Prepared testimony by David Cooper, Economic Analyst, Economic Policy Institute, to the Montgomery County Council

To: Montgomery County Council

From: David Cooper, Economic Analyst, Economic Policy Institute

Date: Tuesday, November 26, 2013

Re: In support of Bill 27-13, Human Rights and Civil Liberties – County Minimum Wage

Thank you for holding a hearing on raising the county’s minimum wage. I want to briefly provide some context for a minimum wage of $11.50, discuss the population likely to be affected, and describe briefly how we might expect any increase to affect the regional economy. I also want to note the importance of indexing the minimum wage for inflation and raising the minimum wage for tipped workers.

Putting an $11.50 minimum wage in context

The first thing to remember in considering an $11.50 minimum wage is that over the 3-year phase-in period as the minimum is raised, inflation will be eating away at the new minimum’s real value. Based upon the Congressional Budget Office’s projections for inflation over the next 3 years, a minimum wage of $11.50 in 2016 would equal roughly $10.83 in today’s dollars. This would be slightly higher than the value of the federal minimum wage at its high point in 1968, when it equaled just less than $10 in today’s dollars. However, this was the minimum applicable to the nation as a whole, and thus did not reflect higher costs of living in any particular region.

There is no question that a wage of $7.25 per hour provides far too low an income for someone to live on, particularly in the Washington, DC metropolitan area. A minimum wage worker, working full time, year-round has an annual income of roughly $15,000. As shown in Figure 1A, this is below the federal poverty line for any worker with at least one child.

The figure shows the annual income for minimum wage workers at every value of the federal minimum wage since 1964, adjusted for inflation into constant 2013 dollars. It also depicts the projected value of a minimum wage income under the county’s proposal to raise the minimum wage to $11.50 by 2016. As shown by the dotted line, the county’s proposal would elevate a minimum wage income above the federal poverty line for a family of three, but still below the poverty line for a family of four.

Still, researchers and policymakers readily acknowledge that the federal poverty line is not the best measure of actual living standards, in large part because it does not reflect differences in regional cost-of-living. EPI produces a tool called the Family Budget Calculator, which estimates the true annual income required for families of varying sizes to have a modest, but adequate standard of living in any particular region of the country. Comparing the Family Budget Calculator’s estimate for the Washington, DC metropolitan area to the median Family Budget estimate for the United States (Topeka, KS), the DC metro area’s expenses are roughly 40 percent greater than the median. Figure 1B shows the real value of a minimum wage income relative to an “adjusted” poverty line that is 40 percent higher than the official federal poverty line.

As the figure shows, if you adjust the federal poverty line to reflect the region’s higher cost-of-living, the county’s proposed $11.50 minimum wage would provide an income just above the adjusted poverty line for a family of two.

It’s also important to note that over the past 40 years, Maryland’s workers have become far more productive, yet their pay has not kept pace with their ability to generate more from an hour’s worth of work. From 1979 through 2012, output per worker expanded 74 percent for workers in Maryland, yet median real compensation grew only 18 percent. For low-wage workers, it was even worse: over that same time period workers in the bottom fifth of the wage distribution in Maryland saw their wages increase only 3.2 percent.

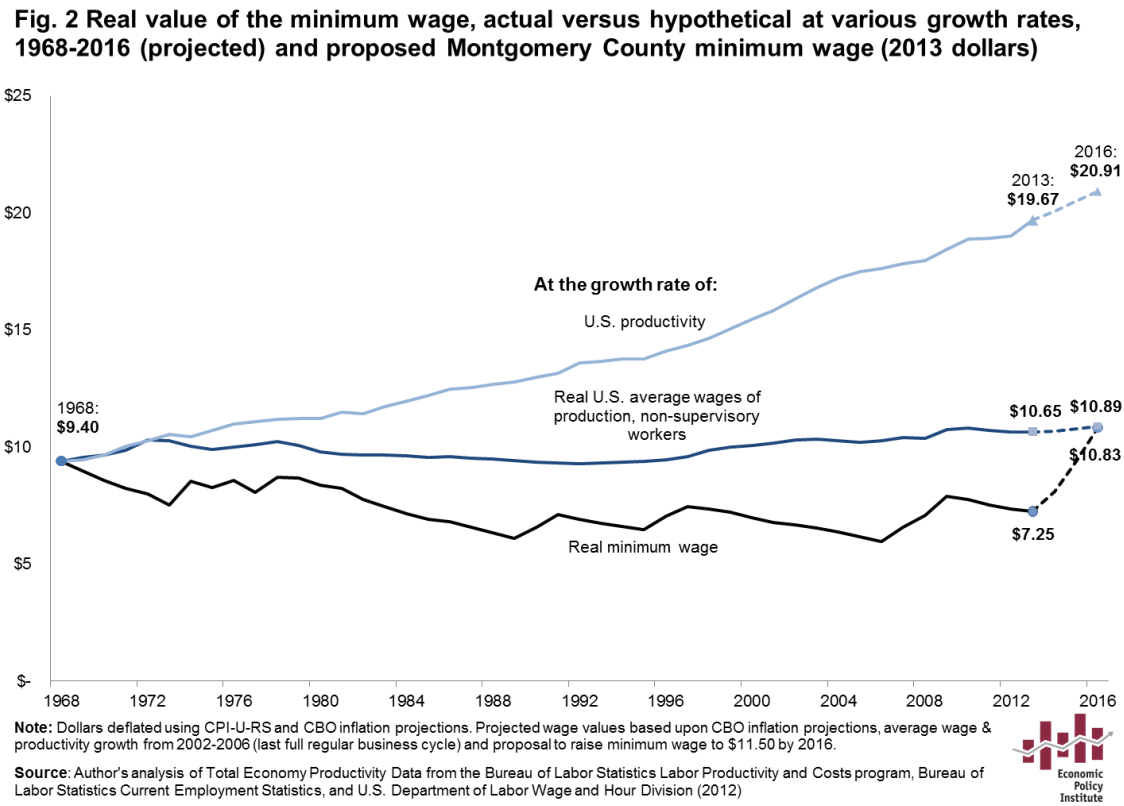

Figure 2 shows the real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) value of the minimum wage at its high point in 1968, and what the minimum wage would be today if it had grown since then at the same rate as average wages for production, non-supervisory workers or overall U.S. productivity.1

If the minimum wage had grown at the same rate as growth in wages for the average American worker, it would be $10.65 today and about $10.89 by 2016. If the minimum wage had grown with productivity since the late 1960s, it would be $19.67 today, and just under $21 per hour under reasonable expectations for productivity growth. This means that our economy has the capacity for a minimum wage far higher than $11.50; we have simply chosen to let its real value erode and not given the lowest paid workers any of the benefits of improvements in our ability to generate income.

Who would be affected by raising the county minimum wage to $11.50 per hour?

It is difficult to estimate the exact number of workers who would be affected by a county minimum wage increase from existing public data sources because most public surveys on wages do not have sufficient sample sizes for analyses at the county level. However, using data from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, EPI was able to estimate that there are roughly 80,000 people who work in Montgomery County currently earning less than $12 per hour. It is likely that some of these workers will not be affected by the increased minimum wage; however, some workers earning just above $11.50 and even above $12 per hour will also likely receive a small pay increase as employers adjust their overall pay ladders.

Contrary to common perceptions of low-wage workers, the vast majority are not teenagers. We estimate that only about 10 percent of the workers earning less than $12 per hour in Montgomery County are teens. About 44 percent are between the ages of 20 and 34; 33 percent are between 35 and 44; and 13 percent are age 55 or older.

Of the workers earning less than $12 per hour in Montgomery County, 55 percent are women. The majority of these workers has at least some college education, and just less than one third (31.8 percent) has children. About 17 percent of these workers work full-time, although about 60 percent work at least 20 hours per week.

What does the economics literature say about increasing the minimum wage? Does increasing the minimum wage lead to job losses?

The earliest research in the 1960 and 70s found results consistent with the basic supply-and-demand understanding of competitive labor markets, which holds that an increase in the minimum wage above a market-determined wage rate, the “market-clearing rate”, will lead to a loss of jobs. Some studies also suggested that increases in the minimum wage led to offsetting reductions in hours, so that minimum wage workers did not actually see their incomes improve. Thus, at that time, there was a general consensus among economists that increases in the minimum wage would cause job loss and may be bad for its intended beneficiaries.

In the 1990s, this consensus began to unravel. A new round of research showed that increases in the minimum wage caused no employment losses and some studies actually showed employment gains. The most famous of these studies, by David Card and Alan Krueger, examined fast food employment in border counties between New Jersey and Pennsylvania when New Jersey raised their minimum wage but Pennsylvania did not.2 Card and Krueger’s results showed that employment rose in New Jersey, where the minimum wage had gone up, while employment in Pennsylvania declined.

There were other studies that still showed employment declines, most notably by David Neumark and William Wascher.3 Neumark and Wascher utilized national-level data, and the fact that different states have increased their state-level minimum wages at different times, to isolate the independent effect of increasing the minimum wage. They found statistically significant negative employment effects from increases in the minimum wage, although the effects they found were considerably smaller than those found in earlier research.

By the mid-2000s, this is where the literature stood, with national-level approaches finding small negative effects on employment from increasing the minimum wage, and case study approaches like Card and Krueger’s paper, finding no such disemployment effects, and sometimes small, positive employment effects.

In the last few years, the missing link between these two different methodologies was bridged. A new round of research, utilizing both national-level and case-study approaches, showed that increases in the minimum wage had no negative effect on employment. One of these studies, by Arin Dube, William Lester, and Michael Reich utilized the case study method of looking at border regions between states with differing minimum wages, but applied it at the national level.4 They compared employment in every single pair of neighboring U.S. counties that straddle a state border and had differing minimum wage levels at any time between 1990 and 2006. This allowed them to analyze employment and earnings data for over 500 counties. They found that minimum wage increases did not cause job losses. At the same time, their research showed that minimum wage increases did clearly lead to increased earnings for low-wage workers.

How will raising the minimum wage affect the area economy?

As I mentioned before, increases in the minimum wage have been shown to result in significant increases in earnings for households with low-wage workers. This finding was confirmed by another recent study by economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.5 They analyzed 23 years of household spending data and found that an increase in the minimum wage causes households with a minimum wage worker to measurably increase their spending over the next year.

This is a critical point because it describes how raising the minimum wage can have positive regional effects. The minimum wage goes primarily to workers in low and moderate-income families who depend on their earnings to get by. These are the families with little choice but to spend every additional dollar they earn. Economists would say that they have a high “propensity to consume out of income”. Thus when you raise the minimum wage, you put more money in the hands of those most likely to spend it right away. Low-wage workers are far more likely to spend additional income than corporations, business owners, or shareholders – and more likely to spend that income locally.

At the same time, it is not entirely clear that businesses would lose all that income. For example, we know that businesses see some offsetting gains when the minimum wage is raised, particularly from reductions in turnover costs, improvements in organizational efficiency, and small price increases.

Raising the minimum wage can therefore benefit the regional economy because it shifts income from an entity less likely to spend it or spend it locally—the employer—to one that is very likely to spend it and to do so in area businesses—the low-wage worker.

The importance of indexing

As I mentioned at the beginning of my testimony, every year that the minimum wage remains the same in nominal terms, inflation eats away at that wage’s purchasing power. Minimum wage workers have to either cut back on their spending or find ways to supplement their income simply to afford the same level of spending they had the previous year. This threaten the well-being of minimum wage workers, it weakens the consumer demand that drives U.S. GDP, and it strains public budgets as more and more low-wage workers have to turn to public assistance programs in order to supplement their inadequate wages. Indexing prevents this from happening by ensuring that a minimum wage paycheck maintains a constant purchasing power.

Moreover, indexing the minimum wage can actually provide greater stability for low-wage employers who can then anticipate their increased year-over-year wage costs and plan to accommodate a small increase, rather than having to question when a minimum wage hike might occur and then absorb a large increase because lawmakers recognize that the minimum has stagnated for too long.

There are currently 11 states that have some form of minimum wage indexing.6 While there is no county-level precedent for indexing, there is no reason to expect that the effects of having an indexed county-level minimum wage would be any different than what takes place along state borders where one state has indexing and the other does not.

The tipped minimum wage

Finally, I want to note the importance of raising the tipped minimum wage. A 2011 EPI and UC-Berkeley study showed that the poverty rate among tipped workers nationwide was 14.5 percent, more than double the 6.3 percent poverty rate of all workers.7 However, the disparity in poverty rates between tipped and non-tipped workers was noticeably smaller in states with no tipped minimum wage. There are seven states with no tipped minimum wage8 – workers in these states are paid the same wage as non-tipped workers. In these states, the poverty rate of tipped workers was 12.1 percent, compared to an overall poverty rate of 6.7 percent. In the 18 states with a tipped minimum wage of $2.13, the poverty rate for tipped workers was 16.1 percent, despite the fact that they had the same 6.7 percent overall poverty rate as the states with no tipped minimum wage.

This correlation between lower tipped minimum wages and higher poverty rates among tipped workers suggests that having significantly different wage floors for tipped versus non-tipped employees results in noticeably different living standards for these two groups. Forcing service workers to rely on tips for their wages creates tremendous instability in income flows, making it more difficult to budget or absorb financial shocks. The restaurant industry is essentially the only industry in America where the consumer must pay a portion of the business’ wage obligation. There is no economic justification for having a tipped minimum wage significantly lower than the regular statutory minimum wage; it is purely an artifact of political horse-trading.

I understand that the county is pursuing this increase in conjunction with other regional jurisdictions, and that the Maryland state legislature may also be considering increasing the state’s minimum wage. I would encourage the council to not be timid in pursuing its own increase. A higher regional minimum wage or a state increase would certainly benefit a larger number of people. Yet the experience of San Francisco is instructive: cities can pass higher minimum wages without hampering business or employment growth, and as was the case in California, this can provide crucial evidence that eventually motivates a broader state-level increase.

For these reasons I encourage the Council to pass Bill 27-13.

Endnotes

1. Production, non-supervisory workers comprise about 80 percent of all U.S. workers.

2. Card, David, and Alan B. Krueger. Minimum wages and employment: A case study of the fast food industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. No. w4509. National Bureau of Economic Research, 1993.

3. Neumark, David, and William L. Wascher. Minimum wages. MIT Press, 2008.

4. Dube, Arindrajit, T. William Lester, and Michael Reich. “Minimum wage effects across state borders: Estimates using contiguous counties.” The review of economics and statistics 92.4 (2010): 945-964.

5. Aaronson, Daniel, Sumit Agarwal, and Eric French. “The Spending and Debt Response to Minimum Wage Hikes.” (2008).

6. The 11 states with indexing are: Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, Ohio, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington.

7. Allegretto, Sylvia and Kai Fillion. “Waiting for Change: The $2.13 Subminimum Wage”. Economic Policy Institute, 2011.

8. The seven states with no tipped minimum wage are: Alaska, California, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington.