Briefing Paper #389

Introduction and executive summary

The Federal Reserve’s policies affect almost every important aspect of the economy. Given the gradual strengthening of the economy after the Great Recession, there is now talk of normalizing monetary policy and raising interest rates. That conversation is important, but it is also too narrow and keeps policy locked into a failed status quo. There is need for a larger conversation regarding the entire framework for monetary policy and how central banks can contribute to shared prosperity. It is doubtful the United States can achieve shared prosperity without the policy cooperation of the Fed. This makes activist engagement with the Fed and its policies a matter of the highest importance.

Full employment, shared prosperity, and the Federal Reserve

Full employment is the bedrock of shared prosperity. Working families need jobs to provide income, and full employment ensures that jobs are available for all. Full employment also creates an environment of labor scarcity in which workers can bargain for a fair share of productivity gains, making full employment essential for decent wages. A major factor behind the wage stagnation of the past 30 years is that the U.S. economy has been far from full employment for most of this time.

Full employment is also relevant for union bargaining power, and unions are unlikely to achieve their principal institutional objectives—organizing and bargaining—without full employment. Consequently, full employment should be a major concern of unions for reasons of both social solidarity and institutional interest.

Federal Reserve policy is absolutely critical for attainment of full employment, and the Fed is legally mandated to pursue policies that promote maximum employment with price stability. However, it has not been doing so for the past 35 years, preferring to emphasize price stability (i.e., inflation) on grounds that full employment will take care of itself if inflation is low and stable.

The Fed’s retreat from full employment has been part of a general retreat by the Washington policy establishment, including both Republicans and elite Democrats who control the Democratic Party. The labor movement and working-family activists must wholeheartedly embrace the issue of full employment and compel both Washington and the Fed to make it the nation’s foremost economic priority.

There is an irony to the current moment. Even though the Fed has failed in the past to live up to its obligations, it is now the only major Washington policy institution that is even tipping its hat to the issue of full employment. Though the Fed should be credited for its new awareness, it is critical not to forget its past inclinations. Those inclinations remain very much alive within the institution and ready to surface.

Labor and working-family activists need a strategy to ensure the Fed’s renewed concern with full employment is translated into policies that deliver. The strategy should have an inside and outside dimension. The inside dimension entails constructive informed engagement at a senior level within the Federal Reserve System. The outside dimension requires bringing popular pressure from Main Street to Congress to bear on the Fed.

The strategy must also go beyond the Fed and into the Democratic Party, which must also come to view full employment as the country’s most important economic policy priority. Democrats must be stripped of the “Clinton fig leaf” of the 1990s. In the late 1990s the United States experienced a brief period of full employment during which wages rose. That period clearly showed the benefits of full employment, but it was bubble-driven and unsustainable. The goal is to insist on sustainable full employment supported by rising wages and real investment. The Clinton fig leaf is a major obstacle because many Democrats invoke the period to justify a return to past policies, despite their having proved unstable and unsustainable.

Policy challenges and threats

Convincing the Fed to adopt full employment policies requires persuading it to change its policy framework. In the meantime, there is an omnipresent danger that the Fed will prematurely tighten monetary policy in the name of preventing inflation, despite the fact the economy is far away from full employment. To lay the foundation for full employment, the Fed should adhere to the following precepts:

- Rehabilitate full employment as the country’s foremost policy priority. The central policy challenge is to rehabilitate full employment as the preeminent policy priority. That raises the question of defining full employment. Paraphrasing Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart, full employment is difficult to define, but you know it when you see it. Full employment is likely attained when the unemployment rate is low, job vacancies are plentiful so workers can find jobs easily, the inflation rate is around 3 percent, and real wages are rising at the rate of productivity growth. For the United States, such a configuration of outcomes is associated with unemployment rates below 5 percent. That happened in 2007 and the late 1990s, and before that in the early 1970s, which shows how rare full employment has been—and how far away it still is.

- Abandon the 2 percent inflation target. A second policy challenge is to get the Fed to abandon its 2 percent inflation target. A large multi-sector economy is likely to have inflation above 2 percent at full employment because of differences in conditions across sectors. The 2 percent inflation target represents a cruel trap. As the unemployment rate comes down, the economy will inevitably bump against the self-imposed inflation ceiling, which likely coincides with an unemployment rate around 5.5 percent. Given its inflation target, the Federal Reserve will then have reason to pull the trigger and raise interest rates to slow the economy, thereby trapping millions in unemployment and ensuring continued wage stagnation.

- Stop the war on wages. A third policy challenge is to get the Fed to abandon its de facto war on wages, which is reflected in the Fed’s shortchanging of full employment and its adoption of a 2 percent inflation target. The war on wages rests on a faulty understanding that portrays wages as just a cost to the economy. The reality is wages are the principal purpose of the economy, which is to generate a decent standard of living for all. Rising wages are also needed to make the economy work. Economies where wages lag productivity growth are marked by higher income inequality. They are also prone to demand shortfalls, which cause economic stagnation as demand fails to keep pace with supply. That is the principal cause of the current economic malaise.

The Fed must abandon its focus on the employment cost index (ECI), which gives monetary policy an anti-wage tilt by encouraging the Fed to raise interest rates whenever wage growth accelerates. Because the share of corporate income accounted for by profits is at a record high, it is possible wages can rise for quite a while without inflation if firms are forced to accept profit margin compression as the bargaining power pendulum swings back toward workers.

- Resist calls for preemptive interest rate hikes to prevent inflation. An omnipresent policy threat is the push by inflation hawks to raise interest rates as a preemptive strike against future inflation. The reality is economists do not know when inflation will accelerate, but preemptively raising interest rates increases the likelihood that the economy will stop short of full employment. That will strangle wage growth, entrench income inequality, and impose hardship on millions of working families. Instead, the Fed should adopt a “test the waters” approach to policy that allows the economy to edge forward until inflation is seen to reach an unacceptable level. That will enable the economy to reach full employment and wages to grow.

- Do not underestimate unemployment and labor market slack. A second threat is the Fed may underestimate the degree of unemployment and labor market slack and use its underestimate to justify raising interest rates. One danger is the Fed may misunderstand the huge numbers of workers who have left the labor force because of poor job prospects, and mistakenly think this labor force exit is permanent. A second danger is that the Fed may mistakenly see the increase in long-term unemployment as permanent and view these workers as unemployable, thereby justifying the view that labor markets are tighter than reported. The fact is the long-term unemployment rate has been steadily coming down with job growth, which shows these workers take jobs when jobs are available. The sensible thing to do is continue with job-friendly monetary policy and see if the unemployment rate continues coming down. That is the logic of a “testing the waters” approach.

- Restore quantitative monetary policy. In addition to changing its policy framework, the Federal Reserve must also change its policy toolbox. Today, monetary policy is largely viewed through the lens of setting interest rates. Interest rate policy is a blunderbuss that hits the whole economy, with particularly strong effects on the manufacturing sector. Policymakers need other tools that can finely target particular problem areas (such as asset price bubbles) without inflicting collateral damage on the rest of the economy. Successful monetary policy requires quantitative policy instruments such as margin requirements, reserve requirements, and regulation. Such policy tools have been largely discarded owing to the neoliberal takeover of economic policy. That has made managing the economy more difficult. It is time for the Federal Reserve to revive the use of margin requirements and introduce new policy tools such as asset based reserve requirements (ABRR).

- Reform exchange rate policy. Another area where change is needed is exchange rate policy. Exchange rates have an enormous impact on the economy via their impact on the trade deficit and the manufacturing sector, and that impact has increased with globalization.

Exchange rate policy is formally controlled by the Treasury, but the Fed is also deeply implicated. For the past 25 years the Treasury has done an awful job with exchange rate policy, which has been managed on behalf of multinational corporations and financial-sector interests, with little regard for the impact on working families.

The existing policy setup has created a Kabuki theatre that allows the pretense that the Fed, the Treasury, and exchange rates are unconnected. Given its awful performance, Congress should consider stripping the Treasury of its responsibility for exchange rate policy and moving responsibility to the Fed with strict congressional accountability attached. Exchange rates and interest rates are joined at the hip, and policy should be properly coordinated.

In the meantime, exchange rate concerns should be raised with the Fed by asking how the Fed factors exchange rates into its interest rate setting, and how it takes account of the impact of interest rates on the exchange rate.

- Finance public infrastructure investment. The Fed should also be permitted to help finance public infrastructure investments. Such financing of infrastructure investment would raise growth by relaxing the financing constraint that currently unduly restricts such investment. One possibility is this could be done by creating a national infrastructure bank whose bonds the Fed could purchase. A second possibility is that a new federal agency, similar to Fannie Mae, could be created to securitize state and local government infrastructure bonds, and the Fed could then buy those securitized bonds.

Institutional concerns and policy engagement

The Fed is biased against working families. That bias reflects both the Fed’s specific hardwired institutional characteristics and the political characteristics of the time. With regard to institutional characteristics, the Fed’s legal setup means it is significantly influenced by the banking industry, and it is also prone to regulatory capture by the banks it is supposed to regulate. With regard to the politics of the time, the neoliberal capture of the economics profession and society’s understanding of the economy imparts an intellectual bias to the views of policymakers and the advice of the Federal Reserve’s economic staff.

The combination of the importance of Fed policy and the biases within the institution makes countervailing activist engagement with the Fed a critical necessity. Engagement should include high-level policy conversations with Federal Reserve principals, Main Street activism to pressure Federal Reserve decisionmaking, lobbying of Congress and the administration to ensure the appropriateness of Federal Reserve appointees, lobbying Congress to ensure tough oversight hearings regarding Federal Reserve policy, and lobbying the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors to ensure progressive appointees as Federal Reserve regional bank Class C directors.

Why the Federal Reserve matters, and why working-family advocates should engage it

The Federal Reserve, widely referred to as “the Fed,” is one of the most powerful economic institutions in the United States and in the world. Its policies and actions affect interest rates, the stock market, the quantity and allocation of credit, and the exchange rate, to name just a few of the critical variables it impacts. Those variables in turn affect the employment and unemployment rate, the rate of economic growth, income distribution, wages, the trade deficit, the budget deficit, Social Security solvency, the housing market, construction employment, manufacturing employment, and many other economic outcomes.

Additionally, as one of the nation’s preeminent economic policy institutions, the Fed has enormous influence on the overall national economic policy conversation via its bully pulpit and via the hundreds of senior economists it employs. For instance, former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan was a booster of globalization, fiscal austerity, Social Security benefit cuts, and deregulation, and he did great damage by using his pulpit to push those views. In contrast, new Fed Chairwoman Janet Yellen has had a positive progressive impact by using her pulpit to direct attention to the continuing high rate of unemployment and shortage of jobs.

These observations illustrate the enormous economic power and importance of the Fed. Without its policy cooperation, it is unlikely the nation can achieve shared prosperity. That, in a nutshell, is why the Fed is important, matters to all of us, and should be of special importance to working-family advocates.

Yet, in recent decades the Fed and its policies have not been the focus of the same intense progressive scrutiny as other vital policy concerns, such as globalization. The reasons for this relative neglect are multiple. First, the Fed’s policy focus is monetary and financial policy, which can be highly technical. Those technicalities can discourage engagement by both the general public and politicians. Second, there may be a sense that finance is “super-structural” and the real foundations of the economy are elsewhere, and that the Fed is thus not deserving of attention. Indeed, on both left and right, there is a line of economic thought that maintains this view. Among conservative economists there is a view that money is just a “veil” over the “real” economy, while leftist economics can fall into a similar trap that holds the real rate of profit is all important and monetary policy has no effect on it. Trade unionists have also been prone to a similar fallacy, believing that the role of unions is organizing and bargaining and that these core activities are unconnected to the Fed. Third, concerns like globalization are driven by legislation (e.g., free trade agreements), whereas monetary policy is the product of ongoing Federal Reserve deliberations; as such, calls for action against discrete pieces of legislation are an easier activist play than calls for permanent engagement with a particular policy process. Lastly, the Fed is a somewhat mysterious institution. On the one hand, it is in the news all the time; on the other hand, little is known about it and its governance structure. That mysterious character provides the Fed with a shield that deflects scrutiny and attention.

All of these factors contribute to explaining the relative lack of progressive engagement with the Fed. That contrasts with the business and financial community, which has strong institutionally formalized links within the Fed that enable business and finance to influence Fed policy. In part, those business-friendly links are hardwired into the Fed via its legal structure (discussed later), but in part they reflect the greater attention paid to the Fed by finance and business. The important lesson is working-family advocates need to pursue sustained policy engagement with the Fed. Such an engagement is desirable on its own merits, but it is doubly desirable because of the need to counter existing “big finance – big business” biases within the Fed. The goal of this guide is to facilitate and inform that engagement.

Full employment, shared prosperity, and the Federal Reserve

Full employment is the bedrock of shared prosperity. Working families need jobs to provide income, and full employment ensures that jobs are available for all. Full employment also creates an environment of labor scarcity in which workers can bargain for a fair share of productivity, making it essential for decent wages. A big reason for the wage stagnation of the past 30 years is that the U.S. economy has been far away from full employment for much of the time.

This importance of full employment for bargaining makes it relevant for unions. Though unions have additional bargaining power that comes from their existence, unions will face headwinds in the absence of full employment. Weak labor markets mean firms can threaten to replace unionized workers with nonunionized workers, and firms also have an incentive to build new nonunionized plants. Furthermore, weak labor markets create tensions between union and nonunion workers by allowing firms to fan resentment of the better wages and employment conditions of unionized workers. Consequently, full employment should be a major concern of unions for reasons of both social solidarity and institutional interest.

The Federal Reserve and full employment

Federal Reserve policy is absolutely critical for attainment of full employment. That puts the Fed at the epicenter of the issue and explains why the Federal Reserve must be a central focus of labor movement and working-family activism.

Fortunately, there is a natural and easy avenue of engagement because the Federal Reserve is legally mandated (under the Humphrey-Hawkins Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act of 1978) to pursue policies that promote maximum employment with price stability. However, the Fed has not been doing that for the past 35 years, preferring to emphasize concerns with inflation. That policy preference has been justified by the claims of neoliberal economists that full employment will take care of itself if inflation is low and stable.

The Fed’s retreat from concern with full employment has been part of a general retreat by the entire Washington policy establishment. After World War II through to the mid-1970s, full employment was the central goal of national economic policy. Today, it is not at the center of either the Republican agenda or the agenda of elite Democrats who control the Democratic Party. The labor movement and working-family activists must wholeheartedly embrace the issue of full employment and compel both Washington and the Fed to make it the nation’s foremost economic priority.

Irony of the moment and need for a strategy

There is an irony to the current moment. Even though the Fed has failed in the past to live up to its obligations, it is now the only major Washington policy institution that is even paying lip service to the issue of full employment. That new stance reflects the influence of Janet Yellen, the recently appointed Federal Reserve chairwoman, which shows the importance of politically influencing Federal Reserve appointments. However, while the Fed should be credited for its new awareness, it is critical not to forget its past inclinations. Those inclinations remain very much alive within the institution and ready to surface.

Labor and working-family activists need a strategy for solidifying the Fed’s renewed concern with full employment to ensure this concern is translated into policies that deliver desired real-world outcomes. The strategy should have an inside and outside dimension. The inside dimension entails constructive informed engagement at a senior level within the Federal Reserve system. The outside dimension consists of popular pressure involving action from Main Street to Congress.

The strategy must also go beyond the Fed and include the Democratic Party, which must also be made to view full employment as its foremost economic policy priority. Any Democrat seeking to become president must be willing to explicitly and publicly endorse full employment and explain the policies necessary for achieving it.

Democrats must be stripped of the “Clinton fig leaf” of the 1990s. In the late 1990s the United States experienced a brief period of full employment during which wages rose. That period clearly showed the benefits of full employment, but it was bubble-driven and unsustainable. The goal now is to insist on sustainable full employment driven by rising wages and real investment, and not full employment driven by asset market speculation and credit bubbles. The Clinton fig leaf is a major obstacle because many Democrats invoke the 1990s to justify a return to past policies, despite the fact those policies have proved unstable and unsustainable.

Policy challenges and threats

Getting the Fed to adopt full employment policies confronts several challenges and threats. The challenges concern permanently changing the Fed’s policy framework. The threats are the risk that the Fed may tighten current policy in an anti–full employment manner. In particular, there is an omnipresent danger that the Fed prematurely tightens monetary policy in the name of preventing inflation, despite the fact the economy is far from full employment.

Restore “full employment” monetary policy

To restore monetary policy that supports the goal of full employment, the Federal Reserve must rehabilitate full employment as the number one policy priority, abandon the 2 percent inflation target, stop the war on wages, resist the call for preemptive rate hikes to prevent inflation, and accurately gauge the extent of unemployment and labor market slack.

Rehabilitate full employment

With regard to the policy framework, the central challenge is to rehabilitate full employment as the number one policy priority.1 The 30 years after World War II witnessed an era of shared prosperity that is now widely referred to as the “golden age.” Spurred by memories of the Great Depression and the insights of Keynesian economics, full employment was made the dominant policy goal. In the 1970s, under the pressure of higher inflation caused by the OPEC oil shocks and labor–capital conflict over income distribution, the focus on full employment was abandoned and replaced with a focus on controlling inflation. Among economists, the shift of policy focus was justified by the theories of Milton Friedman, who argued that the economy quickly and automatically restores full employment on its own, and that monetary policy cannot affect employment, wages, and growth and can only affect inflation. Given that, it made sense for policy to focus exclusively on targeting low inflation—and the Federal Reserve strongly bought into this way of thinking.

That policy shift has been disastrous for working families because full employment is the sine qua non for shared prosperity. All working families need jobs and, over the last 40 years, real wages have only risen significantly when there has been full employment. This makes rehabilitating full employment a critical issue of our time.

That raises the question of how to define full employment, to which working-family advocates must have an answer. The conventional definition is labor demand equal to labor supply. However, in reality, there is always some unemployment owing to frictions that prevent firms and workers from matching up. It takes time for job seekers to find the right job and time for firms to find the right worker; jobs and workers may also be in different locations. Consequently, there is always some frictional unemployment at full employment.2 However, this is a useless policy guide because of difficulty distinguishing frictional unemployment from other unemployment. That means we need other measures to define full employment.

A second definition of full employment (Keynes 1936) is a situation where there is no employment gain in response to increased demand for goods and services. In a large economy with many sectors, that implies inflation will likely be above 2 percent at full employment because increased demand will create jobs in sectors with unemployment, but raise prices in sectors at full capacity. This Keynesian definition spotlights the importance of the debate over what constitutes acceptable inflation. Policymakers who argue for an inflation target of 2 percent or less are implicitly arguing against full employment. In normal times, a full employment inflation target should be 3 or even 4 percent.

A third definition of full employment is a situation where the number of job vacancies equals the number of unemployed.3 According to this easily understandable and operational definition, the United States is still far from full employment. In November 2014 there were 5 million job openings and 9.1 million unemployed, without even counting workers who wanted full-time work and could not find it, or workers who had left the labor force for lack of job opportunities.

A fourth definition of full employment is a situation where real (i.e., purchasing power) wages rise at the rate of productivity growth (Palley 2007). That means money wages increase at the rate of inflation plus productivity. The rationale is workers only share in productivity growth when they have bargaining power, which requires full employment. Ergo, rising real wages is an indication of full employment. However, today, even this definition risks stopping short of full employment because real wages have lagged productivity growth for years. This has created room for catch-up, so real wage growth can exceed productivity growth for a while as profit margins return to more normal levels.4

However, the best definition encompasses all of the foregoing definitions: the unemployment rate is low, job vacancies are plentiful so workers can find jobs easily, the inflation rate is around 3 percent, and real wages are rising at the rate of productivity growth. For the United States, such a configuration of outcomes is associated with unemployment rates below 5 percent. That happened in 2007 and the late 1990s, and before that in the early 1970s, which shows how rare full employment has been—and how far away it still is.

Sustained full employment is possible with policies that strengthen demand and wage formation, contain the trade deficit, and restrain financial market excess. The problem is Wall Street vigorously opposes an economy in which wages grow with productivity, profit margins are reduced, and the license of globalization and speculation is revoked. Consequently, Wall Street aims to short-circuit the possibility of sustained full employment by demanding the Federal Reserve enforce a 2 percent inflation target. This shows politics is the real obstacle to rehabilitating full employment, and it calls for a bright political spotlight on Federal Reserve appointments and policy actions. That spotlight is needed to help check Wall Street’s demands.

Abandon the 2 percent inflation target

A second needed change in the policy framework is to get the Fed to abandon its 2 percent inflation target. As argued above, a large multisector economy is likely to have higher than 2 percent inflation at true full employment because of differences in conditions across sectors. However, driven by the mistaken economics of Milton Friedman, the Federal Reserve has now adopted a 2 percent inflation target. That target creates a policy trap that will prevent full employment. In doing so, it will also undercut the possibility of future wage increases despite ongoing productivity growth, and that promises to aggravate existing problems of income inequality.

The Fed’s inflation target is analytically and tactically flawed. Analytically, its inflation target is too low and will inflict significant future economic harm. Tactically, at this time of global economic weakness, the Federal Reserve should be advocating policies that promote rising wages rather than focusing on inflation targets.

The 2 percent inflation target represents a cruel trap: As the unemployment rate comes down, the economy will inevitably bump against the Federal Reserve’s new self-imposed inflation ceiling. That ceiling likely coincides with an unemployment rate of around 5.5 percent or higher. Given its inflation target, the Federal Reserve will then have reason to pull the trigger and raise interest rates, thereby trapping millions in unemployment and ensuring continued wage stagnation.

There is little reason to believe a 2 percent inflation target is best for the economy. Those economists who claim it is are the same economists who should have been discredited by the 2008 financial crisis and the economic stagnation that has followed. Instead, there are strong grounds for believing a higher inflation rate of 3 to 5 percent produces better outcomes by lowering the unemployment rate and creating labor market bargaining conditions that help connect wages to productivity growth.

The Federal Reserve’s 2 percent inflation target constitutes a backdoor way of forcing society to live with a “new normal” of permanent wage stagnation and unemployment above that consistent with full employment. In effect, by adopting this target, the Fed has surreptitiously abandoned its legislated mandate to also pursue “maximum employment.”

The Fed’s adoption of a 2 percent inflation target has de facto redefined “price stability” as “inflation stability.” Given that, its Humphrey–Hawkins mandate should be understood as the pursuit of maximum employment consistent with inflation stability. That mandate would be best fulfilled by pursuing a higher stable inflation rate of 3 percent or more. The current 2 percent inflation target shortchanges the maximum employment component of the mandate.

Unfortunately, the political and economic logic of the moment makes it difficult to challenge the Fed. First, inflation is now so low that the public’s ear is not attuned to the threat of the 2 percent target. Second, in a period of wage stagnation, opposition to low inflation and support for higher future inflation can sound like support for higher prices. That is a misunderstanding. The opposition is to an excessively low inflation target that will permanently increase unemployment and prevent workers from bargaining for a fair share of productivity growth.

Stop the war on wages

A third needed change in the policy framework is to get the Fed to abandon its de facto war on wages, which is reflected in the Fed’s abandonment of full employment and its adoption of a 2 percent inflation target. The war on wages rests on a faulty understanding that portrays wages as just a cost to the economy, when the reality is wages are the principal purpose of the economy, which is to generate a decent standard of living for all.

Rising wages are also needed to make the economy work. That is a fundamental insight of Keynesian economics. Economies where wages lag productivity growth are marked by higher income inequality. They are also prone to demand shortages which cause economic stagnation as demand fails to keep pace with supply. That is the principal cause of the current economic malaise.

Wages can be too high and undercut profit needed for investment and growth, but they can also be too low and undercut demand. The perennial challenge is to find the right balance, avoiding a profit squeeze that undercuts investment and a wage squeeze that undercuts consumer demand. Unfortunately, modern mainstream economics tends to treat wages as exclusively a cost. That treatment is reflected in textbook tendencies to oppose minimum wages and trade unions and to ignore the demand effects of income distribution.

It also finds expression in monetary policy paranoia about wage inflation. That policy paranoia threatens to make itself felt via the Federal Reserve’s use of the employment cost index (ECI) as a preferred measure of inflationary pressure. Focusing on the ECI gives monetary policy an anti-wage tilt by encouraging the Fed to raise interest rates whenever wage growth accelerates.

The Fed’s focus on the ECI is fundamentally wrong for two reasons. First, because the share of corporate income accounted for by profits is at a record high, it is possible wages can rise for quite a while without inflation if firms are forced to accept profit margin compression as the bargaining power pendulum swings back toward workers. And even if the process of income redistribution triggers marginally higher inflation because profit margin compression does not occur smoothly across industries, it is not cause for worry, as a little bit of temporary inflation is good for a highly indebted economy.

Second, the ECI is significantly affected by rising worker health insurance costs. That means the Fed may implicitly let failures of the medical care system drive monetary policy, thereby allowing the failures of the medical care system to suppress employment and wages.

Resist the call for preemptive rate hikes to prevent inflation

The Fed’s existing policy framework (ignoring full employment, adhering to a 2 percent inflation target, and viewing rising wages as an inflationary threat) imposes an anti-worker bias. It also creates an imminent threat that the Fed will prematurely raise interest rates in a preemptive strike to head off inflation, thereby adversely affecting the employment situation.

The push to raise interest rates is being driven by the inflation hawks, who have long used the language of “preemptive strike” to justify their policy positions.5 The reality is economists do not know when inflation will accelerate, but raising interest rates preemptively increases the likelihood that the economy will stop short of full employment. That will strangle wage growth, entrench income inequality, and impose hardship on millions of working families.

The late 1990s offers valuable lessons for today. Back then there were also calls to raise interest rates preemptively. Fortunately, then–Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan adopted a “test the waters” approach to policy, allowing the economy to edge forward so that unemployment eventually fell below 4 percent. That inaugurated the strongest period of real wage growth over the past 30 years, and it was done with only modest increases in the core inflation rate, which was 2.4 percent in 2000.

Now, the Federal Reserve confronts a similar choice between “preemptive inflation tightening” that sacrifices wage growth and full employment, versus a “testing the waters” approach that gives wage growth and full employment a chance. This choice is couched in the technicalities of monetary policy. However, those technicalities obscure a deeper choice, which is whether policy is going to continue the war on wages, or whether policy will turn toward restoring shared prosperity by giving wage growth a chance.

Do not underestimate unemployment and labor market slack

A second imminent threat is the Fed may underestimate the degree of unemployment and labor market slack and use its underestimate to justify raising interest rates. One danger is the Fed may underestimate labor market slack by ignoring the huge numbers of workers who have left the labor force because of poor job prospects. This labor force exit is evident in the decline in the employment-to-population ratio. The percentage of Americans of working age with a job declined from 64.6 percent in January 2000, to 63.3 percent in January 2007, to just 59.2 percent in December 2014. Inflation hawks argue the decline is permanent and reflects retirements due to an aging population. According to them, that means the labor market is therefore tightening rapidly. However, that argument does not stand up to scrutiny because the reduction is similarly evident within the “prime-age” population (25–54), within which 81.8 percent were employed in January 2000, 80.3 percent were employed in January 2007, but only 77 percent were employed in December 2014. This shows the drop in the employment-to-population ratio is mainly due to a lack of jobs and not to retirement and demographic trends.

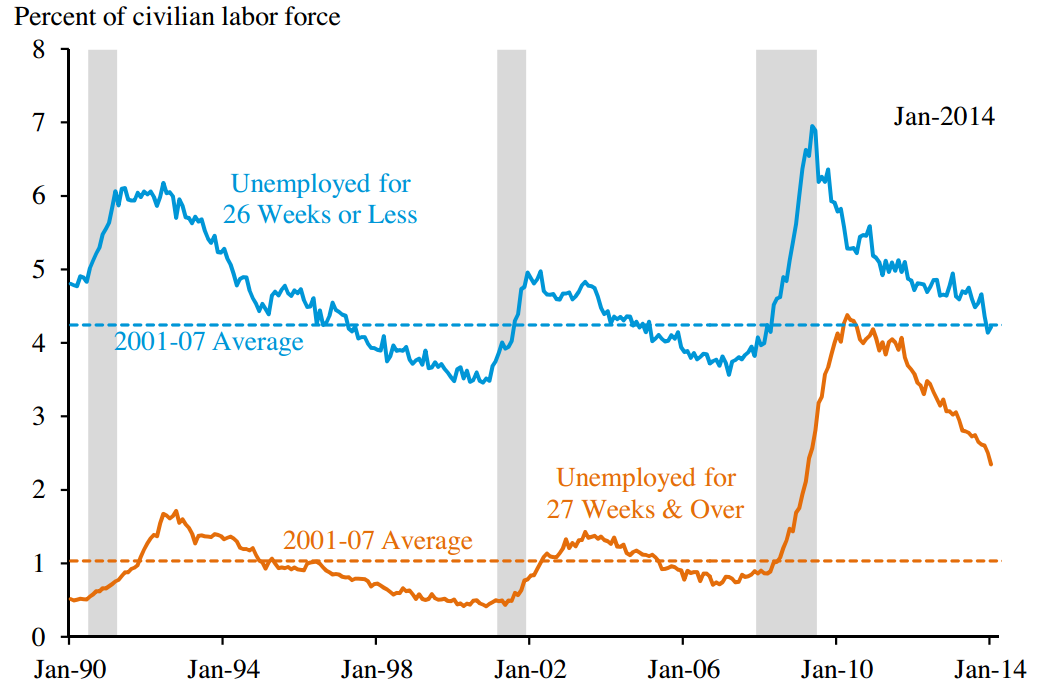

A second danger is that inflation hawks are arguing the increase in long-term unemployed is permanent and these are “damaged” workers whom firms do not want to hire. Consequently, for purposes of interest rate policy and inflation control, hawks argue the Fed should view the long-term unemployed as a form of phantom unemployment that is irrelevant for monetary policy. This argument is captured in Figure A, which is drawn from the 2014 Economic Report of the President. Figure A decomposes the unemployment rate into short term (26 weeks or less) and long term (greater than 26 weeks). It shows how short-term unemployment has returned to the rate prevailing before the Great Recession of 2008–2009, but long-term unemployment remains elevated. However, contrary to the hawks’ argument, the long-term unemployment rate has also been steadily coming down, which shows these workers take jobs when they are available. The proper and sensible thing to do is continue job-friendly monetary policy and see if the long-term unemployment rate continues coming down. That is the logic of a “testing the waters” approach. Raising interest rates without trying this would risk unnecessarily throwing away the opportunity for this good outcome.

Restore quantitative monetary policy

Not only must the Federal Reserve change its policy framework, it must also change its policy toolbox. Today, monetary policy is largely viewed through the lens of setting interest rates. However, in the heyday of the Keynesian revolution in economic policy after World War II, monetary policy was also guided by quantitative policy such as margin requirements and reserve requirements. Those policy tools were discarded as part of the neoliberal takeover of economic policy, and it has made managing the economy more difficult. It is time to bring back quantitative monetary policy.

Interest rate policy is a blunderbuss that hits the whole economy, with particularly severe effects on employment that are bad for working families. Policymakers need other tools that can finely target particular problem areas without inflicting collateral damage on the rest of the economy.

One tool is margin requirements on stock market purchases financed with credit. Those requirements require borrowers back part of their borrowings with cash. The margin requirement has been set at 50 percent since 1974 and has not been changed since then. In the 1950s, 1960s, and early 1970s, margin requirements were varied often as part of tamping down stock market speculation that contributed to economic destabilization. Such speculative destabilization has recurred continually over the past 30 years, and it is time to restore active use of margin requirements.

Not only does excessive stock market speculation have adverse macroeconomic effects, it also makes it hard for working families to plan for retirement. Over the last 30 years, policymakers have encouraged the replacement of defined-benefit retirement plans (i.e., traditional pensions) by defined-contribution plans (i.e., IRAs and 401Ks). A volatile, speculative stock market turns retirement into a lottery as working families risk overpaying for stocks in booms and then selling under financial distress in slumps. Using margin requirements to tamp down speculation that drives up equity prices is therefore good for the macro economy, and it is also good for the retirement system because it smooths equity prices.

Even more than reviving stock market margin requirements as a policy tool, there is need to add policy tools that stabilize the economy by targeting particular areas of imbalance. As mentioned above, interest rates are a blunderbuss. They are a good tool when the entire economy needs to be stimulated or restrained. However, when there are problems in a particular sector (e.g., housing or financial markets), using interest rates to address those problems can be very damaging to the rest of the economy.

Repeated stock market boom–bust cycles have prompted policymakers to look to reform the financial system to avoid future crises, but they remain fixated on capital standards because that is what is already in place. There is a better way to regulate financial markets through asset-based reserve requirements (ABRR), which consist of extending margin requirements to a wide array of assets held by financial institutions. ABRR require financial firms to hold reserves against different classes of assets, with the Federal Reserve setting adjustable reserve requirements on the basis of its concerns with each asset class.6

A system of ABRR would confer many benefits:

- It would provide a much-needed new set of policy instruments that can target specific financial market excesses, leaving interest rate policy free to manage the overall macroeconomic situation. That will increase the efficacy of monetary policy by enabling the Federal Reserve to target sector imbalances without resorting to the blunderbuss of interest rate increases. If the Fed is concerned about a particular type of asset bubble generating excessive risk exposure, it can impose reserve requirements on that specific asset without damaging the rest of the economy.

- It would help prevent asset bubbles. By requiring financial firms to retain some of their funds as non-interest-bearing deposits with the Fed, policymakers can affect relative returns on different categories of financial assets. If policymakers want to deflate a particular asset category, they can impose higher reserve requirements on that category, thereby reducing its returns and prompting financial investors and firms to shift funds out of that asset into other relatively more profitable asset categories.

- If the Federal Reserve wants to prevent a house price bubble it can impose higher reserve requirements on new mortgage lending, thereby raising the cost of mortgages without raising interest rates (raising interest rates would hurt investment and also hurt manufacturing by appreciating the exchange rate).

- ABRR provide a policy tool that can encourage public purpose investments such as inner city revitalization or environmental protection by setting low (or no) reserve requirements on such investments.

ABRR also offer an efficient, cost-effective way to normalize monetary policy after quantitative easing (QE). In the past, the Fed controlled interest rates by increasing and reducing the market supply of liquidity. As a result of QE, banks now have huge excess holdings of liquidity. In the future, the Fed plans to increase market interest rates by paying interest to banks on liquidity they deposit with the Fed. I have criticized that policy proposal as unnecessarily rewarding banks for a crisis they helped create (Palley 2014), and it is also costly for the federal budget because it will reduce the Fed’s profit paid to the Treasury. An alternative strategy to deactivate banks’ excess liquidity is to make them hold it by imposing ABRR.

The big takeaway is that quantitative monetary policy is effective and useful. However, it has been discarded because of neoliberal ideology that has captured economics and economic policy.

Financial regulation that promotes shared prosperity

Quantitative monetary policy is a first cousin to regulation in that it adjusts the rules of the game in response to changing economic circumstances. In addition, systemic regulation is needed to limit the monopoly power of big finance and to ensure the efficiency and stability of the financial system. The Federal Reserve has always had an important regulatory role, and that role has been increased by the Dodd–Frank Act (2010).

In the wake of the financial crisis of 2008, the banking system has become even more concentrated and dominated by the top 10 banks. That means there is a permanent role for lobbying the Federal Reserve to ensure that it promotes and enforces regulations friendly to workers and families, and that it combats monopoly tendencies in banking. The Fed also needs to limit “too-big-to-fail” risks and subsidies that come from large banks being so big they know they can take extra risk because they will always be bailed out. Lastly, the Dodd–Frank Act established new laws limiting speculative activity by banks and requiring that banks support their activities with appropriate levels of capital. However, making real on these laws requires tough regulatory rule-writing by regulators, including the Federal Reserve.

The Fed and exchange rate policy

Exchange rate policy is another area where change is needed. The rate at which the dollar exchanges for foreign currencies is one of the most important economic variables. It impacts the international competitiveness of U.S. industry, which in turn affects the trade deficit, manufacturing employment, and corporate decisions about whether to invest in the United States or offshore. The Fed’s policies have an enormous impact on the exchange rate. For instance, higher interest rates make the dollar relatively more attractive to investors, which can appreciate the exchange rate. In this fashion, the Fed affects the trade deficit and the health of manufacturing.

Exchange rate policy is formally under the jurisdiction of the Treasury. That standing has been used to deflect engagement with the Fed on this critical issue, despite the fact that the Treasury uses the Fed to implement exchange rate policy. Moreover, the Fed has to take account of the exchange rate in its policy deliberations since exchange rates have such a huge impact on the economy and the Fed’s decisionmaking environment.

From the standpoint of working families, for the last 20 years the Treasury has done an awful job with exchange rate policy. That has been even truer under Democratic administrations. This policy failure reflects the fact that the Treasury is totally captured by Wall Street and big business. Consequently, it has been willing to accept (and even promote) an overvalued dollar because Wall Street and big business both profit from offshoring investment and outsourcing. However, working families cannot move to protect themselves, and they suffer the consequences of job loss caused by an overvalued dollar.

It is time to expose the Kabuki theatre that allows the pretense that the Fed, the Treasury, and exchange rates are unconnected. Exchange rates and interest rates are joined at the hip, and policy should be properly coordinated. In light of the failure of exchange rate policy, Congress should consider stripping the Treasury of its exchange rate responsibility and moving that responsibility to the Fed with accompanying strict congressional accountability rules.

In the meantime, exchange rate concerns should be raised with the Fed by asking how the Fed factors the exchange rate into its interest rate setting, and how it takes account of the impact of interest rates on the exchange rate.

The Fed, budget deficits, and Social Security solvency

The Fed’s effect on exchange rates is one unspoken feature of Fed policy. Another is the Fed’s effect on the budget deficit and Social Security solvency. The Fed adversely affects the budget deficit in two ways. First, higher interest rates reduce employment, which in turn reduces tax revenues and increases the budget deficit.7 Second, higher interest rates increase interest payment obligations on the national debt. Thus, a major contributor to the increase in the national debt in the 1980s was the high interest rate policy implemented by then–Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker. Third, higher interest payment obligations pre-commit budget revenues, creating budget deficit problems that are then politically exploited to attack government as irresponsible and also to justify cutting spending that benefits working families. These fiscal effects provide further reason for keeping interest rates low.

The economist Dean Baker (2014) has also argued higher interest rates undermine the solvency of Social Security. That is because Social Security is funded via payroll tax revenues on which higher interest rates have two negative impacts. First, higher interest rates lower employment. Second, lower employment lowers wages. The net result is payrolls are smaller, meaning less payroll tax revenue for Social Security.

This impact on the federal budget and Social Security, via interest rates, reveals yet another side to the importance of the Federal Reserve. It also provides another clear reason why Congress should be concerned about the Federal Reserve.

Reverse the biased use of the Fed’s bully pulpit

A final area where change is needed concerns the biased use of the Fed’s bully pulpit. In addition to setting monetary policy and regulating the financial system, the Fed has enormous influence on overall economic policy by shaping and coordinating elite economic policy understanding and opinion. This influence works through the Federal Reserve’s enormous research activities, high-profile economic conferences and publications, communications with the business community and media, and policy speeches given by the Federal Reserve chairperson and board of governors. These activities shape and legitimize understandings of the economy that in turn drive policy. For the last 30 years, the Fed’s bully pulpit has been enlisted to serve the neoliberal economic policy agenda. It is time to challenge and reverse that.

Institutional architecture

The previous sections have explored why the Federal Reserve is so important, and why and how its policy framework and tools should change. This last section describes the institutional architecture of the Federal Reserve, an understanding of which can help guide policy engagement.

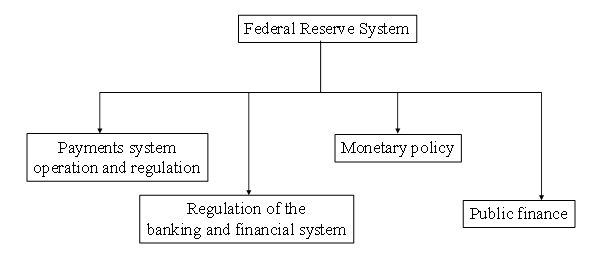

The Federal Reserve was created in 1913 by the Federal Reserve Act. Its original purpose was to ensure the soundness and stability of the banking system, thereby contributing to overall economic stability and helping the country to avoid financial crises. In many ways, that remains its preeminent purpose, but its functions have also evolved and expanded to include a) the conduct of monetary policy that includes management of interest rates, b) regulation of both the banking system and the broader financial system, c) management of the payments system, and d) serving as the government’s fiscal agent and banker. These functions lie at the base of the Fed’s enormous economic power.8

Political architecture

The Federal Reserve is a unique hybrid institution. It is unlike central banks in other countries which are government owned and controlled. Instead, reflecting the political characteristics of 1913, it is a hybrid structure that embeds private versus public interests, and regional versus national interests.

Formally, little of that architecture has changed since 1913. However, in practice, power has shifted away from private/regional interests toward the public/national interest. That said, private/regional interests remain strong, which means the Federal Reserve is not a level playing field, and policy input and deliberations are biased in favor of selective private interests.

One day, it may be possible to modernize the Federal Reserve’s architecture and bring it up to a level consonant with the ideals of a modern 21st century democracy. However, at the moment that is not a realistic political objective (as those powerful private interests would be against reform), and the American public is not sufficiently knowledgeable or unified about the problem and its solution. Instead, for the time being, effort is best directed at influencing Federal Reserve monetary and regulatory policy and strengthening working family–friendly representation within the Fed.

Geographic architecture

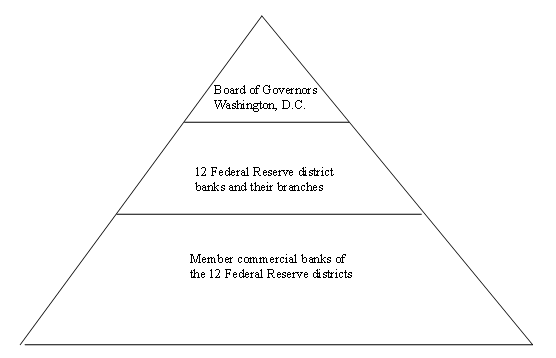

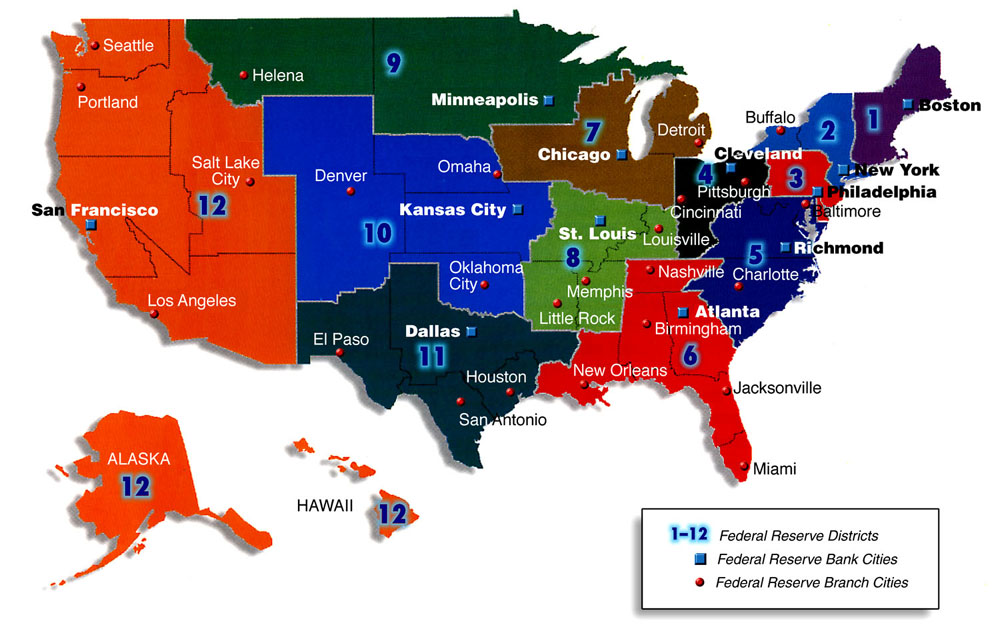

Just as the U.S. Senate was designed to represent regional interests, so too was the Federal Reserve. The Board of Governors in Washington, D.C., constitutes the Federal Reserve’s headquarters and its most important and powerful component. The rest of the country is divided into 12 geographic districts, each of which has its own Federal Reserve bank. There are also subsidiary Federal Reserve branch banks within the districts that report to the Federal Reserve district bank. Private commercial banks within each district can become members of the Federal Reserve by acquiring a federal banking charter and buying an ownership share in their district Federal Reserve Bank. This core structure is illustrated in Figure B.

The structure of regional interests is shown in Figure C, and Table 1 provides further details about the district bank–branch structure. New York is preeminent among the 12 district banks because financial markets are centered there, and the trading desk at the New York bank implements the monetary policy instructions (i.e., managing interest rates via buying and selling financial paper) that come from the Board of Governors in Washington, D.C. Inspection of the map in Figure C shows the Federal Reserve’s geographical architecture matches the structure of the late 19th century railroad economy. District banks are concentrated in the Northeast, which was the most industrialized and most densely populated part of the country at that time. The 12th district bank (San Francisco) covers an enormous chunk of territory because the West at that time was undeveloped and sparsely populated.

An important historical role of the branch banks was to quickly deliver supplies of cash. Geographically large districts, like the 12th, therefore have several branches. This framework is clearly antiquated; there is no need for it given current monetary and economic information gathering technology. The system could easily be modernized by closing both district banks and branches without any efficiency loss. However, the politics of closure would be similar to closure of military bases. District banks and branches have strong regional political defenders who want to retain the prestige, the voice, and the jobs that go with having a Federal Reserve presence.

With regard to directly engaging the Federal Reserve, this can be done at three levels with different impacts. The highest level of engagement is with the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve in Washington, D.C. The next level of engagement is with the 12 district banks. This is important because they provide input to policy formation in Washington, D.C. Below that, there is engagement with the branch banks, which provide the district banks with local economic information and communicate policy concerns and recommendations. Additionally, Congress has overall oversight of the Federal Reserve via hearings in the Senate and the House, so there is a role for engagement with Congress. There is also a role for engagement with the administration, which appoints the Board of Governors (about which more below), and the administration also has the Treasury Department conduct regular policy conversations with the Federal Reserve.

Ownership and control architecture

Whereas the Fed’s geographic architecture reflects the balance between regional and national interests, its ownership and control architecture reflects the balance between private and public interests. The ownership architecture has member commercial banks of each district owning 100 percent of the paid-up capital of each district bank, on which they receive 6 percent interest per year. Profits earned by the Federal Reserve, after payment of interest to member banks, are paid to the U.S. Treasury. This ownership structure gives private banks significant control rights over the Federal Reserve district banks. It also provides private banks with an avenue of policy influence.

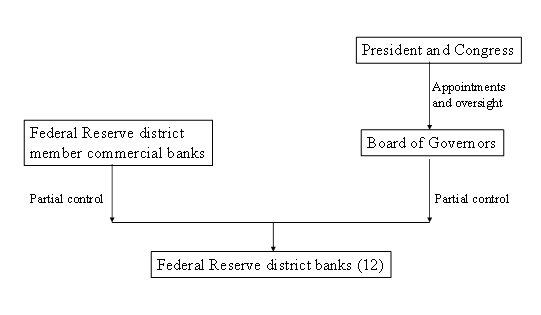

Figure D provides a simplified description of the Federal Reserve’s control structure and shows how it incorporates both private and public interests. The private interest operates through the member commercial banks, which are the stock owners of the Federal Reserve district banks. The members have significant partial control over the district banks, which gives them power to influence the policy deliberations and actions of the district bank, and thereby influence the Federal Reserve’s policies. The public interest operates through the Board of Governors, which also has partial control over the Federal Reserve district banks, and the Board of Governors is in turn subject to controls by Congress and the president.

The seven members of the Board of Governors (BOG) are appointed by the president, subject to confirmation by the Senate. The chair is the most important figure, having great convening and agenda-setting power and also being the tie-breaker vote. The Fed’s governance culture is also one of consensus, which means the impulse is to support the chair unless disagreement is significant. This consensus culture is very important and provides a channel for district banks to exert major policy influence (about which more later).

The chair’s appointment is for four years, while the other governors are appointed for 14-year terms that are sequenced so that every two years one governor is up for reappointment. If a governorship becomes open mid-term, replacements are appointed to serve the remainder of the term. Lobbying the administration and the Senate regarding appointment of suitable governors is a critical channel for influencing the Fed.

Additionally, the Federal Reserve is answerable to the Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act (1978), also known as the Humphrey–Hawkins Act, which requires the Fed to strive for full employment, growth in production, price stability, and balance of trade and budget. In practice, attention focuses on the employment and price stability mandates, especially since the balance of trade and budget are much more under the control of the Treasury. As part of that mandate, the Fed chair gives biannual testimony to the House and Senate in Humphrey–Hawkins hearings. Those hearings put the Fed in the public spotlight and, working with the appropriate congressional committee members, provide another opportunity to influence Fed policy and to shape the national economic policy conversation.

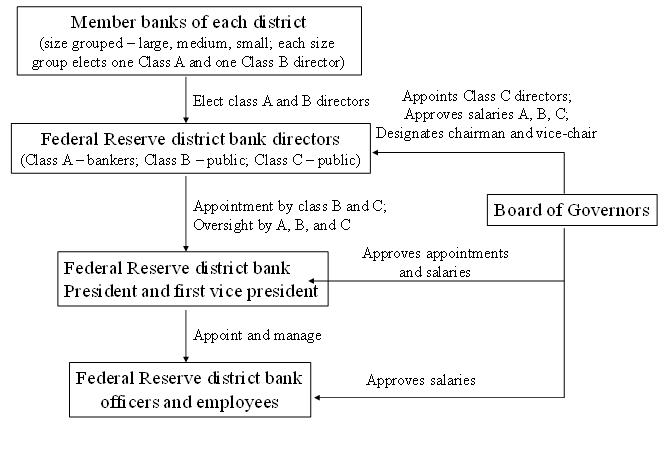

Figure E provides a detailed description of the control architecture of the Federal Reserve district banks, which are under the combined control of their shareholders (member commercial banks) and the Board of Governors (BOG). Each district bank has a hybrid private–public corporate structure. As the shareholders, member commercial banks have control rights; as representative of the public interest, the BOG also has control rights.

Figure E describes the main control structure, but a few additional comments are in order. First, member commercial banks directly exercise their influence over Federal Reserve district banks via election of the three Class A and three Class B directors for each district bank: Class A directors are drawn from the banking community, while Class B directors are drawn from the wider business and nonprofit community. Second, as a result of reforms under the Dodd–Frank Act of 2010, only Class B and C directors participate in the selection of district bank president, but all three classes of directors participate in oversight of the district banks. The Dodd–Frank restriction was introduced because district bank presidents are closely engaged in monetary policy, and having Class A director involvement in the selection process would raise conflict-of-interest concerns. Third, the BOG has power over each district bank via its appointment of three Class C directors and via its designation of which directors serve as chair and vice-chair of the district bank’s board. It also has power via the requirement that it approve persons selected by the district bank’s B and C directors to be president and first vice-president.9

Working-family advocates can have an influence on district banks by lobbying the BOG to appoint suitable Class C directors and an appropriate chair and vice-chair for the district bank’s Board of Directors. Class C directors are intended to represent the general public and labor unions. There are restrictions on who can serve as a district bank director, and there are also political activity restrictions on bank directors.

Influencing the selection of district bank presidents is important for several reasons. First, as discussed below, district bank presidents provide direct and important input into the Federal Reserve’s monetary and regulatory policy. Second, district bank presidents have their own significant bully pulpit that has both regional and national reach. Speeches by district bank presidents get significant attention in both regional and national media, which enables them to influence the national policy debate. Third, the district Federal Reserve banks are significant sponsors of economic research that influences policy debate and economic understanding, and the character of that research is influenced by who controls the district banks. In this regard, the district banks employ large staffs of professional economists who influence economics and the economic policy debate via their research activities. Subsequently, staff may use the status acquired by working for the Federal Reserve to move to important positions in business, the academy, the think-tank world, and government. The district banks also hire academics on sabbatical and sponsor policy conferences, such as the world-famous annual Jackson Hole conference sponsored by the Kansas City Federal Reserve. These activities promote and legitimize particular policy perspectives, while delegitimizing and obstructing others.

Functions and policymaking architecture

The previous sections have described the geographic and ownership and control architecture of the Federal Reserve. That architecture is important for understanding how the system works, the sources of influence within the system, and how to engage the system. This section turns to the policymaking architecture, with a focus on regulation and monetary policy. Figure F shows the Federal Reserve’s major functions.

The payments system

The first major function in Figure F is the management and supervision of the payments system, which is an essential piece of financial infrastructure. The 12 district banks provide banking services to depository institutions and the federal government. For the depository institutions, including those that are not members of the Federal Reserve, the district banks maintain accounts for reserve and clearing balances and provide various payment services, including collecting checks, electronically transferring funds, and distributing and receiving currency and coin. Users are charged a fee for provision of these services that covers the cost of provision.

Under the supervision of the Board of Governors, the 12 district banks operate two key payment and settlement systems, the Fedwire Funds Service and the Fedwire Securities Service. Additionally, the Federal Reserve is the prudential supervisor of the major privately organized payment, clearing, and settlement arrangements.

Regulation

Ensuring a sound and stable payments system requires that the system’s participants be financially sound and stable. That connects to the Federal Reserve’s second major function: regulation aimed at ensuring the stability and soundness of the banking and financial system.

Much regulation is the product of congressional legislation, and the Federal Reserve plays an important role in shaping regulatory legislation. However, even more important is its role in implementing regulatory legislation. That implementation role introduces enormous discretion in terms of writing regulatory rules, standard setting, and enforcement action. Furthermore, in the wake of the financial crisis and the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (2010) that it spawned, regulation has become even more important, and the Federal Reserve’s role and powers as financial regulator have increased.

Given the enormous impact and significance of regulation and the regulatory role of the Fed, it is vital that working-family interests are represented in regulatory deliberations. That is a difficult task owing to the technical nature of the issues. It can be done by lobbying with regard to specific regulatory issues, and by ensuring appointment of appropriate people (governors and Class C directors) within the Federal Reserve. Such appointments can create space for representation of different points of view. They can also help counter the proclivity for the regulatory process to be captured by those who are supposed to be regulated (i.e., for banks to gain undue influence within the Federal Reserve).

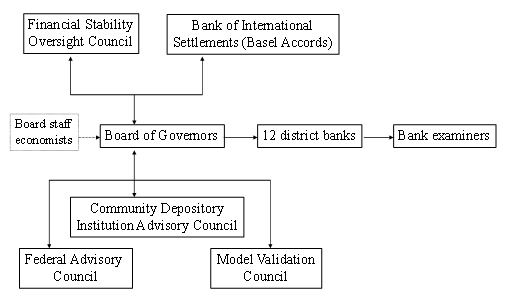

Figure G provides a schematic outline of the architecture of the Federal Reserve’s regulatory apparatus. The Board of Governors is responsible for regulatory policy, and regulation is overseen via bank examiners employed by the 12 district banks. The Board of Governors is advised by the Federal Advisory Council (FAC), the Community Depository Institutions Advisory Council (CDIAC), and the Model Validation Council (MVC). The FAC is a statutory body and consists of 12 private-sector bankers, drawn from the 12 districts and each nominated by the respective district bank. The CDIAC is a non-statutory body that was established in 2010 and advises the Board regarding concerns of community depository institutions. The MVC was established in 2012 and advises regarding the effectiveness of technical models used in financial stress testing of banks.

The Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) is a consultative body established by the Dodd–Frank Act and chaired by the Treasury secretary. The chair of the Federal Reserve is a member of the council, and the council’s purpose is to coordinate regulatory activities and duties across different regulatory agencies. These different agencies include the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), the Federal Housing Finance Authority (FHFA), the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA), and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). All are represented on the FSOC.

The Federal Reserve also has regulatory obligations and requirements established through international agreements, such as the Basel Accords, that are coordinated through the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) based in Basel, Switzerland. These international regulations are becoming increasingly important owing to globalization of financial markets that links U.S. and foreign financial markets. In this new environment, the stability and soundness of the domestic financial system increasingly depends on the stability and soundness of foreign financial systems. That increases the need for international accords on financial regulation.

Lastly, an invisible channel of influence comes from the advice of staff economists to the Board of Governors. Policy advice given depends on one’s belief. For the past 30 years, the economics profession has drifted against regulation and in favor of so-called free markets. That intellectual drift, often characterized as a shift to “neoliberalism,” has undoubtedly impacted the thinking of the staff and has thereby impacted the Fed’s regulatory stance and actions.

The effects of regulatory capture and intellectual drift are evident in the history of consumer financial protection. Previously, the Federal Reserve had considerable responsibility for such protection, and the Board of Governors used to be advised by a Consumer Advisory Council that was shuttered in 2011. Those consumer protection duties were stripped away by the Dodd–Frank Act and relocated in the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. The reason was that Congress thought the Fed had not paid adequate heed to consumer issues prior to the crisis, thereby contributing to the subprime mortgage crisis. The reason for this lack of heed seems to have been a combination of regulatory capture plus relative disinterest by the staff, who were more concerned with other high-profile policy issues, particularly monetary policy. That history of neglect speaks again to the need for working-family representation to counter regulatory capture and intellectual bias within the Fed.

Monetary policy

Monetary policy refers to actions undertaken by the Federal Reserve to influence the availability and cost of finance to promote national economic goals such as employment, economic growth, and control of inflation. Broadly speaking, monetary policy works by setting the interest rate that banks must pay for short-term finance. That interest rate is at the base of the financial system, and it in turn influences asset prices and the price of credit to the rest of the economy, which influences the general level of economic activity and employment.

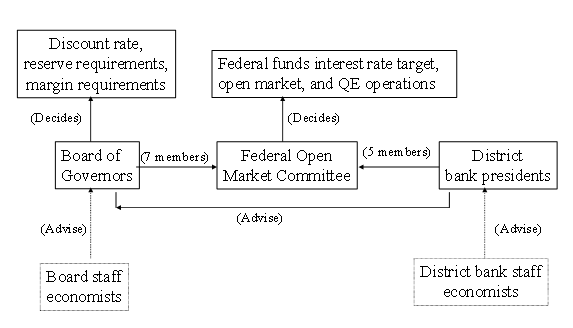

The main instruments of monetary policy are the discount rate, reserve requirements, margin requirements, the federal funds interest rate target, and open market and quantitative easing (QE) operations.10 The discount rate is the interest rate at which the Federal Reserve lends liquidity (reserves) to member commercial banks. Reserve requirements are reserves that banks must hold against demand deposits (i.e., checking accounts). The technical operation of these instruments of monetary policy is not of concern for this guide. What is important is who decides how those instruments are deployed and in whose interest are they deployed.

Figure H shows the schematic architecture of monetary policy decisionmaking. It helps shed light on several important aspects of monetary policy decisionmaking, particularly regarding sources of systemic policy bias. First, interest rate policy is set by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), which consists of 12 members: the seven members of the Board of Governors plus five district bank presidents. The New York Federal Reserve Bank president has a permanent seat; the presidents of the Chicago and Cleveland Federal Reserve banks also have a seat that alternates annually between them; and the remaining three seats rotate annually among the other nine banks, which are divided into three groups of three. However, even though the formal voting power of the district bank presidents is limited, all 12 district bank presidents participate in FOMC meetings and have “voice.” This enables them to influence interest rate policy. Moreover, that influence is formidable because the Federal Reserve prides itself on consensus decisionmaking. Since district bank presidents have historically been more pro-business and pro-finance (reflecting who elects them), this gives a meaningful invisible anti-working-family tilt to the process governing interest rate policy decisionmaking. This pro-finance, pro-business attitude shows up in “hawkish” attitudes toward inflation.

Second, over the last three decades, the focus of monetary policy has shifted almost exclusively to managing interest rates, and quantitative monetary policy (reserve and margin requirements) has been essentially abandoned. That shift reflects the adverse impact of changed thinking among economists, who have discarded these valuable policy tools. As discussed earlier, reversing that policy shift is a major challenge.

Third, economists play a very significant role in making monetary policy via the behind-the-scenes advice staff give the Board of Governors and the district bank presidents. Furthermore, the Federal Reserve chairperson, many governors, and many district bank presidents may be economists. Over the last three decades, the economics profession has become significantly more neoliberal in outlook. The combination of this drift and economists’ influence within the Federal Reserve has contributed a significant anti-working-family taint to monetary policy. That impact is evident in beliefs that deny the impact of monetary policy on employment, economic growth, and wages; beliefs that heavily emphasize the dangers of and damage from inflation; and beliefs that deny the merits of quantitative monetary policy and the need for quantitative regulation to ensure financial stability.

Furthermore, as a group, neoliberal economists have exhibited strong proclivities to exclusionary groupthink. Activists have an essential role in combating such groupthink and ensuring that alternative economic points of view get a hearing within the Federal Reserve’s policymaking process. Even if they are not economists themselves, activists can promote pluralist economic policy thinking by pushing the Federal Reserve to include and listen to different points of view.

Public finance and the Fed

A fourth important function of the Federal Reserve concerns public finance and the Fed’s role as fiscal agent for the federal government. In effect, the Fed is the government’s banker, and tax revenues are paid into the Treasury’s account that is maintained with the Federal Reserve. The Treasury also makes payments that are drawn against that account.

This special relationship between the federal government and the Fed gives a unique degree of financial freedom to the federal government that is not available to ordinary households. Given congressional budget authorization, if the federal government writes a check the Federal Reserve can, in principle, issue money to cover the check. That facility is not available to ordinary households, and it is one reason why the federal government is not like ordinary households, despite frequently asserted and mistaken claims that both are bound by the same budget arithmetic.11

Historically, the Federal Reserve has used its power to create money to help finance the federal government. It has done so by buying government bonds. Such purchases also lower longer-term market interest rates which are, in part, priced off of the interest rate on government bonds. Expanding this public finance role of the Fed is an important way in which the Fed’s power can be harnessed to promote shared prosperity.

During the Great Recession the Fed expanded the reach of its financing activities to include the housing sector via purchases of mortgage-backed securities issued by the Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA, or Fannie Mae). This use of the Fed’s financing power to bring down the cost of housing finance should now become a permanent standalone aspect of Federal Reserve policy.

Furthermore, the Fed should assist with the financing of public infrastructure investment. This would raise growth by relaxing the financing constraint that currently unduly restricts such investment. The Fed appears to have statutory authority to assist with state and local government financing, but it has not acted on this for a combination of political reasons and lack of suitable intervention mechanisms. One possibility for remedying this is creating a national infrastructure bank whose bonds the Fed could purchase. A second possibility is that a new federal agency, similar to Fannie Mae, could be created to securitize state and local government infrastructure bonds, and the Fed could then buy those securitized bonds.

Conclusion: Shared prosperity is doubtful without the Fed

The Federal Reserve’s policies affect almost every important aspect of the economy. As such, it is doubtful we can achieve shared prosperity without the policy cooperation of the Fed. This makes activist engagement with the Fed and its policies a matter of the highest importance.

In the wake of the Great Recession, monetary policy focused on quantitative easing. Now, there is talk of normalizing monetary policy and interest rates. That conversation is important, but it is also too narrow and keeps policy locked into a failed status quo. There is need for a larger conversation regarding the entire framework for monetary policy and how central banks can contribute to shared prosperity.

The Fed suffers from an anti-working-family bias. That bias reflects both the specific hardwired institutional characteristics of the Fed and the political characteristics of the time. With regard to institutional characteristics, the Fed’s legal setup means it is significantly influenced by the banking industry, and it is also prone to regulatory capture by the banks it is supposed to regulate. With regard to the politics of the time, the neoliberal capture of the economics profession and society’s understanding of the economy imparts an intellectual bias to the views of policymakers and the advice of the Federal Reserve’s economic staff. The combination of the importance of Fed policy and institutionalized bias makes countervailing activist engagement with the Fed a critical necessity.

— This paper represents the views of the author and not those of the AFL-CIO. The author thanks Ron Blackwell for his especially helpful comments about the significance of full employment, and also thanks Jane D’Arista and Tom Schlesinger for their helpful comments. The author takes full responsibility for any errors or inaccuracies.

About the author