Policy Memo #154

EPI Policy Memorandum #154

On October 13th, the Senate Finance Committee approved a health reform bill, making it the fifth Congressional committee to pass health care reform legislation. Before the House and Senate can agree on a final bill, Senate leaders must first reconcile the new Finance bill with one that the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pension (HELP) committee drafted over the summer. While there is substantial overlap between these two bills, the HELP reform bill is superior on most fronts.

Both proposals would end many of the most egregious practices of private insurance companies, such as denying coverage for pre-existing conditions or dropping policyholders when they get sick. Both proposals also call for the creation of health insurance exchanges, or new regulated marketplaces where insurers would compete to provide affordable coverage to individuals and small businesses. In the exchange, insurers would be required to comply with minimum standards of coverage and transparency so enrollees could easily compare plans against one another. Both bills also require some degree of shared responsibility between individuals, employers, and the government.

But the devil is in the details and those details reveal the HELP legislation to be as good or superior to the Finance bill on all the following issues:

– affordability of adequate insurance

– strong and broad insurance exchanges

– a robust public option

– a fair and equitable employer mandate

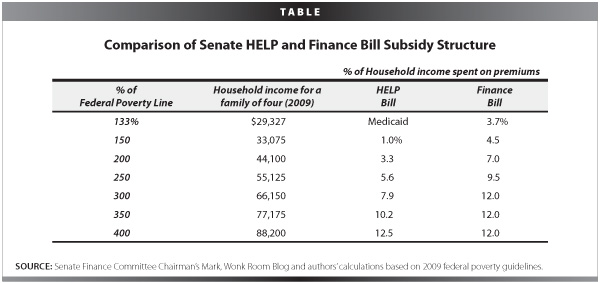

Affordability of adequate insurance: The Senate HELP bill scores good marks on the goal of guaranteeing affordability for most Americans by providing generous subsidies for households with incomes of up to four times the poverty line ($88,200 a year for a family of four). The Senate Finance bill provides less generous subsidies for most households, and is especially stingy with subsidies for low- and middle-income households that are most vulnerable to income stress stemming from high health insurance premiums. Under the HELP bill, a household with income twice the poverty line ($44,100 for a family of four) would pay no more than 3.3% of their income toward premiums. Under the Finance bill, that same family would pay more than twice that: as much as 7% of its total income. In dollar amounts, that family could pay $1,632 a year more in premiums under the Senate Finance bill.

Table 1 below presents a more detailed comparison of the share of income that different households would have to pay under the two different proposals. At nearly all levels, the Finance committee bill would require a much greater share of income to be spent on premiums compared to the HELP bill.

Furthermore, the amount that low- and middle-income households would be required to pay in premiums under the Finance proposal would actually increase over time, since the legislation shifts from measuring premiums as a share of income in the first year, to measuring them as a share of the total premiums in subsequent years. Since health insurance premiums have historically grown faster than income, under the Finance bill, household premiums would grow each year with the growth of insurance premiums.

The legislation that the Senate finally agrees on should ensure that insurance is affordable for all families, particularly low- and middle-income households, and also ensure that subsidies are measured against household income rather than against health insurance premiums, so that the subsidies do not become grossly insufficient over time.

The Finance panel proposal also contains a provision that could automatically cut the level of subsidies. If the Director of the Office of Management and Budget determines that the Finance bill produces a net budget deficit in a given year, the federal government would be required to reduce the subsidies by the amount required to achieve budget neutrality. Based on Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates of Senate Finance legislation, mandating budget neutrality could result in automatic subsidy cuts of an average of 15% between 2015 and 2018. While failsafe provisions are an important way to achieve cost control, they should not run against the goal of reform: to make coverage more, not less affordable. Prior research has highlighted better places for the federal government to enact automatic failsafe provisions to ensure the deficit neutrality of health reform in the future.

Both Senate bills would cap out-of-pocket spending on medical expenses such as deductibles and co-payments at $5,950 for individuals and $11,900 for families. Annual out-of-pocket expenses at these levels could be devastating for many middle-income households. Median income for a family of four in 2008 was $50,303; under the Senate bills, a family earning that could spend up to 24% of its annual income on health care premiums and out-of-pocket expenses. The minimum standards for insurance packages should be improved in the final Senate bill to ensure that households are protected from high catastrophic medical expenses.

Strong and Broad Insurance Exchanges: The effectiveness of any health reform law will depend largely on the strength of newly created health insurance exchanges. Basic economics dictates that the larger these insurance marketplaces are, the better they will work. Broader insurance pools lower premiums and administrative costs, and encourage better negotiation between insurers and medical providers. It is important to remember here that the two Senate bills are not the only reform legislation in Congress. The three committees with jurisdiction over the health care system in the House—Energy and Commerce, Ways and Means, and Education and Labor—have already produced legislation that provides a much stronger model on nearly all counts when compared to either the HELP or Finance proposals. The House legislation, which proposes the formation of a national insurance exchange, is far superior to both the Senate HELP and Finance bills, which propose state or regional exchanges open only to uninsured individuals and small firms.

Health insurance exchanges should be open to all individuals and employers of all sizes, guaranteeing real choice and increasing the size and efficiency of the new marketplace. This would introduce much stronger competition for insurers and would push premium prices down, helping ensure that all individuals and workers have access to affordable coverage.

Another key component of the health insurance exchanges is the ability to negotiate directly with insurers to help guarantee that enrollees get the best rates and that insurers meet certain requirements for quality and customer service. This “prudent purchaser provision” has been an important component in Massachusetts’ state-level health insurance marketplace: Jon Kingsdale, the exchange’s director, says that health insurance exchanges that don’t have a “prudent purchaser provision” would be a “policy disaster.” This provision is included in the HELP bill, but not the Finance panel legislation. Health care legislation should empower the exchange to negotiate the best rates for its enrollees and enforce strong quality standards.

A Robust Public Option: As has been highlighted in extensive prior research,

a robust national public insurance plan should be a choice within the new exchange. It is a key method of holding private insurers accountable and ensuring a minimum standard of efficiency. A public option also remains overwhelmingly popular amongst the American public.

Although the HELP reform bill contains a public option, the CBO says that plan would not have a significant impact on premiums or broader cost control: The plan HELP proposes would have to establish its own network of providers from scratch and would tend to attract less healthy individuals. The insurance co-operatives, as included in the Finance bill, would be even less effective. The CBO concluded that the co-ops, as currently structured in the Finance bill, would have very low enrollment. A public plan, in order to be effective, must have strong infrastructure in place when it launches, that allows it to build provider networks and markets across the country. The House bill links the public plan to Medicare initially, which would help it quickly establish a national presence and effectively compete against existing insurers. Final Senate legislation should include a strong and robust public plan in the menu of choices for consumers in the exchange.

A Fair and Equitable Employer Mandate: The employer mandate is another key component of successful reform. Currently, employers who offer good coverage to their workers are at a disadvantage if their competitors shirk their responsibility. The best way of correcting this is to set required contributions as a share of a firm’s payroll. Fixed-dollar contributions, as specified in the Senate HELP bill, are generally too low to raise money for insurance subsidies.

The Finance Committee bill contains a “free-rider” provision that would have particularly detrimental effects, generating only a low level of contributions and, worse, encouraging discrimination against low-income and minority workers. The free-rider mandate would require firms with more than 50 employees to pay a large fixed-dollar amount of $4,000 or more for each uninsured worker who qualifies for premium subsidies in the insurance exchange or is eligible for Medicaid. No contribution would be required on behalf of workers who do not qualify for subsidies. That would give employers a large incentive to avoid hiring low- and middle-income workers, effectively discriminating against individuals they believe to be eligible for subsidies.

Although neither the HELP nor Finance employer mandates are ideal when compared to the House proposal, which includes a share-of-payroll tax on employers who don’t offer health insurance (with a generous exemption for small businesses), the HELP committee’s fixed dollar amount is far better than the free-rider provision in the Finance committee, which could have detrimental effects on the labor market.

Both the Finance and HELP committee bills represent important steps towards health reform, but it would be a mistake to view the two interchangeably. Senate leadership must pay careful attention to key differences when merging the two bills together. These details can make the difference in achieving meaningful and affordable universal coverage.