The EPI Policy Center’s Josh Bivens and Hunter Blair submitted this letter to the U.S. House Committee on Ways and Means concerning tax reform on May 17, 2017.

May 17, 2017

Representative Kevin Brady

Chairman

Committee on Ways & Means, U.S. House of Representatives

Washington, DC

Representative Richard Neal

Ranking Member

Committee on Ways & Means, U.S. House of Representatives

Washington, DC

Dear Chairman Brady, Ranking Member Neal, and Distinguished Members of the Committee:

We welcome the opportunity to submit these comments to the Committee record on behalf of the Economic Policy Institute Policy Center (EPI-PC). EPI is a nonprofit, nonpartisan think tank created in 1986 to include the needs of low- and middle-income workers in economic policy discussions.

The Committee will convene on May 18 to discuss how tax reform could grow the U.S. economy and create jobs. While we agree that many tax policy changes could strongly benefit low and middle-income Americans, we do not think that Speaker Paul Ryan’s “Better Way” tax reform proposal and other likely principles of the Congressional majority’s plan for tax reform will do this. Instead, the outcome of efforts based on these plans and principles will simply lead to large, regressive tax cuts for corporations and the wealthiest Americans that will expire at the end of the budget window because they have not been paid for.1 According to the Tax Policy Center, in the first year of Speaker Ryan’s “Better Way” proposal, fully 76 percent of the benefits would go to the top 1 percent.2 Ten years later, this share will be an astounding 99.6 percent going to the top 1 percent. This level of regressivity is sometimes hard to fully understand. An easy way to grasp it is to contrast it with a lump-sum tax cut that shared benefits equally. A lump-sum cut would provide benefits for the bottom 60 percent of American households 10 times larger than what the “Better Way” plan would. But it would result in tax cuts for the top 1 percent that were 99 percent smaller.3

Of course, a lump-sum tax cut is just illustrative and proponents of “Better Way” style plans would argue that the incentive effects of their plan would spur growth. These effects are hugely overrated however. We would like to focus here in particular on the popular idea that corporate tax rate cuts are an effective way to spur economic growth.

First, proponents of corporate tax cuts often argue that U.S. corporations face higher tax rates than those of our peer countries, and claim that this differential hurts U.S. “competitiveness” (a word these proponents rarely define) and discourages companies from investing in the U.S. Consequently, they further claim that cutting corporate tax rates would increase American companies’ “competitiveness,” which they imply (but rarely argue directly) would redound to the benefit of most American families.

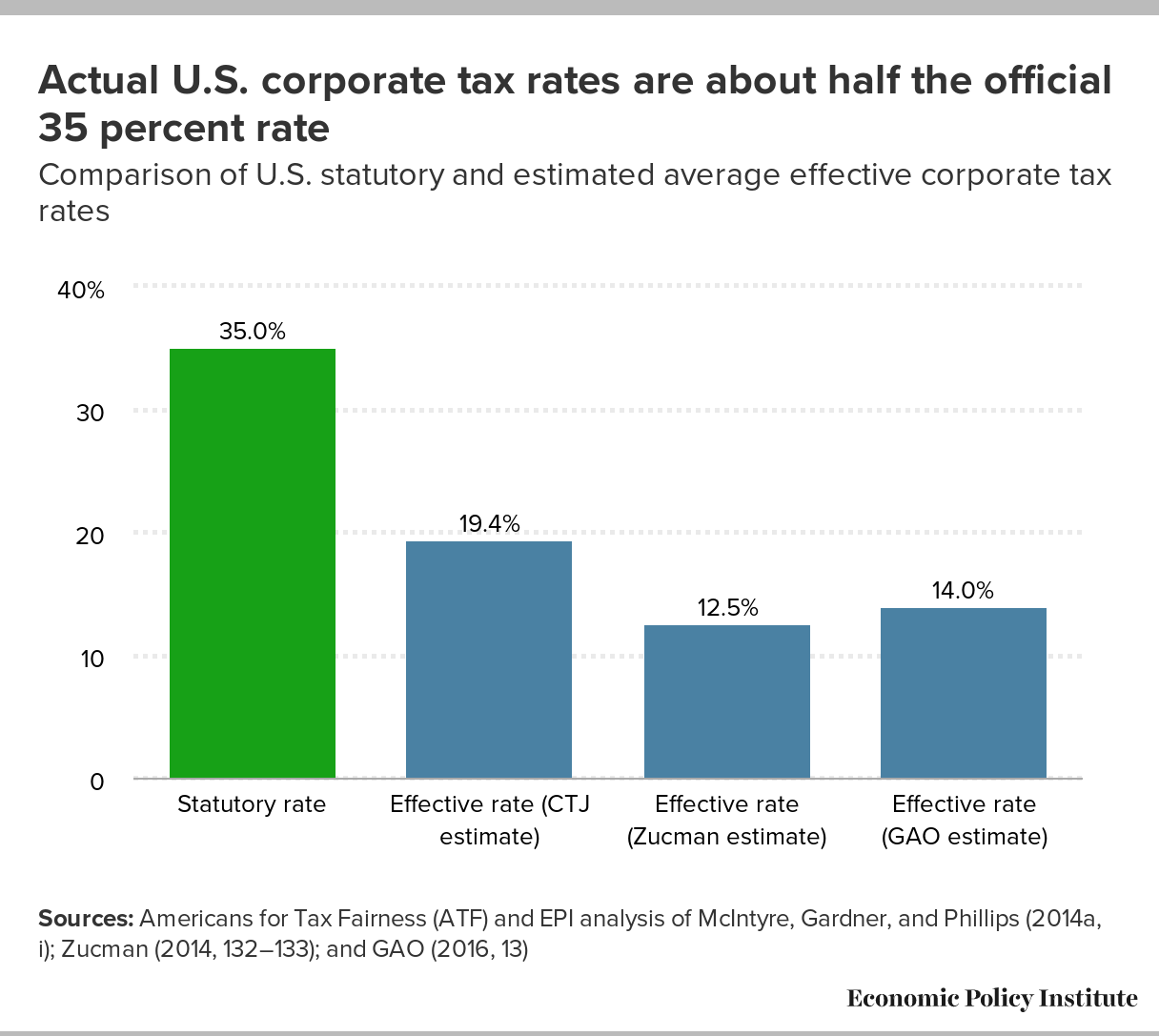

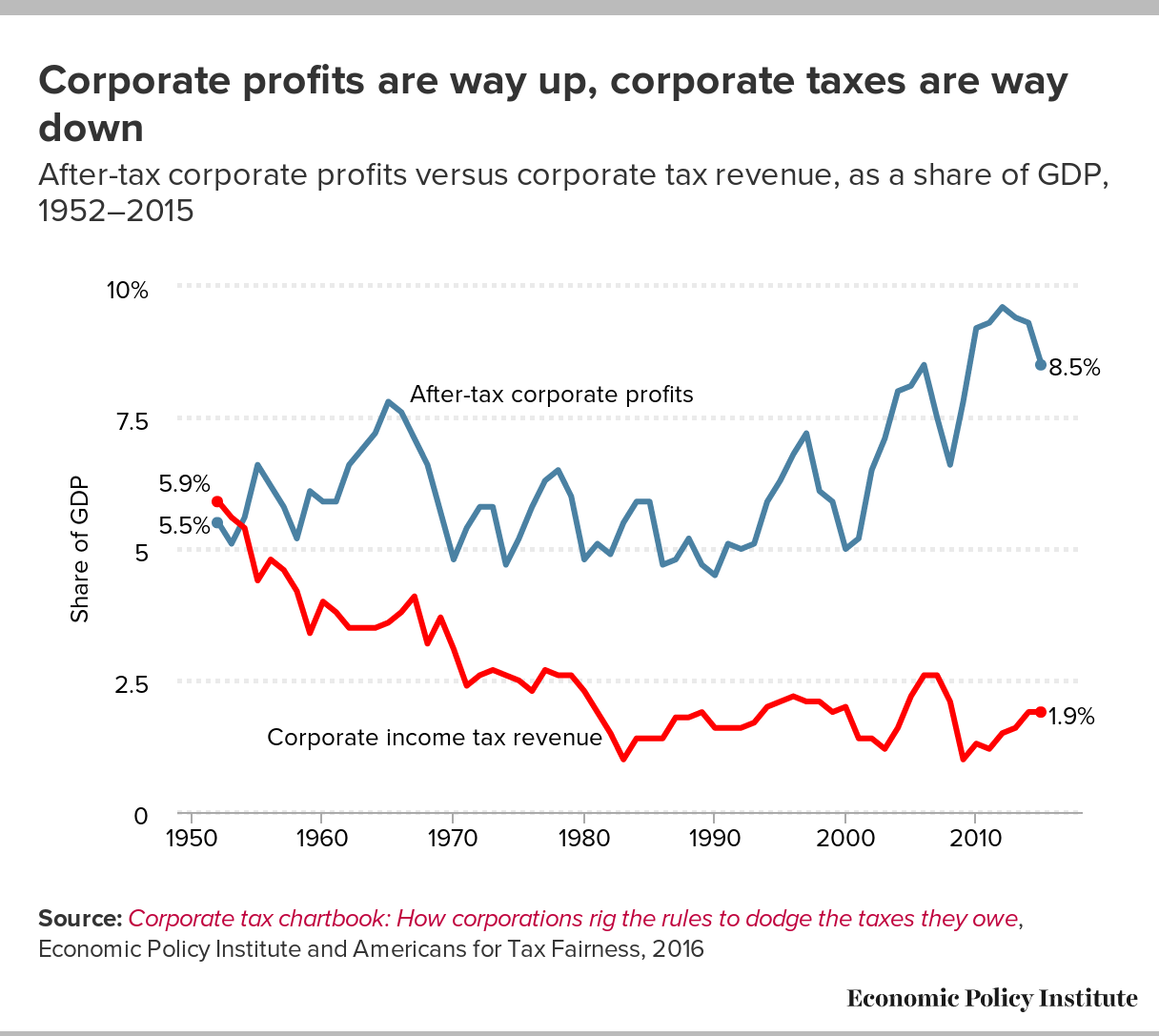

Our research has found this central argument—that U.S. corporations face high corporate taxes—to be empirically false.4 While U.S. statutory tax rates are higher, the effective tax rate paid by corporations is in fact roughly equivalent to the effective tax rates of our peer countries, due to loopholes in the U.S. tax code. Further, we find that even if the effective corporate tax rate were higher (if loopholes were closed), economic theory and data do not support the idea that cutting these rates would encourage further investment in the U.S. or benefit the vast majority of Americans. Instead, such cuts would primarily benefit a small number of high-income capital owners while increasing the regressivity of the tax system overall.

Claims regarding the economic benefits of cutting corporate tax rates rarely relate these cuts to the three influences that could boost living standards for the vast majority of American households: employment generation, productivity growth, and a more progressive distribution of income. Unless corporate tax rate cuts help boost any of these influences, they will not raise living standards for the vast majority and hence should not be a priority of policymakers.

Corporate rate cuts are inefficient as employment generators

Currently, the economy remains below full employment, with aggregate demand (spending by households, businesses and governments) still too low to absorb all the hours of work Americans want to offer. So, fiscal policy changes that spurred aggregate demand would be good. However, corporate tax cuts are the least-efficient way to boost aggregate demand and job creation.

In the short run, corporate rate cuts are passed through to shareholders, who are overwhelmingly well-off and much more likely to save rather than spend the extra money. If the government wants to cut taxes in the short run to spur employment, those tax cuts should be aimed at low- and middle-income households, not high-income shareholders. A better way to spur employment would be to boost public spending — on infrastructure or other public investments, or increases in income support programs.

Corporate rate cuts will have trivial effects on productivity

There is a better theoretical case that corporate tax cuts might help boost productivity. When the economy is at full employment, cutting the corporate rate should increase the post-tax return to capital. This should incentivize more private savings, which should in turn lower interest rates and increase capital investment.

The increased investment would provide workers with more and newer capital goods, boosting labor productivity. But while the theoretical channel linking corporate rate cuts and productivity growth is valid, there isn’t real-world evidence arguing that this link is strong. First, there’s already a well-known glut of savings. This savings glut has kept interest rates low for years and will likely continue to keep them low in the future.

With savings already high and interest rates already low, corporate tax cuts just won’t have much traction in boosting investment. Second, cutting the corporate rate can boost private savings, but if the rate cut isn’t paid for, this boost to private savings will be offset by decreased public savings (i.e., higher budget deficits). The deficit will increase, eventually pushing up interest rates and reversing the theoretical channel through which corporate rate cuts could increase productivity.

Corporate rate cuts clearly exacerbate post-tax inequality

Finally, besides being a terribly inefficient job-creator and having only weak real-world effects in boosting productivity, a strategy of cutting corporate rates is unambiguously regressive. The corporate income tax is typically assumed to ultimately fall largely on capital owners. Capital income is highly-concentrated at the top of the income distribution — with the top 1 percent of households holding 54 percent of all capital income.

In theory, some of this regressive effect could be mitigated by a boost to productivity. But, as we noted, this is far from a sure bet. But even if productivity does increase, it turns out that most of the benefits of productivity growth haven’t trickled down in decades. The hourly pay of the vast majority of U.S. workers has lagged far behind productivity growth due to rising income inequality.

Any policy change—including corporate tax reform—that is supported by claims that it will boost the living standards of the vast majority of American households must tell a convincing story of how it will (a) generate employment, (b) raise productivity, or (c) distribute income toward the vast majority. Needless to say, any policy change that cannot claim to boost the living standards of the vast majority is not worth doing.

If we wish to reform corporate tax policy to benefit the vast majority of Americans—and not just a wealthy few—we should not be talking about lowering corporate tax rates or offering other tax breaks to corporations; we should instead be focusing on closing loopholes in the system that have eroded the corporate income tax base, to ensure the corporate sector is paying its appropriate share of taxes.

Sincerely,

Josh Bivens, Ph.D

Director of Research, Economic Policy Institute Policy Center

Hunter Blair

Budget Analyst, Economic Policy Institute Policy Center

Appendices

Figure A

Figure B

Endnotes

1. Blair, Economic Policy Institute, 2017. “Likeliest outcome of tax reform is a deficit-financed tax cut for the rich that will expire in a decade.”

2. Nunns, Burman, et al. Tax Policy Center, 2016. “An analysis of the House GOP Tax Plan.”

3. Blair, Economic Policy Institute, 2017. “Republicans’ opening bid for tax reform is egregiously tilted to the rich.”

4. Bivens, Blair, Economic Policy Institute, 2017. “Competitive’ distractions: Cutting corporate tax rates will not create jobs or boost incomes for the vast majority of American families.”