Briefing Paper #210

Read more about economic stimulus

Because the United States is either already in a recession or is headed for one, policy makers need to act now to craft an effective economic stimulus package to spur growth and job creation. Without a stimulus of sufficient magnitude, the U.S. economy is likely to see a decline in growth or even a formal recession, leading to higher unemployment, declining or stagnant wages, and a host of other economic problems. A package that provides $140 billion of stimulus — 1% of GDP — would begin to reverse our economic course by creating an additional 1.4 to 1.7 million jobs.

What suggests the economy is headed toward such dire straits? The well-known troubles in the housing market have threatened the health of the broader economy over the past several months. Until now, it was hoped that the fallout from the declines in home prices would be contained — first to the sub-prime market, then to broader real estate-backed assets, and finally the hope was that the damage could be restricted to just the financial sector. Unfortunately, each of these barriers has been breached, and combined with a broader unraveling of credit markets, we can expect to see continued spillovers into other areas of the economy, most importantly the labor market.

A variety of indicators point to continued woes. Housing prices declined by a record 6.7% on an annual basis according to the most recent S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Index, and given the record inventories of unsold homes, prices are expected to fall further.1 Home foreclosures are on the rise: the largest U.S. mortgage lender, Countrywide Financial Corp., reported that foreclosures and late payments rose in December 2007 to their highest levels on record.2 Together with the rise in oil and gas prices, domestic consumer spending will almost certainly decline.

Furthermore, job growth slowed over the past year, and the weakness has begun to show up in the unemployment rate, which jumped to 5.0% in December 2007, significantly higher than the 4.5% rate in the second quarter of 2007. Though real gross domestic product was strong in the third quarter last year — in part because of strong export growth — the economy is widely expected to have slowed since then as the housing market turmoil, the credit market crisis, and $100-per-barrel oil prices take their toll.

Leading economists from both sides of the political spectrum — from Lawrence Summers3 to Martin Feldstein4 — believe there is a strong possibility of imminent recession, and that the current conditions signal that action is needed now from fiscal policy makers. Analysts at Merrill Lynch and Goldman Sachs believe that the United States may already be in a recession.5 If correct, the U.S. economy will see unemployment rates increase further, likely reaching at least 5.5% by the start of the third quarter of 2008, putting additional pressure on wages and incomes and further reducing consumer demand.

The stakes are high. In the last recession, the economy received only a mild boost from the 2001 tax legislation, primarily from a provision that provided a $300 rebate to most taxpayers. The bulk of the legislation, however, provided little immediate stimulus, and the economy — especially the job market — was very slow to recover: job growth, wages, and incomes all stagnated even well beyond the “official” end of the recession.

Criteria for an effective stimulus plan

There is always debate over what an effective stimulus package should look like. Many different policies are purported to stimulate the economy, but it is important to distinguish between those that will have their effect in the very near-term to offset rising unemployment this year and those policies that have longer-term effects. Any useful stimulus package should strengthen the recovery immediately and create more jobs in 2008. Some obvious examples of policies that fail this criterion are the ones just suggested by the Bush administration, including eliminating the estate tax and extending the high-end income, capital gains, and dividend tax cuts beyond 2010. These policies have nothing to do with the job creation we will need in 2008.

An effective, appropriate stimulus package should meet the following five criteria:

1. A stimulus package should generate growth and jobs to offset rising unemployment. The point of stimulus is to increase economic growth and thereby generate more jobs. The reason that employment growth is slowing and unemployment is rising (and will continue to do so) is that there is a shortage of demand for goods and services: we will have the capacity to produce much more than we will be consuming, and what is missing are customers able and confident enough to make expenditures.

The two feasible ways to boost demand are to increase consumer spending (for example through tax or monetary policy) or to increase government spending (at the federal, state, or local level). Any stimulus aimed at spurring more business investment will not be effective at this point, because business investment will remain sluggish until consumer and government demand picks up. For example, a recent study estimated that business investment write-offs and the dividend-capital gain tax reductions included in Bush’s tax packages had a small “bang-for-the-buck.”6 Without a rise in consumer demand, corporate tax relief and other business investment incentives will not be effective in stimulating growth.

Government spending is more effective than tax cuts in stimulating domestic demand for two reasons: a portion of the tax cut will be saved rather than spent immediately, and consumers are more likely than the government to spend on imports (rather than domestically produced goods). Approximately 10 cents per dollar of consumer expenditures will be spent abroad, while virtually every penny of investments in public infrastructure will be spent domestically. Especially problematic would be more tax cuts directed at the wealthy, which would not be as effective as tax cuts directed at the low- and middle-income households who would spend (rather than save) a larger share of any extra income.

2. A stimulus package should take effect quickly. The most frequently cited potential downside of stimulating demand through government spending is a concern that the spending will not yield economic activity quickly because of bureaucratic delay. A smart stimulus — such as the one proposed here — would have its impact within the next year. Ideally, an effective package would have some components that have immediate effect and others that might have impact in six months to a year, thus ensuring a solid foundation for the recovery. Without a stimulus, unemployment — now at 5.0%, half a percent higher than in the spring of 2007 — would likely rise throughout 2008, reaching around 5.5% by July, and 6.0% by the end of the year.

3. A stimulus package should raise current deficits but not affect the long-term budget outlook. The purpose of any good stimulus package is to boost immediate job growth. For this purpose we need one-time measures that, if the recession deepens, can be extended as necessary. Permanent, ongoing measures that will affect the budget two or three years from now are,

in most cases, inappropriate.7 Simply put, any stimulus proposal involving tax cuts and “pump-priming” expenditures must employ one-time, temporary measures. On the other hand, a deficit-neutral stimulus package is an oxymoron: if the plan does not raise the near-term fiscal deficit, then it has not expanded net expenditures in the economy and will not lead to new jobs.

4. A stimulus package should target unmet needs. Another goal of any good stimulus plan should be to meet, where possible, unmet social needs. For instance, it is widely acknowledged that there is a huge backlog of necessary school and bridge repairs and new construction projects. A temporary spending increase for such infrastructure would be doubly beneficial in that it would meet the other criteria listed above but also address an acknowledged, pre-existing need. Other examples could include funding needed sewage-treatment plant construction or making public facilities energy efficient.

5. A stimulus package should be fair. The distribution of wages, income, and wealth in the United States has become vastly more unequal over the last 30 years. In fact, this country has a more unequal distribution of income than any other advanced country. Therefore, a criterion for favoring one stimulus plan over another should be that the plan avoids exacerbating income inequality and, wherever possible, acts to lessen current inequalities. A temporary increase in federal revenue-sharing with the states, for example, would fulfill this criterion well by helping preserve public school spending, Medicaid for low-income families and low-income elderly in nursing homes, and other state programs that could face cutbacks due to state fiscal crises.

| Three components of a comprehensive jobs stimulus plan

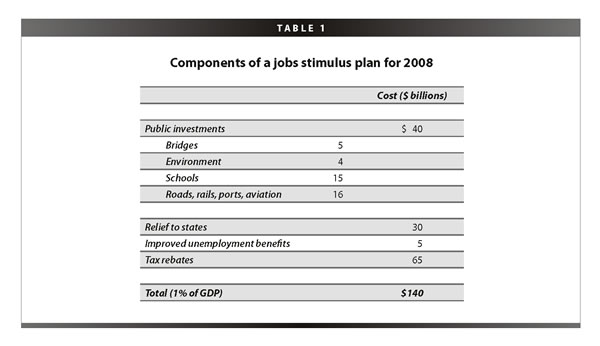

Between spending and tax cuts, an economic stimulus package should equal 1% of GDP, that is, about $140 billion over one year (based on the most recent quarterly GDP figure, 2007q3). Such a stimulus should be split three ways: 1) Federal spending for individual supports and accelerated public investments, 2) Aid to states and localities, and 3) Targeted tax rebates. |

Federal spending

Additional federal expenditures should aim to: 1) provide additional supports to those immediately displaced by the recession, and 2) accelerate federal investments in priority areas, including bridges, roads, schools, and environmental infrastructure.

Unemployment compensation

Unemployment compensation is particularly stimulating to the economy because the unemployed spend virtually every dollar they receive and tend to do so on necessities found in their local economy. Mark Zandi of Economy.com estimates the stimulative effect of unemployment compensation at $1.73 for each dollar spent, and a 1999 Department of Labor study estimated that each dollar of unemployment compensation boosts GDP by $2.15.

Unemployment compensation should be available to every American who seeks suitable work but cannot find it, especially as the economy slows and hundreds of thousands or even millions of workers become unemployed. To help maintain consumer demand and prevent the economy from entering a vicious cycle of slowing growth, as unemployment rises benefits should be extended beyond the regular 26 weeks currently provided.

In the last recession, national unemployment grew by 2.7 million from December 2000 to March 2002, yet failed to trigger the national program that would have extended benefits under current law. Congress finally enacted a special program of additional benefits — Temporary Extended Unemployment Compensation — in March 2002, but not until the official recession had been over for four months.8

As we head into the next recession, Congress has two choices for reform: either replace the Extended Benefits (EB) program or fix its trigger mechanism. The better choice is to replace the EB program — which only extends benefits by 13 weeks and splits the cost equally between state and federal governments — with a new, 100% federally funded program that triggers when unemployment reaches excessive levels. It makes no sense to burden state budgets with additional responsibility for unemployment compensation when the economy is slowing, thus reducing state government revenues and forcing cutbacks in state employment. In each of the past three recessions, Congress has ultimately faced up to this fact and enacted a supplemental program fully funded by the federal government. Rather than continue an ad hoc approach that always comes too late for many of the unemployed, Congress should enact a permanent federal program that triggers before unemployment reaches damaging heights. The right policy would be to extend benefits by 13 weeks when unemployment hits 5.5%, and another 13 weeks if it reaches 6.0%.

The other alternative is to reform EB. Federal law requires states to provide Extended Benefits when their Insured Unemployment Rate (IUR) — which measures the ratio of workers receiving unemployment compensation as a percent of the entire state workforce covered by unemployment insurance — reaches 5%, coupled with a 120% increase in the IUR over a base period. EB also triggers at a 6.0% state IUR regardless of its percent increase. Unfortunately, the unemployment rate among the insured bears little relation to (and is far less than) the percent of unemployed workers overall or to the state of the job market.

For example, the national average IUR today is less than 2.0%, yet even in the three states whose three-month average total unemployment rate was over 6.0% in December 2007 (Alaska, Michigan, and Mississippi), none had an IUR as high as 3.3%. The Advisory Council on Unemployment Compensation long ago recommended eliminating the IUR as a trigger and replacing it with a total unemployment rate trigger. When a state’s three-month average unemployment rate exceeds 5.5%, Extended Benefits should go into effect.

Nationally, current law calls for the EB to begin when the national average IUR reaches 4.0%. That trigger, too, should be replaced. When the three-month national unemployment rate reaches 5.5%, EB should be triggered in every state whose unemployment exceeds 5.0%.

The Senate should also immediately pass the Unemployment Insurance Modernization Act that is part of the bill already passed by the House of Representatives (HR 3920). The Unemployment Insurance Modernization Act would deliver benefits more broadly and provide $7 billion in incentives over a five-year period to states that adopt reforms to expand coverage among low-wage workers. This legislation would:

- provide UI benefits to workers who are only available for part-time work,

- enable workers who leave their jobs for compelling family reasons to qualify for UI benefits, and

- consider a worker’s most recent work history when determining eligibility for UI benefits.

Accelerating public investments in schools, transportation, and environmental protection

The most obvious response to rising unemployment is to put Americans to work building or repairing needed capital assets. Such work puts money in the pockets of hard working people who would otherwise struggle, and it can lead to higher productivity, better health, and better education of our children. The economic activity and jobs directly created by this spending have a beneficial ripple effect as, for instance, construction firms purchase materials and employees spend their salarie

s. The resulting stimulus would be geographically widespread. Such investments should emphasize repairs in which the work can start and be completed sooner.

The nation faces large deficits in public investment that need to be addressed. A particular benefit of this stimulus approach is that constructing a package that helps address these needs essentially accelerates investments that ought to be made in any case. In other words, public investments can in the short run boost job creation and in the longer run help advance productivity.

One widely held concern about including spending in a stimulus package is that there will be delays and the economic benefits will come too late to help offset the rising unemployment. While there may have been delays in programs decades ago, there need not be any now. We have identified areas of needed public investment where projects with completed plans are already identified — the only element missing is the funding. Consequently, spending can readily be targeted to projects that can begin within 90 days. This can and should be done as a one-time expenditure. Since many of the projects are repairs to existing infrastructure, the projects will be undertaken as well as completed relatively quickly.

If the recession deepens, then another round of spending can take place later. In any case, so many unmet needs have already been identified that construction could begin in a matter of a few months on billions of dollars of new construction and repairs for schools, for transportation (roads, bridges, etc.), and for environmental (water and waste treatment) projects.

Estimates of the effects of each $1 billion of construction spending vary widely, from an additional 14,000 to 47,000 jobs and up to $6 billion in additional GDP, according to the Federal Highway Administration. Slack demand caused construction employment to fall by more than 200,000 jobs in 2007, so there is a substantial experienced labor force ready to begin new projects.

Environmental infrastructure projects

High-quality drinking water and wastewater treatment are critical to protecting human health and the environment. There are 772 communities in 33 states and the District of Columbia with a total of 9,471 identified combined sewer overflow problems. Combined sewer overflows contribute to the ongoing contamination of the nation’s waters by releasing approximately 850 billion gallons of raw or partially treated sewage annually. In addition, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that between 23,000 and 75,000 sanitary sewer overflows occur each year in the United States, releasing between three to 10 billion gallons of sewage per year. The EPA estimates that more than $50.6 billion is necessary to address combined sewer overflow problems, and an additional $88.5 billion is needed to address sanitary sewer overflows.

According to a representative survey of its member wastewater treatment facilities by the National Association of Clean Water Agencies, communities throughout the nation have more than $4 billion of wastewater treatment projects that are ready to go to construction, if funding is made available. Funds can be distributed immediately through the Safe Drinking Water and Clean Water State Revolving Funds and designated for repair and construction projects that can begin within 90 days.

School repair and modernization

Public K-12 schools throughout the nation need to spend about $17 billion a year to maintain existing structures and grounds, far more than their current budgets allow. Federal funding for repair and maintenance could be spent quickly and efficiently, employing many of the more than 200,000 construction workers who lost their jobs in 2007, and the many more who will lose jobs as overall unemployment rises. Repair projects have the advantage of a short start-up time, as well as a short time to completion, thus fitting the bill of an effective short-term stimulus.

There are over 48 million children and another 6 million adults who attend or work in more than 95,000 public schools and administrative buildings on a daily basis. In 1999, the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) put the average age of the main instructional public school building at 40 years.9 Existing buildings, no matter what their age — but particularly older buildings?require ongoing maintenance and repair. While there is no national inventory of how much building space or land is used in support of K-12 public education, a conservative estimate puts this at 5.4 billion gross square feet of building area and nearly 700,000 acres of exterior land and site improvements.10 An industry standard for how much should be spent annually on maintenance and repair is 2% of the building’s replacement value. So a building that cost $20 million to build, in current dollars, requires about $400,000 per year for maintenance. Using this estimate of building inventory, the United States should be spending approximately $17 billion per year on public school facility maintenance and repair to catch up with and maintain its K-12 public education infrastructure repairs.

According to an NCES survey in 1999, however, 76% of all schools reported that they had deferred maintenance of their buildings and needed additional funding to bring them up to standard. The total deferred maintenance exceeded $100 billion, an estimate in line with earlier findings by the Government Accounting Office (GAO). In just New York City alone, officials have identified $1.7 billion of deferred maintenance projects on 800 city school buildings.

Congress should appropriate $20 billion for a major summer school maintenance program — including such things as roof repair, painting, carpet replacement, landscaping, replacing toilet or sink fixtures and bathroom partitions, window replacement, and maintenance of heating and air conditioning systems. School districts could prepare to use these funds responsibly given even short notice. The funds should be allocated to State Education Agencies and distributed in proportion to the student population among all school districts.

Maintenance and repair of school buildings and grounds is labor intensive work. The skill levels of individuals involved in this work can range from unskilled laborer to highly skilled technicians, but mostly involve the skilled trades — painters, glaziers, carpenters, electricians, or plumbers. Funding made available to school districts can be used to engage contractors or to ensure the ability to retain maintenance workers on school district payrolls, who are often among the first laid off during economic downturns.

Highways, bridges and transportation projects

The U.S. Department of Transportation has identified more than 6,000 high-priority, structurally deficient bridges in the National Highway System that need to be replaced, at a total cost of about $30 billion. A relatively small acceleration of existing plans to address this need?appropriating $5 billion to replace the worst of these dangerous bridges?could employ 70,000 construction workers, stimulate demand for steel and other materials, and boost local economies across the nation. Only bridges for which architectural and engineering work has been completed, where construction could begin within 90 days, would be funded.

In a document entitled, “A Proposal to Rebuild America by Investing in Transportation and Environmental Infrastructure,” the staff of the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure has identified more than $70 billion in construction projects that could begin soon after being funded. All of the projects meet important needs of commerce as well as safety or environmental protection, and should be funded eventually. Starti

ng some of these projects sooner would provide a major economic stimulus and employ more than a million Americans, counteracting the job losses from slack demand and a slowing economy. An effective stimulus plan could include $16 billion directed at projects for roads, rails, ports, and aviation; only projects that can begin within three months would be considered.

State aid to offset reduction in tax receipts

During times of recession, state budgets are hit particularly hard. Reductions in tax receipts and cyclical increases in state spending put pressure on budgets — and since most states have balanced budget requirements, they are forced to either reduce spending or increase taxes in times of decreased economic activity. These actions perversely add to economic troubles by decreasing the total demand for goods and services, and thus intensify a recession. As such, direct federal assistance to states can help prevent these outcomes and stimulate the economy. In the last recession, Congress provided $20 billion in aid to the states, split between general revenue sharing and a temporary increase in the federal match for Medicaid. The same kind of assistance should be provided to the states once again, with $30 billion split equally between a general block grant and an increase in the Medicaid match.

There is mounting evidence that states are already feeling the pinch. Twenty-four states are either facing a shortfall for fiscal year 2009 or are expecting problems in the next year or two. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, just 13 of these states face a combined $23 billion shortfall.11

Tax policy

Tax policy can be an effective stimulus, but only if done on a temporary and “downscale” basis. Tax reduction should be targeted to those who are most likely to spend it immediately. Low- and moderate-income taxpayers are those who will be facing the most immediate budget squeeze due to the recession, and thus most likely to spend any extra money received through changes in tax policy. Estimates by Moody’s Economy.com indicate that each $1 in tax cuts targeted to low-income households would increase demand by $1.19.12 In contrast, tax reductions for capital gains and dividends would yield just $0.09 per dollar. Second, any tax cut or rebate ought to be immediate and temporary: the point is to stimulate consumer purchases now, and there is no need to lock in tax cuts for later years.

An effective way to add a broad-based boost to consumption in order to quickly generate economic activity and job growth is to provide an immediate, one-time, refundable rebate to anyone who has paid either payroll or income taxes for 2007.13 A total expenditure of $65 billion would yield approximately $350 or more per individual, and $700 per married couple.14 Basing the tax rebate on payment of either payroll tax or federal income taxes ensures that the rebate will effectively target low- and moderate-income taxpayers, many of whom do not pay income taxes.15

| Stimulus and the Deficit

Fiscal stimulus inherently involves additional federal expenditures and temporary tax reductions that will increase the short-term fiscal deficit. These efforts increase the total demand for goods and services, thereby increasing economic activity and jobs in a period in which we have rising unemployment and excess production capacity. If either the temporary tax cuts or spending efforts are offset by tax increases or spending reductions, then the stimulus package will be ineffective in raising total demand because the offsets take away with one hand what the stimulus provided with the other. Therefore, a stimulus plan that is “deficit-neutral” in this year makes no sense. It is possible, however, to consider a plan that is “deficit-neutral” over a five-year or longer period. |

Monetary policy will not be enough

Many economists typically believe that recessions can be better fought by the Federal Reserve. With the ability to quickly influence short-term interest rates, the Federal Reserve has a powerful lever to influence the economy and fight recessions. The current economic situation clearly calls for the Federal Reserve to aggressively lean against the current downturn.

However, there are several reasons to believe that monetary policy, while necessary, would not be sufficient to stimulate the economy under current circumstances. First, turmoil in the credit market makes it less likely that interest rate changes will lead to additional investments through traditional channels. Lenders are facing a crisis of confidence da– in both borrowers as well as in the reliability of asset valuations?and are wary of lending.16 Furthermore, housing prices may still have a long way to fall, so any boost coming from renewed demand for housing in the face of interest rate cuts will be muted. While a rate cut would still likely be beneficial, it is unlikely to have the same stimulative impact as in the past.

Furthermore, changes in monetary policy, once enacted, will take around a year to fully benefit the economy. Hence, while the Fed should continue to reduce interest rates, we cannot look only to monetary policy to provide the stimulus the economy needs today.

Finally, rising prices — especially for food and energy — and worries about acceleration of inflation may place additional constraints on monetary policy. Charles Plosser, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, recently was quoted as saying, “I am concerned that developments on the inflation front will make the Fed’s policy decisions more difficult in 2008.”17 Furthermore, risks of a disorderly decline in the value of the dollar might place further restrictions on the Fed’s willingness to reduce rates (or sustain low rates) during a recession.

Conclusion

Given the tremendous damage that a recession does to the employment, income, and health of millions of Americans, Congress should act quickly to keep the economy from stalling. A total package of $140 billion in federal spending on infrastructure improvements, aid to the states, additional weeks of unemployment compensation, and flat tax rebates would boost demand, create approximately 1.4 to 1.7 million jobs,18 and help keep the economy from sliding into a deep recession.

Endnotes

1. See S&P, “Broadbased, Record Declines in Home Prices in October According to the S&P/Case-Shiller® Home Price Indices” at http://www2.standardandpoors.com/spf/pdf/index/CSHomePrice_Release_122622.pdf.

2. Reuters, “Countrywide says foreclosures highest on record.” January 9, 2008, at http://www.guardian.co.uk/feedarticle?id=7211734.

3. Larry Summers wrote in the Financial Times, January 6, 2008, “The odds of a 2008 U.S. recession have surely increased after a very poor employment report, growing evidence of weak holiday spending, further increases in oil prices, more dismal housing data and further write downs in the financial sector. Six weeks ago my judgment in this newspaper that recession was likely seemed extreme; it is now conventional opinion and many fear that there will be a serious recession.” at http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/3b3bd570-bc76-11dc-bcf9-0000779fd2ac.html?nclick_check=1

4. Martin Feldstein was quoted in Bloomberg.com, January 7, 2008, “We are now talking about more likely than not? I have been saying about 50 percent. This now

pushes it up a bit above that.’ at http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601087&sid=aJ5SXq9NIPow&refer=home

5. See BBC News, “Recession in the U.S. has arrived.”

6. See M. Zandi, “Assessing President Bush’s Fiscal Policies,” Economy.com, July2004

7. Permanent changes that are appropriate include enhancements to automatic stabilizer programs. That is, programs such as unemployment insurance that would benefit the current economy while 1) also protecting the economy from future downturns, and 2) that would automatically ramp down once the recession isover.

8. The extension was still necessary because employment growth and unemployment levels did not recover for some time after the official end of the recession.

9. http://nces.ed.gov/surveys/frss/publications/2000032/index.asp.

10. Public schools vary in building and site size tremendously, but still cluster within a range that enables an informed estimation of building and land inventory. If space is estimated at a per student basis, we can achieve a reasonable estimate of the total U.S. inventory.

11. See Elizabeth C. McNichol and Iris Lav, “13 States Face Total Budget Shortfall of at Least $23 Billion in 2009; 11 Others Expect Budget Problems.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 18, 2007 at http://www.cbpp.org/12-18-07sfp.htm.

12. Mark M. Zandi, “Assessing President Bush’s Fiscal Policies,” Economy.com, July 2004.

13. An alternative would be to provide rebate to all adults regardless of tax-filing status. See Eileen Appelbaum and Richard B. Freeman, “Declare a Prosperity Dividend,” Issue Brief #150, Economic Policy Institute, February, 2001, at http://www.epi.org/page/-/old/issuebriefs/ib150/ib150.pdf

14. In 2005 there were 52.5 million joint returns, and 82 million non-joint returns, for a total of 187 million filers, according to the IRS. If we assume all filers will receive the maximum rebate, each individual would receive $348. However, since a fraction of filers will not receive the full rebate, the maximum rebate for a $65 billion cost will be slightly greater.

15. A rebate based on federal income tax alone would omit many low-income taxpayers who have no income tax liability, but still pay federal payroll taxes.

16. M. Feldstein, Wall Street Journal, Dec 5, 2007, “The current credit crunch reflects not only a lack of liquidity, but also a lack of confidence in the creditworthiness of counterparties and in the accuracy of asset prices.” At http://www.nber.org/feldstein/wsj120507.html

17. BBC, January 8, 2008, at http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/7176255.stm

18. This calculation assumes that a 1% stimulus would increase GDP and employment. The lower bound assumes a 1-1 increase from the stimulus, while the upper bound assumes the components of the stimulus would yield a GDP impact as estimated by M. Zandi, “Assessing President Bush’s Fiscal Policies,” Economy.com, 2004.