For today’s unemployed workers, job searches often last six months or longer. The Great Recession and the slow recovery that has followed have been marked not only by persistently high rates of unemployment but also unusually long periods of unemployment. In the third quarter of 2010, 43% of the unemployed had been looking for work for more than six months, and 22.7% had been looking for work for more than a year.

Many of these unemployed workers are in their teens or twenties. Others are nearing retirement age. They are young and old, black, white, Hispanic, Asian American, and Native American. Some lack high  school degrees, others have advanced degrees. Despite their demographic differences, they are united by the simple bad luck of having lost their jobs during the worst recession since the Great Depression, which thrust them into a job market where the odds were stacked solidly against them. Two million long-term unemployed – those who have been seeking work for six months or longer – will lose their unemployment insurance benefits before the end of this year if Congress fails to act to maintain extended benefits.

school degrees, others have advanced degrees. Despite their demographic differences, they are united by the simple bad luck of having lost their jobs during the worst recession since the Great Depression, which thrust them into a job market where the odds were stacked solidly against them. Two million long-term unemployed – those who have been seeking work for six months or longer – will lose their unemployment insurance benefits before the end of this year if Congress fails to act to maintain extended benefits.

Annette Tomberg, 50, of Sacramento, California (pictured) is one of them. In August of 2009, she was laid off from her job at a book binder, where she had worked for three years operating a paper cutter, shrink-wrapping books, and lifting heavy boxes. In the 15 months since, she has applied for multiple jobs every day, rarely receiving even an acknowledgment of her application. Her life, when not consumed by scouring online job boards and taking online training courses to augment her administrative skills, is spent gingerly going over the family finances and deciding which bills she will pay and which ones she will put off paying. The $295 weekly unemployment insurance she receives helps, but still leaves her $400 short each month. “Either I pay the rent or I pay other bills,” she explains. In order to avoid falling further behind on some bills, she has cashed out her retirement savings. Although her husband still has a job in the printing business, he cannot afford his company’s health insurance. The couple visits drugstore mini-clinics when they are sick, but live in fear of a serious illness. Even with the support of unemployment insurance, the couple is living close to the edge. “If I wasn’t getting those benefits, it would be an even worse situation,” says Tomberg.

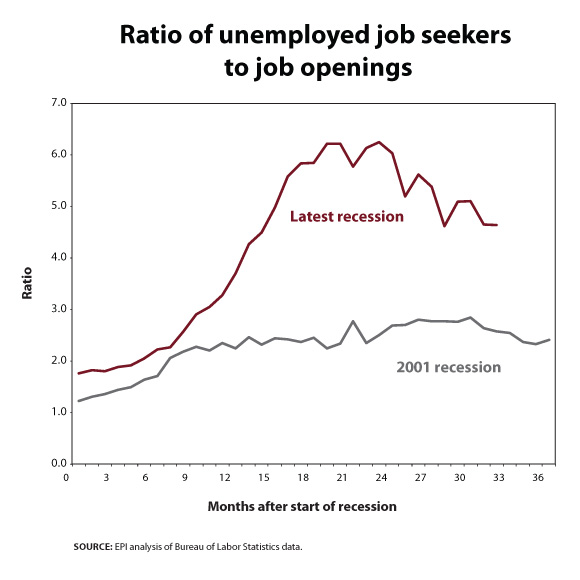

Tomberg’s inability to find work reflects not a lack of skills or initiative, but rather a severe shortage of jobs. In the three years since the Great Recession began, there have at times been more than six unemployed workers competing for every job opening. Today, well over a year since the recession officially ended, there remain five unemployed workers for every job opening. That current ratio is well above the peak of 2.8-to-1 reached in the prior recession and speaks to the difficult odds even the most motivated unemployed worker faces in finding a new job today.

Earlier this year, Rutgers University conducted a nationwide survey of 900 workers who, like Annette Tomberg, were unemployed in August of 2009. It found that six months later, only 21% of them had found full time work, while 67% were still looking and 12% had left the labor force. In other words, eight out of ten of those surveyed who had lost their jobs during the Great Recession were still out of work. Those who found jobs often took a long time to do so. Among those surveyed, 55% of the newly reemployed said their job search had taken more than seven months.

What happens when unemployment drags on for so long? Workers who have struggled for months to find a job often describe a similar cycle of exhausting what savings they had, before being forced to choose between basic essentials: paying the utility bill or buying groceries, paying the rent or going to the doctor. Beyond these daily choices, there are larger tradeoffs: Whether to pay for health insurance or housing, whether to go into more debt today, or preserve college or retirement savings for tomorrow. The Rutgers University survey, No End in Sight: The Agony of Prolonged Unemployment, found that 30% of the unemployed have used food stamps, 18% have visited a soup kitchen, and 70% have used money from savings to make ends meet. Often, those were savings intended for retirement. A January 2010 AARP survey of Americans age 45 and older found that 18% had prematurely withdrawn funds from a 401(K), IRA, or other retirement plan.

Critics of extended unemployment insurance often maintain that giving money to people who cannot find work removes the incentive to look for work. The actual people who are trying to make ends meet on unemployment benefits tell a different story: one of desperately seeking work while fearing their unemployment benefits will be cut off before they find another job. Tim Zaneste, 44, of Flushing, Michigan, has been applying for jobs daily since he was laid off from a software company in June 2009. The unemployment benefits he receives cover only a fraction of his former salary. Like so many unemployed, Zaneste had to withdraw retirement savings, but he still struggled to cover all of his family’s expenses and eventually had to file for bankruptcy protection. Because of the terms of that personal bankruptcy filing, he says he is at risk of losing his modest 1,600 square foot house within 30 days of missing a mortgage payment. Today, his family is a few unemployment checks away from being homeless. “I have worked all my life since the time I was 12,” he says. “Never in my life did I think I would be in this position.”

Zaneste’s family has sold one of their two cars, delayed purchasing new clothing for their children, and even cut back sharply on groceries. This sort of sharp curtailment illustrates how the lost spending power resulting from joblessness impairs the larger economy, and how unemployment insurance can mitigate that effect. EPI President Lawrence Mishel and Economist Heidi Shierholz recently calculated the fiscal benefits of extending unemployment insurance and found that, in addition to saving millions of people from poverty, it would generate more than 700,000 full-time equivalent jobs.

Those findings are consistent with a Congressional Budget Office analysis earlier this year, which found that providing unemployment insurance is the most effective way to stimulate the economy. In May, EPI hosted a panel of economists who explained that these unemployment benefits help people maintain some level of consumption, which in turns stimulates local economies, preventing the loss of some jobs and creating others. “If you give money to someone who is unemployed and has been unemployed for a year, they are going to spend it the next day,” Jesse Rothstein, Chief Economist at the U.S. Department of Labor, said. Another indication of the fiscal value of unemployment insurance came from Harvard Economics Professor Raj Chetty, who also spoke at the conference, where he presented a chart showing a sharp drop in food consumption when a person loses his or her job: the median unemployed person has less than $250 in accessible savings at the time of job loss. This helps explain why unemployment insurance dollars are quickly put back into local communities.

Congress has in the past responded to the severe jobs crisis with multiple extensions to the standard 26 weeks of unemployment insurance, but each extension has been short-lived and unless they are maintained, unemployed workers who have been receiving benefits even a few days beyond six months could be cut off. Brian Sugalski, 39, lost his job as a printing plant manager in May of this year and says that he will miss the cutoff for qualify

ing for extended benefits by four days, unless Congress votes to maintain the extension. Sugalski went from earning an annual salary of $98,000 to receiving $600 a week in unemployment insurance benefits. Because a large chunk of that money goes toward his $800 a month bill for COBRA health insurance benefits and for therapy for his four-year-old disabled son, Sugalski fell behind on other bills. He recently lost his New Jersey home to foreclosure and his family moved in with his wife’s mother in upstate New York, where they continue to seek work. Combining households in such a way has become more and more common. Recent Census Bureau estimates showed the number of adults age 35 and older who are moving in with parents, in-laws, siblings, or other families has reached historically high levels.

Unemployed workers often report higher levels of stress, but some research suggests that the long-term health consequences that result from a job loss are far more significant than is commonly understood. During EPI’s recent event exploring how losing a job jeopardizes your health and can shorten your life, several researchers presented data connecting job loss with poor health, such as weakened immune function and metabolism, stroke, hypertension and heart disease, and even increased mortality rates, which often lasted for years, or decades even after a new job had been found.

While the best way to avoid such outcomes would be to avoid unemployment, the researchers said that given the reality of unemployment there would be great value in making the loss of a job a less stressful experience by reducing the financial strain. Maintaining a safety net that would help protect families from financial ruin would not only help ease the stress of job loss, but would have multiple fiscal benefits, including keeping workers in the job market. Till von Wachter, associate professor of economics at Columbia University noted at the conference that long-term unemployed workers, especially those with health problems, often file for Social Security disability insurance, a program that is far more expensive than unemployment insurance.