Executive summary

Scholars have long recognized that the workplace is not just where workers carry out their jobs. It is also a place where individuals can learn and exercise civic skills and move to political action. While the political potential of the workplace is well understood, we know much less about how the shifting terrain of power between workers and employers has changed civic opportunities for workers. This paper examines the contemporary landscape of civic engagement in the workplace, focusing on two changes to worker economic power—declining unionization and changing employer and worker labor market power—to investigate whether greater employer clout has affected civic opportunities for U.S. workers in the workplace.

Results from an original, nationally representative survey of over 1,200 employed U.S. workers from the pre-Covid period reveals several important facts about civic engagement in the workplace:

- In an era of intense political polarization and division, the workplace remains an important site for workers to interact with others who do not necessarily share their own political stands. Most workers do not pick their workplace on the basis of the political views of coworkers or managers, and over 60% of workers work alongside coworkers who do not share their political affiliations.

- The workplace additionally remains an important site for workers to learn and practice civically relevant skills (like working with others on teams or public speaking), to engage in political discussions, and to receive requests for political participation. Indeed, the workplace offers the most common social network for political discussions after friends and family members. Just as importantly, the workplace is also more egalitarian in its civic opportunities, with smaller inequalities across income and education than in other areas of life.

- Yet not all workers enjoy these civic benefits of the workplace, and nonunionized workers and workers who report lower levels of bargaining power relative to their managers are less likely to say that they have opportunities for political skill-building, political discussions, and civic engagement at their jobs.

- For instance, 58% of union members say that they have been engaged in politics at work by coworkers—for example, by having a coworker ask them to support a political cause, candidate or campaign; remind them to vote; or inform them about a new political issue—compared with just 36% of nonunion workers.

In another example, 28% of workers who say that they could find a comparable job to the one they currently hold report discussing politics or political issues with coworkers at least once a week, compared with only 16% of workers who said it would be very difficult to find a new comparable position.

This paper also considers whether workers who have lost economic standing in the workplace have found alternative sites for political discussions outside of their jobs. The findings suggest that the answer is no. In fact, union members and workers with greater labor market power were more likely to say that they had political discussions outside of work than were nonunion workers or less economically secure workers. This suggests that the loss of workplace political engagement has not been offset by greater political engagement elsewhere in workers’ lives—and if anything, erosion of worker power may have knock-on effects for political engagement outside of the workplace.

The findings in this paper thus suggest that changes in workplace power over the past several decades have not just reshaped economic conditions, like pay, working conditions, and inequality. These changes may have also seeped into the political system, corroding opportunities for political skill building and civic participation for millions of American workers—and disproportionately those with less formal education and lower incomes who have fewer chances to engage in politics outside of the workplace. Without other places to build civic skills, engage in political discussions, or learn about opportunities to participate in politics, many American workers may have less political voice—and representation in government—as a result of declining workplace power. Weaker workplace voice has left us with a weaker democracy.

Although these findings come from a pre-Covid-19 survey, they shed important light on the potential consequences of the crisis. This analysis suggests that the crisis will likely undermine civic opportunities in the workplace, especially for already marginalized workers, including low-wage workers, those with less formal education, and racial and ethnic minorities. The implication for policymakers is that a sustained response to manage the pandemic and support the labor market is justified on civic grounds, in addition to health and economic ones.

In addition, the results presented in this brief suggest that policymakers should be prioritizing Covid-19 responses that make it easier for workers to form and join labor organizations. As we will see, across outcomes, union members are consistently more likely to build and use civic skills in the workplace than are nonunion workers—and the union difference tends to be largest for workers with lower levels of formal education, helping to equalize civic skills across the workforce. A Covid-19 response that centers on labor organizing could thus help rebuild workers’ economic and civic standing.

Introduction

As millions of Americans found themselves out of work or working remotely from home for extended periods during the Covid-19 pandemic, the sudden break from normal employment routines underscored just how central work is in our society. Work provides the primary economic support for most Americans, with wages and salaries accounting for three-quarters of middle-class incomes (Mishel et al. 2012, chapter 2). In the distinctively American welfare state, employment also represents most families’ primary source of health and retirement security (Hacker 2002; Klein 2006). And, on a deeper level, work structures the rhythms, meaning, and connections present in our daily lives. Employed Americans regularly spend most of their waking hours outside of their homes at their jobs.1 Half of all workers say they draw a strong sense of identity and meaning from their jobs.2 And about three-quarters of workers report that they have at least one close friend from work.3 It is hard to think of another place in which we spend as much time, on which we rely for economic well-being, in which we derive self-meaning, and through which we are exposed to as many diverse individuals.

For all these reasons, it should come as no surprise that past research has documented a strong connection between workers’ civic lives and their jobs, describing the workplace as a “training ground for pro-democratic attitudes and political behaviors” (Budd, Lamare, and Timming 2018; see also Dahl 1986; Greenberg 1986; Greenberg, Grunberg, and Daniel 1996; Kitschelt and Rehm 2014; Pateman 1970). On a basic level, work provides financial resources individuals need to participate in many political acts (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady 1995). But beyond money, the skills that workers use at their jobs may also make it easier to participate in civic action in a variety of ways. Learning how to work in teams, manage others, speak publicly, interact with diverse individuals, and fundraise are all job-related skills that workers can use off the clock in political organizations or campaigns (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady 1995, especially chapters 10, 11, and 13). And more fundamentally, when workers exercise voice and input on the job, scholars argue, workers should gain a greater interest in doing so outside of the workplace in politics (see especially Greenberg 1986). Recognizing and challenging hierarchies of power in the workplace, for instance, might lead workers to do so outside of their jobs.

It is not just individual participation that might change through work. While on the job, many individuals also have an opportunity to meet a politically diverse network of coworkers (Conover, Searing, and Crewe 2002; Estlund 2003; Mondak and Mutz 2001; Mutz and Mondak 2006). That opportunity arises because unlike other places where we spend time—like churches or clubs—most workers do not choose where they work or with whom they work on the basis of political views (Estlund 2003; Hertel-Fernandez 2018). As a result, work offers a unique setting in which Americans can build ties to individuals with differing political outlooks and in the process build an understanding of—and tolerance to—opposing political views (Mutz and Mondak 2006; on labor views see Lyon 2018). Workplace political discussions can also move individuals to action outside of the job, as they learn about new issues, causes, or campaigns (Abrams, Iversen, and Soskice 2010; but see Adman 2008).

Lastly, work can be the site of political mobilization and recruitment by civic organizations situated around the workplace (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady 1995). Historically, these organizations have been part of the labor movement—like trade unions or worker centers (e.g. Fine 2006; Galvin 2019; Lichtenstein 2002). While they are often primarily focused on raising wages, benefits, and working standards, labor organizations also offer paths into politics for their members, conveying information about elections and issues and encouraging members to volunteer for campaigns, turn out to vote, contact elected officials, and even run for office (e.g. Bucci 2019; Feigenbaum, Hertel-Fernandez, and Williamson 2019; Kerrissey and Schofer 2013; Leighley and Nagler 2007; Rosenfeld 2014; Schlozman, Verba, and Brady 2012; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady 1995). On a deeper level, unions facilitate political action, both by serving as “schools of democracy,” where their members learn civic skills that they can apply in politics, and by changing the ways that members perceive their political and economic interests. These changes can include shaping how workers think about specific policies but also engendering a broader sense of community and solidarity (e.g. Ahlquist and Levi 2013; Frymer and Grumbach 2020; Hertel-Fernandez 2020a; Kim and Margalit 2017; Macdonald 2019; Mosimann and Pontusson 2017).

This much is known about politics in the workplace. But what is less well-known is how changes in the workplace have altered the political opportunities workers encounter on the job—and what that means for worker political voice more generally (Hertel-Fernandez 2020b). Many of the studies cited above draw on data from several decades ago. The ensuing years have seen a massive shift in the balance of market power between workers and employers driven by the erosion of policies and institutions that check employer behavior and boost the economic power of workers (Hacker and Pierson 2010; Stansbury and Summers 2020; Thelen 2015, 2019; Weil 2014).

As spelled out in more detail below, there are good reasons to think that these changes have eroded the political promise of the workplace—especially for Americans working in rank-and-file jobs. This paper begins to test that hypothesis, using an original survey fielded in November 2019 of 1,212 employed U.S. workers to study the connection between labor market developments and political skills, discussion, and mobilization on the job. More specifically, I focus on two components of changing power in the workplace: union membership and worker bargaining power relative to employers. I document how both factors are intimately linked to workers’ participation in politically relevant discussions, abilities to build politically relevant skills, and opportunities to engage in political mobilization of their coworkers.

These shifts in workplace power matter in different ways for workers’ political opportunities. I find that labor unions shape all three forms of workplace political voice that I study: Union members are more likely to report using politically relevant skills on the job, to say that they discuss politics with their coworkers, and to say that they have more political interactions with coworkers. Worker labor market power, on the other hand, mattered most for the political skills as well as the frequency of workplace political discussions—but not so much for political mobilization between coworkers.

I also consider whether workers who have lost economic standing in the workplace are finding alternative sites for political discussions outside of their jobs. I find that the answer is a resounding no. Nonunion workers and workers with less labor market power are no more likely to report alternative sources of political discussion beyond work. In fact, union members and workers with greater labor market power were more likely to say that they had political discussions outside of work than were nonunion workers or more insecure workers. This suggests that the loss of workplace political engagement has not been offset by greater political engagement elsewhere in workers’ lives—and, if anything, the erosion of worker power may have knock-on effects for political engagement outside of the workplace.

While far from the last word on these questions, my findings suggest that changes in workplace power over the past several decades have not just reshaped economic conditions, like pay, working conditions, and inequality. These changes may have also seeped into broader society, corroding opportunities for political skill building and participation for millions of American workers—disproportionately workers with less formal education and lower incomes who have fewer chances to engage in politics outside of the workplace (Schlozman, Verba, and Brady 2012). Without other places to build these civic skills, have political discussions, or learn about opportunities to participate in politics, many American workers may have less political voice—and representation in government—as a result of declining workplace power (Bartels 2008; Gilens 2012; Gilens and Page 2014; Hacker and Pierson 2010; Jacobs and Skocpol 2005).

This paper proceeds as follows. First, I describe the Workplace Political Participation Study, the survey I designed to study these questions in fall 2019. The following section uses results from that study to map out the contemporary landscape of political views and participation in the workplace, documenting that work still remains a site of political diversity and interaction for many workers, especially for workers with lower levels of formal education and lower incomes. Having laid out these descriptive facts, I then show how changes in economic power relate to workplace political skills, discussion, and mobilization. The final section concludes by summarizing the implications of this analysis for understanding the civic consequences of the Covid-19 crisis and the labor market policy responses that government ought to pursue.

The 2019 Workplace Political Participation Study

To provide an updated picture of political engagement at work, I designed and commissioned an original nationally representative survey of non-self-employed U.S. workers. The 2019 Workplace Political Participation Study (WPPS), conducted in November 2019 by YouGov Blue, consisted of 1,212 interviews from YouGov Blue’s internet panel selected to be representative of the adult general population and weighted according to gender, age, race, education, region, and past presidential vote (or nonvote) based on the American Community Study and the Current Population Survey Registration and Voting Supplement. The sample was then subsetted to look only at respondents who reported they were employed by someone else (i.e., not self-employed). The margin of error for the full sample is plus or minus 3.1%. All results presented below apply survey weights.

Despite the strengths of this survey—especially the fact that it targets an employed sample of interest and includes extensive items on workplace political participation—there are some important limits. First, the survey was administered in English, meaning that it does not reflect the experiences of non-English-speaking workers and especially immigrants. This is an important population, but one that I cannot study with the current sample. Second, the survey is a snapshot of workplace relations and political participation. Although I am fundamentally interested in trends in civic engagement, worker economic power, and union membership, this analysis can speak only to variation at the moment of the survey. Lastly, the survey was conducted before the Covid-19 pandemic, meaning that it does not reflect the current labor market. That said, there are important lessons we can learn from a pre-Covid study of workplace power and civic participation, lessons that offer predictions of how the crisis might change the picture of political interest and participation I describe below. The final section explores these predictions in greater detail.

The current political landscape in U.S. workplaces

Despite rising levels of political polarization—including increasing political “teamsmanship”—most workers do not choose their workplace on the basis of the political views of their coworkers or employer (but see Mason 2018). As a result, the vast majority of American workers are in workplaces where they regularly encounter coworkers and managers with different political beliefs from their own. What is more, the workplace remains a site where many workers from diverse backgrounds can build politically relevant skills, engage in political discussions, and learn about opportunities for political participation.

Political diversity at work

Many observers have bemoaned the perception that political life is becoming more insular—with partisans retreating into their own media bubbles, neighborhoods, stores, restaurants, and schools (e.g. Bishop 2008; Hetherington and Weiler 2018). Has the workplace followed suit as others have speculated (Chatterji and Toffel 2019; McConnell et al. 2018)? Several WPPS items probed the extent to which workers are sorting into their jobs on the basis of politics. The first asked workers, “How much of a consideration were the political views and positions of your employer or your coworkers when you were choosing where to work?” Options included “very important,” “important,” “slightly important,” and “not at all important.”

Over half of workers said that the political views of their coworkers and employer were “not at all important” as they were considering where to work: 56% for employers and 59% for coworkers. Twenty-two percent of workers said that their employers’ views were slightly important, and 21% said the same about coworkers; 22% said that employers’ views were very important or important, and 19% said the same about coworkers (Figure A) Union members and workers who reported following politics more closely were both more likely to say that coworker and employer politics were important to them, but even these differences were not very large. The lesson from this survey item is that, for most American workers, politics does not feature prominently in why they might choose a particular workplace.

Importance of political views of employer and coworkers for job choice: Share of respondents who say their coworkers' or employers' views are not at all to very important

| Views of coworkers | Views of employer | |

|---|---|---|

| Not at all important | 59% | 56% |

| Slightly important | 21 | 22 |

| Important | 12 | 15 |

| Very important | 7 | 7 |

Source: 2019 Workplace Political Participation Study. Sample size: 1,212.

Past research has indicated that this kind of involuntary association means that workers may be exposed to more individuals who might disagree with their political views (see especially Lyon 2018; Mondak and Mutz 2001; Mutz and Mondak 2006). To verify that this past finding still holds in our current era of polarization, I first asked workers if they were able to discern the political views of most of their coworkers or of their senior managers and supervisors. Thirty-eight percent of workers said that they did not know the views of most of their coworkers, and a higher share, 49%, said that they did not know the views of most of their senior managers and supervisors. (More highly educated workers and those in labor unions reported that they were more likely to know the views of both managers and coworkers.) These reports indicate that most workers have a good sense of how their coworkers think about politics and, while knowledge about senior managers’ views are less common, about half of all workers still have a sense of how the executives and supervisors in their organization might vote.

Of course, perceptions might not reflect reality. Workers could be incorrectly guessing the views of their coworkers and managers (on demographic misperceptions of who belongs to political parties, see e.g. Ahler and Sood 2018). Still, I am generally optimistic that workers will be mostly accurate in their estimates. First, past research has documented that individuals within specific companies and organizations tend to be accurate judges of their coworkers’ and managers’ political views (Hertel-Fernandez 2018; Mondak and Mutz 2001). Second, in the 2019 WPPS survey I found reassuringly that workers who reported more frequent discussions with their coworkers were more likely to say that they knew the views of those coworkers (Figure B). Also reassuring is that workers who reported longer tenures at their employer were substantially more likely to report knowing coworker and manager political views.4 This suggests that workers’ perceptions of the political leanings of their coworkers are rooted in reality. And lastly, political scientists have found that demographic characteristics and social activities—like church attendance, race, ethnicity, and education—are becoming increasingly predictive of partisanship, making it easier to potentially judge a coworker’s (or manager’s) partisanship even without extensive conversation (e.g. Mason 2018).

Workers not knowing coworkers' political views: Share of respondents reporting that they don't know political views of coworkers, by how they answered the question, "How often do you discuss politics, elections, or other political issues with people from work?"

| “How often do you discuss politics, elections, or other political issues with people from work?” | |

|---|---|

| Not applicable | 72% |

| Never | 63 |

| A few times per year or less | 31 |

| A few times per month | 20 |

| At least once a week | 12 |

Source: 2019 Workplace Political Participation Study. Sample size: 1,212.

Having established worker perceptions of the political views of their coworkers and managers, I next asked what those views were: “Would you say that they lean towards the views of Democrats, Republicans, or something else?” Responses included “mostly lean towards the views of Democrats,” “evenly divided between the views of Democrats and Republicans,” “mostly lean towards the views of Republicans,” and “don’t lean towards either Democrats or Republicans.” Thirty-eight percent of workers said that their coworkers were mostly Democrats, 28% thought that their workplace was evenly divided, another 28% thought that their coworkers leaned Republican, and 6% reported something else. By comparison, views about senior managers tilted Republican: 40% of workers reported that their senior managers leaned Republican, compared with 30% Democratic, 24% evenly divided, and 6% something else.

Using the responses to this item, I coded whether respondents worked in workplaces where their own partisan identification aligned with the majority of their coworkers and senior managers and supervisors. For instance, this measure captures whether a Democratic worker reported that most of his or her coworkers or managers and supervisors were also Democratic.

Far from the “big sort” of American life along partisan lines, feared by some, the workplace is still very politically diverse: Only 37% of workers reported being in a job where their partisanship lined up with a majority of their coworkers or managers, meaning that over 60% of workers are employed in jobs where they work alongside many individuals who do not share their partisan views. Political alignment is higher for Democrats and Republicans as compared with independents or third-party supporters (since there are very few workplaces where independents, third-party adherents, or nonadherents constitute a majority), but even so about half of partisans report being at a job where their party is not in the majority. What is more, nontrivial shares of workers report being in workplaces where they are in the political minority: 15% of Democrats and 18% of Republicans when looking at coworkers, and 30% of Democrats and 19% of Republicans when looking at senior managers and supervisors. Table 1 summarizes the distribution of workers by the political views of their coworkers.

Political diversity across U.S. workplaces: Share of respondents with given political views reporting perceived political makeup of their workplace

| Impressions of coworker political views | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent’s political views | Mostly Democrats | Evenly divided | Mostly Republicans | Neither party |

| Democrat | 21% | 10% | 6% | 2% |

| Republican | 5 | 8 | 14 | 3 |

| Independent/other | 11 | 10 | 8 | 2 |

Notes: Percentages as a share of all workers reporting that they know the view of their coworkers, N=787.

Source: 2019 Workplace Political Participation Study.

For the most part, there was not much variation across workers in whether they were in the partisan majority of coworkers at their jobs. Rather strikingly, the item asking whether workers chose their job based on the political views of their coworkers was only a modest predictor of workers’ alignment with coworker partisanship. So even though workers may say that they prefer a job working alongside Democrats or Republicans, they do not appear to have much control in practice.

The top panel of Figure C illustrates this relationship, showing the percentage of workers reporting partisan alignment with their coworkers depending on their responses to the item asking whether workers chose a job based on the views of their coworkers. The relationship is mostly flat, except for the workers who said that the political views of their coworkers were “very important.” Even among that group, however, over half still said that they were not in the partisan majority among their colleagues. The same is mostly true for workers’ choice of employers as well, graphed in the bottom panel of Figure C. Workers who said that they had the strongest preferences about their employers’ political views were more likely to report alignment, but the relationship is weak and inconsistent across the response categories.

Importance of politics in job choice and partisan alignment with coworkers and managers

: Share of respondents reporting partisan alignment with coworkers by how they answered the question, "How much of consideration were the political views and positions of your coworkers when you were choosing where to work?

| “How much of a consideration were the political views and positions of your coworkers when you were choosing where to work?” | Percent of respondents reporting partisan alignment with coworkers |

|---|---|

| Not at all important | 34% |

| Slightly important | 39% |

| Important | 39% |

| Very important | 45% |

: Share of respondents reporting partisan alignment with senior managers by how they answered the question, " How much of a consideration were the political views and positions of your employer when you were choosing where to work?"

| “How much of a consideration were the political views and positions of your employer when you were choosing where to work?” | Percent of respondents reporting partisan alignment with senior managers |

|---|---|

| Not at all important | 32% |

| Slightly important | 41% |

| Important | 36% |

| Very important | 47% |

Source: 2019 Workplace Political Participation Study. Sample size: 787 for coworkers; 636 for managers.

The 2019 WPPS indicates that we have strong reasons to think of the workplace as a site that continues to offer cross-cutting partisan exposure. Even when Americans would prefer otherwise, they tend to be working alongside coworkers and managers who do not share their political views and outlooks, underscoring the importance of the workplace as a site for “involuntary association” with a politically diverse set of individuals.

Use of politically relevant skills on the job

Past scholars have noted that the skills workers develop and use on the job, like talking to new people or running meetings, might be relevant for later civic action (see especially Verba, Schlozman, and Brady 1995). Drawing on this past work, I used the 2019 WPPS to probe how many workers regularly make use of skills that might translate into political activities. Because there are any number of skills that could be applicable in politics or civic action, I focus on those most relevant to organizational or associational involvements, as these offer some of the surest ways of developing political power, voice, and representation in American government (e.g. Hacker and Pierson 2010; Han 2014; Skocpol and Tervo 2020).

The 2019 WPPS asked respondents, “How often does your job require you to do the following?” and options included “at least once a week,” “a few times a month,” “a few times per year or less,” or “never.” The skills included “working closely with others on a team,” “public speaking,” “organizing and running meetings,” “convincing others of an argument,” “managing a team,” “delegating tasks or activities to others,” and “fundraising or asking people for money.” I make no claim that these are the only skills relevant for forming, running, and participating in political organizations (e.g. Andrews et al. 2010; Han 2014). Instead, they should be seen as a starting point for thinking about the translation of work skills into civic organizations.

Table 2 summarizes the responses to this question.5 There is wide variation both in the likelihood workers reported using any of these politically relevant skills and also in the frequency with which they reported using these skills. Most workers (nearly 90%) reported working closely with others on a team, indicating that this is how work is organized across many different industries and occupations. A large majority (nearly 70%) also reported some leadership activities, like delegating tasks or activities to others. Notably, this was true even for workers who said that they were not technically supervisors or managers; about half of rank-and-file workers reported that they still delegated tasks to others. About half of workers reported any experience with the next cluster of activities: managing a team, convincing others of an argument, and public speaking. The last activity—fundraising or asking people for money—is a mainstay of many civic and membership organizations, yet only about a quarter of workers said that they had experience doing this as part of their jobs.

Political skills used at work: Share of respondents reporting using political skills at work, by type of skill and frequency

| Political skills | Never | A few times per year or less | A few times a month | At least once a week |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Working closely with others on a team | 11% | 11% | 18% | 59% |

| Public speaking | 53 | 21 | 12 | 14 |

| Organizing and running meetings | 48 | 19 | 17 | 16 |

| Convincing others of an argument | 51 | 15 | 19 | 15 |

| Managing a team | 47 | 15 | 14 | 25 |

| Delegating tasks or activities to others | 34 | 16 | 19 | 30 |

| Fundraising | 76 | 13 | 7 | 5 |

Source: 2019 Workplace Political Participation Study. Sample size: 1,212.

Looking at the use of political skills across education, I find that workers with less formal education (especially a high school degree or less) are less likely than college-educated workers to report using all of these skills, but especially public speaking (Figure D). The smallest gap across educational degrees was for fundraising. Nevertheless, large percentages of workers with high school diplomas or less still reported using many of these skills: Nearly 80% of these workers said that they worked closely with others on a team, nearly 40% said that they organized and ran meetings or managed a team, and about half said that they delegated tasks to others.

Use of politically relevant skills, by education: Share of respondents who report ever using political skills, by type of skill and education level

| Percent of respondents reporting ever using skill | Ever, high school or less | Ever, some college | Ever, college or more |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working closely with others on a team | 79% | 87% | 96% |

| Public speaking | 29% | 35% | 68% |

| Organizing and running meetings | 36% | 39% | 71% |

| Convincing others of an argument | 30% | 41% | 67% |

| Managing a team | 40% | 46% | 68% |

| Delegating tasks or activities to others | 53% | 59% | 79% |

| Fundraising or asking people for money | 22% | 19% | 30% |

Source: 2019 Workplace Political Participation Study. Education sample sizes: High school or less, 344; some college, 354; college or more, 514.

Looking across income I found patterns similar to those across education: Higher-income workers were more likely to report using all of these skills, but even the lowest-income workers in the survey (with family incomes below $30,000) reported that they used many of these skills at least some of the time: About half had experience delegating tasks or activities to others, nearly 40% had experience managing a team, and nearly a third had experience with public speaking.

While I did not observe large racial or ethnic gaps in the use of political skills at work, there was a substantial gender gap, consistent with past research documenting persistent differences by gender in opportunities for careers that have knock-on effects for politics (e.g. Burns, Schlozman, and Verba 2001). Women were less likely to report all of these job skills with the exception of fundraising. The gap was especially large for managing teams (56% of women reported never doing this compared with 39% of men) or delegating tasks and activities to others (41% of women reported never doing this compared with 28% of men), consistent with gender differences in opportunities for managerial experience (Thomas et al. 2019). Even so, as with gaps by education and income, most women still reported using many of these politically relevant skills at their jobs.

Workplace political discussions

Apart from politically relevant skills, past research indicates that the workplace is an important site of political discussion—conversations about news, elections, and issues that can provide information, lend new perspectives, and motivate later action. How important is the workplace as a site for such conversations compared with other potential places in Americans’ lives? To tap into this question, the WPPS provided respondents the following prompt: “How often do you discuss politics, elections, or other political issues with individuals from the following parts of your life?” The options included “not applicable,” “never,” “a few times per year or less,” “a few times per month,” and “at least once a week.” The social networks included the workplace, family, friends, classmates, church or religious institution attendees, neighbors, union members, or members of civic or community groups (not unions). Table 3 summarizes the results of this item, and reveals several important facts.

Coworker political interactions: Share of respondents reporting engaging in political discussions, by source of discussion and frequency

| Sources of political discussions | Never/not applicable | A few times per year or less | A few times per month | At least once a week |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| People from work | 40% | 20% | 20% | 20% |

| Family | 21 | 18 | 24 | 38 |

| Friends | 22 | 24 | 26 | 28 |

| People from school | 82 | 6 | 7 | 5 |

| People from church | 73 | 12 | 9 | 6 |

| People from neighborhood | 60 | 19 | 13 | 7 |

| People from a union | 83 | 6 | 7 | 5 |

| People from civic groups | 73 | 11 | 9 | 7 |

Source: 2019 Workplace Political Participation Study. Sample size: 1,212.

First, a significant proportion of American workers—about a fifth—said that they never discussed politics with people from school, church, the neighborhood, or unions or civic groups or did so only a few times per year or less. Moreover, across all categories, well over half of workers in all cases (and sometimes much more) said that they were not having political conversations at least weekly. This is an important reminder that politics is not as central in most Americans’ lives as it is for many political advocates or observers (see e.g. Carpini and Keeter 1996). Second, family and friends emerge as the most frequent partners in political discussion (Conover, Searing, and Crewe 2002). Not only did most workers (around 80% in both cases) report that they had at least some political discussions with these groups, they tended to do so more often than with any other group listed on the survey. But apart from family and friends, people from work appeared as very important political conversation partners, far more than any other group for this national sample of workers. About a fifth of workers reported having political discussions with coworkers at least weekly, and another fifth reported having such discussions a few times per month. This item underscores that the workplace remains a very important place for seeding politically oriented conversations. (Indeed, this item may understate the importance of the workplace to the extent that people are meeting friends at their jobs and reporting those conversations under the “friends” category instead of work.)

Looking across levels of education, I identify very large gradients in the frequency and intensity of political discussions between workers with at least a college degree and those with only a high school degree or less. In all, nearly 40% of workers with a high school degree or less said that they either never had political discussions or only did so a few times per year or less, compared with just 16% of workers with at least a college degree. These educational differences were largest for political discussions among friends and families: Among those with a bachelor’s degree or more, 43% said that they had political discussions with their family at least once a week, while only 30% of workers with a high school degree or less said the same (Figure E). While there was an education gap for workplace-based political discussion, it was much smaller than those we saw for discussions between friends and family members: 22% of college-educated workers said that they had weekly political discussions with coworkers compared with 18% of workers with a high school degree or less.

Weekly political discussions, by education: Share of respondents who report engaging in weekly political discussions, by source of engagement and education level

| Percent of respondents reporting weekly political discussions | High school or less | Some college | College or more |

|---|---|---|---|

| People from work | 18% | 19% | 22% |

| Family | 30 | 38 | 43 |

| Friends | 24 | 26 | 33 |

Source: 2019 Workplace Political Participation Study. Education sample sizes: High school or less, 344; some college, 354; college or more, 514.

Differences across workers by family incomes were sharper than those by education. About 60% of workers with incomes below $30,000 said that they never had political discussions at work compared with about 25% of workers making $150,000 or more. Nevertheless, about a quarter of workers with incomes below $30,000 still said that they discussed politics at work at least monthly, and even for these low-income workers the workplace was the most common site of political discussions after friends and families.

Racial and ethnic differences in political discussions were not so straightforward. While white workers were more likely than Black or Hispanic workers to report political discussions with friends and family, there was barely any gap in the frequency of political conversations at work across racial or ethnic lines. And looking at the other sites of political discussion, I found that Black workers were substantially more likely than white workers to have political conversations with classmates, fellow churchgoers, union members, and community group members. (Hispanic workers fell somewhere in between white and Black workers.)

As with the previous item on politically relevant skills, I found gender differences in workplace political discussion as well: Women were both less likely to report having any political discussions with coworkers and, when they did report discussions, those conversations tended to happen less frequently then for their male counterparts. Nearly half of female workers said that they did not have any political discussions with their coworkers, compared with around a third of men. And while 23% of men reported weekly political discussions at work, only 16% of women reported the same.

Opportunities for political action at work

The final aspect of the workplace I consider are opportunities for political participation that workers might receive from their coworkers, which the literature suggests play an important role moving Americans into civic action (Rosenstone and Hansen 1993; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady 1995). To measure the prevalence of such opportunities, I asked respondents to the WPPS to indicate whether they had ever received a series of political requests from their coworkers. Table 4 summarizes the responses to the item, which asked respondents, “Thinking about your coworkers at your main job, have any of the following things ever happened to you? Please select all that apply.” The list included five political actions, ranging from those related to elections (like registering to vote) to how people think about politics, including discussing new issues or changing one’s mind about existing issues.

Coworker political interactions: Share of respondents who report interactions with coworkers, by type of interaction

| Political interaction | % of workers |

|---|---|

| Asked to support a political candidate, campaign, or issue | 12% |

| Asked to register to vote or to vote | 15 |

| Asked to attend a political event or meeting | 9 |

| Changed my mind about a political issue | 9 |

| Told me about a political issue I hadn’t thought about before | 22 |

| Nonpolitical interaction | |

| Asked to attend a nonpolitical event | 24 |

| Asked to volunteer for civic organization or charity | 11 |

| Any political interaction | 39 |

| Any non-political interaction | 28 |

Source: 2019 Workplace Political Participation Study. Sample size: 1,212.

In all, nearly two-fifths of workers said that they had ever had political interactions with their coworkers. The most common of these interactions included learning about new political issues, indicating that the workplace can be an important way that people find new politically relevant information. Less common were political requests around elections (at 15%); support for particular candidates, campaigns, or issues (at 12%); and changing one’s mind about an issue or attending a political meeting or event (both at 9%). The battery also included two nonpolitical coworker requests to better understand just how frequently coworkers had any interactions with one another involving causes or issues outside work. These two nonpolitical items included requests to attend a nonpolitical event (at 24%) and volunteer requests for a civic organization or charity (11%). Requests to support civic organizations and charities were roughly as common in workplaces as appeals to support political candidates, campaigns, or issues. (Of course, there may be overlap in these categories, as different respondents may have varying definitions of what counts as a charity, civic organization, or political campaign.) Invitations to attend nonpolitical events were even more common than requests to attend political ones.

The WPPS indicates that workplaces with more nonpolitical participation also tend to be those where coworkers receive more political requests and information from coworkers, too. Workers who said that they had been asked to attend nonpolitical events and volunteer for civic organizations or charities were more than two-and-a-half times more likely to say that they had also received at least one political request from their coworkers. This suggests that some workplaces are simply more oriented toward sharing information and invitations to outside events and organizations than others.

As with the past two types of workplace political items, there was also a sharp educational gradient to coworker political opportunities, with workers with higher levels of formal education more likely to report all forms of coworker political interactions (Table 5). Even so, nearly a third (30%) of workers with a high school degree or less reported at least one political interaction with their coworkers, compared with 44% of workers with at least a college degree. Not all political actions were divided along degree lines, however. Workers with a bachelor’s degree or more were substantially more likely to report being asked to attend political events and meetings. But there were only small differences by education in whether workers reported learning about new political issues from their coworkers (19% for workers with a high school diploma or less versus 25% for workers with a bachelor’s or more) and changing one’s mind about an issue after talking with a coworker (7% for workers with a high school degree or less compared with 11% for workers with a bachelor’s or more).

Coworker political interactions, by education: Share of respondents who report interactions with coworkers, by type of interaction and education level

| Political interactions | High school or less | Some college | College or more |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asked to support a political candidate, campaign, or issue | 8% | 12% | 14% |

| Asked to register to vote or to vote | 10 | 17 | 18 |

| Asked to attend a political event or meeting | 4 | 9 | 13 |

| Changed my mind about a political issue | 7 | 9 | 11 |

| Told me about a political issue I hadn’t thought about | 19 | 21 | 25 |

| Nonpolitical interactions | |||

| Asked to attend a nonpolitical event | 13 | 21 | 34 |

| Asked to volunteer for civic organization or charity | 4 | 9 | 17 |

| Any political action | 30 | 40 | 44 |

Source: 2019 Workplace Political Participation Study. Sample size: 1,212.

Changes in employer power—and consequences for worker political voice

Having laid out the landscape of civic engagement in the workplace, I next probe how two changes to the workplace may have shifted the economic power employers have relative to workers and their corresponding consequences for workplace political participation. Using the WPPS, I capture these changes in the following ways, recognizing that while I am studying long-term developments in the labor market, the WPPS survey data are available only for a single, pre-Covid-19 snapshot in time in fall 2019.

Decline of labor unions

I measure this change with a binary indicator for whether WPPS respondents reported that they were in a labor union. A little over 10% of workers reported union membership in the survey. Union membership rates were highest in education and public administration in the public sector and in mining, oil and gas extraction, utilities, and trade and transportation in the private sector. I expect that the decline of labor unions—a key driver of declining worker power in the workplace—will remove a crucial source of political information, socialization, and mobilization for workers. With unions disappearing from the labor force, we should thus expect lower levels of political engagement, discussion, and participation among workers. That includes engagement around elections as well as in the policy process.

Beyond their direct effects, I anticipate unions will also matter indirectly for workers’ civic engagement by boosting workers’ economic standing relative to their managers and providing more opportunities for workers to shape the terms of their working conditions (Freeman and Medoff 1984). The past literature on workplace democracy strongly suggests that workers who have greater control and voice over their jobs are more likely to carry that participation into other areas of their lives, including politics, because their experience on the job boosts their sense of self-efficacy, their politically relevant skills, and their interest and expectations in civic participation (see e.g. Greenberg 1986; Greenberg, Grunberg, and Daniel 1996). As workers have fewer options for such input and participation as unionization declines, I expect worker political participation to fall. Yet another mechanism might flow through workers’ sense of security: Past research has underscored that perceptions of economic risk and insecurity are materially and cognitively demobilizing, leading individuals to become less involved in politics (see e.g. Levine 2015; Ojeda 2018).6

Employer and worker labor market power

Important as deunionization has been, I also focus on another, related dimension of declining worker power: the labor market power that workers have relative to their employers. This factor is intended to capture the net result of the changes in labor market policies, institutions, and conditions that may have advantaged employers over workers (see e.g. Bivens and Shierholz 2018). These changes include deunionization but go well beyond it to count the erosion of the minimum wage and other labor market regulations, as well as the rise of employer practices like “fissuring” that involve employers shedding legal and financial responsibility for their workers through franchising, subcontracting, or reclassifying workers as independent contractors (Weil 2014).

This factor also captures labor market slack: local labor markets, whether due to national macroeconomic policy or more geographically specific reasons, that have higher levels of unemployment. Slack in the labor market in turn will make it harder for workers to find alternative work—and therefore grant employers more economic power while making workers less secure in their jobs. Independent of prevailing economic conditions, some employers—for instance, a hospital network or meat-processing plant in rural counties (i.e. static monopsony; Azar, Marinescu, and Steinbaum 2019; Benmelech, Bergman, and Kim 2018)—might have greater clout in the labor market because of market concentration. And workers themselves may have their own preferences over jobs that make it harder for them to find comparable work—for instance, preferences based on commuting time or child care arrangements—therefore giving employers greater leverage over the terms of their jobs (i.e. dynamic monopsony; Manning 2005).

In all of these cases, I anticipate that lower levels of worker market power ought to increase workers’ sense of insecurity—and therefore dampen their likelihood of participating in civic engagement and political interactions in the workplace. I also anticipate that lower levels of worker bargaining power will reduce the likelihood that workers have the voice and input into their working conditions that might lead to the sort of politically relevant skill development and use described above. And lastly, I anticipate that the greater insecurity these workers face will make them more cautious of doing anything that could potentially result in them losing their job, and that includes talking politics.

I measure this concept of worker bargaining power by asking respondents whether they felt they could find another job with about the same income and benefits they had at the time of the survey (“About how easy or difficult would it be for you to find a job with another employer with approximately the same income and benefits you have now?”). Ten percent of workers reported that it would be very difficult, 29% said somewhat difficult, 23% said neither easy nor difficult, 25% said somewhat easy, and 14% said very easy. This question is intended to capture the balance of worker and employer labor market power, since workers who feel they have stronger exit options should have more economic power relative to their employers (for similar uses of this survey item, see e.g. Hertel-Fernandez 2018; Kalleberg and Marsden 2013).

A substantial union difference that reaches fewer workers

I assess how workplace political interactions and skills vary across each of these two measures of employer power, beginning with union membership. Compared with their nonunion counterparts—and consistent with the long line of work I reviewed above—union members are substantially more likely to be politically active in the workplace and to report using politically relevant skills on the job. Unions, through their internal governance and operation, provide opportunities for members to use skills like public speaking, running meetings, fundraising, and managing teams for even blue-collar workers whose direct work might not involve those things. Table 6 compares how the use of politically relevant skills differs by union membership, and it shows that union members are more likely than nonmembers to use all of these skills but especially fundraising, managing teams, or convincing others of arguments.

Politically relevant skills, by union membership: Share of respondents who report ever using political skill, by type of skills and union membership status

| Political skills | Nonunion | Union |

|---|---|---|

| Working closely with others on a team | 88% | 90% |

| Public speaking | 46 | 56 |

| Organizing and running meetings | 51 | 57 |

| Convincing others of an argument | 47 | 59 |

| Managing a team | 52 | 64 |

| Delegating tasks or activities to others | 65 | 71 |

| Fundraising or asking people for money | 21 | 46 |

Source: 2019 Workplace Political Participation Study. Union subgroup sample sizes: member: 182; nonmember: 1,030.

The union difference in politically relevant skills extends even to less-educated workers, especially those with a high school degree or less. Although we should be cautious of the small survey sample size of less formally educated union members, Table 7 reveals that unionized workers with a high school degree or less look much more like college-educated workers than other less-educated workers outside of the labor movement. In fact, Table 7 shows that unionized workers with a high school diploma or less are more likely than college-educated workers to report any experience with fundraising or asking people for money—no surprise given the importance of dues and contributions to political action committees for labor unions.

Politically relevant skills, by union membership and education: Share of respondents who report ever using political skills, by type of skill and education level/union membership status

| Political skills | Nonunion, high school or less | Union, high school or less | College or more |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working closely with others on a team | 79% | 79% | 96% |

| Public speaking | 26 | 48 | 68 |

| Organizing and running meetings | 35 | 46 | 71 |

| Convincing others of an argument | 27 | 49 | 67 |

| Managing a team | 38 | 58 | 68 |

| Delegating tasks or activities to others | 52 | 60 | 79 |

| Fundraising or asking people for money | 18 | 53 | 30 |

Source: 2019 Workplace Political Participation Study. Union and education sample sizes: nonunion, high school or less: 303; union, high school or less: 41; college or more: 514.

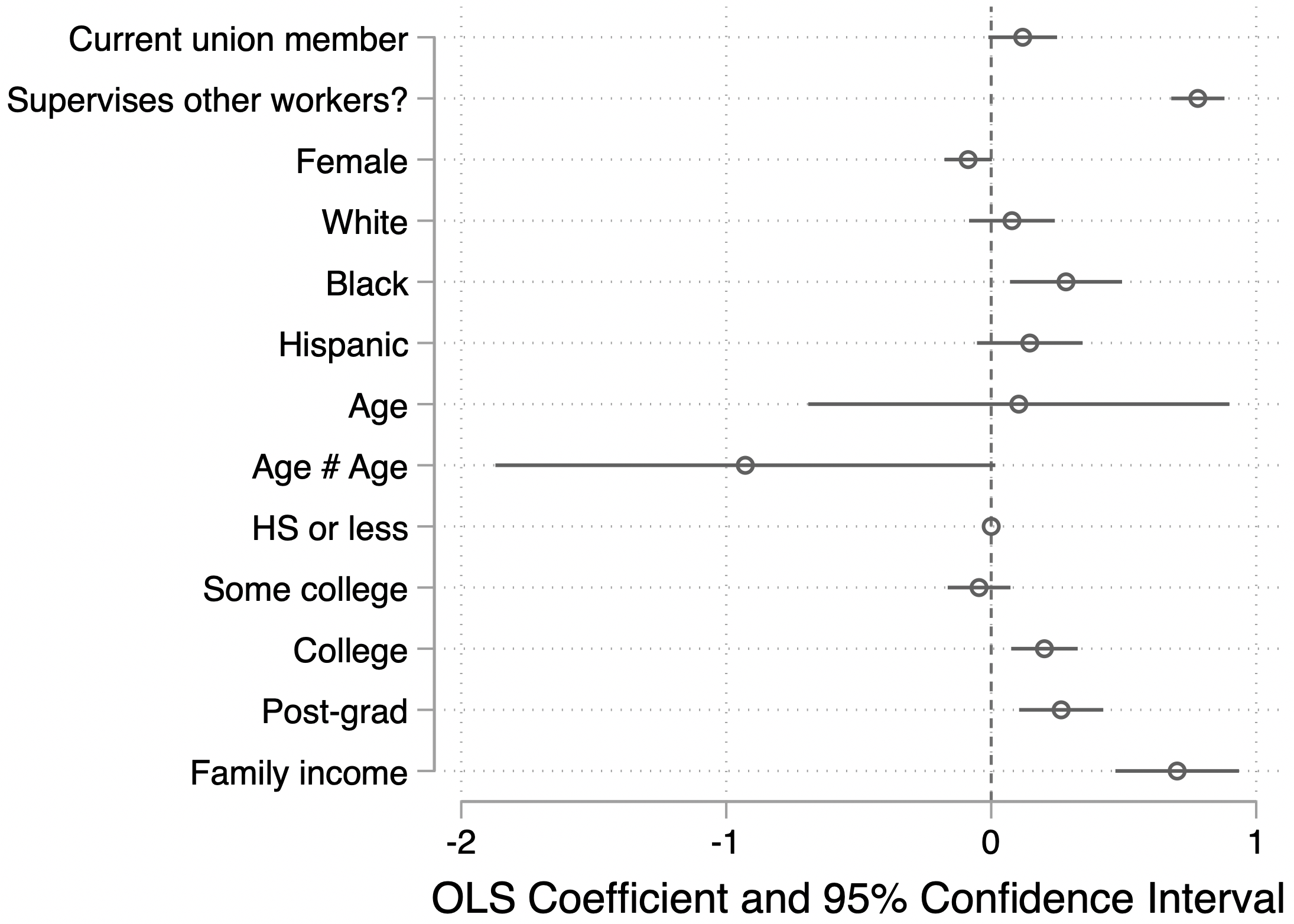

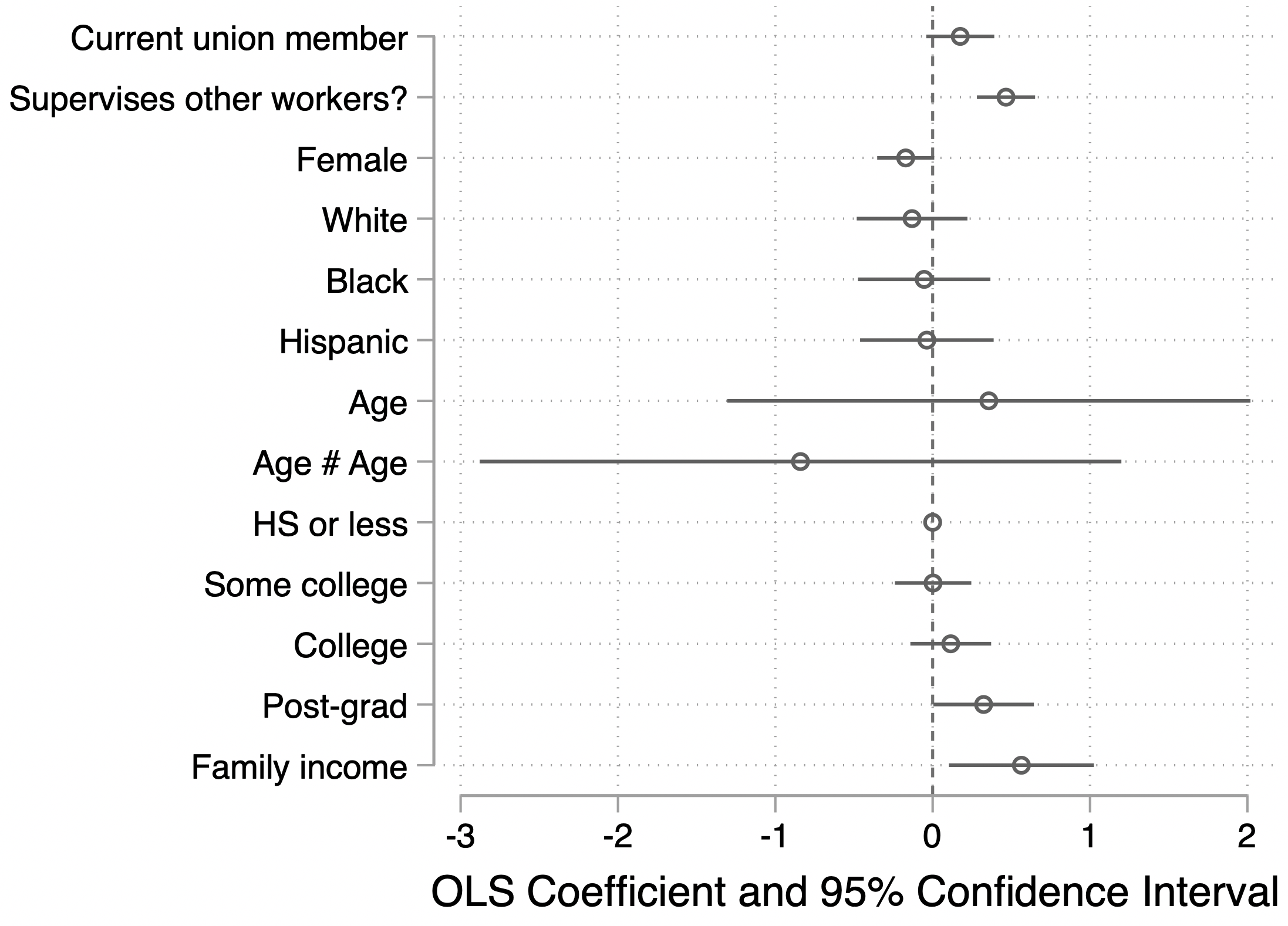

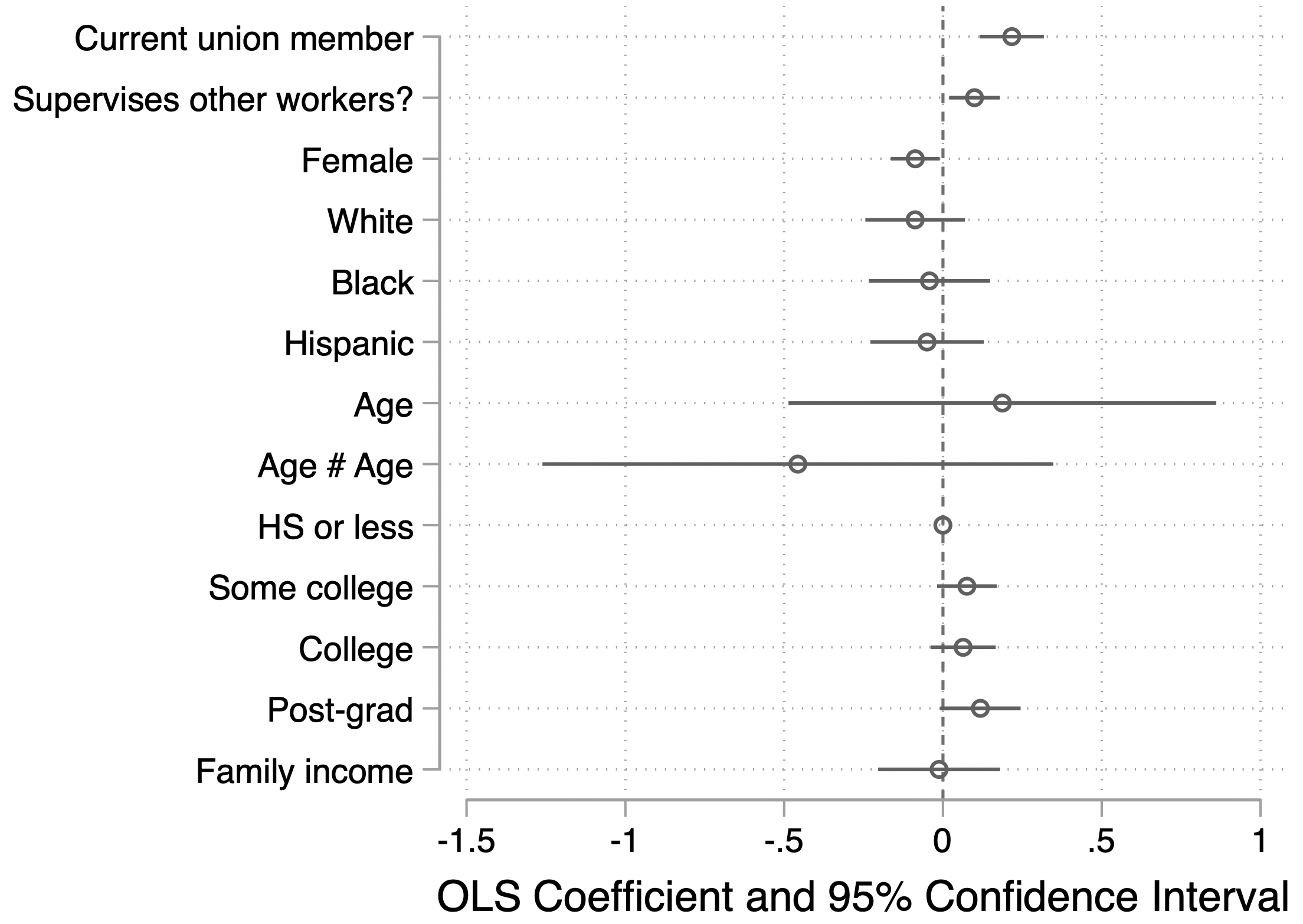

One question is whether the union difference we observe in Tables 6 and 7 is due to what unions are doing with their members (a union effect), an underlying difference in the types of workers and jobs represented in the labor movement (a compositional effect), or the choice of particular workers to join unions (a selection effect). While I cannot definitively answer the question with these data, I can compare the use of politically relevant skills between union members and nonmembers while adjusting for a range of relevant worker and job characteristics including gender, race and ethnicity, age, education, family income, managerial status, and occupation and industry.7 The outcome of this analysis is an average for the frequency with which survey respondents report using each of the politically relevant skills, from “never” (coded as 1), “a few times per year or less” (2), “a few times a month” (3), and “at least once a week” (4). Across survey respondents, the average political skill score, on this scale of 1 to 4, was 2.16.

After adjusting for all of the other job and worker characteristics, union members scored about 0.12 points higher on the use-of-skills measure than nonmembers. That is about twice as large as the gap in skills use between a worker with a high school degree or less and a worker with some college experience. Although we cannot be certain that this difference represents a causal effect of unions on their members, it does suggest that the union difference is unlikely to come solely from demographic differences across members and nonmembers or the fact that certain types of occupations and industries are more likely to be unionized than others. (See Appendix B for full regression results.)

Next, we turn to union differences in political discussions at work. Again, we observe that union members are more likely to participate in political conversations with coworkers than are nonmembers: 42% of nonmembers reported never having conversations with coworkers, compared with 30% of members. The difference is even more striking when we consider political conversations with fellow union members, since the vast majority (over 90%) of nonunion workers reported never having political conversations with union members. By comparison, about 60% of union members said that they had political conversations with their fellow unionized workers.8

Just as with politically relevant skills, the union difference is largest for workers with the least formal education, as illustrated in Figure F, which compares frequency of political conversations by nonunion workers with a high school degree or less, unionized workers with a high school degree or less, and workers with a college degree or more. Among nonunion workers with a high school degree or less, more than half report never having political conversations with their coworkers, but that rate falls to about 30% for their unionized counterparts. The figure for all college-educated workers is identical, meaning that unionized workers with a high school degree or less look just like workers with a bachelor’s degree when it comes to having political discussions with coworkers.

Political discussions at work, by union membership and education: Share of respondents who engage in political discussions at work, by frequency and union membership/education level

| Political discussions at work | Nonunion, high school or less | Union, high school or less | College or more |

|---|---|---|---|

| Never/not applicable | 52% | 31% | 31% |

| A few times per year or less | 14 | 30 | 23 |

| A few times per month | 16 | 21 | 24 |

| At least once a week | 18 | 19 | 22 |

Source: 2019 Workplace Political Participation Study. Union and education sample sizes: nonunion, high school or less: 303; union, high school or less: 41; college or more: 514.

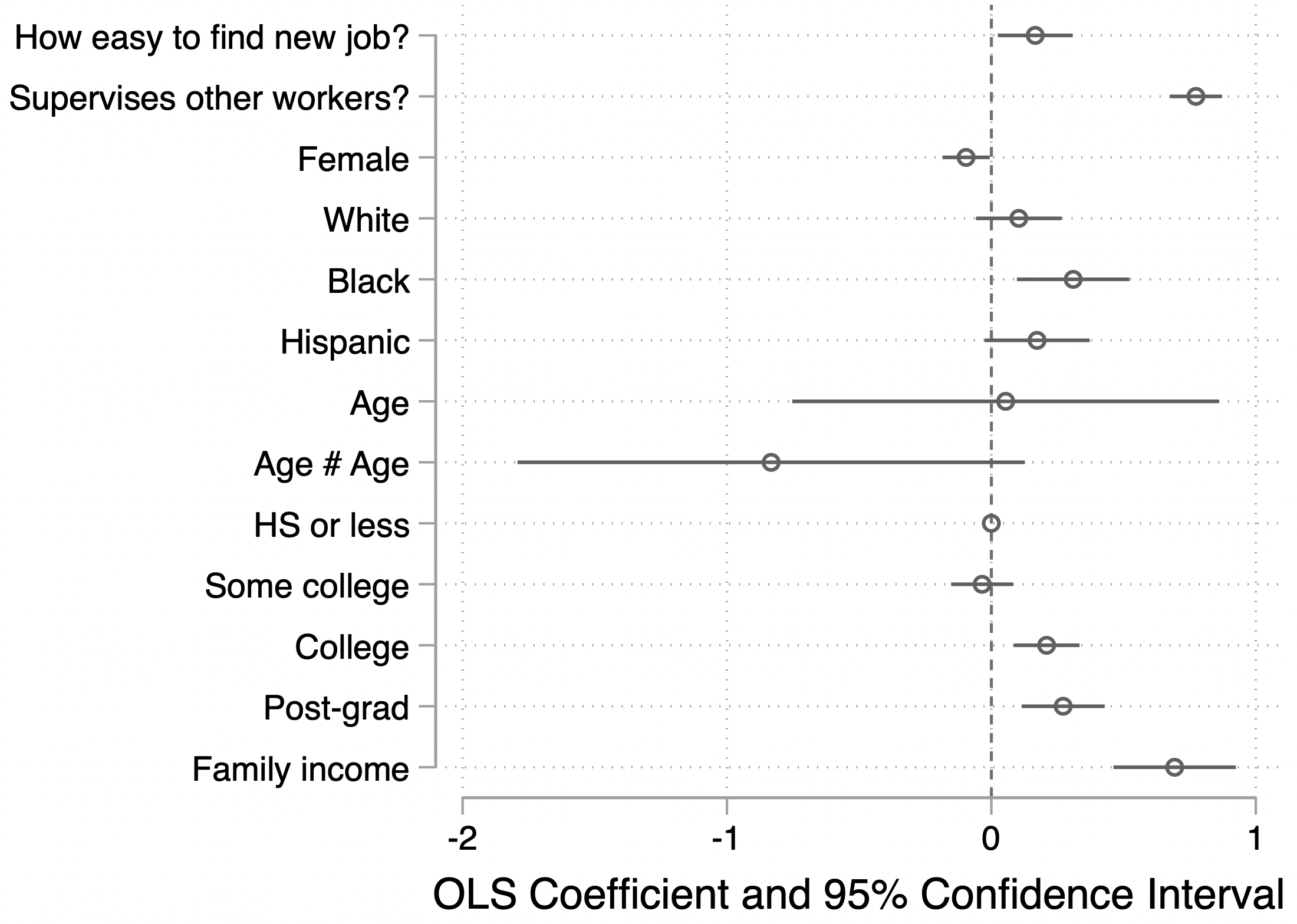

This picture does not change much when I adjust the union difference in political discussions for other worker and job characteristics (as I did above). In analyses where the outcome is whether a worker says that he or she never discusses politics with coworkers, union members are about 11 percentage points less likely to give that response than nonunion workers. That is roughly equivalent to the difference in political discussion rates between a worker with some college and one who has received a four-year college degree.

Lastly, I turn to coworker political opportunities and invitations. Here too we see a marked difference between union and nonunion workers, as reported in Table 8, with unionized workers being much more likely to report all forms of coworker political interactions. Thirty-six percent of nonunion workers reported any political interaction, compared with 58% of union members. The difference was especially large for attending political meetings, supporting political causes or campaigns, and learning about new political issues.

Coworker political interactions, by union membership: Share of respondents who report interactions with coworkers, by type of interaction and union membership status

| Interactions | Nonunion | Union |

|---|---|---|

| Asked to support a political candidate, campaign, or issue | 9% | 24% |

| Asked to register to vote or to vote | 15 | 20 |

| Asked to attend a political event or meeting | 7 | 21 |

| Changed my mind about a political issue | 8 | 17 |

| Told me about a political issue I hadn’t thought about before | 21 | 27 |

| Any political interaction | 36 | 58 |

Source: 2019 Workplace Political Participation Study. Union subgroup sample sizes: member: 182; nonmember: 1,030.

As with the previous cases, the union difference was especially large for less formally educated workers, illustrated in Figure G, which compares political opportunities reported by nonunion workers with a high school degree or less, unionized workers with a high school degree or less, and workers with a college degree or more. Unionized workers with a high school degree or less report roughly the same—or even higher—levels of workplace political interaction as college graduates. In fact, looking across all interactions, unionized workers with a high school degree or less were more likely to report any political interaction than were workers with a college degree.

Coworker political interactions, by union membership and education: Share of respondents who engage in political interactions at work, by type of interaction and union membership/education level

| Coworker political interactions | Nonunion, high school or less | Union, high school or less | College or more |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asked to support a political candidate, campaign, or issue | 6% | 21% | 14% |

| Asked to register to vote or to vote | 9% | 18% | 18% |

| Asked to attend a political event or meeting | 3% | 14% | 13% |

| Changed my mind about a political issue | 6% | 12% | 11% |

| Told me about a political issues I hadn’t thought about before | 18% | 22% | 25% |

| Any political interaction | 27% | 51% | 44% |

Source: 2019 Workplace Political Participation Study. Union and education sample sizes: nonunion, high school or less: 303; union, high school or less: 41; college or more: 514.

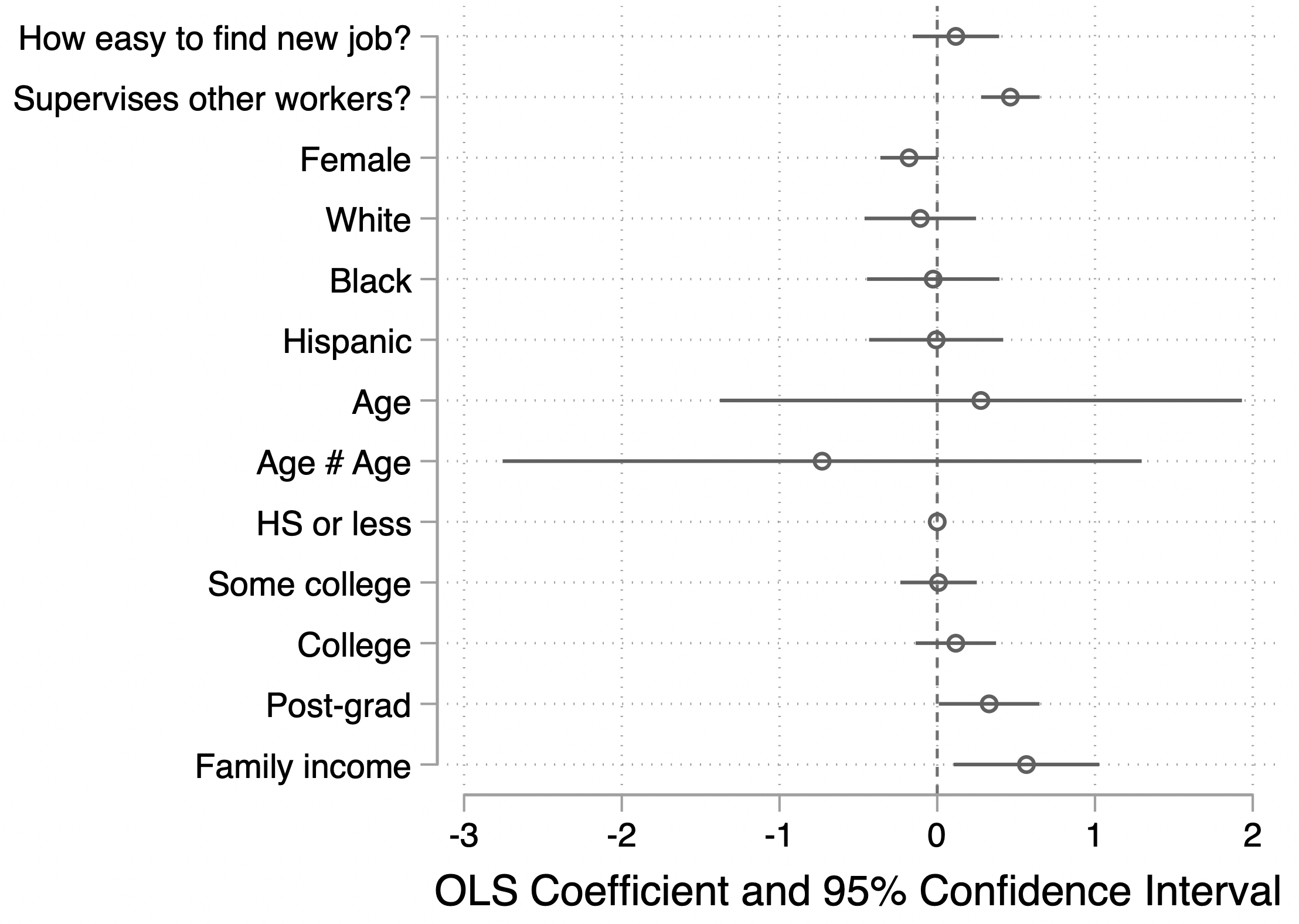

These union differences remain after adjusting, as done above, for other worker and job characteristics: Union members were on average about 22 percentage points more likely to report any coworker political interactions than were nonunionized workers controlling for all the other workplace and worker characteristics. This was by far the largest difference I observed across the three political outcomes in the workplace, representing a difference greater than the gap between workers with a high school degree or less and those with a post-graduate education.

Across the board, then, union membership is related to greater political skill building and more political discussion and engagement—and union membership may be especially important for closing the gap between workers with more and less formal education (and incomes). These findings suggest that the decline of the labor movement may have made it more challenging for many workers, particularly workers who face social or economic disadvantage because of their education or income, to engage in politics in the workplace.

Worker labor market power and workplace civic engagement

The second economic change I consider is the labor market power that workers have relative to their employers. Table 9 compares the proportion of workers reporting that they never use any of the politically relevant skills at their job by how easy they say it would be to find alternative jobs with comparable pay and benefits. Table 9 separates responses for workers reporting the most and least difficulty doing so, and shows that, with the exception of working closely on teams, those workers who report that it would be very difficult to find another job say that they also are less likely to use any of these skills. Figure H similarly shows that across all skills, workers reporting higher levels of labor market power were also more likely to say that they used those skills at least weekly.

Politically relevant skills, by worker labor market power: Share of respondents who report ever using political skill, by type of skill and level of labor market power

| Political skills | More power (say it is very easy to find new job) | Less power (say it is very difficult to find new job) |

|---|---|---|

| Working closely with others on a team | 88% | 88% |

| Public speaking | 55 | 41 |

| Organizing and running meetings | 55 | 44 |

| Convincing others of an argument | 53 | 50 |

| Managing a team | 57 | 42 |

| Delegating tasks or activities to others | 66 | 54 |

| Fundraising or asking people for money | 36 | 16 |

Source: 2019 Workplace Political Participation Study. Worker labor market power subgroup sample sizes: very easy: 179; very difficult: 135.

Weekly use of politically relevant skills, by worker labor market power: Share of respondents who report weekly use of political skill, by type of skill and level of labor marker power

| Percent of respondents | More power (“very easy to find job”) | Less power (“very difficult to find job”) |

|---|---|---|

| Working closely with others on a team | 61% | 58% |

| Public speaking | 25% | 11% |

| Organizing and running meetings | 23% | 14% |

| Convincing others of an argument | 23% | 16% |

| Managing a team | 32% | 21% |

| Delegating tasks or activities to others | 36% | 26% |

| Fundraising or asking people for money | 16% | 2% |

Source: 2019 Workplace Political Participation Study. Worker labor market power subgroup sample sizes: very easy, 179; very difficult, 135.

As before, we might wonder whether these differences reflect the kinds of jobs that workers hold or other worker characteristics, especially their formal levels of education. Yet even after adjusting for worker and job characteristics, I still identify a large gap in the average use of politically relevant skills between workers with more and less labor market power. The difference in the average use of all these skills (on the 1-4 scale, as above) between a worker reporting that it would be “very difficult” or “very easy” to find alternative work is 0.40, roughly the same size as the gap between workers with some college and a four-year college degree. The gap by employment arrangements also remains when I focus exclusively on the nonunion workforce. (See Appendix B for full regression results.)

Next, I consider the frequency of political discussions across workers with varying levels of labor market power. Here too I find clear differences: Nearly half of workers reporting that it would be very difficult for them to find comparable work said that they never discussed politics with coworkers, compared with around 35% of workers saying it would be very easy to find comparable work. Workers who reported greater labor market options also said that they were more likely to discuss politics more frequently too: 28% of workers reporting it would be very easy to find alternative work said that they discussed politics at work at least once a week, compared with 16% of workers who reported it would be very difficult. These differences remain even after adjusting for worker and job characteristics, as well as when I focus exclusively on the nonunion workforce.9

Finally, I do not identify a clear connection between worker labor market power and coworker political interactions. While there is a difference in the frequency of coworker political exchanges and opportunities by workers’ self-reported exit options—with workers in a stronger labor market position reporting more coworker mobilization—that difference disappears when I adjust for worker and job characteristics.

Are workers finding alternative sites for political engagement and discussion outside of the workplace?

The analysis presented so far implies that changes in the economy that have weakened worker power on the job may have also eroded opportunities for workplace-based political discussion, skill-building, and mobilization. One big remaining question is whether workers are finding alternative sites in their lives for political opportunities outside of their jobs. We might be less concerned about the patterns identified if workers can gain skills or participate in political discussions elsewhere in society—for instance, through churches, neighborhoods, or civic groups.

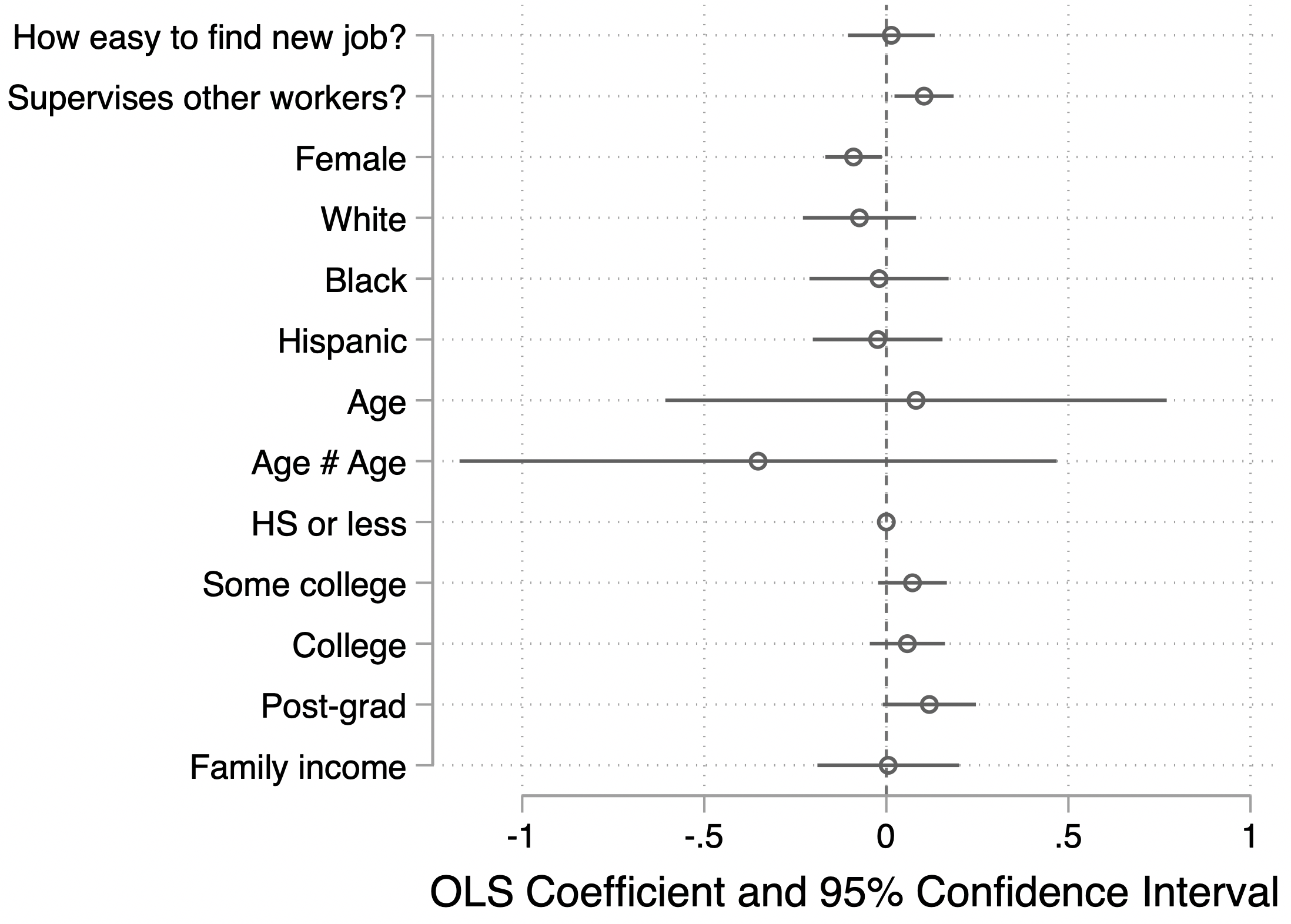

I cannot provide a definitive answer to this question for each of the political outcomes examined thus far, but I can focus on political discussions, since I asked workers to provide an accounting of their political conversations in the workplace and also across other sites in their lives, including churches or religious institutions, civic or community organizations, schools, and neighborhoods. If workers were finding alternative sites for political discussion outside of the workplace, we would expect that nonunion workers and less economically secure workers would be more active discussing issues in these nonwork sites. But this is not what I find. If anything, current union members and workers reporting greater labor market power are more likely than nonunion workers and less-secure workers to report engaging in political discussions outside of the workplace.

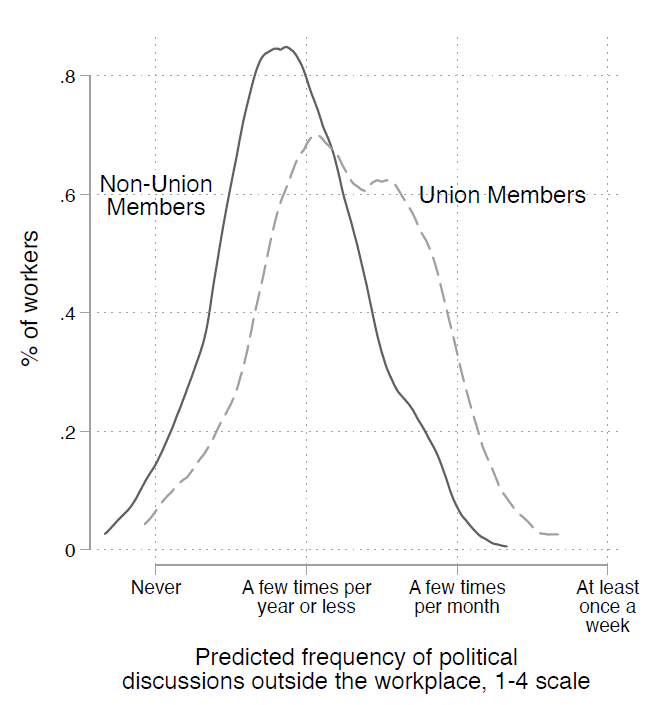

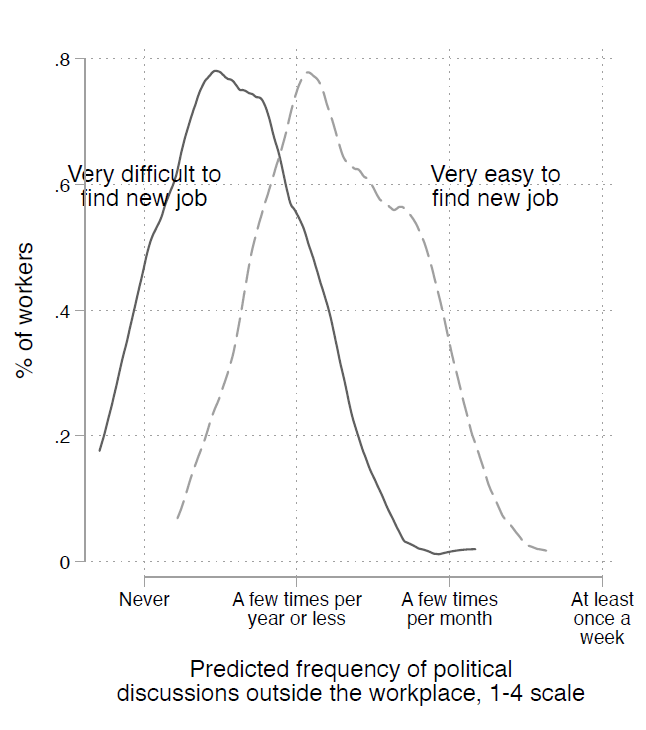

Figure I documents the predicted difference in the average level of political discussion that workers reported for nonwork social networks (those related to family, friends, schools, churches, neighborhoods, or community groups) by union membership and worker labor market power. These results adjust for other worker and job characteristics (and therefore are predictions, not actual frequencies). The figure shows the distribution of political discussion by union membership (in the left plot) and worker labor market power (how easy it would be for workers to find another comparable job, in the right plot). The solid line indicates the distribution of responses for nonunion workers or workers who would have a hard time finding another job, while the dashed line indicates the distribution for union members or workers who would have an easy time finding another job. The union member distribution is shifted well to the right of the nonunion curve, indicating that union members report more frequent political discussions outside of the workplace, even after adjusting for other worker and job characteristics. The same is true for the distribution of political discussion by worker labor market power: Those workers reporting that it would be easier for them to find another job are more likely to report more frequent political conversations outside of the workplace. Taken together, these results suggest that the decline of worker power in the workplace may have weakened political engagement not only on the job but also potentially beyond it too.

Summing up—and lessons for labor market policy in the Covid-19 pandemic

The analysis presented here from the 2019 Workplace Political Participation Study suggests that the shifting balance of power in the workplace between rank-and-file employees and their employers may have had political as well as economic consequences. As workers have lost ground relative to the businesses and organizations that employ them, workers may have also lost opportunities for building political skills and voice at their jobs. Consistent with many prior studies, I show that unions boost political opportunities for workers, especially workers with less formal education. Union decline has thus meant that many workers—above all, more socioeconomically disadvantaged workers—lack opportunities for building civically relevant skills, discussing politics with coworkers, and learning about ways to get involved in political causes and campaigns.

Union membership, moreover, was the only one of the two economic measures I studied that led to increased political mobilization at work—with boosted opportunities to directly participate in the political process. This should not come as a surprise, since unions offer workers both stronger economic standing relative to their employers and an organizational structure through which they can exercise political voice (e.g. Andrews et al. 2010; Han 2014). Of the two changes in workplace power I consider, union decline is therefore the most significant. Still, a key contribution of this paper is to document how union decline, despite its importance, is only part of the overall story of changing civic engagement and political voice. I have also tracked whether shifts in employer labor market power matter independently of the weakening of the labor movement. Across the nonunion workforce, workers who reported greater labor market power were more likely to report using job routines and tasks that they could apply to politics and to report more frequent political conversations with their coworkers.

The results from the WPPS should be seen as a start, not an end, to a research agenda centered on workplace power and voice. Much more research remains to understand precisely how each of the mechanisms laid out here works in practice, and to explore how these mechanisms play out in different sectors and occupations. The WPPS provides a national picture on these patterns, but there are good reasons to expect that the link between workplace power and political participation varies depending on the nature of individual businesses and working conditions (e.g. Greenberg, Grunberg, and Daniel 1996). More too remains to be done to understand how these changes have unfurled over time, since my survey represents only a snapshot of the workforce. And while I attempted to adjust my comparisons for a variety of worker, firm, and job characteristics, we ought to see these results as being suggestive—not proof positive—of a causal link between worker power and political participation. Future work ought to identify opportunities for more rigorous causal identification, be it through exogenous variation in worker power (including workplace field experiments) or interviews and ethnographies.

Even with these caveats, however, there are troubling implications of the results presented in this paper. Most worryingly, there is no indication that workers who have lost economic standing in their jobs are replacing the political engagement that they might have otherwise found at work elsewhere in their lives. And if anything, I have shown that workers who retain power in the workplace—especially union members but also those who report stronger labor market options—are more likely to participate in politics outside of the workplace as well.

With fewer opportunities for political engagement and activism at work, the shift in economic power away from workers may have diminished the voice that workers, especially rank-and-file workers, can exercise in politics—and therefore the incentives that elected officials have to respond to their needs and preferences. Past research has documented how labor unions boost the responsiveness of elected officials to the policy demands of low-income and working-class Americans (e.g. Feigenbaum, Hertel-Fernandez, and Williamson 2019; Flavin 2016; Gilens and Page 2014; Hacker and Pierson 2010; Stegmueller, Becher, and Käppner 2018). The results presented in this paper provide detailed mechanisms for why labor unions matter for political representation, showing how unions can create civically relevant skills and opportunities among their members at work. But they also show how broader shifts in the labor force, namely heightened worker insecurity, may have also independently weakened the political clout of working-class Americans.

Although the WPPS survey data were collected before Covid-19, they offer some indication of the likely consequences of the pandemic on workplace civic participation. The picture is not good—and suggests that the Covid-19 pandemic may undermine the civic potential of the workplace, especially for already-marginalized workers, including low-wage workers, those with lower levels of formal education, and racial and ethnic minorities.

Perhaps the most immediate consequence of the crisis is the challenge it poses to regular workplace social interactions. With workers either working from home or working in socially distant ways, the Covid-19 pandemic makes it harder for workers to have the kind of daily social interactions that the WPPS identified as contributing to political engagement (see e.g. Moss 2020). Many workers with caretaking responsibilities also face daunting challenges navigating their jobs in addition to caring for children or other family members as schools and other caretaking facilities remain closed—responsibilities that might make it harder to engage in civic activities with coworkers over a sustained period (Alon et al. 2020).