History Teaches Us We Need Race-Conscious Policies

In the current issue of The American Prospect, I charge that many liberals and civil rights advocates have been too quick to accommodate to a reactionary Supreme Court plurality that considers the nation’s racial problems to be solved or beyond remedy. The Court now says that institutions of higher education must be “colorblind” in their admissions procedures, because racial preferences are unacceptable unless designed as a remedy for specific state-sponsored acts to discriminate against African Americans. And such acts, the Court says, are no longer responsible for African Americans’ disadvantages.

It may well be pragmatically necessary for universities to operate within the confines of Court rulings by substituting recruitment of low-income students for African Americans and by seeking “diversity” in incoming classes. But necessary though these policies may be in the short term, they are flawed because the descendants of American slaves and the victims of government-sponsored Jim Crow rules, in the North as much as in the South, remain uniquely entitled to affirmative action. And while students from low-income families are easy to identify, it is much more difficult to remain colorblind while continuing to identify working and middle-class African American students who are the most deserving of university admission assistance.

Tax Gasoline, Save the Highway Trust Fund, and Help the Economy (and the Planet)

Continuing its recent habit of allowing a foreseeable problem to become a full-blown crisis, Congress has so far done nothing to prevent the looming insolvency of the federal Highway Trust Fund (HTF). The HTF is a dedicated account from which the U.S. Treasury draws to pay for road construction (and provide support for mass transit). Because the gasoline tax—the HTF’s primary source of dedicated revenue—has not been increased since 1993, more has been spent from the HTF than it has taken in for years. Since 2008, Congress has needed to transfer $54 billion from the U.S. Treasury’s general fund to the trust fund to prevent its insolvency. Unless Congress again transfers general funds to the HTF, or otherwise closes its funding gap, the trust fund is expected to go bust this August. And if highway spending were to be reduced to the level of current revenues for one year, because the trust fund “has no authority to borrow additional funds,” it would cost our economy 160,000 to 320,000 jobs, using my colleague Josh Bivens’s methodology.

I should note two things about this short history. First, there’s no particular economic problem facing the federal government here. HTF spending is already factored into the federal budget’s baseline. Continuing to finance its operations with general fund transfers will hence do nothing to increase overall projected federal budget deficits. Instead, this is largely an accounting problem—spending is constrained by the fact that, by law, HTF spending is supported primarily by a dedicated tax. Second, if policymakers nevertheless object to the fiscal non-problem of continuing to finance highway spending in part with general fund transfers, there’s obviously a simple solution. No, not a huge corporate tax break. Instead, we could just raise the federal gasoline tax.

The Truth Behind Today’s Long-term Unemployment Crisis and Solutions to Address It

Earlier this week, EPI economist Heidi Shierholz spoke on a Congressional Full Employment Caucus panel about policy fixes to the nation’s long-term unemployment crisis, convened by Rep. Conyers (D-Mich.). Other panelists included Betsey Stevenson, Member of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, and Judy Conti, Federal Advocacy Coordinator at the National Employment Law Project. Below is an excerpt of her comments, which explain why we remain in a long-term unemployment crisis, why the long-term unemployed will continue to face tough job odds without substantial policy intervention, and what can be done to address it.

The Great Recession officially ended five years ago this month, but the labor market has made only agonizingly slow progress towards full employment. We’ve had an unemployment rate of 6.3 percent or more for more than five and a half years; as a reminder, the highest the unemployment rate ever got in the early 2000s downturn was 6.3 percent, for one month. And even this headline unemployment rate probably overstates the true degree of labor market weakness, as it has fallen in large part in recent years because people have left the labor force in large numbers—and not just voluntary retirees. If the job market improves in coming years, it is very likely that many of these “missing workers” will return. Because of the ongoing weakness in the labor market, long-term unemployment remains extremely elevated. Though the labor market is headed in the right direction, unemployed workers still vastly outnumber job openings in every major industry, and the prospects for job seekers remain dim.

The labor force is comprised of employed people and jobless people who are actively seeking work. Before the Great Recession started, just 0.7 percent of the labor force was unemployed long-term. That shot up to 4.4 percent by the spring of 2010, and has since dropped part-way back to 2.2 percent. This may not sound high on the face of it, but it is still three times higher than what it was before the recession began and represents 3.4 million long-term unemployed workers. Furthermore, outside of the Great Recession and its aftermath, it is higher than at any other time in more than 30 years, including the entirety of the two recessions prior to the Great Recession. Importantly, it is also far higher than any period in the past when Congress has decided to end extended unemployment benefits. In short, we remain in a long-term unemployment crisis, even if you wouldn’t know it judging from too many policymakers’ actions.

It is important to note that there’s no real puzzle as to why long-term unemployment is high: economic growth remains extraordinarily weak. And this weakness is driven simply by an ongoing shortfall of aggregate demand (spending by households, businesses, and governments) relative to potential output.

What’s at Stake in Harris v. Quinn

The Supreme Court is about to issue a decision on a case that could hit working people—especially working women—right in the paycheck. Harris v. Quinn is about isolating individual workers so they are weak and unable to protect themselves in a labor market that fails to reward their hard work. By weakening the unions that have organized home care workers, given them a voice, and helped them win wage and benefit increases that are lifting many of them out of poverty, Harris v. Quinn could block the road to economic opportunity for a largely female, economically disadvantaged workforce. Right-wing groups want the public to think Harris v. Quinn is as a case about freedom of speech and association; they pretend it is about protection of the individual—but how does it protect an individual if the end result is a smaller paycheck?

American workers, by and large, have suffered from stagnant wages for decades. At the same time, the percent of working Americans in unions or covered by union contracts has been falling. Studies suggest that a substantial part of this wage stagnation is the result of eroded unionization, as fewer workers, both union and nonunion, benefit from the unions’ ability to improve wage standards in particular industries and occupations. The consequence: profits have reached historic highs, CEO pay is in the stratosphere, but workers are not sharing in the nation’s ever-increasing wealth.

Almost anything that worsens these trends ought to be avoided, including anything that weakens unions or makes it harder for workers to bargain successfully. Americans need a raise: more pay for the work they do, better benefits, and more regular hours, and they need help in getting it. On their own, the ability of individual Walmart cashiers, for example, or Amazon’s warehouse workers to get a raise is negligible. But collectively, if they can join together and bargain as a group, they would have a chance to exert enough leverage to make the companies listen to their demands. The players in the NFL, MLB and NBA all know that what they have won had to be wrested from management.

Teachers, “Tenure,” Due Process, and Truly Helping Disadvantaged Children

This month, a California judge struck down California’s teacher tenure law in a landmark case, Vergara v. California. Proponents claim that eliminating tenure will mean fewer ineffective teachers at low-performing schools. But teacher tenure in the K-12 context does not mean a lifetime guarantee of a job. It means that teachers have basic rights—most importantly, the right to due process if the district wants to fire them. This distinction is critical, both because eliminating tenure does not necessarily make it easier to fire bad teachers, and because tenure can actually help attract good teachers to hard-to-staff schools, retain them, and support their role as voices for student justice in those schools.

There have been many good commentaries on why the Vergara ruling will do little to help students. Washington Post columnist Catherine Rampell nails the essential point, writing, “Making it easier to fire bad teachers isn’t going to magically cause the educational achievement gap to disappear. You need to be able to attract and retain more good teachers, too.”

New York University professor (and EPI board member) Pedro Noguera notes in the Wall Street Journal that both the plaintiffs’ suit and the judge’s verdict are fundamentally flawed. Noguera agrees that there are disparities in teacher qualifications and quality between schools serving high- versus low-income students, but tenure does not contribute to these differences. The fact is that schools serving low-income students have less funding and fewer resources than schools in more affluent areas. That means they aren’t able to pay teachers as much. It means class sizes are larger, nurses and counselors are fewer, libraries are worse. These and many other factors make it harder for low-income schools to attract and retain good teachers. The due-process protections afforded by tenure, at the very least, ensure that teachers who do stay in high-poverty schools can speak out against these inequities and be advocates for a more just system for their students.

American Workers Need Overtime Protections

Today, Sen. Tom Harkin (D-IA) and eight co-sponsors introduced legislation to restore overtime protections for low- and mid-wage salaried workers. The Restoring Overtime Pay for Working Americans Act would guarantee overtime pay for millions of salaried workers earning less than $52,000 a year.

Americans are working longer hours and are more productive than ever—yet wages are largely flat or falling. Indeed, the median worker saw a wage increase of just 5.0 percent between 1979 and 2012, despite overall productivity growth of 74.5 percent. One reason Americans’ paychecks are not keeping pace with their productivity is that millions of middle-class and even lower-middle-class workers are working overtime and not getting paid for it. This is because the federal wage and hour law is out of date—and especially the regulation that sets the salary level below which all employees must be paid time-and-a-half for their overtime hours.

Updating overtime rules is one important step in giving Americans the raises they deserve. If the threshold is raised from its current $455 per week ($23,660 annually) to $984 per week ($51,168 per year, the threshold’s 1975 level, adjusted for inflation) millions of salaried workers would be guaranteed the right to overtime pay if they work more than 40 hours in a week.

This bill would go above and beyond the recent announcement by President Obama in strengthening overtime pay regulations. I salute Sen. Harkin for taking up this issue and calling for a reasonable salary level, indexed for inflation, along the lines Jared Bernstein of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and I have advocated. Sen. Harkin led the battle in Congress in 2004 to block a set of very detrimental changes the Bush administration made to the overtime rules. While Sen. Harkin was not entirely successful, he did force the Bush Labor Department to issue a final rule that was less damaging than its first proposal. It’s heartening to see that both Sen. Harkin and his colleagues, along with the Obama administration, continue to believe that low and mid-level workers should be paid when they work overtime. If more workers were paid time-and-a-half when they worked overtime, it would boost the economy and show that in America, hard work pays off.

A Repatriation Holiday to Fund the Highway Trust Fund is Not Only a Bad Idea but a Costly One

In politics, bad ideas never go away, even after being shown to be bad. A repatriation tax holiday is a case in point. Senators of both parties have suggested using revenue generated from a repatriation holiday to plug near-term shortfalls in the Highway Trust Fund, which will be depleted within a couple of months. The problem, of course, is that revenues are only generated in the short-run, and revenue losses in out-years dominate the overall budget impact of a repatriation holiday.

Under its baseline budget, the Congressional Budget Office projects a fiscal year 2015 Highway Trust Fund shortfall of about $12 billion. The Joint Tax Committee projects that a repatriation holiday enacted this year would bring in about $13 billion in additional revenue in fiscal year 2015. Sounds like a great fix for a budget problem. What is not mentioned is cumulative Highway Trust Fund shortfalls between 2016 and 2024 total $824 billion and that the repatriation holiday will reduce federal tax revenues by $115 billion over the same period. Consequently, using a repatriation holiday as a short-term fix would increase longer-term federal budget problems associated with underfunding the Highway Trust Fund—increasing projected deficits from $824 billion to almost $1 trillion over the next 10 years. Surely, a repatriation holiday is a bad and costly idea.

But there are also other problems with a repatriation holiday, which requires a brief and, admittedly, wonkish review of the 2004 repatriation holiday.

Thoughts on the Black Labor Force Participation Rate

Recently, my Economic Snapshot on the resilience of black labor force participation has gotten some attention in a few well-known media outlets. The main finding of the snapshot was that part of the reason the black-white unemployment rate gap has grown during the post-Great Recession period is because labor force participation has fallen by less for blacks than for whites. In a blog post for the Washington Post, Philip Bump examined the robustness of that observation by comparing historic data on labor force participation rates and unemployment rates for blacks and whites dating back to 1973. He concludes that “the problem is that Wilson’s explanation doesn’t appear to hold up over time.”

But this is only a problem if one assumes I was making a statement about the entire run of post-World War II U.S. economic history. I wasn’t. I was instead looking only at why the black-white unemployment gap grew in the past seven years. Importantly, focusing on these particular seven years is not an arbitrary or random selection—that’s the period of time since the previous business cycle peak, a span of time often looked at by researchers to assess labor market trends. That being said, I think Philip’s exercise is an interesting one and worth repeating, by comparing changes over similar periods of time in previous business cycles.

If Obama Must Delay Deportation Review, Relief For Unauthorized Immigrants Should Be Bold and Broad

Over the past five years under President Obama’s leadership, the U.S. immigration enforcement system, including its main tools of migrant detention and deportation, has vastly expanded into a “formidable machinery” that has expelled unauthorized immigrants at a record pace—a total of approximately 2 million in five years. A year ago, the Senate made progress toward fixing the system by passing a bipartisan comprehensive immigration bill that would reform almost every aspect of the immigration system, including legalization and a path to citizenship for unauthorized immigrants. But the effort has stalled in the Republican-controlled House of Representatives…

Looking at Segregation Through the Peer Effects Lens

That our children attend schools that are segregated by race is probably not a surprise for any of us. While, as researchers, we might debate how consequential segregation is, we can likely agree that, on its face, segregation raises some important societal concerns; it challenges our sense of what a moral and fair system looks like. It poses barriers to social cohesion, inclusion, and integration—and their well-known positive impacts on society—and it limits our children’s preparedness for the multicultural world in which they live.

As we mark the 60th anniversary of the Supreme Court’s Brown vs. Board of Education decision, and the declaration that “separate but equal” is unconstitutional, we look back on both progress made in desegregating schools and, more recently, backtracking on those efforts and current initiatives that sideline them. Although separate but equal is unconstitutional, separate and unequal is very much a reality.

Most Missing Workers Are Nowhere Near Retirement Age

In today’s weak labor market, there are around 6.0 million “missing workers”—potential workers who, because of weak job opportunities in the aftermath of the Great Recession, are neither employed nor actively seeking work. Some have suggested that many of these missing workers may be at or near retirement age and, in the face of weak job opportunities, have simply decided to retire earlier than they otherwise would have. While this would clearly indicate a huge waste of human potential and a serious indictment of macroeconomic policymakers that allowed economic weakness to linger on so long, it would also indicate that these workers are very unlikely to rejoin the labor force in coming years no matter how dramatically economic conditions improve. This would in turn mean that their absence is not in fact an indicator of current slack in the labor market.

The figure below provides an age breakdown of the missing workforce. It shows that nearly three-quarters of missing workers are age 54 or younger, which means they are unlikely to be early retirees. Even if all of the missing workers age 55 and over will never reenter the labor force no matter how strong job opportunities get, that still leaves 4.4 million missing workers age 54 or younger who would be likely to re-enter the labor force when job opportunities strengthen. In other words, weak labor force participation rate remains a key component of total slack in the labor market.

Women Surpassed Their Pre-recession Employment Peak 9 Months Ago, Men Still Haven’t

With the addition of 217,000 jobs in May, the U.S. labor market has now surpassed its pre-recession employment peak, a benchmark (the pre-recession employment peak) which is of zero economic interest. Given the growth in the potential labor force since December 2007, we should have added 7.0 million jobs since then, but instead we have added a net 113,000, so the labor market is still 6.9 million in the hole.

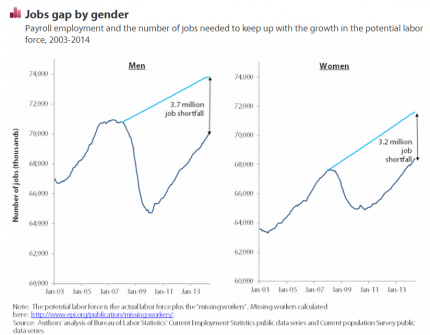

One interesting piece is the breakdown of that jobs gap by gender. As you can see in the chart below, women actually surpassed their pre-recession peak last August, but are still 3.2 million jobs in the hole given growth in the potential female labor force since December 2007. Men, on the other hand, are still nearly 700,000 jobs below their pre-recession employment peak, and given growth in the potential male labor force, are 3.7 million jobs down.

Statistics that Spin: Foreign Goods to Be Considered U.S. Goods?

This past year, President Obama’s commitment to rebuilding our nation’s manufacturing sector has taken center stage. In February, he explained why producing goods here at home is important to our country:

“For generations of Americans, manufacturing was the ticket to a good middle-class life. We made stuff. And the stuff we made—like steel and cars and planes—made us the economic leader of the world. And the work was hard, but the jobs were good. And if you got on an assembly plant in Detroit or in a steel plant in Youngstown, you could buy a home. You could raise kids. You could send them to college. You could retire with some security. And those jobs didn’t just tell us how much we were worth, they told us how we were contributing to the society and how we were helping to build America, and gave people a sense of dignity and purpose. They saw a Boeing plane or one of the Big Three cars rolling off the assembly line, and they said, you know what, I made that. And they were iconic. And people understood that’s what it meant for something to be made in America.”

The president has continually called for curtailing corporate incentives to outsource manufacturing to other countries, saying “it is time to stop rewarding businesses that ship jobs overseas, and start rewarding companies that create jobs right here in America.” A White House fact sheet summarizes his plans for restoring U.S. manufacturing jobs.

Apparently, some folks in the administration haven’t gotten the message. On May 22, the Office of Management and Budget issued a notice for comments on a proposal to dramatically alter the way government keeps statistics on domestic industries. The proposal suggests “that factoryless goods producers (FGPs) be classified” as manufacturers.

What to Watch on Jobs Day: An All-time High of an Indicator That is Almost Always Rising

It is very likely that when the jobs numbers are released tomorrow morning, we will learn that the total number of jobs in the U.S. labor market surpassed its pre-recession peak. I predict you will see many headlines along the lines of “U.S. Employment at All-Time High.”

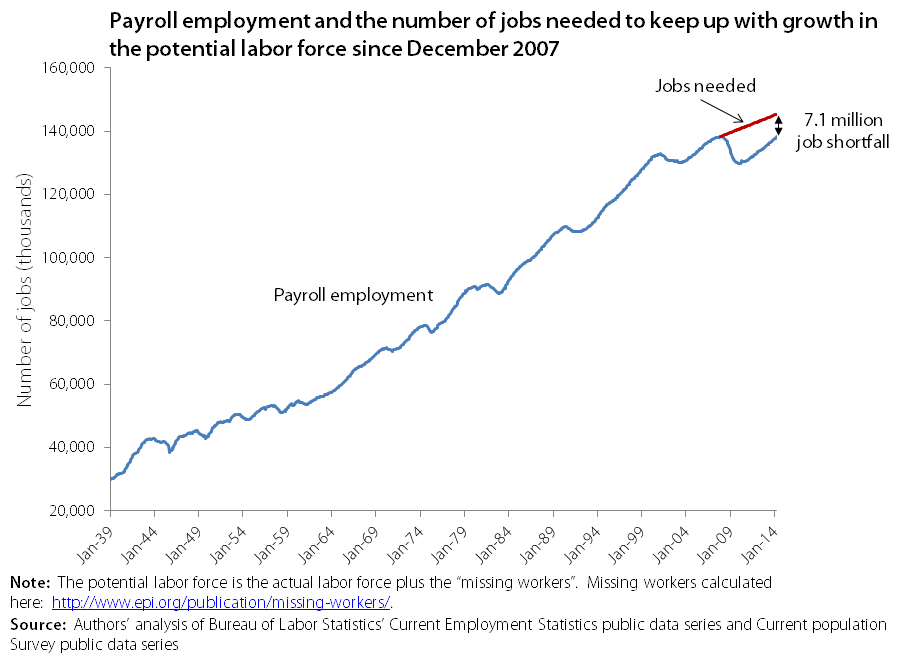

It is difficult to exaggerate how not a big deal this is. Total employment is almost always rising, as the figure below shows. An all-time high of something that is almost always rising is just not that interesting.

Furthermore, it is an utterly meaningless benchmark economically. Because the working-age population (and with it, the potential labor force) is growing all the time, we should have added millions of jobs over the last six-plus years just to hold steady. That means that when we get back to the prerecession employment level, there will still be a huge gap in the labor market. We currently have a gap in the labor market of 7.1 million jobs. When the numbers are released on Friday, that gap will likely drop to 7.0 million. We are far, far from healthy labor market conditions.

How Much Should You Be Making?

In honor of EPI’s new initiative, Raising America’s Pay, we updated our wage calculator, which shows how much you would be making if wages had kept pace with productivity. Having wages for the vast majority of American workers keep pace with productivity is a key indicator of an economy that is working for all.

Economic inequality is a real and growing problem in America, but the discussion around addressing inequality too frequently sidesteps a crucial component: the key to shared prosperity is to foster wage growth for the vast majority of Americans who rely on their paychecks to make ends meet. In fact, raising the pay for most Americans is the central economic challenge of our time—essential to ameliorating income inequality, boosting living standards for the broad middle-class, reducing poverty, and sustaining economic growth.

Crucially, the large and growing wedge between productivity and typical workers’ pay is not inevitable. For example, in the three decades following World War II, wages did rise with productivity and living standards improved throughout the income distribution. Since then, however, the rewards to a growing economy over the last three-and-a-half decades have primarily accrued to those at the top (except for the period of tight labor markets in the late 1990s). Since 1979, the workforce is more educated, is working more, and produces more goods and services in every hour worked. And yet the vast majority of workers are not reaping the rewards of their increased productivity.

Identifying the Channels Through which Regulatory Changes Affect Jobs

The Environmental Protection Agency is scheduled to release new regulations restricting the emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs) from existing electrical generating units (EGUs, or power plants) next week. These new regulations will almost surely inspire a lot of debate over their effect on economic growth, and particularly on employment.

It is important to note first that the overall desirability of these proposed changes is dominated by their impact in forestalling global climate change. In strict economic terms, this consideration dwarfs any plausible estimate of the rule’s impact on jobs. Yet joblessness and weak labor markets continue to loom large as chief concerns of Americans (as well they should), and debate on these grounds will surely continue. Given this, even though the employment impacts of the rule are small relative to the environmental impacts, they still should be examined correctly.

Employment channels: Net versus gross and short versus long-runs

This blog post details the various channels through which environmental regulations have the potential to affect employment levels in the U.S. economy. To begin with, the effect of regulations on the net level of overall employment in the U.S. economy is the result of the sum of larger gross employment gains and losses across industrial sectors. So, for example, even if analysis finds that the new regulations will result in small net employment gains nationwide, this does not mean that no jobs in the U.S. economy will be lost due to the rules. Instead, it simply means that the total sum of employment gains and losses across all sectors is positive.

Not a Chimera: Global Economic Trends Tend to Have Global Economic Causes

The Brookings Institution’s Mark Muro and Scott Andes recently published two blog posts which claim that the problems of U.S. manufacturing demand being depressed by large trade deficits—particularly trade deficits with China—are “a manufactured chimera,” and that the problems facing U.S. manufacturing are actually just evidence of insufficient domestic innovation. By deflecting attention from China’s manufacturing surplus, and the trade and currency policies China has used to dominate the market for manufacturing exports, Muro and Andes are distracting, not educating, those genuinely concerned with giving U.S. manufacturing a chance to compete in global markets. Claiming that it’s the domestic pace of innovation that is somehow the real cause of trouble is oddly provincial, and ignores some key global facts—like the fact that China has doubled down on its currency manipulation policies in the past year, and that its manufacturing trade surplus is projected to grow in the future unless something is done about it.

The most fundamental problem facing U.S. manufacturing is a shortage of demand for U.S. manufactured products. Four years after the end of the Great Recession, real U.S. manufacturing output was 2.2 percent below its pre-recession level. Demand for U.S. manufactured products was much higher at this point in earlier business cycles: 11.1% higher in 2005 (after the end of the dot-com bubble), and 23.9 percent higher in 1995, four years after the 1990-1991 recession. In other words, our manufacturing problem today is, first and foremost, a macroeconomic problem. Without adequate demand, manufacturers will not invest in R&D, build new plants, or hire new workers. Demand for output from U.S. manufacturing can either come from domestic sources—American consumers, businesses and governments—or from foreign sources. Net foreign demand for U.S. manufacturing output is best measured simply as net exports (exports minus imports) of manufactured goods.

The Federal Reserve, Full Employment, and Financial Stability

The Federal Reserve, even after recent announced nominees take their jobs, will have two vacant slots on the seven-member Board of Governors. For a number of reasons, it even more vital than ever that these next two nominees be committed to using all the tools at their disposal (including the new ones provided by Dodd-Frank) to (1) generate genuine full employment in the American labor market and (2) rein in financial sector excesses that threaten economic growth and stability.

Targeting full-employment

Since roughly the end of 2008, a large majority of monetary policy observers have agreed that the Fed should focus entirely on boosting economic activity and employment, and not worry at all about inflationary pressures.

This is not the normal state of the world. Normally, it’s thought that the Fed must walk a narrow path between providing support to economic activity and employment, but not generating such an excess of aggregate demand that the economy overheats and unleashes inflation. But the extreme economic weakness of the Great Recession crushed inflationary pressures and led to a cratering of economic activity and employment. Hence, it was correctly recognized that this delicate balancing act wasn’t necessary and that attention should instead be laser-focused simply on jumpstarting economic growth.

Now, this large majority for aggressive action in boosting growth and employment looks to be fracturing, and worries about inflation and recommendations that the Fed stop its single-minded focus on generating a full recovery are surfacing.

These are odd arguments to be making with the unemployment rate still matching the highest peak it ever reached in the 2001-03 recession and ensuing jobless recovery, especially considering that the headline unemployment rate has been driven down largely by the 6 million potential workers who are not actively searching for work but who would very likely join the labor force should job opportunities become less scarce. In essence, the arguments for a Fed “exit” from extraordinary efforts to boost recovery hinge on claims that very low rates of employment and very high rates of unused productive capacity relative to historic norms are not actually signs that the economy is operating below potential, because the resources idled by the Great Recession cannot be re-mobilized and should be just be considered gone forever from productive life. Importantly, however, this pessimistic argument has not been bolstered by any evidence showing that wages and prices are rising atypically fast. Indeed, the key measure of inflation tracked by the Fed has actually been pretty steadily decelerating in recent years—which is normally a sure sign that there is indeed lots of productive slack in the economy.

Don’t Pull the Rug Out from Under PSLF Recipients

Earlier this month, EPI released its annual “Class of 2014” paper, which examines labor market trends for recent high school and college graduates. Among other trends, authors Heidi Shierholz, Alyssa Davis and Will Kimball highlight the problems recent graduates face when they graduate with high levels of student debt. Student debt continues to be one of the biggest reasons young people postpone major purchases like cars and houses, and repayment can be difficult if students can’t secure their first job after graduation. Congress’s past failures to keep interest rates on student debt low, let alone provide a comprehensive refinancing plan (although that could change with Senator Warren’s new bill), should be cause for concern for recent college graduates.

President Obama’s 2015 budget proposal, released in March, makes college affordability a priority by broadening the scope of the Pay as You Earn (PAYE) repayment program to all student borrowers. Currently, for qualifying students, PAYE allows high-debt, low-income students to pay a lower monthly payment (10 percent of their income) than the standard 10-year repayment plan requires, and provides total loan forgiveness to graduates after 20 years of qualifying repayments. The administration proposed expanding the program to all students beginning July 2015 and making it the only income based repayment option, providing access to affordable repayment options for all student s and simplifying the repayment experience.

While additional reforms proposed to PAYE (page 13 here) seem common sense (eliminating caps for high-income borrowers and calculating payments for married couples using combined household adjusted gross income instead of calculating payments separately), part of the budgetary cost of this expansion is recouped by capping loan forgiveness on a subset of the PAYE repayment program, graduates enrolled in the Federal Public Service Loan Forgiveness program (PSLF).

Stronger Overtime Rules and Job Creation

If I told you that the legislature of State X is going to make it easier for workers in the state, including public employees, to earn overtime pay, you might wonder what effect that would have on employment in the state. What if the cost to employers from having to pay more workers time and a half for overtime is so high that it causes businesses to move to a neighboring state that has a weaker requirement? Or what if it raises costs and employers respond by laying off employees?

Those fears are being raised by groups like the National Retail Federation, the Heritage Foundation, and the CATO Institute, all of which oppose President Obama’s plan to revise the Fair Labor Standards Act regulations that govern the right to overtime pay. The president wants to make it easier for relatively low-paid employees to earn overtime pay when they work more than forty hours in a week, but the conservative business lobbyists are already yelling about job loss—with no real explanation or evidence that job loss is a realistic outcome.

Fortunately, California provides a kind of natural experiment about what happens when more workers have a right to overtime pay, and the results are reassuring. Regardless of their job duties, California law guarantees overtime pay to employees earning less than $640 per week, while its neighboring states—Arizona, Nevada, and Oregon—only guarantee overtime pay to workers paid less than $455 per week, less than a poverty level wage for a family of four. Other rules in California make it harder for employers to deny overtime pay to even better paid workers whose jobs include duties that could be considered managerial or professional. In California, but not in its neighboring states, an employee has to spend a majority of his time doing managerial or professional work in order to be excluded from the right to receive overtime pay.

Maybe China’s Currency Isn’t Undervalued—Really?

In a blog post, Martin Kessler and Arvind Subramanian of the Peterson Institute claim that, contrary to popular belief, the Chinese renminbi is not undervalued. Their assertion is based on new estimates of prices and income in China relative those in the United States. The Wall Street Journal concludes that the world should “stop bugging China on the undervaluation of its currency.”

However, by failing to consider the effects of China’s purchases of foreign exchange reserves and its significant trade surplus, the Kessler-Subramanian model appears fatally flawed. China invested more than half a trillion dollars in purchasing foreign exchange reserves in 2013 alone—a new record. But for those purchases, the value of the RMB would have been significantly higher. Kessler and Subramanian claim that the RMB was “only slightly undervalued in 2011” is simply not credible, when that exchange rate is being sustained with such massive purchases of foreign exchange reserves.

In fact, China’s currency needs to rise in value every year because productivity growth in manufacturing is so much higher than in the United States and other countries. Between 1995 and 2009, China experienced manufacturing productivity growth that ranged between 6.7 percent and 9.6 percent per year. Over the same period, productivity growth in U.S. manufacturing averaged only 2.4 percent per year. Thus, China must allow its currency to rise by four to seven percent a year simply to keep its trade surplus from expanding.

Wage Stagnation among College Graduates and Senator Warren’s Plan to Help

Earlier this month, we released our “Class of 2014” report on the labor market and earnings prospects for the high school and college graduates of 2014. In short, things don’t look great. The prolonged slack in labor demand—unemployment for college graduates is 8.5 percent compared to their 2007 levels of 5.5 percent—has depressed earnings for the majority of recent graduates. To make matters worse, student loan debt reached an all-time high of about $1.2 trillion. Coupled with young college graduates’ stagnant wages, student debt poses an obstacle to graduates seeking financial security.

The figure below shows the real average hourly wages of young college graduates (ages 21-24) by gender. Inflation-adjusted hourly wages fell by 6.9 percent for college graduates since 2007, which means full-time, year-round workers are earning $2,600 less in total annual wages. What’s more, the downturn has only exacerbated the wage stagnation young college graduates were already experiencing. Wages for all college graduates fell 0.9 percent between 2000 and 2007, from $18.41 in 2000 to $18.24 in 2007. Female college graduates saw their wages decline by 4.6 percent over that time period ($17.82 to $17.00). Male college graduates did experience a 3.7 percent increase in hourly wages from 2000 to 2007, but those mild gains were quickly erased by the Great Recession. College graduates simply did not see any signs of consistent wage growth prior to the Great Recession. Clearly, it is not necessarily the case that as long as you obtain a college degree, you’ll be gainfully employed and well compensated.

The class of 2014—most of whom started college after the Great Recession was officially over—likely figured that by the time they graduated the labor market would have recovered to the point that their job prospects and future earnings would make their student debt manageable. Sadly, this has not been the case, and the effects will likely be long lasting.

How the Great Society Democratized Our Economy

The media buzz surrounding the 50th anniversary of Lyndon Johnson’s May 1964 speech announcing his Great Society has focused on the question, did it “work?” In other words, did the 200-odd pieces of legislation passed over the following two years succeed in their goals of reducing poverty, improving education, providing health care for the elderly, etc. Judgments as to how the programs worked are supposed to answer the bigger question, should government intervene in the economy to make life better for its people?

It is a safe bet that the components of the Great Society—especially those dealing with the War on Poverty—are the most studied in the history of social science. For half a century, a vast army of economists, sociologists, political scientists, lawyers, and policy analysts have poured over the data. There is little doubt that almost all of the programs had benefits. The debate between conservatives and liberals is whether the benefits were worth the “costs.” But if by this time the research has not reached convincing definitive conclusions, it is unlikely that it ever will.

Part of the problem is that such efforts to quantify cost and benefits, while useful, are inherently flawed by their reliance on market prices to establish the human value of, for example, living longer, educating a poor child, or breathing cleaner air.

They also miss the point. The Great Society was much more than the sum of its parts. Like the New Deal before it, the Great Society changed the way Americans thought about the relationship of the government to the economy.

Beyond Pre-kindergarten: Evidence and State-Level Action

A new policy guide from the Broader, Bolder Approach to Education (BBA) and the Schott Foundation’s Opportunity to Learn Campaign shows how to build high-quality early support systems for children that strengthen communities and families, promote and sustain early education, and enable children to thrive. It also covers ways to resolve one of our nation’s most intractable problems: the academic achievement gap.

We know that children arrive at kindergarten with already large gaps that divide them along lines of race, ethnicity, and social class. We know, too, that these gaps prove stubbornly difficult to close, and that they are very often widened by disparities in access to appropriately credentialed teachers, small classes, school resources, health care, nutritious meals, and other related factors.

The Economic Policy Institute, where BBA is housed, has been a leader not only in documenting these gaps, but in producing research showing how to narrow them before they get so hard to tackle. For example, in 2007, EPI calculated the economic and social benefits of investing in a voluntary, high-quality publicly funded prekindergarten program that would narrow gaps by helping disadvantaged students achieve their full potential. Seven years later, this is a cornerstone of President Obama’s proposal for early childhood investments, and of the Strong Start for America’s Children Act bills proposed by leaders in both houses of Congress.

Harris v. Quinn Is About the Right of Home Care Workers to Improve Their Wages

The Supreme Court is expected to decide Harris v. Quinn, a case of major importance for American workers, in the next few days. Many observers predict a disastrous decision that will cripple union organizing and collective bargaining for home health aides, child care workers, and other direct care aides. But the Court could go much further and threaten the ability of all public employees to form unions and bargain collectively with any state or local government.

The case involves the ability of public employees to bargain for a provision in their contracts (known as an agency fee) requiring every covered worker to pay his or her fair share of the cost of maintaining the union, negotiating a contract, and enforcing its provisions. A majority of states allow such provisions, but so-called right-to-work states do not.

Why is this so important? Wages in most occupations have stagnated or fallen since 2000, even as profits have climbed to historic heights and inequality has worsened. The erosion of the minimum wage, rising CEO pay, and many other factors have played a role, but the decline of unions is near the top in importance. Business and conservative groups have lobbied around the nation to impose right-to-work as a way to weaken unions and keep wages low. It’s a successful strategy: research shows that workers in right-to-work states are paid $1,500 a year less, on average, than employees where unions are free to bargain for agency fees. Negotiating and administering union contracts, organizing employees, and winning elections is expensive, especially when outside groups and politicians mount well-funded opposition campaigns, as recently occurred at Volkswagen in Chattanooga, TN. Right-to-work laws allow employees to get the benefits of union contracts without paying their fair share, drying up a key source of the funds unions need to survive.

In Remembrance of Harry Clay Ballantyne

I was saddened to learn that Harry Clay Ballantyne, who led the Office of the Actuary at the Social Security Administration, recently passed away. Harry was an exemplary civil servant and private citizen. Long after his retirement, he co-authored an EPI report dispelling the myth that Social Security, which must operate in long-term balance, was driving our nation into debt. Although he was in weakening health, he was determined to defend the program he had devoted his career to. And though he was not the type to flaunt his achievements, an important part of the story was that Social Security’s actuaries, far from being taken by surprise by the Baby Boomer retirement, increases in life expectancy, and other supposedly calamitous demographic trends that critics liked to suggest had crashed the system, had accurately predicted them years ago and dealt with them. What no one inside or outside Social Security had predicted was that wage stagnation, rising inequality, and the Great Recession would erode the program’s funding—problems that suggest entirely different solutions.

More Than Half a Million Jobs Are at Risk Due to Unfair Trade in the U.S. Steel Industry

Earlier this week, I estimated that up to half million (583,600) U.S. jobs are at risk due to surging imports of unfairly traded steel. A recent post by blogger Tim Worstall suggests that the number can’t possibly be that large because the steel industry employs only 150,000 people. But this misses the point—the risk to the steel industry goes far beyond the steel companies themselves, and the workers they employ. It also includes workers in iron ore and coal mines, in other manufacturing industries that support steel production, as well as lawyers, accountants, managers and other workers who supply services to the steel industry. All these jobs, 583,600 in total, are threatened by the flood of steel imports.

Half of the 46 top steel companies in the world were government-owned, and they accounted for 38 percent of global production. Illegally dumped and subsidized steel products are stealing market share and jobs from domestic producers. Worstall claims that we should ignore unfair import competition because, “if we get cheaper steel then this makes us all richer.” He concludes that “the market price is the fair price” for imports.

Responding to a similar question from a reporter this week, Ohio Senator Sherrod Brown said that this is “like arguing it’s OK to buy stolen TVs because they are cheaper.” Even a market economy needs rules to prevent cheating and unfair trade.

Worstall claims that we performed “some very heroic calculations” in estimating the jobs at risk due to unfair imports. He goes on to claim that “what is being done here is to assume that… steel workers buy restaurant meals so waiters are employed…and so on.” But this is exactly what we did not do.

Our model used standard data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics to estimate the direct and indirect jobs supported by U.S. steel production. Indirect jobs include those in production of “input commodities such as minerals and ore, coke, and other fuels, as well as downstream services and other resources consumed in the production of and distribution of steel products.” Furthermore, we very clearly stated that our estimate did “not include respending jobs supported by the wages of workers in the steel industry.”

The Deep Roots of Skilled Labor Shortages: Anti-Union, Anti-Worker Corporations

A recent story from NPR’s Andrew Schneider, about a construction boom and skilled labor shortage in Texas, is missing some of the links needed to understand what is happening there and why. The elements are all there: the huge loss of construction jobs following the financial crisis in 2008, the energy boom creating jobs regionally even while construction employment nationally remains about a million and a half jobs lower than its peak, a decline in unauthorized immigration, and contractors grudgingly increasing pay to attract workers.

The two missing links are the role of the construction owner, like Chevron, in crushing the unions that provide skilled journeymen in the construction trades, and a clear discussion of the wage levels needed to attract skilled workers from parts of the country the recovery hasn’t reached. The story says wages are rising in Texas, but from what to what? Are wage levels high enough to persuade a journeyman electrician from Michigan or Los Angeles to relocate to Houston? Or are they unreasonably low, given the scarcity of skilled workers and the years of training required to produce a journeyman? How do union wages compare with non-union wages? The story never says.

Oil giants like Chevron can afford to have their construction contractors pay well for skilled work, but they resist. Organizations they fund, such as the Business Roundtable, have led a decades-long campaign to weaken or destroy the building trades unions that actually train the greatest number of skilled tradesmen. Chevron, Koch Industries, ExxonMobil and many other energy industry corporations fund the American Legislative Exchange Council and its legislative efforts to kill unions and eliminate labor standards. It’s hard to hear Chevron complain about a labor shortage when Chevron and other Fortune 500 companies themselves are a major cause. They don’t merely fight unionization, they also oppose the state and federal prevailing wage laws that protect construction wages from being driven lower and allow union apprenticeship programs to continue providing the best-trained workers.

Schneider is wrong to suggest that community college vocational training programs are the long-term solution to the shortage of skilled labor in Texas. The real solution is to restore the power and reach of the unions, raise wages to attract more workers, and grow the only proven way to develop the necessary skilled labor—apprenticeship programs funded by employers and jointly administered by unions and employers.

Wages of Young Female College Grads Are Lower Today Than They Were In 1989

One of the most shocking findings from Heidi Shierholz’s, Will Kimball’s, and my research on young graduates is that inflation-adjusted wages for young female college graduates are lower today than they were in 1989. Average real wages for young female college graduates are currently $15.29, whereas 25 years ago they were $16.12 (in 2013 dollars)—a decrease of 5.2%.

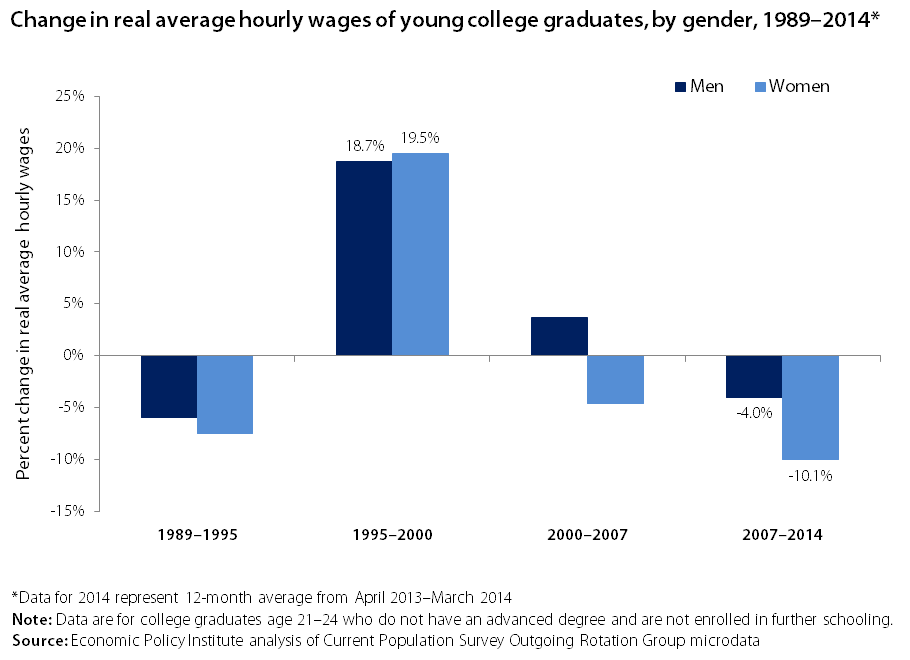

This is part of a wider trend of wage stagnation and decline since 1989 for both men and women. For all college graduates ages 21-24 (male and female combined), wages today are only 2.4% higher than they were in 1989. This growth was driven entirely by the prosperous economy of the late 1990s, when young grads of both genders saw wage increases of close to 20%. Outside of that time period, however, wages have stagnated or declined, with women seeing especially large declines in the 2000s.

The figure below illustrates how the weak economy since 2000 has disproportionately hurt young women college grads’ wages as compared to men’s. Although women saw wage gains in the 1995-2000 period of strong economic growth, women’s wages have declined by 14.2% since 2000, with most of that loss in the period since the start of the Great Recession in 2007. In fact, since 2007, young women college grads have seen their wages fall 10.1%, while men’s wages declined 4%.

Our research showed that young college graduates’ fates are closely tied to the fate of the overall economy. The current weak labor market not only makes it difficult to find a job, but it also means that there is no need for employers to increase wages, as it is easy to keep the workers they need at lower wages when workers have no other options. If we want to reverse the wage losses that occurred due the Great Recession, we need to invest in our economy in ways that will boost aggregate demand and spur job growth, which will in turn improve wage growth for workers with jobs.

California School Board Rejects Rocketship Charter School

Last Thursday, the Alum Rock school district, part of metropolitan San Jose, California, voted to reject a charter school application from the Rocketship chain of schools. As I detailed in a recent paper, Rocketship’s model, which relies on cheaper, inexperienced teachers and completely replacing teachers with computer applications for a significant part of the day, is being promoted for poor urban children, but is dismissed as inadequate by more privileged families.

Rocketship is based in the San Jose area, and thus the Alum Rock rejection represents a rebuff in the part of the country with the most first-hand experience of their methods.

The vote at Alum Rock followed a report by school district staff that identified many of the same problems described in our report. Specifically:

- While Rocketship proposed to serve students from schools that had failed to make Adequate Yearly Progress under the federal No Child Left Behind Law, its application failed to mention that nearly all of Rocketship’s San Jose schools have themselves failed to make Adequate Yearly Progress for at least two years in a row.

- Rocketship’s statement to investors proclaimed that “no assurance is given” that Rocketship schools will make Adequate Yearly Progress in future years.

- Because Rocketship students spend a large portion of their day in computer labs with no licensed teacher, 4th and 5th graders will not receive the minimum instructional hours required by law.

- Rocketship was “misleading” in not including Learning Lab students in its calculation of student-teacher ratio. When all students are counted, “the true student/teacher ratio is, in fact, 37 students to 1 teacher.”