President Obama’s Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform released its report this week. The commission is voting whether to approve it on Dec. 3, but it seems unlikely that co-chairs Erskine Bowles and Sen. Alan Simpson will garner enough votes among commission members to send the plan to Congress for expedited consideration. Even so, this plan is likely to be widely viewed as a starting point for a serious national conversation on deficits and long-term debt.

This commission was charged with putting together a plan to achieve two objectives: to balance the budget excluding interest payments by 2015, and to propose recommendations to improve the long-run fiscal outlook. Though it claims a noble set of guiding principles, the policy recommendations in the report do not conform to many of them, particularly those that claim an interest in not “disrupt[ing] the fragile economic recovery” and a pledge to “protect the truly disadvantaged.” Additionally, the plan completely ignores promoting job growth, other than a brief mention of a one-year payroll tax holiday. Job growth and job creation should be crucial components of any comprehensive plan that sets out to address long-term debt sustainability.

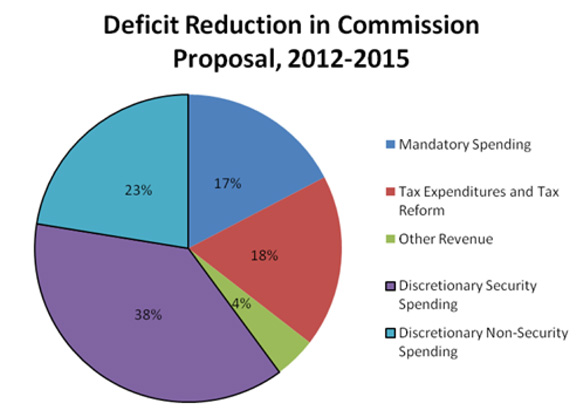

The commission plan goes after its short-term deficit goal largely by pursuing spending cuts, even as the report claims a desire to protect the disadvantaged and not disrupt the economic recovery. Around 25% of the plan’s deficit reduction from 2012-15, not including interest, comes from non-security discretionary spending. Cuts to discretionary spending (including security) make up over 60% of the commission’s short-term deficit reduction plan. Through 2020, the proposal’s discretionary spending cuts account for almost 60% of deficit reduction, while reduction due to tax expenditure and other tax-reform measures continues to make up less than 30% of the plan’s deficit reduction.

This upfront austerity would, if enacted, threaten our already tepid recovery. Cuts begin in fiscal year 2012, which begins in October 2011, less than a year from now. At that point, private-sector forecasters expect unemployment to remain around as high as it is today, with the Federal Reserve projecting an unemployment rate of 9.0% and independent analyst Mark Zandi projecting a rate of 9.7%. Economic indicators like this should spur the call for increased stimulus and policies promoting job growth, not deep cuts to spending, which will impact gross domestic product growth and adversely affect payroll employment. The recommendations in the plan achieve a total of around $4 trillion in deficit reduction through 2020, with around 20% of it coming from non-defense discretionary programs, a section of the budget that makes up a mere 5% of GDP.

Like the co-chairs preliminary proposal from mid-November, this plan caps long-term revenue collection at 21% of GDP, and eventually brings long-term spending down to that level as well. This arbitrary cap on revenue—which is less than revenue collection was under President Reagan—is a dangerous course to set as we face population aging and health care cost growth, both of which are expected to put pressure on government health spending. The cap additionally does not make sense given that this commission is charged with reducing the deficit, not with setting hard caps for spending or revenue levels.

Though the recommendations include a number of good ideas on how to increase efficiency and rein in long-term health care costs, such as reducing excess payments to hospitals and aggressively implementing and expanding payment reform pilot programs, their establishment of a long-term global budget for health care costs fails to address the root cause of growing national debt. By recommending a process for holding federal health spending to the level of GDP growth plus 1%, the commission only focuses on dealing with the symptoms of the budget problem, instead of the causes. The result would be a shifting of costs principally from the federal government to consumers and households, which is not a viable long-run solution.

On taxes, the proposal does not address the legacy of the Bush tax changes, which undercut revenue, but has instead opted to recommend simplifications to the tax code by lowering rates, broadening the base, and cutting “spending” within tax expenditures. Though the report claims a desire to keep the United States globally competitive, lowering individual and corporate tax rates further is a recipe for an inadequate revenue base and a less competitive America. Though many of the particulars are acceptable, such as paring back and making more progressive tax expenditures, the commission’s overall approach to taxation falls short of where it must be if it were serious about pursuing deficit reduction without affecting the truly disadvantaged. Focusing deficit reduction on spending cuts while using tax reform to lower rates would only continue the unfortunate trend of widening the income inequality we have seen over the last three decades.

This proposal contains some commendable policies. It cuts spending by the Department of Defense, attempts to build on cost-savings measures included in the Affordable Care Act, and treats capital gains and dividends as ordinary income. And on Social Security, it recognizes the need to increase the taxable maximum to cover 90% of earnings. While this is a good first step on Social Security, the plan phases these changes into effect very gradually—by 2050—and pairs this option with a number of other harmful policies that would result in reduced benefit levels for many Social Security beneficiaries. These harmful policy recommendations include an increase in the retirement age, which would affect overall benefits of lower-income individuals disproportionately, and a change in the methodology used to determine cost of living adjustments, which would result in a real-time benefit cut for individuals. Perhaps most importantly, the Social Security proposals within this plan would lead to very steep cuts for top and middle-income earners. Though the distributional analysis shows the lowest-income quintile would be mostly protected, the overall cuts would undermine Social Security by shifting it from a universally popular system of retirement supplement to a system targeted mostly at lower-income people. This could eventually lead to less overall support for the program.

In the plan’s introduction, the commission urges leaders and citizens to avoid “shoot[ing] down an idea without offering a better idea in its place.” The Our Fiscal Security project has put forth just such a budget plan, one that we feel offers better ideas. The Investing in America’s Economy, plan would bolster a painfully sluggish recovery rather than undermine it, and it would protect middle- and lower-income citizens. The commission’s plan falls short in a number of areas, including its approach to revenue collection, its likely disruption of the economic recovery, and its lack of focus on job creation, sorely needed at this time.

The Our Fiscal Security plan attacks rampant unemployment while fixing our long-term structural imbalances, recognizing that creating jobs and boosting economic performance should be the main goal in the current environment. At the same time, though, like the commission, the Our Fiscal Security plan recognizes that something should be done about long-term debt stability. To stabilize the debt while putting jobs first, the blueprint outlined in Investing in America’s Economy builds on economy-boosting investments while targeting progressive revenue increases, cutting spending, and pursuing health care c

ost containment (the biggest driver of growing debt levels). It succeeds in transitioning from a primary deficit to a primary surplus by 2018, leading to sustainable debt levels by 2020. In the long-term, the plan improves the trajectory of public debt, stabilizing it at 90% of GDP starting in 2025 and beyond. Long-term debt sustainability is impossible without job creation.

Investing in America’s Economy is a response to this commission’s proposal, as well as other budget plans released in recent weeks, that insist we must abolish deficits primarily through spending cuts, an approach that would harm citizens and drag down employment levels. Our plan offers another way: as a nation we can choose to actively create jobs and still demand fiscal responsibility.