Opinion pieces and speeches by EPI staff and associates.

[ PRESENTATION TO THE U.S. HOUSE DEMOCRATIC TASK FORCE ON CHILDREN AND WORKING FAMILIES, FEBRUARY 11, 2004 ]

Tax burdens of the untaxed

How the Administration’s FY05 budget will impact children and working families

By Max Sawicky

Over the past dozen years, credits available to those who file income tax returns have grown to become a major source of aid to moderate and low-income families. In particular, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is now the second largest means-tested program run by the Federal government, with an annual cost exceeding $39 billion in 2005. Tax credits help lift families out of poverty and make work pay more (Porter et al, 1998). In confidence that my colleagues will comprehensively cover issues on the spending side of the budget, this testimony addresses problems and remedies pertaining to tax benefits for working families with children.

Since the passage of the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act (JGTRRA) last summer, tax-writing committees have dwelled on treatment of foreign sales corporations, manufacturing, energy, savers’ credits, and pensions, among other themes. If consideration of the tax burdens carried by persons with below-median incomes revives, some basic information provided here about the new lay of the land in regard to tax burdens on low- and middle-income families will be relevant.

In the wake of JGTRRA, a debate about children’s’ benefits under the President’s tax cuts briefly flared up. While implementation of most delayed features of the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act (EGTRRA) of 2001 would be accelerated, JGTRRA excluded two provisions from expedited phase-in. These would benefit low-income families with children. One was partial relief from the marriage penalty for recipients of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), and the other was an expansion of the refundable component of the Child Tax Credit (CTC). The latter received most of the attention.

Starkly differing bills in response to this debate quickly progressed in both houses of Congress, but resolution seems to have run aground. This testimony speaks to three features of the current debate:

- Proposals for expansion of refundable tax credits are criticized by discounting the tax burden on prospective beneficiaries (“They don’t pay tax”; “They get all of their payroll tax back from the EITC”);

- Legislators’ interest in eliminating marriage penalties has focused on taxpayers with positive net income tax liability. Relatively few resources were devoted to reducing the EITC marriage penalty;

- The supply-side priority of reducing high marginal tax rates is confined to the highest income taxpayers. Little discussion is devoted to reducing high marginal tax rates faced by low-income taxpayers.

The implication of these premises is that low-income persons are not directly or importantly affected by burdens or distortions in Federal taxes. The President’s budget for Fiscal Year 2005 largely preserves the implied, truncated view of tax policy. An exception is that the shibboleth of refundable tax credits is ignored in the case of the Bush Administration’s proposal for a refundable health insurance premium credit. Otherwise, little interest in reducing taxes not levied on income, estates, or gifts is evident.

It is true that over time, tax reform has increasingly eased the income tax burden on families in poverty (Kobes and Maag, 2003) and families with children (Carasso and Steuerle, 2003). Here our focus is not confined to those below the poverty line. More specifically, this testimony provides an update on tax entry thresholds and marginal tax rates affecting taxpayers with less than $50,000 annual income, not excluding payroll tax liability (see also Burman, Maag, and Rohaly [2002], and Seidman and Hoffman [2001]).

Why include the payroll tax? For about 70 percent of taxpayers, payroll taxes exceed individual income tax liabilities (Tax Policy Center, 2004). Present law explicitly reflects use of both the Earned Income Tax Credit and the Child Tax Credit to offset – or be limited by – payroll tax liability.

The no-child EITC benefit phases in and out at 7.65 percent, which is of course identical to the statutory payroll tax rate faced by the worker. For tax year 2003, the EITC could be said in this sense to defray a maximum of $383 of payroll tax for workers without children.

The Child Tax Credit includes a complicated provision – the “Additional Child Credit” – for families with three or more children. Under some circumstances their cash refund is limited by the difference between payroll taxes and their EITC benefit. Here again, the intent to circumscribe benefits according to payroll tax liability is made explicit in tax law, if opaque to the ordinary taxpayer.

Most economists believe that the portion of the payroll tax paid by the employer is borne by the worker, hence our calculations assume the payroll tax adds 15.3 percentage points to the worker’s marginal tax rate. By the same token, they means that our income numbers are proxies for income gross of the payroll tax. In other words, an income number should be read as net of the 7.65 percent of wages paid by the employer, hence gross income would be 107.65 percent of the nominal income number shown in our table and chart.

Tax Entry Thresholds and the “Marginal Child”

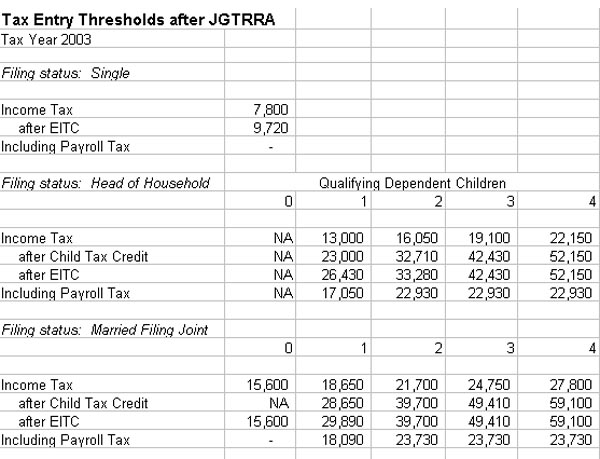

The table shows the tax entry thresholds after JGTRRA for tax year 2003 in three panels, for persons filing single (no dependents), heads of household (at least one dependent), and married (any number of dependents).

In the first line of each panel is income tax liability assuming use of the standard deduction, before including any credits. All of the calculations are based on the assumption that all income is “earned” and can be applied to determining CTC rebates and EITC benefits. They also assume that no other tax credits are claimed.

The first panel for single filers is limited to the effect of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and payroll tax. The standard deduction and exemption exclude income from income tax up to $7,800. The EITC available to couples and single persons without children pushes the tax entry point for those filing single up to $9,720. If the payroll tax is taken into account, the single filer’s first dollar of income is taxed. The combined payroll tax rate of 15.3 percent more than offsets the EITC credit for workers with no children, which phases in at 7.65 percent.

As noted above, the portion paid by the employer is included, hence the combined payroll tax rate of 15.3 percent goes to the overall marginal tax rate alluded to.

For household heads, the Child Tax Credit is added to the mix in the second panel. The second row shows that the CTC is effective in eliminating net income tax liability for poor and near-poor families.

The EITC is effective in lifting families above the poverty line (CBPP cite), but it has relatively little effect on the higher tax entry points. The EITC

begins phasing out at earnings of $13,700. By $32,000, the EITC is nearly exhausted. It is a program for workers and single parents earning very low wages. A couple working full-time each earning $8.75 an hour in 2003 is ineligible for the EITC.

The picture changes dramatically when the payroll tax is figured in. Single parents with income over $17,050 (for one child) or $22,930 (two or more children) face positive overall tax liability. For married couples, the analogous figures are $18,090 and $23,730.

Families in the ranges noted above pay positive taxes that could be offset by a faster phase-in of the CTC expansion, presently delayed until 2005. More far-reaching overhauls of tax-based child benefits are discussed in Sawicky (2003), Sawicky and Cherry (2003), Ellwood and Liebman (2001), Sawhill and Thomas (2001), and Carasso, Rohaly, and Steuerle (2003).

A second point stems from a question arising from the table. In the fourth row of panels for household heads and married couples, inclusive of payroll tax liability, the tax entry points do not rise as under the preceding row if the number of children exceeds two. The reason is that beyond the tax entry points for household heads or couples with two or more children – $22,930 ($23,730 for couples) – tax liability is outrunning the phase-in of additional CTC credits from the third or more children. At this point the EITC is phasing out, which exacerbates the effect, and the non-refundable dependent exemption is already “maxed out.” (The exemption ‘phases in’ with tax liability, so it could be said that it is indirectly income-tested in the backwards sense that it increases with income to its maximum value.)

The CTC has multiple components, one of which is indirectly conditioned in the same way. Up to a maximum of $1,000 per child, it expands with tax liability before credits. A second component grows at ten percent of earnings over $10,500.

For families with more than two children, there is the further complication of the “Additional Child Credit” (ACC), which expands to the extent the employee’s payroll tax liability exceeds her EITC benefit. Subject to the $1,000 maximum, the taxpayer can claim the greater of her “excess FICA payments” (a.k.a. “Full Refundability for Excess Dependents,” or “FRED”) or the ten percent rebate.

The EITC is directly income-conditioned. It phases in at 34 or 40 percent, for families with one or more than one children, respectively.

The consequence of income conditioning – credits growing with income – can be a lack of tax savings (or foregone increases in credits) from claiming an additional qualifying child. The “marginal child benefit” is often zero. One could view this as an undesirable violation of the principle of horizontal equity, in that it gives equal treatment (the same credit amount) to unequals (families with different numbers of children). Alternatively, the failure to “reward” the acquisition of additional children might be preferred.

In these calculations, for simple returns the new ten percent component of the CTC renders the Additional Child Credit irrelevant to a household head with three children. Their ten percent rebate is higher than the ACC at all income levels.

The maximum cash rebate available to a couple or single parent with as many as four children – about $4,800 – is not much greater than the EITC maximum for two children ($4,204). In other words, there is not enough overlap between the CTC and EITC to push up that maximum potential cash rebate more than about $600. The CTC can bring several thousand dollars in cash to large families in the $40,000 neighborhood. A very high proportion of families under median income levels with three or more children are completely shielded from positive income tax liability.

Supply-Side Economics for Waitress-Mom

Under current law, increasing the phase-in rate from ten to fifteen percent for the cash rebate component of the CTC is scheduled to take effect in 2005. Some have advocated immediate implementation, following the practice in JGTRRA applied to other deferred tax cuts.

The faster CTC phase-in causes the credit to “max out” at a lower income range. On the positive side, it provides higher cash payouts at lower income levels. On the negative side, because it exhausts the same $1,000 per child at a lower income level, it fails to offset increasing income tax liability over a slightly longer income range (about $2,000). Some taxpayers will be subject to an increase in their marginal tax rates. Doubtless, any affected taxpayers would be happy to get the money sooner rather than later.

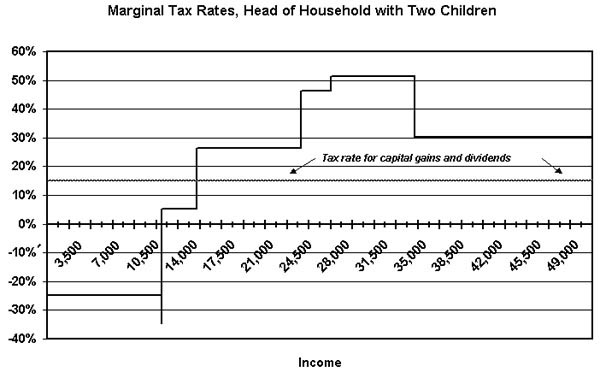

With or without the reform, as things stand marginal tax rates for many families below the median can exceed those of the idle rich. By “idle rich” is meant those who can enjoy a handsome standard of living without working, thanks to returns to equity holdings – dividends and capital gains. Senator John Edwards is making this point eloquently on the campaign trail.

Capital gains have always enjoyed preferential tax rates, relative to “ordinary income.” These rates were lowered further in 1997 and 2003. JGTRRA also vaulted dividends into the ranks of privileged, non-ordinary income. The upshot is that current marginal rates on income received predominantly by relatively high-income persons need not exceed 15 percent.

By contrast, marginal tax rates on households with incomes below the median ($42,400 in 2002) can exceed 50 percent. There is the 15.3 percent payroll tax on the first dollar of wages. There is the potential addition of 15 percent from the income tax. And there is the phase-out rate of 21.06 percent for EITC recipients with two children (15.98 for families with one child).

The figure shows marginal tax rates for a head of household with two children under 2003 post-JGTRRA tax law. Several perverse characteristics may be observed.

Most obvious is the irregular increases, lacking rhyme or reason. A rational pattern would be a consistent increase, a plateau, or a consistent decrease, depending on one’s preference for progressive, proportional, or regressive tax systems, respectively.

For those who favor progressive or flat rate taxation, the fact that marginal rates can be higher at lower income levels than higher ones is a deficiency. This pattern is more general than the income tax; Ellwood and Liebman (2000) write about the “middle class parent penalty” inherent in a broader set of tax and spending programs.

Finally, the magnitude of marginal tax rates deserves at least as much concern as that devoted to tax rates on wealthy persons and their capital income. For one thing, there are more people involved – economic decision-makers in their own right. In 2001, about 20 million taxpayers claimed the EITC, while taxpayers with income over $200,000 filed about three million returns. Secondly, the social implications of a working family failing to advance beyond poverty may be more eventful than a wealthy person discouraged from saving his marginal dollar.

Remedies

To raise tax entry points, in light of the dominance of the payroll tax in the tax burdens of most workers, there area at least two possible solutions. One is direct payroll tax relief. The payroll tax rate could be reduced, or some kind of standard deduction or ‘zero bracket’ could be instituted. These devices are undesirable. Both provisions reduce revenues going into the Trust Funds, burdening tax relief with a debate on long-term entitlement finance. The rate reduction’s lack of targeting is potentially undesirable. Setting a stand

ard deduction imposes significant administrative problems for employers of workers with irregular work histories and arrangements.

Better would be a credit through the income tax. Since payroll tax relief is in question, the credit must be refundable. The tax entry points shown above are founded on the income levels at which payroll tax liability overtakes refundable income tax credits. Income tax liability at those points has already been zeroed out by available credits.

What kind of credit? The other criticisms noted above provide some guidance.

The “marginal child” issue raised above arises from the pace of the credits’ phase-in. A faster credit build-up for a given amount of earnings would alleviate this shortcoming of current law. Some kind of phase-in is a practical political necessity, since otherwise refundable credits would be tantamount to a guaranteed income. On the merits, a faster phase-in has a greater impact in reducing marginal tax rates on the first dollar of earnings, thereby encouraging labor market participation.

To reduce the uneven pattern of marginal tax rates changes, multiple credits should be consolidated. To alleviate the perverse decrease of marginal rates at higher income levels, as well as to reduce overall levels of marginal tax rates, existing credits should be extended to higher income levels.

Insofar as the new credits are phased out at some income level, they retain an impact on marginal tax rates. Shifting such an effect to a higher income level is defensible. A laudable goal for a tax system, on grounds of equity and social costs, is to facilitate the passage of families though the “toll gate to the middle class.”

Consolidating credits entails unification of eligibility rules, presently one of the most complicated parts of the tax system for families with children. Fortunately, the Administration has proposed remedies to this problem. These remedies could be incorporated as the basis for a new, unified credit.

An example of such a solution may be found in H.R. 3655, the Progressive Tax Act (PTA) of 2003, introduced by Reps. Dennis Kucinich, Barbara Lee, and Bernie Sanders. General Wesley Clark has offered a similar proposal.

Is it foolish to talk about a new tax cut? Not in light of the possibility that some kind of broad-based, progressive tax cut may be the only way to accomplish what everyone knows will need doing – reclaiming the lion’s share of the revenue lost to a small minority due to tax cuts after 2000. Here again, the Progressive Tax Act offers a relevant menu of revenue raising measures that more than pay for the cost of its tax cut for working people.

The Federal budget outlook confronts the children’s cause with a dual burden. The more obvious and immediate is the rash of tax cuts over the past three years, used to invoke a dubious rationale for cutting spending programs relevant to the well being of children. Over the longer term, however, a disinclination to return taxes to their historic levels and to reduce the growth of health care spending, capped with a determination to eliminate deficits, adds up to a budget with no room at all for domestic discretionary spending (Steuerle, 2003).

In contrast to calls for austerity, ostensibly made “for the sake of the future generations,” Congress might consider that the surest way to aid future generations is to begin right now with living, breathing children. Making work pay more for parents is the most direct route towards brightening the fate of the nation’s children, and progressive tax reform should be among the first resorts.

References

Burman, Len, Elaine Maag, and Jeff Rohaly, “The Effect of the 2001 Tax Cut on Low- and Middle-Income Families and Children,” Tax Notes, Volume 96, Number 2, July 8, 2002, pp. 247-270.

Carasso, Adam, Jeffrey Rohaly, and C. Eugene Steuerle, “Tax Reform for Families: An Earned Income Child Credit,” Policy Brief, The Brookings Institution, Welfare Reform and Beyond, #26, July 2003.

Carasso, Adam and C. Eugene Steuerle, “Growth in the Earned Income and Child Tax Credits,” Tax Notes, January 20, 2003.

Ellwood, David T. and Jeffrey B. Liebman, “The Middle Class Parent Penalty: Child Benefits in the U.S. Tax Code,” Tax Policy and the Economy, MIT Press, Vol. 15, 2001.

Kobes, Deborah I. And Elaine M. Maag, “Tax Burden on Poor Families Has Declined Over time,” Tax Notes, Volume 98, Number 5, February 3, 2003, p. 749.

Maag, Elaine M. “Tax Entry Thresholds, 2000-2011,” Tax Notes, Volume 99, Number 6, May 12, 2003, p. 917.

Porter, Kathryn, Wendell Primus, Lynette Rawlings, and Esther Rosenbaum, “Strengths of the Safety Net: How the EITC, Social Security, and Other Government Programs Affect Poverty,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 9, 1998.

Sawhill, Isabel and Adam Thomas. A Tax Proposal for Working Families with Children, Welfare Reform and Beyond Policy Brief No. 3, The Brookings Institution, 2001.

Sawicky, Max B. “And Now for Something Completely Different: Doing a Fiscal U-Turn,” Tax Notes, Volume 101, Number 11, December 15, 2003, pp. 1353-1354.

Sawicky, Max B. and Robert Cherry, “Tax Credits ‘R Us,” Tax Notes, Volume 99, Number 3, April 21, 2003, pp. 419-422.

Seidman, Laurence S. and Saul D. Hoffman, “The Earned Income Tax Credit and the Child Tax Credit under the Tax Act of 2001,” Tax Notes, Volume 92, Number 4, July 23, 2001, pp. 549-554.

Steuerle, C. Eugene, “The Incredible Shrinking Budget for Working Families and Children,” National Budget Issues, The Urban Institute, No. 1, December 2003.

Tax Policy Center, “Historical Payroll Tax vs Income Tax,” http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/TaxFacts/TFDB/TFTemplate.cfm?Docid=230&Topic2id=50 , Tax Facts, Payroll, the Urban Institute and the Brookings Institution.

Max Sawicky is an economist at the Economic Policy Institute in Washington, D.C.