A tax on high-priced health plans has been one of the options proposed for paying for health care reform. The Senate Finance Committee has proposed an excise tax of 40% on the more expensive plans and that proposal has a good chance of making it into the final Senate health reform legislation since the other Senate committee that has drafted a reform bill, the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) does not have jurisdiction over financing. But far from a tax on a small number of very-high-quality, high-cost health plans, this proposed tax on so-called Cadillac health plans could actually affect one-third of all health plans in the near future. This week, as Senate leadership works to merge health reform bills from the Finance and the HELP committees, they need to keep in mind that this proposed excise tax would affect not just the Cadillacs of health insurance but a lot of ordinary plans as well.

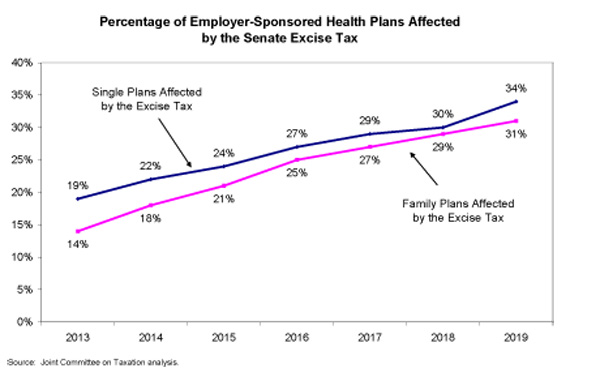

The Senate Finance bill, America’s Healthy Future Act, proposes an excise tax of 40% on employer-sponsored health insurance premiums which exceed $8,000 for single plans and $21,000 for family plans in 2013. Previous research has shown that high-priced plans are not always high-value or high-quality plans. Furthermore, the Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that about one-third of all health plans would be affected by this excise tax by 2019. This would seem to suggest that either one-third of all plans are actually so-called Cadillac plans, or, more likely, the excise tax will hit a lot more ordinary plans than suggested.

The key is in the indexing. While the excise tax would initially apply to plans costing more than $8,000 a year for individuals and $21,000 for families, these cut-off values are indexed to the growth in overall inflation plus one percent, or more specifically consumer price index plus one (CPI+1). But medical costs and health insurance premiums rise at a much faster pace. In fact, over the 2000s, premiums rose three to four times faster than the CPI. Indexing the excise tax cut-offs to this slower rate of growth means that an increasing number of plans in future years will be affected by this tax. That said, the tax would have a wide reach even in its first year, applying to 19% of individual plans and 14% of family plans.

Revenue from the excise tax would come from two main sources. Some would be garnered directly from taxes on those higher-cost plans. The second source of revenue would be indirect. It is based on the assumption that when workers choose less expensive health plans, as many will do to avoid the tax, they will see those health dollars translated into increased wages, and the federal government will see increased income and payroll taxes on these additional wages. While in the short run it seems unlikely that workers will recoup lower benefits in the form of higher wages, it is clear that they will wind up with lower quality benefits.

To the extent that workers choose less expensive health plans for themselves and their families to avoid the excise tax, they will be faced with higher out-of-pocket costs. All else equal, lower premiums translate into less comprehensive coverage. Less comprehensive coverage often takes the form of higher deductibles, increased co-pays, higher out-of-pocket maximums, or other increased cost-sharing.

This erosion of plan quality would be an unwelcome change for those with high and growing out-of-pocket burdens, especially when it is done in the name of reform. Out-of-pocket costs have already increased significantly this decade, a trend that is particularly burdensome for people who are sick or have modest incomes. More than half of all bankruptcies are associated with high medical expenses, and three-quarters of those bankruptcies were filed by people who actually had health insurance. These problems will only be exacerbated by less comprehensive coverage caused by the excise tax. The burden will weigh especially heavily on those in the most need of medical care because of chronic conditions or other ongoing expensive illnesses. When the poor and sick delay medical care because of the high cost, they often become sicker, which costs the health care system more money in the long run.

The proposed excise tax would hit far more health plans than advertised. It cannot be argued with any reliability that the tax will only affect very high cost health plans unless we assume that one-third of people who have health insurance have gold-plated plans. Furthermore, health plans are expensive for many reasons other than simply that they provide more comprehensive coverage. For instance, small businesses are paying high premiums for the insurance they provide to their employees not because the plans are especially lavish, but because they have high administrative costs and include too few employees to constitute the broader risk pool that would qualify them for lower premiums.

While the excise tax would free up enormous sums of money to defray the costs of fundamental health reform, taxing benefits should not be considered until large-scale health reform is in place to cover everyone. Without affordability subsidies and a strong national insurance exchange up and running, a policy of taxing health benefits over a certain dollar amount would serve as a blunt instrument that may do great harm to the very people we should be striving to help.