Though the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) now has GDP growing again, this morning’s Bureau of Labor Statistics’ October employment report found that the jobs situation nevertheless continues to worsen. Unemployment rose dramatically to 10.2% in October, the highest rate since April 1983. With 190,000 payroll jobs lost, October marked the 22nd consecutive month of job loss and the longest streak in 70 years.

The upside is that October’s loss of payroll jobs is smaller than earlier in the year, and much smaller than the average monthly loss of nearly 700,000 jobs each month in the first quarter of 2009. From the second quarter of 2009 onward, the ARRA has created or saved between 170,000 to 235,000 jobs per month; losses in October would likely have been around 400,000 without it.

Since the start of the recession in December 2007, an estimated 8.1 million jobs have been lost. This number includes both the 7.3 million jobs lost in the payroll data as currently published, plus the preliminary annual benchmark revision released on October 2nd, which showed an additional 824,000 jobs lost from April 2008 to March 2009. And even this number understates the magnitude of the hole in the labor market by failing to take into account the fact that the population is always growing. To keep up with population growth, the economy needs to add approximately 127,000 jobs every month, which translates into 2.8 million jobs over the 22 months since the start of the recession. This means the labor market is currently 10.9 million jobs below what is needed to return to the pre-recession unemployment rate. In order to fully fill in the gap in the labor market by October 2011, employment would have to increase by an average of 582,000 jobs every month between now and then, a sustained rate not seen since 1950-51.

The labor force now has 903,000 fewer workers than it did a year ago, which is remarkable given that the working-age population grew by 0.8% over this period. If these missing workers were counted as part of the labor force, the unemployment rate would have been 10.7% in October. Over the last year, the labor force participation rate of people age 16-24 has dropped by 2.9 percentage points, from 58.4% to 55.5%, while the labor force participation rate of people age 25-54 has dropped by 0.5 percentage points, from 83.1% to 82.6%. People age 55 and over, however, have increased their labor force participation, from 39.8% to 39.9%, over the last year. This increased labor force participation among older workers (especially women) is likely due to a decline in retirement security, as the collapse of the housing bubble and the plunge in stock prices have hit older people more than other groups.

Although layoffs are moderating significantly, hiring is not yet picking up, and that means unemployed workers are not able to find jobs. This recession continues to shatter all post-Great-Depression records for length of unemployment spells. In October, an additional 156,000 jobless workers crossed the six-months threshold. Of the 15.7 million unemployed workers in this country, 5.6 million (35.6%) have been jobless for over six months. This is 3.6% of the total labor force — far surpassing the previous peak of 2.6% set in June 1983. Currently, the average unemployment spell is over six months (26.9 weeks), the longest on record.

Furthermore, the official unemployment count understates slack in the labor market by excluding both the jobless who want work but have given up looking (“marginally attached” workers) and people who are working but can’t get the full-time hours they want (“involuntary part-time” workers). In October, there were 2.4 million marginally attached workers, 9.3 million involuntary part timers, and 15.7 million unemployed workers in the United States, for a total of 27.4 million workers who are either unemployed or underemployed. This represents 17.5% of U.S. workers.

Demographic breakdowns in unemployment show that, while all major groups have experienced substantial increases, young workers, racial and ethnic minorities, men, and workers with lower levels of schooling are getting hit particularly hard.

- In October, unemployment was 19.1% among workers age 16-24, 9.2% among workers age 25-54, and 7% among workers age 55+ (increases of 7.5, 5.2, and 3.9 percentage points, respectively, since the start of the recession).

- Unemployment was 15.7% among black workers, 13.1% among Hispanic workers, and 9.5% among white workers (increases of 6.8, 6.9, and 5.1 percentage points, respectively, since the start of the recession).

- Unemployment was 11.4% for men, compared to 8.8% for women (increases of 6.4 and 4 percentage points since the start of the recession).

- For workers age 25 or older, unemployment reached 11.2% for high school educated workers and 4.7% for those with a college degree (increases of 6.6 and 2.6 percentage points, respectively, since the start of the recession).

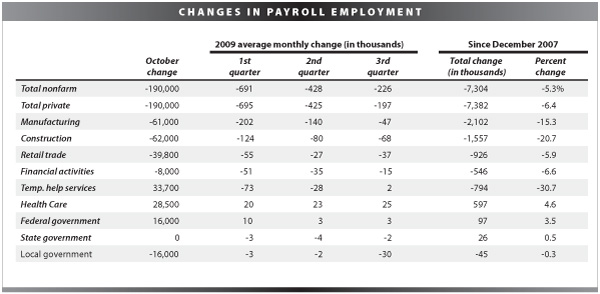

On a more positive note, job losses are moderating in most industries. The table below shows October losses compared to average monthly losses in each of the last three quarters for select industries. Construction has lost 20.7% of employment since the start of the recession in December 2007, but the October loss of 62,000 was smaller than the losses in any of the previous three quarters. Manufacturing has lost 15.3% of employment since the start of the recession; the October loss of 61,000 manufacturing jobs was smaller than the losses in the first two quarters, though larger than in the 3rd quarter.

Temporary help services added 33,700 jobs, the largest gain in that sector in two years. The growth in temporary help services is very good news, as this sector tends to lead broader recoveries. Health care also continued to gain jobs, adding 28,500 in October.

The federal government added 16,000 jobs, while state governments remained flat and local governments lost 16,000 jobs. Unlike in the private sector, the government employment situation has not been improving over the year, as state and local budget problems due to the recession have forced these governments to make job cuts.

Growth in the nominal hourly wages of production workers dropped from 3.9% during the first year of the recession (December 2007-December 2008) to a 2.4% growth rate over the last year. Nominal average weekly earnings grew 2.4% for the first year of the recession, but fell to a 0.9% growth rate over the last year. This collapse in wage growth will slow the recovery by reducing consumption. Furthermore, the average workweek remained flat in October, at 33 hours, which is also not good news, since hours are expected to pick up before employment does, as employers increase the hours of the workers they have before hiring new employees.

The October employment report shows that, despite the big jump in unemployment, the rate of job loss continues to moderate. The ARRA has stopped the freefall, but the scale of economic decline is so large that the ARRA has not been enough to prevent rising unemployment. Today’s unemployment numbers are a wake-up call. Unless Congress authorizes substantial additional spending for job creation, unemployment will remain elevated for years to come.

Research assistance from Kat

hryn Edwards and Andrew Green.