357/BudgetControlActAug1.pdf

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 2011c. “Reducing the Deficit: Spending and Revenue Options.” Washington, D.C.: CBO, March 10. http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/120xx/doc12085/03-10-ReducingTheDeficit.pdf

Fieldhouse, Andrew, and Ethan Pollack. 2011. “Tenth Anniversary of the Bush-Era Tax Cuts: A Decade Later, the Bush Tax Cuts Remain Expensive, Ineffective, and Unfair.” Policy Memorandum No. 184. Washington, D.C.: Economic Policy Institute, June 1. http://www.epi.org/publication/tenth_anniversary_of_the_bush-era_tax_cuts/

Fieldhouse, Andrew, and Isaac Shapiro. 2011. “The Facts Support Raising Revenues From the Highest-Income Households.” Washington, D.C.: Economic Policy Institute, August 5. http://www.epi.org/publication/the_facts_support_raising_revenues_from_the_highest-income_households/

Internal Revenue Service (IRS). 2011. “SOI-Tax Stats-Taxpayers With Top 400 Adjusted Gross Income.” Tax Years 1992-2007. Washington, D.C.: IRS. http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/07intop400.pdf

Jacobson, Darien, Brian Raub, and Barry Johnson. 2011. “The Estate Tax: Ninety Years and Counting.” SOI Tax Stats – Estate Tax SOI Bulletin Articles. Washington, D.C.: Internal Revenue Service. http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/ninetyestate.pdf

Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT). 2009a. “Estimated Effects of the Revenue Provisions of H.R. 3200, The ‘America’s Affordable Health Choices Act of 2009.’” Washington, D.C.: JCT. www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=showdown&id=3570

Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT). 2009b. “Estimated Revenue Effects of the Amendment in the Nature of a Substitute to H.R. 4872, The ‘Reconciliation Act of 2010,’ as Amended, in Combination With the Revenue Effects of H.R. 3590, The ‘Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA),’ as Passed by the Senate, and Scheduled for Consideration by the House Committee on Rules on March 20, 2010.” Washington, D.C.: JCT. http://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=download&id=3672&chk=3672&no_html=1

Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT). 2011a. “Estimated Budget Effects of the Revenue Provisions Contained in the President’s Fiscal Year 2012 Budget Proposal.” Washington, D.C.: JCT, April 18. http://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=3773

Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT). 2011b. “Description of Revenue Provisions Contained in the President’s Fiscal Year 2012 Budget Proposal.” Washington, D.C.: JCT, June 14. http://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=3796

Marr, Chuck, and Jason Levitis. 2009. “Lincoln-Kyl Estate Tax Amendment Is Both Unnecessary and Unaffordable.” Washington, D.C.: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 10. http://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=2759#_ftn1

Office of Senator Bernie Sanders (Sanders). 2010. “Release: Sanders Bill Restores Estate Tax on Billionaires.” Washington, D.C.: United States Senate, Office of Senator Bernie Sanders. http://sanders.senate.gov/newsroom/news/?id=75853b2b-cb95-4c97-8d4c-9ad9c4572756

Office of Management and Budget (OMB). 2011a. “Living Within Our Means and Investing in the Future: The President’s Plan for Economic Growth and Deficit Reduction.” Washington, D.C.: OMB, September 19. http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/budget/fy2012/assets/jointcommitteereport.pdf

Office of Management and Budget (OMB). 2011b. “Mid-Session Review, Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2012.” Washington, D.C.: OMB, September 1. http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/budget/fy2012/assets/12msr.pdf

Office of Management and Budget (OMB). 2011c. “The American Jobs Act: President Obama’s Plan to Create Jobs Now.” Washington, D.C.: OMB, September 12. http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/legislative/reports/american-jobs-act.pdf

Office of Management and Budget (OMB). 2011d. “Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2012, Analytical Perspectives, Federal Receipts.” Washington, D.C.: OMB, February 14. http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/budget/fy2012/assets/receipts.pdf

Our Fiscal Security (OFS). 2010. Investing in America’s Economy: A Budget Blueprint for Economic Recovery and Fiscal Responsibility. Washington, D.C.: Demos, Economic Policy Institute, and The Century Foundation. http://www.epi.org/page/-/EPI_BlueprintPaper_R7.pdf?nocdn=1

Pollin, Robert, Dean Baker, and Marc Schaberg. 2002. “Securities Transaction Taxes for U.S. Financial Markets.” Working Paper No. 20. Amherst, Mass.: Political Economy Research Institute, October. http://www.peri.umass.edu/fileadmin/pdf/working_papers/working_papers_1-50/WP20.pdf

Tax Policy Center (TPC). 2008a. “T08-0150 – Individual Income and Estate Tax Provisions in the 2001-08 Tax Cuts, Distribution of Federal Tax Change by Cash Income Level, 2010.” Washington, D.C.: TPC, The Numbers website, July 2. http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/numbers/displayatab.cfm?Docid=1859&DocTypeID=1

Tax Policy Center (TPC). 2008b. “Tax Capital Gains as Ordinary Income, Distribution of Federal Tax Change by Cash Income Percentile, 2007.” TPC,The Numbers website, January 30. http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/numbers/displayatab.cfm?Docid=1763&DocTypeID=2

Tax Policy Center (TPC). 2011a. “Administration’s FY2012 Budget Proposals; Allow the 2001-2003 Tax Cuts to Expire at the Highest Income Levels; Baseline: Current Policy; Distribution of Federal Tax Change by Cash Income Percentile, 2013.” TPC, The Numbers website, March 18. http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/numbers/displayatab.cfm?DocID=2964

Tax Policy Center (TPC). 2011b. “T11-0338 – President Obama’s American Jobs Act of 2011: All Offsets Baseline: Current Law Distribution of Federal Tax Change by Cash Income Percentile, 2013.” Washington, D.C.: TPC, The Numbers website, September 16. http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/numbers/displayatab.cfm?Docid=3186&DocTypeID=2

Tax Policy Center (TPC). 2011c. “T11-0340 – President Obama’s American Jobs Act of 2011: 28 Percent Limitation on Certain Deductions and Exclusions Baseline: Current Law Distribution of Federal Tax Change by Cash Income Percentile, 2013.” Washington, D.C.: TPC, The Numbers website, September 16. http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/numbers/displayatab.cfm?Docid=3188&DocTypeID=2

Tax Policy Center (TPC). 2011d. “T11-0366 – President Obama’s Proposals for the Joint Committee Baseline: Current Policy Distribution of Federal Tax Change by Cash Income Percentile, 2013.” Washington, D.C.: TPC, The Numbers website, September 21. http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/numbers/displayatab.cfm?Docid=3209&DocTypeID=2

Tax Policy Center (TPC). 2011e. “T11-0365 – President Obama’s Proposals for the Joint Committee Baseline: Current Policy Distribution of Federal Tax Change by Cash Income Level, 2013.” Washington, D.C.: TPC, The Numbers website, September 21. http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/numbers/displayatab.cfm?Docid=3208&DocTypeID=1

Tax Policy Center (TPC). 2011f. “T11-0363 – President Obama’s Proposals for the Joint Committee Baseline: Current Law Distribution of Federal Tax Change by Cash Income Level, 2013.” Washington, D.C.: TPC, The Numbers website, September 21. http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/numbers/displayatab.cfm?Docid=3206&DocTypeID=1

Tax Policy Center. 2011g. “Individual Income Tax Parameters (Including Brackets), 1945-2011.” Washington, D.C.: TPC, Tax Facts website, January 20. http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxfacts/Content/Excel/individual_rates.xls

Tax Policy Center. 2011h. “Historical Top Tax Rate.” Washington, D.C.: TPC, Tax Facts website, January 31. http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxfacts/displayafact.cfm?Docid=213