This piece originally appeared on U.S. News & World Report’s website

It’s been two and a half years since the official end of the Great Recession, but over 13 million people remain unemployed—more than 40 percent of them for over six months—and when you add in the underemployed, the number reaches nearly 24 million.

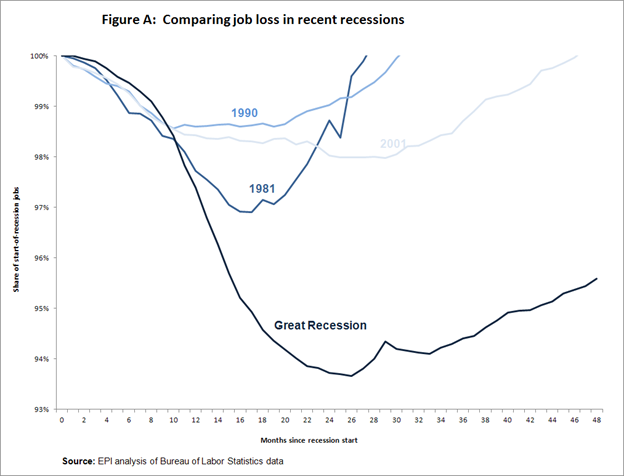

Charts like Figure A, below, have become pretty famous by comparing how long it takes job loss in recent recessions to be recouped (in this case the recessions that began in 1981, 1990, 2001, and the Great Recession). It’s effective in showing just how devastatingly large the gap in the labor market remains by historical standards. Four years since the start of the Great Recession, in December 2007, the labor market still has a far larger jobs deficit as a share of prerecession employment than at any point during even the very deep recession of the early 1980s.

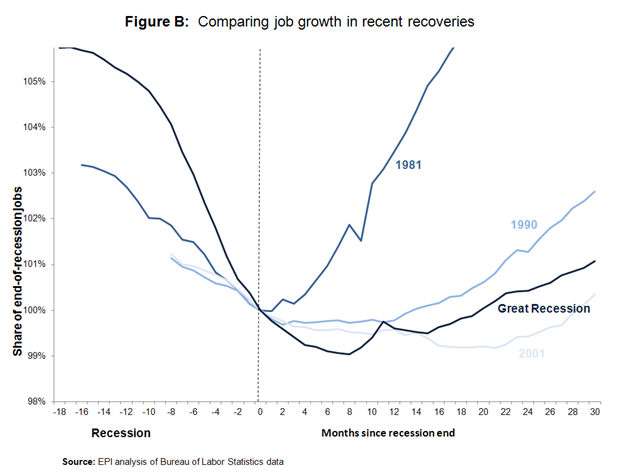

Figure A is not so effective, however, in painting a good picture of just why the jobs-gap remains so large. An interesting thing happens when the figure is re-oriented to compare job growth starting in recoveries instead of at the beginning of the recession. Unlike the more common recession comparison in Figure A, Figure B allows a comparison of the performance of the economy in the recovery phase following each recession.

Looking to the left of the dotted line, one sees that jobs fell much further and faster during the Great Recession than in previous recessions. But looking to the right of the dotted line, it becomes clear that job growth is actually not that much weaker in the current recovery: it just slightly lags behind the job growth following the recession of 1990 and is actually faster than the recovery following the recession of 2001 (and note, today’s job growth picture is even stronger when considering only private sector job growth—see the first figure here—due to unprecedented public sector losses in this recovery).

Figure B underscores that the key difference between this recovery and the last two is the length and severity of the recession that preceded them. These findings reject popular claims that job creation is currently being held back by new regulations or uncertainty on the part of businesses about tax policy or health insurance reform. If this were true we would expect to see much slower growth now (particularly relative to the early 2000s recovery, when these claims were not generally made).

Of course, this in no way lets today’s policymakers off the hook. The key problem in the current economy is depressed demand for goods and services, which (since workers provide goods and services) translates into depressed demand for workers. The nation’s labor market remains incredibly weak and the current pace of job growth will needlessly condemn millions of Americans to joblessness for years to come. Even at December’s job growth rate of 200,000—which was widely cheered as strong – it would take until 2019 to get back to full employment. Aggressive policies to create jobs—namely substantial fiscal support to bolster demand—need to become a top national priority.