Issue Brief #228

Since 1938 the federal government has set a minimum value for an hour’s work. This has been an important policy supporting the wage levels of low-wage workers and establishing a floor below which Congress will not let wages fall. The last time Congress adjusted the minimum wage was nine years ago in 1997. Over the intervening years, the minimum wage has lost much of its effectiveness, as its real purchasing power has fallen to historically low levels.

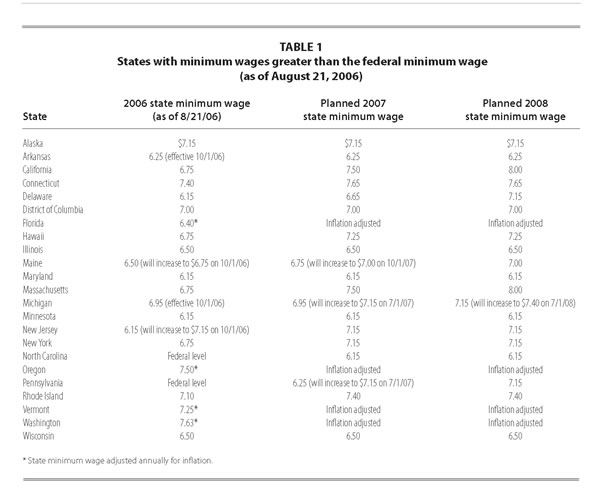

In response to these nine years of federal inaction, many states, comprising a majority of the nation’s workforce, have recognized the importance of a wage floor that supports low-wage work while at the same time not hurting the job prospects of low-wage workers. Currently 22 states plus the District of Columbia have increased their minimum wages above the federal rate of $5.15 per hour. Fifty-eight percent of the total U.S. workforce lives in one of these states with a minimum wage that has been set above the federal rate. This year alone, 10 states, including Arkansas and Michigan, have passed measures to increase their minimum wages. Six states, including Missouri, are expected to have an initiative on the November ballot to allow voters to decide whether the minimum wage should be raised. Missouri’s ballot initiative would raise the state minimum wage to $6.50 per hour on January 1, 2007 and index it annually to inflation thereafter.

Despite opponents’ claims that increases in the minimum wage lead to job losses, the empirical evidence doesn’t bear this out. In fact, following that 1996-97 federal minimum wage increase, the low-wage labor market performed better than it had in decades (e.g., lower unemployment rates, increased average hourly wages, increased family income, decreased poverty rates). In addition, the many minimum wage changes at the state-level have given economists a rare opportunity to do before-and-after comparisons to gauge the effect of the policy. These studies show the policy has its intended effect: it lifts the earnings and incomes of low-wage workers and their families, without generating job losses.

Over one-quarter of a million low-wage workers would benefit

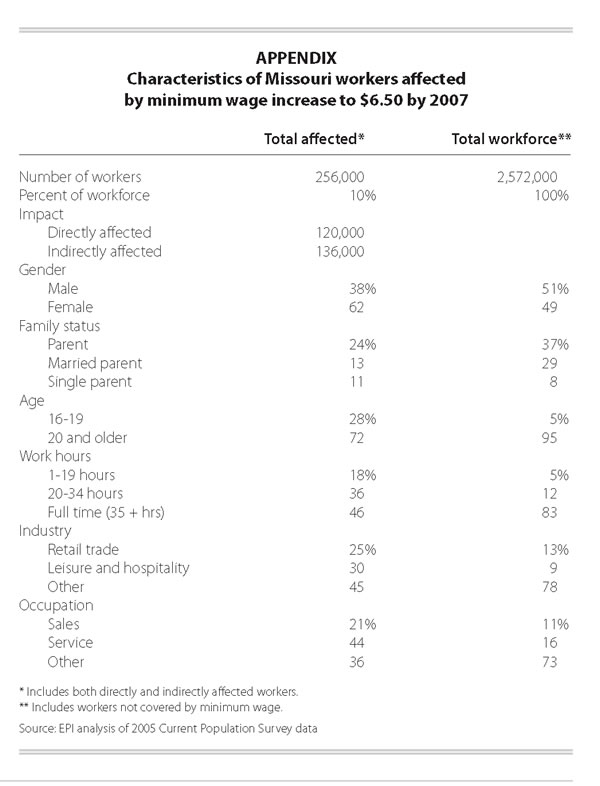

Missouri’s proposed minimum wage increase to $6.50 per hour would raise wages for 256,000 Missouri workers—10% of the state’s workforce. Directly affected are 120,000 workers who, without the increase, would earn between $5.15 and $6.50 in 2007. An additional 136,000 workers who are projected to earn more than $6.50 would also likely receive a modest wage increase, as employers adjust pay scales to accommodate raises for minimum wage workers.1

Adults, full-time workers, older workers, and children would benefit

Analysis of the 2005 Current Population Survey reveals that the workers potentially affected by a minimum wage increase are mainly adults who work full-time and provide significant income to their families. A boost in the Missouri minimum wage would also affect the 102,000 children of these workers.

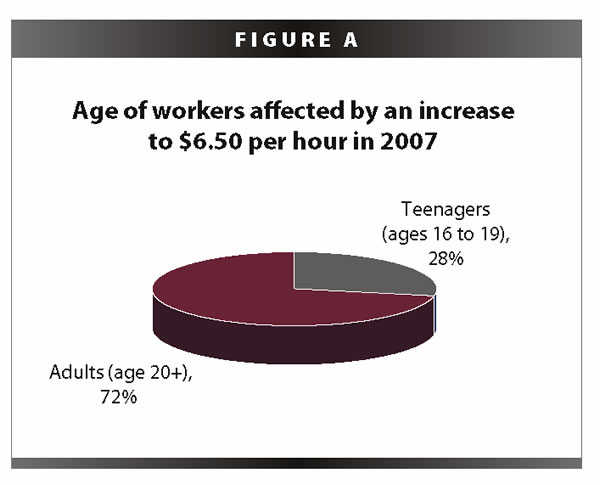

- Analysis of the proposed Missouri minimum wage increase finds that the vast majority (72%) of workers affected are adults aged 20 and above. (Figure A)

- About 43,000 workers, or 17% of those who stand to benefit from the minimum wage increase, are above age 50.

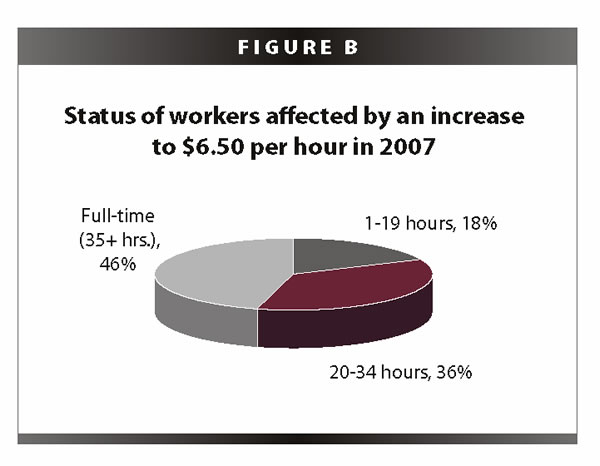

- Nearly half (46%) of workers who would be affected by this increase are full-time workers (35 hours or more per week). An additional 36%—91,000 workers—work half-time or more (20-34 hours per week).(Figure B)

- While Missouri’s workforce is fairly evenly split between male (51%) and female (49%) workers, the beneficiaries of a minimum wage increase are disproportionately female (61%). This is due to the fact that more women work in low-wage occupations and industries.

A minimum wage increase would improve standards of living

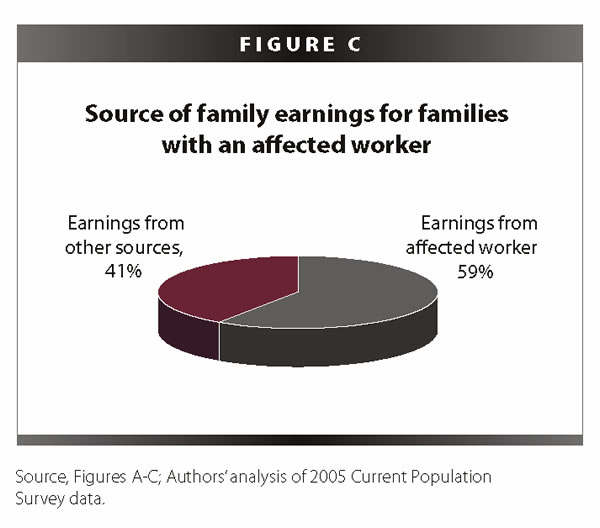

- The earnings of Missouri’s minimum wage workers are essential to their families’ total income. On average, families with affected workers rely on those workers for over half (59%) of the families’ total earnings.(Figure C)

- Nearly half (46%) of all families with an affected worker rely solely on the earnings from affected workers.

- Over 100,000 children of low-wage workers would see their parents’ income increase if the minimum wage is increased to $6.50 per hour.

- Today, the earnings of a full-time minimum wage worker (working 40 hours/week, 52 weeks/year) with a family of three would fall 35.5% below the official 2006 federal poverty level of $16,600. While the federal poverty line is an inadequate measure of the income needed to support a family, this comparison highlights the severe insufficiency of the current minimum wage.2 Despite the inadequacy of the minimum wage to support a family, nearly half of families with workers who would benefit from an increase receive their sole earnings from those workers.

Raising Missouri’s minimum wage would partially restore its purchasing power

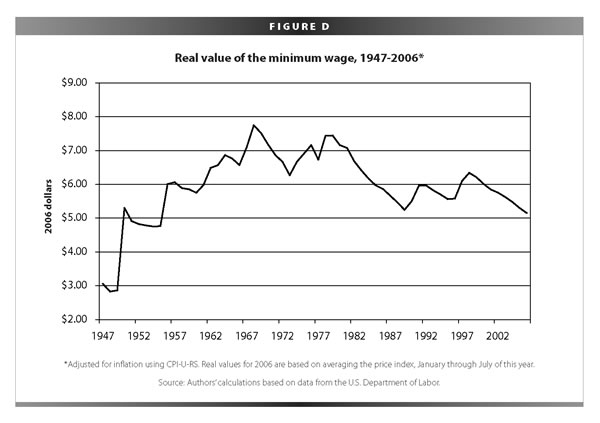

Missouri’s minimum wage is currently tied to the federal rate of $5.15 per hour, or $10,712 for a full-time, year-round worker. Since the minimum wage was first passed by Congress in 1938, it has required regular increases to account for the rising cost of living. However, after nearly the longest stretch of federal inaction since the bill’s inception, the minimum wage currently stands at its lowest real value in over 50 years (see Figure D). As the price of other goods has increased over time, the minimum wage has failed to keep pace. Raising Missouri’s minimum wage to $6.50 per hour and tying future annual increases to inflation would help reverse the trend of declining real wages for low-wage workers and ensure that future inflation does not erode the value of their paychecks.

Currently, 22 states and the District of Columbia have minimum wages higher than the federal rate of $5.15 per hour that is in effect in Missouri. In the Midwest, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota all have minimum wages above Missouri. Nationally, 17 states already have laws in effect that require their minimum wages to be at or above the $6.50 level being proposed for Missouri in January 2007, and several other states are actively considering such increases. Four states have decided to take future adjustments to the minimum wage out of the political sphere: Washington, Oregon, Vermont, and Florida all annually index their minimum wages to account for the rising cost of living. Ballot initiatives in Ohio, Colorado, Montana, Nevada, and Arizona all introduce similar indexing safeguards. (Table 1)

Raising the minimum wage would not cause job losses

Minimum wage opponents often say that higher minimum wages will yield substantial job losse

s, but empirical evidence does not support this claim. A 1998 Economic Policy Institute study failed to find job loss associated with the 1996-97 minimum wage increase.3 In fact, following that minimum wage increase, the low-wage labor market performed better than it had in decades (e.g., lower unemployment rates, increased average hourly wages, increased family income, decreased poverty rates).

This reality is leading many economists to support minimum wage increases as a useful policy measure, especially in an era of increasing economic inequality. In October 2004, 526 economists signed a statement that said, in part, that “a modest increase in the minimum wage would improve the well-being of low-wage workers and would not have the adverse effect that critics have claimed.” This list of economists included four Nobel Prize winners in economics and three past presidents of the American Economics Association.4

Most telling, however, are the experiences of the states that have raised their minimum wages over the last nine years, since they have given researchers a rare opportunity in empirical economics. 5 In essence, researchers have been able to compare states with minimum wage increases to similar states with no increase. These studies typically find that the job losses predicted by opponents have never materialized, and job growth has not been dampened in the 22 states with minimum wages higher than the federal level.

A study by the Fiscal Policy Institute found that “between 1998 and 2004, the job growth for small businesses in states with a minimum wage higher than the federal level was 6.2% compared to a 4.1% growth rate in states where the federal level prevailed.”6 Similarly, in 2003, a study by the Center for Urban Economic Development examined the economic impact of the Illinois minimum wage and found no significant correlation between minimum wages and employment growth.7

Further evidence supports the finding that modest minimum wage increases have had no negative effects because employers are often able to offset the small cost increase through higher productivity, lower recruiting and training costs, decreased absenteeism, and increased worker morale. These findings are supported by earlier research from Princeton economists David Card and Alan Krueger.8

The weight of the empirical evidence clearly shows that increasing Missouri’s minimum wage will have no negative effects, while increasing the standard of living for low-wage families. In public opinion polls, 80% of the population consistently supports an increase in the minimum wage.9 At the ballot box, minimum wage proposals have seen similar levels of support. In 2004, minimum wages on the ballot received 70% of the vote in Florida and 68% in Nevada.10 Raising Missouri’s minimum wage to an indexed $6.50 would benefit 256,000 workers, bring many workers up to a level that could support a family, and ensure that future inflation does not erode the value of low-wage workers’ paychecks.

Endnotes

1. Economic literature as well as EPI’s own economic modeling indicates that an increase in the minimum wage will have a modest but significant impact on the wages of workers earning just above the new minimum wage. EPI’s model projects future employment and wage trends on a state-by-state basis and thus allow projections of the number of workers who would gain from the spillover effect. For more detail on the methodology see Chapman, Jeff and Liana Fox, The Wage Effects of Minimum Wage Increases, Washington, D.C.: Economic Policy Institute (forthcoming).

2. For a more accurate measure of cost of living, see EPI’s Basic Family Budget Calculator: http://www.epi.org/content.cfm/datazone_fambud_budget

3. Bernstein, Jared and John Schmitt. 1998. Making Work Pay: The Impact of the 1996-1997 Minimum Wage Increase. Washington, D.C.: Economic Policy Institute. http://www.epi.org/content.cfm/studies_stmwp

4. Economists’ Statement. October 2004. It’s Time for a Raise. http://www.epi.org/minwage

5. For example: California Budget Project (February 2006) Minimum Wage Increases Boost the Earning of Low-Wage California Workers. Chapman, Jeff (May 2004) Employment and the minimum Wage: Evidence From Recent State Labor Market Trends. Economic Policy Institute. Fiscal Policy Institute. (April 2004) State Minimum Wages and Employment in Small Businesses, Fiscal Policy Institute (January 2004) Raising the Minimum Wage in New York: Helping Working Families and Improving the State’s Economy, Fiscal Policy Project a program of New Mexico Voices for Children (January 2006). An Economic Success Story: Job Growth and Poverty Reduction in States That Have Raised the Minimum Wage, Michigan League for Human Services (November 2005) A State Minimum Wage Helps Working Families Without Hurting Jobs, Oregon Center for Public Policy. (September 2005). Minimum Wage Employers Posting Strong Job Growth, Oregon Center for Public Policy (March 2001). Getting the Raise They Deserved: The Success of Oregon’s Minimum Wage and the Need for Reform, Pollin, Robert, Mark D. Brenner, and Jeannette Wicks-Lim (2004). Economic Analysis of the Florida Minimum Wage Proposal, Political Economy Research Institute. Watkins, Marilyn (January 2004) Still Working Well: Washington’s Minimum Wage and the Beginnings of Economic Recovery, Economic Opportunity Institute.

6. Fiscal Policy Institute. March 2006. “States with Minimum Wages Above the Federal Level Have had Faster Small Business and Retail Job Growth.” http://www.fiscalpolicy.org/FPISmallBusinessMinWage.pdf

7. Ron Baiman, Marc Doussard, Sharon Mastracci, Joe Persky, Nik Theodore. March 2003. “Illinois Minimum Wage Study.” Center for Urban Economic Development, University of Illinois at Chicago. http://www.uic.edu/cuppa/uicued/Publications/RECENT/MinimumWageStudy.pdf

8. Card, David, and Alan Krueger (1994) “Minimum wages and employment: A case study of the fast-food industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania.” American Economics Review. Vol. 84, No. 4, pp. 487-96; Card, David, and Alan Krueger (1995) Myth and measurement: The new economics of the minimum wage. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press; Card, David, and Alan Krueger (1998) “A reanalysis of the effect of the New Jersey minimum wage increase on the fast-food industry with representative payroll data.” Cambridge, Mass.: NBER.

9. Pew Research Center for the People & the Press. “Maximum Support for Raising the Minimum.” April 19, 2006. http://pewresearch.org/obdeck/?ObDeckID=18

10. According to Nevada’s constitution, an amendment must pass twice before it goes into effect. The Nevada minimum wage amendment will be ratified into law if passed by voters again in November.